Propensity score matching analysis for clinical impact of braided-type versus laser-cut-type covered self-expandable metal stents for endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy

Mitsuki Tomit ,Tkeshi Ogur ,,* ,Akitoshi Hkod ,Sori Ueno ,Atsushi Okud ,Nou Nishiok ,Yoshitro Ymmoto ,Hiroki Nishikw

a 2nd Department of Internal Medicine, Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University, Osaka, Japan

b Endoscopy Center, Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University, Osaka, Japan

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ABSTRACT Background: To prevent stent migration during endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUSHGS),intra-scope channel release technique is important,but is unfamiliar to non-expert hands.The selfexpandable metal stent (SEMS) is an additional factor to prevent stent migration.However,no comparative studies of laser-cut-type and braided-type during EUS-HGS have been reported.The aim of this study was to compare the distance between the intrahepatic bile duct and stomach wall after EUS-HGS among laser-cut-type and braided-type SEMS.Methods: To evaluate stent anchoring function,we measured the distance between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall before EUS-HGS,one day after EUS-HGS,and 7 days after EUS-HGS.Also,propensity score matching was performed to create a propensity score for using laser-cut-type group and braided-type group.Results: A total of 142 patients were enrolled in this study.Among them,24 patients underwent EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type SEMS,and 118 patients underwent EUS-HGS using a braided-type SEMS.EUS-HGS using the laser-cut-type SEMS was mainly performed by non-expert endoscopists (n=21);EUS-HGS using braided-type SEMS was mainly performed by expert endoscopists (n=98).The distance after 1 day was significantly shorter in the laser-cut-type group than that in the braided-type group [2.00 (1.70-3.75) vs.6.90 (3.72-11.70) mm,P < 0.001].In addition,this distance remained significantly shorter in the laser-cut-type group after 7 days.Although these results were similar after propensity score matching analysis,the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach after 7 days was increased by 4 mm compared with the distance after 1 day in the braided-type group.On the other hand,in the laser-cuttype group,the distance after 1 day and 7 days was almost the same.Conclusions: EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type SEMS may be safe to prevent stent migration,even in nonexpert hands.

Introduction

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS)can be indicated for surgically altered anatomy or duodenal obstruction after failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [1-5].EUS-HGS has recently been performed for benign biliary diseases such as hepaticojejunostomy stricture or bile duct stones complicated by an inaccessible papilla [6,7].However,in EUS-guided biliary drainage,EUS-HGS is a highly complex procedure,and critical adverse events such as stent migration into the abdominal cavity can occur [8,9].To prevent stent migration into the abdominal cavity,techniques for stent deployment are important [10],but are unfamiliar to non-expert hands.The selfexpandable metal stent (SEMS) is an additional factor to prevent stent migration.

The SEMS can be mainly divided into two groups: the laser-cuttype and the braided-type.Generally,compared with the braidedtype,radial force is lower in the laser-cut-type.Although this fact may be a disadvantage from the perspective of drainage effect,anchoring function between the bile duct wall and stomach wall is extremely strong [11].Therefore,during EUS-guided biliary drainage,a safe procedure might be more readily achieved for both expert and non-expert hands if a laser-cut-type SEMS is used compared with the braided-type.However,no comparative studies of laser-cut-type and braided-type during EUS-HGS have been reported.The aim of this study was to compare the distance between the intrahepatic bile duct and stomach wall after EUS-HGS among laser-cut-type and braided-type SEMS.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients who underwent EUSHGS using laser-cut-type or braided-type SEMS between April 2014 and February 2022.In this study,patients who underwent EUSHGS due to histologically diagnosed malignant biliary obstruction were enrolled.Patients who had undergone EUS-guided antegrade stenting combined with EUS-HGS or who showed complications of hepatic hilar biliary obstruction were excluded.

All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University (IRB No.2022-088).The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Tips for EUS-HGS and properties of SEMS

An echoendoscope (UCT260;Olympus Optical,Tokyo,Japan)was inserted into the stomach.The intrahepatic bile duct was then punctured using a 19-G needle.After successful bile duct puncture,bile juice was aspirated,and contrast medium was injected to obtain a cholangiography (Fig.1 A).Subsequently,a 0.025-inch guidewire (VisiGlide;Olympus Medical System,Tokyo,Japan) was deployed in the biliary tract (Fig.1 B).The intrahepatic bile duct and stomach wall were dilated using a standard ERCP catheter,4-mm balloon catheter (REN biliary balloon catheter;KANEKA,Osaka,Japan) or ultra-tapered mechanical dilator (ES dilator;Zeon Medical Inc.,Tokyo,Japan).The dilation devices used depend on the decisions of the endoscopist.After tract dilation,stent deployment was performed using the intra-scope channel release technique,as described previously [10].

Fig.1.A: The intrahepatic bile duct was punctured using a 19-G needle.B: A 0.025-inch guidewire was deployed at the biliary tract.C: Stent deployment from the intrahepatic bile duct to the stomach was successfully performed.

In this study,braided-type (S-type or Spring Stopper,8 or 10 mm × 12 cm;TaeWoong Medical Co.,Seoul,Korea) (Fig.1 C)and laser-cut-type (BileRush Advance,8 mm × 12 cm;Piolax Medical,Kanagawa,Japan) EUS-HGS stents were used.The diameter of the braided-type stent delivery system was 8.5 Fr with a 1-cm-long uncovered site.On the other hand,diameter of the laser-cut-type stent delivery system was 7.0 Fr with a 2-cm-long uncovered site.The endoscopist attempted to insert a laser-cut-type stent into the biliary tract without tract dilation because of the fine gage of the stent delivery system.

Definitions

In this study,an expert endoscopist was defined as one who had performed>32 EUS-HGS procedures,as previously described [12].Procedure time was measured from echoendoscope insertion to successful stent deployment.Intraoperative bleeding events were defined as puncture-site hematoma,representing continuous bleeding needing endoscopic and/or intravenous and/or surgical hemostasis around the puncture site.Bile peritonitis was diagnosed if fever,elevated inflammatory markers on blood examination,and abdominal pain were observed within 1 day after EUS-HGS.Bile peritonitis was also diagnosed from findings of bile leakage or peritonitis around the HGS stent according to computed tomography (CT) performed the day after EUS-HGS.Stent patency was measured from stent deployment to stent dysfunction or death of the patient.Stent dysfunction was considered present if jaundice recurred with clinical imaging findings such as biliary dilatation or cholangitis.Adverse events associated with EUS-HGS procedures were evaluated according to the severity grading system of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy lexicon [13].

In our hospital,all patients underwent CT one day after EUSHGS as clinical practice.After around 7 days,all patients underwent CT to evaluate late adverse events such as bile leakage,stent migration,or dislocation.

To evaluate stent anchoring function,we measured the distance between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall before EUSHGS,one day after EUS-HGS,and 7 days after EUS-HGS (Fig.2).

Fig.2.A: Distance between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall was 20.55 mm on computed tomography.B and C: The distance was 5.86 mm at 1 day after EUS-HGS(B),and 15.71 mm at 7 days after EUS-HGS (C).EUS-HGS: endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed mainly using SPSS version 13.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc.,Chicago,IL,USA).Data were corrected as average values after five measurements by three doctors.Descriptive statistics were presented as median and range for continuous variables and frequency for categorical variables in the laser-cut-type SEMS and braided-type SEMS groups.The two groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test.Propensity score matching was performed to create a propensity score for the lasercut-type group and braided-type group with a logistic regression model.One-to-one matching without replacement was performed with a 0.2 caliper width,and the resulting score-matched pairs were used in subsequent analysis.Patients were adjusted for 5 factors including age,sex,primary disease,reason for EUS-HGS,and puncture site.AP <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

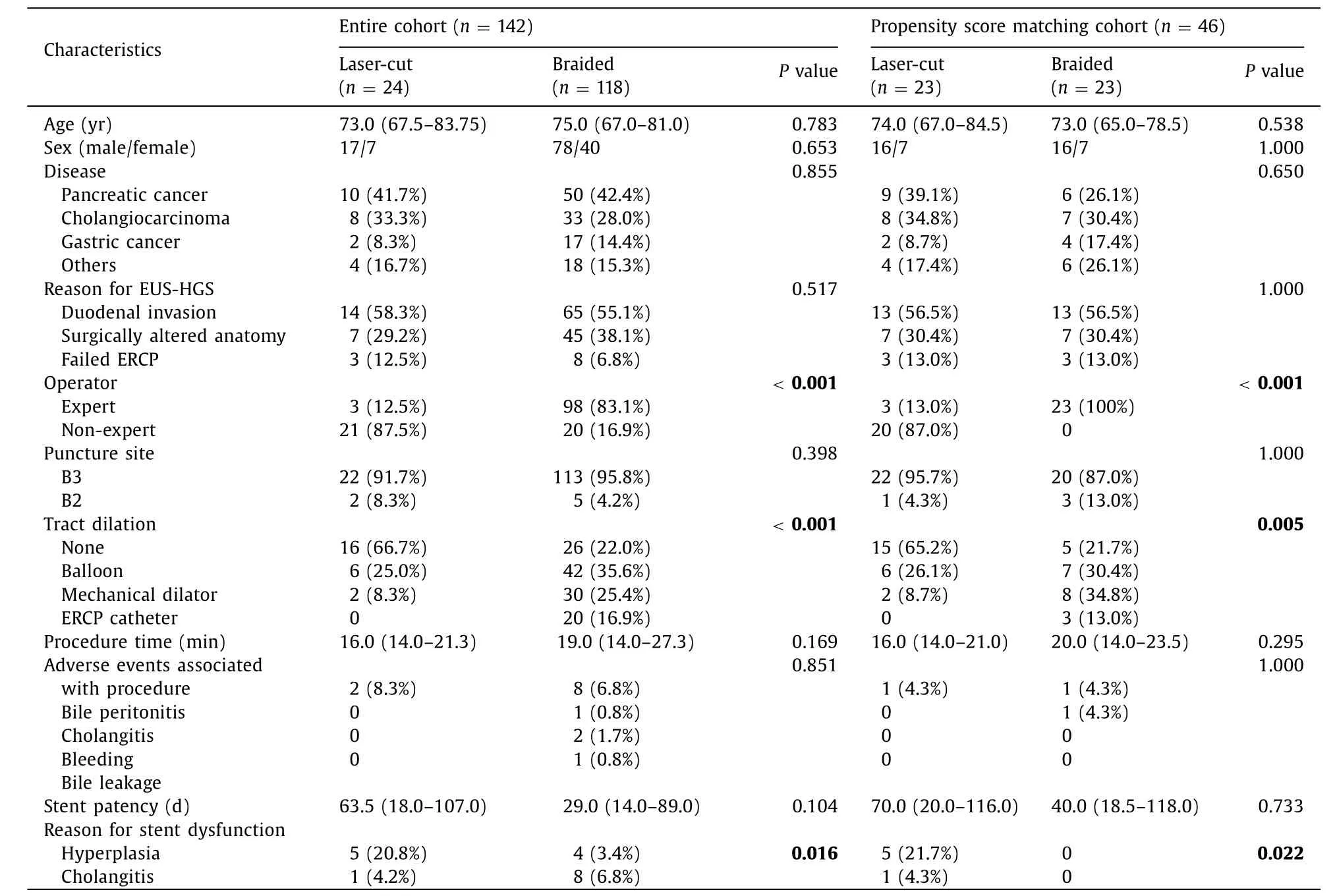

A total of 142 patients were enrolled in this study.Among them,24 (median age,73.0 years;17 males) underwent EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type SEMS,and 118 (median age 75.0 years;78 males)using a braided-type SEMS.Table 1 shows patient characteristics.Primary cancers in this study were mainly pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma,with no significant differences between the two groups (P=0.855).The main indication for EUS-HGS was duodenal invasion or surgically altered anatomy and no significant differences were seen between the two groups for this factor(P=0.517).

Table 1Patient characteristics.

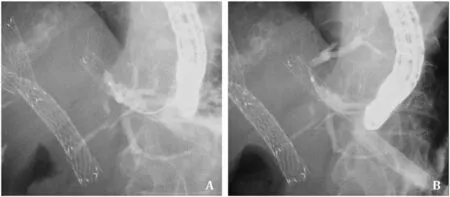

EUS-HGS using the laser-cut-type SEMS was mainly performed by non-expert endoscopists (n=21) and braided-type SEMS mainly by expert endoscopists (n=98,P <0.001).Regarding procedural details,the puncture site was mainly B3,with no significant differences between the two groups (P=0.398).The rate of EUS-HGS without tract dilation was significantly higher in the laser-cut-type group (66.7%,16/24) compared with the braidedtype group (22.0%,26/118;P <0.001).However,median procedure time between the two groups [laser-cut-type,16.0 (14.0-21.3)min;braided-type,19.0 (14.0-27.3) min]was not significantly different (P=0.169).As adverse events,bile peritonitis,cholangitis,bleeding,and bile leakage were observed,but the rate of adverse events did not differ significantly between groups (P=0.851).Stent dysfunction was observed in 6 patients among the laser-cuttype group,and 12 among the braided-type group.Compared with the braided-type group,stent dysfunction due to hyperplasia was frequently observed in the laser-cut-type.Re-intervention was successfully performed in all except one patient.This patient underwent EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type SEMS.However,stent dysfunction was observed due to hyperplasia (Fig.3),but guidewire passage into the biliary tract failed across this site.This patient therefore underwent transhepatic biliary drainage.Median stent patency did not differ significantly between the two groups [lasercut-type,63.5 (18.0-107.0) days vs.braided-type,29.0 (14.0-89.0)days;P=0.104].

Fig.3.A: After EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type self-expandable metal stent,stent obstruction due to mucosal hyperplasia at the uncovered site was observed.B: The guidewire cannot be advanced into the intrahepatic bile duct through the obstruction site.EUS-HGS: endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

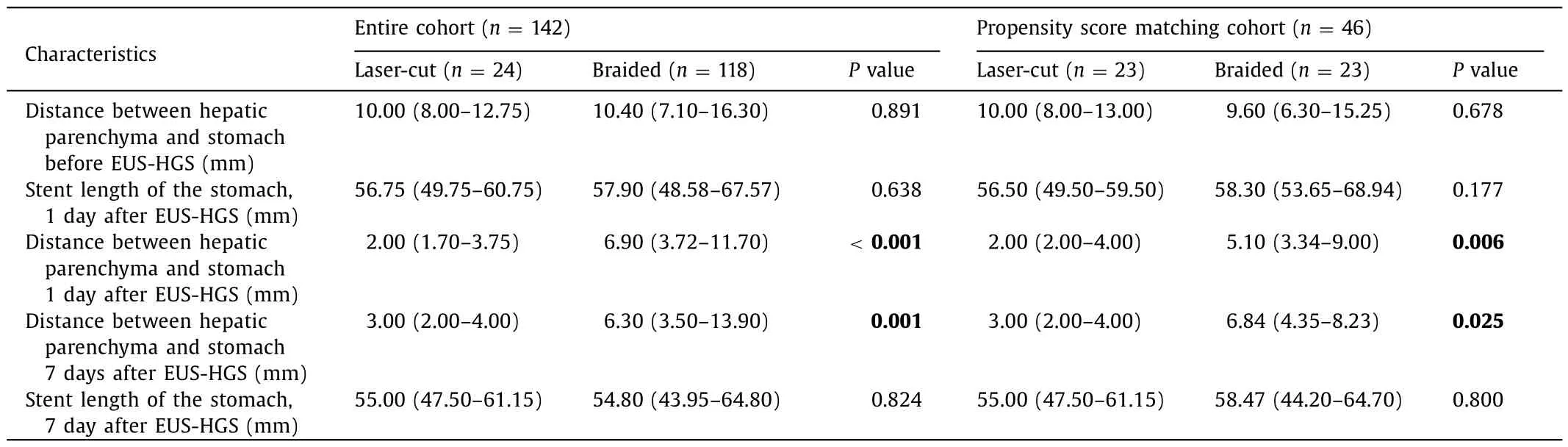

Table 2 shows the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall before EUS-HGS,and 1 and 7 days after EUS-HGS between the two groups (typical case as shown in Fig.4).Although the median distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall before EUS-HGS did not differ significantly between groups[laser-cut-type,10.0 0 (8.0 0-12.75) mm;braided-type;10.40 (7.10-16.30) mm;P=0.891],the median distance after 1 day was significantly shorter with the laser-cut-type group [2.00 (1.70-3.75) mm] compared to that in the braided-type group [6.90 (3.72-11.70)mm;P <0.001].In addition,this distance remained significantly shorter in the laser-cut-type group than that in the braided-type group after 7 days [3.00 (2.00-4.00) mm vs.6.30 (3.50-13.90) mm,P=0.001].Although these results were similar after propensity score matching analysis,the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach after 7 days was increased by 4 mm compared with the distance after 1 day in the braided-type group.On the other hand,in the laser-cut-type group,the distance after 1 day and 7 days was almost the same.Finally,the stent length of the stomach was not significantly different between two groups after 1 day and 7 days.

Table 2Results of the procedure.

Fig.4.A and B: Distance between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall is 12.46 mm at 1 day after EUS-HGS (A),and 29.3 mm at 7 days after EUS-HGS (B)in the braided-type group.C and D: Distance between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall is 6.88 mm at 1 day after EUS-HGS (C),and 7.71 mm at 7 days after EUS-HGS (D) in the laser-cut-type group.EUS-HGS: endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy.

Discussion

EUS-HGS is now widely performed as an alternative biliary drainage technique for failed ERCP,and also for benign biliary disease.EUS-HGS therefore has clinical impact.However,adverse events such as stent migration into the abdominal cavity are sometimes fatal.To prevent stent migration into the abdominal cavity,various techniques and effort s have been reported [10,14-16].Cho et al.reported the long-term outcomes of a hybrid metal stent for EUS-guided biliary drainage [16].In this study,the stent was immobilized by anchoring flaps on the distal and proximal portions,helping to reduce the risk of stent migration.Indeed,stent migration was not observed in any of the 21 patients who underwent EUS-HGS using this novel stent.However,even if this stent was used for EUS-HGS,stent migration can still occur [9].Recently,several authors have described effective techniques,such as the ClipFlap anchoring method [14],or Crisscross anchor-stents technique [15],to prevent stent migration into the abdominal cavity.Although these reports may have clinical impact,the procedure itself may be complex.In addition,a risk of stent dislocation or migration may arise during these procedures because a fistula between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall is not formed.According to our previous findings,at least 7 days may be needed to create a fistula between the hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall [7].

As significant findings,Ochiai et al.evaluated risk factors for stent migration into the abdominal cavity during EUS-HGS using braided-type SEMS [8].They enrolled 48 patients.Stent migration was observed in 5 patients (one actual,four imminent).Initial distance between the puncture site and stomach was significantly shorter in the non-stent migration group(20.1 ± 12.8 mm) compared to that in the stent migration group(47.0 ± 11.3 mm).Distance between the stomach and liver at the puncture site was significantly shorter in the non-stent migration group (17.7 ± 9.8 mm) compared to that in the stent migration group (44.8 ± 10.7 mm).They therefore concluded that a longer distance between the stomach and liver at the puncture site increased the risk of stent migration.However,prediction of the puncture site is not easy,as the puncture site may change according to stomach,volume of the hepatic parenchyma to prevent bile leakage [17],or stiffness of the echoendoscope or fine needle.Recently,a novel SEMS with an anti-migration system (Spring stopper stent;Taewoong Medical Co.,Seoul,Korea) has been available in Japan.However,Koga et al.described a case of stent dislocation during EUS-HGS using that novel stent [18].The patient in that case underwent surgical recovery,and the stent could not be pulled out of the stomach wall during surgery.This stent thus has strong anti-migratory function.Although this fact is encouraging,if the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall is long,the risk of not only stent migration into the abdominal cavity but also stent dislocation should be considered.

According to these previous studies,certain anchoring functions of the body of SEMS wall may be important to prevent stent migration.In our study,two significant findings were observed.First,after EUS-HGS,the anchoring function of the laser-cut-type SEMS,which could be explained by the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall,was significantly shorter compared with braided-type SEMS on days 1 and 7 after EUS-HGS.Compared with the braided-type SEMS,radial force is normally low,potentially creating a strong anchoring function at the hepatic and stomach sites.This might suggest that stent migration into the abdominal cavity may be unlikely not only during EUSHGS,but also after successful stent deployment.In addition,despite that the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach wall of the laser-cut-type SEMS was significantly shorter than that in the braided-type SEMS group on days 7 after EUS-HGS,stent length of the stomach on days 7 after EUS-HGS was not significantly different between the two groups.This discrepancy might occur for the following reasons.Because anchoring force might be lower in braided-type SEMS,stent dislocation toward stomach side may easily occur compared with that in laser-cut-type SEMS.Also,stent shortening within stomach lumen might be influenced during stent full expansion.Second,compared with the braided-type SEMS group,EUS-HGS with a laser-cut-type SEMS was mainly performed by non-experts,yet neither procedure time nor rate of adverse events differed significantly between groups.This might be explained by the following phenomenon.First,the stent delivery system for the laser-cut-type SEMS was fine gage compared with that for the braided-type SEMS,and therefore,tract dilation may not be needed in the majority of cases.Moreover,the distance between hepatic parenchyma and stomach on day 7 after EUS-HGS was increased in the braided-type group although the distance in the laser-cut-type group was the same.This fact may be associated with delayed stent migration in the braided-type.Second,because of the strong anchoring function,stent migration was unlikely even for EUS-HGS performed by a non-expert.Compared with laser-cuttype SEMS,braided-type SEMS may have weaker anchoring on the liver side,and stent dislocation may easily occur.On the other hand,stent patency was lower in the laser-cut-type SEMS compared to that in the braided-type SEMS,although the difference was not significant.In addition,re-intervention could not be performed in one case from the laser-cut-type SEMS group due to mucosal hyperplasia.This may be due to the site of the laser-cut-type SEMS remaining uncovered for a prolonged period.A 1-cm uncovered site of EUS-HGS stent may be sufficient to prevent stent dislocation or prevent obstruction of the bile branch duct.

The present study had several limitations,including the retrospective design,small sample size,and single-center nature.Randomized controlled trials are necessary to validate our results.

In conclusion,EUS-HGS using a laser-cut-type SEMS may be safe to prevent stent migration,even in non-expert hands,compared with a braided-type SEMS.

Acknowledgments

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mitsuki Tomita:Data curation,Formal analysis,Resources,Software,Supervision,Validation,Visualization,Writing -original draft,Writing -review &editing.Takeshi Ogura:Formal analysis,Investigation,Writing -original draft.Akitoshi Hakoda:Formal analysis,Supervision.Saori Ueno:Writing -review &editing.Atsushi Okuda:Writing -review &editing.Nobu Nishioka:Writing -review &editing.Yoshitaro Yamamoto:Writing -review &editing.Hiroki Nishikawa:Writing -review &editing.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University (IRB No.2022-088).

Competing interestNo benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2024年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2024年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Editors

- Information for Readers

- Meetings and Courses

- Liver transplantation and liver resection as alternative treatments for primary hepatobiliary and secondary liver tumors: Competitors or allies?

- Laparoscopic anatomical liver resection of segment 7 using a sandwich approach to the right hepatic vein (with video)

- Severe liver injury and clinical characteristics of occupational exposure to 2-amino-5-chloro-N,3-dimethylbenzamide: A case series