歌剧院不眠夜:年轻观众初尝意大利的音乐传承

司马勤

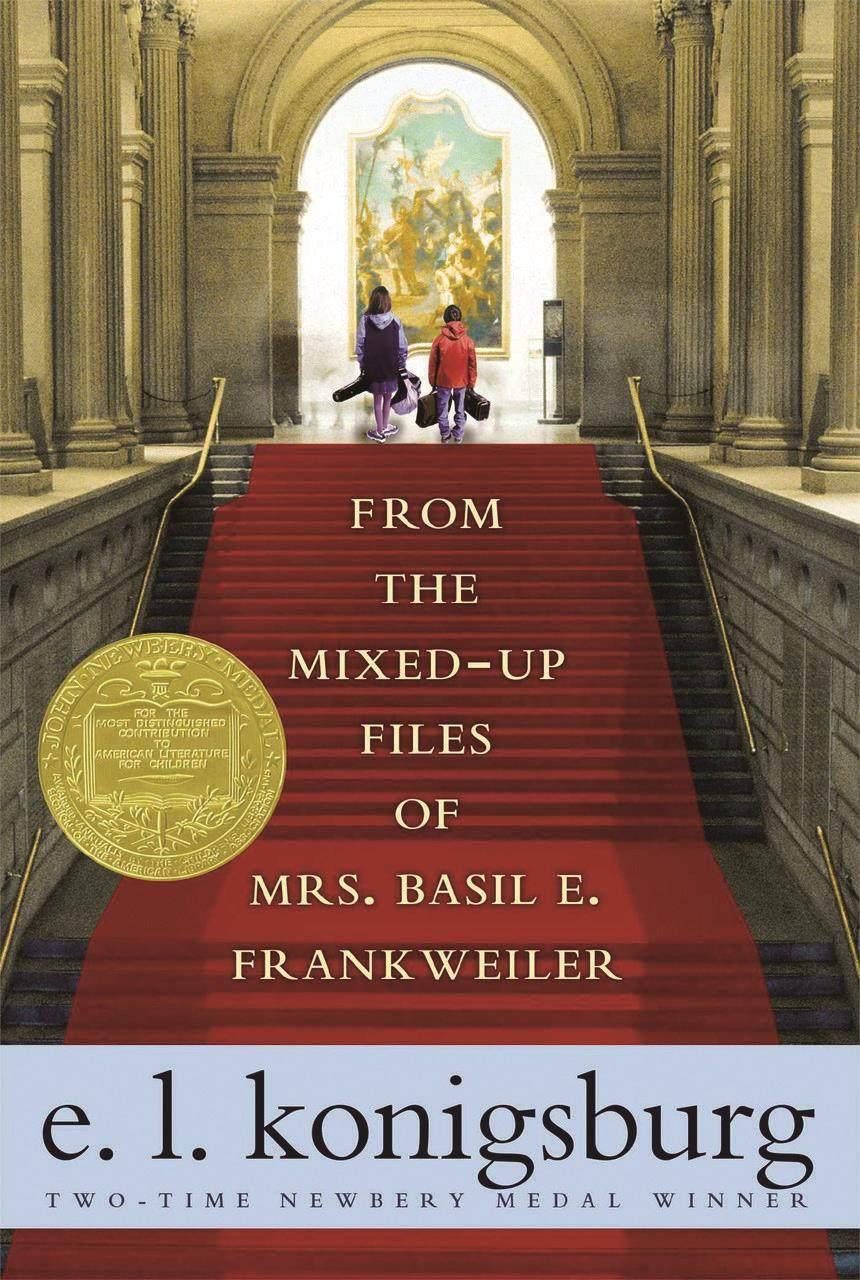

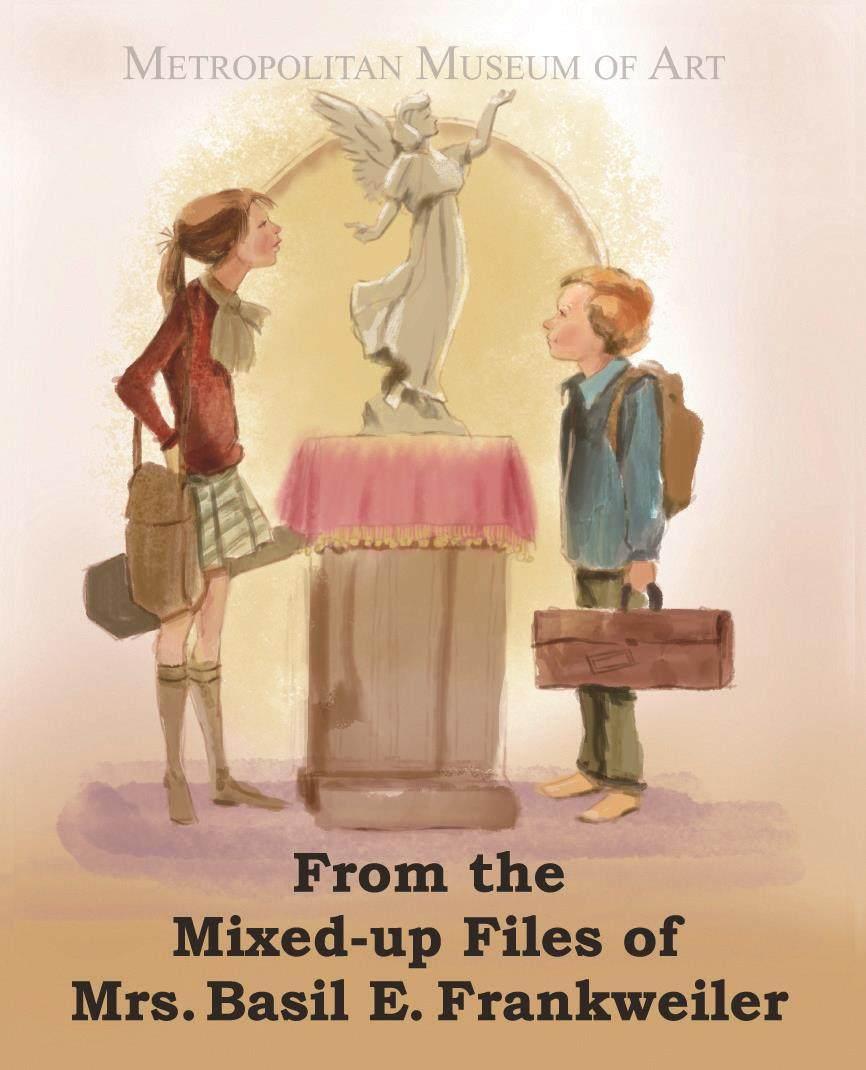

在涉足花天酒地的音乐评论界之前,我在书籍出版社上班。当年我在兰登书屋(Random House)最要好的一位同事得知我对于儿童文学一无所知,觉得很震惊(孩提时代的我很早就开始阅读不少难度高的、成年人看的书籍)。有一天,她送了一本自己小时候最喜欢的书给我:《天使雕像》(这是中文出版时选用的书名,原书名为From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler,直译应为《巴塞尔·E.弗兰克韦勒夫人的乱糟糟的文件摘录》。)

在这个言过其实(还缺乏内容描述性)的标题下,讲述的故事其实相当简单:两个智力超常的顽皮小孩离家出走,躲进了大都会博物馆。到了晚上博物馆关了门,他们把握机会近距离接触珍贵的藏品。书中描述的经历还包括他们在喷水池里洗澡(在池底捡获不少硬币)和睡在博物馆展出的古董大床上。孩子们顺便破解了一宗专家们一直以来被蒙在鼓里的艺术赝品案件。

故事也涉及很多其他的情节,但言归正传,这本儿童小说已经成为经典,赢得了多项大奖,并跨越了媒体,被改编为不同的电影、电视版本(这部作品的成功大概也可以归功于系列电影《博物馆奇妙夜》,尽管这部电影的取景地是另一类型的博物馆)。如果我没记错的话,《天使雕像》一书中更附上了大都会博物馆的地图指南,这使它成为博物馆有史以来最成功的商业广告之一——对不起,应该用“观众拓展”这个词。对于大都会博物馆来说,这本书为博物馆带来前所未有的曝光率。

不过,有时你遇上经典时会相逢恨晚。在我20岁出头的时候,唯一感兴趣的“大都会”不是博物馆,而是歌剧院。当时就已经流传过不少报道,说美国的歌剧观众群以老年人为主,且平均年龄还在不断上升。因此,每当我坐进大都会歌剧院观众席,就会感觉当时的自己将观众平均年龄拉低了至少10岁。当年那个神圣的音乐殿堂虽然敞开大门,却没有提供任何吸引年轻一代的东西——就算有,那些观演体验也绝对说不上亲善友好。

因此,除了观看那些利用很少美国人熟悉的语言写出来的老戏宝,除了跟着那些对于歌剧艺术已经了如指掌的老人在一起观剧,如果小孩子有机会能在歌剧院关门后进入那里探险,甚至可以试试服装、摸摸道具,按照自己的方式构建出一个幻想国度,又会发生什么呢?

我可以很肯定地说,这种设想在大都会歌剧院是永远不可能发生的:这家歌剧院在纽约市立歌剧院引进投影字幕十年后才追上了潮流。对于构建一个真正能供孩童体验的歌剧院项目,这种前瞻性思维必须发散得更远。

第一个宣称“条条大路通罗马”(All roads lead to Rome)的并非意大利人。严格来讲,意大利这个国家在公元1175年,即法国教士阿兰·迪·里尔(Alain de Lille)首次把这个概念记录下来的年份,还未建国。里尔当年用拉丁文这样写道:mile viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam,即“一千条路永远把人们引向罗马”(杰弗里·乔叟是第一个用英语表达同一个理念的人,但他的文句更为复杂)。后来这一概念浓缩成精简的短句,更为朗朗上口。

几个世纪以来,罗马一直是美食家的天堂,当然也以古代历史和歌剧闻名。这个城市通常不提供的——尤其是因为在过去76年里经历过68届政府,就是在当地为其他人解决他们的问题。

然而,罗马这个名字最近从四面八方浮现出来。5月,戛纳电影节刚呈献了两部刻意令人联想到罗马的影片——亚当·德赖弗在法兰西斯·科波拉编导的《大都会》(Megalopolis)中饰演一个名为“恺撒”的角色;克里斯·海姆斯沃斯在乔治·米勒的电影《疯狂的麦克斯:狂暴女神》(Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga)中出演的人物(据《纽约时报》的描述,他像个“重金属的战车御者”)。在公共事务的范畴,纽约州、马萨诸塞州与加利福尼亚州的州长参加了由罗马教皇方济各主办的气候变化峰会;此前一周,纽约市市长埃里克·亚当斯也到访罗马,考察当地处理近期移民大量涌入危机的应对措施(可想而知,移民与右派反移民势力的冲突几年前已在罗马发生,后来世界各地才纷纷效仿)。

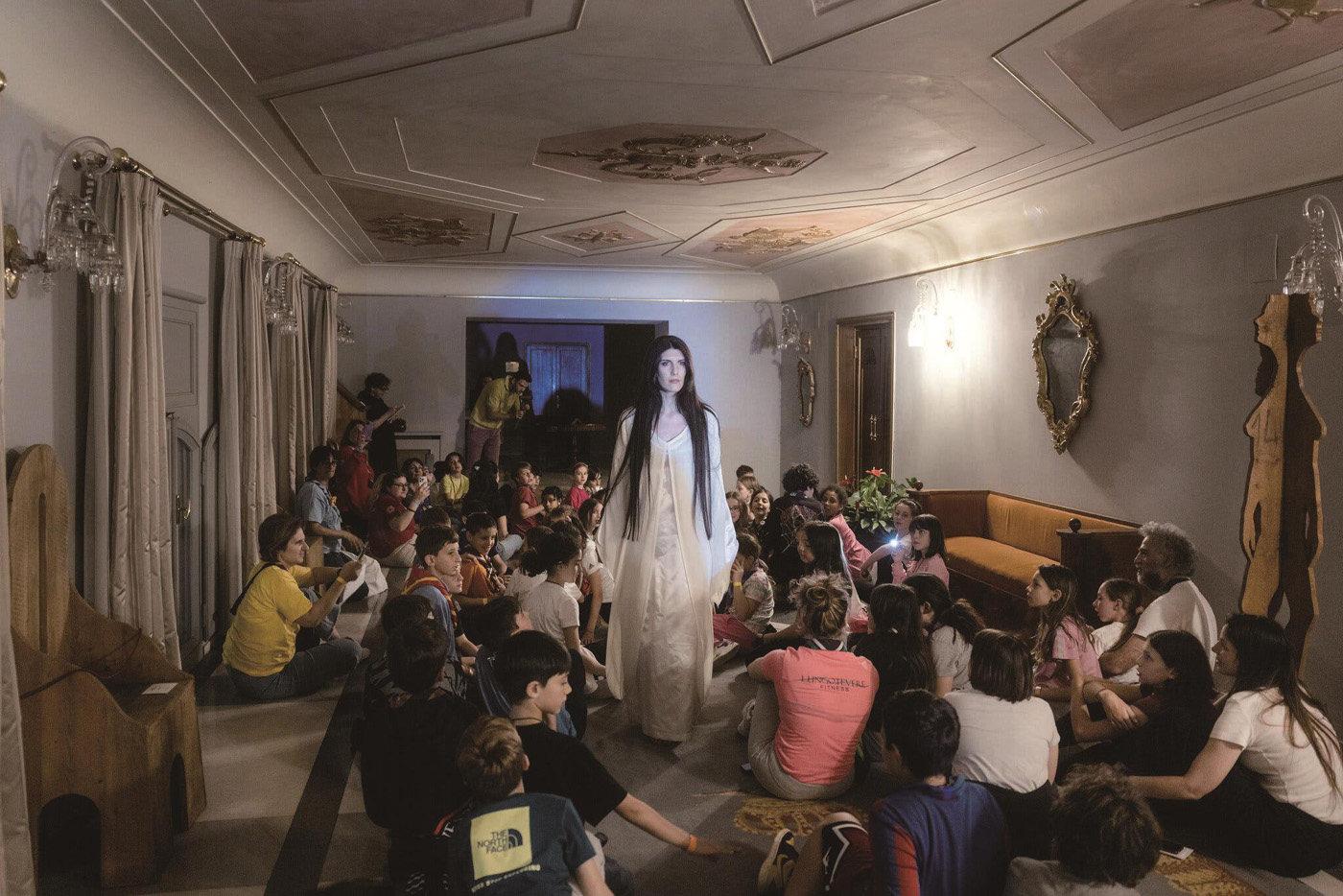

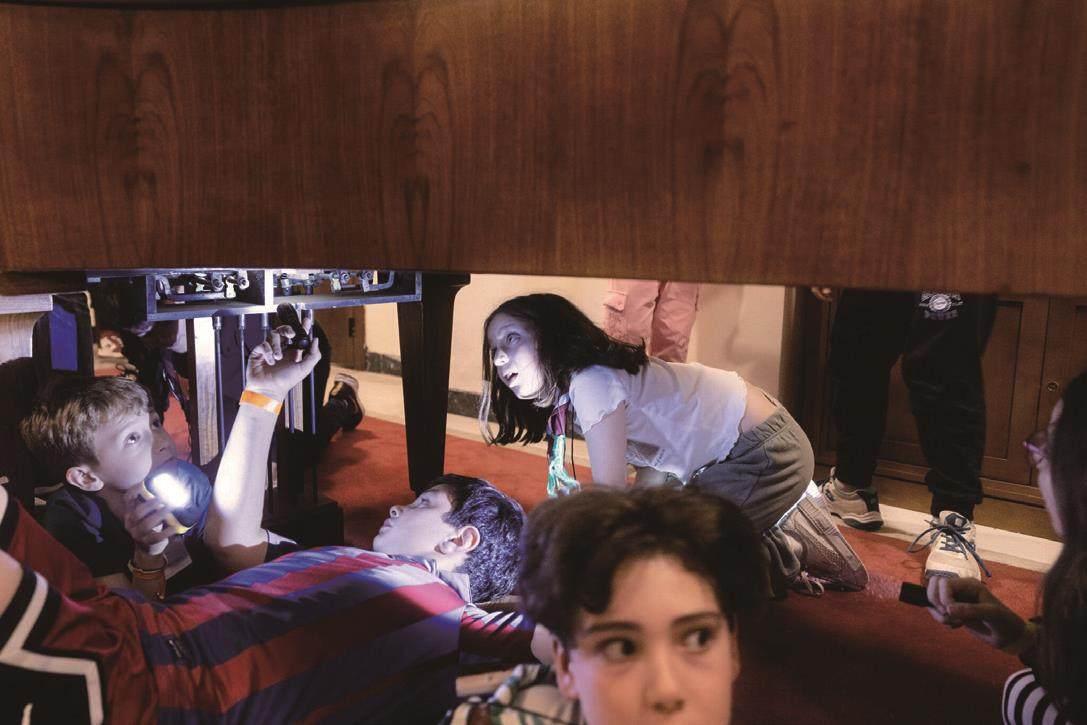

因此,当我听说罗马歌剧院的驻地——科斯坦齐剧院(Teatro Costanzi)刚刚邀请了130名8至10岁的儿童在那里留宿一晚的消息后,我一点都不惊讶。除了观看乐团排练、学习基本芭蕾舞步、有机会一起参加合唱、用纸张制作戏服外,这些孩子们还亲眼看到剧院维修工人如何清洗全世界最大的水晶灯。他们更遇上一个“鬼魂”——一百年前,女高音艾玛·卡利里(Emma Carelli)接管了剧院经理一职,并在这里工作多年,有传言说“她”仍会在剧院的各个走廊出现(扮演艾玛的女高音是罗马歌剧院青年艺术家计划的成员;后来她刻意卸了妆,以素颜真面目跟儿童访客们再次会面,以确保孩子们不会信以为真而被吓到)。

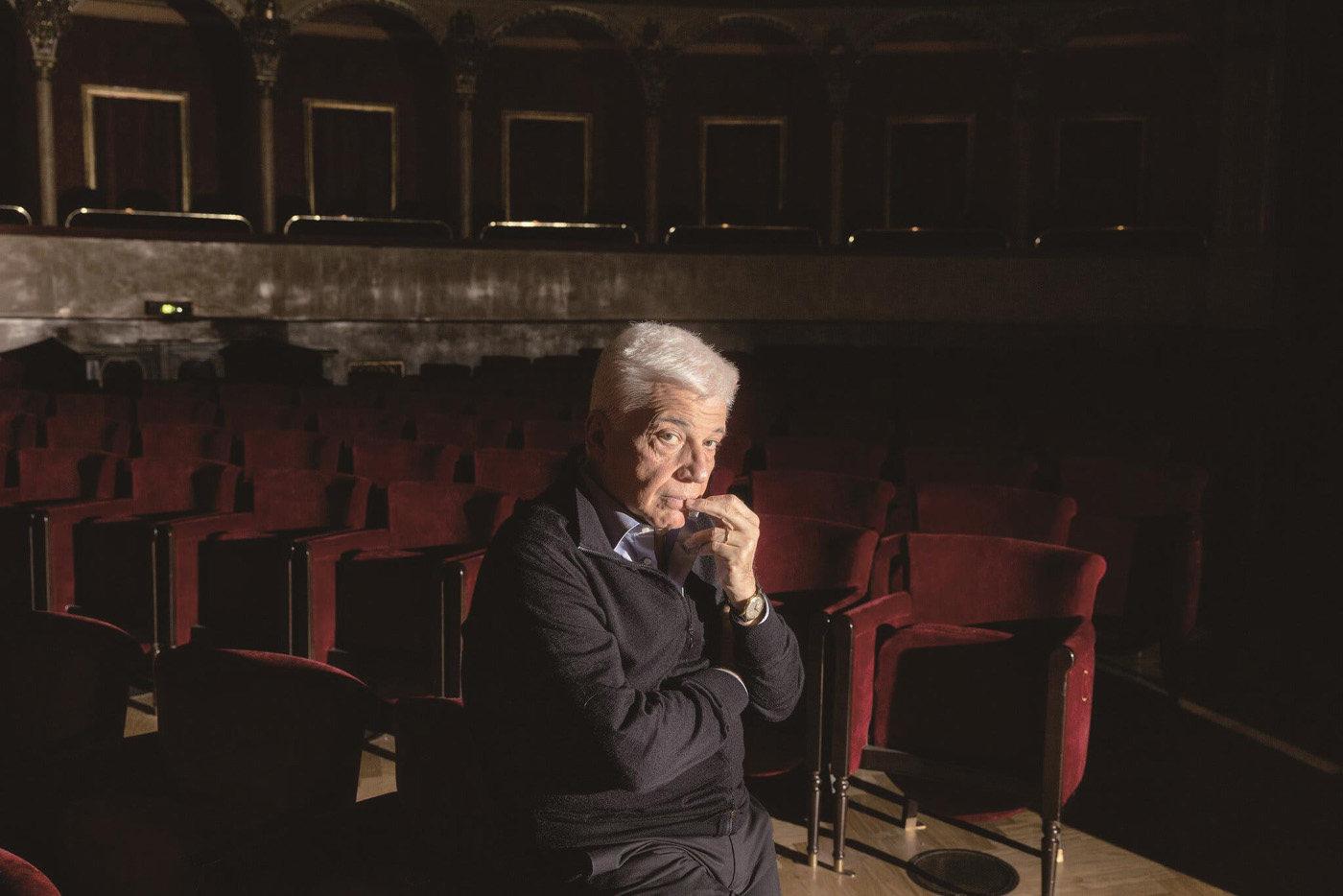

孩子们在参加了寻宝游戏之后,熟悉了剧院前后台的各个角落。这不但是大部分参加者首次造访歌剧院——其中许多人都来自比较贫穷的家庭——当家长送孩子到罗马歌剧院时,也是他们首次踏足这个艺术场馆。“我们深信剧院应该服务全民,”科斯坦齐剧院总经理弗朗西斯科·吉安布朗尼(Francesco Giambrone)接受《纽约时报》访问时说,“进入到我们剧院的每一个人都应该觉得宾至如归。”

从我记事起,美国与英国的国民一直都会哀叹自己国家的教育政策里没有兼顾音乐教育,资源不足。然而很多观察人士却指出,英美的音乐教育情况比意大利幸运得多:意大利的某些政客时而沉浸在自己国家歌剧悠久传承的荣誉感中,时而又会有不少人强烈谴责这门艺术是社会阶层战斗的遗物。

其实,反讽的意味十分明显:意大利是歌剧的发源地,但这个国家的议会议员不仅经常对音乐教育投反对票,他们更拒绝认可歌剧为意大利国宝(可是,意大利还是成功地将“歌剧歌唱艺术”列进联合国教科文组织人类非物质文化遗产代表作名录)。

作为一种自我保护的手段,全球的专业艺术机构都致力于举办艺术教育项目。美国很多大城市都发起了“辅助”艺术教育项目,而意大利起步较晚,到现在也没追得上,但后者却有更深厚的艺术根基资源可以使用。罗马歌剧院除了积极拓展年轻观众以外,更针对无家可归者与住在偏远地区的人们安排了不同项目。这家歌剧院早在1990年代就设立了教育项目,其本意是为了拓展市场。歌剧院方面充满信心地表示,多年前参与过歌剧院教育活动的青年人如今仍是歌剧院忠实的观众。

至于意大利歌剧传承的问题,今天的艺术家、艺术管理人员与高瞻远瞩的政策制订者可能会感到一丝安慰:即使在19世纪歌剧艺术最巅峰的全盛时期,一位声名显赫的、精通音乐的意大利国会议员曾经游说过国会支持公立学校开办音乐教育课程,可是他没有成功。

他的名字是——朱塞佩·威尔第。

Back when I worked in book publishing, right before I joined the music criticism racket, a close colleague at Random House was appalled at how little I knew about childrens literature. (Even as a child, I went straight to the hard stuff.) One day she presented me with her favorite book from childhood: From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

Inside that overblown (and not terribly descriptive) title was a pretty simple premise: two precocious kids run away from home and sneak into the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they camp out and experience the exhibits after hours. This includes bathing in the fountain (snagging the coins from the bottom) and sleeping the museums antique beds. They also wind up solving a case of a counterfeit exhibit that had fooled the experts.

Theres more to the story, but to get to the point, the book had become a classic, winning numerous awards and spawning film and TV adaptations. (It probably also had something to do with Night at the Museum, despite that film taking place at a very different museum on the other side of town.) If I remember correctly, the book even contained walking maps of the Met, which made it one of the most successful commercial advertisements—sorry, I mean tools for audience outreach—that a museum had ever seen.

Sometimes, though, you discover a classic too late. In my 20s, the only Met I was interested in was the Metropolitan Opera. Much was made at the time about how opera audiences in America were old and growing older. My very presence in the house seemed to lower the average age by at least a decade. Very little was there to entice a younger generation to enter those hallowed doors—and even if there was, the experience wasnt exactly welcoming.

So instead of seeing old shows in languages that few Americans spoke well, with older audiences who seemed to know everything, what would happen if kids had the chance to enter the opera house after hours, in full reach of costumes and props and able to enter a fantasy world on their own terms?

I think its safe to say that would never happen at the Met, an opera company that was still resisting surtitles a decade after theyd become a mainstay at New York City Opera. For a truly forward-thinking childhood experience, youd have to go back a bit further.

The first guy who claimed that “All roads lead to Rome” wasnt actually Italian. Strictly speaking, Italy didnt even exist as a country in 1175 when the French cleric Alain de Lille first penned mile viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam, literally “a thousand roads forever lead men to Rome.” (Geoffrey Chaucer, who first expressed the same sentiment in English, was even more verbally cumbersome.) But boiled down to five words, the phrase continues to roll off the tongue.

For centuries, Rome has been a destination for fine dining, communing with ancient history and, of course, opera. What the city has not generally offered, particularly with its 68 different governments in 76 years, are solutions for other peoples problems at home.

And yet, Rome has been popping up lately from every direction. Two films at the Cannes Film Festival in May were cited for consciously referencing ancient Rome (Adam Driver playing a character named“Cesar” in Francis Ford Coppolas Megalopolis; Chris Hemsworth mimicking “a heavy-metal charioteer,” to quote the New York Times, in George Millers Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga). In the public sector, the governors of New York, Massachusetts and California joined in a summit on climate change hosted by Pope Francis only a week or so after New York City Mayor Eric Adams came to Rome looking for solutions in how to handle the citys recent influx of migrants (as with so many other things, migrants and right-wing antiimmigration blowback surfaced in Rome before it became fashionable).

So I guess I shouldnt be surprised that Teatro Costanzi, the home of the Rome Opera, recently hosted a sleepover for nearly 130 children, ages 8 to 10. In addition to watching the orchestra rehearse, they learned basic ballet moves, sang in a chorus, made costumes out of paper, and discovered how the buildings maintenance staff cleans the worlds largest chandelier. There was also a cameo visit by a ghost—the spirit of Emma Carelli,a soprano turned theatre manager from a century ago who is still rumored to be haunting the halls.(The singer from the companys young artists program later reappeared without makeup, just in case some of the audience thought that “Emma”was real.)

After participating in an organized treasure hunt, the kids learned many of the theatres nooks and crannies. It wasnt just the first time in the opera house for most of the participants—many of whom came from disadvantaged backgrounds—but also for many of the parents who dropped their children off for the night. “We believe that the theatre should be for everyone,” the Costanzis general manager Francesco Giambrone told the New York Times, “and that it should make people feel at home.”

For as long as I can remember, people in the United States and England have lamented the state of their respective countrys music education. Many observers, though, have pointed out that the problem in those countries is not nearly as pronounced as it is in Italy, where politicians veer between basking vi- cariously in the countrys operatic heritage and condemning the current art form as a socially stratified battleground in the class wars.

You dont need to look far to see the irony: lawmakers in the country that invented opera not only regularly vote against supporting music education but have also refused to declare opera a national treasure. (Italy did, however, successfully campaign to have opera singing included in UNESCOs Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.)

As a means of self-preservation, arts education around the world now falls largely to the professional organizations themselves. Italy may not have been as quick to develop supplemental arts education as some of the major cities in the US, but they have much deeper roots to draw on. In addition to its work with young audiences, the Rome Opera also has programs for the homeless and those who live in geographically challenged areas. The company organizes its educational programs—many dating back to the 1990s—under the general banner of marketing, and one thing the company says with complete confi- dence is that many of those young participants from years ago remain loyal operagoers today.

As far as Italys operatic heritage is concerned, todays artists, artistic administrators and forwardthinking lawmakers can take cold comfort in that fact that even during operas heyday in the 19th century a prominent music-conscious member of Italys Parliament was unable to convince his fellow lawmakers to support music education in the nations public schools.

His name was Giuseppe Verdi.