Embellishing the Years: Stories of Chinese New Year’s Paintings Along the Grand Canal

This book starts with the two main focuses of New Year’s paintings and canals, with Yangliuqing (Green Willow) in Tianjin as the center, north to Tongzhou, Beijing, and south to Dezhou in Shandong, Xuzhou and Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, Hangzhou in Zhejiang, and then radiates overseas. This book is divided into five chapters vividly telling the meaning of traditional Chinese culture conveyed by the wonderful Danqing pen on the Grand Canal, as well as the collision and combination of the art of New Year paintings in the historical process inherited to the present.

“In every bustling area during the twelfth lunar month, straw booths are set up to sell paintings. Women and children eagerly buy them to adorn their new year.”

— Fu Cha Dun Chong, Records of Seasonal Customs in Beijing, Qing Dynasty

After Laba Festival (the eighth day of the twelfth lunar month), households across China begin their preparations for the New Year.

In Tianjin, the Temple of the Queen of Heaven has long been the hub of New Year festivities. The vibrant New Year market offers paper-cutting, couplets, window decorations, hanging ornaments, and auspicious paintings, creating a dazzling array of colors and designs. For people celebrating the New Year, the most important part isn’t food, drink, or attire — it’s the enthusiasm and hope for a better life.

When it comes to adorning the years, New Year paintings, filled with heartfelt aspirations, provide the most ideal colors.

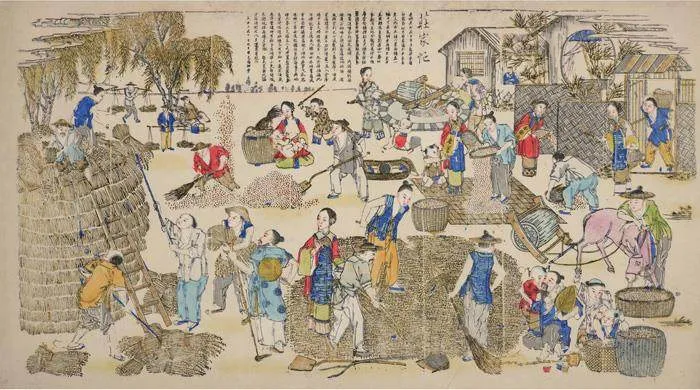

In the agrarian era, nearly every Chinese person encountered New Year paintings in various forms. These artworks served diverse purposes: to express hopes for the future, to display the charm of beauty or playful children, to depict deities on doors inviting blessings, or to mark the passage of winter and the anticipation of spring. These vibrant creations, imbued with life’s passions, reflected a longing for prosperity, joy, and abundance, enhancing both the celebration of the New Year and the vibrancy of everyday life.

Born in the countryside and nurtured by local traditions, New Year paintings are candid and vivid, expressing a range of emotions — joy, anger, laughter, or teasing — with unrestrained freedom. For centuries, these colorful depictions have captivated the Chinese people, blending seamlessly with their ideals and emotional connections to life.

Today, although the festive atmosphere of the New Year has waned, many people still enjoy hanging decorative designs to brighten their lives during the season.

For Tianjin residents, the first choice for New Year paintings is naturally Yangliuqing woodblock prints. Those with time to spare often visit the ancient town of Yangliuqing to rediscover the vivid colors of the New Year.

Starting from the Sanchakou area and traveling about ten kilometers along the South Grand Canal, one arrives at Yangliuqing.

This ancient town, steeped in over a thousand years of Grand Canal history, exudes a timeless charm with its rich cultural heritage and quaint beauty. The streets are lined with painting studios and shops. Inside these stores, Yangliuqing woodblock New Year paintings come alive with their vivid hues, exquisite craftsmanship, and whimsical charm.

Beauty is a heartfelt transmission across the long river of time.

Yangliuqing woodblock prints are celebrated as the finest among China’s four major New Year painting traditions and were included in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage items in 2006. These artworks represent a “half-print, half-paint” technique that involves intricate processes: drafting, carving, printing, and hand-painting. For centuries, the people of Yangliuqing have conveyed life’s joys and desires through their unmatched patience and extraordinary skills.

These paintings reflect not only life’s pleasures but also its rich humanistic charm, love, and vitality. The repetitive cycles of crafting each painting instill a unique composure and dedication in the artisans, imbuing their work with a calm, refined spirit.

It’s no wonder that writer Feng Jicai called this place a “refined little town.”

On the northern bank of the South Grand Canal lie more than thirty ancient courtyard residences, arranged with a harmonious balance of density and space. Most of these courtyards were constructed during the Ming and Qing dynasties and the Republic of China era. Their architectural style is characterized by gray bricks, blue tiles, seamless masonry, round wooden beams and columns, as well as arched windows and doorways. These multi-tiered courtyards boast exquisite brick and stone carvings on gables, roof ridges, eaves, and gatehouses, showcasing an understated elegance and the legendary wealth of this small town.

The original owners of these grand residences were wealthy merchants who made their fortunes trading grain and salt along the canal. The prosperity brought by the canal allowed them to build luxurious homes and private gardens, living lives described as “adorned with flowers and fueled by burning oil” — an existence steeped in opulence.

The Shi Family Courtyard, once the residence of Shi Yuanshi, one of the “Eight Great Families” of late-Qing Tianjin, is hailed as the “First Residence in Northern China.” The Shi family hailed from Shandong Province and rose to prominence through the grain transportation business. They settled in Yangliuqing during the Qianlong reign of the Qing Dynasty, amassing vast landholdings that earned them the nickname “Shi with Ten Thousand Acres.”

The Shi Family Courtyard is a grand estate with three main sections and five sequential courtyards, constructed with overlapping beams and blue brick masonry. The residence includes living quarters, reception halls, courtyards, ancestral halls, and a theater, all arranged in an orderly fashion. Long corridors, pathways, and connecting gates create a seamless flow between spaces. The garden within features rock formations, flowing streams, lush greenery, and open water channels that evoke the natural world. Pavilions, gazebos, winding corridors, and arched bridges are artfully connected, creating a tranquil, pastoral retreat. One can imagine the scene during spring, with blossoms falling and gatherings in full swing — literary discussions, refreshments, and the enjoyment of music, chess, calligraphy, and painting. Such moments must have been truly delightful.

The theater in the Shi residence is the tallest structure on the estate. Combining architectural elements from both northern and southern styles, it is grand and intricate, with brick and wood carvings of exceptional craftsmanship. The theater accommodates 120 seats and would be lavishly decorated for festivals and banquets hosted by the Shi family. Esteemed Peking opera performers such as Sun Juxian, Yu Shuyan, and Tan Xinpei once graced its stage.

A small town like Yangliuqing, with such poetic charm and captivating allure, has produced countless legends and timeless stories — all thanks to the nourishing presence of the canal.

Water is the soul of Yangliuqing.

Situated west of Tianjin, Yangliuqing Town is bordered by the Ziya River and the Daqing River, with the Grand Canal meandering through its southern edge. The constant flow of water has endowed the town with a graceful and gentle temperament.

The “Triangular Marsh” water system is extensive, its fertile lands surrounded by reeds and lush vegetation. This environment was ideal for fishing, hunting, and farming. As the population grew, residents expanded their livelihoods to include fishing, gathering water chestnuts, cutting reeds for weaving, and planting fruit trees such as pears and jujubes. The robust wood of the wild pear tree, with its dense and fine fibers, proved ideal for making printing blocks. Its surface is smooth and durable, allowing carvers to work with precision. The resulting carvings produced clean and sharp lines that remained intact even after years of use, withstanding wear without losing detail. Over time, local artisans began to experiment with carving wild pear wood into printing blocks depicting door gods, the Kitchen God, Zhong Kui, Taoist sages, and moon palace scenes. These prints were sold during festivals to sustain their livelihoods.

In Tianjin, the “spirit horse” paintings are also called “paper horses.” They have unique regional names across China. In Neiqiu, Hebei, they are called “spiritual horses;” in Guangzhou, “noble figures;” in Beijing, a complete set is referred to as “baifen”; and in Yunnan, they are known as “armor horses,” “little horses,” or “paper fire”.

The origins of paper horses lie in ancient people’s profound desires — for blessings and protection from evil.

Throughout the year, with spring planting, summer cultivation, autumn harvests, and winter storage, agrarian societies labored tirelessly in the fields. For these farmers with kind-hearted dispositions, the cycles of the seasons, the shift between day and night, and the omens of fortune or calamity were shrouded in mystery. Sitting by the furrows, they gazed at the bright stars twinkling in the night sky but found no answers. Overawed by the forces of nature, they revered and feared them, seeking help from the divine.

By the Han Dynasty, people were hand-painting door gods like Shentu and Yulei, or Zhong Kui, the demon-slayer, to ward off evil spirits at the year’s end. Horses, being the fastest means of transportation in ancient times, were depicted as divine steeds, enabling gods to respond swiftly to people’s prayers.

With the advent of woodblock printing in the Tang and Song dynasties, these popular folk demands were met through the mass production of paper horses.

By the twelfth century, in large cities like Bianjing (Today’s Kaifeng in Henan), the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty, there were specialized shops selling paper horses. One of the most famous artworks from this period is Along the River During the Qingming Festival by Zhang Zeduan, a masterpiece that vividly portrays the bustling life of Bianjing, the largest city in the world at that time. The five-meter-long scroll features scenes of streets crisscrossing the city, tightly packed residences, and a myriad of shops and businesses — teahouses, wine establishments, and entertainment venues — with signs and banners filling the streets. Amid this lively setting, one shop sign prominently reads, “Wang’s Paper Horses.”

Another notable figure of the time, the writer Meng Yuanlao, documented the era in his book Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital. By the Northern Song Dynasty, paper horses had developed into a wide variety of styles and gained immense popularity.

The sophisticated Song literati indulged in the “Four Arts” (painting, calligraphy, music, and games like go). Paintings also became fashionable among urbanites and rural families alike. Bianjing boasted thriving art markets where vendors sold paintings to meet the growing demand. Folk artists would first create an original draft and then produce hundreds of copies through tracing for sale.

As demand outpaced supply, even hundreds of copies of a single design were insufficient. This unmet need coincided with the rise of woodblock printing, which allowed for the mass production of woodblock paper paintings. Some of these prints, with their auspicious themes of blessings and protection, became particularly popular during the winter solstice and the year-end festivals.

Sun Lei

Sun Lei is one of the top ten editors, reporters, and documentary directors of Tianjin Radio and Television Station.