Starting with Xie He’s “Record of Ancient Paintings”

This book is written by Mr. Chen Chuanxi, a famous art historian, from the three aspects of theory, painting method, and evaluation, to analyze the essence of painting and combine history and theory to form eight essays on the study of the painting theory of the Six Dynasties and eight punctuation and annotations of the famous painting theory of the Six Dynasties.

1. The Importance of Xie He’s Conclusions

The Six Dynasties period witnessed not only one art critic but also several non-specialist commentators, who offered varying degrees of evaluation of Gu Kaizhi. Among these critics, Xie He stands out as the most authoritative and rigorous figure in art history, a fact that is beyond dispute. However, previous interpretations of Xie He’s insights have often been flawed, sometimes even completely reversing his intended meaning. Truly understanding Xie He provides a clear framework for appreciating Gu Kaizhi’s work.

Xie He’s theory of the “Six Principles” (Liufa) continues to play a significant role in painting creation and critique, even today. This is no trivial matter. Subsequent critics invariably used the “Six Principles” as a foundation for their discussions on painting. Between Gu Kaizhi’s time and Zhang Yanyuan’s writings, spanning approximately four centuries, Xie He remained unparalleled as a critic. For such a perceptive critic, his assessments deserve our full attention.

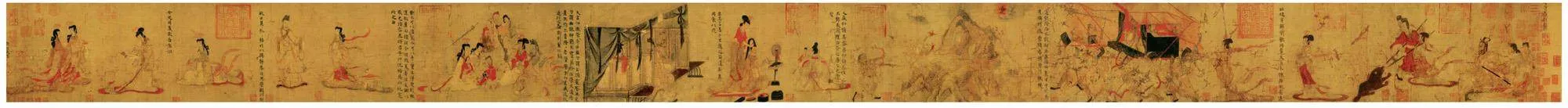

Xie He classified the works of 27 (originally 28) painters from the Sun Wu period to the fourth year of the Liang Dynasty’s Zhongdatong era (532 CE) into six grades. He placed Lu Tanwei’s paintings in the top grade and ranked him first. Xie He stated that Lu Tanwei’s works completely captured the qi yun (spiritual resonance) of his subjects, achieving unparalleled vividness while never wasting effort on non-essential details. His works reached the pinnacle of artistic value. There was no category higher than the “top grade,” and Lu Tanwei was ranked first within this grade. Xie He even believed this ranking was an understatement of Lu’s mastery. In contrast, Gu Kaizhi’s paintings were ranked in the third grade, below those of Yao Xiandu. The gap between Gu’s paintings and Lu’s was so great that Yao Xiandu, ranked first in the third grade, received much higher praise than Gu Kaizhi. Xie He’s evaluations were based on firsthand observation of their works. That Xie He rated Gu Kaizhi so poorly is a matter that demands our serious attention.

2. Gu Kaizhi’s Renown

The reason Xie He’s evaluation of Gu Kaizhi did not become definitive is that Gu Kaizhi’s reputation was exceedingly high. Gu was a celebrated figure of his time, praised as being “peerless in talent, eccentricity, and painting.” References in works like Shishuo Xinyu (A New Account of the Tales of the World) and Shipin (Poetry Criticism) highlight Gu’s “peerless talent,” primarily lauding his literary achievements.

The so-called “peerless eccentricity” was, in fact, a reflection of Gu Kaizhi’s philosophy of self-preservation. Given the unique sociopolitical climate of the Jin-Song period, it was not uncommon for intellectuals to feign eccentricity or “madness” to avoid political entanglements and protect themselves. Based on historical accounts, Gu’s “eccentricity” could indeed be described as “peerless.”

In the realm of painting, the earliest admirer of Gu Kaizhi was Xie An, a prominent figure of the Wang and Xie clans during the Jin Dynasty and a key political leader of his era. Xie An directed the victory at the Battle of Feishui, securing the Southern Jin court’s hold on Jiangnan. Apart from his military and political achievements, Xie An was also known for his refined lifestyle, enjoying chess, poetry, and leisure outings with courtesans, making him a central figure of discussion in his time. Before Xie An held significant power, he served as a subordinate to Huan Wen, under whose command Gu Kaizhi also worked. Both men served in the same administrative office, but Gu’s relationship with Huan Wen was particularly close. It was during this period that Xie An reportedly remarked on Gu Kaizhi’s paintings, saying they were “unprecedented throughout human history.”

The context and intention behind Xie An’s remark remains unclear. Was it a polite compliment, a casual comment, or a sincere evaluation? We can analyze it from various angles. However, regardless of the intent, Xie An was not a professional art critic, and his opinions did not carry the same weight as those of Xie He. Nevertheless, Xie An’s influence far exceeded that of any critic of his time. His words carried immense authority. For example, even his nasal condition, which caused him to speak with a muffled tone, led admirers—including prominent figures—to imitate him by covering their noses while speaking. Once Xie An’s praise of Gu Kaizhi spread, its impact was significant and widespread. The tendency for people to favor hearsay over personal observation is a universal phenomenon. At the time, painters like Lu Tanwei and Zhang Sengyou had yet to emerge, and the only known work by Cao Buxing—a single dragon head painting—was hidden in an imperial treasury. Meanwhile, Dai Kui lived in seclusion and refused to cooperate with or endorse the ruling authorities, even openly criticizing them, which meant he received little public attention. In contrast, Gu Kaizhi enjoyed associating with influential elites, and the clamor surrounding his name only grew louder. However, when faced with a discerning critic like Xie He, Gu could not rely on the noise of public acclaim to shield himself. Xie He’s unique and unconventional perspective prevented him from being swayed by popular sentiment. Yet, Xie He’s decision to rank a highly esteemed artist like Gu Kaizhi so low stirred considerable controversy. The first to rise in opposition was Yao Zui.

3. Yao Zui’s Evaluations

Yao Zui’s standing and influence in art history, especially his approach to art criticism, differ significantly from those of Xie He. Unlike Xie He, Yao Zui was neither a painter nor a professional art critic. Moreover, his involvement in political struggles ultimately led to his demise amid harsh political conflict.

When Yao Zui authored Xu Huapin (Continuation of the Rankings of Painters), he was merely 15 or at most 20 years old. In contrast, Xie He had already become an experienced and accomplished critic by the time he wrote his work. Naturally, we should neither dismiss Yao Zui for his lack of fame nor reject his views outright because of his youth, but instead evaluate the validity of his arguments. Yet Yao Zui’s critique mainly revolves around Gu Kaizhi’s reputation, and his arguments lack depth or substance. He neither elucidates the strengths of Gu Kaizhi’s art nor the shortcomings of others’ works, making it difficult to find his claims convincing.

Yao Zui’s approach to evaluating art relied heavily on two flawed principles: first, judging art based on an artist’s reputation, and second, assessing individuals and their art based on their social standing. This lack of an objective, fact-based perspective weakens his credibility. His high praise of Emperor Yuan of Liang (Xiao Yi) also failed to garner much approval from others. Furthermore, the artistic stature of Xun Xu, Wei Xie, Yuan Qian, and Lu Tanwei was consistently regarded as superior to that of Xiao Yi.

Compared to Yao Zui, Xie He demonstrated a much higher level of critical insight and seriousness. Yao Zui’s rebuttal of Xie He’s evaluations lacks any compelling arguments, making it unreliable. In contrast, Xie He’s critiques carry far greater weight. (Supplementary Note: This essay was written in 1980. Subsequently, my opinion of Yao Zui has shifted slightly, albeit limited to his contributions to art theory.)

4. Xie He’s Evaluations

Following Yao Zui, other critics such as Tang Dynasty figures Zhang Huaiguan and Li Sizhen also opposed Xie He’s assessments. However, their arguments were largely constrained by Gu Kaizhi’s formidable reputation, and they failed to present substantive reasoning.

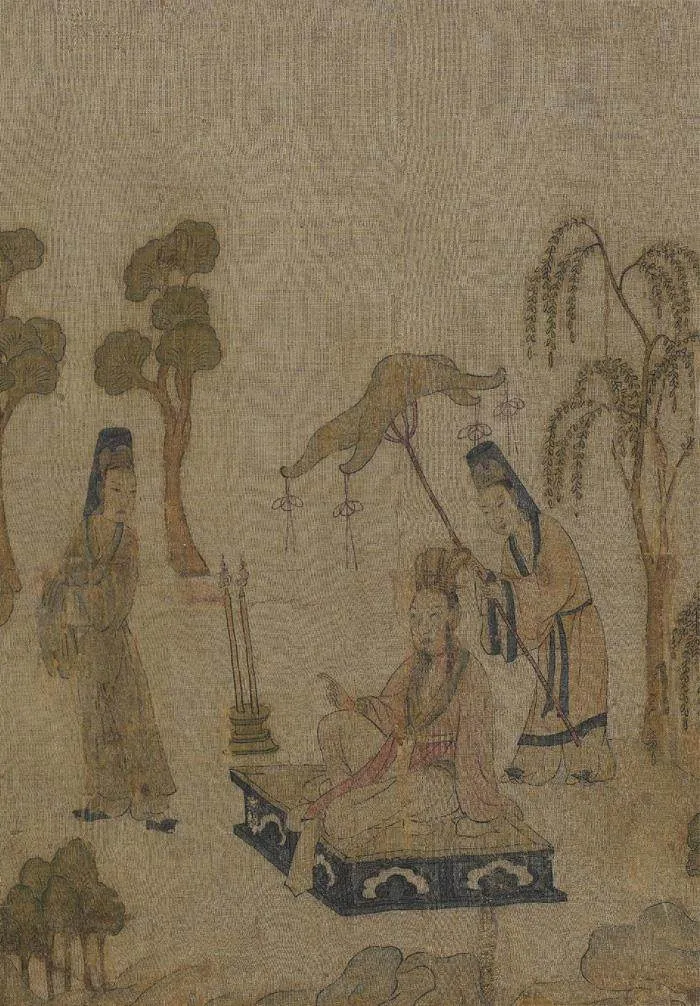

Was Xie He deliberately antagonistic toward celebrated figures by ranking the highly renowned Gu Kaizhi as third grade and imperial artworks as fifth grade? Not at all. For instance, Xie He placed Lu Tanwei at the top of the first grade, followed by Cao Buxing, whom he praised with the words, “Observing his vigor and form, his reputation is well-deserved.” Clearly, while Cao Buxing was a renowned figure, Xie He still acknowledged his work as worthy of his fame. Similarly, the first grade included Xun Xu, an illustrious and politically powerful aristocratic painter from the Wei and Jin periods. (Xun Xu was a key member of the Sima faction, playing a pivotal role in the decision to pacify Shu, as documented in the Book of Jin.) Xie He’s evaluations were evidently not influenced by status or reputation. Let us now carefully revisit Xie He’s critique of Gu Kaizhi and assess its validity. Xie He remarked that Gu had a profound, precise, and subtle understanding of what should be expressed in painting, a quality primarily reflected in Gu’s theoretical writings. The phrase “he never misplaces a brushstroke” highlights Gu’s meticulousness and dedication. This is evidenced by anecdotes such as his taking days before adding the finishing touches to a subject’s eyes or his prewriting and repeated refinement of concepts before painting Mount Yuntai. However, Xie He also stated, “His strokes fail to match his intent,” meaning that Gu’s paintings could not fully convey his artistic vision or achieve the ideal state he sought. A notable example is Gu’s Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies. In the first section, portraying Emperor Yuan of Han, the figure fails to exhibit the energy of being locked in combat with a bear. Similarly, the expressions of the two ladies-in-waiting lack any trace of fear or shock. Another scene, Sharing a Quilt in Doubt, where a man and woman are depicted sitting together on a bed, is similarly obscure and leaves viewers perplexed. Zhang Huaiguan’s comment, “Do not seek meaning between the images,” aptly underscores this shortfall. When one closely examines Gu’s works, Xie He’s observation of Gu being “overpraised relative to his actual merits” becomes evident. Xie He himself likely held initial expectations based on Gu’s fame but was ultimately disappointed upon seeing his works, prompting such a frank evaluation.

Xie He’s four comments about Gu Kaizhi are neither hollow rhetoric nor baseless flattery, much less unwarranted attacks.

Criticism of genius by mediocrity has always been a common phenomenon. The “shallow and vulgar” critiques of Xie He by later detractors are but one example of this. However, we should never dismiss the insights of genius in favor of siding with mediocrity.

Chen Chuanxi

Chen Chuanxi is a well-known art historian and art critic. He is a professor and doctoral supervisor of the School of Arts, Renmin University of China. He is an expert in fine literature, ancient literature, poetry and literature, good calligraphy and painting, and has been engaged in science and technology for many years. He is currently working on Chinese art history and humanities history. He has published more than 70 academic works.