Wang Meng Forever Young

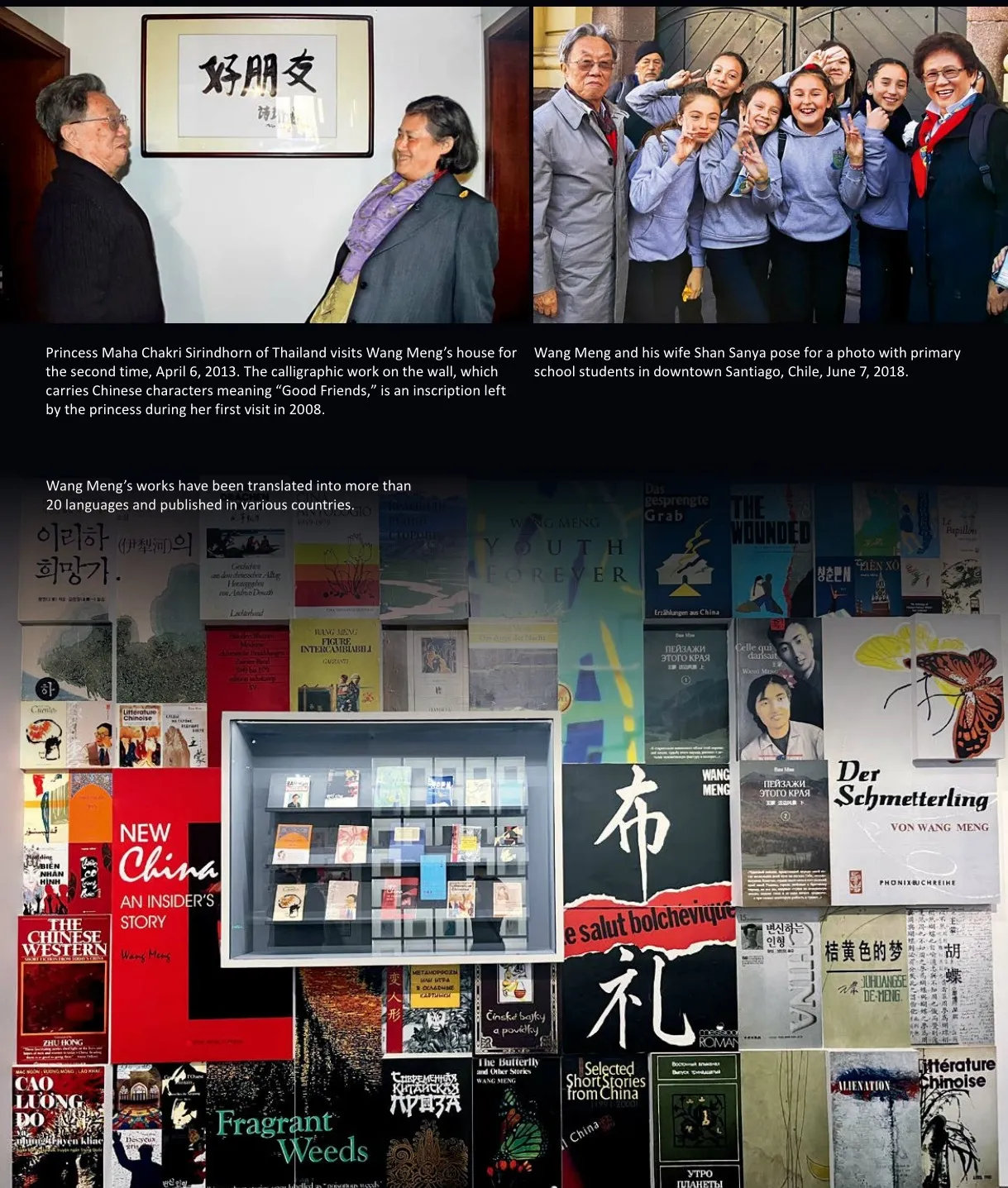

In October 2024, Wang Meng, a famous contemporary Chinese writer, will celebrate his 90th birthday. In 1953, 19-year-old Wang began to write the novel Long Live Youth. Since then, his creative period has been like a never-ending youth. To date, he has published works totaling more than 20 million words, which have been translated into more than 30 languages and published in many countries and regions around the world.

Wang’s literary creation spans throughout the history of contemporary Chinese literature. Rooted in the great changes of modern China, his works highlight a strong sense of the times and have influenced generations of Chinese people. In 2019, he was awarded the national honorary title of the “People’s Artist.” In addition to his literary creations, Wang has also made outstanding achievements in the studies of classical literature and philosophy. He once served as the Minister of Culture of the People’s Republic of China. Through his creative research and eclectic work, Wang has become deeply involved in promoting the development and prosperity of contemporary Chinese literature and culture.

China Pictorial (CP): The novel Long Live Youth, which you wrote when you were oVesYn0lsmouDJd7lwbOXzB2TeQFi9e/hXdAzwcj97Nw=nly 19 years old, has been regarded as a lyrical poem of the youth around the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. How did you begin to use literature to record the youth of that generation?

Wang Meng: Long Live Youth depicts the campus life of female middle school students in Beijing at that time. They were the first generation of youth in New China, full of passion and with a strong sense of romanticism. They were quite amazing.

I was involved in the revolution at a very young age. For me, the revolution carried a kind of youthful romantic sentiment. I was very excited about the founding of the People’s Republic of China, but I also realized that the excitement could not possibly last forever. Around 1952, I began to think about writing down what happened at the time as well as some of my own thoughts. For me, creating Long Live Youth was a way to record and depict those special and passionate days.

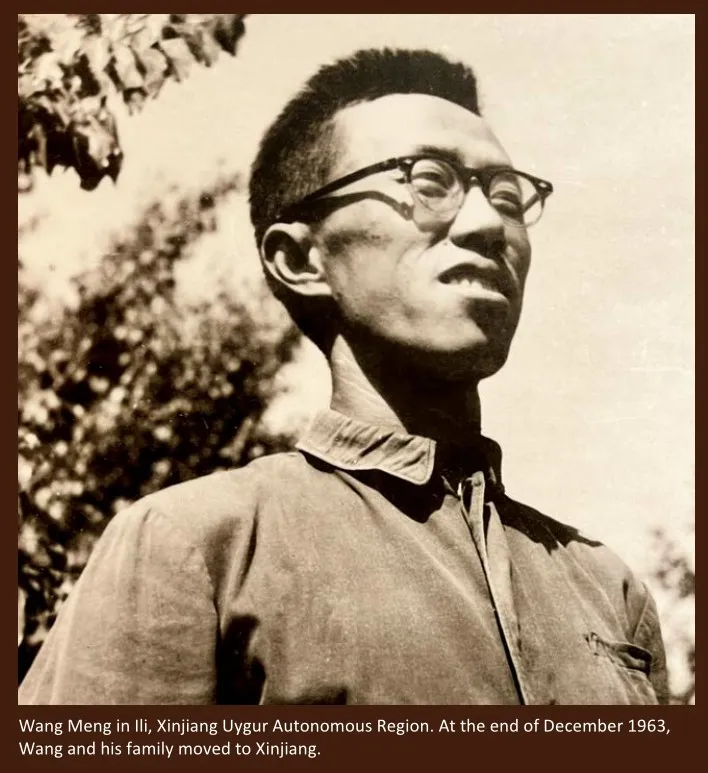

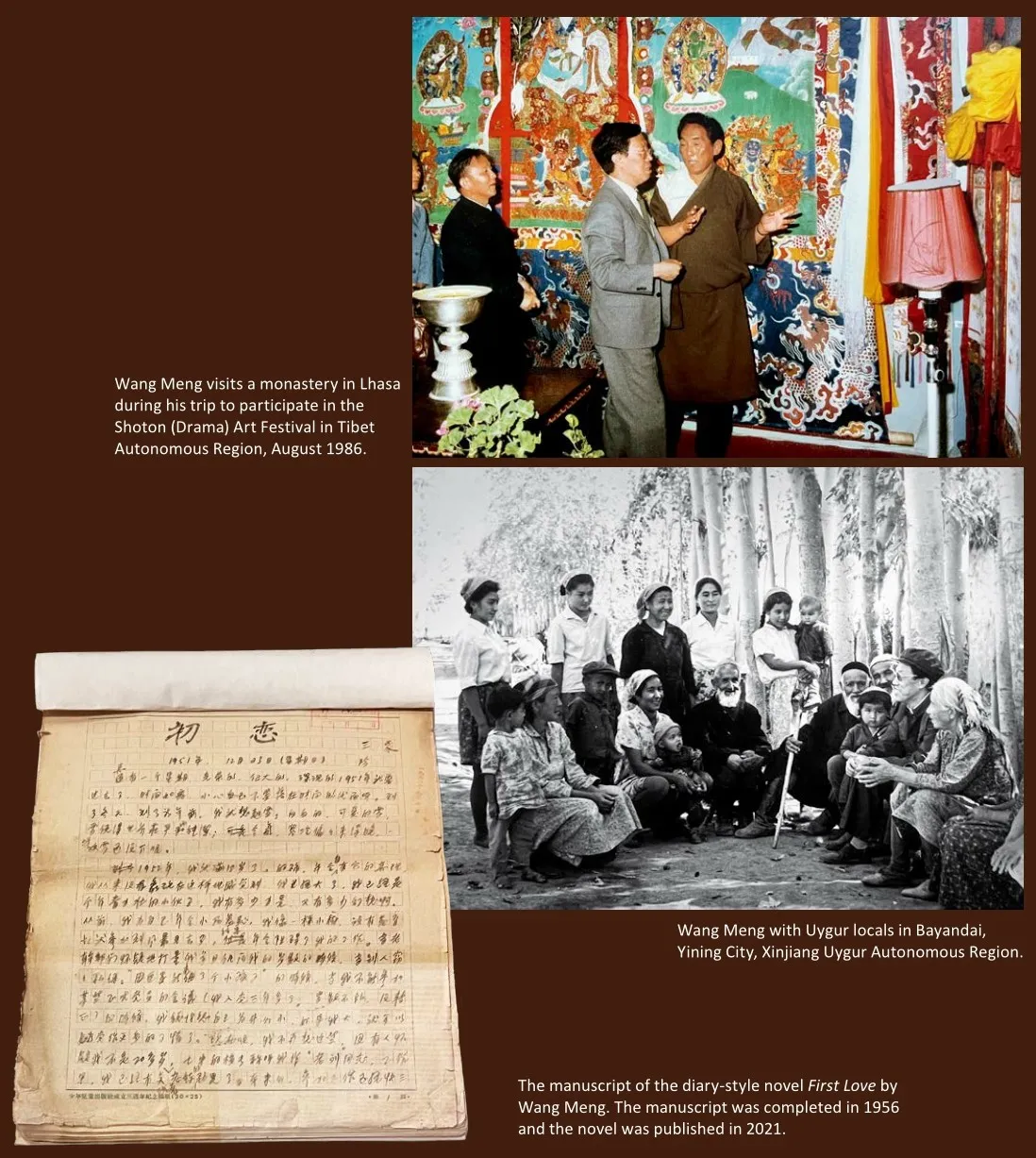

CP: In the 1970s and 1980s, you created many works set in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region including the novel series In Ili and View of This Side. The latter later won the 9th Mao Dun Literature Prize, one of China’s top literature awards. What does Xinjiang mean to you?

Wang: My encounter with Xinjiang was the most important event in my life. One of the main ideas that led me to Xinjiang was that although I was already famous as a writer at that time, I didn’t have much life experience. I hoped to delve into the lives of the people at the grassroots level.

I lived in Xinjiang for 16 years and established deep connections with the locals. In my works, I depicted their weddings, funerals, certain religious ceremonies, their labor processes such as making naan and raising pigeons, and even the bantering between them, all in great detail. For example, in Xinjiang, a special kind of sickles is used to cut grass. The handle is more than one meter long, and the blade is much larger than that of a regular one. Thus, you have to be extremely careful when using it to cut grass, but that labor also brings a kind of joy that cannot be experienced anywhere else.

In 1973, I began working on View of This Side, which was completed in 1978, but the whole text was not published until 2013. It is a great consolation for me that this work was recognized decades later.

CP: After you returned to Beijing from Xinjiang in 1979, you committed yourself to literary innovation and exploration, producing many experimental literary works.

Wang: In fact, I never experiment merely for experimenting. I just have different feelings and impulses when exploring different themes, and I don’t stick to one style. For example, when I describe mental activities in my works, sometimes I write about the process of an event, and sometimes I write about the artistic aura.

Even if an event is not of great significance, it can still touch on certain specific contexts. When a gust of wind blows or snowflakes fall onto your neck, it can trigger a kind of feeling. Suddenly discovering blooming flowers on the road may arouse another kind of feeling. I want to be true to my feelings about life and art, and true to my own heart. People’s minds are different, just like their faces. Innovation is inevitable in literature and life alike.

CP: Do you think that literary and artistic creation still demand human imagination in the internet age?

Wang: Definitely. The value of literature and art lies in the fact that it comes from life and is also the result of the creator’s full imagination, which is almost boundless and infinite.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can absorb large amounts of information and memorize thousands of chess games, so it knows how to deal with any situation when playing chess. It seems to be invincible. However, AI cannot write excellent and touching literary works. The 1941 novella Chess Story by Austrian writer Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) tells the story of a man who is imprisoned for many years for no reason. He spends all day studying chess and finally becomes unbeatable. However, his brain can no longer think of anything else and he ultimately goes crazy. The terminal of AI has already been predicted. AI will become increasingly smarter, but it must stay within existing rules.