Dysmetabolic comorbidities and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a stairway to metabolic dysfunctionassociated steatotic liver disease

Carmen Colaci, Maria Luisa Gambardella, Giuseppe Guido Maria Scarlata, Luigi Boccuto, Carmela Colica, Francesco Luzza, Emidio Scarpellini, Nahum Mendez-Sanchez, Ludovico Abenavoli

1Department of Health Sciences, University “Magna Graecia” of Catanzaro, Viale Europa, Catanzaro 88100, Italy.

2Healthcare Genetics and Genomics, School of Nursing, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29631, USA.

3CNR, IBFM, Second Department, Via Tommaso Campanella, Catanzaro 88100, Italy.

4Translational Research in Gastrointestinal Disorders (T.A.R.G.I.D.), Gasthuisberg University Hospital, KULeuven, Leuven 3000,Belgium.

5Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City 04510, Mexico.

Abstract Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease.This term does not describe the pathogenetic mechanisms and complications associated with NAFLD.The new definition, Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver disease (MASLD), emphasizes the relationship between NAFLD and cardiometabolic comorbidities.Cardiovascular disease features, such as arterial hypertension and atherosclerosis,are frequently associated with patients with MASLD.Furthermore, these patients have a high risk of developing neoplastic diseases, primarily hepatocellular carcinoma, but also extrahepatic tumors, such as esophageal, gastric,and pancreatic cancers.Moreover, several studies showed the correlation between MASLD and endocrine disease.The imbalance of the gut microbiota, systemic inflammation, obesity, and insulin resistance play a key role in the development of these complications.This narrative review aims to clarify the evolution from NAFLD to the new nomenclature MASLD and evaluate its complications.

Keywords: Hepatic steatosis, inflammation, cardiometabolic comorbidities, gut microbiota, obesity, carcinogenesis,liver damage

INTRODUCTION

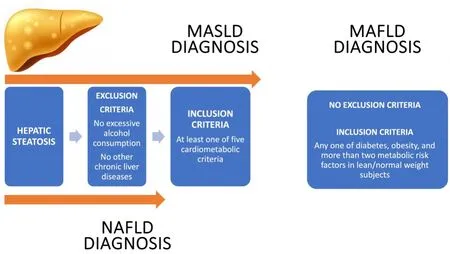

The most common cause of chronic liver disease (CLD) in the world is Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease(NAFLD), especially in Western countries.NAFLD was defined by the presence of Steatotic Liver Disease(SLD) without significant alcohol consumption or other chronic liver diseases[1].Significant alcohol consumption is defined as an intake of > 21 drinks and > 14 drinks per week in two years in men and women, respectively[2].However, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a risk factor of health status for every alcohol level[3].Indeed, low alcohol consumption could induce the progression from liver steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and fibrosis.For example, in a rat model, the combination of sweeteners, such as fructose and alcohol, is responsible for changes in the liver and in the serum characterizing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[4].Usually, NAFLD includes a broad spectrum of liver damage, possibly due to hepatocytic damage, inflammatory processes, and fibrosis[5].The worldwide prevalence of NAFLD is around 25%-30% in the adult population.The highest prevalence rates have been reported in Latin America, the Middle East, and North Africa.The NAFLD diffusion is a consequence of the worldwide overweight “pandemic”.Indeed, WHO estimated that obesity affects more than 2 billion people worldwide[6].The cause of this development is an unhealthy lifestyle.Western diet, overconsumption of alcohol, sedentary lifestyle, and smoking are the main risk factors of overweight[7].These factors are strongly influenced by socio-demographic factors (such as gender, age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status)[8].The highest prevalence of obesity is observed in countries across America and Europe[9].However, the prevalence has increased in developing countries in the last years, from 8% in 1980 to 13% in 2013, respectively[10].The NAFLD mortality rate is 12.60 per 1,000 patients/year.The leading cause of death in patients with NAFLD is represented by cardiovascular events triggered by overweight/obesity,and by hepatic complications only when inflammation (NASH) and fibrosis develop[11].Subsequently, the definition of NAFLD was considered inaccurate to reflect its pathogenesis.Moreover, it did not allow the correct stratification of patients for management when alcohol consumption is associated with increased caloric intake[4].In 2020, the new nomenclature of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease(MAFLD) was proposed[12,13].MAFLD was defined by the presence of SLD associated with inclusion criteria:T2DM, overweight/obesity (body mass index, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), or the presence of metabolic dysregulation[1].Additionally, MAFLD co-exists with other chronic liver diseases and is independent of alcoholic intake[12].The disease progression is faster in MAFLD than in NAFLD due to dysmetabolic comorbidities.Indeed, recent evidence underlined that MAFLD was related to a higher rate of fibrosis and NASH[13].Therefore, there are several limitations in the MAFLD term: the different etiologies and the inappropriate use of the term “fatty”.After four rounds of the Delphi survey, the definition of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver disease (MASLD) was chosen to replace NAFLD.MASLD was defined as SLD with at least one of five cardiometabolic risk factors without excessive alcohol intake (less than 140-30 g/week and 210-420 g/week for females and males, respectively)[14].The diagnostic criteria of NAFLD and MASLD are summarized in Figure 1.

Aim

This recent change in nomenclature has created serious questions about its use.This narrative review aims to clarify the evolution from NAFLD to the new nomenclature MASLD and evaluate its complications.

THE CHANGE IN NOMENCLATURE

Figure 1.Diagnostic criteria of NAFLD, MAFLD and MASLD.MASLD: Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver disease;NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; MAFLD: Metabolic Dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.

The main limitation of the term NAFLD is the difficulty of emphasizing the role of metabolic dysfunction in the pathogenesis of the disease.For this reason, a new term, MAFLD, has been proposed, which takes into account the metabolic and hepatic comorbidities associated with liver steatosis.In this way, it better captures both the hepatic and extrahepatic aspects of the patient compared to NAFLD[15].Several studies have shown that patients with MAFLD have a worse hepatic profile compared to patients with NAFLD,which seems to be correlated not only with the presence of metabolic comorbidities but also hepatic[15-18].Therefore, excluding patients with other hepatic etiologies in NAFLD would result in a failure to manage metabolic features in subjects who instead require multi-specialty approaches.A retrospective study analyzed the general characteristics of 175 patients with hepatic steatosis diagnosed by liver biopsy.Among these, 43.8% met only the criteria for MAFLD and 4.9% only those for NAFLD.Patients with only MAFLD had a higher BMI compared to those with NAFLD, and hepatic and metabolic comorbidities were not present in patients with NAFLD alone.Histologically, 48.1% of patients with MAFLD showed advancedstage fibrosis[16].These results were confirmed by another study conducted on 765 patients with hepatic steatosis.The percentage of patients with significant fibrosis was 93.9% in patients with MAFLD and 73% in patients with NAFLD[17].Furthermore, another study observed not only an increase in fibrosis but also in biochemical indices of liver damage in patients with MAFLD alone compared to patients with NAFLD alone[18].MAFLD, compared to NAFLD, is associated with both an increased severity of hepatic conditions and an increased risk of extrahepatic manifestations associated with metabolic comorbidities.In this regard,Huanget al.observed an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with MAFLD alone compared to patients with NAFLD alone[18].The increased risk of CVD in MAFLD was confirmed by a study performed on 8,962,813 patients without previous CVD with a follow-up of ten years, which demonstrated the presence of 182,423 new cardiovascular events in MAFLD patients[19].In addition,MAFLD is associated with an increased prevalence of renal comorbidities compared to NAFLD.In a study performed on 12,571 individuals, of whom 30.2% had MAFLD and 36.2% had NAFLD, patients with MAFLD had a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease(CKD) compared to patients with NAFLD[20].Finally, MAFLD, in addition to increasing the risk of hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations, is associated with increased mortality compared to NAFLD.In fact, a study conducted on 7,761 patients showed an increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in MAFLD patients compared to subjects with NAFLD[21].Although MAFLD offers a better clinical framework for patients, the term “fatty” is considered stigmatizing.For this reason, the replacement of the term fatty with “steatotic” has been proposed, thus introducing the term MASLD.However, MASLD determines a semantic improvement, but it has different diagnostic criteria compared to MAFLD.In fact, the MASLD definition includes patients with a lower metabolic risk and excludes patients with other chronic liver diseases.However, this approach could be limiting in a real-life context[22].In this regard, a recent study has highlighted how MASLD has a higher capture of lean patients compared to MAFLD[23].Probably due to these differences, MASLD tends to fairly reproduce the NAFLD scenario, while MAFLD probably captures hepatic and extrahepatic outcomes more accurately.A recent study compared the clinical characteristics of patients with NAFLD, MAFLD, and MASLD.It was observed that in terms of hepatic, renal damage, and metabolic comorbidities, MAFLD was associated with worse outcomes than NAFLD, while MASLD presented clinical features overlapping with NAFLD[24].Additionally, MAFLD is associated with higher cardiovascular, T2DM, and cancer-related mortality than MASLD[25].These results may be related to MASLD involving a larger number of patients with a healthier metabolic profile compared to MAFLD and the exclusion of patients with hepatic comorbidities.In this context, Wanget al.have proposed to divide the MASLD patients into pure MASLD, MetALD (MASLD associated with increased alcohol consumption),and combinatorial MASLD (with other hepatic comorbidities) to avoid excluding patients with coexistent liver pathologies and facilitate their clinical management[26].Overall, these nomenclatures are applicable to various types of patients in clinical practice.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MASLD

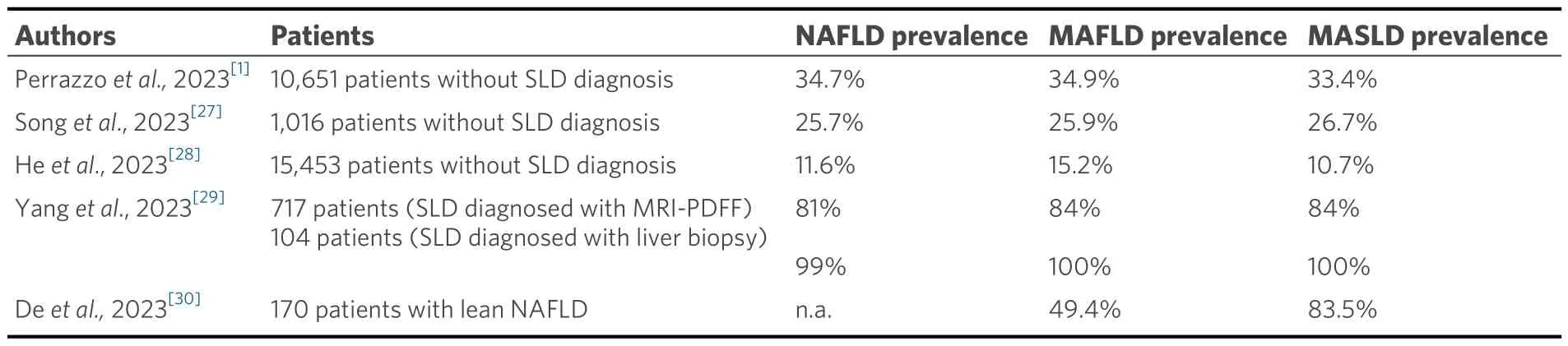

To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the epidemiology of MASLD in the general population,but only in individuals with risk factors.According to Perazzoet al., epidemiological data from NAFLD and MAFLD in the general population can apply to the MASLD definition.In a cohort of 10,651 individuals without SLD diagnosis, the prevalence of NAFLD, MAFLD, and MASLD was 34.7%, 34.9%, and 33.4%,respectively[1].Subsequently, Songet al.assessed the prevalence of specific SLD subtypes among 1,016 randomly selected individuals with SLD diagnosed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy.NAFLD,MAFLD, and MASLD prevalence were 25.7%, 25.9%, and 26.7%, respectively[27].In another study, among 15,453 subjects, the prevalence of NAFLD, MAFLD, and MASLD was 11.6%, 15.2%, and 10.7%,respectively[28].In a single-center cohort study of 745 patients, with SLD diagnosis based on magnetic resonance imaging derived proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), the prevalence of NAFLD, MAFLD,and MASLD was 81%, 84%, and 84%, respectively.However, among 104 patients with SLD diagnosed with liver biopsy, the prevalence changes (99% NAFLD, 100% both MAFLD and MASLD)[17].These studies showed no significant difference in prevalence between MASLD, NAFLD and MAFLD in the general population[1,27-29].However, these results in a target population might change.For example, the prevalence of MASLD and MAFLD in lean patients is different.Among 170 patients with lean NAFLD, 142 (83.5%)satisfied the MASLD criteria, while only 84 (49.4%) had MAFLD.Despite this, it should be considered that lean NAFLD is a relatively rare case compared to the overwhelming majority of obese patients[30].Therefore,more clinical trials on the target population are needed.Table 1 summarizes the epidemiological studies regarding NAFLD, MAFLD, and MASLD.

RISK FACTORS OF MASLD

Age, gender, tobacco, ethnicity, and genetic factors

Various risk factors, such as older age, male gender, tobacco, ethnicity, and genetic factors, are involved in the development of MASLD[1,31,32].The prevalence of MASLD in males is higher than in females(26%vs.13%)[11].Indeed, sex hormones have an important role in the metabolism of macronutrients.Specifically, estrogen promotes lipid metabolism by increasing the expression of lipoprotein lipase, an enzyme involved in triglyceride hydrolysis, and inhibiting lipolysis, which converts triglycerides into fatty acids.At the same time, progesterone may increase metabolic rate and energy expenditure, contributing to changes in appetite and weight regulation, while testosterone affects lipid metabolism by enhancing lipolysis, the degradation of stored fat, and reducing adipocyte proliferation and differentiation.Furthermore, this latter influences glucose metabolism by enhancing insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle[33].Estrogen has been shown to have protective effects on the liver, including reducing hepatic fat accumulation and inflammation (NASH)[34-37].As a result, premenopausal women usually have a lower risk of fatty liver disease compared to age-matched men.However, after menopause, when estrogen levels decline, women may become more susceptible to the disease development[38].Furthermore,differences in body fat distribution between males and females may also influence the development of liver steatosis: men tend to accumulate fat in the abdominal region (android obesity), which is associated with a higher risk of metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance, while women typically store fat in the hips and thighs (gynoid obesity), which may confer protection from the disease development[39].In addition, tobacco and alcohol use promotes the development of liver steatosis[40].In this regard, men consume more alcohol and tobacco than women.For this reason, the male gender and an unhealthy lifestyle are risk factors linked to MASLD development[41].Furthermore, a recent study showed that the number of alcoholic liver disease and MASLD-related deaths was higher in the white American population compared to the African American population during the 1999-2020 period[32].Finally, genetics play a key role in the development of fatty liver disease.Recent studies have identified various genetic factors that contribute to an individual's susceptibility to MASLD and its progression.One such factor is thepatatin-like phospholipase domaincontaining 3(PNPLA3) gene, which has been strongly associated with MASLD risk.PNPLA3 p.I148M variant has been found to increase the accumulation of fat in the liver and elevate the risk of developing the disease and its more severe forms[42].In this regard, recent investigations indicated that the prevalence of the PNPLA3 p.I148M variant was found to be highest among Hispanics (49%), followed by European-Americans (23%) and African-Americans (17%)[43,44].At the same time, variations in thetransmembrane 6 superfamily member 2(TM6SF2) gene have also been implicated in fatty liver disease.Some TM6SF2 variants are associated with increased liver fat content and higher risks of MASLD and its complications,including liver fibrosis and cirrhosis[45].In this regard, a recent study revealed that Caucasian individuals who were homozygous for the variant exhibited notably increased levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase in comparison to heterozygous carriers.Additionally, Caucasian populations demonstrated significantly higher liver fat content, unlike Hispanics, when comparing homozygous and heterozygous carriers[46].

Table 1.Epidemiological studies about NAFLD, MAFLD and MASLD

Cardiovascular and metabolic features

Low levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and an increase in glucose levels, homeostatic model assessment, triglycerides and BMI are positively correlated with hepatic steatosis, fibrosis progression, and the outcome of patients, including mortality.In this regard, it is necessary to assess the medical records and the historical data (especially the daily alcohol intake) of patients and then the clinical-laboratory parameters already mentioned[1,47-49].The predominant cardiovascular risk factor of MASLD is BMI >23 kg/m2[17].T2DM is an independent predictor of MASLD and its complications, especially if associated with tobacco consumption[50,51].In this context, several classes of antidiabetic drugs have favorable effects on liver function[52].The lifestyle plays an important role in the MASLD pathogenesis.Indeed, poor sleep quality and an unhealthy diet, such as a Western diet (characterized by high salt content and highly processed foods), are risk factors for MASLD development[53-55].On the other hand, the use of the Mediterranean diet in MASLD patients improves disease outcomes[56,57].The protective effect of plant-based food is also related to linalool.Linalool attenuates oxidative stress, inhibits lipogenesis, and promotes fatty acid oxidation, thereby reducing the accumulation of fats in the liver[58].Neighborhood-level social determinants of health are an important factor for MASLD outcomes.Indeed, “affluence” compared to“disadvantage” was associated with lower mortality risk, incident CVD, and incident liver-related events[59].An unhealthy lifestyle affects sleep quality, which in turn is a risk factor for MASLD development[60].Increased levels of bile acids (BA) are related to a higher prevalence of MASLD[53,61].

Inflammatory bowel diseases

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) determine a chronic and systemic inflammation state.This condition is an independent risk factor for MASLD in lean patients[62,63].

GUT MICROBIOTA IN MASLD

Gut microbiota in health and disease

Gut microbiota is a complex ecosystem comprising approximately 1014bacteria, withFirmicutesandBacteroidetesas predominant phyla.Its eubiosis maintains the health status[64].However, its imbalance(dysbiosis) has been linked to the development of T2DM, IBD, CKD, and liver diseases[65].The microbiota's role in metabolizing choline, phosphatidylcholine, and carnitine leads to trimethylamine-N-oxide, which is associated with atherosclerosis and increased mortality in CVD and CKD[66].Gut dysbiosis is correlated with the development of colorectal cancer (CRC)[67].Indeed, CRC patients have a higher abundance ofBacteroidetesbut a lower abundance ofFirmicutesphyla[68].IBDs are linked toProteobacteria/Firmicutesimbalance[69,70].

Gut microbiota in MASLD pathogenesis

Recent research focuses on the role of gut dysbiosis in CLD, including MASLD[71,72].Pre-clinical studies indicate thatBacteroidetesare linked to MASLD development, and targeted interventions can mitigate disease progression[73].Qiaoet al.evaluate how the higher abundance ofBacteroides xylanisolvensin the intestinal tract of attenuated mice reduced MASLD progression[74,75].A recent study showed how a high-fat diet (HFD) induced MASLD, alteringFirmicutes/Bacteroidetesratio.Additionally, treatment with a butyrate-producing bacterium,Kineothrix alysoides, mitigated liver fat accumulation by restoring gut eubiosis[76].Further investigations explored the association between gut microbiota and MASLD complications, revealing specific bacterial strains' potential therapeutic effects:Bacteroides vulgatusreduced atherosclerotic lesion formation, whileBacteroides uniformisreduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels,alleviating hepatic steatosis severity[77,78].Dysbiosis promotes the fermentation of complex carbohydrates,leading to SCFAs production[79-81].Furthermore, lactate produced byLactobacillusandBifidobacteriumgenera prolongs post-meal satiety by providing a substrate for neuronal cells[82,83].Gut imbalance and altered BA homeostasis may contribute to metabolic dysregulation in T2DM and obesity[84-85].Additionally, oxygenfree radicals modulated by the bacterial microflora could overcome antioxidant barriers that cause cellular damage, inflammation, and even apoptosis.Excessive generation of oxygen free radicals caused by gut dysbiosis and translocation of bacterial endotoxin to the liver is closely related to the pathogenesis of NAFLD and dysmetabolic comorbidities that promote the progression into MASLD[86].Liver damage is linked to an altered intestinal epithelial barrier.In a pre-clinical study, an HFD-induced gut dysbiosis with intestinal vascular barrier damage led to bacterial translocation into the portal circulation.Genetic manipulation of the β-catenin pathway and obeticholic acid treatment prevented barrier disruption[87].In another study, mice with liver cirrhosis exhibited increased gut permeability, bacterial translocation, and FXR receptor modulation.Treatment with FXR agonists improved the epithelial barrier, reducing bacterial translocation and liver damage[88].Figure 2 summarizes the pathway that involves the gut microbiota in MASLD pathogenesis.

Figure 2.Gut microbiota and MASLD pathogenesis.MASLD: Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease; BAs: Bile Acids;BMI: Body Mass Index; FFA: Free Fatty Acids; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoproteins Cholesterol.

MASLD COMPLICATIONS

Relationship between liver steatosis and metabolic comorbidities

The new nomenclature MASLD emphasizes the relationship between NAFLD and metabolic comorbidities.Recent studies reveal a 46.7% prevalence of MASLD in T2DM patients, while the cardiovascular event rate was 2.03 per 100 person-years in MASLD individuals[89,90].In MASLD, intrahepatic toxic lipid accumulation induces endothelial dysfunction and atherogenic dyslipidemia, marked by reduced HDL and elevated lowdensity lipoproteins and triglycerides levels[91].The liver produces inflammatory biomarkers that usually increase in MASLD patients[92].Visceral adiposity in MASLD alters hormone metabolism, adipokine production, and insulin-related factors, fostering systemic inflammation and insulin resistance.Elevated insulin-like growth factor 1 levels correlate with CRC risk.Adiponectin and leptin, reduced in obese MASLD patients, influence CRC progression[93-95].Gut dysbiosis could also mediate MASLD-associated carcinogenesis, probably through increased intestinal permeability in both the small and large intestine,leading to bacterial translocation, systemic inflammation, and tumorigenesis, as shown in CRC[96].Increased permeability of the small intestine is known in patients with CLD.In a recent study, small intestinal permeability was assessed by a double sugar (lactulose:rhamnose) assay in patients with CLD and in healthy controls.Small intestinal permeability was significantly higher in the CLD group than in healthy controls[97].Furthermore, in a recent study, the bacterial composition in the small intestine was evaluated through biopsies during double-balloon enteroscopy.As reported by the Authors,ProteobacteriaandFirmicutesphyla were abundant in the jejunum and proximal ileum, whileFirmicutesandBacteroidetesphyla were abundant in the distal ileum[98].

MASLD and non-dysmetabolic diseases

MASLD is linked to non-dysmetabolic diseases, including CKD, IBD, endocrinopathies, and lung diseases.MASLD patients exhibit a higher prevalence of CKD, potentially associated with hyperuricemia or T2DM[99].Studies indicate a correlation between hypothyroidism severity and MASLD, while limited evidence is available on hyperthyroidism.Low prolactin levels are associated with MASLD in women[100].NAFLD is related to decreased adult lung function and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome development[101],while data on MASLD are lacking.MASLD patients have a higher risk of developing sarcopenia due to nutritional disorders, gut dysbiosis, and insulin resistance[102,103].A mutual relationship between sarcopenia and insulin resistance exists due to mammalian target complex 1 rapamycin (mTORC1) action in skeletal muscle.Hyperinsulinemia activates mTORC1, but prolonged activation causes a negative feedback signal,leading to mTORC1 inhibition, autophagy, and increased protein degradation[104].

Hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks among the most prevalent solid tumors globally and stands as the third leading cause of mortality worldwide.Major culprits for HCC include hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, alcohol abuse, exposure to aflatoxin, and schistosomiasis[105].Notably,NAFLD has emerged as a significant contributor to HCC development in recent years[106].Particularly in the United States, NAFLD has become the fastest-growing cause of HCC among liver transplant recipients and candidates.A similar trend was observed in Europe, South Korea, and Southeast Asia, where NAFLDrelated HCC cases have risen over the last two decades[107].Notably, HCC associated with NAFLD tends to occur at an older age compared to viral-induced cases, often diagnosed at later stages, leading to poorer survival rates compared to those linked to viral or alcoholic hepatitis[108].Importantly, NAFLD-related HCC may develop without liver cirrhosis, with a significantly higher prevalence observed in individuals with noncirrhotic NASH compared to other liver diseases[109].The pathogenesis of HCC in NAFLD involves insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction, triggering the release of free fatty acids and subsequent oxidative stress, along with the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α.Obesity exacerbates this process by inducing chronic inflammation, activating oncogenic transcription factors like STAT3, and fostering gut dysbiosis with hepatocarcinogenesis promotion[110].The transition from NAFLD to MAFLD has highlighted its role as a primary cause of HCC[111].Furthermore,HCC development in MAFLD is closely linked to the degree of fibrosis and can occur in non-cirrhotic livers[112].The recent shift to the terminology of MASLD has prompted a reassessment of HCC risk,revealing higher risks for first-degree relatives of MASLD patients[113].The scientific research has highlighted the role of non-coding RNAs, specifically microRNAs/small regulatory RNAs (miRNAs/miRs), in liver diseases.MiR-21-5p, implicated in MASLD progression to hepatocarcinogenesis, activates peroxisome replication, inducing lipid peroxidation and inflammation-fibrosis.Inhibiting miR-21-5p may offer therapeutic potential in HCC[114].Additionally, gut dysbiosis contributes to HCC by increasing hepatic exposure to bacterial metabolites, activating toll-like receptor-4, and promoting fibrosis, emphasizing the therapeutic potential of gut microbiota modulation[115].Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), an aggressive neoplasm of the bile ducts, accounts for approximately 3%-5% of all gastrointestinal cancers.The prognosis of CCA is poor because 95% of patients die within five years.According to a recent meta-analysis of seven case-control studies, NAFLD was significantly associated with an increased risk of CCA for both subtypes[116].On the other hand, a more recent analysis showed that NAFLD is associated with an elevated risk of both total cholangiocarcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA) but without a significant association with extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (eCCA)[117].Furthermore, CCA arising from NASH patients has a severe prognosis compared to that from NAFLD[118].In recent years, the association between MAFLD and CCA was evaluated.In this regard, emerging risk factors like obesity, T2DM, and MAFLD were primarily associated with iCCA, while traditional risk factors such as biliary cysts, liver cirrhosis, HBV, and HCV infections were associated with both iCCA and eCCA[119].Moreover, a recent study involving 173 patients who underwent liver resection for iCCA found a high prevalence of MAFLD, significantly correlated with changes in body composition such as sarcopenia and visceral obesity[120].The association between MASLD and CCA, especially with iCCA, has been proposed, supported by findings in mice models, demonstrating that MASLD exacerbates cholangitis and iCCA development[121,122].Additionally, overexpression of osteopontin in the tumor stroma of MASLD patients with iCCA has been observed, suggesting its potential as a predictive biomarker and therapeutic target[123].Nevertheless, further studies are needed to elucidate the specific relationship between MASLD and CCA.Hepatic and extrahepatic complications of MASLD have been reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3.Hepatic and extrahepatic complications of MASLD.MASLD: Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver disease, CVD:Cardiovascular Disease; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; CCA: Cholangiocarcinoma; IBD: Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

CONCLUSIONS

MASLD has been defined as SLD with at least one of the five cardiometabolic risk factors without excessive alcohol intake.Furthermore, it is a multi-factorial disease with a significant public health impact.Indeed,risk factors and complications necessitate the involvement of several medical specialists.Moreover, given the recent proposal of this new nomenclature, there is an urgent need to perform further clinical studies on large cohorts of patients.At the same time, future research should implement the use of new diagnostic tools and robust biomarkers for early detection of MASLD, especially in patients at risk.In this regard, the application of new algorithms and artificial intelligence could help in clinical practice.Nevertheless, further evidence is needed to clarify the clinical impact of MASLD in real-world settings.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript: Colaci C, Gambardella ML Provided figures and tables: Colaci C, Gambardella ML

Reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted: Colaci C, Gambardella ML, Scarlata GGM,Boccuto L, Scarpellini E

Read and approved the final manuscript: Boccuto L, Colica C, Luzza F, Scarpellini E, Mendez-Sanchez N,Abenavoli L

Conceptualized and designed the review: Abenavoli L

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.

- Hepatoma Research的其它文章

- The role of percutaneous hepatic perfusion (PHP) in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma

- Role of temporary portosystemic surgical shunt during liver resection to prevent a post-resection small for size-like syndrome

- Progression of liver disease and associated risk of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Reflections and perspectives on adjuvant treatment in the setting of resected hepatocellular carcinoma

- Introduction to 2023 Chinese expert consensus on the whole-course management of hepatocellular carcinoma