The Irresistible Gardens along Beijing’s Central Axis

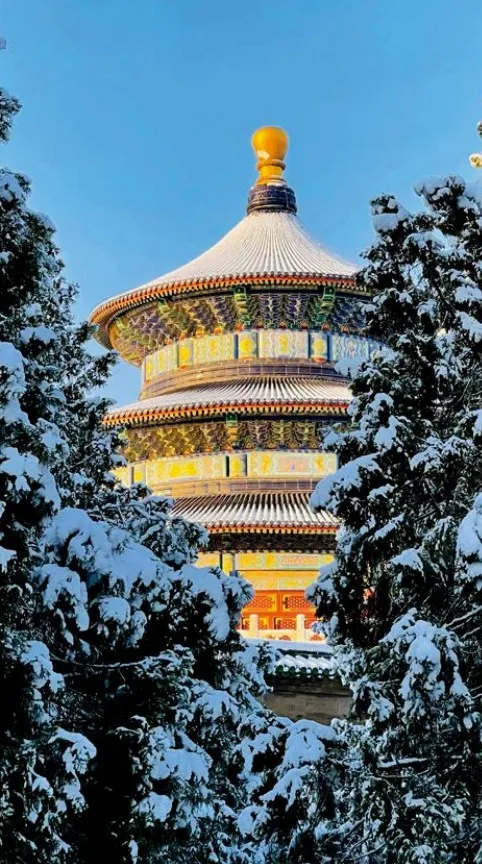

Typically, Chinese gardens make use of the terrain and ingeniously integrate man-made structures such as pavilions, terraces, corridors, and bridges with natural elements such as mountains, waters, forests, rocks, fish, and lotus to form a landscape. Gardens along Beijing’s Central Axis are quite lively and vibrant, which give the area infinite vitality.

The combination of royal palaces and landscape gardens is a basic aesthetic concept of traditional Chinese architecture. From lingtai (astronomical observatories) and lingyou(gardens for emperors to raise and keep animals) in the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 B.C.), to imperial gardens in the Ming(1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties such as the Summer Palace, almost all royal structures embodied this aesthetic concept.

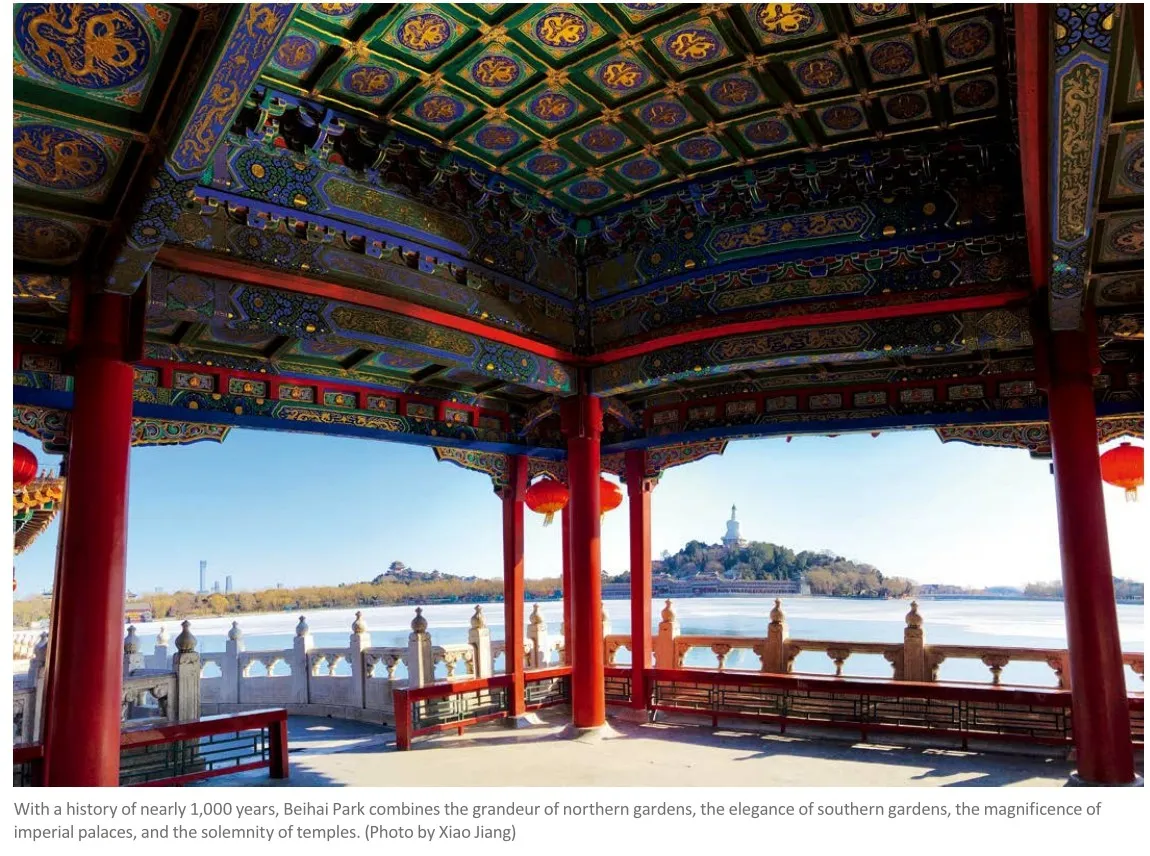

The beauty of the space in classical Chinese gardens has a unique charm compared to palaces and temples. Bringing all the beautiful scenery of the world into one garden was a common practice among ancient Chinese architects and artisans. They imitated natural landscapes or replicated man-made scenery from other places, and then integrated them in imperial gardens along Beijing’s Central Axis, enhancing their timeless aesthetic charm. This holds true for the garden in the Palace of Eternal Longevity and the Imperial Garden in the Forbidden City and Jade Islet in Beihai Park located on Beijing’s Central Axis, as well as those away from the Central Axis like the Summer Palace and Yuanmingyuan Park. For example, the Pool of Great Secretion (Taiyechi), an imperial garden during the Yuan Dynasty(1271-1368), also followed the typical architectural layout popular in the Central Plains region in ancient China, namely, a lake with three islets that represent three legendary islands in Chinese mythology.

China’s profound literary and artistic foundation, heavily influenced by poetry and painting, has nourished the design concepts of the layout and composition of classical gardens. Many poems describing the breathtaking natural scenery of mountains and rivers as well as paintings depicting rivers, valleys, rocks, clouds, and springs are good references for garden architects. Many poets and painters were also directly involved in the design and management of gardens. They focused primarily on natural scenery and utilized elements from nature including mountains, rivers, springs, rocks, flowers, and wild grass. They did not seek luxury or excessive decoration, but instead arranged gardens like poems or paintings to transcend the mundane world. For example, the Half-acre Garden outside the northeast corner of the Palace Museum and the Mustard Seed Garden in the Qianmen area were both designed by Qing Dynasty writer Li Yu(1611-1680).

Luo Zhewen, a renowned Chinese expert in ancient architecture, once expressed his thoughts on the gardening art during the Ming and Qing dynasties. “Ming and Qing gardens no longer pursued a massive size like the primitive gardens and parks that mainly utilized natural landscapes, forests, lakes, ponds, birds, and animals during the Shang(c. 1600-1046 B.C.) and Zhou(1046-256 B.C.) dynasties and also became much smaller compared to the extensive gardens spanning thousands of hectares that were prevalent during the Qin (221-206 B.C.) and Han (202 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties,” he said. “Instead, they evolved towards sophistication and perfection. The relationships between various scenic spots within a garden, as well as scenery inside and outside it, were all arranged organically, elevating the garden to a remarkably high artistic level.”

The gardens along the Central Axis of Beijing provide irrefutable evidence for Luo’s words.