社会等级的进阶路径及其演化:来自比较研究的启示

郑明璐 刘林澍 叶浩生

摘 要 社会等级是一个动态演化的多维系统, 其获取可分为三大路径。支配路径强调借助攻击与威胁获取资源, 在激烈的性选择压力下演化而来。能力路径突出知识/技能对获取地位的作用, 源于技术性觅食所产生的文化学习需要。与前两种路径不同, 以心理利他为特征的美德路径为人类社会所独有。它是文化演化的产物, 其存在是为了解决大规模集体行动的问题。三种路径在存在范围、行为模式和结果、演化动因以及情感介质等方面存在差异。未来研究可进一步澄清不同动物群体性选择模式与支配等级的关系, 结合多个学科考察人类能力路径演化的特殊环境, 并探究美德路径的生物性基础。

关键词 社会等级, 支配路径, 能力路径, 美德路径, 演化成因

分类号 B849: C91

1 引言

在动物社群结构的研究中, “社会等级”概念意指个体依据影响力大小在群体内所获得的相对位置, 有时也被称作地位等级或社会地位(Bai, 2017; Chen et al., 2012)。它源自挪威科学家Schjelderup-Ebbe (1922)在研究家禽社会行为时提出的“啄序” (pecking order)概念, 随后演变为“支配等级” (dominance hierarchy)。然而支配这一单一维度不足以描述人类社会等级系统的复杂性, 因而学界最终形成的“社会等级”概念指包含支配等级在内的各种等级系统(Redhead & Power, 2022)。从宏观角度看, 这些不同的系统就构成了社会等级的维度(或标准); 从微观角度看, 它们又是个体提升社会等级的路径。先前研究探索了种群内社会等级的静态特征, 但关于人类社会的多维等级系统如何演化而来, 以及它与动物的等级系统有何区别, 目前所知甚少。基于此, 本文尝试从演化视角系统梳理社会等级相关理论与研究, 比较动物和人类社会等级系统异同点, 以期揭示社会等级从单维到多维的迭代过程, 并探讨其背

后的演化动因和条件。

2 支配路径

动物群体中等级是由什么决定的?在Schjelderup-Ebbe (1922)的研究中, 一开始家禽(母鸡)为了争食频繁互相攻击, 过了一段时间, 攻击行为逐渐减少, 进食行为变得有序。研究者推测, 每一只母鸡都记住了与其他母鸡竞争的胜败经历——群体建立了某种等级秩序。所以, 在冲突对抗中借助攻击和威胁等手段令其他群体成员产生恐惧, 从而在资源竞争中获胜是动物提升社会等级最重要的手段, 这就是支配路径(Griskevicius et al., 2009)。但支配并不等同于攻击, 攻击只是获取支配地位的一種手段。那些阻碍他人达成目的的个体也被知觉为具有支配性(Krupenye & Hare, 2018; Terrizzi et al., 2020), 因为这些个体掌控着重要资源, 能够借助资源剥夺威胁来唤起从属者的恐惧, 从而在竞争中占据优势(Tracy et al., 2020)。

总之, 借助攻击和威胁, 群体便可建立起等级秩序。通过准确评估同类的支配等级, 个体便可在冲突情况下做出最佳行为决策, 无需每次竞争都诉诸武力。也就是说, 动物借助攻击所建立起来的等级, 其目的恰恰是要减少攻击行为(Murlanova et al., 2022)。

2.1 支配路径的存在范围

支配路径能够有效减少群体内冲突, 以相对较小的代价实现资源分配, 因此包括灵长类在内的绝大多数群居动物都存在支配等级(Boucherie et al., 2022; Grosenick et al., 2007; Shizuka & McDonald, 2015)。目前学界已开发了多种手段检测动物间的支配关系。田野研究通常记录动物在自然状态下攻击?服从(aggression-submission)的行为指标, 比如理毛、求偶、追逐、爬跨等; 实验研究一般采用进取?退让(approach-retreat)资源竞争范式, 具体任务包括食物争夺、领地标记以及路权博弈等(Fan et al., 2019; Murlanova et al., 2022; Wooddell et al., 2020)。虽然人类演化出了高度的亲社会性及社会规范性, 能够在一定程度上抑制支配行为, 但无论在实验情境还是现实生活中, 霸凌、粗暴、贬损以及其他反社会行为依然能帮助个体在群体中赢得地位(Thomas et al., 2018; van der Ploeg et al., 2020)。

近年来, 随着光遗传等神经操纵技术的开发与应用, 越来越多的研究者从神经层面探索支配行为的脑机制。尽管社会等级的神经回路涉及多个脑区, 但有证据表明, 内侧前额叶皮层(medial prefrontal cortex, mPFC)可能是这一调节机制的核心区域所在。它能够编码竞争行为, 表征支配等级, 并预测未来竞争胜败(Ligneul et al., 2016; Padilla-Coreano et al., 2022 ; Zhou et al., 2017)。当支配等级变得不稳定时, 向上比较不仅会激活mPFC以追踪等级变化, 杏仁核(amygdala)也会被激活(Jiang et al., 2023; Zink et al., 2008), 诱发个体通过观察学习形成恐惧性条件反射(Munuera et al., 2018), 而支配路径正是以恐惧为情感介质。因此可知, 动物通过两种方式表征支配等级:一是在直接的二元对抗中, 通过试误(trial-and-error)方式, 即强化学习的方式; 二是通过观察群体中其他成员之间的互动, 即通过观察条件反射(Federspiel et al., 2019)。因此, 行为层面和神经层面的研究都表明, 支配等级在群居动物中普遍存在。

2.2 支配路径的演化成因

尽管支配等级能给群体带来诸多好处, 比如加强群体社会联系和稳定性(Levy et al., 2020)、对搭便车行为实施惩罚(Lukaszewski et al., 2016), 但雄性同性竞争可能是支配路径产生的主要选择压力。根据Trivers (1972)的亲代投资和性选择理论, 雌性无法通过与更多雄性交配来增加后代数量, 因而会花更多时间在照顾后代上; 相反, 雄性可通过增加配偶数量来提高繁殖成功率, 它们会花更多时间在同性竞争上, 这导致雄性间择偶竞争变得激烈。“挑战假说” (the challenge hypothesis)进一步指出, 当雌性处于繁殖期时, 雄性的睾酮水平急剧升高, 表现出更高的攻击水平, 从而在“择偶市场”占据优势(Carre & Archer, 2018)。因此, 绝大多数对支配地位的研究集中在雄性动物上。从啮齿动物(Murlanova et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2011)到非人灵长类(Muniz et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2019)的研究都表明, 支配地位能有效解释雄性间繁殖成功率的差异。

Leimar和Bshary (2022)采用演化博弈法研究支配等级形成机制, 发现支配地位与战斗能力呈正相关。由于雄性间的这种等级竞争通常是暴力且致命的, 因此, 战斗前的预评估所带来的好处就会形成一种压力, 使物种演化出自身战斗能力的外部信号(Winegard et al., 2014)。尽管武器、技巧、激素、脂肪储备等都会影响个体战斗水平(Tibbetts et al., 2022), 但体型通常被认为是战斗能力最直接、最准确的外显指标(Couchoux et al., 2021; Reddon et al., 2011)。因此, 大量研究發现体型能很好地预测雄性支配地位及繁殖成功率(Cassini, 2019; Montana et al., 2022; Wong & Balshine, 2011)。

雄性借助体型来竞争支配地位, 使得雌雄体型产生差异, 这被称作性别体型二态性(Sexual size dimorphism, SSD)。尽管SSD也受到其他一些因素(如资源竞争、雌性选择等)影响, 但如果一个物种表现出非常强的雄性偏态体型二态性, 那往往意味着该物种实行多偶制并伴有激烈的雄性同性竞争(Plavcan, 2012)。在现存灵长类中, 大猩猩雌雄体型差异最大, 它们实行一夫多妻制, 雄性体型大小与雌性配偶的数量呈正相关(Breuer et al., 2012)。最早出现于4百多万年前的人科动物南方古猿(Australopithecus), 其雌雄体型差异接近甚至超过大猩猩, 这表明它们也实行多偶制并伴有激烈的雄性身体对抗(King, 2022; Puts, 2010)。

总而言之, 支配路径是当前等级研究中最受关注的一个领域。现有研究表明, 雄性之间为争夺配偶展开的激烈同性竞争可能是支配路径的主要演化动因, 其表现就是雄性为了争夺支配地位而不断强化体型优势, 最终造成雌雄体型二态性。在性选择基础上建立起来的支配等级可能在随后被迁移到其他资源的分配中。脑机制研究进一步揭示了支配路径演化的神经物质基础:内侧前额叶皮层被认为是支配行为的决策中枢, 激活或者抑制该脑区能改变动物在等级冲突中的攻击/退让选择; 杏仁核可能是支配行为的情绪中枢, 它与通过观察学习形成恐惧性条件反射有关。

3 能力路径

然而, 一些研究者对支配路径理论提出了质疑。人类社会存在大量合作以完成复杂任务。在任务导向的群体中, 以支配为基础的社会等级可能会阻碍群体的延续和发展, 因为支配者不一定具备任务所需的知识和技能, 但却拥有资源分配的优先权。群体通常会惩罚那些试图用暴力和攻击手段获得高地位的成员(Anderson & Kilduff, 2009b)。因此, 人类的社会地位主要通过能力路径获得(Anderson & Kilduff, 2009a; Chapais, 2015; Durkee et al., 2020)。

能力被定义为技能、专业知识、想法或信息, 它们对实现特定的任务目标具有明确的价值(Anderson & Kilduff, 2009a)。针对14个主要经济体国家(包括中国、美国、德国等)的跨文化研究表明, 拥有丰富的知识是个体提升社会地位的重要手段(Buss et al., 2020)。Garfield等人(2019)采用民族志研究方法, 从人际关系领域档案(the Human Relations Area Files, HRAF)所包含的60种随机抽取的文化样本中确定了1000多篇相关的档案记录, 证明了在现存的狩猎?采集社会中知识/技能对提升地位具有同样的作用。因此, 在人类群体中, 能力路径是广泛存在的。

3.1 能力路径的存在范围

关于非人动物是否存在能力等级系统, 研究结果并不一致。一些研究者认为, 在许多哺乳动物中, 群体领袖通常是年长者, 而年龄可以作为知识经验的外显指标, 这可以证明动物也存在能力等级(Lewis et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Tokuyama & Furuichi, 2017)。然而, 上述研究存在两个问题:①混淆了社会地位和领导力的概念。Smith和van Vugt (2020) 指出, 尽管领导力与地位高度相关, 但两者存在本质区别, 领导力是指个体在集体行动中对群体决策具有不成比例的影响, 而地位表征个体获取资源的优先级; 在动物中, 领导力与地位并不总是完全匹配。比如低地位的斑点鬣狗往往在狩猎中领导群体行动(Smith et al., 2008), 而年长的大象虽然拥有领导权, 却没有获得额外的食物或交配机会(Archie et al., 2006); ②年龄不一定是能力的可靠指标。年龄是一个综合指标, 包含了知识、技能和战斗能力等各种信息, 尽管个体的知识经验会随年龄增长得到提升, 但身体衰老可能导致战斗能力和技能水平下降, 因而实证研究并没有发现年龄与地位之间存在直接关系(Reyes-Garcia et al., 2008; Stibbard- Hawkes et al., 2018)。

另一些研究者主张用社会中心度(social centrality)测量非人灵长类的能力等级, 它由被其他个体接近的次数和获得理毛服务的频率构建。因为在能力等级中, 低地位者会主动与高地位者接触, 寻求接近并保持对他们的关注, 而在支配等级中, 低地位者会尽可能避免接触, 保持距离(Lee & Yamamoto, 2023; Reyes-Garcia et al., 2008)。例如, Kulahci等(2018)发现, 能够解决新的觅食问题的狐猴不仅更多被模仿, 且提高了社会中心度。然而, 社会中心度不仅受到亲缘关系、年龄、性别等多个因素影响(Beisner et al., 2020; Canteloup et al., 2021), 也能被支配等级正向预测, 因为个体可通过依附高支配者以换取争斗中的支持(Wooddell et al., 2020)。因此, 社会中心度并不能有效区分两种等级系统。

3.2 能力路径的演化成因与判断标准

由于在动物群体中寻找能力路径困难重重, Henrich和Gil-White (2001)认为, 这一路径为人类所独有, 因为它依赖于文化学习, 一种人类特有的社会学习形式。社会学习是个体通过观察其他动物或人, 或者与之互动而实现的学习; 它可以有效降低个体获取适应性信息的成本, 帮助生物体快速适应环境, 其基本形式在动物群体中广泛存在(Legare, 2017)。而文化学习是一种“高保真”社会学习形式, 使信息能够在群体内“无损”传递, 从而让群体成员有足够时间可以对知识和技能进行微小改进, 形成文化现象(Boyd et al., 2011)。这种高保真信息传递建立在真正的模仿基础上。所谓模仿(imitation)是指复制一个主体的行动, 包括完整的动作序列、行为意图和结果。而动物的学习更多是一种模拟(emulation), 即复制行为结果或目标, 比如黑猩猩在观察到人类榜样往瓶子里注水得到花生后, 会向容器里吐口水以使花生漂浮在伸手可及的范围内(Cacchione & Amici, 2020)。相比模仿, 模拟忽略了大量潜在的有用信息, 是一种效率低下的学习方式, 已获得的知识会在传播过程中反复丢失, 因而需要不断被重新学习。

Henrich和Gil-White (2001)提出“信息商品理论” (information goods theory)来解释能力路径的产生。由于觅食方式日益复杂化, 人类必须掌握更多生存技能。向有能力的群体成员学习是一种获得适应性知识的低成本方式。个体以尊重作为一种“货币”换取近距离接触模仿对象的机会, 从而更精确地掌握相关技能, 否则便会被淘汰。这种选择压力使个体必须学会依据能力对群体成员排序, 筛选出合适的模仿对象。因此, 能力強的个体就会获得高声望(prestige)。大量研究证实了声望在文化学习中的这种作用(Brand et al., 2020; Hewlett, 2021; Miu et al., 2020)。声望高的人比声望低的人受到更多关注(Cheng et al., 2013; Gerpott et al., 2018), 且被更多模仿(Brand et al., 2021; Burdett et al., 2016)。因此, 文化学习既是能力路径产生的原因, 也可作为其是否存在的一个判断指标。

然而, 实验表明, 黑猩猩也会像人类一样, 筛选出能力强的个体作为模仿对象(Kendal et al., 2015)。更进一步的研究发现, 非人灵长类不仅能复制行为结果, 也能复制行为本身。因此文化学习并非人类所独有。以长尾猴为被试的“人工水果”取食实验发现, 不同动作组的猴子倾向于模仿本组的动作来获得食物, 表明它们也能复制行为本身, 展现出真正的模仿(van de Waal et al., 2015; van de Waal & Whiten, 2012)。田野调查也发现, 在10个不同的野生黑猩猩群落中, 每个群体都发展出了取食白蚁的独特技术组合; 研究者认为, 生态因素不能解释不同群体觅食方式上的差异, 因为这些方法涉及特定的身体姿势, 存在高保真的动作模仿(Boesch et al., 2020)。脑成像研究表明, 这种动作模仿能力是建立在镜像神经元基础上, 因为它有助于识别动作而不是意图(Thompson et al., 2022)。而这种神经元在包括猕猴等非人灵长类身上皆有发现(Bonini et al., 2022)。因此, 神经层面和行为层面的研究都表明非人灵长类拥有真正的模仿能力。

3.3 人类与非人灵长类能力路径的比较

即便非人灵长类存在文化学习以及能力等级系统, 其广度与深度也无法与人类相提并论。例如, 黑猩猩的模仿能力局限在手段?目的之间的联系是透明可见的情况, 一旦这种因果关系是在黑箱中操作, 它们的模仿便具有选择性而无法复制全部动作。在这种情况下, 人类儿童依然能完整复制动作序列, 因为他们具有过度模仿(overimitation)倾向。过度模仿可以保证儿童在不理解因果关系的情况下依然能高保真地掌握复杂技能(Shipton & Nielsen, 2015)。此外, Vale等(2021)的实验研究表明, 在黑猩猩群体中, 当任务难度提升时, 复杂的问题解决方案就难以被其他成员掌握并得到传播。脑成像研究提供了一种可能的神经机制解释:存在一种动作加工回路的种间差异, 即从猕猴到黑猩猩到人类, 前额叶腹外侧皮层(ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, vlPFC)的背侧流逐步增强, 反映了物种演化中日益精细的动作技能和身体模仿能力(Stout & Hecht, 2017)。

教学被看作是另一种文化学习形式, 指导者在有初学者在场的情况下刻意改变自己的行为, 以促进他人的学习(Cacchione & Amici, 2020)。先前的研究者认为教学可能是人类独有的文化学习方式, 但最近的研究表明, 在动物界教学行为比预想的普遍。比如成年猫鼬(meerkats)会提前去除蝎子的毒刺, 让幼崽在安全条件下学习如何捕食蝎子, 从而提高它们的狩猎技能; 除了猫鼬, 还有另外27个物种(比如蚂蚁、蜜蜂等)也存在潜在的教学行为(Gurven et al., 2020)。但这些动物的教学互动往往发生在亲子之间, 信息是垂直传播(vertical transmission), 这种学习方式不存在对象选择问题; 并且垂直传播的范围极受限制, 难以在更广泛的群体中进行信息交流从而形成文化。而人类的教学活动更多是一种信息的斜向传播(oblique transmission), 个体会从非父母的年长者中选出拥有丰富知识和技能者作为模仿对象, 从而促进适应性信息在群体内快速传播(Hewlett, 2021)。因此, 只有人类的教学行为以能力路径为基础。

总之, 相比支配路径, 动物群体中能力路径的研究要困难得多。无论年龄还是社会中心度都不足以成为精确的衡量指标。文化学习当然不能等同于能力等级, 但可以作为能力等级的一个关键特征。模仿及其神经基础镜像神经元在多种非人灵长类身上都被观察到, 因此能力路径并非人类所独有。未来研究可以量化群体中不同个体工具使用的情况作为能力水平的衡量指标, 以资源分配的顺序和数量建立等级梯度, 同时将体型大小作为控制变量, 以排除支配等级的干扰, 进而研究动物的能力水平与社会等级之间的关系。在此基础上可以进一步考察存在能力等级的动物群体是否也都存在文化学习现象, 以确定文化学习在能力路径形成中的作用。

4 美德路径

尽管支配路径和能力路径可能是人类提升社会地位的主要手段, 但它们不足以解释人类获取地位的全部方式。比如, Kyl-Heku和Buss (1996)的研究指出, 在他们所调查的26种地位获取手段中, 有一半无法被归类为支配路径或者能力路径。因此, 一些研究者认为, 可能存在其他重要的路径。

4.1 美德路径的独立性

Bai (2017)提出存在第三种路径:美德路径。所谓美德(virtue), 是指一个人在道德上值得赞许的特征。美德与道德(morality)不同, 后者是对日常行为规范的遵从, 而前者包含了为他人利益而自愿做出的自我牺牲。拥有道德的人是“匹配者”, 遵从互惠利他的原则, 追求付出与回报的对等。而具有美德的人是“给予者”, 他们所给出的总是多于得到的。

Bai进一步指出, 美德路径是独立存在的, 而不像Henrich和Gil-White (2001)所认为的, 是能力路径的组成部分, 无法单独发挥作用。他认为, 美德路径的情感基础是钦佩(admiration), 而能力路径的情感基础是尊重(respect)。除此以外, 两种路径在前因变量、行为后果以及神经关联方面都存在差异。而在Henrich和Gil-White的理论中, 能力和美德被整合进了声望概念, 利他和慷慨等美德有利于能力者获得更多关注, 从而让个体的知识和技能被更多人模仿, 继而提升地位(Cheng, 2020; Henrich et al., 2015; Witkower et al., 2020)。但实证研究发现, 美德和能力交互作用不显著, 两者独立地对地位提升发挥作用(Bai, Ho, & Yan, 2020)。人类学和跨文化心理学研究也表明, 无论在现代工业社会中(Buss et al., 2020), 还是在狩猎?采集部落中(Hawkes & Bird, 2002; Lewis, 2022), 乐于分享资源对于男女在同伴群体中获取地位都至关重要。因此, 美德路径是独立的, 而非能力路径的一个组成部分或调节因素。

4.2 美德路径的存在范围

美德的标准多种多样, 但根据Bai (2017)的定义, 美德的本质特征乃是利他。动物尤其是非人灵长类是否存在美德路径首先也要解决它们是否具备利他属性这一问题。实际研究中, 这一问题通常导向对亲社会性的研究。非人灵长类亲社会实验最常使用食物分享范式。多数研究表明, 主动分享食物在它们身上极为罕见(Amici et al., 2014; Marshall-Pescini et al., 2016), 但一些研究者认为倭黑猩猩可能是个例外。它们比黑猩猩表现出更高的亲社会水平和社会容忍度, 且存在食物分享行为(Krupenye et al., 2018; Nolte & Call, 2021)。然而, 先前的实验可能存在练习效应、认知要求过高等问题, 新近研究采用多种范式来考察倭黑猩猩的亲社会性, 结果发现, 哪怕付出的代价很小它们也不会给其他群体成员提供食物奖励(Verspeek, van Leeuwen, Lameris, Staes, & Stevens, 2022; Verspeek, van Leeuwen, Lameris, & Stevens, 2022)。先前所观察到的食物分享事件中, 倭黑猩猩并没有主动提供食物, 只是容忍了其他个体拿走或者窃取自己的食物(Yamamoto, 2015)。因此, 倭黑猩猩可能具有被动亲社会行为, 但不具备主动亲社会行为。

再则, 根据Bai (2017)的理论, 只有亲社会的终极形式——利他主义, 才被看作是美德。所谓亲社会是任何有利于他人的积极社会行为——无论是无私的还是自私的, 代价高昂的还是零成本的(Amici et al., 2014; Krupenye et al., 2018)。而利他行为是指任何为他人带来益处而对行动者造成直接成本的行为, 它包括两种:生物利他主义(biological altruism)和心理利他主义(psychological altruism) (Vlerick, 2020)。生物利他主义关注行为, 是指通过降低自身的繁殖成功率来提高他人的繁殖成功率, 即動物所具有的亲缘利他(帮助携带部分自身基因的亲属)和互惠利他(当前的利他行为在未来获得回报), 最终来看它们都能提高自身基因的总体适应性, 因此是一种“高明的自利”。心理利他主义关注动机, 指造福他人的愿望。只有人类存在非亲缘性的、无预期回报的心理利他主义, 比如当灾难发生时给陌生人捐款, 这种行为在很多时候会降低自身基因的总体适应性, 因而是一种真正的利他。

4.3 美德路径的演化成因

4.3.1 高成本信号理论和集体行动问题

心理利他为何能帮助个体获得地位?高成本信号理论(costly signaling theory)认为, 利他是一种昂贵但有效的手段, 传递个体作为潜在合作伙伴或伴侣的特质, 从而获得较高的社会评价; 因其代价高昂, 因此难以伪装(E. A. Smith & Bird, 2000)。研究者使用多种实验方法来检验高成本信号理论。结果发现, 在美德推断中, 人们更看重行为背后的动机而非行为本身, 而行为的成本(必须达到一定程度)比收益更能反映个体的利他动机(Bai, Ho, & Yan, 2020)。因此, 即使某些利他行为的实际效用更大, 人们也会认为成本更高的行为更值得赞扬(Johnson & Park, 2021)。一旦人们怀疑利他行为包含利己的动机, 那么利他者就会因真实性受到怀疑而得不到相应的地位(Bai, Ho, & Liu, 2020; Flynn & Yu, 2021)。

此外, Willer (2009)进一步指出, 利他行为表明了个体将群体利益置于个人利益之上; 作为一种补偿, 群体成员赋予其高地位, 以鼓励利他者进一步为集体做出贡献, 从而有利于解决集体行动问题。Lang等人(2022)采用2 (高/低成本组) × 2 (公开/隐藏组)公共物品博弈实验来研究高成本利他信号如何促进集体行动。结果发现, 高成本公开组的被试更愿意在后续实验中投入更多资金, 也会在后续组队中吸引具有合作倾向的个体; 相反, 具有自私倾向的个体则会因投入过高而拒绝与之组队。这一结果表明, 高成本利他信号通过两个方面促进了集体行动:一方面, 有利于筛选出具有利他倾向的团队成员; 另一方面, 促使利他者在后续的集体行动中付出更多。

4.3.2 人类美德路径产生的独特条件

为何心理利他主义只在人类群体中存在?Richerson等人(2016)提出, 随着原始人类生产力提高, 人口规模迅速扩大, 这产生了新的压力:群体间竞争的加剧和群体内合作的强化。当群体间竞争激化时, 群体内合作水平高的群体可以形成更大的群体规模和更强的战斗力, 从而战胜其他群体。只有心理利他主义才能促进大规模群体内合作(生物利他主义只在小规模群体当中产生作用), 这种行为无法通过自然选择产生, 因为搭便车者会比利他者拥有更高的适应性, 更有可能把基因传递下去。群体必须通过文化选择来赋予利他行为以社会价值(高地位), 使这种行为在群体中得到传播和延续。这一过程被称作文化群体选择(cultural group selection)。研究发现, 群体间的竞争会促进对群体内合作行为的奖励以及对搭便车行为的惩罚, 从而提高群体的竞争力(Francois et al., 2018)。并且, 文化相似性能够正向预测群体合作的倾向, 表明不同群体内的合作规范是通过对文化变异的群体选择演化而来的(Handley & Mathew, 2020)。

除了群体规模, 认知能力的限制是其他动物无法产生美德路径的另一个原因。正如高成本信号理论所指出的, 动机比行为更能反映利他品质, 所以人们首先需要对行为背后的动机进行推断, 这意味着一种成熟的心理理论 (theory of mind) (Krupenye & Call, 2019)。包括黑猩猩在内的非人灵长类虽然具备心理理论基础功能, 但无法推断其他个体关于外部世界的信念, 且它们更擅长在竞争领域中使用心理理论, 因此可能无法理解同伴的善意或互惠合作的意图(殷融, 2022)。此外, 自我驯化假说(self domestication hypothesis)认为, 在演化过程中人类增强了自我控制能力且弱化了情绪反应, 这使得人类群体的社会容忍度大大提高, 为人类演化出心理利他主义提供了条件(Hare, 2017)。总之, 外部环境的选择压力(群体规模)和内部认知的限制(心理理论、自我控制以及情绪反应)决定了只有人类社会能够产生美德路径。

4.4 美德路径的独特性

等级存在的意义乃是建立一种资源分配的顺序, 个体追求高等级以获得更多资源, 从而提高生物适应性。但美德路径建立在心理利他主义基础上, 个体因自我牺牲而降低生物适应性, 两者之间存在本质矛盾。为处理这一矛盾, 有必要区分广义社会等级和狭义社会等级。所谓狭义社会等级即包括人在内的动物为了资源分配而建立起来的一种“啄序”, 它是生物演化的产物。而在广义社会等级中, 人类追求社会地位不纯粹是为了获取更多资源, 也是为了获得他人的高度评价, 满足自尊的心理需要(Mahadevan et al., 2023), 它是文化演化的产物。由于本研究聚焦于人类, 因此本文采用广义社会等级概念, 将美德路径涵盖在内, 从而能够更准确、更完整地描述人类等级系统的演化。

总之, 美德路径是独立存在的, 且仅存在于人类群体中。动物虽然具有生物利他, 但只有人类存在心理利他。高成本利他行为表明个体具有真正的利他动机, 是潜在的合作对象, 从而在群体中产生亲社会规范, 促进大规模合作问题的解决。这种利他动机的判断建立在复杂心理理论基础上, 非人灵长类并不具备推断其他群体成员善意的能力。然而目前并不清楚, 多大的群体规模会超越生物利他的效用范围, 从而产生心理利他主义和美德路径。

5 三种等级路径的差异性分析

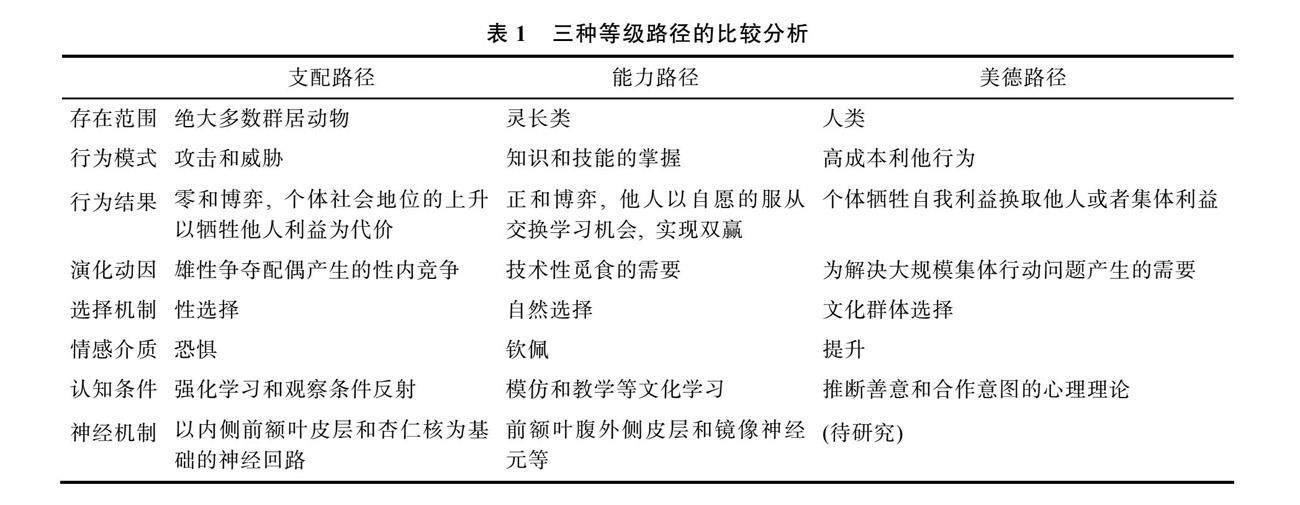

作为一种群体组织形式, 人类等级系统存在从简单到复杂, 从单维到多维的演化过程。无论支配路径、能力路径还是美德路径, 都是获得地位的有效手段。先前一些研究者(比如, Chapais, 2015; Cheng, 2020)并没有意识到人类等级的复杂性与多维性, 将不同路径混为一谈, 而从演化视角可以清晰地看到三种路径在多个方面都存在明显区别(详见表1)。

在诸多差异中, 行为模式和结果是三种路徑的本质区别:支配路径以攻击和威胁为手段, 等级竞争本质上是一场零和博弈, 个体社会地位的上升必然以牺牲他人利益为代价(Andrews-Fearon & Davidai, 2023); 能力路径更像是“自由贸易”, 知识和技能构成了社会传播中的“信息商品”, 群体成员以自愿的服从换取近距离学习的机会, 从

而实现双赢局面, 成员间的资源分配是正和博弈; 与前两种路径不同, 美德路径建立在心理利他主义基础上, 个体为了他人或群体利益而牺牲自身利益。

此外, 能力路径和美德路径在情感介质上的差异一直存在争议。Bai (2017)认为, 美德路径以钦佩为情感中介。但另一些研究者将钦佩视为在向上比较中感觉自身能力不如对方时所引发的积极情绪, 从而促进能力领域的社会学习(Algoe & Haidt, 2009; Onu, Kessler, & Smith, 2016)。根据这一理解, 钦佩是能力路径的情感中介。但在先前的理论中, 尊重才是能力路径的情感中介(Bai, 2017; Cheng et al., 2013; Henrich & Gil-White, 2001)。之所以产生这样的混淆是因为无论钦佩还是尊重都属于赞扬他人(other-praising)的情感族系(Algoe & Haidt, 2009)。事实上, 钦佩最开始同时指代对能力或道德领域卓越者的赞赏, 随着研究的深入催生了对两个领域概念分化的需求。

Algoe和Haidt (2009)首次提出将“钦佩”概念限定在能力领域, 用“提升” (elevation)指代由超越标准的美德所引发的情感, 它会使个体产生一种胸部“扩张”或打开的感觉, 感到温暖和愉悦, 伴有某种升华感, 从而产生模仿和践行美德行为的动机; 相反, 对卓越能力的钦佩则会激发个体自我完善的动机。这一分类方式被多数研究者认可与采纳(Kondoh & Okanoya, 2022; Nakatani et al., 2019; Onu, Kessler, & Smith, 2016; 黄玺 等, 2018), 也得到了一些实证研究的佐证。Onu, Kessler, Andonovska-Trajkovska等人(2016)的研究表明对外群体的能力评价能显著预测钦佩感, 而美德评

价对钦佩感的预测只是边缘显著。Pizarro等人(2021)发现, 提升感能够促进个人的集体认同, 增强助人意愿。Nakatani等人(2019)认为钦佩的客体是卓越行为, 而尊重关注的是作为整体的人。他们使用脑成像技术来探究两者的神经基础差异, 发现尽管钦佩和尊重所激活的脑区大量重叠, 但左前颞叶(anterior temporal lobe, ATL)的一部分更强烈地受到尊重的影响。这一区域与语义信息加工有关, 而尊重不仅要加工行为本身, 还需要整合当前和过往的信息来对整体的人做出评价。基于这一信息量的差异, 他们推测, 钦佩可能是尊重的一个子集。因此, 本研究主张采用Algoe和Haidt (2009)的观点, 即钦佩是能力路径的情感中介, 提升是美德路径的情感中介, 而尊重可能是对社会地位综合判断的情感反映。

6 总结和展望

社会等级是群居生活的产物。它可以有效减少群体内冲突, 节省群体成员的时间和精力, 降低受伤风险(Buss et al., 2020; Tibbetts et al., 2022), 也会对个体的身心健康及寿命产生重要影响(Anderson et al., 2022; Fournier, 2020)。自“啄序”发现至今, 社会等级的多维性和复杂性被逐步揭示出来, 从支配路径到能力路径再到美德路径, 等级系统的演化推动了人类社会朝着更加文明的方向发展。大量研究者的关注使这一领域积累了丰硕的成果, 然而我们与获得完整的演化图景仍有距离, 现有的结论还存在一些矛盾和不足之处。未来的研究可从以下几个方面展开:

6.1 不同动物群体性选择模式与支配等级的关系

尽管有多方面的证据表明同性竞争可能是支配路径产生的主要演化动因, 但仍然不能排除自然选择可能在其中的作用。理论上, 各种资源都可能引发群体内竞争, 并促成支配等级的形成。但现有研究表明, 支配等级主要存在于雄性群体中, 雄性比雌性更高大强壮且更有攻击性, 繁殖变异度更大。性别二态特征通常是性选择的结果, 不过也有研究表明, 自然选择时常在雄性和雌性中建立不同的表型, 比如女性为了生育需要而增加身体脂肪(Lassek & Gaulin, 2022)。

为了进一步证实同性竞争在支配等级形成中的作用, 今后研究可以比较不同择偶系统中支配等级的差异。多偶制群居动物相比单偶制群居动物在支配等级上可能更加陡峭。即使是多偶制动物, 其群体内的择偶竞争强度也是不同的, 这通常用生殖倾斜度(reproductive skew, 即存活后代数量的差异度)来表示(Leimar & Bshary, 2022)。生殖倾斜度越高, 意味着择偶竞争越激烈, 支配等级可能越陡峭。此外, 动物的择偶方式不是一成不变的。以人为例:随着更新世到来, 人类形成了低支配的小规模平等主义狩猎?采集社会, 并演化出从事相对一夫一妻制伴侣关系的动机, 雄性择偶竞争强度下降, 伴随这一变化的是人类体型性别二态性的缩小(Schacht & Kramer, 2019; Solomon & Ophir, 2020)。也就是说, 这一过程中性择强度的减弱和支配等级梯度变得缓和是同时发生的。但人类仅是一例, 未來研究可以从纵向角度系统考查不同动物, 尤其是灵长类的雄性择偶竞争强度与支配等级梯度随时间发生的变化, 从而更好地探究潜在的因果机制。

6.2 人类能力路径演化的特殊环境

特定路径的形成往往需要考虑到人类祖先环境中重复出现的选择压力。van Boekholt等人(2021)发现在所有灵长类物种中, 只有人类社会结构表现出促进社会学习的各种有利特征。此外, 在340万年前左右, 人类的饮食结构发生巨大变化, 从零散的植物资源向营养密集的、可预测的动物资源转变。制作片状石器、屠宰大型动物和扩大头颅容量等重要演化事件相继出现。这一转变使得人类比其他灵长类发展出了更多复杂技术(Marean, 2016)。再者, 更新世古人类以合作狩猎大型动物为主, 因此, 协调群体活动的能力对于人类祖先就显得尤为重要(Smith et al., 2012)。

总之, 技术性觅食、合作狩猎以及社会结构的独特性一起, 可能造成了人类社会异于其他动物社群的压力, 促成了支配等级系统向能力等级系统的转化。这种转变不是一蹴而就的, 极有可能是在非常漫长的时间里完成的。这些环境因素又是如何与文化学习产生作用, 目前也未可知。未来需要对更多不同群居动物的社会形态、文化学习以及能力等级的差异进行比较研究, 从而确定不同环境因素在造成等级形态差异方面的重要性。这可能需要考古学、人类学以及灵长类学等多学科协同研究, 尤其是对已灭绝人类祖先的社会形态探究, 将为更好地理解能力等级的演化提供关键信息。

6.3 美德路径演化的生物性基础探索

文化群体选择从远因机制(ultimate mechanism)视角解释了美德路径的产生, 但这一路径产生的生物性基础, 即近因机制(proximate mechanism)尚未得到充分探究。神经影像学研究发现, 利他行为激活了与共情以及奖励处理相关的脑区, 刺激大脑分泌荷尔蒙如多巴胺、催产素和血清素(Vlerick, 2020)。也就是说, 利他能够通过自我强化使个体获得心理满足。这可能是建立在人脑所具有的神经可塑性和多巴胺能奖励系统基础上, 它们在形成和改造神经回路方面发挥着重要作用(Sonne & Gash, 2018)。那么, 人类超越生物演化的范畴, 使追求地位本身成为一种目的, 而不是获取资源的手段, 是否也是建立在类似的神经机制基础上?这种等级心理的“自目的性”是只存在于美德路径中, 还是适用于所有路径?在支配路径中动物的大脑也表现出类似的奖赏机制, 为何动物没有产生超越生存和繁衍的动机?今后应通过实证研究方式, 结合神经、认知以及行为层面的跨物种比较, 进一步探索相关神经机制及其存在的普遍性。

此外, 基因层面的研究发现, 有972个基因解释了包括亲社会性在内的人类现代性特征的可遗传变异, 其中有267个基因在黑猩猩或尼安德特人(Neanderthals)身上是缺失的(Zwir et al., 2021)。这种基因型(genotype)上的差异可能决定了三个物种在亲社会上存在表型(phenotype)差异。因此, 黑猩猩很难在熟悉的社会伙伴关系之外进行合作, 因为在合作任务中, 黑猩猩表现出强烈的自利倾向(Laland & Seed, 2021)。而人类近亲尼安德特人虽然拥有强大的视觉空间能力和工具制造能力, 但与人类相比, 更不擅长社交和群体合作, 最终在4万年前走向灭绝(Gregory et al., 2021; Vaesen et al., 2021)。可能正是亲社会水平的差异, 导致黑猩猩和尼安德特人无法像人类一样产生美德路径, 从而解决大规模集体行动问题。今后研究应关注这一可能性, 通过考古学、神经科学以及遗传学的跨学科合作寻找确切的证据以揭示潜在的遗传机制。

参考文献

黄玺, 梁宏宇, 李放, 陈世民, 王巍欣, 林妙莲, 郑雪. (2018). 道德提升感:一种提升道德情操的积极道德情绪. 心理科学进展, 26(7), 1253?1263.

殷融. (2022). 读心的比较研究:非人灵长类与人类在心理理论上的异同点及其解释. 心理科学进展, 30(11), 2540? 2557.

Algoe, S. B., & Haidt, J. (2009). Witnessing excellence in action: The 'other-praising' emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(2), 105?127.

Amici, F., Visalberghi, E., & Call, J. (2014). Lack of prosociality in great apes, capuchin monkeys and spider monkeys: Convergent evidence from two different food distribution tasks. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 281(1793), 20141699.

Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009a). The pursuit of status in social groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 295?298.

Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009b). Why do dominant personalities attain influence in face-to-face groups? The competence-signaling effects of trait dominance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(2), 491?503.

Anderson, J. A., Lea, A. J., Voyles, T. N., Akinyi, M. Y., Nyakundi, R., Ochola, L., ... Tung, J. (2022). Distinct gene regulatory signatures of dominance rank and social bond strength in wild baboons. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 377(1845), 20200441.

Andrews-Fearon, P., & Davidai, S. (2023). Is status a zero- sum game? Zero-sum beliefs increase people's preference for dominance but not prestige. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 152(2), 389?409.

Archie, E. A., Morrison, T. A., Foley, C. A. H., Moss, C. J., & Alberts, S. C. (2006). Dominance rank relationships among wild female African elephants, Loxodonta africana. Animal Behaviour, 71(1), 117?127.

Bai, F. (2017). Beyond dominance and competence: A moral virtue theory of status attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(3), 203?227.

Bai, F., Ho, G. C. C., & Liu, W. (2020). Do status incentives undermine morality-based status attainment? Investigating the mediating role of perceived authenticity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 158, 126?138.

Bai, F., Ho, G. C. C., & Yan, J. (2020). Does virtue lead to status? Testing the moral virtue theory of status attainment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 501?531.

Beisner, B., Braun, N., Pósfai, M., Vandeleest, J., D'Souza, R., & McCowan, B. (2020). A multiplex centrality metric for complex social networks: Sex, social status, and family structure predict multiplex centrality in rhesus macaques. PeerJ, 8, e8712.

Boesch, C., Kalan, A. K., Mundry, R., Arandjelovic, M., Pika, S., Dieguez, P., ... Kühl, H. S. (2020). Chimpanzee ethnography reveals unexpected cultural diversity. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(9), 910?916.

Bonini, L., Rotunno, C., Arcuri, E., & Gallese, V. (2022). Mirror neurons 30 years later: Implications and applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(9), 767?781.

Boucherie, P. H., Gallego-Abenza, M., Massen, J. J. M., & Bugnyar, T. (2022). Dominance in a socially dynamic setting: Hierarchical structure and conflict dynamics in ravens' foraging groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 377(1845), 20200446.

Boyd, R., Richerson, P. J., & Henrich, J. (2011). The cultural niche: Why social learning is essential for human adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(suppl. 2), 10918?10925.

Brand, C. O., Heap, S., Morgan, T. J. H., & Mesoudi, A. (2020). The emergence and adaptive use of prestige in an online social learning task. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 12095.

Brand, C. O., Mesoudi, A., & Morgan, T. J. H. (2021). Trusting the experts: The domain-specificity of prestige- biased social learning. PLoS One, 16(8), e0255346.

Breuer, T., Robbins, A. M., Boesch, C., & Robbins, M. M. (2012). Phenotypic correlates of male reproductive success in western gorillas. Journal of Human Evolution, 62(4), 466?472.

Burdett, E. R., Lucas, A. J., Buchsbaum, D., McGuigan, N., Wood, L. A., & Whiten, A. (2016). Do children copy an expert or a majority? Examining selective learning in instrumental and normative contexts. PLoS One, 11(10), e0164698.

Buss, D. M., Durkee, P. K., Shackelford, T. K., Bowdle, B. F., Schmitt, D. P., Brase, G. L., ... Trofimova, I. (2020). Human status criteria: Sex differences and similarities across 14 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 979?998.

Cacchione, T., & Amici, F. (2020). Insights from comparative research on social and cultural learning. In S. Hunnius & M. Meyer (Eds.), New Perspectives on Early Social- Cognitive Development (Vol. 254, pp. 247?270). Elsevier Academic Press.

Canteloup, C., Puga-Gonzalez, I., Sueur, C., & van de Waal, E. (2021). The consistency of individual centrality across time and networks in wild vervet monkeys. American Journal of Primatology, 83(2), e23232.

Carre, J. M., & Archer, J. (2018). Testosterone and human behavior: The role of individual and contextual variables. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 149?153.

Cassini, M. H. (2019). A mixed model of the evolution of polygyny and sexual size dimorphism in mammals. Mammal Review, 50(1), 112?120.

Chapais, B. (2015). Competence and the evolutionary origins of status and power in humans. Human Nature, 26(2), 161?183.

Chen, Y. R., Peterson, R. S., Phillips, D. J., Podolny, J. M., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2012). Introduction to the special issue: Bringing status to the table-attaining, maintaining, and experiencing status in organizations and markets. Organization Science, 23(2), 299?307.

Cheng, J. T. (2020). Dominance, prestige, and the role of leveling in human social hierarchy and equality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 238?244.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103?125.

Couchoux, C., Garant, D., Aubert, M., Clermont, J., & Réale, D. (2021). Behavioral variation in natural contests: Integrating plasticity and personality. Behavioral Ecology, 32(2), 277?285.

Durkee, P. K., Lukaszewski, A. W., & Buss, D. M. (2020). Psychological foundations of human status allocation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(35), 21235?21241.

Fan, Z., Zhu, H., Zhou, T., Wang, S., Wu, Y., & Hu, H. (2019). Using the tube test to measure social hierarchy in mice. Nature Protocols, 14(3), 819?831.

Federspiel, I. G., Boeckle, M., von Bayern, A. M. P., & Emery, N. J. (2019). Exploring individual and social learning in jackdaws (Corvus monedula). Learning & Behavior, 47(3), 258?270.

Flynn, F. J., & Yu, A. (2021). Better to give than reciprocate? Status and reciprocity in prosocial exchange. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(1), 115?136.

Fournier, M. A. (2020). Dimensions of human hierarchy as determinants of health and happiness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 110?114.

Francois, P., Fujiwara, T., & van Ypersele, T. (2018). The origins of human prosociality: Cultural group selection in the workplace and the laboratory. Science Advances, 4(9), eaat2201.

Garfield, Z. H., Hubbard, R. L., & Hagen, E. H. (2019). Evolutionary models of leadership: Tests and synthesis. Human Nature, 30(1), 23?58.

Gerpott, F. H., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., Silvis, J. D., & Van Vugt, M. (2018). In the eye of the beholder? An eye-tracking experiment on emergent leadership in team interactions. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(4), 523?532.

Gregory, M. D., Kippenhan, J. S., Kohn, P., Eisenberg, D. P., Callicott, J. H., Kolachana, B., & Berman, K. F. (2021). Neanderthal-derived genetic variation is associated with functional connectivity in the brains of living humans. Brain Connectivity, 11(1), 38?44.

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., Gangestad, S. W., Perea, E. F., Shapiro, J. R., & Kenrick, D. T. (2009). Aggress to impress: Hostility as an evolved context-dependent strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 980? 994.

Grosenick, L., Clement, T. S., & Fernald, R. D. (2007). Fish can infer social rank by observation alone. Nature, 445(7126), 429?432.

Gurven, M. D., Davison, R. J., & Kraft, T. S. (2020). The optimal timing of teaching and learning across the life course. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1803), 20190500.

Handley, C., & Mathew, S. (2020). Human large-scale cooperation as a product of competition between cultural groups. Nature Communications, 11(1), 702.

Hare, B. (2017). Survival of the Friendliest: Homo sapiens evolved via selection for prosociality. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(1), 155?186.

Hawkes, K., & Bird, R. B. (2002). Showing off, handicap signaling, and the evolution of men's work. Evolutionary Anthropology, 11(2), 58?67.

Henrich, J., Chudek, M., & Boyd, R. (2015). The Big Man Mechanism: How prestige fosters cooperation and creates prosocial leaders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 370(1683), 20150013.

Henrich, J., & Gil-White, F. J. (2001). The evolution of prestige - Freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22(3), 165?196.

Hewlett, B. (2021). Social learning and innovation in adolescence : A comparative study of Aka and Chabu hunter-gatherers of central and eastern Africa. Human Nature, 32(1), 239?278.

Jiang, Y., Zhou, J., Song, B.-L., Wang, Y., Zhang, D.-L., Zhang, Z.-T., ... Liu, Y.-J. (2023). 5-HT1A receptor in the central amygdala and 5-HT2A receptor in the basolateral amygdala are involved in social hierarchy in male mice. European Journal of Pharmacology, 957, 176027.

Johnson, S. G. B., & Park, S. Y. (2021). Moral signaling through donations of money and time. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 165, 183?196.

Kendal, R., Hopper, L. M., Whiten, A., Brosnan, S. F., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J., & Hoppitt, W. (2015). Chimpanzees copy dominant and knowledgeable individuals: Implications for cultural diversity. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(1), 65?72.

King, G. (2022). Baboon perspectives on the ecology and behavior of early human ancestors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(45), e2116182119.

Kondoh, S., & Okanoya, K. (2022). Performance in a task improves when subjects experience respect, rather than admiration, for those teaching them. Discover Psychology, 2(1), 38.

Krupenye, C., & Call, J. (2019). Theory of mind in animals: Current and future directions. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Cognitive Science, 10(6), e1503.

Krupenye, C., & Hare, B. (2018). Bonobos prefer individuals that hinder others over those that help. Current Biology, 28(2), 280?286.e5

Krupenye, C., Tan, J., & Hare, B. (2018). Bonobos voluntarily hand food to others but not toys or tools. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 285(1886), 20181536.

Kulahci, I. G., Ghazanfar, A. A., & Rubenstein, D. I. (2018). Knowledgeable lemurs become more central in social networks. Current Biology, 28(8), 1306?1310.e2

Kyl-Heku, L. M., & Buss, D. M. (1996). Tactics as units of analysis in personality psychology: An illustration using tactics of hierarchy negotiation. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(4), 497?517.

Laland, K., & Seed, A. (2021). Understanding human cognitive uniqueness. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 689?716.

Lang, M., Chvaja, R., Grant Purzycki, B., Václavík, D., & Staněk, R. (2022). Advertising cooperative phenotype through costly signals facilitates collective action. Royal Society Open Science, 9(5), 202202.

Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2022). Substantial but misunderstood human sexual dimorphism results mainly from sexual selection on males and natural selection on females. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 859931.

Lee, S. H., & Yamamoto, S. (2023). The evolution of prestige: Perspectives and hypotheses from comparative studies. New Ideas in Psychology, 68, 100987.

Legare, C. H. (2017). Cumulative cultural learning: Development and diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(30), 7877?7883.

Leimar, O., & Bshary, R. (2022). Reproductive skew, fighting costs and winner-loser effects in social dominance evolution. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 91(5), 1036?1046.

Levy, E. J., Zipple, M. N., McLean, E., Campos, F. A., Dasari, M., Fogel, A. S., ... Archie, E. A. (2020). A comparison of dominance rank metrics reveals multiple competitive landscapes in an animal society. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 287(1934), 20201013.

Lewis, J. S., Wartzok, D., & Heithaus, M. R. (2013). Individuals as information sources: Could followers benefit from leaders knowledge? Behaviour, 150(6), 635?657.

Lewis, R. J. (2022). Aggression, rank and power: Why hens (and other animals) do not always peck according to their strength. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 377(1845), 20200434.

Ligneul, R., Obeso, I., Ruff, C. C., & Dreher, J. C. (2016). Dynamical representation of dominance relationships in the human rostromedial prefrontal cortex. Current Biology, 26(23), 3107?3115.

Lukaszewski, A. W., Simmons, Z. L., Anderson, C., & Roney, J. R. (2016). The role of physical formidability in human social status allocation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(3), 385?406.

Mahadevan, N., Gregg, A. P., & Sedikides, C. (2023). Daily fluctuations in social status, self-esteem, and clinically relevant emotions: Testing hierometer theory and social rank theory at a within-person level. Journal of Personality, 91(2), 519?536.

Marean, C. W. (2016). The transition to foraging for dense and predictable resources and its impact on the evolution of modern humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150239.

Marshall-Pescini, S., Dale, R., Quervel-Chaumette, M., & Range, F. (2016). Critical issues in experimental studies of prosociality in non-human species. Animal Cognition, 19(4), 679?705.

Miu, E., Gulley, N., Laland, K. N., & Rendell, L. (2020). Flexible learning, rather than inveterate innovation or copying, drives cumulative knowledge gain. Science Advances, 6(23), eaaz0286.

Montana, L., King, W. J., Coulson, G., Garant, D., & Festa- Bianchet, M. (2022). Large eastern grey kangaroo males are dominant but do not monopolize matings. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 76(6), 78.

Muniz, L., Perry, S., Manson, J. H., Gilkenson, H., Gros- Louis, J., & Vigilant, L. (2010). Male dominance and reproductive success in wild white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus) at Lomas Barbudal, Costa Rica. American Journal of Primatology, 72(12), 1118?1130.

Munuera, J., Rigotti, M., & Salzman, C. D. (2018). Shared neural coding for social hierarchy and reward value in primate amygdala. Nature Neuroscience, 21(3), 415?423.

Murlanova, K., Kirby, M., Libergod, L., Pletnikov, M., & Pinhasov, A. (2022). Multidimensional nature of dominant behavior: Insights from behavioral neuroscience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 132, 603?620.

Nakatani, H., Muto, S., Nonaka, Y., Nakai, T., Fujimura, T., & Okanoya, K. (2019). Respect and admiration differentially activate the anterior temporal lobe. Neuroscience Research, 144, 40?47.

Nolte, S., & Call, J. (2021). Targeted helping and cooperation in zoo-living chimpanzees and bonobos. Royal Society Open Science, 8(3), 201688.

Onu, D., Kessler, T., Andonovska-Trajkovska, D., Fritsche, I., Midson, G. R., & Smith, J. R. (2016). Inspired by the outgroup: A social identity analysis of intergroup admiration. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(6), 713?731.

Onu, D., Kessler, T., & Smith, J. R. (2016). Admiration: A conceptual review. Emotion Review, 8(3), 218?230.

Padilla-Coreano, N., Batra, K., Patarino, M., Chen, Z., Rock, R. R., Zhang, R., ... Tye, K. M. (2022). Cortical ensembles orchestrate social competition through hypothalamic outputs. Nature, 603(7902), 667?671.

Pizarro, J. J., Basabe, N., Fernandez, I., Carrera, P., Apodaca, P., Man Ging, C. I., ... Páez, D. (2021). Self-transcendent emotions and their social effects: Awe, Elevation and Kama Muta promote a human identification and motivations to help others. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 709859.

Plavcan, J. M. (2012). Sexual size dimorphism, canine dimorphism, and male-male competition in primates: Where do humans fit in? Human Nature, 23(1), 45?67.

Puts, D. A. (2010). Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(3), 157?175.

Reddon, A. R., Voisin, M. R., Menon, N., Marsh-Rollo, S. E., Wong, M. Y. L., & Balshine, S. (2011). Rules of engagement for resource contests in a social fish. Animal Behaviour, 82(1), 93?99.

Redhead, D., & Power, E. A. (2022). Social hierarchies and social networks in humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 377(1845), 20200440.

Reyes-Garcia, V., Molina, J. L., Broesch, J., Calvet, L., Huanca, T., Saus, J., ... McDade, T. W. (2008). Do the aged and knowledgeable men enjoy more prestige? A test of predictions from the prestige-bias model of cultural transmission. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(4), 275? 281.

Richerson, P., Baldini, R., Bell, A. V., Demps, K., Frost, K., Hillis, V., ... Zefferman, M. (2016). Cultural group selection plays an essential role in explaining human cooperation: A sketch of the evidence. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 39, e30.

Schacht, R., & Kramer, K. L. (2019). Are we monogamous? A review of the evolution of pair-bonding in humans and its contemporary variation cross-culturally. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 230.

Schjelderup-Ebbe, T. (1922). Beitr?ge zur sozialpsychologie des haushuhns [Observation on the social psychology of domestic fowls]. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 88, 225?252.

Shipton, C., & Nielsen, M. (2015). Before cumulative culture: The evolutionary origins of overimitation and shared intentionality. Human Nature, 26(3), 331?345.

Shizuka, D., & McDonald, D. B. (2015). The network motif architecture of dominance hierarchies. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 12(105), 20150080.

Smith, E. A., & Bird, R. L. B. (2000). Turtle hunting and tombstone opening: Public generosity as costly signaling. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(4), 245?261.

Smith, J. E., Estrada, J. R., Richards, H. R., Dawes, S. E., Mitsos, K., & Holekamp, K. E. (2015). Collective movements, leadership and consensus costs at reunions in spotted hyaenas. Animal Behaviour, 105, 187?200.

Smith, J. E., Kolowski, J. M., Graham, K. E., Dawes, S. E., & Holekamp, K. E. (2008). Social and ecological determinants of fission?fusion dynamics in the spotted hyaena. Animal Behaviour, 76(3), 619?636.

Smith, J. E., Swanson, E. M., Reed, D., & Holekamp, K. E. (2012). Evolution of cooperation among mammalian carnivores and its relevance to hominin evolution. Current Anthropology, 53(S6), S436?S452.

Smith, J. E., & van Vugt, M. (2020). Leadership and status in mammalian societies: Context matters. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(4), 263?264.

Solomon, N. G., & Ophir, A. G. (2020). Editorial: What's love got to do with it: The evolution of monogamy. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8, 110.

Sonne, J. W. H., & Gash, D. M. (2018). Psychopathy to altruism: Neurobiology of the selfish?selfless spectrum. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 575.

Stibbard-Hawkes, D. N. E., Attenborough, R. D., & Marlowe, F. W. (2018). A noisy signal: To what extent are Hadza hunting reputations predictive of actual hunting skills? Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(6), 639?651.

Stout, D., & Hecht, E. E. (2017). Evolutionary neuroscience of cumulative culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(30), 7861?7868.

Terrizzi, B. F., Woodward, A. M., & Beier, J. S. (2020). Young children and adults associate social power with indifference to others' needs. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104867.

Thomas, H. J., Connor, J. P., & Scott, J. G. (2018). Why do children and adolescents bully their peers? A critical review of key theoretical frameworks. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(5), 437?451.

Thompson, E. L., Bird, G., & Catmur, C. (2022). Mirror neuron brain regions contribute to identifying actions, but not intentions. Human Brain Mapping, 43(16), 4901?4913.

Tibbetts, E. A., Pardo-Sanchez, J., & Weise, C. (2022). The establishment and maintenance of dominance hierarchies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 377(1845), 20200450.

Tokuyama, N., & Furuichi, T. (2017). Leadership of old females in collective departures in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus) at Wamba. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 71(3), 55.

Tracy, J. L., Mercadante, E., Witkower, Z., & Cheng, J. T. (2020). The evolution of pride and social hierarchy. In B. Gawronski (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 62, pp. 51?114). Elsevier Academic Press.

Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man (pp. 136?179). Aldine-Atherton.

Vaesen, K., Dusseldorp, G. L., & Brandt, M. J. (2021). An emerging consensus in palaeoanthropology: Demography was the main factor responsible for the disappearance of Neanderthals. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 4925.

Vale, G. L., McGuigan, N., Burdett, E., Lambeth, S. P., Lucas, A., Rawlings, B., ... Whiten, A. (2021). Why do chimpanzees have diverse behavioral repertoires yet lack more complex cultures? Invention and social information use in a cumulative task. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(3), 247?258.

van Boekholt, B., van de Waal, E., & Sterck, E. H. M. (2021). Organized to learn: The influence of social structure on social learning opportunities in a group. iScience, 24(2), 102117.

van de Waal, E., Claidière, N., & Whiten, A. (2015). Wild vervet monkeys copy alternative methods for opening an artificial fruit. Animal Cognition, 18(3), 617?627.

van de Waal, E., & Whiten, A. (2012). Spontaneous emergence, imitation and spread of alternative foraging techniques among groups of vervet monkeys. PLoS One, 7(10), e47008.

van der Ploeg, R., Steglich, C., & Veenstra, R. (2020). The way bullying works: How new ties facilitate the mutual reinforcement of status and bullying in elementary schools. Social Networks, 60, 71?82.

Verspeek, J., van Leeuwen, E. J. C., Lameris, D. W., Staes, N., & Stevens, J. M. G. (2022). Adult bonobos show no prosociality in both prosocial choice task and group service paradigm. PeerJ, 10, e12849.

Verspeek, J., van Leeuwen, E. J. C., Lameris, D. W., & Stevens, J. M. G. (2022). Self-interest precludes prosocial juice provisioning in a free choice group experiment in bonobos. Primates, 63(6), 603?610.

Vlerick, M. (2020). Explaining human altruism. Synthese, 199(1?2), 2395?2413.

Wang, F., Zhu, J., Zhu, H., Zhang, Q., Lin, Z., & Hu, H. (2011). Bidirectional control of social hierarchy by synaptic efficacy in medial prefrontal cortex. Science, 334(6056), 693?697.

Willer, R. (2009). Groups reward individual sacrifice: The status solution to the collective action problem. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 23?43.

Winegard, B. M., Winegard, B., & Geary, D. C. (2014). Eastwood's brawn and Einstein's brain: An evolutionary account of dominance, prestige, and precarious manhood. Review of General Psychology, 18(1), 34?48.

Witkower, Z., Tracy, J. L., Cheng, J. T., & Henrich, J. (2020). Two signals of social rank: Prestige and dominance are associated with distinct nonverbal displays. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(1), 89?120.

Wong, M., & Balshine, S. (2011). The evolution of cooperative breeding in the African cichlid fish, Neolamprologus pulcher. Biological Reviews, 86(2), 511?530.

Wooddell, L. J., Kaburu, S. S. K., & Dettmer, A. M. (2020). Dominance rank predicts social network position across developmental stages in rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology, 82(11), e23024.

Wright, E., Galbany, J., McFarlin, S. C., Ndayishimiye, E., Stoinski, T. S., & Robbins, M. M. (2019). Male body size, dominance rank and strategic use of aggression in a group-living mammal. Animal Behaviour, 151, 87?102.

Yamamoto, S. (2015). Non-reciprocal but peaceful fruit sharing in wild bonobos in Wamba. Behaviour, 152(3?4), 335?357.

Zhou, T. T., Zhu, H., Fan, Z. X., Wang, F., Chen, Y., Liang, H. X., ... Hu, H. L. (2017). History of winning remodels thalamo-PFC circuit to reinforce social dominance. Science, 357(6347), 162?168.

Zink, C. F., Tong, Y. X., Chen, Q., Bassett, D. S., Stein, J. L., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2008). Know your place: Neural processing of social hierarchy in humans. Neuron, 58(2), 273?283.

Zwir, I., Del-Val, C., Hintsanen, M., Cloninger, K. M., Romero-Zaliz, R., Mesa, A., ... Cloninger, C. R. (2021). Evolution of genetic networks for human creativity. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 354?376.

Routes to ascend the social hierarchy and related evolutions:

Implications from comparative studies

ZHENG Minglu1, LIU Linshu2, YE Haosheng2

(1 Department of Psychology, Shanxi Normal University, Taiyuan 030031, China)

(2 Center for Mind and Brain Science, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China)

Abstract: Social hierarchies are dynamic multidimensional systems. The dominance route via aggression and threat to acquire resources has evolved under intense sexual selection pressure. By contrast, the competence route, which emphasizes the role of knowledge/skill in gaining status, is a consequence of the evolution of cultural learning driven by the increasing sophistication of foraging techniques. However, the virtue route characterized by psychological altruism is thought to be unique to human-being, and is the result of cultural evolution favoring large-scale collective actions. The three routes are different in the scope of existence, behavioral pattern and outcome, evolutionary cause and emotional medium. Future research could further clarify the relationship between sexual selection patterns and dominance levels in different species. Multi-discipline studies may also be adopted to explore the human environment in which the competence route has evolved, as well as the biological basis of the virtue route.

Keywords: social hierarchies, dominance, competence, virtue, evolutionary cause