在场所中迷失:雅蒙德/维斯奈斯建筑事务所

马里·瓦顿/Mari Hvat tum

孙萌 译/Translated by SUN Meng

雅蒙德/维斯奈斯建筑事务所(JVA)十分珍视阻力。最令他们头痛的情形莫过于遇到一个没有限制的任务;无限的预算,温带气候中的完美场地,以及由建筑师自己决定功能。与其寻找建筑形式和其众多影响因素之间的互动,他们则更倾向于寻找那些在场地、条件、经济或功能方面有困难的项目,甚至与建筑需求相矛盾。“我们很喜欢‘阻力’或‘摩擦’这些词”, 埃纳尔·雅蒙德说。“……在每个任务中,我们都用我们独特的方式寻找非常规的情况、有意思的场地和约束条件……它们在后来的设计中将成为创造性的出发点”[1]。这种方式把它们的设计与其他北欧建筑区别开来。事实上,在北欧 “诗意化现代主义”有时显得压抑的环境中,JVA的作品展示了令人耳目一新的非诗意化特质。他们的建筑是颠覆的,既不是遵循特定的“北方”审美,也不是预先设定场所精神。与其说适应环境,不如说JVA的建筑设计发明和再造了居住环境。“我们一直致力于探索自然和结构之间冲突的可能性”,建筑师在“迷失在自然”展览的目录中这样写道。

JVA事务所成立于1996年,由3个合伙人和约15位建筑师组成,该事务所已在国际建筑界占有一席之地。他们的作品在全世界范围内发表和展览,并不断地吸引国外项目,比如“生活建筑”著名的英国夏季住宅系列。其中,JVA的作品与其他著名事务所作品并排建造,如,彼得·卒姆托和MVRDV。从2007年以来,JVA的12个主要建筑作品巡回展穿梭于欧洲和北美之间,也刊登在很多书籍和杂志等出版物上。如果试图把JVA的作品对号入座,结果则会非常多元化。他们的作品和工作方式渗透着很多“学派”的痕迹,从荷兰的实用主义到瑞士的环境主义,从时尚的西班牙抽象主义到1990年代美国西海岸的离奇而赋于表现力的几何主义。在挪威,这种实践通常被视为“可怕的”,拒绝屈从教条主义对于建筑构造纯度的坚持,而这一点正是战后北欧现代主义的特质。JVA自己则热衷于建筑本身,而没有把精力投身于将他们的实践定义或列入任何一个主义或学派。相反,他们培养的快乐和非教条机会主义有令人耳目一新的启发性。

抵抗自然

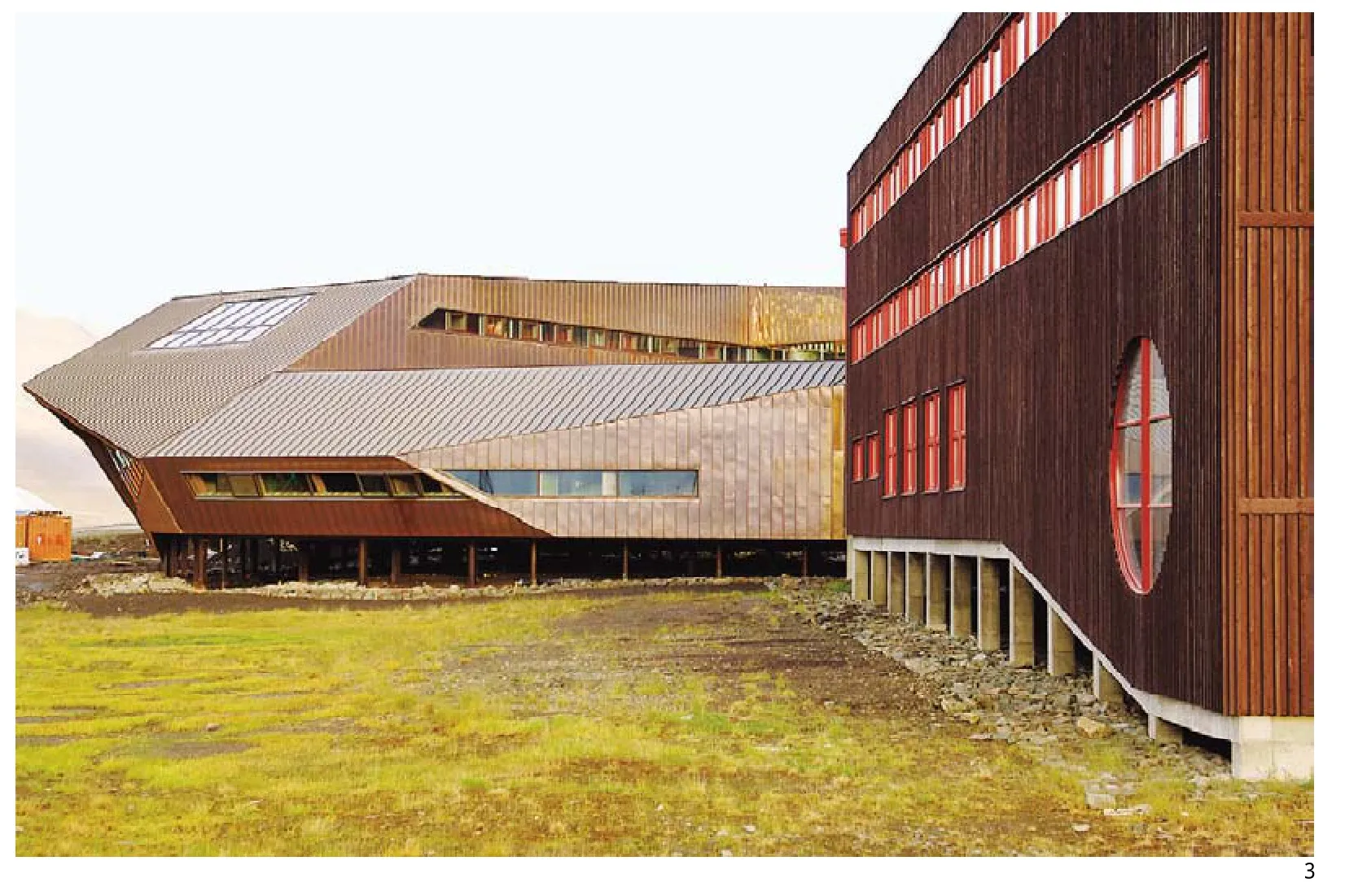

一种独特品质通常会诱发新的东西,北欧建筑所表现的特点包括建造的清晰度、诚实地使用材料和避免人工痕迹。自斯堪的纳维亚设计开始流行以来,金色木墙、天然石材以及有些刻板的清晰构造一直都是北欧现代主义的标志。雅蒙德/维斯奈斯建筑事务所也没有逃出这个持续的神话。比如,斯瓦尔巴特科学中心项目就是对北方地区场所精神的一次实现——是对遥远荒凉的北方地区的原始而自然的回应。实际上,没有任何东西能远离事实。可以肯定的是,JVA的建筑是从自然中得到灵感而构想出来的。他们的很多作品都位于特殊的自然地段之中——从斯瓦尔巴特的干旱北极圈景观,到红房子所在的郁郁葱葱的河谷。但是,JVA的建筑中没有任何东西是“自然的”,包括那些精确的几何形式,仔细推敲过的材料和颜色,或非常优雅的总平面、剖面和立面。比如,斯瓦尔巴特科学中心扭曲的敷铜箔体量,包括它的狭缝状窗户、发光体和斜几何形,都是设计过程的产物,这个过程把形式和功能、场地和气候结合成丰富而没有冲突的关系,这个过程是对自然的挑衅和容忍,而并非模仿它。建筑师形容在努尔马卡(Nordmarka,位于奥斯陆北部的森林区)的小屋时说:“位于一个干净而幽深的森林中,这个小屋和当地环境联系并不多,反而与柔软的山丘及南方地平线方向的湖泊形成更多关联”[2]。对当地环境的痛斥和为其建筑拓宽视野应该被视为纲领性的声明。JVA培育了一个精致和多层次的人造物,其意义在于与自然的对立而非统一或模仿。“我们上一代建筑师在处理自然的方式上有完全不同的信仰”,亚历山德拉·科斯贝格(Alessandra Kosberg)说道,“我们并不把自然作为信仰,而是作为可以被积极利用的东西。”

重新定义场所

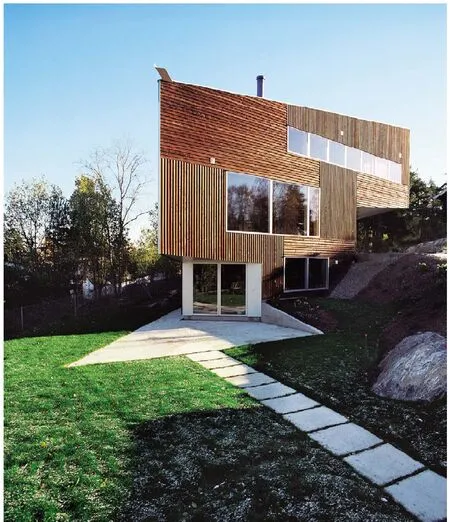

如果“自然”和“自然的”一直是现代挪威建筑界痴迷的主题,和它媲美的只有一个更相关的概念“场所”。历史学家和理论家克里斯蒂安·诺伯格-舒尔茨(Christian Norberg-Schulz)对建筑的思考围绕着场所精神(genius loci) ——当地的精神—— 一个从他对自然景观的本质解释中衍生出的概念[3]。诺伯格-舒尔茨的地形决定论认为,建筑是对景观的模仿式重新定制,该理论对挪威建筑界有很大影响,从斯韦勒·费恩(Sver re Fehn)到文撤·塞尔默(Wenche Selmer)到当代实践中的创新语境主义,比如卡尔·维戈·贺美巴克(Car l-Viggo H¿lmebakk)或克努特·赫特内斯(Knut Hjel tnes)。雅蒙德/维斯奈斯建筑事务所位于整个图景中的什么位置呢?至少是不完美的。“我们不是培育一种方式,而是开发对待自然和场所的一系列策略。这些策略有些可能带有‘诗意’ ——而有些则肯定没有。我们更关心对某个独特条件的特别处理手法,而不是创造某种特定的建筑方式”,雅蒙德说。他们的住宅作品,比如,边缘住宅、白房子和三角形住宅,展示了这种语境机会主义。这3座住宅都建于不同的场地,或者是地形十分陡峭(比如边缘住宅),或者由于场地被挤在高密度郊区环境中,要应对有限的视野和严格的建筑法规(比如白房子和三角形住宅)。这些限制条件并没有成为设计的阻碍,反而激发了赋有创意的解决方案。边缘住宅位于陡峭的场地,使我们提出了独特的悬臂施工方法,即用细长的钢柱悬挑支撑在风景之上。白色住宅位于高密度的郊区环境,使住宅扭曲和旋转,建筑像望远镜一样准确地朝向设计的视角。在三角形住宅中,对高度和面积的严格限制产生了非常规的体量,并对光和空间进行创造性调整。它们都是精巧的小建筑。他们的尺度和材料都没有超出常规,但是它们的几何精度,那些精心设计的开口和严格的材料控制,赋予它们强烈的雕塑感。蒂尔塔格勒酒店(Tur tagr¿Hotel)、努尔马卡小屋及其他很多项目,JVA的设计把建筑本身植入景观并赋予一种奇异的轻盈感,而不是夸张的“语境”姿态。这些作品完全没有模仿既定的场所精神,而是将多种语境编织成全新的质感。

1 斯瓦尔巴特群岛科学中心,夜景/Svalbard Science Cent re, night view

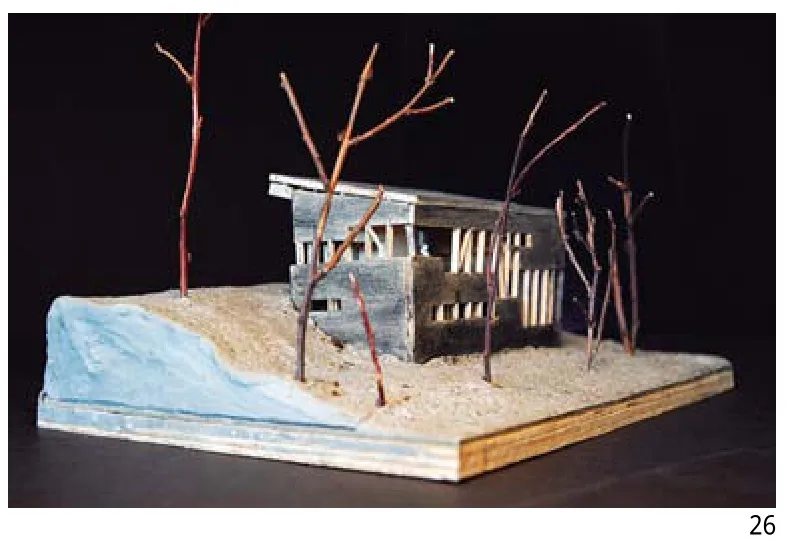

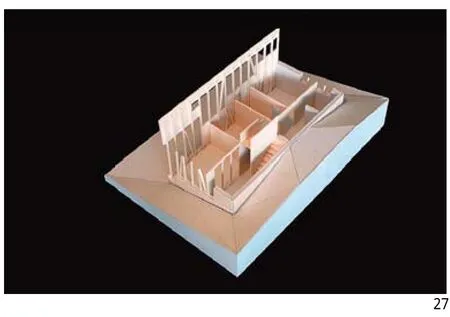

2 斯瓦尔巴特群岛科学中心,模型/Svalbard Science Cent re, model

3 斯瓦尔巴特群岛科学中心,外景/Svalbard Science Cent re, exterior view 1-3 摄影/Photography: Nils Pet ter Dale

4 红房子,外景/Red House, exterior view

5.6 红房子,模型/Red House, model

4-6 摄影/Photography: Nils Pet ter Dale

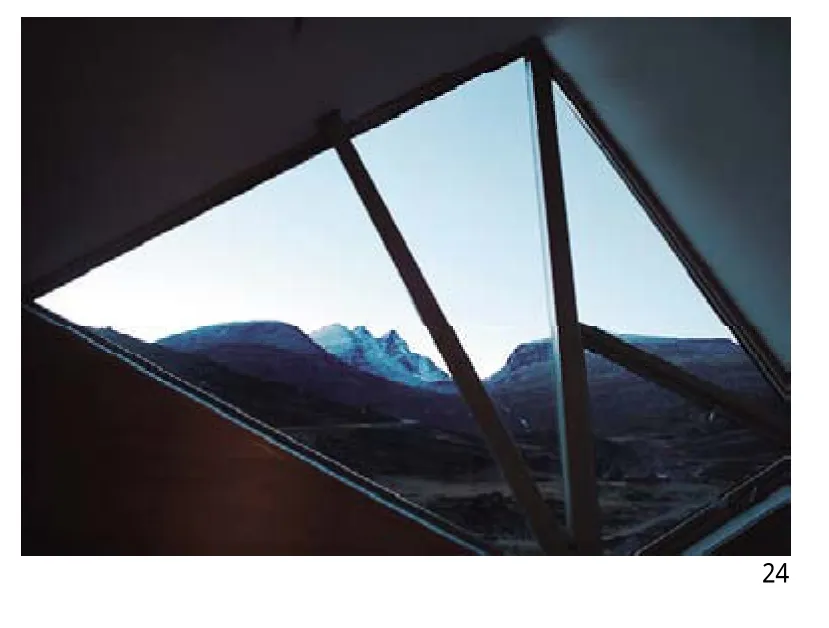

JVA的奇异语境主义的一个很好的例子就是最近刚建成的沙丘住宅,位于英国的萨福克(Suf folk)。 这是由“生活建筑”慈善项目开发的遍布英国的系列夏季住宅之一,它位于风景如画的索普尼斯(Thorpeness)沿海村庄。JVA基于他们自己在英国破旧而古雅的小旅馆的假期回忆,展示了对英国乡村住宅一种奇特的诠释。把半个老虎窗轮廓分解成奇怪而尖锐的构成,他们游走在可识别形式和超现实转换之间。但是,如果这个住宅把场所的某些方面进行转化,它则直接和其他方面连接,比如,玻璃基座直接朝着萨福克海滩的沙丘打开,以及住宅2层古怪却精确的玻璃开窗方式,把海景框入室内。这种令人惊叹的类型学的颠覆——几乎把对复杂形式的结构主义感和对材料意义的狂热坚持组合起来,是JVA坚决无视潮流的一个例子。这是一个有趣又带危险性的项目,同时也联系、增加和颠覆了建筑的时间与地点。

感官的扭转

JVA建筑的一个共同特征就是对材料的兴趣,甚至达到痴迷的程度。不是斯堪的纳维亚设计的说教感,而是发自内心和玩的方式——作为氛围、美丽和愉悦的来源,而不仅仅展示材料或构造的清晰性。“我们从来也没有对这种建设真正感兴趣。对我们来说,它更多的是通过手工艺创造一种氛围”,哈康·维斯奈斯(Hakon Vigsnaes)说。如果这种兴趣将他们与同辈的北欧当代主义者区别开来,那么,这种兴趣也将他们与2000年代的国际实践密切联系。对气氛的兴趣已经成为最近10年的明显特征——对1980年代和1990年代过于理论化的建筑的一种反作用,甚至是反抗,或对新千年的极简主义反审美倾向的反抗。在沙丘住宅和最近刚完成的图滕(Toten)农场小屋项目中,JVA很明显在坚持着这种“感性转向”,打造出一座不仅服务于视觉感官也包括身体和其他感觉的建筑。图滕的这个新项目就是这种方法的一个实例。其壮观之处在于悬在挪威西岸最大的湖泊米约萨湖(Mj¿sa)之上,这个陡峭的地段,原来有两栋房子和一个巨大的谷仓。主要建筑在多年前被拆掉,南端的建筑还保存着,其被风化的木结构可以追溯到1830年。灰白的墙壁在白桦林背景的映衬下散发着耀眼的铜绿色,带给这个地方古老而奇特的宏伟感。那个谷仓在这个地区很常见;巨大的多功能坡顶结构,木结构地板,上层的木框架覆盖在垂直的挡雨板上。与该地区大多数谷仓不同的是,这个建筑从来没有被油漆过。它表面灰色和暖棕色的微妙变化赋予它美丽的铜绿光泽,就像那个老房子一样。而这个谷仓年久失修,必须要拆掉,但是,旧建筑的一些板材可以被重新利用。这个旧谷仓的板材则成为新建筑的出发点。新建筑将垂直于旧建筑的方向,并按照旧庭院的空间重新围合,这个正方形的体量,需要一个简单的单坡顶建筑,顺应地势。入口立面是对称的,大门上开了一扇窗,透过窗户的景色令人惊叹,视线可以穿过建筑直接望到下面蓝色的湖面和山峦。这座建筑表皮用旧谷仓的板材覆盖,而这些板材却有全新的利用方式。这些旧板材是楔形的,两端大小不同,传统的做法是交替地排列顶部和底部,而JVA则巧妙地利用了板材的宽度差,在立面上创造了一个扇形图案,从正门的两边呈放射状发散出去。在墙面上的这种惊人图案形成了一种风筒视画(trompe l’oeil)效果,使建筑转角看起来延伸出去,形成一种欢迎的近乎炫耀的姿态。建筑室内被米约萨湖面之上闪闪发亮的气氛萦绕;沿着河岸的丰富而保持完好的文化景观形成连续朝东的地平线。通过一个巧妙的三维规划,室内空间交织重叠。不同高度的室内和地面高度天衣无缝地编织在一起,使人在不经意间发现光线和视线的穿越。木框架结构暴露的斜梁径直穿过窗户,给室内一种突破常规的亮度。在室外,利用本地谷仓建筑表皮材料,使这个新建筑有一种奇特的亲和力,通常这种建筑的斜梁支撑木框架是暴露的。无礼性、独创性和娱乐性——根据条件提出创意解决方案(比如保留车库窗户的细节),陶腾别墅集中了古怪语境主义,对材料的感性使用,以及雅蒙德/维斯奈斯式独特的机会敏锐性。从不循规蹈矩,他们对场地条件充满了不懈的好奇,并把最惊人的发现转化成新奇而美妙的东西。

奇异的语境主义

北欧当代建筑为人称道的是它们对自然和场所的关注,但雅蒙德/维斯奈斯与众不同的是他们大胆的插入,而不是抒情的适应。他们的方式肯定不是基于语境的——或者说是奇异的语境主义,这种方式用一种不可预见和非常规的方法利用场地条件,并激发创新性。“我们通常发现保持场地的现有结构很有价值 ——不仅是经济价值”,维斯奈斯说,“它使你捕获更多的层次——使用和生活的层次,无论如何,这些是需要保留的重要部分。它提供了一种多样性,是无法凭空产生的。” 他们总是寻找在任何情况下的特别因素,用非常规的方式发现、组合和创新建筑,可以超越常规和传统。以惊人的方式叠加过去与现在,并顽强地拒绝它们的分离,JVA的作品在两方面都建树颇深。□

注释:

[1]埃纳尔·雅蒙德,“白色住宅”[J],2007, Domus,10 (907):70.

[2]雅蒙德/维斯奈斯, 迷失在自然. 展览编目,建筑设计,巴黎,2007

[3]克里斯蒂安·诺伯格-舒尔茨,场所精神:迈向建筑现象学. 纽约:瑞佐理,1980.

11 边缘住宅,夜景/Edge House, night view

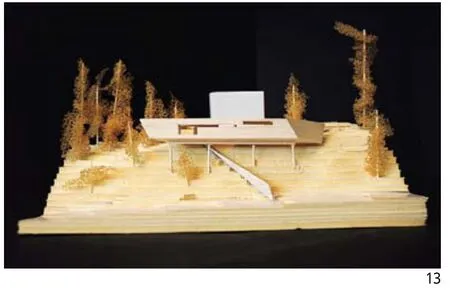

12.13 边缘住宅,模型/Edge House, model

11-13 摄影/Photography: Ni ls Petter Dale

Jarmund/Vigsnaes Architects cherish resistance.Their nightmare scenario is a commission with no limitations; with a boundless budget, a perfect site in a temperate climate, and a program determined by the architect him- or hersel f. Rather than looking for a smooth correspondence between architectural form and the many factors generating and af fecting it, they look for projects where site, situation, economy and program place dif ficult, even contradictory, demands on the architecture.“ We very much l ike the words‘resistance’ or‘ f riction’”, Einar Jarmund says“....in every commission we go out of our way to spot awkward conditions and tricky sites, restrictive law..s.so that they can later be turned into create points of depar ture.”[1]It is an approach which sets them apart from much Nordic architecture. In fact, in the at t imes oppressive landscape of Nordi“cpoetic modernism”, JVA’s work appears ref reshingly unpoetic. Their buildings are rebellious, refusing to submit neither to a particula‘r northern’ aesthetics nor to a predefined genius loci. Rather than contextual ly submissive, JVA’s architecture invents and re-creates the places it occupies“. We are constant ly aiming to explore the possibilities of friction between nature and structure” the architects declare in the exhibition catalogue Lost in Nature.

Established in 1996, made up by three partners and a workforce of around fifteen architects, JVA have already made their mark on the international architectural arena.Their work is published and exhibited wor ldwide, and they increasingly attract commissions abroad, for instance Living Architecture’s prestigious series of British summer houses, where JVA build alongside practices such as Peter Zumthor and MVRDV. A t ravel l ing exhibition of twelve major JVA buildings has crisscrossed back and forth between Europe and America since 2007, spurring a host of publications in books and magazines. Attempts at pigeon-holing JVA’s work,however, have given remarkably diverse resul ts. Their work and working methods bear t races of many‘schoo l s’, f rom Dut ch p ragmat ism to Swiss atmospherics, and f rom sleek Spanish abstraction to the quirky and expressive geometries of the American west coast of the 1990’s. In Norway, the practice has often been viewed as an enfante terrible, refusing to succumb to the dogmatic insistence on tectonic purity that has characterised Nordic modernism in the post war era. JVA themselves, however, are far too interested in architecture to devote themselves programmatical ly to any one approach or school.Instead, they cul tivate a cheer ful and undogmatic opportunism which is both refreshing and provocative.

Against nature

A particular character is of ten evoked whenever new, Nordic architecture is presented, involving the clarity of construction, the honest use of materials, and a general shunning of artifice. The blond wooden wal ls,the natural stone and the didactic clarity of the tectonic composition have remained the hal lmark of Nordic modernism ever since the hay-days of Scandinavian Design. Jarmund/Vigsnaes have not escaped this persistent mythology. Projects such as the Svalbard science centre has been presented as the realization of a northern genius loci-a pristine and natural response to the rough wilderness of the far north. Nothing, in fact,could be further from the truth. To be sure, JVA’s architecture is informed, inspired, and conceived in relationship to nature. Many of their works are situated in exquisite natural sites-f rom the arid arctic landscape of Svalbard to the explosively lush river val ley of the Red House. Yet there is nothing ‘natural’about the precise geometry, the careful manipulation of materials and colours, or the highly cultivated plans,sections and facades of JVA’s buildings. The twisted copper-clad volumes of the Svalbard research centre,for instance, with is slit-like widows, its gleaming body and its oblique geometry, are products of a design process in which form and function, site and climate,are brought together in a fruitful and friction-fil led relationship, defying and enduring nature rather than mimicing it. As the architects describe the little cabin in Nordmarka, a woodland region north of Oslo: “Placed in a clearing in a deep forest, the cabin doesn’t real ly relate to its present local piece of ground but rather to the soft hil ls and lakes towards the south horizon.”[2]The denouncement of the local ground and invocation of wider horizons for their architecture should be read as a programmat ic statement. JVA cul t ivate a sophisticated and many-layered artificiality, made meaningful more in contrast to nature than as its continuation or imitation. “The previous generation of architects had a completely dif ferent earnestness in the way they approached nature” says Alessandra Kosberg. “We don’t treat nature as a religion but as something you can use, actively.”

Redef ining place

If‘nature’and the‘natural’has been a persistent obsession in modern Norwegian architectural discourse, it is rival led only by the closely related concept of ‘place’. The architectural thinking of the historian and theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz revolved around the genius loci-the spirit of the place-a concept der ived f rom his decisively essentialist interpretation of the natural landscape.[3]Norberg-Schulz’s topographical determinism with its idea of architecture as a mimetic re-enactment of the landscape, has been a powerful inf luence in Norwegian architecture, f rom Sverre Fehn and Wenche Selmer to the innovat ive contextual ism of contemporary practices such as Car l-Viggo H¿lmebakk or Knut Hjel tnes. How does Jarmund/Vigsnaes fit into this picture? Not seamlessly, at any rate. “We cultivate not one, but a whole series of strategies towards nature and towards place. Some of them are perhaps‘poetic’ in some sense-some are definitely not. We are more concerned with the particular commission and its unique conditions, than with cul tivating one particular approach in our architectur”e says Jarmund.Houses such as the Edge House, the White House and the Triangle House i l lust rate this contextual opportunism. Al l three houses are buil t on dif ficult sites, either because the topography is impossibly steep as in the Edge House, or because the sites are squeezed into dense suburban situations with confined sight lines and restrictive building regulations, as in the White House and the Triangle House. Rather than thwarting the design, however, the restrictions have triggered creative solutions. In the Edge House, the steep si te p romp ted a unique, cant i levered construction tiptoeing over the landscape with spindly steel column legs. In the White House the tight suburban situation caused the house to twist and turn, directing itself like a telescope towards precisely defined views.In the Triangle House, the strict regulations on height and area produced a highly unconventional volume,al lowing for an innovative modulation of l ight and space. These are ingenious little buildings. Their scale and materiality are nothing out of the ordinary, yet their geomet rical precision, careful ly composed openings and restricted range of materials, give them a remarkably sculptural presence. Like the TurtaHotel, the Cabin in Nordmarka, and many other projects, JVA’s buildings insert themselves itsel f into the landscape with a quirky lightness rather than with bombastic“contextual” gestures. Not for a second miming a predefined genius loci, they nevertheless picks up on mul tiple contextual strands and weave them into a completely new fabric.

A good example of JVA’s quirky contextualism is the recent ly completed Dune House, in Suf folk,England. One of a series of summer houses developed across Britain by the charity Living Architecture, it sits just at the edge of the picturesque coastal vil lage of Thorpeness. Drawing on their own holiday memories of the shabby quaintness of English Bed & Breakfasts,JVA have presented an idiosyncratic interpretation of the suburban Eng l ish house. Decomposing the characteristic hal f-dormer silhouette into a strange and edgy composition, they operate on a thin line between a recognizable typology and its sur real transformation. If the house transforms certain aspects of the place, however, it links very direct ly onto others, like the way the glass base opens directly onto the sand dunes of the Suf folk beaches, and the quirky but precise window openings in the second f loor frame and reveal the sea view. This surprising typological subversion-combining an almost deconst ructivist sensibility to complex form with a rabid insistence on material meaning-is an example of JVA’s stubborn disregard for trends. It is a fun-loving, risk-taking project, simul taneously connecting to, adding to, and subverting its time and its place.

The sensuous turn

A noticeable feature of al l JVA’s buildings is an interest-obsession even-with materiality. Not in the didactic sense of Scandinavian Design but in a far more visceral and playful way-as a source of atmosphere, beauty and pleasure, rather than material or tectonic legibility. “We have never real ly been interested in construction as such. For us it is more a matter of crafting an atmosphere” says Hakon Vigsnaes.If this interest sets them apart from many of their Nordic contemporaries, it does inscribe them deeply into international practice of the 2000’s. The interest in atmosphere has been palpable in the recent decade -

a reaction, perhaps, against both the over-theorized architecture of the 1980’s and 1990’s, or against the aesthetic anorexia of the turn-of-the-mil lennium minimalism. With works such as the Dune House and the recently completed vil la at Toten, JVA certainly adheres to this‘sensuous turn’, cul tivating an architecture attuned not only to the eye, but to the body and the senses. The new vil la at Toten is a par t icul ar ly good example of this approach.Spectacular ly situated high above the west banks of Norway’s biggest lake, Mjsa, the steep site original ly contained two houses and an immense barn. While the main house was torn down many years ago, the southernmost house is stil l standing, a weathered wooden structure dating back to the 1830’s. Its graying wal ls provide a rich patina against the green birch forest behind, giving the place an ancient and curiously majestic feel. The barn was typical for the region; a huge, mul ti-purpose pitched roof st ructure with timbered ground f loor and a timber frame upper storey,clad in vertical wooden weatherboards. Unlike most barns in the area, this one had never been painted. Its subt le variation of greys and warm browns gave it a beautiful patina, akin to the old house. It was, however,in a bad state of disrepair and had to be taken down,which made bits and pieces such as the cladding available for reuse. The old barn panel became a point of departure for the new house. Placing the building perpendicular to the old house to regain the old courtyard, the rectangular volume sports a simple monopitched roof, sloping with the terrain. Its entrance facade is symmetrical, the main door contained within a window which af fords a stunning view right through the house, onto the blue lake and rol ling hil ls below.The house is clad in the old barn panel, yet the panel is used in total ly new way. For while the old panel with its wedge-shaped top-root variations was traditional ly leveled by alternating tops and roots, JVA utilized the uneven board widths to create a fan-shaped pattern in the facade, radiating out from either side of the f ront door. The striking pattern on the f lat facade creates something of a trompe l’oei l ef fect, making the corners appear to stretch out in a welcoming, almost baroque gesture. The interior is dominated by the shimmering, ethereal view over Mjsa; the fertile and wel l kept cul tural landscape along its banks forming an unbroken horizon towards the east. In a cunning piece of three dimensional planning, the interior spaces inter lock and over lap. Rooms of varying heights and f loor levels weave into each other in a seamless way,always af fording glimpses of light and view through and across. The exposed diagonals of the timber f rame construction run straight across window openings,giving the house an informal lightness. From the outside, it lends the building a curious af finity with the local barn-architecture, in which diagonal ly suppor ted wood f rame constructions are of ten lef t exposed. Irreverent, ingenious and playful-inventing solutions (such as the highly original window details of the garage) as occasion requires, the vil la at Toten sums up both the quirky contextualism, the sensuous use of materials, and the particular opportunistic acumen of Jarmund/Vigsnaes. Never submit ting to dogmas or trends, they grab hold of the given with untiring curiosity, turning the most surprising find into something new and beauti ful.

Qui rky contextual ism

Contemporary Nordic architecture is often praised for its particular attunedness to nature and place, yet Jarmund/Vigsnaes Architects stand out more for their bold insertions than their lyrical adaptations. Their approach is certainly not a-contextual-rather one could speak about a quirky contextualism in which the qualities that exist on a site or in a situation are used in unexpected and undogmatic ways, as inspiration for the new. “We often find that retaining existing structures on a site has a value-not just an economic value” says Vigsnaes:“It allows you to capture more layers-layers of use and of life, which are important to retain, somehow. It gives a mul tiplicity which is impossible to generate f rom scratch.” Always looking for the specific qualities in any situation, they find, invent and combine things in a manner which overturn both expectations and conventions.Superimposing the past and the present in surprising ways, doggedly refusing their separation, JVA’s works add to the depth of both. □

Notes:

[1]Einar Jarmund, “White House”[J], 2007, Domus,10 (907) :70.

[2]Jarmund/Vigsnaes, Lost in Nature. Exhibition catalogue, La Galerie d’Architecture, Paris 2007.

[3]Christian Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizol l i,1980.