Classical Private Gardens of Jiangnan

This book is a classic work for the study of classical Chinese garden art, showing a unique Chinese classical life interest and highlighting the Chinese aesthetic taste that integrates the past and the present. It is an elegant reading material to understand classical beauty, the beauty of art, and the beauty of life in the south of the Yangtze River, a Chinese story in the garden.

When evaluating and appreciating the Jiangnan private gardens that have been preserved to this day, several distinctive characteristics often emerge.

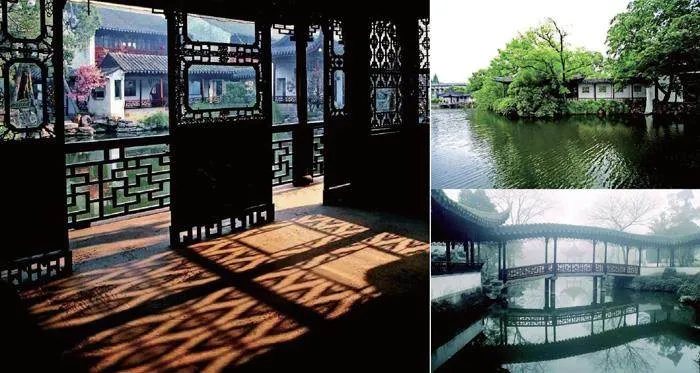

First, grandeur in smallness: achieving more with less. From their locations, most private gardens are connected to residences or mansions, forming urban courtyard gardens or adjacent residential gardens. In the scenic suburbs with picturesque landscapes, there are also private gardens, but their owners typically have main residences in the city, using the gardens as seasonal retreats for spring flower viewing, summer cooling, or autumn moon gazing. These are villa-style gardens. With the exception of a few gardens owned by high-ranking officials or the wealthy elite, most private gardens, whether in the city or suburbs, occupy relatively small areas. Larger gardens span around ten mu (approximately 1.6 acres), while smaller ones cover only a few mu. This is reflected in the names of many surviving literary gardens. For instance, in Suzhou, there is the Hu Garden (Teapot Garden), which is named after its compact layout and resembles a teapot. Other renowned gardens, such as the Canli Garden (Remnant Grain Garden), Jiezi Garden (Mustard Seed Garden), and Banmu Garden (Half-Mu Garden), are all famous for their modest size. Though limited space may seem unfavorable for garden construction, ancient garden designers mastered the dialectical principles of art creation, turning disadvantages into advantages. They excelled at leveraging “smallness” to their benefit, meticulously designing and arranging the space to create boundless scenery within a finite area, achieving the effect of grandeur in smallness and abundance with minimalism. The saying, “With three or five steps, one traverses the world; with six or seven companions, one commands a grand assembly,” often used to describe the artistic finesse of Chinese classical opera, applies equally to literary gardens. These gardens aim to represent the beauty of the vast world within a limited scope, adhering to the artistic principle of “one embodying ten.” Every element of the garden, whether it is rockeries, ponds, pavilions, corridors, bridges, or even a corner of a courtyard, emphasizes delicacy and pictorial quality. The placement, arrangement, and orientation of each feature undergo repeated refinement to achieve the artistic effect where less conveys more, simplicity amplifies intensity, and sparse imagery evokes profound meaning.

The second hallmark of Jiangnan private gardens is their rich literary essence and scholarly aura. Due to their generally modest size, these gardens lack the grandeur and magnificence of imperial gardens, but they possess a unique charm that captivates visitors. The key lies in the way the garden’s design reflects the cultural sophistication and literary refinement of its owner. The higher the owner’s intellectual and artistic attainments, the more the garden embodies poetic and literary qualities. During the initial stages of garden design, owners often approached the process with the same care and creativity as composing poetry or writing prose. Qian Yong, a garden critic of the Qing Dynasty, observed parallels between garden design and literary creation in the conceptualization and layout of Jiangnan literary gardens. Visiting a well-crafted literary garden evokes a sense of artistic vitality, where every mountain, stream, plant, tree, pavilion, or hall appears meticulously crafted, akin to the precision required in refining words in poetry. Each element is thoughtfully positioned — some hidden, some revealed with a balance of curves and straight lines, creating a harmonious composition akin to a poetic landscape. A representative example is Suzhou’s Wangshi Garden, one of the most notable small private gardens in Jiangnan. Within this garden, the study courtyard, “Dianchunyi,” epitomizes the essence of classical Chinese garden design. It has even been reconstructed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where its elegant style and exquisite craftsmanship have garnered widespread acclaim.

Another defining feature of Jiangnan private gardens is their understated elegance. In traditional Chinese aesthetics, “elegance” refers to tranquility, naturalness, freshness, simplicity, and unpretentious grace.

“Simplicity” emphasizes rusticity, antiquity, and plainness, avoiding excessive ornamentation or intricate designs. The balance of elegance and simplicity is closely tied to the principle of achieving more with less and preferring simplicity over complexity. In function, private gardens serve as places for rest, contemplation, and reading, which is why their landscapes are typically serene, refined, and naturally fresh. Unlike the vibrant and eye-catching colors often found in imperial gardens, private gardens feature subtle hues. The buildings are typically uniform in style, with gray-tiled roofs and whitewashed walls. Wooden elements are often in deep brown tones. The bases of terraces and paved pathways are constructed from plain materials such as gray bricks, slate, or even simpler options like pebbles, broken bricks, or tiles, with patterns such as lattice designs, crack patterns, or simple plant-inspired motifs. Interior furnishings often include elegant and antique artworks. Even the plaques and couplets used to decorate garden scenes are simple yet tasteful, often crafted from wooden panels or split bamboo with engraved inscriptions, blending naturally with the garden’s aesthetic. While Jiangnan private gardens have more buildings than other types of gardens, these structures are typically integrated with the natural landscape, except for the main halls. Traditional symmetrical courtyard layouts progress step by step in harmony with the garden’s structures. Examples include the “Begonia Spring Cottage” in the Humble Administrator’s Garden and the “Greeting the Peak Pavilion” in the Lingering Garden, which feature unconventional architectural designs — one and a half rooms or two and a half rooms — breaking away from the standard odd-numbered configurations of three, five, or seven rooms.

Plant landscaping, particularly in the literary private gardens of Jiangnan, is meticulously curated. Local tree species that are easy to cultivate and maintain are preferred, with emphasis on those possessing elegant forms and requiring minimal upkeep.

The fourth defining feature of Jiangnan private gardens is their adaptability to local conditions and focus on creating distinctive garden aesthetics. In terms of layout and landscaping, these gardens often eschew conventional formulas, tailoring their designs to the specific environmental conditions of each site. This approach allows each garden to showcase its unique personality and charm. Ancient scholars, with their refined aesthetic sensibilities, appreciation for natural beauty, and extensive travel experiences, intuitively followed natural principles when designing gardens. They adeptly harmonized the relationships between rocks, water, and plants within the garden, prioritizing quality over quantity and emphasizing a coherent theme or unique identity. This philosophy aligns with the traditional Chinese literary ideals of naturalness, freshness, and avoiding clichés while pursuing spiritual resonance and vitality. Each celebrated garden scene was carefully crafted according to its environmental context. For example, Suzhou’s world-renowned gardens share the general style of Jiangnan’s water-town aesthetics, yet each retains its distinct individuality: The Humble Administrator’s Garden (Zhuozheng Yuan) uses water as its main element, with simple and elegant architecture that exudes a rustic, serene charm. The Lingering Garden (Liu Yuan) balances mountains, ponds, and architecture, offering intricate courtyards with quiet elegance and pavilions that are ornate yet tasteful. The Garden of the Master of the Nets (Wangshi Yuan) excels in its compact and secluded design, with tightly knit structures creating an endless sense of discovery. The Canglang Pavilion (Canglang Ting) stands out for its antiquity and tranquility, embodying the rugged appeal of untamed nature. Among the garden elements, the most striking are the rock and water features, showcasing extraordinary variety in their combinations. In the Humble Administrator’s Garden, harmony prevails. From the main hall, Yuanxiang Hall, one can look north to see two mountain islands in the central pond, where their flat ridges and rocky shores mirror one another, creating a scene of balanced elegance. In contrast, the Jichang Garden in Wuxi features a dramatic interplay of stone and water. Its grand Yellowstone artificial mountain presses closely against the pond known as Jinhuiyi, where cliffs rise sheer from the water’s edge. A winding path hugs the cliff face, tracing a route that feels like navigating through a gorge. The Canglang Pavilion takes an entirely different approach. Instead of creating small ponds and hills within its limited space, the entire garden is dedicated to a single large earthen and stone mountain. The water, ingeniously borrowed from the surrounding landscape, flows into the garden from a boundary river. The design eliminates high walls at the garden’s edge; instead, a meandering corridor follows the mountain’s contours, blending seamlessly with the water. The corridor features a waterside pavilion and a fishing terrace, uniting the interior and exterior landscapes in poetic harmony. This is a masterpiece of the landscape scenery of Jiangnan literary gardens. These examples illustrate how Jiangnan’s ancient literati infused their gardens with the same focus on unique style and individual expression that they brought to their poetry and painting. This emphasis on distinctiveness remains a crucial aspect of their gardens’ enduring appeal and deserves special attention when appreciating them today.

The final defining feature of Jiangnan private gardens lies in their ability to seamlessly integrate recreational and residential functions within a relatively small space, achieving a harmonious unity of “leisure” and “living.” In ancient times, engaging with scenic landscapes and enjoying natural beauty were described as “游” (yóu, leisure), while activities such as reading, practicing arts, engaging in intellectual discourse, and hosting gatherings within a scenic environment were considered “居” (jū, living). Achieving both these realms was regarded as the pinnacle of artistic perfection. Northern Song Dynasty painter Guo Xi once stated that landscape scenery could be classified into four levels: “可行” (ke xing, accessible), “可望” (ke wang, viewable), “可游” (ke you, explorable), and “可居” (ke ju, livable). Only when a landscape reached the levels of “explorable” and “livable” could it be deemed a masterpiece. China’s rich natural landscapes and famous scenic spots have captivated countless literati and artists throughout history. Traveling through mountains and rivers became a popular trend. However, few individuals, apart from hermits or monks, were willing to fully retreat to isolated natural environments. Ancient scholars often found themselves torn between their desire to immerse in the beauty of nature and their attachment to the comforts of urban life. Through the ingenuity and meticulous planning of garden designers, this apparent contradiction was reconciled. The private gardens adjacent to urban residences epitomize this harmonious balance.

Ruan Yisan

Ruan Yisan is a professor and doctoral supervisor of Tongji University, director of the National Research Center for Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, a member of the Expert Committee of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, and a librarian of the Shanghai Research Institute of Culture and History.