The Silk Road and East-West Cultural Exchange

This book is a collection of the authors research on the Silk Road. The book explores the direction of the Han and Tang Silk Roads, the relationship between the Silk Roads and certain regions or towns, and the cultural exchange between the East and the West through the Silk Roads.

The Silk Road and East-West Cultural Exchange

Rong Xinjiang

Peking University Press

March 2022

99.00 (CNY)

Rong Xinjiang

Rong Xinjiang is a Boya Chair Professor of the Department of History and the Center for Ancient Chinese History at Peking University, a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, a member of the Discipline Evaluation Group of the 7th-8th Academic Degrees Committee of the State Council, and president of the Dunhuang and Turpan Society of China.

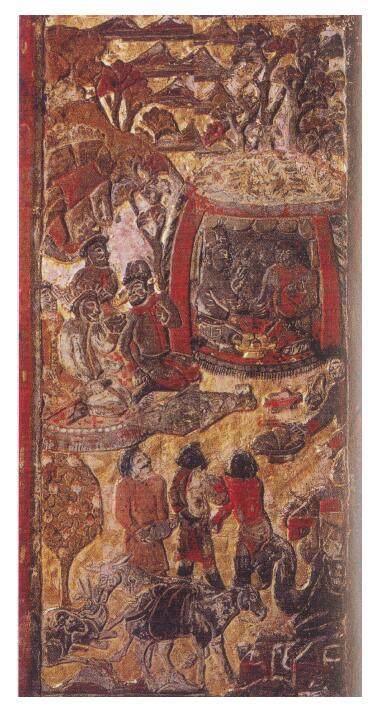

To the east and south of China lies the ocean, to the west are deserts and mountains, and to the north are the Gobi Desert and forests, placing it in a relatively enclosed geographical environment, which is not conducive to communication with the outside world. However, China has never been self-isolated; through both the terrestrial and maritime Silk Road, it has maintained extensive contact with the external world, both contributing to and absorbing it. In the historical process of East-West cultural exchange, the Silk Road played an extremely important role.

The Silk Road Is a “Living” Route

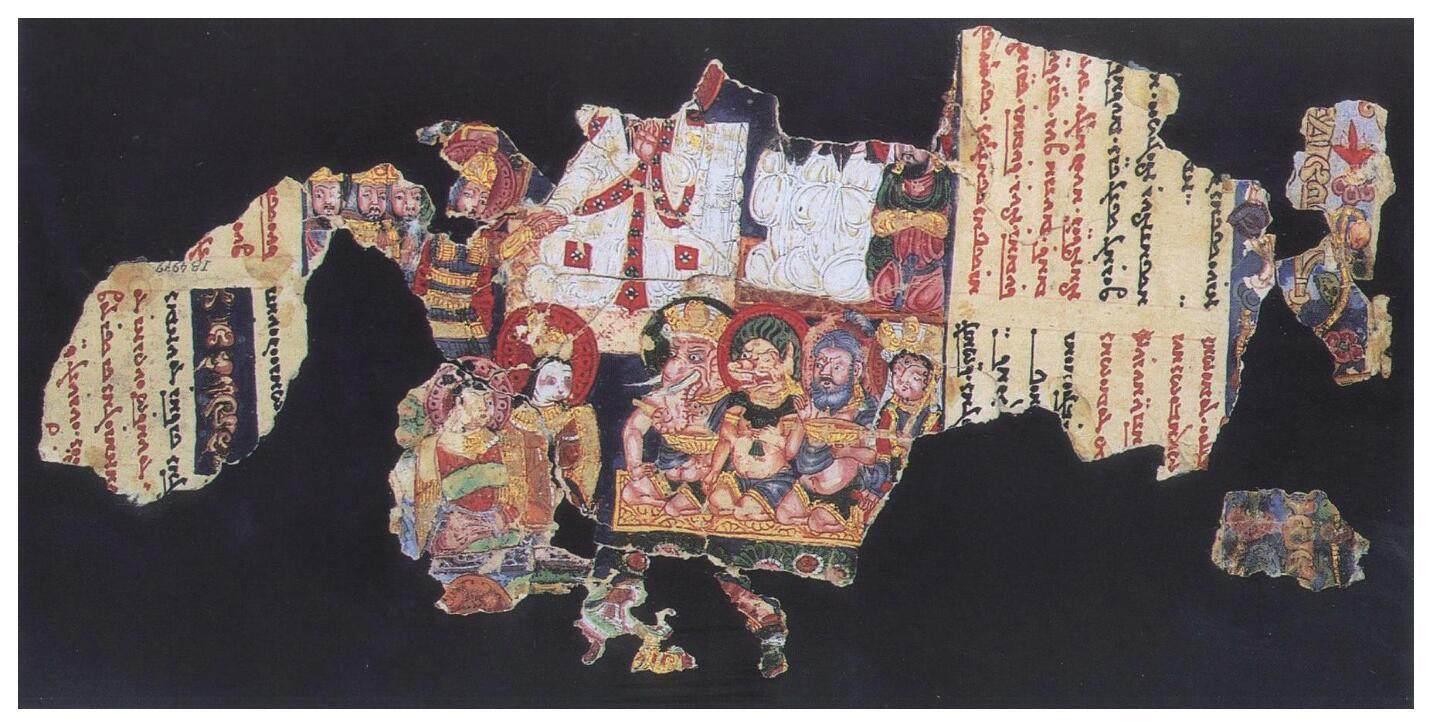

The term “Silk Road” was coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen to denote the trading routes that were primarily used for silk trade between Han Dynasty China, the southern and western regions of Central Asia, and India. However, with the deepening of academic research and advancements in archaeology in modern times, the meaning of the Silk Road has broadened, extending its scope significantly. Indeed, the Silk Road existed between the East and West long before the Han Dynasty, and it was not limited to exchanges between China and Central and South Asia but also included West Asia, the Mediterranean world, and regions connected by the maritime Silk Road such as the Korean Peninsula, Japan, and Southeast Asia. The traded goods were not limited to silk but included various handicrafts, plants, animals, and artworks. Because silk, which was abundantly produced in China, has long held a very important position in the history of the Silk Road, the term “Silk Road” signifies the ancient routes of East-West exchange that were fundamentally centered around China. Just like silk, the Silk Road sometimes appears as strands extending out, some routes clear and others intermittent. At other times, its like a vast net, encompassing a broad area, occasionally producing splendid brocades. Therefore, we should not rigidly view the Silk Road. There are different Silk Roads for different eras.

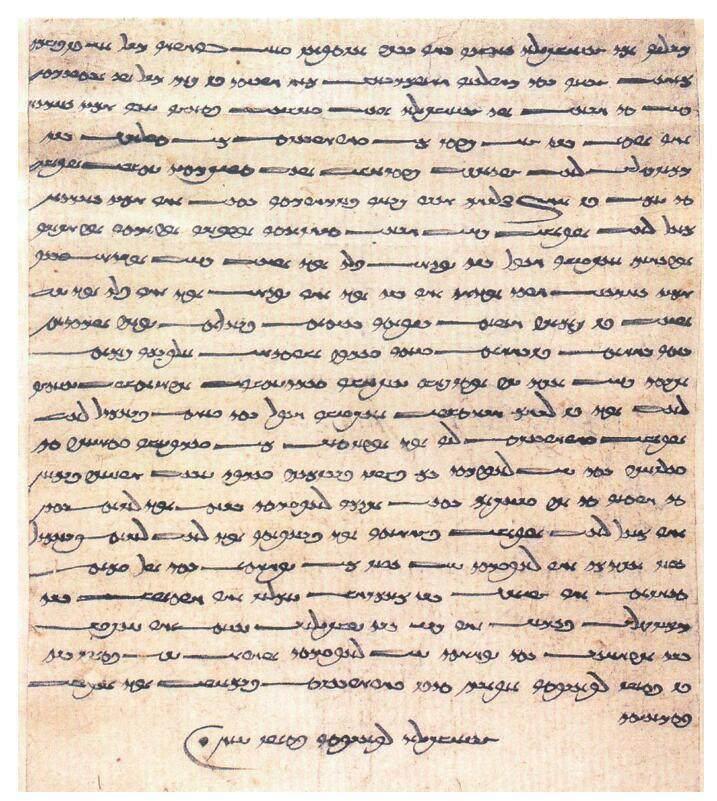

The basic routes of the Silk Road during the Han and Tang dynasties started from Changan or Luoyang, through the Hexi Corridor, the Tarim Basin, over the Pamir Plateau, into Central Asia, Iran, Arabia, and the Mediterranean world. By sea, it started from the southeastern coast, through the South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, to the east and west coasts of India, then to the Persian Gulf, Arabian Peninsula, Red Sea, and the Mediterranean, and even to the eastern coast of North Africa. The Silk Road is a “living” route, as its direction has shifted in different historical periods due to factors such as politics, religion, and nature. For instance, during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the Xianbei rulers in the north not only were at enmity with the Southern Dynasties but also frequently clashed with the Rouran Khanate to their north. We have found records in Turfan documenting that between 474 CE and 475 CE, Kanishkas Khotan Kingdom escorted envoys from various countries out of its territory. These few lines of text tell us that envoys from the Southern Dynasty Liu Song, the Tarim Basins Karasahr and Kucha, Northwestern Indias Udyana, and Central Indias Brahmin Kingdoms all had to pass through Khotan (Turfan) on their way to the Mongolian Plateaus Rouran Khanate. This document sketches out the routes of South-North and East-West exchange in the latter half of the 5th century, indicating that despite the turmoil of war, the Silk Road connecting East Asia, North Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia remained unobstructed (Refer to: Rong Xinjiangs Kanishkas Khotan Kingdom and Its Relations with the Rouran, Western Regions in Historical Research, 2007, Issue 2).

The fate of certain regions along the main route of the Silk Road, such as the narrow definition of the Western Regions, specifically the Tarim Basin and Turfan Basin in Xinjiang, especially some oasis kingdoms of the Western Regions, was closely linked to whether the Silk Road was open. Because transit trade on the Silk Road was a major source of income for these oasis kingdoms, and cultural prosperity also depended on the flow and penetration of Eastern and Western civilizations, these oasis kingdoms made great efforts to keep the Silk Road open, facilitating commercial trade and cultural exchange on the Silk Road, aiming to firmly control the Silk Road in their own hands (Refer to: Rong Xinjiangs The Silk Road and Ancient Xinjiang in The Silk Road and Ancient Culture of Xinjiang, edited by Qi Xiaoshan and Wang Bo, Xinjiang Peoples Publishing House, 2008, pages 298--303).

Historically, powerful forces around the Silk Road have also hoped to control this route, which holds both economic and military value, such as the Xiongnu, Han, Rouran, Hephthalites, Türks, Tang, and Uighurs, among others. After stabilizing the Central Plains, the Tang Dynasty began its campaign against Gaochang in 640 CE and conquered the Western Turkic Khanate by 658 CE, transferring the suzerainty of Central Asia and the Western Regions to the Tang Dynasty. The Tang Dynasty established the Anxi and Beiting Protectorates to control the north and south of the Tianshan Mountains in the Western Regions and implemented a system of post stations and beacon towers according to the Central Plains system to ensure the smooth flow of the Silk Road (Refer to: Rong Xinjiangs The Anxi Protectorate and the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty -- Focused on the Documents Unearthed in Turfan, compiled by the Xinjiang Kucha Society, Kucha Studies Research, Issue 5, Xinjiang University Press, 2012, pages 154--166; and The Beiting on the Silk Road from the 7th to the 10th Century, edited by Chen Chunsheng, Maritime and Land Routes and World Civilization, Commercial Press, 2013, pages 64--73). Some documents unearthed in Turfan provide numerous records of merchants traveling on the Silk Road, as well as the strenuous efforts made by powerful state systems to maintain the routes (Refer to: Cheng Xilins Research on Tang Dynasty Passes, Zhonghua Book Company, 2000).

Many towns along the Silk Road have contributed to the maintenance of the Silk Road and East-West cultural exchange at different historical periods. We can list a series of names, such as the Southern Route of the Silk Road in the Western Regions Khotan and Loulan, the Northern Routes Kucha, Karasahr, and Khoco, Hexis Dunhuang and Wuwei, as well as the Central Plains regions of Guyuan, Changan, and Luoyang, even some towns that seem remote today played a very important role in the history of East-West traffic during certain historical periods. For example, Tongwan City, located at the northernmost tip of Shaanxi in Jingbian County, became a key node on the route of interaction between the Western world and the Northern Wei capital, Pingcheng, after the Northern Wei Dynasty eliminated the Northern Liang regime in Hexi in 439 CE and opened a shortcut from Hexi through Bole (Lingzhou), Xiazhou (Tongwan City), along the southern edge of the Ordos Desert to Pingcheng (Refer to Maeda Masaos Historical Geography of Pingcheng, translated by Li Ping, Bibliographic Literature Publishing House, 1994, pages 134--161; Rong Xinjiangs Tongwan City in the Medieval East-West Traffic History, compiled by the Northwest Environmental Development Center of Shaanxi Normal University, Comprehensive Study on the Tongwan City Site, Sanqin Publishing House, 2004, pages 29--33).

The Silk Road is a “living” route; as long as it is active, the nations and towns along it also thrive. Simultaneously, the Silk Road has evolved with changes in politics, religion, and other factors over different eras, with various towns playing specific historical roles in their respective times.

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Dujiangyan

- Traditional Chinese Crafts in the Context of Silk Road Civilization -- Interview with Master Li Maodi, a Master of Zhuoni Tao Inkstone Making in Gansu’s Zhuoni

- Encounters and Cultural Boundaries Between East and West: Cultural Transmission Under the Belt and Road Initiative

- The Splendor of the Maritime Silk Road: A Major Theme of Globalization Leading to the Americas

- Revelations from the Civilizations of the Silk Road

- The Historical Context of the Silk Road