Chinese Black Pottery Art

WU BING

AT the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, China showed the world four national treasures projected on a spectacular scroll, one of which was the eggshell black pottery goblet.

The goblets black surface still glitters after 4,000 years. It is as thin as an eggshell, and tapping it produces a sound pleasing to the ear. The cup showcases exquisite ancient workmanship, and is extolled as the best representative of a 4,000-year-oldhandicraft.

It is said that the black color was not intentional but was the result of faulty kiln temperature control during firing. Despite being born in error, it is its color that gives the earthenware a sense of timelessness, mystery and dignity. In contrast to other earthenware, black pottery has never been used for functional purposes. In early times, black pottery works were mainly used in ritual sacrifices. Potters created them to sanctify the spirits and appease the Gods.

Teetering on Extinction

In 1928, numerous potteries produced 4,000 years ago were unearthed at Longshan Town in Zhangqiu City, Shandong Province. Among them was a black earthenware piece of a kind never seen before, which instantly drew the attention of reputed archaeologist Wu Jinding (1901-1948). It was as black as pitch, lustrous and eggshell thin.

Although black pottery is some 4,000 years old, the skills involved in its making were lost for several thousand years until reconstituted in the 1950s. Pottery is generally made by forming the clay body into the required shape and then baking it in a kiln. Black pottery is shaped from a ball of clay on a rotating turntable. The raw clay needs to be carefully selected, put through a well-knitted sifter, and mixed with sand or kept pure, according to practical demands. After air bubbles are forced out, it is mixed and squashed by being walked on. The clay object can then be wedged into greenware. When the greenware becomes half dry, it is suitable for decorating and incising. When completely dry, the greenware should be burnished by mussel shells and put into a kiln for firing.

The quality of the clay plays a vital part in black pottery ware. Ordinary clay is bone-dry and hence can be easily broken. Due to its thin clay body of only 0.2 mm, glazed black pottery looks very alluring.

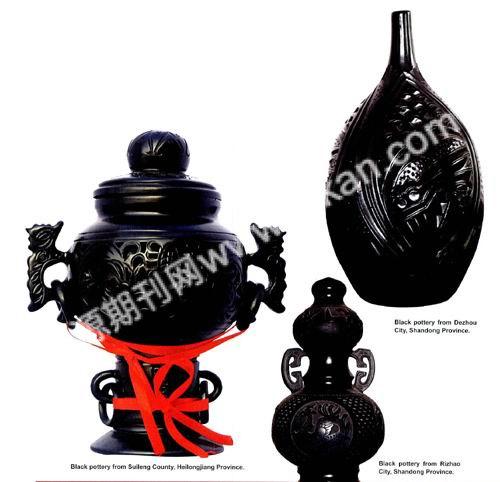

Black pottery comes in many types. In its early period, artifacts included ding (a three- or four-legged vessel for ritual sacrifices), plates, bowls and li (ancient Chinese cooking ware). Later categories included pots, kettles, zun (a wine vessel with a vase-like form), jue (a three-legged wine pitcher), and human and animal likenesses. These types were later reproduced in a range of Chinese bronze ware.

Black pottery cannot be as elaborately painted as colored pottery. The main means of decoration are “piercing,” “decal” and “bow-string patterning.” Black earthenware, simple looking and similar in terms of shape and decoration patterns, embodies the arts enduring charm.

Modern Development

In Suileng County, Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China, an old craftsman named Kou Hualin (1901-1984) worked in an ordinary earthenware factory. It was he who happened to discover the method of firing black pottery.

Kous family had been engaged in earthenware firing for generations. As a little boy, he learned the skill from his elders at a time when production mainly focused on grayish and red pottery, in the form of flowerpots and other earthernware. Through practice, Kou improved the consistency of his pots. Besides painting and carving, he also used the techniques of single layer and double-layer openwork in his decorations, making his pieces popular with local customers.

One summer day there was a sudden downpour. Kou immediately ran to his kiln, which held a group of pots nearing completion. He found the kiln drenched and full of smoke. He covered it with firewood and culms, expecting the rain would soon stop and he would be able to open the kiln and finish the half-done work. It was three days before the rain finally stopped. Kou dejectedly removed the temporary cover, ready to find a kiln full of ruined pots. To his astonishment, all the pots were still intact, and some had turned black and lustrous as pitch.

Kou became very excited at this unexpected development. He constructed a smaller kiln especially for further trials. Over 40 years of research and practice, he finally made a breakthrough in firing which became known as the high-temperature carburization technique.

Kou Hualin had little schooling and had never heard of Longshan Culture, let alone the fact that the carburization of chinaware using high temperatures and thick smoke relies on the principle of ion permeability. Rather, he developed black pottery art under the impetus of life. His pottery creations were also inspired by folk arts like papercuts, embroidery, furniture incising and door-god pictures.

If Kou Hualin is considered to be the inventor of modern black pottery, Liu Jiadi took the artform to the wider world. Without his foresight, the black pottery of Suileng County would not be prevalent over such a large area.

When Kou Hualins earthenware was displayed at the First Heilongjiang Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1961, Liu Jiadi, a cadre of the Arts and Crafts Department of Heilongjiang Provincial Handiwork Administration Bureau, showed a keen interest in the black pottery works. Soon after, he paid a special visit to Suileng Countys earthen pot factory, and offered guidance on pottery production. He helped Kou Hualin integrate and articulate his pottery types and decoration patterns, and then open a training program. He also provided Kou with plenty of valuable references. Moreover, he made many rubbings of Kous representative works, and offered critiques of those in need of improvement.

Liu Jiadi elevated the workmanship and quality of black pottery, and showcased it in a national ceramic exhibition. The nation soon became fascinated by the style. In every province of China, craftsmen of the Kou Hualin “school” have devoted their efforts to black pottery production and steadily advanced the artform.

Min Wei, a craftsman in Longshan Town, Zhangqiu City of Shandong Province, began his experiments with the form early in 1998. In the autumn of that year, after several thousand failures, he finally produced an eggshell-thin pottery cup, like those mentioned in historical records – a significant breakthrough in modern black pottery. The 22cm-high cup only weighed 18 grams, making it comparable to the 4,000-year-old unearthed find.

In June 2007, Su Zhaoqi, a black pottery craftsman of Rizhao City, Shandong Province, successfully fired his black pottery work Olympic Ding, which is a replica of ding produced in the Shang Dynasty. It was 2.66m high and 1.5m in diameter, with a wall 2cm thick and weighing 600 kg, making it the largest black pottery ding in the world. Su Zhaoqi presented it to the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of XXIX Olympiad.