灰比诺葡萄病毒内蒙古分离物全基因组分析

摘" " 要:【目的】获取灰比诺葡萄病毒(grapevine pinot gris virus,GPGV)内蒙古分离物全基因组序列,并对该病毒群体进行序列一致性、系统发育、基因重组以及群体遗传多样性等分析。【方法】以GPGV阳性样品为试验材料,通过RT-PCR技术和cDNA末端快速扩增技术(rapid amplification of cDNA ends,RACE)克隆GPGV内蒙古分离物的全基因组序列,并通过分子生物学分析软件对其进行基因组序列分析。【结果】成果克隆了2条GPGV内蒙古分离物(20IM-ViVi1和20IM-ViVi2)的全基因组序列,序列全长均为7250 nt,且均编码3个ORFs;序列一致性分析结果显示,20IM-ViVi1与20IM-ViVi2基因组序列核苷酸一致率为96.4%,与其他分离物的全基因组序列一致率分别为79.7%~96.8%、79.5%~97.7%;系统进化分析表明,GPGV所有全基因组分离物可划为4个分支,其中本研究中所获得的2个分离物20IM-ViVi1与20IM-ViVi2均聚集在第Ⅰ分支,并均与中国夏黑分离物SRR2845691-GPGV亲缘关系最近;遗传多样性分析结果表明,GPGV具有较高的遗传多样性,其中GPGV亚洲分离物遗传多样性最高。【结论】首次获得GPGV内蒙古分离物的全基因组序列,并阐述了2个GPGV内蒙古分离物与已知病毒之间的进化关系,可为中国GPGV株系划分、遗传进化研究奠定理论基础。

关键词:灰比诺葡萄病毒;系统进化分析;序列一致性;遗传多样性

中图分类号:S663.1;S436.631 文献标志码:A 文章编号:1009-9980(2024)12-2425-11

Complete genome sequence analysis of grapevine pinot gris virus isolates from Inner Mongolia

GUO Mengze, XU Lei, YAN Yuting, SUN Pingping, ZHANG Lei, LI Zhengnan*

(1College of Horticulture and Plant Protection, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot 010018, Inner Mongolia, China)

Abstract: 【Objective】 The objective of this study was to acquire the complete genomic sequence of grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV) isolates from Inner Mongolia and to perform a comprehensive analysis of the GPGV population, encompassing sequence identity, phylogenetic relationships, gene recombination, sequence similarity and genetic diversity. 【Methods】 Grape leaf samples that had previously tested positive for GPGV served as the experimental materials for total RNA extraction. A total of 100 mg of GPGV-infected grape samples were processed in accordance with the Spectrum™ Plant Total RNA Kit instructions. The quality and concentration of the extracted RNA were evaluated via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and microspectrophotometry, respectively, and the RNA was preserved at -80 ℃ for future use. Vector NTI software was utilized to align all the full-length genomic sequences of GPGV reported in the NCBI GenBank database. Three primer pairs (GPGV-1F/GPGV-1R, GPGV-2F/GPGV-2R and GPGV-3F/GPGV-3R) were designed within the conserved regions to amplify the complete genomic sequence of GPGV, ensuring that overlapping fragments between adjacent amplification products exceeded 200 bp. Subsequently, primers (GPGV3 and GPGV1) were designed for amplifying the terminal sequences of GPGV. Total RNA was employed as a template to synthesize cDNA using the SuperScript™ Ⅲ Reverse Transcriptase Kit under the conditions of 50 ℃ for 1 hour, followed by 70 ℃ for 15 minutes. The cDNA template was then used to amplify the nucleotide sequences of GPGV with Q5 High-Fidelity 2×Master Mix, employing thermal cycling parameters of denaturation at 98 ℃ for 30 seconds, annealing at 56 ℃ for 30 seconds, and extension at 72 ℃ for 2 minutes over 35 cycles. The SMARTer® RACE 5'/3' Kit was used to amplify the 5' and 3' terminal sequences of GPGV. PCR products were identified through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the target fragments were purified using a gel DNA purification kit. The amplified and RACE-obtained GPGV genomic sequences were assembled using Vector NTI software to reconstruct the complete genomic sequences of GPGV. ClustalW in MEGA 11 was employed to conduct multiple sequence alignments of all complete genomic sequences of GPGV in the NCBI database (152 isolates), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum-Likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates as determined by the MODLES program. Sequence identity analysis was performed on the complete genomic sequences and open reading frames (ORFs) using BioEdit 7.2 software. Recombination analysis was executed on the complete genomic sequences of the isolates using seven recombination detection algorithms provided by RDP4 software. Population neutrality tests, selection pressure analysis, nucleotide polymorphism analysis, and haplotype polymorphism analysis were conducted on GPGV isolates using DnaSP v.6.12.03. 【Results】 The complete genomes of two GPGV isolates from Inner Mongolia (20IM-ViVi1 and 20IM-ViVi2) were successfully cloned, each comprising 7250 nucleotides and encoding three open reading frames (ORFs). Sequence identity analysis demonstrated that the genome sequences of isolates 20IM-ViVi1 and 20IM-ViVi2 were 96.4% identical. Their identity with other isolates varied from 79.7% to 96.8% and 79.5% to 97.7%, respectively. Furthermore, the identity among the full genome sequences of GPGV isolates in China spanned from 82.0% to 99.9%. A phylogenetic tree based on the complete genome sequences of all GPGV isolates revealed that the existing 152 complete genomes were partitioned into four clades. Clade Ⅲ and Clade Ⅳ were further divided into two minor subclades (a and b). The two isolates 20IM-ViVi1 and 20IM-ViVi2 obtained in this study were both grouped in CladeⅠ and were most closely related to the Summer Black grape isolate SRR2845691-GPGV from China. A phylogenetic tree constructed from Chinese GPGV isolates indicated that these isolates were predominantly divided into four clades. The GPGV isolate Shihezi-1 from Xinjiang displayed a relatively high genetic distance from other isolates, with a distant phylogenetic relationship, and was therefore placed in CladeⅠ separately. The isolates 20IM-ViVi1 and 20IM-ViVi2 obtained in this study were both aggregated in Clade Ⅳ and were most closely related to the Summer Black grape isolate SRR2845691-GPGV. Recombination analysis revealed that no significant recombination events were detected in the GPGV isolates 20IM-ViVi1 and 20IM-ViVi2. Genetic diversity analysis suggested that GPGV possessed high genetic diversity, with the Asian isolates showing the highest genetic diversity. 【Conclusion】 This study marks the first to obtain the complete genome sequences of GPGV isolates from Inner Mongolia. Both GPGV isolates had a genome length of 7250 nt, containing three ORFs, and exhibited high identity with existing GPGV isolates (excluding the Japanese isolate H-JP2), with identity ranges from 79.7% to 96.8% and 79.5% to 97.7%, respectively. Additionally, the phylogenetic tree constructed from all GPGV complete genome sequences was divisible into four clades, with the isolates obtained in this study clustering in CladeⅠ. Genetic diversity analysis revealed that Asian GPGV isolates exhibited high genetic diversity, potentially indicating an origin center, although population expansion occurred in Europe. This study represents the first comprehensive analysis of GPGV isolates from Inner Mongolia, providing critical insights into their genomic structure and evolutionary dynamics.

Key words: Grapevine pinot gris virus; Phylogenetic analysis; Sequence identity; Genetic diversity

葡萄(Vitis vinifera)是有较高营养价值和经济价值的一种园艺作物[1]。据粮农组织(FAO)统计,2021年,中国葡萄产量为1 126.99万t,位居世界第一;种植面积为58.272 8万hm2,位居世界第四。但近年来中国葡萄产区病毒性病原日益流行,葡萄已知的病毒性病原种类超过100种[2-4],成为感染病毒种类最多的果树。目前,葡萄感染病毒后一般会出现发芽延迟、节间缩短、叶片畸形、浆果坏死、浆果变酸、花叶、斑驳、脉明、环斑以及木质部凹陷等症状[5-6],严重影响葡萄产业的发展。

灰比诺葡萄病毒(grapevine pinot gris virus,GPGV)是乙型线形病毒科(Betafexiviridae)纤毛病毒属(Trichovirus)的代表成员,基因组为正义单链RNA分子,编码3个重叠的开放阅读框(open reading frame,ORF),ORF1编码RNA依赖的RNA聚合酶(RNA-dependent RNA polymerase,RdRp)、ORF2编码运动蛋白(movement protein,MP)、ORF3编码外壳蛋白(coat protein,CP)。GPGV所引起的葡萄病害最早始于意大利特伦蒂诺地区葡萄园种植的灰比诺上[1]。但该病毒是在9 a(年)后才被发现,随后世界上大多数主要的葡萄种植区都检测到了GPGV,例如欧洲的法国、德国、俄罗斯、捷克、希腊、斯洛伐克、斯洛文尼亚、土耳其、西班牙和葡萄牙;亚洲的中国、韩国和巴基斯坦;北美洲的美国、加拿大;南美洲的乌拉圭;大洋洲的澳大利亚[7-17]。目前,GPGV在中国葡萄主要种植区较为流行,可造成葡萄叶片斑驳和变形病(grapevine leaf mottling and deformation,GLMD),并且浆果酸度增加,严重影响葡萄以及葡萄酒产业的发展。但是一些几乎无症状的葡萄样本也检测到了GPGV,因此这些症状相关的原因尚不清楚[18]。此外,白花蝇子草(Silene latifolia)和藜(Chenopodium album)是GPGV的草本寄主[19],葡萄缺节瘿螨(Colomerus newkirk)是GPGV传播的昆虫介体[20]。

近年来,GPGV的基因组特征、危害症状、地理分布和起源中心受到了广泛关注,较多研究表明GPGV种群的遗传多样性处于中等水平,且中国也是起源中心的主要指向之一[17]。然而,关于GPGV中国分离物的全基因组序列报道较少。因此,为了深入了解GPGV的遗传多样性和系统发育关系,利用RT-PCR和RACE技术获得了2条GPGV的内蒙古分离物(20IM-ViVi1和20IM-ViVi2),并将其与NCBI GenBank 数据库所下载的其他GPGV分离物进行了序列一致性分析、系统发育分析、重组分析以及遗传多样性分析,以期为中国GPGV的防治提供理论基础。

1 材料和方法

1.1 材料

试验材料为前期研究中检测为GPGV阳性的葡萄叶片样品,分别于2020年6月8日和2020年7月15日在内蒙古呼和浩特市周边不同的设施葡萄园采集,并经液氮速冻后存放于-80 ℃冰箱备用。

1.2 总RNA提取

取上述感染GPGV的葡萄样品100 mg,按照植物总RNA提取试剂盒(Spectrum™ Plant Total RNA Kit)说明书进行总RNA的提取,通过1%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳和微量分光光度计分别对所提取RNA的质量和浓度进行检测,并于-80 ℃冰箱保存备用。

1.3 引物设计

利用Vector NTI软件对NCBI Genbank数据库已报道的所有GPGV全长基因组序列进行序列比对,在序列保守区设计了3个引物对(GPGV-1F/GPGV-1R、GPGV-2F/GPGV-2R、GPGV-3F/GPGV-3R)用于GPGV全基因组序列扩增,相邻扩增片段间重叠片段长度均大于200 bp,随后结合上述扩增结果设计了用于扩增GPGV末端序列的引物(GPGV3、GPGV1)(表1)。引物均由生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司合成。

1.4 GPGV全基因组序列扩增

以提取的总RNA为模板,采用反转录试剂盒(SuperScript™ Ⅲ Reverse Transcriptase)合成cDNA,反应条件:50 ℃,1 h,70 ℃,15 min。以cDNA为模板,在高保真酶(Q5 High-Fidelity 2×Master Mix)的作用下分段扩增GPGV的核苷酸序列,循环参数为:98 ℃变性30 s,56 ℃退火30 s,72 ℃延伸2 min,35个循环。利用SMARTer® RACE 5'/3' Kit试剂盒扩增GPGV 5'和3'末端序列。PCR产物通过1%琼脂糖凝胶电泳进行检测,琼脂糖凝胶DNA回收试剂盒回收目的片段。纯化后的产物连接至pTOPO-Blunt克隆载体,并转化JM109大肠杆菌感受态细胞,经PCR进行菌液鉴定后,取适量菌液送至华大基因进行测序,剩余菌液用50%甘油保存,置于-80 ℃冰箱备用。

1.5 GPGV基因组序列分析

采用Vector NTI软件将RT-PCR扩增以及cDNA末端快速扩增(RACE)得到的GPGV基因组序列进行组装,获得GPGV的完整基因组序列。利用NCBI ORF finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder)进行ORFs预测,获得GPGV分离物的5'端非编码区(5'-UTR)、3'端非编码区(3'-UTR)和ORFs的序列。利用EMBOSS transeq(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/st/emboss_transeq/)进行ORFs的翻译,获得氨基酸序列。利用Mega 11的ClustalW方法对GPGV在NCBI数据库中所有的完整基因组序列(152个分离物)进行多重序列比对,并以最大似然法(maximum-likelihood method,ML)构建了系统进化树,依MODLES程序确定了建树参数,自展值设为1000。利用BioEdit 7.2软件对完整基因组序列以及ORFs的核苷酸与氨基酸序列进行一致性分析。利用RDP4软件提供的7种重组检测算法对得到的分离物全基因组序列进行重组分析。利用DnaSP v.6.12.03对GPGV分离物进行群体遗传多样性分析[21]。

2 结果与分析

2.1 GPGV内蒙古分离物全基因组序列扩增与基因组结构特征

将葡萄叶片样品提出的总RNA反转录为cDNA后,通过RACE技术和RT-PCR技术扩增出3段重叠的基因组序列以及末端序列(图1)。使用Vector NTI软件将各序列片段进行拼接组装,获得了2条GPGV分离物(20IM-ViVi1和20IM-ViVi2)的完整基因组序列(登录号:OR935780、OR935781)。2条全基因组序列长度均为7250 nt,3'和5'非编码区(UTR)长度为95 nt、82 nt,基因组结构均与已报道的GPGV基因组结构一致,含3个重叠的ORFs,ORF1(96~5563 nt,1855 aa)编码了病毒甲基转移酶(methyltransferases,MT)、2OG-Fe Ⅱ-Oxy加氧酶结构域、病毒RNA解旋酶以及RNA依赖型的RNA聚合酶(RdRp),ORF2(5569~6696 nt,375 aa)和ORF3(6581~7168 nt,195 aa)分别编码了运动蛋白(MP)和外壳蛋白(CP)。

2.2 GPGV分离物序列一致性分析

将所获得的2个内蒙古GPGV分离物与其他GPGV中国分离物进行全基因组序列一致性分析,结果表明,GPGV中国分离物彼此之间的全基因组序列一致率在82.0%~99.9%之间,其中分离物20IM-ViVi1与20IM-ViVi2之间具有较高的全基因组序列一致率,为96.4%(图2)。将所获得的2个序列分别与GenBank中其他GPGV全基因组序列进行成对比对,结果表明,分离物20IM-ViVi1与其他GPGV完整基因组序列的核苷酸序列一致率在79.7%~96.8%之间,其中与俄罗斯白羽分离物Rk3(GenBank登录号:OL961512)之间的全基因组序列一致率最高,为96.9%;与日本紫葛葡萄(Vitis coignetiae)分离物H-JP2(GenBank登录号:LC601812)之间的全基因组序列一致率最低,为78.8%;分离物20IM-ViVi2与其他GPGV完整基因组序列的核苷酸序列一致率在79.5%~97.7%之间,其中与中国夏黑分离物SRR2845691GPGV(GenBank登录号:BK011076)之间的全基因组序列一致率最高,为97.7%;与日本紫葛葡萄分离物H-JP2之间的全基因组序列一致率最低,为79.5%。

为分析GPGV内蒙古分离物分子多样性的具体区域,将所获得的GPGV内蒙古分离物的各ORFs与GenBank中其他GPGV的ORFs进行成对比对,结果表明分离物20IM-ViVi1的RdRp(ORF1)的核苷酸与氨基酸序列一致率的范围分别为78.9%~97.5%、87.6%~98.9%;MP(ORF2)的核苷酸与氨基酸序列一致率的范围分别为80.1%~97.4%、86.6%~98.9%;CP(ORF3)的核苷酸与氨基酸序列一致率的范围分别为84.8%~95.7%、92.3%~100.0%。分离物20IM-ViVi2的RdRp(ORF1)的核苷酸与氨基酸一致率的范围分别为78.6%~97.6%、86.4%~98.7%;MP(ORF2)的核苷酸与氨基酸序列一致率的范围分别为79.9%~98.4%、86.6%~99.2%;CP(ORF3)的核苷酸与氨基酸一致率的范围分别为85.1%~98.1%、92.3%~100.0%。

2.3 GPGV系统进化分析

为明确所获得的GPGV内蒙古分离物与NCBI GenBank数据库已报道的GPGV分离物之间的亲缘关系,利用MEGA11软件以最大似然法构建了系统进化树,MODLES程序判定了最大似然法的最佳进化模型(GTR+G+I)。结果(图3)显示,GPGV现有的152个完整基因组被分为4个分支,第Ⅲ分支和第Ⅳ分支又被分为a、b 2个小的分支。其中本研究中所获得的2个分离物20IM-ViVi1与20IM-ViVi2均聚集在第Ⅰ分支,并均与中国夏黑分离物SRR2845691-GPGV亲缘关系最近。

另外,为明确中国GPGV分离物的系统发育关系,以最大似然法对22个中国GPGV分离物进行了系统发育树的重建,结果(图4)显示,中国分离物主要分为4个分支,其中GPGV新疆分离物Shihezi-1与其他分离物具有较大的遗传距离,亲缘关系较远,被单独分在了第Ⅰ分支。而本研究中所获得的分离物20IM-ViVi1与20IM-ViVi2均被聚集在第Ⅳ分支,并且均与中国夏黑分离物SRR2845691-GPGV亲缘关系最近。

2.4 GPGV的遗传多样性分析

通过DNAsp v.6软件对152个GPGV分离物进行了中性测试以及核苷酸多态性分析,并延ORFs基因组序列走向绘制等比例趋势图。其中中性测试结果(图5)显示,GPGV群体在RdRp、MP以及CP编码区均处的Tajima’s D中性检测值分别为-2.234 92、

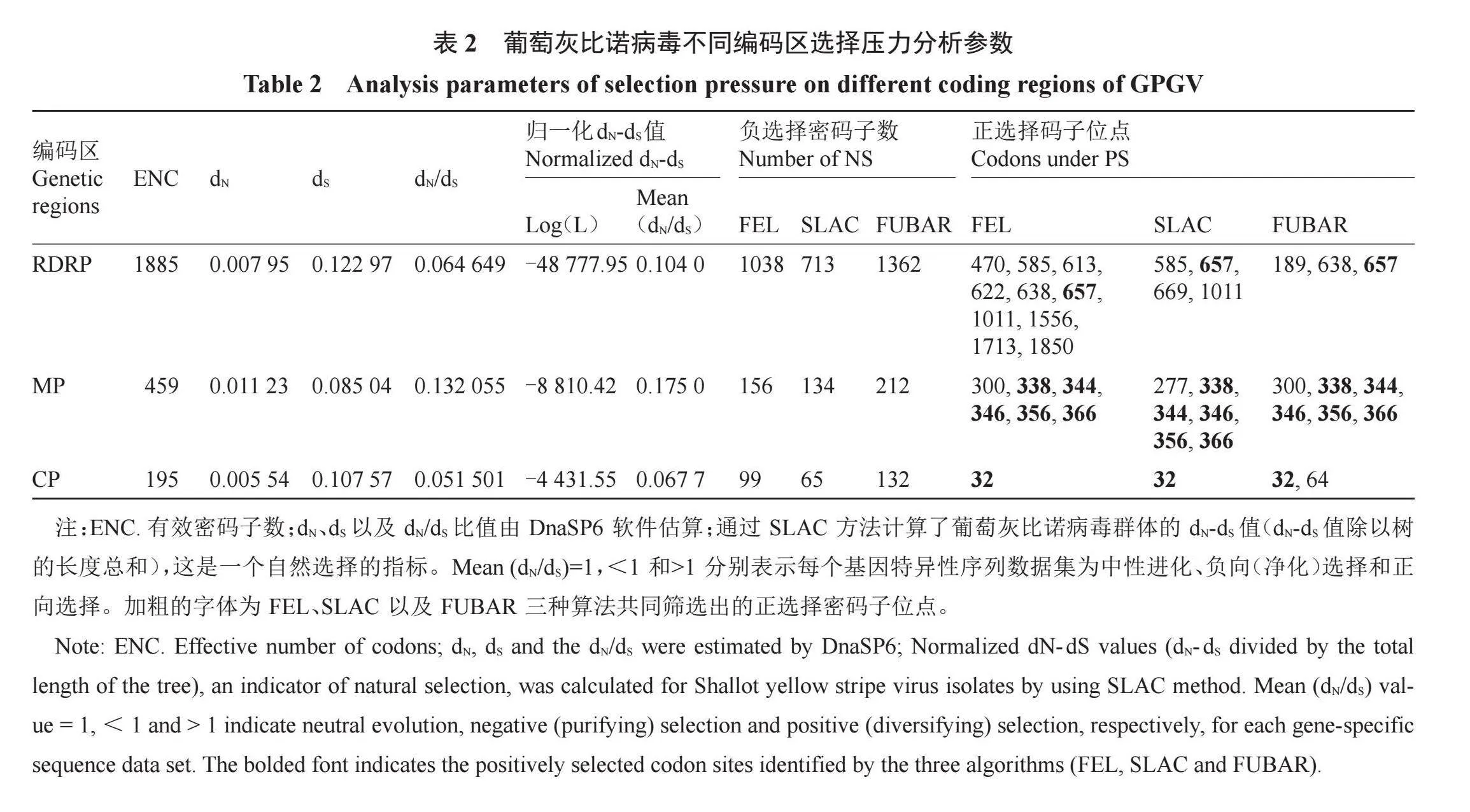

-2.137 45、-2.059 23,且支撑该数值的p值均小于0.05,表明GPGV三个ORFs均受到了显著的负向选择。核苷酸多态性分析结果显示,GPGV群体在RdRp、MP以及CP编码区域的核苷酸多态性(π)为0.032 88±0.001 54、0.028 59±0.003 25、0.028 27±0.004 50,表明GPGV具有较高的遗传多样性。此外,亚洲GPGV分离物的核苷酸多态性(π=0.078 70±0.014 69)显著高于其他大洲GPGV分离物的核苷酸多态性(表2),但亚洲GPGV分离物的中性检测值并不显著,可能遵循中性进化的原则。

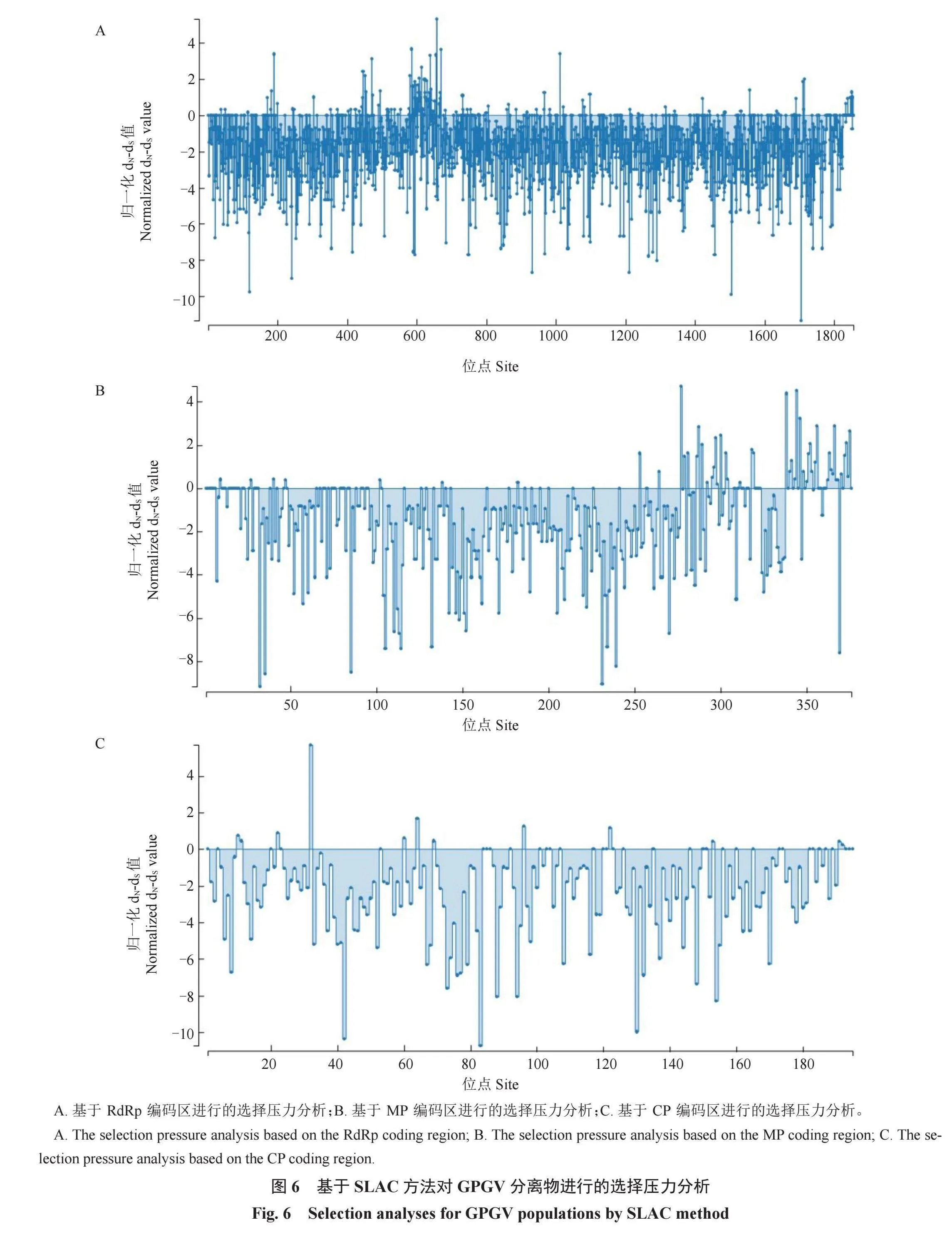

为了评估GPGV进化过程中每个编码区的选择压力变化,使用DNAsp v. 6计算dN/dS比值(表2)。所有GPGV编码区的dN值均小于dS值(dN/dS值<1),表明纯化选择限制了群体的变异性。然而,纯化选择压力在整个基因组中并不是均匀分布的(图6)。CP受到的纯化选择最强,其dN/dS值最低,为0.051 501。MP受到的纯化选择最弱,其dN/dS值最高,为0.132 055。此外,通过使用HyPhy软件包中的SLAC方法进一步表明MP编码区具有较多的正选择位点(图6),且FEL、FUBAR、SLAC三种方法均筛选出了强正选择位点(表2),其中共同被筛选的位点为RdRp编码区的657,MP编码区的388、344、346、356、366以及CP编码区的32。

3 讨 论

GPGV是造成葡萄叶片发病、浆果品质变差的主要病原之一[22-23],前人研究表明在大多数情况下GPGV与葡萄发育迟缓以及叶片发生的褪绿、斑驳、畸形等症状有关[1],而在Saldarelli等[18]的调查中发现GPGV更多的存在于一些几乎无症状的葡萄样品中。Bertazzon等[13]发现有症状的植株的GPGV量高于感染GPGV但无症状的植株。而笔者在本研究中分离得到的GPGV分离物的寄主症状并不相同,考虑到多种病毒复合侵染情况,2个GPGV分离物的致病性有待进一步研究。关于GPGV的草本寄主以及昆虫介体,笔者在本研究中尚未有所收获,然而现有研究表明GPGV还可感染白花蝇子草、藜等草本植物[19],这些草本植物在世界各地的葡萄园中随处可见。这些草本植物中可能会增强病毒的感染繁殖能力、持久性以及扩大传播范围,进而传播给邻近的葡萄[19]。

近年来,GPGV在世界各地越来越多,但是完整基因组序列的报道仍然有限,以至于其起源问题仍然模糊不清,笔者在本研究中对内蒙古7个地区(呼和浩特、包头、赤峰、通辽、巴彦淖尔、鄂尔多斯、乌海)的69个葡萄样本进行多病毒检测时,其中4个地区(呼和浩特、包头、赤峰、通辽)的16个葡萄样本检测出GPGV,检出率高达23.18%,可见GPGV在内蒙古非常流行,对当地葡萄的产量与品质十分不利。因此,笔者在本研究中对感染GPGV的阳性样品进行了全基因组扩增、克隆,得到了2个GPGV内蒙古分离物20IM-ViVi1和20IM-ViVi2的全基因组序列。内蒙古的2个GPGV分离物基因组结构特征与已报道的一致,含3个重叠的开放阅读框(ORF),ORF1编码了病毒甲基转移酶(MT)、2OG-Fe Ⅱ-Oxy加氧酶结构域、病毒RNA解旋酶以及RNA依赖型的RNA聚合酶(RdRp),ORF2和ORF3分别编码了的运动蛋白(MP)和外壳蛋白(CP)[24-28]。

目前,关于GPGV的起源中心研究较多,大多数研究认为GPGV或起源于亚洲,其中Pleško等[12]认为中国极有可能是起源中心。而笔者在本研究中所获得的GPGV分离物20IM-ViVi1和20IM-ViVi2与其他已知的GPGV全基因组序列一致率分别介于79.7%~96.8%、79.5%~97.7%,其中日本紫葛葡萄分离物H-JP2与所获得的分离物序列一致率均为最低,序列变异较大[29],序列相似性分析也证实了这一结果。基于GPGV分离物全基因组序列构建的系统进化树显示,笔者在本研究中所获得的夏黑分离物20IM-ViVi2与南京夏黑分离物SRR2845691-GPGV聚集在同一分支,且亲缘关系最近。在品丽珠、维多利亚、歌海娜以及琼瑶浆等葡萄品种中所克隆到的GPGV全基因组序列也存在近缘关系。因此,寄主差异在一定程度上影响了GPGV的遗传进化,基于GPGV中国分离物重建的系统进化树同样证明了这一点。基于GPGV全基因组序列所构建的系统进化树中还显示出GPGV分离物具有较强的地理特异性,如GPGV中国分离物大多数聚集在第Ⅰ分支,GPGV澳大利亚分离物和意大利分离物大多数聚集在第Ⅲ分支,GPGV法国分离物和加拿大分离物大多数聚集在第Ⅳ分支。基于GPGV中国分离物全基因组序列重建的系统进化树表明,在本研究中所获的分离物与中国东部地区所克隆到的GPGV分离物具有较近的亲缘关系。

物种起源中心通常是其遗传多样性最高的地区[30-31],笔者在本研究中对GPGV进行群体遗传多样性分析,结果表明GPGV亚洲分离物的遗传多样性(π=0.031 95 ±0.001 35)高于其他四大洲的GPGV分离物,因此,亚洲应是GPGV的起源中心。但考虑到基于GPGV全基因组序列所构建的ML树第一节点为日本分离物,Hily等[17]所预测中国是起源地这一观点便不成立。目前,已知的日本分离物有限且变异较大,早期断定的起源时间有待GPGV序列进一步增多后重新分析[17]。Tajima’s D中性测试结果显示,GPGV法国/欧洲分离物受到了显著的负向选择,表明近期GPGV在法国/欧洲发生了种群扩张。

4 结 论

获得了2条GPGV完整基因组序列,分析结果表明,2个GPGV分离物基因组全长为7250 nt,含3个ORFs,与现有GPGV分离物全基因组序列具有较高的一致率(日本分离物H-JP2除外),一致率范围分别为79.7%~96.8%、79.5%~97.7%。此外基于所有GPGV全基因组序列组构建的系统进化树可分为4个分支,本研究所获得的分离物均具聚在第Ⅰ分支。重组分析未发现与本研究所获得分离物相关的重组事件。通过遗传多样性分析发现亚洲GPG分离物具有较高的遗传多样性,或是起源中心,但种群扩张发生在欧洲。本研究可为GPGV分子特征、进化关系以及遗传多样性研究奠定基础。

参考文献 References:

[1] GIAMPETRUZZI A,ROUMI V,ROBERTO R,MALOSSINI U,YOSHIKAWA N,LA NOTTE P,TERLIZZI F,CREDI R,SALDARELLI P. A new grapevine virus discovered by deep sequencing of virus- and viroid-derived small RNAs in cv. Pinot Gris[J]. Virus Research,2012,163(1):262-268.

[2] FUCHS M. Grapevine viruses:A multitude of diverse species with simple but overall poorly adopted management solutions in the vineyard[J]. Journal of Plant Pathology,2020,102(3):643-653.

[3] GOMEZ T S,ALONSO R,LUNA F,LANZA V M,BUSCEMA F. Occurrence of nine grapevine viruses in commercial vineyards of Mendoza,Argentina[J]. Viruses,2023,15(1):177.

[4] BELKINA D,KARPOVA D,POROTIKOVA E,LIFANOV I,VINOGRADOVA S. Grapevine virome of the don ampelographic collection in Russia has concealed five novel viruses[J]. Viruses,2023,15(12):2429.

[5] KAUR K,RINALDO A,LOVELOCK D,RODONI B,CONSTABLE F. The genetic variability of grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV) in Australia[J]. Virology Journal,2023,20(1):211.

[6] TARQUINI G,PAGLIARI L,ERMACORA P,MUSETTI R,FIRRAO G. Trigger and suppression of antiviral defenses by grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV):Novel insights into virus-host interaction[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions,2021,34(9):1010-1023.

[7] BEUVE M,CANDRESSE T,TANNIÈRES M,LEMAIRE O. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV) in grapevine in France[J]. Plant Disease,2015,99(2):293.

[8] REYNARD J S,SCHUMACHER S,MENZEL W,FUCHS J,BOHNERT P,GLASA M,WETZEL T,FUCHS R. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus in german vineyards[J]. Plant Disease,2016,100(12):2545.

[9] GAZEL M,CAGLAYAN K,ELÇI E,ÖZTÜRK L. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus in grapevine in Turkey[J]. Plant Disease,2016,100(3):657.

[10] 夏炎,黄松,武雪莉,刘一琪,王苗苗,宋春晖,白团辉,宋尚伟,庞宏光,焦健,郑先波. 基于宏病毒组测序技术的苹果病毒病鉴定与分析[J]. 园艺学报,2022,49(7):1415-1428.

XIA Yan,HUANG Song,WU Xueli,LIU Yiqi,WANG Miaomiao,SONG Chunhui,BAI Tuanhui,SONG Shangwei,PANG Hongguang,JIAO Jian,ZHENG Xianbo. Identification and analysis of apple viruses diseases based on virome sequencing technology[J]. Acta Horticulturae Sinica,2022,49(7):1415-1428.

[11] RASOOL S,NAZ S,ROWHANI A,GOLINO D A,WESTRICK N M,FARRAR K D,AL RWAHNIH M. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus infecting grapevine in Pakistan[J]. Plant Disease,2017,101(11):1958.

[12] PLEŠKO I M,MARN M V,SELJAK G,ŽEŽLINA I. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus infecting grapevine in Slovenia[J]. Plant Disease,2014,98(7):1014.

[13] BERTAZZON N,FILIPPIN L,FORTE V,ANGELINI E. Grapevine pinot gris virus seems to have recently been introduced to vineyards in Veneto,Italy[J]. Archives of Virology,2016,161(3):711-714.

[14] JO Y,CHOI H,CHO J K,YOON J Y,CHOI S K,CHO W K. In silico approach to reveal viral populations in grapevine cultivar Tannat using transcriptome data[J]. Scientific Reports,2015,5:15841.

[15] GLASA M,PREDAJŇA L,KOMÍNEK P,NAGYOVÁ A,CANDRESSE T,OLMOS A. Molecular characterization of divergent grapevine pinot gris virus isolates and their detection in Slovak and Czech grapevines[J]. Archives of Virology,2014,159(8):2103-2107.

[16] WU Q,HABILI N. The recent importation of grapevine pinot gris virus into Australia[J]. Virus Genes,2017,53(6):935-938.

[17] HILY J M,POULICARD N,CANDRESSE T,VIGNE E,BEUVE M,RENAULT L,VELT A,SPILMONT A S,LEMAIRE O. Datamining,genetic diversity analyses,and phylogeographic reconstructions redefine the worldwide evolutionary history of grapevine pinot gris virus and grapevine berry inner necrosis virus[J]. Phytobiomes Journal,2020,4(2):165-177.

[18] SALDARELLI P,GIAMPETRUZZI A,MORELLI M,MALOSSINI U,PIROLO C,BIANCHEDI P,GUALANDRI V. Genetic variability of grapevine pinot gris virus and its association with grapevine leaf mottling and deformation[J]. Phytopathology,2015,105(4):555-563.

[19] GUALANDRI V,ASQUINI E,BIANCHEDI P,COVELLI L,BRILLI M,MALOSSINI U,BRAGAGNA P,SALDARELLI P,SI-AMMOUR A. Identification of herbaceous hosts of the grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV)[J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology,2017,147(1):21-25.

[20] MALAGNINI V,DE LILLO E,SALDARELLI P,BEBER R,DUSO C,RAIOLA A,ZANOTELLI L,VALENZANO D,GIAMPETRUZZI A,MORELLI M,RATTI C,CAUSIN R,GUALANDRI V. Transmission of grapevine pinot gris virus by Colomerus vitis (Acari:Eriophyidae) to grapevine[J]. Archives of Virology,2016,161(9):2595-2599.

[21] LIBRADO P,ROZAS J. DnaSP v5:a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data[J]. Bioinformatics,2009,25(11):1451-1452.

[22] REYNARD J S,BRODARD J,ZUFFEREY V,RIENTH M,GUGERLI P,SCHUMPP O,BLOUIN A G. Nuances of responses to two sources of grapevine leafroll disease on pinot noir grown in the field for 17 years[J]. Viruses,2022,14(6):1333.

[23] MILJANIĆ V,JAKŠE J,KUNEJ U,RUSJAN D,ŠKVARČ A,ŠTAJNER N. Virome status of preclonal candidates of grapevine varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) from the Slovenian wine-growing region primorska as determined by high-throughput sequencing[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology,2022,13:830866.

[24] BERTAZZON N,FORTE V,FILIPPIN L,CAUSIN R,MAIXNER M,ANGELINI E. Association between genetic variability and titre of Grapevine Pinot Gris virus with disease symptoms[J]. Plant Pathology,2017,66(6):949-959.

[25] 范旭东,张尊平,任芳,胡国君,李正男,董雅凤. 我国灰比诺葡萄病毒分离物检测及基因序列分析[J]. 植物病理学报,2018,48(4):466-473.

FAN Xudong,ZHANG Zunping,REN Fang,HU Guojun,LI Zhengnan,DONG Yafeng. Detection and sequence analyses of grapevine pinot gris virus isolates from China[J]. Acta Phytopathologica Sinica,2018,48(4):466-473.

[26] MURRAY G G R,WANG F,HARRISON E M,PATERSON G K,MATHER A E,HARRIS S R,HOLMES M A,RAMBAUT A,WELCH J J. The effect of genetic structure on molecular dating and tests for temporal signal[J]. Methods in Ecology and Evolution,2016,7(1):80-89.

[27] TARQUINI G,DE AMICIS F,MARTINI M,ERMACORA P,LOI N,MUSETTI R,BIANCHI G L,FIRRAO G. Analysis of new grapevine pinot gris virus (GPGV) isolates from Northeast Italy provides clues to track the evolution of a newly emerging clade[J]. Archives of Virology,2019,164(6):1655-1660.

[28] XIAO H,SHABANIAN M,MCFADDEN-SMITH W,MENG B. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus in commercial grapes in Canada[J]. Plant Disease,2016,100(5):1030.

[29] ABE J,NABESHIMA T. First report of grapevine pinot gris virus in wild grapevines (Vitis coignetiae) in Japan[J]. Journal of Plant Pathology,2021,103(2):725.

[30] VALOUZI H,SHAHMOHAMMADI N,GOLNARAGHI A,MOOSAVI M R,OHSHIMA K. Genetic diversity and evolutionary analyses of potyviruses infecting narcissus in Iran[J]. Journal of Plant Pathology,2022,104(1):237-250.

[31] JONES D R. Plant viruses transmitted by Thrips[J]. European Journal of Plant Pathology,2005,113(2):119-157.