植物病原菌孢子捕捉和监测—助力植物病害管理

摘要

农业生态系统中所有类型的植物均会受到病原菌的长期威胁。许多高风险植物病原菌能够通过空气传播, 甚至可随高空气流完成跨区域的远距离扩散。因此, 为了控制气传病害管理中的杀菌剂投入, 需密切监测空气中的病原菌孢子。病菌孢子捕捉技术作为监测空气中病菌孢子量的有效手段, 可为种植者或相关政府部门提供病害风险的早期预警信息, 辅助病害管理决策。近年来, 分子检测技术的发展拓宽了其在植物病害管理中的应用范围。本文主要从植物病害流行病学、病原体生物学、空气动力学等方面, 对病菌孢子捕捉技术, 以及利用该技术获得的数据改善病害管理策略的相关研究进展进行综述, 并讨论了应用病菌孢子捕捉和监测技术需要考虑的主要因素。随着物联网、大数据及人工智能等技术的不断发展, 该技术的发展面临着新的机遇和挑战。整合新技术和改善数据获取、分析、解释、共享效率, 实现病菌孢子捕捉的监测预警技术网格化、信息化与智能化的深度融合成为新的发展需求。

关键词

植物病害流行学;" 空气生物学;" 病菌孢子捕捉;" 植物病害监测预警;" 病害管理决策系统

中图分类号:

S 432.4

文献标识码:" A

DOI:" 10.16688/j.zwbh.2024437

收稿日期:" 20240823""" 修订日期:" 20240914

基金项目:

国家自然科学基金(32072359)

致" 谢:" 参加本试验部分工作的还有江代礼、谭翰杰、张能和纪烨斌等同学,特此一并致谢。

* 通信作者

E-mail:

刘伟wliusdau@163.com;周益林ylzhou@ippcaas.cn

#

为并列第一作者

Catching and monitoring airborne inoculum of plant pathogens: improving plant disease management

WANG Aolin1,2," FAN Jieru1," XU Fei3," CHEN Li4,nbsp; CAO Shiqin5," WANG Wanjun6,SUN Zhenyu5," LIU Wei1*," HU Xiaoping2," ZHOU Yilin1*

(1. State Key Laboratory for Biology of Plant Diseases and Insect Pests, Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese

Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing" 100193, China; 2. State Key Laboratory for Crop Stress Resistance

and High-Efficiency Production, College of Plant Protection, Northwest A amp; F University, Yangling" 712100,

China; 3. Institute of Plant Protection, Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Key Laboratory of Integrated

Pest Management on Crops in Southern Part of North China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs,

Zhengzhou" 450002, China; 4. College of Plant Protection, Anhui Agricultural University, Anhui

Province Key Laboratory of Integrated Pest Management on Crops, Hefei" 230036, China;

5. Institute of Plant Protection, Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou" 730070, China;

6. Tianshui Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Gansu Province, Tianshui" 741000, China)

Abstract

In agricultural ecosystems, plants of all types are under constant threat from various pathogens. Many high-risk plant pathogens are airborne and can be transmitted over very long distances across regions in a single step via high-altitude air currents. To minimize the use of fungicides for managing diseases spread by air, it is imperative to closely monitor airborne inoculum. Monitoring airborne inoculum provides an effective early warning system for growers and government agencies, offering valuable insights for disease risk assessment and management decisions. In recent years, advancements in molecular detection technologies have expanded the application of inoculum-monitoring data in plant disease management. This review summarizes recent progress in spore sampling technologies to improve disease management strategy, focusing on aspects of disease epidemiology, pathogen biology, and aerodynamics. We also address key main considerations for implementing airborne inoculum monitoring. With the rapid advancement of technologies such as the internet of Things, big data, and artificial intelligence, airborne inoculum monitoring is encountering new opportunities and challenges. Future research should focus on integrating these technologies to enhance data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and sharing. In other words, there is a growing need for inoculum-based monitoring and prediction technologies to achieve a deeper integration of surveillance networks, informatization, and intelligence.

Key words

plant disease epidemiology;" aerobiology;" spore trapping;" monitoring and prediction of plant diseases;" decision support systems in disease management

近年来, 农产品安全用药问题引起社会和公众的广泛关注[1]。然而在农业生态系统中, 植物病原菌几乎无处不在, 严重威胁植物健康[23]。为了控制植物病害管理中的杀菌剂投入, 需密切监测病菌繁殖体或传播体的数量或浓度[45]。许多高风险气传植物病原菌均以空气作为传播媒介[67], 其中, 真菌孢子更易于随气流传播[810]。因此, 捕捉和监测空气中的植物病原菌孢子, 特别是真菌孢子对于病害监测预警具有重要意义。

植物病原菌孢子的捕捉和监测研究可纳入一个特定的专业领域, 即空气生物学。Gregory是这一研究领域的先驱[11], 于20世纪30年代末期开始引领这一学科领域的研究和发展[12], 并在空气中病菌孢子检测工具的开发与应用[1314]、环境对病菌孢子传播的影响[15]、制定基于孢子量的病害流行风险指标[1617]等方面做出了巨大贡献。目前, 病菌孢子捕捉仍是监测空气中孢子量的有效手段。迄今为止, 研究者已开发出多种适于不同应用范围的取样装置或方法[18], 广泛用于大田作物[15, 1924]、经济作物[25]、果树[2628]和蔬菜[2930]上气传病原菌孢子的监测。特别是分子生物学技术的蓬勃发展, 为该领域的研究提供了先进的技术支持[17, 27, 3135]。

病菌孢子捕捉和监测作为病害管理的辅助决策工具, 需根据目标病害系统中特有的病原体生物学、病害流行学、病菌孢子在空气中传播的物理学特性等“量体裁衣”[36]。例如, 在病原菌越夏或越冬概率较高的场所定点监测有助于在病害流行早期发现病菌孢子;解析病菌孢子的扩散机制有助于推断病害的田间分布格局[37]。此外, 在复杂的农田环境中病菌孢子捕捉器的实际采样范围相对有限,还会受到孢子的捕获/沉积效率、作物冠层结构、采样器与菌源的相对位置、天气条件等因素的综合影响[7,17,3841],因此,制定一套合理的病菌孢子捕捉器布设方案和解读与挖掘获取的空气生物学数据将面临巨大挑战。

本文主要从植物病害流行学、病原体生物学、空气动力学等方面, 综述基于病菌孢子捕捉技术改善病害管理策略的相关研究进展, 具体内容涉及病菌孢子捕捉的研究目的、采样器的选用、采样器的数量和布设方案、空气生物学数据解读等。读者可根据自身的研究目的、目标植物病理系统、气候气象条件或局部小气候等, 在预算范围内选择相对最优的病菌孢子捕捉实施方案, 助力植物病害管理。

1" 空气中病菌孢子捕捉和监测的目的

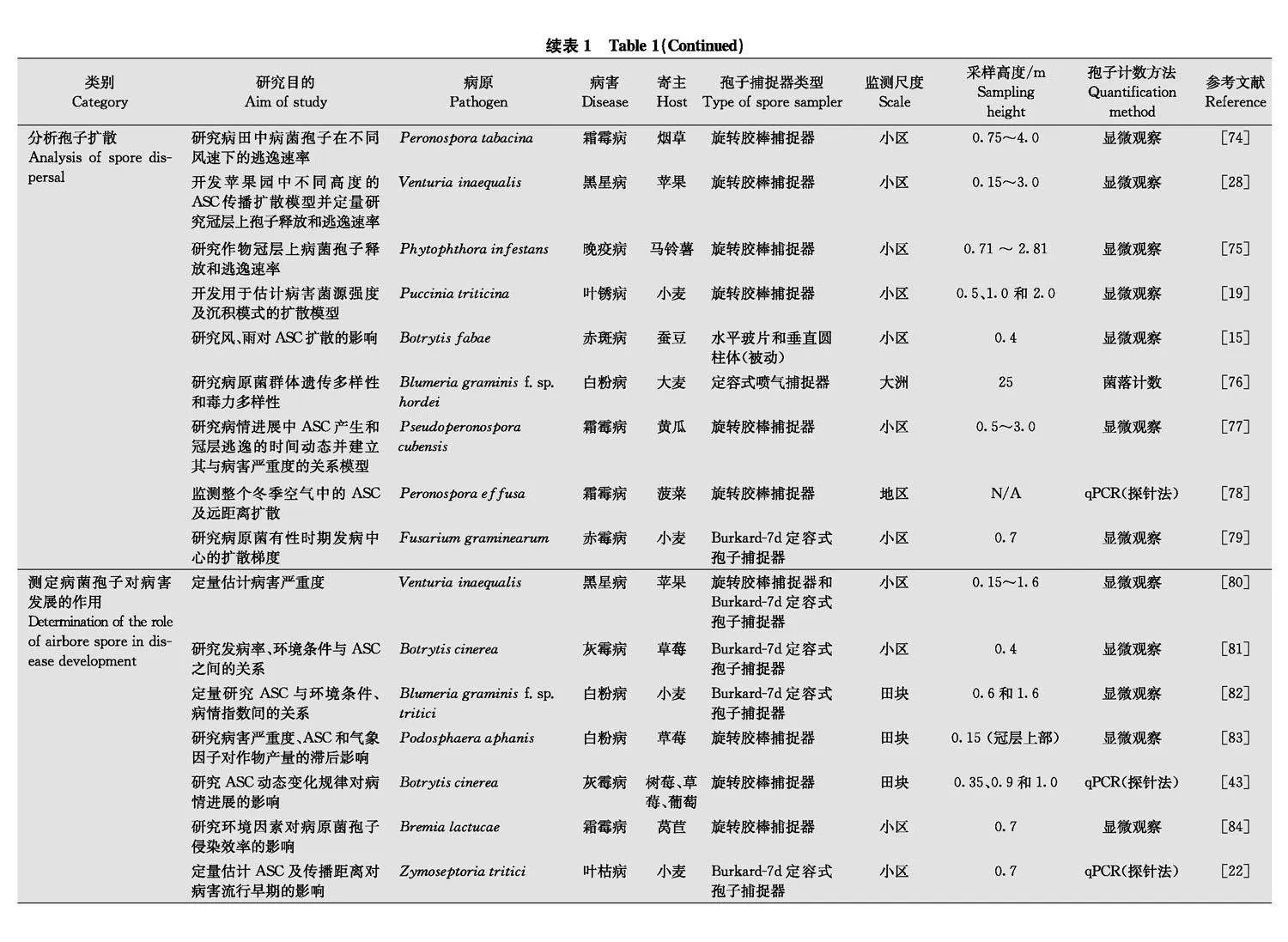

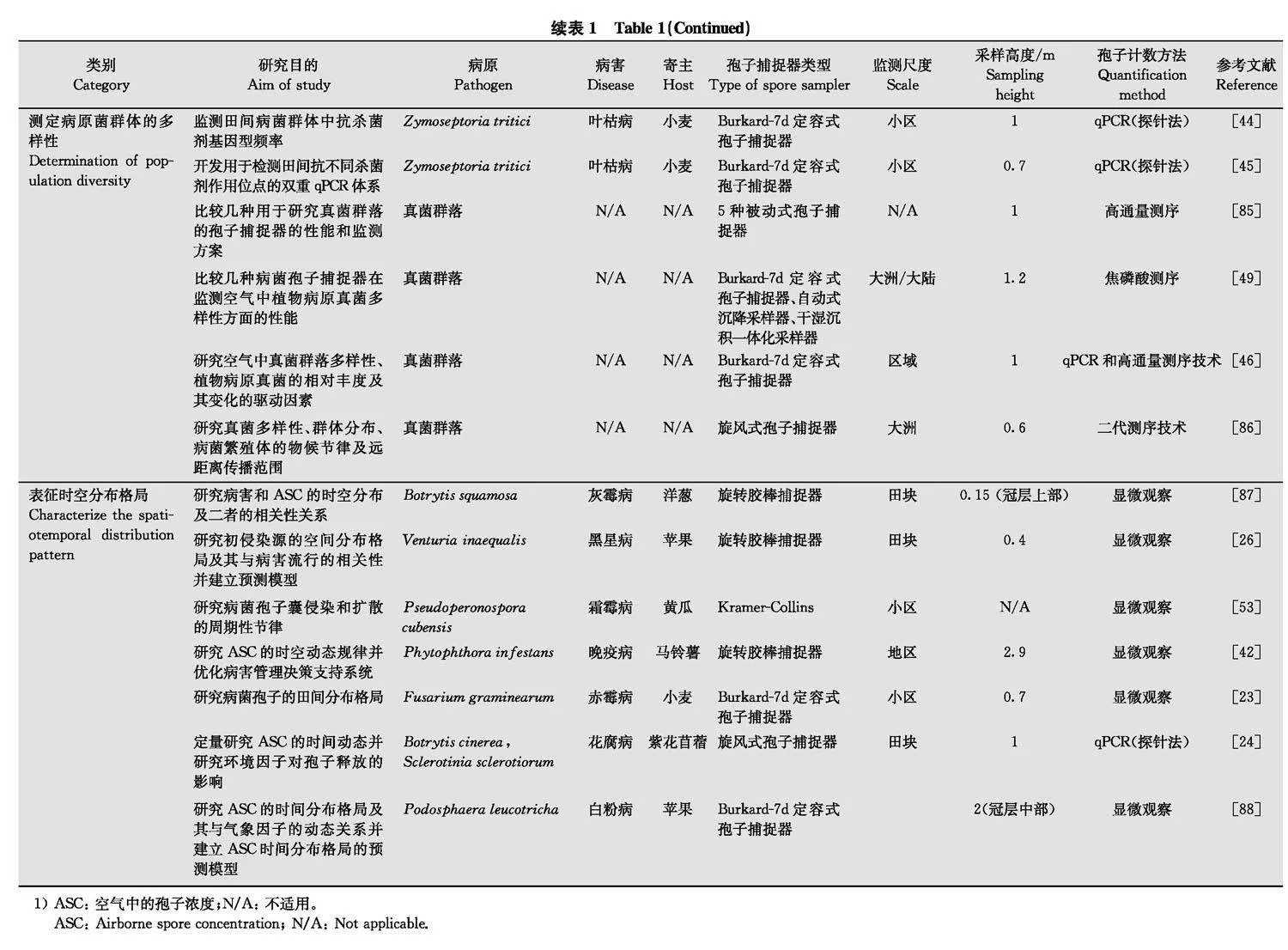

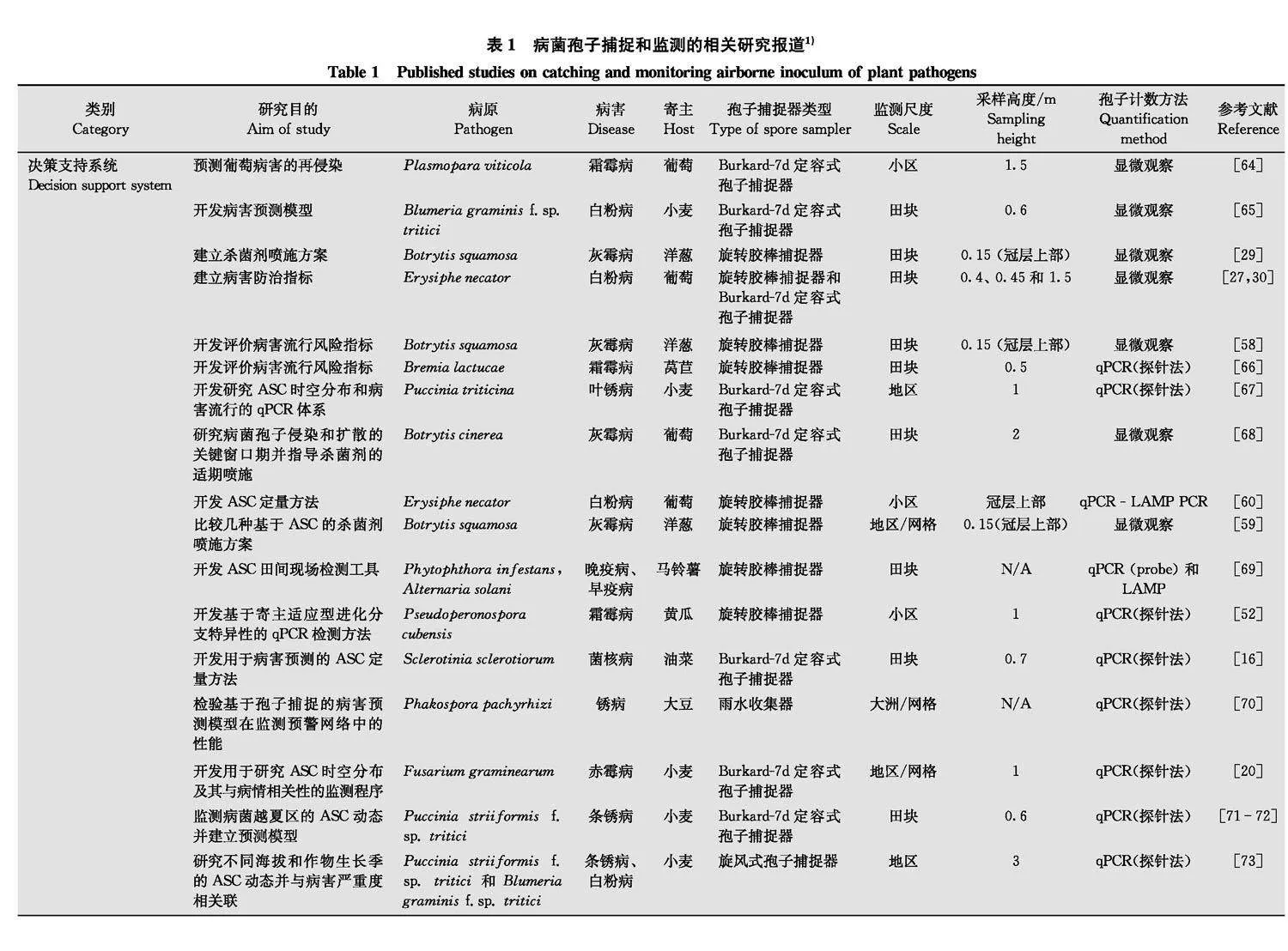

空气中病菌孢子捕捉和监测的主要目的是在不同时空尺度上了解气传病害流行动态和流行驱动因素的变化情况, 现已广泛应用于各类研究。根据空气中病菌孢子的捕捉和监测目的, 对代表性的应用型或基础型研究论文中涉及的病害、寄主及孢子捕捉器类型、研究范围或流行学尺度、采样高度以及病菌孢子量化方法等(表1)进行归纳。在应用研究领域, 病菌孢子捕捉数据可用于拟合组建病害管理决策系统[42], 还可根据病菌孢子的进展曲线, 结合气象条件、栽培管理、品种抗病性等研究病情的进展[43]。此外, 将病菌孢子捕捉与群体遗传学和分子生态学相结合, 还可研究抗药性或致病性相关基因型病原菌群体的结构与生态学特征[4446]。在基础研究领域, 该技术可用于研究空气中病菌孢子的传播规律或机制及时空变化动态, 为优化病害管理决策系统提供理论支撑。

近年来, 病菌孢子捕捉技术在植物生物安全风险监测和预警中也起到了举足轻重的作用[47]。我国于2021年4月15日正式实施《中华人民共和国生物安全法》, 其中第三章明确指出需要防范和科学应对植物有害生物威胁, 组织监测站点布局, 建设、完善监测信息报告系统, 开展主动监测和病原检测, 并纳入国家生物安全风险监测预警体系[48]。在植物生物安全风险监测预警体系下, 病菌孢子捕捉技术可用来衡量气候变化和农业生产系统对病原菌群体的影响, 或研究病原菌扩散、入侵、新致病力小种的产生、遗传多样性等[49]。

病菌孢子捕捉技术最大优势是其能在病害的视觉症状出现前确认空气中病菌孢子的存在, 适于马铃薯晚疫病菌Phytophthora infestans、苹果黑星病菌Venturia inaequalis、小麦印度腥黑穗病菌Tilletia indica、黄瓜霜霉病菌Pseudoperon ospora cubensis、小麦锈菌(条锈病菌: Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici, 叶锈病菌: P.triticina, 秆锈病菌: P.graminis f.sp. tritici)等具有远程传播能力的病菌[5057]。近年来, 为提升植物的防病减灾水平, 增强重大病情的监测预警和疫情防控处置能力, 病菌孢子捕捉技术融合了大量农艺资料和气象数据, 大大提高了风险预测精度, 并优化了管理措施[5859]。因此, 该技术还可作为改进现有预测预报系统的重要抓手, 为优化杀菌剂针对性喷施方案提供参考[26, 6063]。

2 "病菌孢子捕捉器的类型与适用范围

病菌孢子捕捉技术正逐渐发展成为许多农作物病害管理决策的重要辅助手段[27]。根据截获病菌孢子的空气动力学原理可将采样装置划分为重力沉降式、主动吸气式、撞击式和其他类型。不同类型的病菌孢子捕捉器在设计原理上存在差异且各有优缺点, 主要表现在捕捉效率、捕捉周期、样品处理难易、适用的靶标病菌孢子大小和监测频率等方面。因此, 具体的研究目的和适用范围也存在差异。

2.1" 重力沉降式采样装置

该装置工作原理简单, 空气中悬浮的病菌孢子在重力作用下会沉积在收集装置表面[89], 因而属于被动采样范畴。例如, 在垂直、水平或倾斜的支架上安装涂有硅脂或凡士林的载玻片。该装置突出优点是价格低廉, 并可在采样后将载玻片直接用于显微观察。然而, 由于整个孢子捕捉过程中采集的空气量是未知的, 无法计算空气中孢子的浓度(每m3空气中的孢子数)。此外, 该装置易受到空气中的大型生物或非生物碎屑影响而出现过饱和现象。不过, 由于其设计简单、便于操作且经济实用, 适于大面积监测或布设在复杂设备难以进入的区域, 同时也适用于预算有限或仅需检测目标孢子有无的研究。

2.2" 主动吸气型采样装置

定容式病菌孢子捕捉器是最为常见的主动吸气型采样装置,

其中又以Burkard-7d定容式病菌孢子捕捉器(http:∥www.burkard.co.uk/7dayst.htm)最为典型。该类型采样装置

通常使用电源驱动的转子或吸气泵收集空气中的病菌孢子, 吸入的孢子在惯性的作用下被黏性表面(如胶带)截获[90]。采样表面逐小时转动, 不易饱和, 因此可对空气中的病菌孢子进行连续捕捉。该装置的突出优点是吸气流速可控, 且在整个采样期间保持恒定, 可对吸入的空气进行量化, 进而计算每小时每立方米空气中的孢子数量。风对定容式孢子捕捉器的捕捉效率影响相对较小, 但受限于采样表面截获孢子时的成功率。一些轻量的孢子被吸入后可能会绕开采样表面, 被捕捉器内壁截获;而质量较大的孢子, 当撞击采样表面产生的瞬时动能超过引力势能时, 孢子则会反弹,以上2种情况发生时均无法成功截获孢子[91]。

液体撞击滤尘器和串联式粒子碰撞捕捉器也是主动吸气型采样装置[89], 吸入的病菌孢子通过培养基保持活性。该装置能够靶向目标病原菌, 尤其适合较小的病菌孢子或细菌, 如梨火疫病菌Erwinia amylovora。由于细菌在静风(水平风速为0~0.2 m/s)中沉降速率极小(≈0.01 cm/s), 理论上无论环境中风速如何变化, 捕捉效率都无限接近1[91]。但细菌在空气中的传播机制目前尚未明确: Prussin等[92]和 Gilet等[93]认为, 细菌在降水时通过风雨传播;但Lindemann等[94]研究发现, 晴朗干燥的天气条件下, 空气中仍能够捕获高浓度的细菌;Morris等[9596]研究证实, 细菌也可将锈菌的夏孢子作为其在空气中传播的载体。因此, 监测空气中细菌浓度时应格外谨慎,且还需要更多的基础研究为其提供理论支撑。

2.3" 撞击式采样装置

旋转胶棒式病菌孢子捕捉器(Rotorod)是最典型的撞击式采样装置, 优点是在田间条件下, 捕捉表面相对于环境风速具有更高的线性速度(亦称切向速度), 能极大降低风速变化对捕捉效率的影响。

Rotorod式孢子捕捉器的理论捕捉效率与目标孢子的形态和密度有关。在田间应用中, 实际捕捉效率大多低于理论值[9798]。主要存在三点原因: 1)Rotorod探头会干扰周围气流;2)旋转臂周围存在大量的湍流和涡旋;3)撞击旋转臂的孢子由于黏性不足或采样表面过饱和未被全部截获,

实际应用中,研究人员可在装置运行前进行质控检查, 例如: 确保旋转臂具有足够强度的黏性;确保黏性涂层均匀且厚度适中(以靶标病菌孢子的半径长度为宜),从而降低由采样面黏性不足引起的截获误差。

在降水期间, 为避免Rotorod捕捉器的采样面被雨水浸湿, 需要设计恰当的挡雨板[13]。研究人员可根据孢子捕捉周期内雨滴的终速度(取决于雨滴的大小及分布)和风速预报, 针对性的设计和改进挡雨板的尺寸和安装位置。

2.4" 其他采样装置

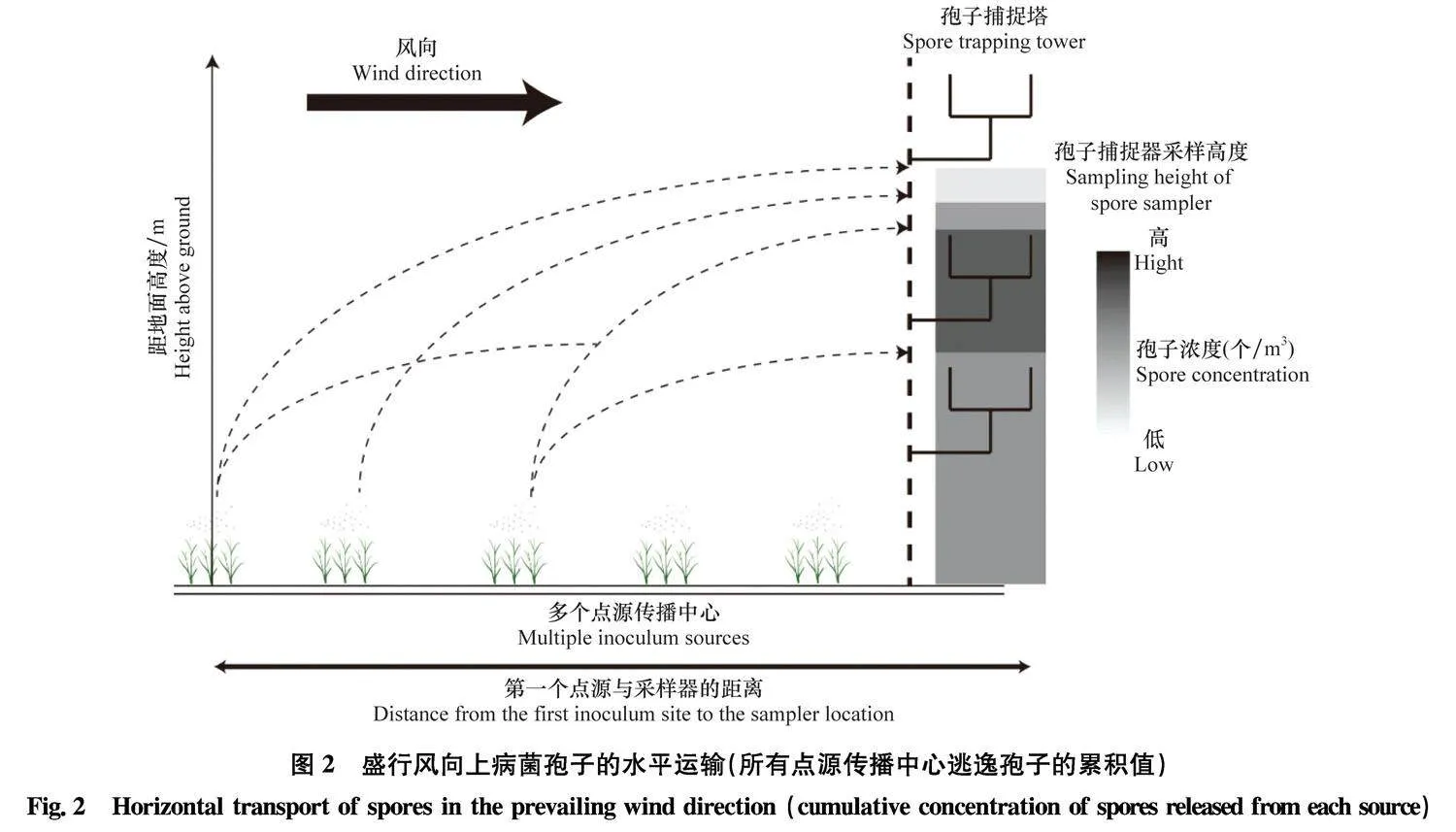

漏斗式采样器由顶部与地面垂直的漏斗, 漏斗底部的过滤网和离心管组成。过滤网可阻隔随雨水沉积的大型植物组织残体、昆虫和杂质等, 含有病菌孢子的雨水则收集在下部的离心管内(图1c)。该装置适于收集长距离传播并在降水时沉积的病菌孢子, 例如大豆锈病菌Phakopsora pachyrhizi孢子[70], 或通过雨水飞溅传播的病菌孢子, 如小麦赤霉病菌Fusarium graminearum species complex孢子[99]或苹果炭疽病菌Colletotrichum fioriniae孢子[100]。该装置还可通过安装雨量计来量化单位体积降水中的病菌孢子数量, 但管内雨水蒸发或超过离心管容载量时可能存在量化误差。

另一类漏斗式采样器其上部是平行于地面的球状或圆柱状“漏斗”, 漏斗末端与尾翼(或副翼)相连, 使其始终迎风, 病菌孢子则收集在漏斗底部的过滤器中(图1a,b)。这种采样器的优点是价格便宜, 可在田间大规模布设, 但很难提供病菌孢子浓度数据。然而, 当二进制的病菌孢子数据(存在/不存在)可满足研究需求时,该装置特别适用于大尺度的流行病学监测。该装置目前已成功用于美国佛罗里达至加拿大的整个北美地区大豆锈病菌Phakopsora pachyrhizi[101]和安大略地区马铃薯晚疫病菌Phytophthora infestans的流行动态监测(Sporometrics公司, 加拿大)。

总之, 旋转胶棒式病菌孢子捕捉器和Burkard-7d定容式病菌孢子捕捉器更适于监测大小在10 μm以上的真菌和卵菌孢子, 是农业中最常用的病菌孢子捕捉装置[20,24,2930,5859,78,8384,87,102]。液体撞击滤尘器和串联式粒子碰撞捕捉器则更适于捕捉较小的病菌孢子或细菌。

3" 病菌孢子捕捉器的布设

地面布设的病菌孢子捕捉器从水平和垂直距离上都应尽可能靠近菌源[103],如布设在病菌更可能安全越冬的场所。但基于病菌孢子捕捉的空气生物学数据通常具有高度的不稳定性,受风速、风向、目标病害系统和当地条件等与病菌繁殖体相关的农业生态小气候的影响[104]。在对菌源空间分布或规模缺乏足够了解的前提下,病菌孢子捕捉器的初始布设往往会代入研究人员的主观性。通常在获得首批试验数据后,才能有针对性的调整布设方案,并随着数据和经验的累积,不断优化和完善。因此,围绕有关病菌孢子捕捉器布设的关键问题展开讨论,如:病菌孢子捕捉器地面布设的具体位置、捕捉范围、捕捉器的数量、空气生物学数据的解读等,并简要介绍移动机载采样平台。

3.1" 哨兵样地: 在一个田块或区域侦查首个病菌孢子迁入事件

理想情况下,应在本地初侵染发生前探测到迁入的病菌孢子。但在干燥少雨的天气条件下, 随高空气流远距离传播的病菌孢子难以仅通过干沉降作用(干沉降是指生物气溶胶如病菌孢子直接沉降到地表的现象)到达地面和寄主植物[105]。因此,传统病菌孢子捕捉技术发现的首个孢子通常来源于附近的本地菌源而非远距离迁入的异地菌源。

病菌孢子捕捉和在哨兵样地中进行病害侦查是识别首波孢子迁入的2个基本途径。种有易感作物的小块哨兵样地中的采样速率可能比任何病菌孢子捕捉器都高,采样速率Dr=vgfsEiAc,其中,Dr(m3/s)表示每Ac(m2)面积哨点作物的采样速率,vg(m/s)表示孢子沉降速率,fs和Ei分别表示孢子存活率和孢子在作物上的侵染成功率。理想条件下(fsEi=1)对于常见的孢子(Dr≈0.02Ac),面积为3 m×3 m的哨兵样地上的采样速率可达10 800 L/min,远高于Burkard-7d和Rotorod捕捉器的10 L/min和40 L/min,但该法受限于病菌侵染率及病害症状是否肉眼可见和易于识别[70]。此外,对于潜伏侵染时间较长的病害,病菌孢子捕捉更具优势。

3.2" 采样频率/持续时间

空气中的病菌孢子具有一定的周期性变化规律。Aylor等[75]研究发现,空气中马铃薯晚疫病菌孢子在1 d内表现出显著的逐小时变化。并且,绝大多数病菌孢子的产孢和释放都存在一定的昼夜节律,通常在夜间产孢,白天释放。因此,采样周期、频率和持续时间大多以此作为依据。研究发现,通常中午前后病菌孢子释放量最高,其中链格孢属Alternaria spp.、枝孢属Cladosporium spp.、黑粉菌属Ustilago spp.和白粉菌属Erysiphe spp.的病菌孢子在13:00左右达到峰值[106]。但不同病菌存在一定差异。中国农业科学院植物保护研究所小麦白粉病研究组此前在对田间小麦白粉病菌分生孢子浓度动态的监测研究中发现,白天捕获的孢子浓度高于夜间且通常在正午达到峰值[82];最近一项关于田间小麦条锈病和白粉病混合发生条件下空气中2种病菌孢子浓度动态变化的研究表明,条锈病菌夏孢子和白粉病菌分生孢子的释放峰值均在10:00-14:00(数据未发表)。相反,禾谷镰孢Fusarium graminearum子囊孢子的释放峰值通常出现在午夜[40,92,107108],而其大型分生孢子的释放时间在1 d中呈均匀分布,不表现明显的昼夜节律[107]。

根据病菌孢子释放的昼夜节律,可将病菌孢子释放周期(孢子浓度峰出现概率较高的时间段)作为设计采样周期的参考依据,并根据环境、寄主和病菌孢子的类型适当调整。有研究指出,根据病菌孢子释放周期延长采样时间,并在此期间进行分段采样,能够使数据更具代表性。例如,洋葱灰霉病菌Botrytis squamosa最初在10:00-12:00进行固定2 h的孢子捕捉[2930,5859,87]。但后续研究表明,在08:00-14:00间进行分段采样(旋转胶棒式捕捉器,开机10 min和关机10 min连续自动切换,实际采样时间占50%),数据收集更具代表性[109];而莴苣霜霉病菌Bremia lactucae孢子可在06:00-15:00之间进行分段采样(实际采样时间占50%)[84]。

旋转胶棒或玻片式采样装置因采样表面容载能力有限,更适于在病菌孢子释放周期内进行分段采样。并且,采样周期、频率和持续时间还应考虑采样面的饱和速率。Burkard-7d定容式孢子捕捉器由于能够连续运行且采样表面不易饱和,通常无需分段采样。

3.3" 采样高度

地面布设的病菌孢子捕捉器放置高度一定程度上取决于研究目的(表1)。理想条件下, 应考虑架设病菌孢子捕捉塔, 以便在不同高度进行采样[91]。但受限于场地和设备, 生产上难以大规模推广使用病菌孢子捕捉塔。公认的经验是当监测本地或局部菌源时, 将病菌孢子捕捉器布设在作物冠层上方;当监测异地或远距离迁入的菌源时, 布设在高于地面几米的位置。

研究人员通过测定病菌孢子的垂直扩散梯度和估计冠层释放的病菌孢子比例, 发现不同采样高度上的病菌孢子浓度测量值存在显著性差异且随高度的增加而下降, 例如烟草霜霉病菌Peronospora tabacina[74]、苹果黑星病菌Venturia inaequalis[28]和马铃薯晚疫病菌Phytophthora infestans[75]。特别是对于植被覆盖率较低的作物, 由田间点源释放的病菌孢子随高度的增加浓度会迅速衰减, 距地3 m以上的空气中通常难以捕获病菌孢子。中国农业科学院植物保护研究所小麦白粉病研究组此前关于不同采样高度上小麦白粉病菌孢子浓度差异的研究也表明, 1.6 m高度处(冠层外)的孢子浓度显著低于0.6 m(冠层内)[82]。

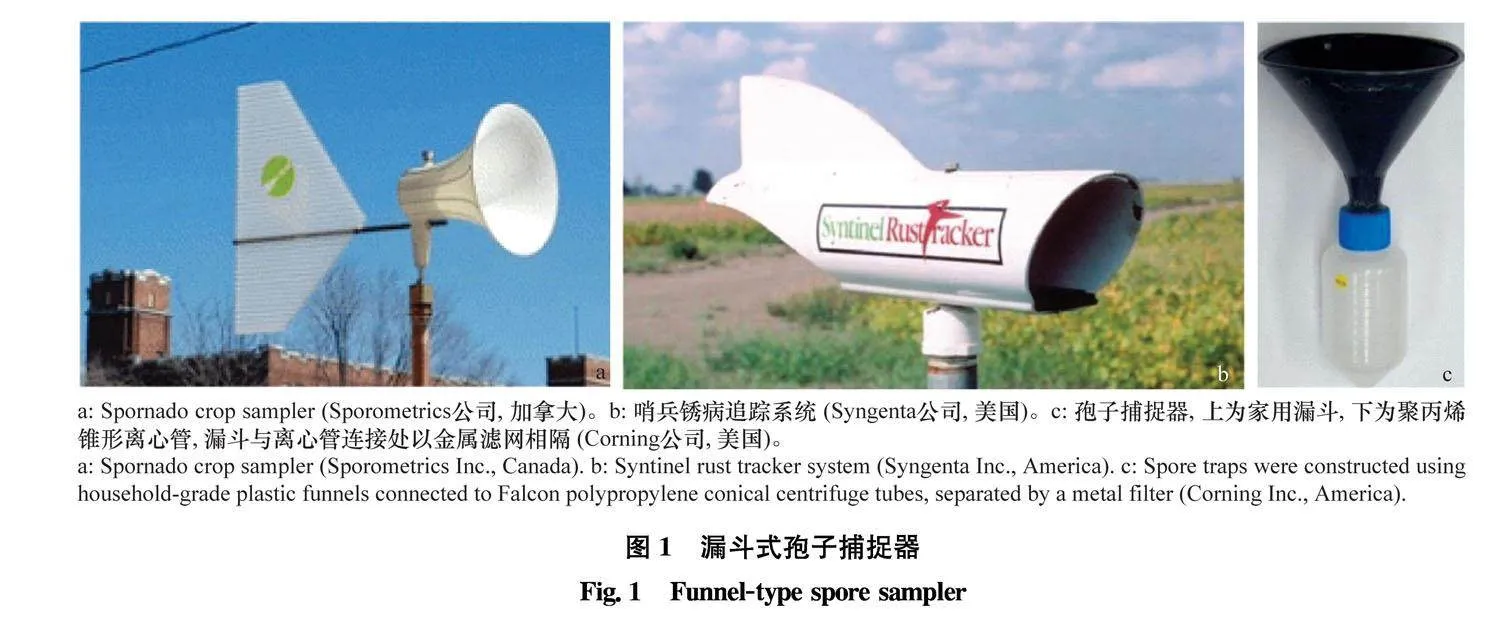

对于单点源的传播中心,冠层逃逸的病菌孢子受羽流影响浓度会迅速衰减,因此,病菌孢子在垂直和水平方向上的捕捉概率会随菌源与采样器间距离的增加而降低[110]。但田间环境下可能存在多个点源传播中心,由每个点源传播中心成功逃逸的病菌孢子会随盛行风单独或合并到达各个采样高度,从而使得捕获到的病菌孢子实质上可能来自多个点源传播中心,导致病菌孢子浓度数据与采样高度之间并非简单的线性负相关,还会受第一个点源传播中心与采样器之间距离及其余点源数量的复合影响(图2)[91]。因此,研究人员还可根据盛行风风向上菌源位置和数量等信息,进一步优化病菌孢子捕捉器的布设方案[19,28]。

前人基于长期对空气中各种病菌孢子垂直分布格局的观测经验, 总结归纳出适于捕捉不同病菌孢子的采样器布设高度。针对本地菌源, 如监测洋葱灰霉病菌Botrytis squamosa孢子时, 在生长季早期通常将采样器放置在距地1 m处, 并根据作物的生长情况适时调整[5859, 109];监测菠菜、莴苣霜霉病菌Bremia lactucae孢子时, 采样器则通常布设在距地0.53 m处[33,78,111];当研究小麦冠层上方禾谷镰孢菌F.graminearum孢子时空动态与赤霉病严重度及DON毒素(deoxynivalenol, 脱氧雪腐镰刀菌烯醇)关系时, 采样器放置在距地1 m高度[20], 该布设高度同时也适于监测葡萄白粉病菌Erysiphe necator和草莓灰霉病菌Botrytis cinerea孢子[27, 43, 103]。中国农业科学院植物保护研究所小麦白粉病研究组多年来连续进行了小麦白粉病、条锈病和赤霉病春季流行期田间病菌孢子的时空动态监测, 发现将Burkard-7d定容式孢子捕捉器布设在小麦冠层高度(0.6~1 m)更能代表一个地块的本地菌源[35, 65, 82, 112114]。监测远距离迁入的异地菌源时, 如Fall等研究马铃薯晚疫病菌孢子的区域扩散模式时, 将病菌孢子捕捉器放置在距地2.9 m高度以收集大部分由远距离迁入的病菌孢子[42]。

3.4" 病菌孢子浓度空间分布格局及扩散梯度

不同病菌孢子传播的空间范围存在一定差异,有的病菌孢子主要在相邻的寄主间短距离传播,有的则可跨不同地块远距离传播,甚至跨区域扩散。因此了解空气中目标病菌孢子浓度的空间分布格局、扩散性质或范围,亦可为病菌孢子捕捉器的布设提供建设性指导。在农业生态系统中,病害田间分布型(分布格局)主要有3种,即均匀分布(正二项分布)、随机分布(泊松分布)和聚集分布(奈曼分布或负二项分布)[37],病菌孢子的截获概率受其影响。例如,当不考虑孢子捕捉器在田间具体位置时,完全随机分布型病害较聚集分布更有可能截获病菌孢子[115116]。相反,当病害呈聚集分布格局且孢子捕捉器放置位置恰能截获菌源中心释放的孢子羽流,则发现早期扩散的病菌孢子的概率更大[115,117]。

目前, 已有研究报道了空气中病菌孢子的空间分布格局。在田间或小区尺度上, Charest等[26]研究发现, 空气中苹果黑星病菌Venturia inaequalis子囊孢子的空间分布格局呈负二项分布的聚集分布模式;类似地, 在葡萄园和洋葱田中捕获的具有杀菌剂抗药基因型的Botrytis cinerea和B.squamosa孢子同样具有聚集分布模式[102]。但病菌孢子浓度的空间分布格局也随病情进展和病害严重度的增加而改变。Carisse等[87]发现, 在病害流行早期且病菌孢子浓度较低时, 空气中的B.squamosa孢子呈随机分布, 而在后期病菌孢子浓度升高时呈聚集分布。在区域尺度上, Fall等[42]研究发现, 马铃薯晚疫病菌孢子呈负二项聚集分布格局, 且空间异质性随病菌孢子浓度的增加而增加。因此, 当病菌孢子浓度呈聚集分布时, 为了提高数据的代表性,需尽可能增设更多的病菌孢子捕捉器, 且数量随孢子浓度空间异质性的增加而增加;反之, 当病菌孢子浓度呈均匀分布时, 布设1台就可满足同等监测需求[118]。

不同病菌孢子的扩散梯度存在明显差异。其中短距离传播的如小麦赤霉病菌Fusarium graminearum, 其子囊孢子和大型分生孢子浓度在距菌源中心5~22 m和5 m处降至10%[23, 79];香蕉黑叶条斑病菌Mycosphaerella fijiensis的子囊孢子仅在菌源中心附近几米内有效传播, 而其分生孢子则很少扩散[119]。具有远程传播能力的病菌孢子如马铃薯晚疫病、小麦锈病(包括条锈、叶锈和秆锈)、小麦白粉病、大豆锈病等的病菌孢子可扩散至几百米, 甚至能跨越高山、河流、海洋或大洲, 一次性传播几千公里[110]。因此, 对于短距离传播的病菌孢子, 一般在病害流行的田间尺度上监测本地菌源, 病菌孢子捕捉器的位置应尽可能靠近病菌的越冬或越夏场所;而对于远距离传播的病菌孢子, 除了监测本地菌源外, 还需及时发现异地菌源的迁入, 在区域尺度上实施病菌孢子捕捉网格化管理。

病菌孢子的释放机制大体可分为主动和被动两类:主动释放的孢子如子囊孢子,子囊壳遇水吸湿后会形成膨压,当静水压力足够大时,子囊孢子受力排出并向上弹射一段距离,释放到一定高度后在风的辅助下完成后续传播和扩散;而被动释放的孢子如分生孢子或夏孢子则需在湍流和阵风中释放,且风速需达到一定的临界值[91]。主动释放的病菌孢子其释放高度受孢子形状、大小、质量、状态(泡水或暴露在空气中)、相对湿度变化等因素的影响[7475,120];而被动释放的病菌孢子必须在风的作用下摆脱气动阻力,使其脱离产孢器官和突破寄主叶片表面的黏性边界层时才能有效释放[121123]。此外,主动释放的病菌孢子通常附着于土壤或秸秆残茬;而被动释放的病菌孢子一般寄生在叶片表面,释放高度取决于发病部位。因此,病菌孢子的释放机制也是孢子捕捉器布设前需考虑的重要因素之一。

3.5" 病菌孢子捕捉数据的代表性

病菌孢子捕捉器的采样范围受地形、物理屏障、尤其是作物冠层几何结构(高度、密度)等因素的影响,导致在实际应用中仅利用单个采样器获取空气生物学数据来预测病害的发生和流行面临一定的挑战[67]。

采样覆盖范围(数据代表性)是指在一定概率阈值下截获病菌孢子时的菌源分布范围[111,124],其在不同程度上受到冠层结构的影响。根据气流和病菌孢子的扩散机制,作物冠层结构可分为两大类(图3a):“行结构作物冠层”(例如,棚架作物、多年生作物和蔬菜作物)和“单株作物冠层”(例如,传统果园)[36]。

玉米、大豆和小麦等粮油作物虽成行种植,但行距相对于冠层高度可忽略不计,冠层彼此相连且在空间上均匀致密。因此不受“行结构”对流体运动的影响。对于这类高1.5 m左右的作物冠层,3D高斯羽流模型适于模拟病菌孢子的田间扩散行为,且羽流形状不受风向的影响[41],病菌孢子捕捉器5 m范围内的采样概率较高。

传统果园(如核果类果园)植株间等距, 当风向偏离种植行时, 气团在植株间穿梭形成的尾流会使其随后的运动轨迹明显偏离平均风向(图3b)。此外, 气团在经过冠层时会受到合力向上的空气阻力, 而冠层以下气团在运输过程中则明显减速和稀释[125]。因此, 放置在冠层顶部的采样器截获病菌孢子的概率较高(图3b), 且捕获到的病菌孢子最有可能来自病株冠层的上1/3处[51, 126]。但无论风向如何变化, 均很难截获采样器周围10 m范围外的病菌孢子, 通常15 m已达有效捕获的临界距离。

“行结构作物冠层”(如葡萄园)通常在种植行上植被覆盖较为密集,而行间大多为裸露的空地, 导致气团在流动过程中形成周期性循环模式: 病菌孢子由靠近“行”一侧的冠层底部扩散到冠层顶部, 再由另一侧的冠层顶部扩散到冠层底部, 如此往复[127128]。风向和风速均影响“行结构作物冠层”中病菌孢子羽流的形状, 从而影响采样覆盖范围[129]。当风偏离种植行的方向时, 气流在“行”的引导下向靠近“行”一侧偏转, 孢子羽流向“行”所在方向倾斜,使得病菌孢子主要来源为采样器周围的2~3行的患病寄主作物, 并且有机会截获较远距离上的病菌孢子(图3b);当风向与“行”平行时, 病菌孢子羽流形状会明显收缩, 病菌孢子捕捉数据仅能代表采样器所在“行”[3939, 130]。此外, 布设在种植行内部的采样器由于附近空域被植被填充, 病菌孢子会因叶片的拦截效应逐渐稀释或提前沉降, 采样覆盖范围通常低于布设在行间通道上的情况。

综上,如小麦、玉米、大豆这类冠层致密的作物,采样覆盖范围的形状或大小仅受风速影响,对采样器的位置或风向较不敏感(图3b);而高敏感冠层,采样器的位置、风向、作物类型均是采样覆盖范围的潜在影响因素(图3b)。因此,采样器的布设应在尽可能提高发现病菌孢子概率的前提下考虑数据的可读性和解释性。例如,当葡萄园中的盛行风偏离葡萄藤方向时,研究人员应意识到采样器倾向于截获其所在“行”上患病寄主的病菌孢子,并且这种“偏好”随行间距的增大而增大,而果园管理者则无需过多关注这个变量。

3.6" 病菌孢子捕捉网格化布局

病菌孢子捕捉网格化布局是为了同时在较小尺度下监测本地菌源和在较大尺度下监测跨区域迁移的菌源。其中,应用最为广泛的是监测大豆锈病菌Phakospora pachyrhizi孢子在美国和加拿大之间南北扩散的病菌孢子捕捉网格。该网络覆盖北美26个(省)州的约15 000个监测点,基于统一标准的程序处理和分析样品,并结合计算机建模模拟大豆锈病的进展情况,最后通过ipmPIPE信息平台(https:∥www.ipmpipe.org)实时发布病害扩散风险及具体的杀菌剂施用指南[70]。在比利时布设的病菌孢子捕捉监测网格,通过监测瓦垄大区(自治行政区)空气中的小麦条锈病菌Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici孢子,预测当地小麦条锈病的进展情况[131]。在澳大利亚,由固定位置的气旋式孢子捕捉器和安装在车顶的移动式孢子捕捉器(车载RAM空气取样器)共同构成病菌孢子捕捉网格,用于长期监测空气中的小麦褐斑病菌Pyrenophora tritici-repentis和油菜黑胫病菌Leptosphaeria maculans的孢子,近年来也将危害经济作物的病原菌列为监测对象[132]。

与上述在较大空间尺度(gt;100 km)上布设的病菌孢子捕捉网格不同,加拿大魁北克省的病菌孢子捕捉网格旨在监测30 km×30 km的区域[59]。病菌孢子捕捉结果和模型预测的病害流行风险能够实时反馈给生产者,显著降低了杀菌剂的使用剂量和频率,提高了环境、生态和人类健康效益[109]。

理想情况下,病菌孢子捕捉网格覆盖下的每一个地块都应布设至少一台病菌孢子捕捉器,但人力或物力通常无法保障如此高负荷的监测网格运转。因此,病菌孢子捕捉网格化布局可基于传统的病害勘察和长期定点监测,并融合多种数据类型,以增强重大病情监测预警和防控处置能力[59]。

3.7" 移动机载采样平台

小型载人飞机是最早用于研究高空大气中病菌孢子的移动采样平台,为病菌孢子的远距离传播提供了有力佐证[50,133]。近年来,随着无人/遥控驾驶飞行器的发展, 成功验证了距地300 m以内空域水平运输达1 km的病菌孢子扩散模型, 其性能远超地面布设的孢子捕捉器, 同时也弥补了距地10~300 m之间空域的研究空白(载人飞行器在低于300 m的飞行高度上受限)[80, 134136]。

在较大尺度的田间病菌孢子监测方面(扩散距离超过100 m且距地超过50 m), 移动机载采样平台具有一定的优势: 1)采样覆盖范围更大;2)可根据风向随时调整飞行轨迹;3)采样效率高, 能够发现较低浓度下的病菌孢子。但也受限于无人机的续航和任务载荷能力, 并且在对近地面空气进行采样时可能受到大气湍流的干扰, 使飞行安全受到影响[137]。“多旋翼”无人机虽然能够克服复杂的湍流活动, 但旋翼转动形成的下洗气流也会对正常采样造成一定影响, 并且在悬停时采样效率会大幅下降[91]。

由于飞行成本的限制,长期以来很难通过移动机载采样平台获得连续且长数据链的病菌孢子浓度的时间序列[138]。Gottwald等[139]首创性地在无人机上搭载伺服系统控制的采样装置(“鼓”),通过滑动“鼓”的位置(包含20个连续的采样位置)能够在预设时长下实现不同高度和区域上的连续采样。Gonzalez等[140]在此基础上参考Burkard-7d定容式孢子捕捉器的设计原理(http:∥www.burkard.co.uk/7dayst.htm),设计了一款适合小型或中型无人机搭载的简易轻量型采样装置,在高空采样时不受飞行速度和周围气流的影响。未来,研制和改良适合小型无人机搭载的轻量、低耗、高效且能连续工作的采样器有望进一步扩大移动机载采样平台的应用范围,并且对整个空气生物学领域的研究也将是划时代意义的重大变革,正如20世纪50年代Burkard定容式孢子捕捉器的问世[90]。

地面固定位置上布设的病菌孢子捕捉器采样方案的制订需充分考虑风速、风向、特定病害系统、冠层结构等不确定性因素的影响。因此,需要与流体力学、物理学、气象学、计算机科学、植物生理学等进行广泛深入的学科交叉。病菌孢子捕捉器一旦布设,其所在位置和环境条件将作为解读采样数据合理性和代表性的依据,可为具体的病害综合防治提供指导。最后,随着无人机技术的迭代发展,更多移动机载采样平台有望应用于病菌孢子捕捉研究,弥补地面布设的采样器机动性不足的短板。

4" 基于病菌孢子捕捉数据设定防治指标

预测病害的流行风险对制定有效的病害综合治理策略至关重要[141]。在病害综合治理系统中,常通过防治指标或称经济阈值确定是否必须启动防治方案及采取行动的最佳时机和手段。由于病菌孢子浓度与病情进展密切相关,因此可基于病菌孢子捕捉技术预测病害的流行风险,间接估计作物产量或品质的损失情况,从而指导具体的防治决策[27,58,83]。

Carisse等[29]将空气中洋葱灰霉病菌Botrytis squamosa孢子浓度达10~15个/m3作为杀菌剂喷施的行动阈值, 降低了56%~75%的杀菌剂有效用量。Van der Heyden等[59] 将“检出第一个病菌孢子”作为防治指标, 并将病菌孢子浓度达到10个/m3及产孢潜力指数[142]超过80作为再次启动杀菌剂喷施计划的行动阈值。Thiessen等[103]也将检出首个病菌孢子作为防治指标, 减少了杀菌剂喷施次数。但空气中的病菌孢子对病害发生和流行的驱动作用还受作物种类、抗病性、生育期、气象条件等因素影响。Carisse等[58]认为病菌孢子捕捉需结合天气预报, 联合开发病害流行风险的预测指标, 以指导精准防控。

不同病原菌的生存策略不同, 有些病菌单个孢子的侵染能力有限, 但可产生巨大的病菌孢子群体。因此,基于病菌孢子捕捉技术制定的防治指标相对较高, 如监测麦类作物、草莓、葡萄上的白粉病菌或麦类作物上的锈菌孢子等。相反, 十字花科、黄瓜、葡萄等作物上的霜霉病菌, 虽然产孢量有限, 但单个孢子的侵染力较强,故相应的防治阈值应适当降低[47]。此外, 同种病原菌在不同作物或同种病原菌的不同株系在同一作物上侵染和产孢能力的差异也影响防治指标的制定。Carisse等[43]发现, 覆盆子和草莓上的灰霉病菌Botrytis cinerea孢子浓度增长速率较葡萄更快。Fall[143]比较了马铃薯晚疫病菌不同无性系之间的侵染能力, 发现造成同等严重度时, 不同无性系的孢子浓度存在显著性差异。

近年来, 基因组学及测序技术的发展为流行病学上存在显著差异、寄主特异、或杀菌剂抗药性基因型的病菌孢子的监测提供了理论支撑[47]。Rahman等[52]发现, 空气中不同寄主适应型进化分支的葫芦霜霉病菌Pseudoperonospora cubensis孢子的首次检出时间和季节动态均存在差异, 为种植户提供了针对不同葫芦品种的精准防治方案。类似地, Carisse等[144]发现, 不同进化分支的葡萄霜霉病菌Plasmopara viticola孢子在不同品种上的相对丰度显著不同且存在一定竞争, 可作为葡萄霜霉病综合治理中风险指标的参考依据。Hellin等[45]通过监测空气中抗甾醇脱甲基抑制剂(sterol demethylation inhibitors, DMIs)和琥珀酸脱氢酶抑制剂(succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors, SDHIs)类杀菌剂的小麦发酵壳针孢Zymoseptoria tritici孢子分布, 指导杀菌剂合理选用。

基于病菌孢子捕捉数据制定的防治指标受气象条件、作物抗性水平、病害严重度、病菌生物学特性等因素的影响[42, 58]。当条件适于侵染和病害发展时, 少量病菌孢子就可造成较大的流行风险。因此, 除了孢子量外, 病菌孢子与环境或寄主互作的关系也应纳入决策支持系统, 以提供更精准的综合治理策略。

5" 结语与展望

近几十年来,受气候变化、耕作制度改变、植物种质资源和商品全球化贸易的影响,许多植物病原菌在世界范围内广泛传播[145]。地方流行病害和外来入侵病害分别呈现灾变和蔓延趋势。与此同时,迫于政府、消费者的双重压力,种植者必须采取更明智的病害防治策略以减轻对杀菌剂的依赖。因此,病害监测预警工作正面临严峻挑战[3]。自Gregory开创空气传播植物病害生物学研究以来[11],国内外学者承前启后、继往开来,与具有突发性、暴发性和流行性的多种气传病害展开了“持久战”“世纪战”,建立了基于空气中病菌孢子捕捉量的病害中、短期预测预报和风险评估模型,显著改善了植物病害综合治理水平。在此背景下,本文汇总了与病菌孢子捕捉和监测相关的代表性研究成果。

定量分子生物学的发展为在不同流行病学研究尺度上快速、准确地获取病菌孢子捕捉数据提供了强大的技术支撑,并能同时靶向多种病菌孢子[49,5859,109,114]。科学家也尝试将新兴的“现场快速检测技术”如等温PCR技术(LAMP-PCR或RPA-PCR)与自动化病菌孢子捕捉器相结合,为种植者和植保专家提供实时的风险预警[69,146]。此外,图像自动识别技术也在迅速发展,目前已在多种具有灾变性流行风险的粮食作物病害和导致毁灭性产量损失的经济作物病害上建立了病菌孢子的AI图像识别数据库,结合风险估计模型和相应的管理决策可即时的为用户提供最佳解决方案(https:∥www.scanittech.com或https:∥bioscout.com.au)。但基于孢子捕捉的病害管理所获得的经济效益同时取决于减少的杀菌剂投入成本和采样所需成本(包括购买、维护病菌孢子捕捉器和孢子计数与定量的成本),而后者相当昂贵,使得我国大多数仍保有精耕细作或小农经营模式的农户望而却步。随着土地流转政策的持续推进及农民专业合作社的发展,规模化、集约化的现代农业生产模式将成为经营主体。

未来,有望将病菌孢子监测网格与DNA分析、图像和数据分析技术结合,切实服务于农业现代化体系下的植物病害管理生产实践。

改革开放40余年来,我国科技步入快速发展轨道,农业科技创新体系整体效能显著提升,填补了病菌孢子捕捉和监测领域的多项研究空白[147],但与欧美科技强国之间的差距依然存在。我国基于病菌孢子捕捉的监测预警技术仍处于发展的初级阶段,特别是在基础研究领域和交叉前沿领域亟待攻关打破创新性瓶颈。当下,以物联网、大数据及人工智能等技术驱动的第四次工业革命正以前所未有的态势席卷全球。持续整合不断发展的新兴技术,改善数据获取、分析、解释和共享效率是大势所趋, 也是在“大数据”时代下实现病菌孢子捕捉技术网格化、信息化与智能化深度融合的必经之路。

参考文献

[1]" SHENASHEN M A, EMRAN M Y, EL S A, et al. Progress in sensory devices of pesticides, pathogens, coronavirus, and chemical additives and hazards in food assessment: Food safety concerns [J/OL]. Progress in Materials Science, 2022, 124: 100866. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2021.100866.

[2]" STRANGE R N, SCOTT P R. Plant disease: a threat to global food security [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2005, 43(1): 83116.

[3]" JEAN B R, PAMELA K A, DANIEL P B, et al. The persistent threat of emerging plant disease pandemics to global food security [J/OL]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2021, 118(23): e2022239118. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2022239118.

[4]" HUGHES G. The evidential basis of decision making in plant disease management [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2017, 80(4): 4159.

[5]" 封洪强, 姚青, 胡程, 等. 我国农作物病虫害智能监测预警技术新进展[J]. 植物保护, 2023, 49(5): 229242.

[6]" BROWN J K M, HOVMOLLER M S. Aerial dispersal of pathogens on the global and continental scales and its impact on plant disease [J]. Science, 2002, 297(5581): 537541.

[7]" SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, ROSS S D. Highways in the sky: Scales of atmospheric transport of plant pathogens [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2015, 53: 591611.

[8]" SINGH R P, HODSON D P, HUERTA-ESPINO J, et al. The emergence of Ug99 races of the stem rust fungus is a threat to world wheat production [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2011, 49(1): 465481.

[9]" ZENG Shimai, LUO Yong. Long-distance spread and interregional epidemics of wheat stripe rust in China [J]. Plant Disease, 2006, 90(8): 980988.

[10]GREGORY P H. The microbiology of the atmosphere [M]. 2nd ed. London: Leonard Hill Limited, 1973.

[11]LACEY J, LACEY M E, FITT B D L. Philip Herries Gregory 1907-1986: pioneer aerobiologist, versatile mycologist [J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 1997, 35: 114.

[12]GREGORY P H. The dispersion of airborne spores [J]. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 1945, 28(1/2): 2672.

[13]MCTNEY H A, FITT B D L, SCHMECHEL D. Sampling bioaerosols in plant pathology [J]. Journal of Aerosol Science, 1997, 28(3): 349364.

[14]WILLIAMS R H, WARD E, MCCARTNEY H A. Methods for integrated air sampling and DNA analysis for detection of airborne fungal spores [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2021, 67(6): 24532459.

[15]FITT B D L, CREIGHTON N F, BAINBRIDGE A. Role of wind and rain in dispersal of Botrytis fabae conidia [J]. Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 1985, 85(2): 307312.

[16]ROGERS S L, ATKINS S D, WEST J S. Detection and quantification of airborne inoculum of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum using quantitative PCR [J]. Plant Pathology, 2009, 58(2): 324331.

[17]WEST J S, ATKINS S D, EMBERLIN J, et al. PCR to predict risk of airborne disease [J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2008, 16(8): 380387.

[18]LACEY J. Spore dispersal — its role in ecology and disease: the British contribution to fungal aerobiology [J]. Mycological Research, 1996, 100(6): 641660.

[19]CHAMECKI M, DUFAULT N S, ISARD S A. Atmospheric dispersion of wheat rust spores: a new theoretical framework to interpret field data and estimate downwind dispersion [J]. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 2011, 51(3): 672685.

[20]HELLIN P, DUVIVIER M, DEDEURWAERDER G, et al. Evaluation of the temporal distribution of Fusarium graminearum airborne inoculum above the wheat canopy and its relationship with Fusarium head blight and DON concentration [J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2018, 151(4): 10491064.

[21]HEMMATI F, PELL J K, MCCARTNEY H A, et al. Airborne concentrations of conidia of Erynia neoaphidis above cereal fields [J]. Mycological Research, 2011, 105(4): 485489.

[22]MORAIS D, SACHE I, SUFFERT F, et al. Is the onset of Septoria tritici blotch epidemics related to the local pool of ascospores [J]. Plant Pathology, 2016, 65(2): 250260.

[23]PAULITZ T C, DUTILLEUL P, YAMASAKI S H, et al. A generalized two-dimensional Gaussian model of disease foci of head blight of wheat caused by Gibberella zeae [J]. Phytopathology, 1999, 89(1): 7483.

[24]REICH J, CHATTERTON S, JOHNSON D. Temporal dynamics of Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in seed alfalfa fields of southern Alberta, Canada [J]. Plant Disease, 2016, 101(2): 331343.

[25]ALDERMAN S C. Aerobiology of Claviceps purpura in Kentucky bluegrass [J]. Plant Disease, 1993, 77(10): 10451049.

[26]CHAREST J, DEWDNEY M, PAULITZ T, et al. Spatial distribution of Venturia inaequalis airborne ascospores in orchards [J]. Phytopathology, 2002, 92(7): 769779.

[27]CARISSE O, BACON R, LEFEBVRE A. Grape powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) risk assessment based on airborne conidium concentration [J]. Crop Protection, 2009, 28(12): 10361044.

[28]AYLOR D E. Vertical variation of airborne concentration of Venturia inaequalis ascospores in an apple orchard [J]. Phytopathology, 1995, 85(2): 175181.

[29]CARISSE O, MCCARTNEY H A, GAGNON J A, et al. Quantification of airborne inoculum as an aid in the management of leaf blight of onion caused by Botrytis squamosa [J]. Plant Disease, 2005, 89(7): 726733.

[30]CARISSE O, TREMBLAY D M, LVESQUE C A, et al. Development of a TaqMan real-time PCR assay for quantification of airborne conidia of Botrytis squamosa and management of Botrytis leaf blight of onion [J]. Phytopathology, 2009, 99(11): 12731280.

[31]WEST J S, CANNING G G M, PERRYMAN S A, et al. Novel technologies for the detection of Fusarium head blight disease and airborne inoculum [J]. Tropical Plant Pathology, 2017, 42(3): 203209.

[32]GENT D H, NELSON M E, FARNSWORTH J L, et al. PCR detection of Pseudoperonospora humuli in air samples from hop yards [J]. Plant Pathology, 2009, 58(6): 10811091.

[33]KUNJETI S G, ANCHIETA A, MARTIN F N, et al. Detection and quantification of Bremia lactucae by spore trapping and quantitative PCR [J]. Phytopathology, 2016, 106(11): 14261437.

[34]FALACY J S, GROVE G G, MAHAFFEE W F, et al. Detection of Erysiphe necator in air samples using the polymerase chain reaction and species-specific primers [J]. Phytopathology, 2007, 97(10): 12901297.

[35]王奥霖, 商昭月, 张美惠, 等. 基于病菌孢子捕捉和real-time PCR技术的田间空气中小麦白粉病菌孢子动态监测及病情估计模型研究[J]. 植物保护, 2024, 50(2): 4956.

[36]WALTER F M, FABIEN M, LUCAS U, et al. Catching spores: Linking epidemiology, pathogen biology, and physics to ground-based airborne inoculum monitoring [J]. Plant Disease, 2023, 107(1): 1333.

[37]马占鸿. 植病流行学[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2010.

[38]MILLER N E, STOLL R, MAHAFFEE W F, et al. An experimental study of momentum and heavy particle transport in a trellised agricultural canopy [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2015(211/212): 100114.

[39]MILLER N E, STOLL R, MAHAFFEE W F, et al. Mean and turbulent flow statistics in a trellised agricultural canopy [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2017, 165(1): 113143.

[40]AARON Ⅱ J P, LI Qing, RIMY M, et al. Monitoring the long-distance transport of Fusarium graminearum from field-scale sources of inoculum [J]. Plant Disease, 2014, 98(4): 504511.

[41]AARON Ⅱ J P, MARR L C, SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, et al. Experimental validation of a long-distance transport model for plant pathogens: Application to Fusarium graminearum [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2015, 203: 118130.

[42]FALL M L, VAN DER HEYDEN H, BRODEUR L, et al. Spatiotemporal variation in airborne sporangia of Phytophthora infestans: characterization and initiative toward improving potato late blight risk estimation [J]. Plant Pathology, 2015, 64(1): 178190.

[43]CARISSE O, TREMBLAY D M, LEFEBVRE A. Comparison of Botrytis cinerea airborne inoculum progress curves from raspberry, strawberry and grape plantings [J]. Plant Pathology, 2014, 63(5): 983993.

[44]FRAAIJE B A, COOLS H J, FOUNTAINE J, et al. Role of ascospores in further spread of QoI-resistant cytochrome b alleles (G143A) in field populations of Mycosphaerella graminicola [J]. Phytopathology, 2005, 95(8): 933941.

[45]HELLIN P, DUVIVIER M, CLINCKEMAILLIE A, et al. Multiplex qPCR assay for simultaneous quantification of CYP51-S524T and SdhC-H152R substitutions in European populations of Zymoseptoria tritici [J]. Plant Pathology, 2020, 69(9): 16661677.

[46]NICOLAISEN M, WEST J S, SAPKOTA R, et al. Fungal communities including plant pathogens in near surface air are similar across northwestern Europe [J/OL]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 1729. DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01729.

[47]JACKSON S L, BAYLISS K L. Spore traps need improvement to fulfil plant biosecurity requirements [J]. Plant Pathology, 2011, 60(5): 801810.

[48]《实验动物与比较医学》编辑部.《中华人民共和国生物安全法》: 防控重大新发突发传染病、动植物疫情[J]. 实验动物与比较医学, 2021, 41(5): 442.

[49]CHEN Wen, HAMBLETON S, SEIFERT K A, et al. Assessing performance of spore samplers in monitoring aeromycobiota and fungal plant pathogen diversity in Canada [J/OL]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 84(9): e02601-17. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02601-17.

[50]HIRST J M, HURST G H, HOGG W H. Long-distance spore transport: Methods of measurement, vertical spore profiles and the detection of immigrant spores [J]. Journal of General Microbiology, 1967, 48(3): 329355.

[51]AYLOR D E. The aerobiology of apple scab [J]. Plant Disease, 1998, 82(8): 838849.

[52]RAHMAN A, STANDISH J, D’ARCANGELO K N, et al. Clade-specific biosurveillance of Pseudoperonospora cubensis using spore traps for precision disease management of cucurbit downy mildew [J]. Phytopathology, 2020, 111(2): 312320.

[53]COHEN Y, ROTEM J. Dispersal and viability of sporangia of Pseudoperonospora cubensis [J]. Transactions British Mycological Society, 1971, 57(1): 6774.

[54]STANSBURY C D, MCKIRDY S J, DIGGLE A J, et al. Modeling the risk of entry, establishment, spread, containment, and economic impact of Tilletia indica, the cause of Karnal bunt of wheat, using an Australian context [J]. Phytopathology, 2002, 92(3): 321331.

[55]PAN Zaitao, YANG Xiaobing, PIVONIA S, et al. Long-term prediction of soybean rust entry into the continental United States [J]. Plant Disease, 2006, 90(7): 840846.

[56]KLJUN N, ROTACH M W, SCHMID H P. A three-dimensional backward Lagrangian footprint model for a wide range of boundary-layer stratifications [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2002, 103(2): 205226.

[57]LI Yuxiang, DAI Jichen, ZHANG Taixue, et al. Genomic analysis, trajectory tracking and field investigation of wheat stripe rust pathogen reveal sources and their migration routes contributing to disease epidemics in China [J/OL]. Plant Communications, 2023, 4: 100563. DOI: 10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100563.

[58]CARISSE O, LEVASSEUR A, VAN DER HEYDEN H. A new risk indicator for Botrytis leaf blight of onion caused by Botrytis squamosa based on infection efficiency of airborne inoculum [J]. Plant Pathology, 2012, 61(6): 11541164.

[59]VAN DER HEYDEN H, CARISSE O, BRODEUR L. Comparison of monitoring based indicators for initiating fungicide spray programs to control Botrytis leaf blight of onion [J]. Crop Protection, 2012, 33: 2128.

[60]THIESSEN L D, KEUNE J A, NEILL T M, et al. Development of a grower-conducted inoculum detection assay for management of grape powdery mildew [J]. Plant Pathology, 2016, 65: 238249.

[61]BRACHACZEK A, KACZMAREK J, JEDRYCZKA M. Monitoring blackleg (Leptosphaeria spp.) ascospore release timing and quantity enables optimal fungicide application to improved oilseed rape yield and seed quality [J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2016, 145(3): 643657.

[62]CAO Xueren, YAO Dongming, ZHOU Yilin, et al. Detection and quantification of airborne inoculum of Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici using quantitative PCR [J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2016, 146(1): 225229.

[63]WEST J S, FITT B D L, LEECH P K, et al. Effects of timing of Leptosphaeria maculans ascospore release and fungicide regime on Phoma leaf spot and Phoma stem canker development on winter oilseed rape (Brassica napus) in southern England [J]. Plant Pathology, 2002, 51(4): 454463.

[64]BRISCHETTO C, BOVE F, LANGUASCO L, et al. Can spore sampler data be used to predict Plasmopara viticola infection in vineyards [J/OL]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2020, 11: 1187. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01187.

[65]CAO Xueren, YAO Dongming, XU Xiangming, et al. Development of weather- and airborne inoculum-based models to describe disease severity of wheat powdery mildew [J]. Plant Disease, 2014, 99(3): 395400.

[66]DHAR N, MAMO B E, SUBBARAO K, et al. Measurements of aerial spore load by qPCR facilitates lettuce downy mildew risk advisement [J]. Plant Disease, 2019, 104(1): 8293.

[67]PARDYJAK E R, SPECKART S O, YIN F, et al. Near source deposition of vehicle generated fugitive dust on vegetation and buildings: Model development and theory [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2008, 42: 64426452.

[68]GONZLEZ-FERNNDEZ E, PIA-REY A, FERNNDEZ-GONZLEZ M, et al. Identification and evaluation of the main risk periods of Botrytis cinerea infection on grapevine based on phenology, weather conditions and airborne conidia [J]. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 2020, 158(1/2): 8898.

[69]LEES A, ROBERTS D M, LYNOTT J, et al. Real-time PCR and LAMP assays for the detection of spores of Alternaria solani and sporangia of Phytophthora infestans to inform disease risk forecasting [J]. Plant Disease, 2019, 103(12): 31723180.

[70]ISARD S A, BARNES C W, HAMBLETON S, et al. Predicting soybean rust incursions into the North American continental interior using crop monitoring, spore trapping, and aerobiological modeling [J]. Plant Disease, 2011, 95(11): 13461357.

[71]HU Xuemin, FU Songping, LI Yuxiang, et al. Dynamics of Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici urediniospores in Longnan, a critical oversummering region of China [J]. Plant Disease, 2023, 107(10): 31553163.

[72]谷医林, 王翠翠, 初炳瑶, 等. 甘谷县春季空气中小麦条锈菌孢子动态的监测及其与气象因素的相关性分析[J]. 植物保护学报, 2018, 45(1): 161166.

[73]GU Yilin, LI Yong, WANG Cuicui, et al. Inter-seasonal and altitudinal inoculum dynamics for wheat stripe rust and powdery mildew epidemics in Gangu, Northwestern China [J]. Crop Protection, 2018, 110: 6572.

[74]AYLOR D E, TAYLOR G. Escape of Peronospora tabacina spores from a field of diseased tobacco plants [J]. Phytopathology, 1983, 73(4): 525529.

[75]AYLOR D E, FRY W E, MAYTON H, et al. Quantifying the rate of release and escape of Phytophthora infestans sporangia from a potato canopy [J]. Phytopathology, 2001, 91(12): 11891196.

[76]LIMPERT E, GODET F, MLLER K. Dispersal of cereal mildews across Europe [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 1999. 97(4): 293308.

[77]NEUFELD K N, ISARD S A, OJIAMBO P S. Relationship between disease severity and escape of Pseudoperonospora cubensis sporangia from a cucumber canopy during downy mildew epidemics [J]. Plant Pathology, 2013, 62(6): 13661377.

[78]CHOUDHURY R A, KOIKE S T, FOX A D, et al. Spatiotemporal patterns in the airborne dispersion of spinach downy mildew [J]. Phytopathology, 2016, 107(1): 5058.

[79]FERNANDO W G D, PAULITZ T C, SEAMAN W L, et al. Head blight gradients caused by Gibberella zeae from area sources of inoculum in wheat field plots [J]. Phytopathology, 1997, 87(4): 414421.

[80]AYLOR D E, SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, SHIELDS E J, et al. Tracking the potato late blight pathogen in the atmosphere using unmanned aerial vehicles and Lagrangian modeling [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2011, 151(2): 251260.

[81]BLANCO C, DE S B L, ROMERO F. Relationship between concentrations of Botrytis cinerea conidia in air, environmental conditions, and the incidence of grey mold in strawberry flowers and fruits [J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2006, 114(4): 415425.

[82]CAO Xueren, DUAN Xiayu, ZHOU Yilin, et al. Dynamics in concentrations of Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici conidia and its relationship to local weather conditions and disease index in wheat [J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2012, 132(4): 525535.

[83]CARISSE O, MORISSETTE-THOMAS V, VAN DER HEYDEN H. Lagged association between powdery mildew leaf severity, airborne inoculum, weather, and crop losses in strawberry [J]. Phytopathology, 2013, 103(8): 811821.

[84]FALL M L, VAN DER HEYDEN H, BEAULIEU C, et al. Bremia lactucae infection efficiency in lettuce is modulated by temperature and leaf wetness duration under Quebec field conditions [J]. Plant Disease, 2015, 99(7): 10101019.

[85]AGUAYO J, FOURRIER-JEANDEL C, HUSSON C, et al. Assessment of passive traps combined with high-throughput sequencing to study airborne fungal communities [J/OL]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 84(11): e02637-17. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02637-17.

[86]OVASKAINEN O, ABREGO N, SOMERVUO P, et al. Monitoring fungal communities with the global spore sampling project [J/OL]. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 2020, 7: 511. DOI: 10.3389/fevo.2019.00511.

[87]CARISSE O, SAVARY S, WILLOCQUET L. Spatiotemporal relationships between disease development and airborne inoculum in unmanaged and managed Botrytis leafblight epidemics [J]. Phytopathology, 2018, 98(1): 3844.

[88]XU Xiangming, BUTT D J, RIDOUT U S. Temporal patterns of airborne conidia of Podosphaera leucotricha, causal agent of apple powdery mildew [J]. Plant Pathology, 1995, 44(6): 944955.

[89]WEST J S, KIMBER R B E. Innovations in air sampling to detect plant pathogens [J]. Annals of Applied Biology, 2015, 166(1):417.

[90]HIRST J M. An automatic volumetric spore trap [J]. Annals of Applied Biology, 1952, 39(2): 257265.

[91]AYLOR D E. Airborne dispersion of pollen and spores [M]. Minnesota: The American Phytopathological Society Saint-Paul Minesota, 2017.

[92]PRUSSIN Ⅱ A J, SZANYI N A, WELLING P I, et al. Estimating the production and release of ascospores from a field-scale source of Fusarium graminearum inoculum [J]. Plant Disease, 2014, 98: 497503.

[93]GILET T, BOUROUIBA L. Fluid fragmentation shapes rain-induced foliar disease transmission [J/OL]. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2015, 12(104): 20141092. DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2014.1092.

[94]LINDEMANN J, UPPER C D. Aerial dispersal of epiphytic bacteria over bean plants [J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1985, 50(5): 12291232.

[95]MORRIS C E, SANDS D C, GLAUX C, et al. Urediospores of rust fungi are ice nucleation active at gt;-10℃ and harbor ice nucleation active bacteria [J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 2013, 13(8): 42234233.

[96]MORRIS C E, SANDS D C, GLAUX C, et al. Urediospores of Puccinia spp. and other rusts are warm-temperature ice nucleators and harbor ice nucleation active bacteria [J]. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 2012, 12(10): 2614326171.

[97]NOLL K E. A rotary inertial impactor for sampling giant particles in the atmosphere [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 1970, 4(1): 919.

[98]EDMONDS R L. Collection efficiency of Rotorod samplers for sampling fungus spores in the atmosphere [J]. Plant Disease Reporter, 1972, 56(8): 704708.

[99]PAUL P A, EL-ALLAF S M, LIPPS P E, et al. Rain splash dispersion of Gibberella zeae within wheat canopies in Ohio [J]. Phytopathology, 2004, 94(12): 13421349.

[100]PHILLIP L M, KARI A P. Spore dispersal patterns of Colletotrichum fioriniae in orchards and the timing of apple bitter rot infection periods [J]. Plant Disease, 2023, 107(8): 24742482.

[101]QUALEN R V, YANG Xiaobing. Spore traps help researchers watch for soybean rust [DB/OL]. Database (Iowa State University), 2006: 185. https:∥lib.dr.iastate.edu/cropnews/1308.

[102]VAN DER HEYDEN H, DUTILLEUL P, BRODEUR L, et al. Spatial distribution of single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to fungicide resistance and implications for sampling [J]. Phytopathology, 2014, 104(6): 604613.

[103]THIESSEN L D, KEUNE J A, NEILL T M, et al. Development of a grower-conducted inoculum detection assay for management of grape powdery mildew [J]. Plant Pathology, 2016, 65(2): 238249.

[104]SCHOLTHOF K B G. The disease triangle: Pathogens, the environment and society [J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2007, 5(1): 152156.

[105]AYLOR D E. A framework for examining inter-regional aerial transport of fungal spores [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 1986, 8(4): 263288.

[106]HIRST J M. Changes in atmospheric spore content: Diurnal periodicity and the effects of weather [J]. Transactions British Mycological Society, 1953, 36(4): 375393.

[107]FERNANDO W G D, MILLER J D, SEAMAN W L, et al. Daily and seasonal dynamics of airborne spores of Fusarium graminearum and other Fusarium species sampled over wheat plots [J]. Canadian Journal of Botany-Revue Canadienne de Botanique, 2000, 78(4): 497505.

[108]PAULITZ T C. Diurnal release of ascospores by Gibberella zeae in inoculated wheat plots [J]. Plant Disease, 1996, 80: 674678.

[109]CARISSE O, VAN DER HEYDEN H. Networked real time disease risk evaluation: A cost-effective approach to disease management [J]. Phytopathology, 2017, 107(12): 145147.

[110]SEVERNS P M, SACKETT K E, FARBER D H, et al. Consequences of long-distance dispersal for epidemic spread: patterns, scaling, and mitigation [J]. Plant Disease, 2018, 103(2): 177191.

[111]KLOSTERMAN S J, ANCHIETA A, MCROBERTS N, et al. Coupling spore traps and quantitative PCR assays for detection of the downy mildew pathogens of spinach (Peronospora effusa) and beet (P.schachtii) [J]. Phytopathology, 2014, 104(12): 13491359.

[112]刘伟, 赵亚男, 韩翠仙, 等. 小麦白粉病菌分生孢子田间传播的初步研究[J]. 植物保护, 2020, 46(3): 4751.

[113]王奥霖. 田间空气中小麦白粉菌分生孢子的动态监测及远程传播气流轨迹分析[D]. 北京: 中国农业科学院, 2021.

[114]WANG Aolin, SHANG Zhaoyue, JIANG Ru, et al. Development and application of a qPCR-based method coupled with spore trapping to monitor airborne pathogens of wheat causing stripe rust, powdery mildew, and Fusarium head blight [J/OL]. Plant Disease, 2024. DOI: 10.1094/PDIS-03-24-0548-SR.

[115]MAHAFFEE W F, STOLL R. The ebb and flow of airborne pathogens: Monitoring and use in disease management decisions [J]. Phytopathology, 2016, 106(5): 420431.

[116]MADDEN L V, HUGHES G. Sampling for plant disease incidence [J]. Phytopathology, 1999, 89(11): 10881103.

[117]AYLOR D E, IRWIN M E. Aerial dispersal of pests and pathogens: implications for integrated pest management [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 1999, 97(4): 233234.

[118]SKELSEY P, ROSSING W A H, KESSEL G J T, et al. Scenario approach for assessing the utility of dispersal information in decision support for aerially spread plant pathogens, applied to Phytophthora infestans [J]. Phytopathology, 2009, 99(7): 887895.

[119]RIEUX A, SOUBEYRAND S, BONNOT F, et al. Long-distance wind-dispersal of spores in a fungal plant pathogen: Estimation of anisotropic dispersal kernels from an extensive field experiment [J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(8): e103225. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103225.

[120]AYLOR D E, ANAGNOSTAKIS S L. Active discharge distance of ascospores of Venturia inaequalis [J]. Phytopathology, 1991, 81(4): 548551.

[121]WAGGNONER P E. The removal of Helminthosporium maydis spores by wind [J]. Phytopathology, 1973, 63(10): 12521255.

[122]AYLOR D E. Force required to detach conidia of Helminthosporium maydis [J]. Plant Physiology, 1975, 55: 99101.

[123]AIST J R, AYLOR D E, PARLANGE J Y. Ultrastructure and mechanics of the conidium-conidiophore attachment of Helminthosporium maydis [J]. Phytopathology, 1976, 66(9): 10501055.

[124]KLJUN N, CALANCA P, ROTACH M W, et al. A simple parameterization for flux footprint predictions [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2004, 112(3): 503523.

[125]MARGAIRAZ F, ESHAGH H, HAYATI A N, et al. Development and evaluation of an isolated-tree flow model for neutral-stability conditions [J/OL]. Urban Climate, 2022, 42: 101083. DOI: 10.1016/j.uclim.2022.101083.

[126]BAILEY B N, STOLL R. Turbulence in sparse, organized vegetative canopies: A large-eddy simulation study [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2013, 147(3): 369400.

[127]BAILEY B N, STOLL R, PARDYJAK E R, et al. Effect of vegetative canopy architecture on vertical transport of massless particles [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 95: 480489.

[128]TORKELSON G, PRICE T A, STOLL R. Momentum and turbulent transport in sparse, organized vegetative canopies [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 2022, 184(1): 124.

[129]RAUPACH M R. Drag and drag partition on rough surfaces [J]. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 1992, 60(4): 375395.

[130]MILLER N E, STOLL R, MAHAFFEE W F, et al. Heavy particle transport in a trellised agricultural canopy during non-row-aligned winds [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2018(256/257): 125136.

[131]DEDEURWAERDER G, DUVIVIER M, MVUYENKURE S, et al. Spore traps network: a new tool for predicting epidemics of wheat yellow rust [J]. Communications in Agricultural and Applied Biological Sciences, 2011, 76(4): 667670.

[132]GONZALEZ F, GLASSOCK R, DUMBLETON S. Flying spore trap airborne based surveillance: towards a biosecure Australia [Z]. 2011.

[133]HIRST J M, HURST G H, HURST G H. Long-distance spore transport: Vertical sections of spore clouds over the sea [J]. Journal of General Microbiology, 1967, 48(3): 357377.

[134]AYLOR D E, BOEHM M T, SHIELDS E J. Quantifying aerial concentrations of maize pollen in the atmospheric surface layer using remote-piloted airplanes and Lagrangian stochastic modeling [J]. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 2006, 45(7): 10031015.

[135]SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, DINGUS B R, REINHOLTZ C. Development and application of an autonomous unmanned aerial vehicle for precise aerobiological sampling above agricultural fields [J]. Journal of Field Robotics, 2008, 25(3): 133147.

[136]LIN B, ROSS S D, PRUSSIN Ⅱ A J, et al. Seasonal associations and atmospheric transport distances of fungi in the genus Fusarium collected with unmanned aerial vehicles and ground-based sampling devices [J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2014, 94: 385391.

[137]TECHY L, SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, WOOLSEY C A. Coordinated aerobiological sampling of a plant pathogen in the lower atmosphere using two autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles [J]. Journal of Field Robotics, 2010, 27(3): 335343.

[138]MALDONADO-RAMIREZ S L, SCHMALE Ⅲ D G, SHIELDS E J, et al. The relative abundance of viable spores of Gibberella zeae in the planetary boundary layer suggests the role of long-distance transport in regional epidemics of Fusarium head blight [J]. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 2005, 132(1): 2027.

[139]GOTTWALD T R, TEDDERS W L. A spore and pollen trap for use on aerial remotely piloted vehicles [J]. Phytopathology, 1985, 75(7): 801807.

[140]GONZALEZ F, CASTRO M P G, NARAYAN P, et al. Development of an autonomous unmanned aerial system to collect time-stamped samples from the atmosphere and localize potential pathogen sources [J]. Journal of Robotic Systems, 2011, 28(6): 961976.

[141]FLEISCHER S J, BLOM P E, WEISZ R. Sampling in precision IPM: When the objective is a map [J]. Phytopathology, 1999, 89(11): 11121118.

[142]LACY M L, PONTIUS G A. Prediction of weather-mediated release of conidia of Botrytis squamosa from onion leaves in the fields [J]. Phytopathology, 1983, 73(5): 670676.

[143]FALL M L, TREMBLAY D M, GOBEIL-RICHARD M, et al. Infection efficiency of four Phytophthora infestans clonal lineages and DNA-based quantification of sporangia [J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(8): e0136312. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136312.

[144]CARISSE O, TREMBLAY D M, HBERT P O, et al. Evidence for differences in the temporal progress of Plasmopara viticola clades riparia and aestivalis airborne inoculum monitored in vineyards in eastern Canada using a specific multiplex qPCR assay [J]. Plant Disease, 2021, 105(6): 16661676.

[145]WANG Chenzhi, WANG Xuhui, JIN Zhenong, et al. Occurrence of crop pests and diseases has largely increased in China since 1970 [J]. Nature Food, 2022, 3(1): 5765.

[146]MLISSA S A, GUILLAUME J B, DAVID M T, et al. Development of real-time isothermal amplification assays for on-site detection of Phytophthora infestans in potato leaves [J]. Plant Disease, 2017, 101(7): 12691277.

[147]胡小平, 户雪敏, 马丽杰, 等. 作物病害监测预警研究进展[J]. 植物保护学报, 2022, 49(1): 298315.

(责任编辑:杨明丽)