景观—社会学视角下的北京高密度城区儿童游戏专属和发现空间

(英)海伦·伍利 汤湃*

1 研究背景

近年来,为儿童提供游乐场的重要性在世界范围内得到广泛认同。然而,也有一些与此相悖的观点不断出现。其中尤其值得注意的是长期观察儿童活动的研究者的主张,如Opie等在1969年提出“儿童在哪里,他们就在哪里玩”,社会学研究认为“玩耍是儿童的天性”[1-3],这些观点与“儿童专属游乐场对于儿童成长至关重要”这一传统理念相悖。

1.1 儿童专属游戏场地的起源

纵观儿童游乐场的发展历程可以发现,在19世纪以前,世界范围内许多国家都没有儿童专属的游乐场,儿童自由自在地在各种地方进行游戏和户外活动。17世纪末中国清代宫廷画家杨晋的绘画作品《百子戏图》生动地表现了儿童运用各种场地自由玩耍的场景;同样,1560年彼得·勃鲁盖尔绘制的作品《儿童游戏》中也生动地展现了不拘于地点的儿童游戏的丰富性。而如今,随着游乐场的发展,在儿童游乐场广泛分布的背景下,儿童随处玩耍的现象仍然普遍存在。在世界范围内,游乐场真正成为儿童游戏的重要空间始于19世纪下半叶。游乐场能够有效促进儿童心理和身体健康发展[2]并为儿童提供远离负面社会影响的安全场所[4],因此得以蓬勃发展。在此之后,20世纪初汽车逐渐成为城市家庭的主流交通方式,引发了大量交通问题,这种对于交通安全问题的担忧从20世纪30年代[5]持续至21世纪[6-10]。在这样的背景下,儿童的户外游戏面临交通安全隐患的影响,为应对城市现代化发展对儿童生活带来的负面影响,给儿童提供更加安全的户外游戏环境,一些国家制定了政策以促进儿童游乐场的建立。例如英格兰地区1859年颁布了《休闲场地法案》(Recreation Grounds Act),允许划定一部分城市公共空间仅供儿童游玩[11]。这些对于城市发展问题导致弱势群体受到不良影响的反思为儿童专属游戏场地的发展提供了契机。

1.2 儿童专属游戏场地的发展

在儿童专属游戏场地发展的最初阶段,活动空间被高围栏围合,仅设有体育锻炼器材。之后才逐渐使用了更为丰富多样的设计方法。英国皇家风景园林学会的第一位院士艾伦夫人(1897—1976)根据不同游乐场的环境特点和建筑材料,将游乐场的发展时代主要划分为混凝土时代和迷宫时代。这些不同时代的游戏场地反映了“二战”后混凝土作为一种新型建设材料的日益普及。20世纪下半叶,儿童游乐场引入了新的材料,例如色彩鲜艳的钢铁器械和橡胶铺装,取代了混凝土设施和柏油铺装,尽管围栏仍然存在,但也逐渐变矮和更丰富多彩。儿童游乐场设置围栏的最初目的是防止狗进入,后来逐渐演变成将儿童限制在特定区域,最后发展至伍利等学者描述的“工具、围栏、地毯”(KFC)模式——单一且固化的游乐场空间[12];此外,其他形式的儿童专属游戏场地还包括幼儿园的游戏场地、学校操场以及滑板公园等。虽然KFC模式的游乐场地承载儿童多样游戏的能力十分有限,但至今仍是儿童游戏场地设计的主流方式。而对于高密度城市而言,低承载能力的公共场地被视为是对城市宝贵公共空间资源的浪费。因此,以科学的方法提升城市公共空间服务效能,尤其是专属于特定人群的活动空间的服务效能是实现可持续城市发展的有效方式。

1.3 儿童发现空间概念

以儿童会在任何地方进行游戏且游戏是儿童的天性为理论基础,更多研究认为任何形式的儿童专属游乐场都无法完全满足儿童日常生活中丰富多样的游戏需求。自20世纪60年代以来,彼得·欧皮、艾欧娜·欧皮、科林·沃德、罗杰·哈特、罗宾·摩尔等研究者观察到儿童在特定的游乐场区域以及不为儿童专属的公共空间进行游戏,并称后者为“发现空间”[13]。例如,当城市公共空间中常见的楼梯坐人时,即可被视为一种发现空间,因为楼梯的原始功能是上下通行而非停留和就座。因此,儿童发现空间可定义为:功能设定并非儿童游戏,但被儿童用于游戏的空间和场所。现有研究中记录的儿童发现空间包括机动车道、人行道、停车场、野生动物区、种植区、围墙、围栏和屋顶等。

1.4 以可供性理论为基础的儿童发现空间研究

可供性理论从一定程度上解释了儿童使用发现空间进行户外活动的原因。该理论由吉布森于1986年提出,核心理念是强调个体可以感受到环境所提供的行为潜力,并通过行为活动与环境进行互动[14]。这种对于环境的感知受个体特征以及个体与环境互动方式差异的影响。因此,从对个体行为的作用程度角度来看,可供性可以细化为2个层面:潜在的可供性与已实现的可供性,二者取决于个体是否意识到潜力并采取行动[15]。在后续发展中,可供性理论不仅用于解释环境影响儿童行为的方式[16-18],也用以评估场地对于儿童行为的支持和抑制作用[19-21]。因此,在本研究中,可供性理论也用于解释儿童对于日常生活中多种空间场地的使用偏好。

基于以上背景,本研究聚焦在中国高密度城区中成长的儿童如何使用日常生活中的各类空间。自20世纪80年代以来,中国经历了快速城市化发展,城市人口数量激增,有限的城市户外公共空间愈发难以满足不同年龄段城市居民对于多样户外活动的需求,提升户外公共空间的服务能力成为解决方法之一。不仅如此,2021年颁布的“十四五”规划首次将“建设儿童友好型城市”正式写入国家发展规划[22];同年10月发布的《关于推进儿童友好城市建设的指导意见》提出在全国范围内开展100个儿童友好城市建设试点的发展目标[23]。实现这些儿童友好城市建设目标的方法不仅在于为儿童建设更加丰富的游乐场,更在于为儿童营造更加包容友好的日常生活环境。

然而,关于城市儿童如何使用日常生活中各类公共空间的研究尚不足。因此,本研究以北京市高密度城区为例,探究儿童对日常生活中各类户外空间的使用情况和儿童使用各类空间环境的行为动机,探讨更加高效的儿童友好环境营建方法,为创建针对中国城市环境特征的儿童友好环境提出更加科学的建议。

2 研究方法

2.1 研究设计

基于研究目标,本研究重点关注3个方面的问题:1)儿童日常进行游戏的户外场所包括哪些专属空间和发现空间?2)儿童为什么选择发现空间进行游戏?3)如何改进整体环境以提升儿童的户外游戏体验?为此,采用景观—社会学视角,主要通过社会学研究方法进行数据收集,并且依据多源数据对现象进行描述,在此基础上对现象的形成原因进行解释[24]。因此,研究方法分为2个步骤:首先,通过与儿童的访谈和交流了解他们日常的户外游戏方式及进行户外游戏的空间和场所,对高密度城区中儿童户外空间的使用现象进行归纳;其次,选取儿童经常提到的户外活动场地进行行为观察,记录儿童的游戏活动方式和场地特征,解释环境对儿童户外活动方式的影响机制。这样不仅可以对环境特征影响儿童户外游戏方式的机制进行深入探究,也可以为探讨高密度城区更加高效的户外公共空间营造提供更多基于科研数据的解决策略。

2.2 研究区域

本研究选择兼具代表性和特殊性的北京市什刹海周边区域进行案例研究。什刹海区域作为著名的历史文化保护区,区域内施行了保护整治和有机更新相结合的发展策略,历史风貌得以维护;与此同时,随着城市化带来的大规模人口流动,区域内的常住人口与日俱增。在建设管控和人口涌入的共同作用下,什刹海地区逐渐形成了低层建筑、窄街道、高密度人口的空间环境特征。在这样的环境中,传统建筑及其周围有限的半公共和公共户外空间难以满足居民的日常户外活动需求,成为该区域人居环境质量提升面临的重要问题。

经过前期的走访调研发现,公园为什刹海区域的居民户外活动提供了更多的场地,在日常生活中起着非常重要的作用。什刹海区域有3个公园,其中北海公园和景山公园作为皇家园林的代表,是北京市的地标之一,每年吸引数百万游客前往参观;不仅如此,这2个公园为居住在高密度中心城区的居民提供了宝贵的绿地空间进行户外活动。除此之外则是规模较小的后海公园,与熙攘的旅游景点不同,这个公园为周围的居民提供了一个更为安静和日常的环境进行休闲和户外活动(图1)。

2.3 数据收集

本研究采用访谈和观察相结合的方式进行数据收集,利用两种方法的优势,综合提高研究结果的准确性,有助于更加全面地理解复杂的社会现象。

大量研究表明面对面的半结构化访谈更有利于准确理解儿童的表达,与儿童更深入探讨他们特定行为的潜在动机,是针对儿童群体更为可靠且有效的数据收集方法。为了适应儿童的理解和表达能力,访谈采用了多种特殊形式,包括一对一访谈、焦点小组访谈和照片访谈。其中,一对一访谈和焦点小组访谈是基础数据收集方法,照片访谈是了解儿童日常环境使用情况的主要数据收集方法,在行为和健康研究中广泛使用,可以有效记录和表达个体对场所的体验和感知[25-26]。根据萨顿-布朗[27]提出的操作流程,本研究的照片访谈主要包括以下步骤:首先,在社区组织的暑期夏令营中招募参与儿童,并向参与儿童提供数码相机以拍摄他们日常游戏环境的照片(时长为3 d);接下来,研究人员与儿童一起查看照片并就照片内容进行访谈。整体来说,在调研中共有131名6~12岁儿童参与了一对一访谈或者焦点小组访谈(男孩56人,女孩75人);这些儿童中表达能力更好、更年长的儿童自愿选择参加了后续的照片访谈,共有20位8~12岁儿童参与了照片访谈,其中每个年龄均有2位男孩和2位女孩。

行为观察可以最大限度地减少主观表达和实际行为之间存在的差异。因此,行为观察被广泛用于记录真实环境中的行为方式[28]。为了更准确地记录不同场地上发生的多样化儿童游戏活动,通过系统的行为观察记录儿童在户外空间的行为特征。在开始行为观察之前,首先对后海公园进行了实地测量,并将公园划分为2个区域,以便即时记录儿童的活动;在观察期间,在地图上用不同的符号区分男孩和女孩,并在附加的表格里记录儿童的年龄和游戏活动详情。在每个观察区域内,连续观察记录5 min,期间每个儿童的游戏活动仅记录一次。行为观察在每天17:00—19:00进行,历时8天(包括4个工作日和4个周末),共计8次观察。

2.4 数据分析

为全面了解儿童的户外游戏体验,数据分析分为2个阶段。1)分析访谈所收集的定性数据。访谈的音频记录数据在转录和翻译后,利用Nvivo 12软件对访谈内容进行语义分析。此外,将儿童拍摄的照片以及儿童对照片提供的内容阐释也整合到Nvivo 12中进一步分析。这些由访谈收集的定性数据共同形成了本研究的基础质性数据库。2)通过行为观察数据探索公共开放空间的可供性。在行为观察数据收集过程中,每个儿童及其行为方式以不同的符号标记在地图上,可通过ArcGIS可视化分析,探究空间模式与儿童活动之间的关系。这2个阶段的数据分析相辅相成,为深入了解儿童户外游戏行为及其空间环境的影响作用提供了可靠方式。

3 研究结果

3.1 儿童日常生活范围内户外公共空间使用情况

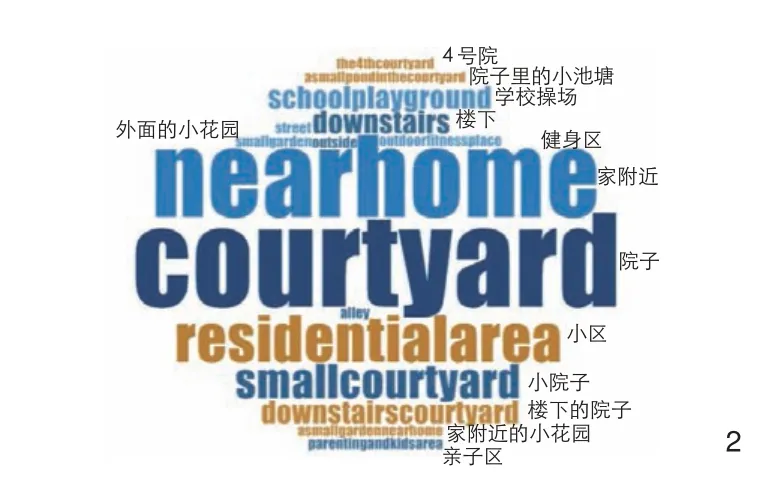

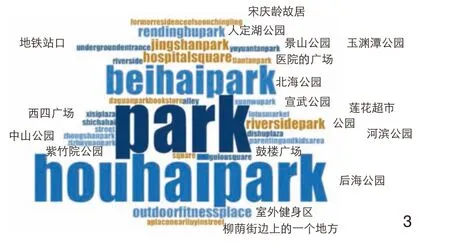

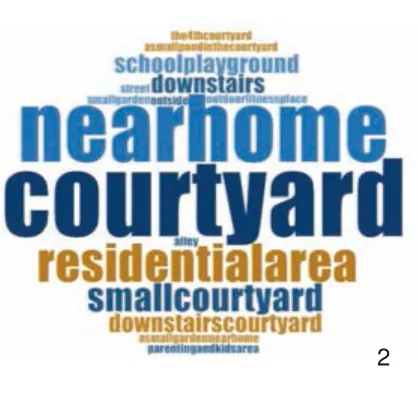

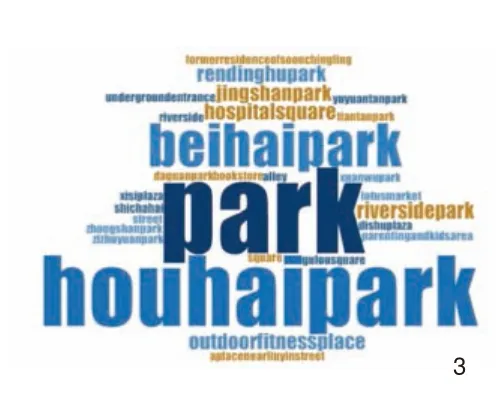

访谈数据显示儿童在日常生活中利用各种各样的户外空间进行活动。丰富多样的户外活动场地一定程度上反映了儿童户外环境使用体验的多样性。词频分析显示,在居住区内,儿童经常进行户外活动的区域包括庭院、家附近的空地、公共空间以及学校操场(图2)。稍远一些但步行可达的生活圈里,公园承载了更多的儿童户外活动,如研究区域内的后海公园和北海公园,是儿童更经常使用的户外活动场地(图3)。词频分析展示了儿童户外游戏的空间偏好,揭示了儿童日常生活圈里的公共空间在承载儿童户外活动方面的重要性。

图2 居住区范围游戏场地词频分析Word frequency analysis of spaces for play in close-tohome outdoor environment

图3 生活圈游戏场地词频分析Word frequency analysis of spaces for play in further outdoor environment

3.2 居住区范围的专属空间和发现空间

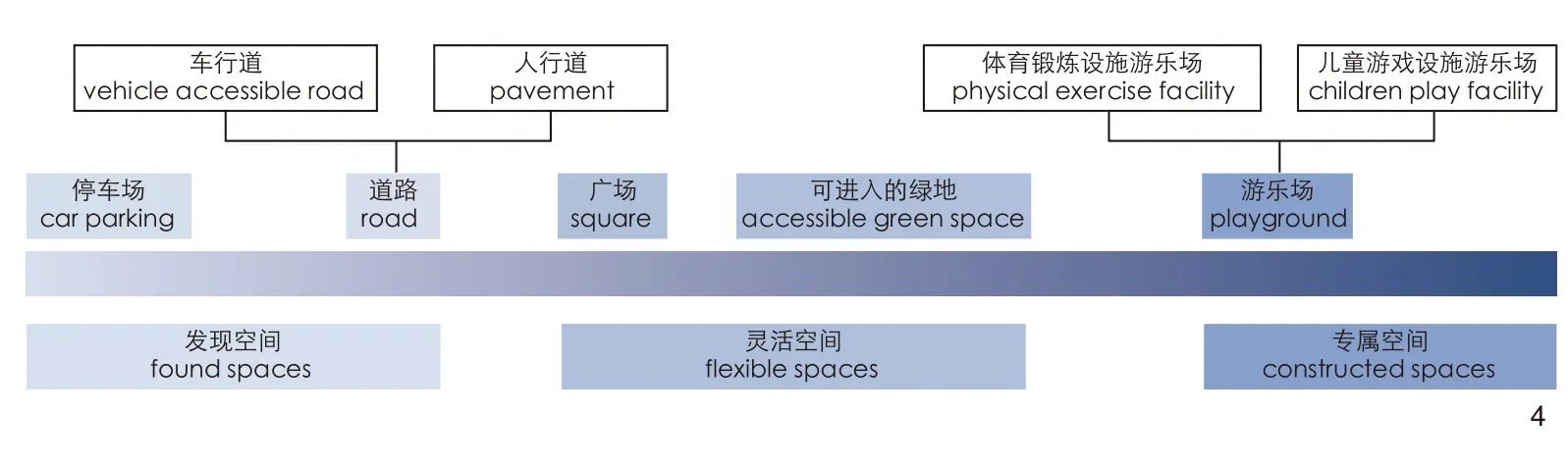

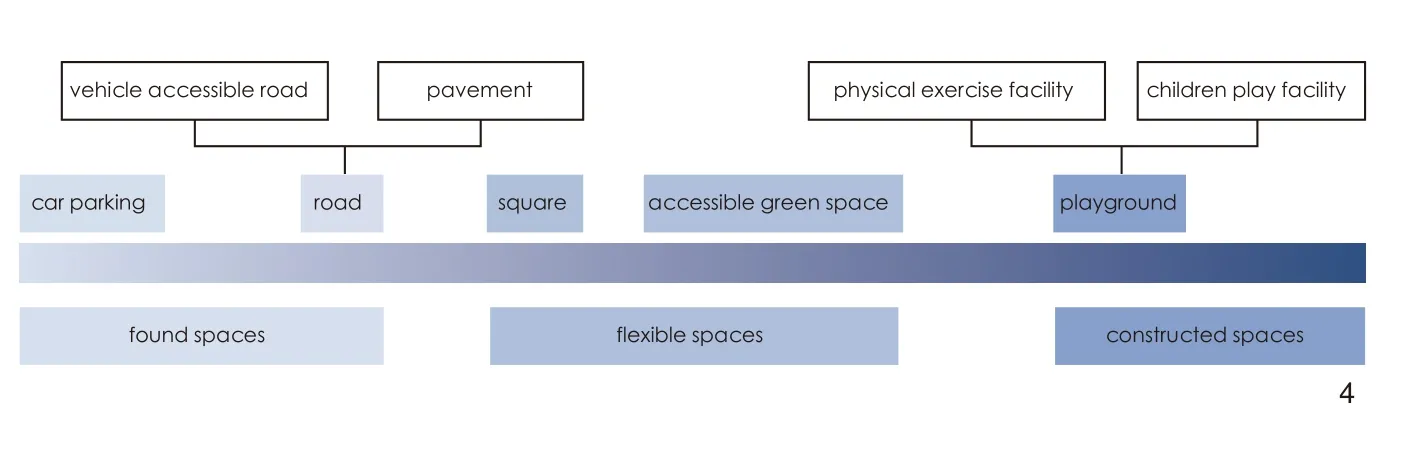

通过儿童拍摄的照片可以了解到,高密度城区的儿童户外活动空间十分有限,他们在居住区附近的各种空间中进行游戏。根据这些空间建设的原始目的,可分为专属空间和发现空间(图4)。

图4 居住区范围的专属和发现空间Constructed and found spaces in close-to-home outdoor environment

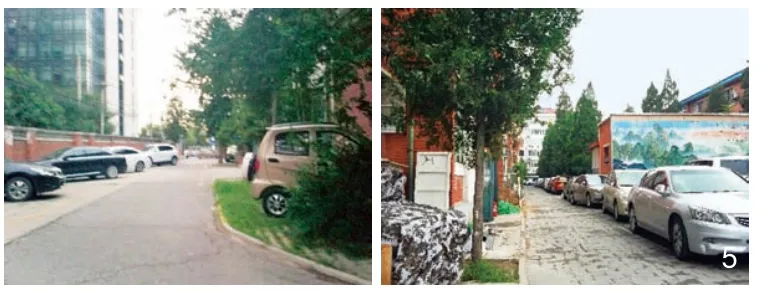

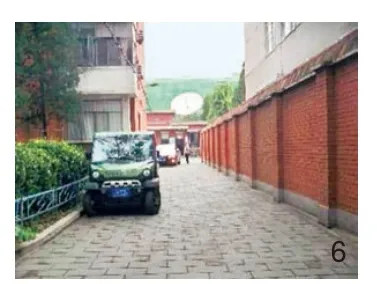

3.2.1 停车场和道路作为发现空间

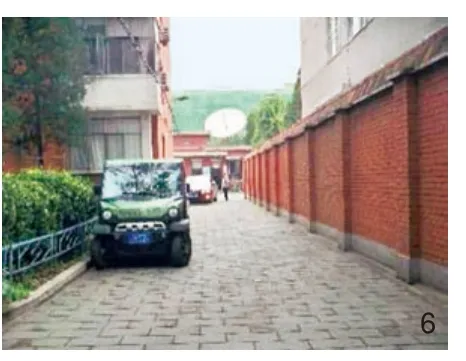

在儿童日常活动范围内,停车场是最经常成为承载儿童户外游戏的发现空间(图5),其次是居住区内通车的道路(图6)和人行道(图7)。相较于车行道,人行道更加适宜儿童进行户外活动,因为没有车辆带来的安全隐患并且能够与社区绿化所提供的自然元素互动。因此本研究认为社区人行道在为儿童提供户外游戏空间以及提供儿童与自然互动的机会方面有更好的作用和效果,提升居住区公共绿地和社区的人行道设计可以为儿童提供更多日常户外游戏场地。

图5 儿童拍摄的停车场作为户外活动场地的照片Photos taken by children showing car parking as play spaces

图6 由儿童拍摄的车行道路作为户外活动场地的照片Photos taken by children showing vehicle accessible road as play spaces

图7 由儿童拍摄的步行道路作为户外活动场地的照片Photos taken by children showing pavements as play spaces

3.2.2 广场和绿地作为灵活空间

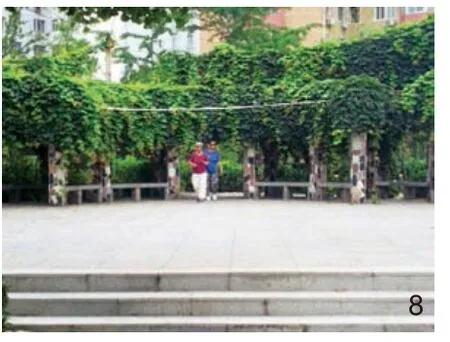

居住区内的广场作为人行道的延伸,为全龄人群的户外活动提供了空间。对于儿童来说,这些广场可以进行包括踏板车骑行、球类游戏、追逐和奔跑等较高强度的体力活动(图8)。但这些公共空间并非儿童专属,不同年龄阶段的人群在共享使用场地时,有不同的偏好和需求,活动时间的重叠在一定程度上可能导致不同年龄群体的活动内容互相影响。尤其对于儿童而言,广场虽然为户外体力活动提供了空间,但由于广场并非儿童专属,在与年长的住区居民共享使用广场时,儿童在一定程度上会处于弱势地位。

图8 由儿童拍摄的广场作为户外活动场地的照片Photos taken by children showing squares as play spaces

此外,在居住区内可进入的绿地同样是儿童会使用的游戏空间(图9)。这些绿地为城市儿童提供了与自然元素互动的宝贵机会,无论是叶子、花朵、土壤还是沙子,这些的自然元素被儿童视为有趣和愉悦的游戏体验。

图9 由儿童拍摄的绿地作为户外活动场地的照片Photos taken by children showing squares as play spaces

3.2.3 游乐场作为专属空间

在儿童的日常生活范围内儿童专属的游戏空间主要包括配备有体育锻炼设施或游戏设施的游乐场(图10)。这些游乐场的建造目的主要是促进和承载儿童的户外游戏,虽然一些游乐场配备的主要是为成年人提供的体育锻炼设施,但这些空间也吸引了大量儿童并被儿童视为为他们建造的户外活动场地。

图10 由儿童拍摄的有体育锻炼设施或游戏设施的游乐场照片Photos taken by children showing playground with physical exercise facilities and play facilities as play spaces

整体来说,照片访谈收集的数据展现了儿童在日常生活范围内对户外空间的多样化利用情况。从停车场中的非正式游戏空间到专属儿童的户外游乐场,其多样化的场地和设施,为儿童的户外游戏提供了不同程度和层次的机会。虽然只有部分空间更适合儿童进行户外游戏,较多空间存在缺陷甚至安全隐患,但对于居住在北京市中心地区的儿童而言,这些已然是最易接触到的户外空间了。

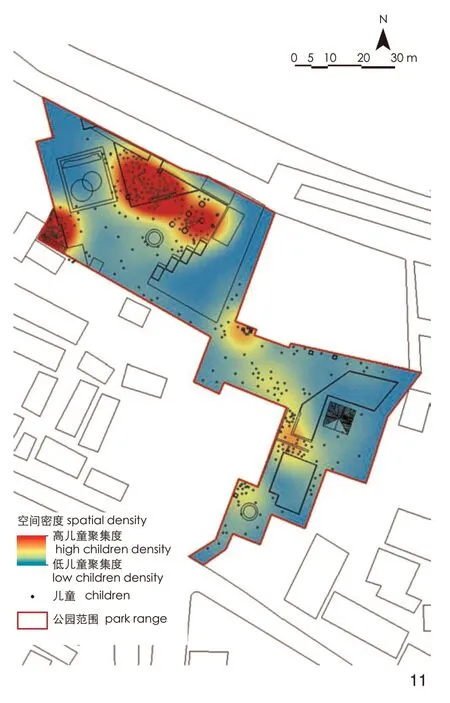

3.3 公园中的专属空间和发现空间

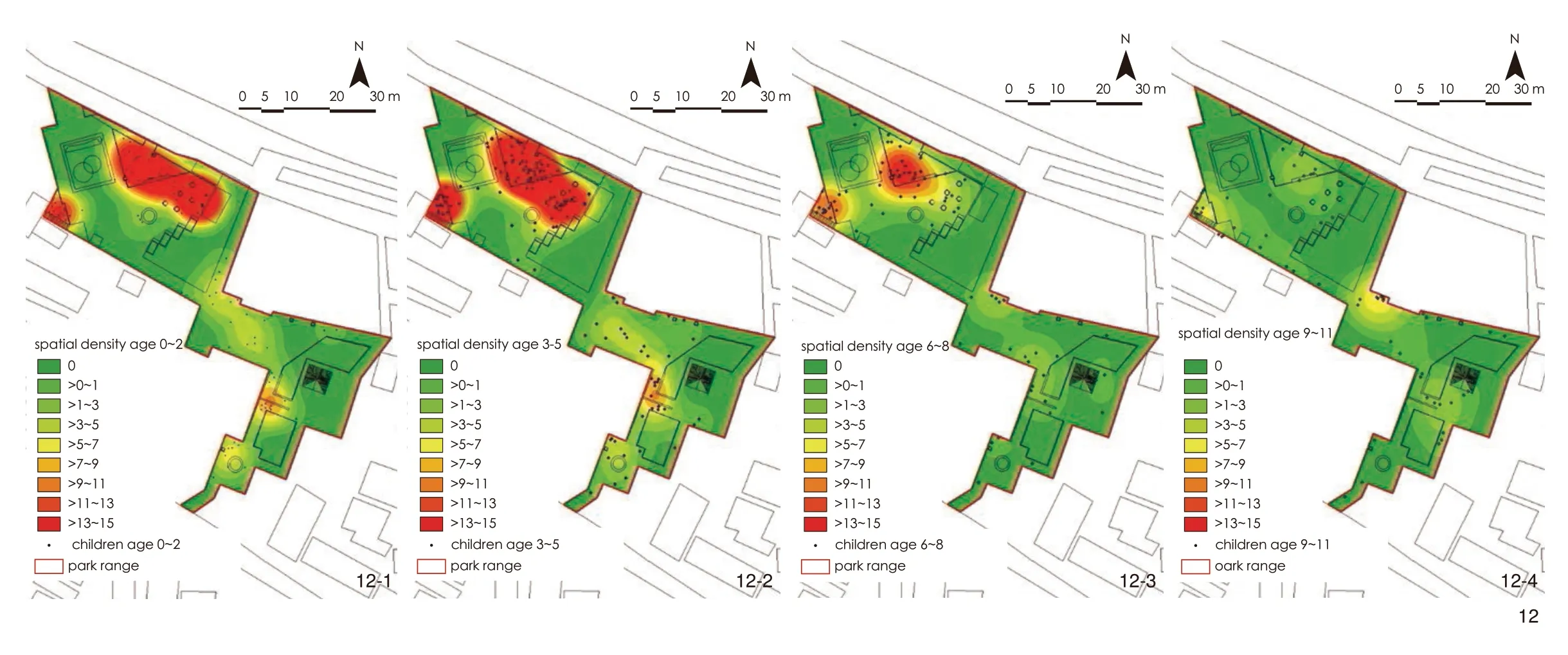

依据访谈结果,后海公园是研究区域儿童最喜爱的户外活动场地之一(图3)。根据在该公园进行行为观察得到的数据,公园所有空间中最受儿童欢迎的游戏场地是2个铺设了橡胶地垫的游乐场以及有树荫遮蔽的硬质铺装小广场。其中,铺设橡胶地垫的游乐场为儿童提供了平坦的开敞空间,适宜进行追逐奔跑等活动;而硬质广场则为儿童提供了更为安静的空间,适宜进行静态游戏。此外,硬质广场东侧角落设置有摇摇车等简单的游乐设施,深受低龄儿童的喜爱,象棋桌则吸引了一些年长儿童。除了这些专属空间,公园不同区域连接处的斜坡则适于进行骑自行车、滑滑板和轮滑等活动(图11)。这些行为观察结果表明,可在公园的不同空间提供不同设施,营造各式游戏场所氛围,服务于不同类型的儿童游戏活动。为了更加深入地理解空间布局与儿童对这些空间使用方式之间的关系,本研究继续从年龄差异的角度探究儿童空间使用情况的差异。

图11 儿童在后海公园里的空间分布密度Spatial density distribution of children in Houhai Park

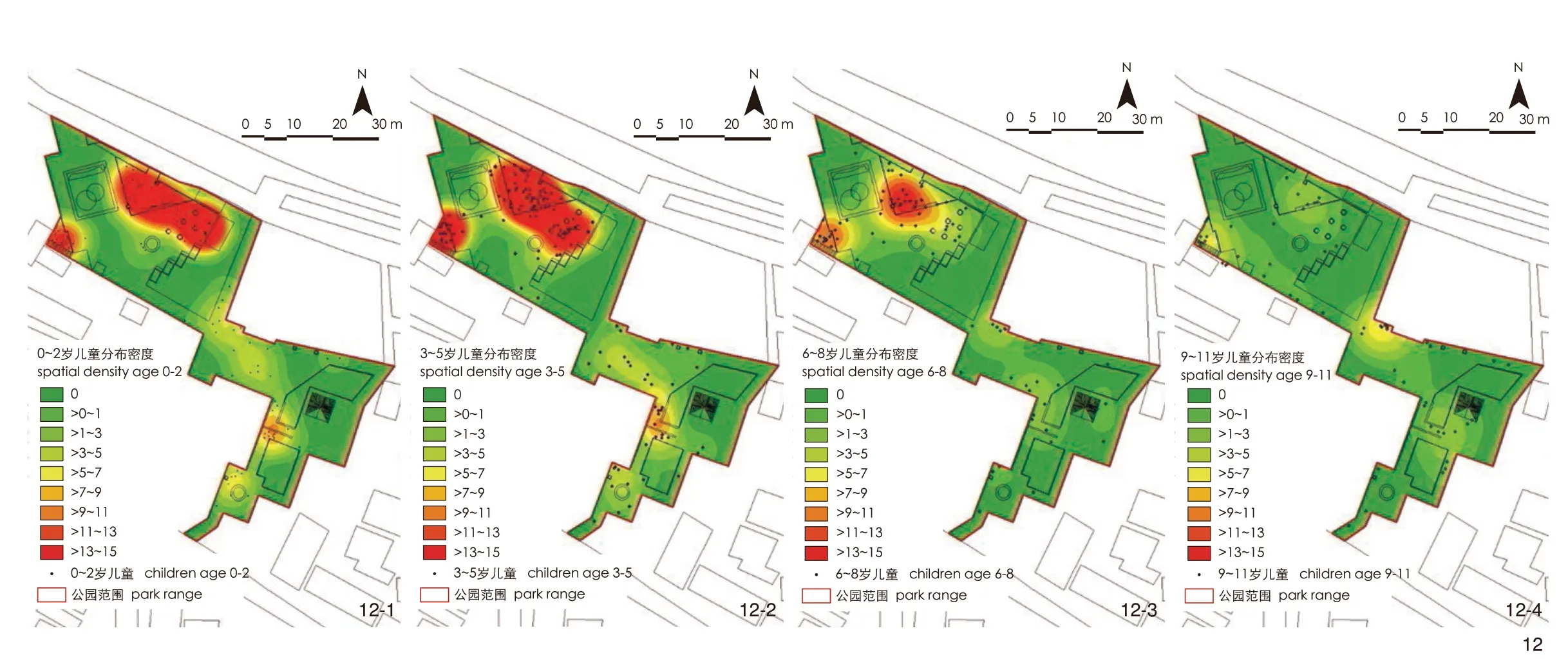

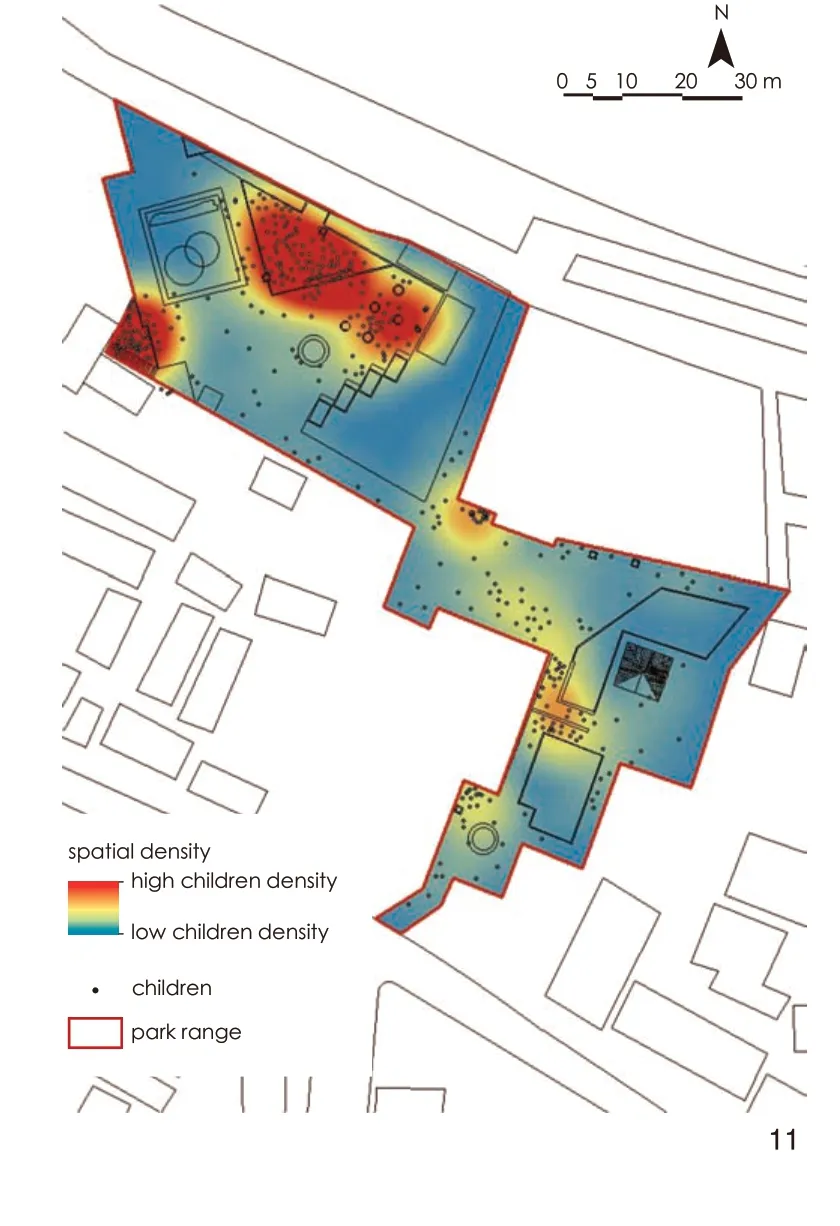

根据在后海公园进行儿童行为观察记录的年龄分布图(图12),年龄较小的儿童(<6岁)是在公园中进行户外活动的最主要儿童群体,集中在平坦的橡胶地垫游乐场、硬质铺装小广场和通往坡道的人行道区域。相反,相对年龄较大的儿童(6~9岁)群体较少光顾公园里的游乐场,而且对简单、固定的游乐设施兴趣低迷,他们愿意与同龄人在整个公园中进行追逐和奔跑等较高强度的体力活动。对于年龄更大一些的儿童(9~11岁),下棋或观棋是他们在公园中最经常进行的活动。因此,儿童对空间的选择和使用取决于活动内容,并受到场地可供性和年龄影响。年龄较小的儿童喜爱平坦的场地和固定的游戏设施;而年龄较大的儿童更需要能支持体力活动的场地,并在场地中发掘出更具挑战性的游戏方式,因此他们会更多利用发现空间来创造新的游戏体验。

图12 分龄儿童空间分布密度Spatial distribution density of children in different age groups

4 讨论

在高密度城区户外公共空间紧缺的背景下,儿童表现出了极强的适应性,他们利用日常生活环境中的各种空间和场地进行户外游戏活动,这样的现象和已有研究所探讨的情况相类似[3,29-31]。依据儿童进行户外活动的场地设置目的是否专为承载儿童户外活动[13],这些多样的场地可以分为专属空间、灵活空间以及发现空间3种类型。相较于存在安全隐患的发现空间,配备有固定游戏设备和平坦地面的专属空间由于其可供性和安全保护设计,更加适合儿童进行户外游戏。但是这些简单的游乐场由于仅能为低龄儿童提供有限的游戏机会,从一定程度上导致空间资源的浪费[12]。

高密度城市环境中的专属于儿童的游戏空间通常位于住宅区或公园里,配置的游戏设施常吸引儿童聚集。专属空间中常配置的设施大致可分为2种:一是为低龄儿童设计的固定游戏器材,如滑梯和秋千等;二是为成年人设计的户外健身器材,比如单杠和漫步机等。然而,儿童群体通常会将成年人户外健身器材当作鼓励儿童使用的游戏设施,虽然为大龄儿童提供了更具挑战性的游戏机会,但使用不当时也存在安全隐患。在城市公园中,橡胶地垫区域被低龄儿童视为理想游戏场地,简易设施因即时和简单的游戏机会能吸引较大年龄儿童停驻,但这样的可供性也让大龄儿童失去兴趣,从而寻找其他发现空间进行更有挑战性的户外活动[18,32-33]。

这也一定程度上解释了儿童经常使用日常环境中更灵活的空间(如广场和绿地)来进行游戏的原因。尽管这些空间缺乏专门设备,但各个年龄的儿童都会在这些灵活的空间里进行户外游戏。虽然这些空间设计的初衷不是活动场地,但其平坦而开敞的特性更加适合儿童进行中高强度的体力活动,包括跑步、跳跃、骑行和滑板骑行等[2]。

城市中心地区的发现空间是因儿童创造性地发现和利用了这些环境中的游戏机会而生成[14,34]。这也在本研究中得到了证实,后海公园里用于通行的坡道,特别受大龄儿童喜爱,是他们骑行和滑板的加速坡道;停车场和车行道等存在潜在安全隐患的空间,也承载了儿童日常户外游戏活动。然而,这些场地中的安全隐患会影响父母以及儿童选择户外活动空间,一定程度上阻碍了儿童进行更加多样的户外游戏。

总之,北京高密度城区缺乏户外公共空间,难以支持儿童多样化的户外活动[18,35]。不仅如此,设计形式单一的儿童专属游乐场也无法为多年龄阶段的儿童提供丰富的游戏机会,一定程度上造成了稀缺空间资源的浪费。而儿童自主开发使用的大量发现空间却因安全隐患,加重了家长对于儿童户外活动安全的担忧,从而限制儿童进行更加多样的户外游戏行为。

5 建议

为了让高密度城市环境更加儿童友好,本研究提出以下建议。1)儿童的游戏场不应设置边界,整个城市都可以成为他们的游乐场。因此,设计和开发各种游戏空间至关重要,综合考虑儿童专属的游乐场、灵活的开放空间、可供发现和使用的公共空间,以满足不同年龄段儿童的多样化需求和偏好,这也是实现儿童友好城市环境营造的重要内容。2)对于儿童专属的游戏场地设计应更具包容性,应考虑不同年龄阶段儿童的游戏偏好和场地需求。3)对于配有成人健身器材但被儿童认为是专属游乐场的地方,应该对健身器材进行有效的安全管控以降低潜在的危险,同时使儿童能够享受具有一定挑战性的游戏体验。4)对于可被更多年龄群体使用的灵活空间,关键在于创建满足整个社区需求的具有包容性的多功能区域,尤其是公园和公共广场应为游戏、运动、社交聚会等各种活动提供场地而设计,并且营造友好的社会氛围,鼓励不同年龄组共享,可以最大化公共空间服务潜力。5)对于发现空间,解决交通安全问题(包括改善行人通行条件、在游戏区周围设立安全区域、实施机动车交通管理)可以减小发现空间最主要面临的安全隐患。总之,城市公共户外空间应当更好地满足城市儿童多样化的户外活动需求,促进儿童进行体力活动,支持儿童认知发展,并为所有居民创造更安全、更健康的户外环境。

图片来源:

图1~4、11、12由作者绘制;图5~10由受访儿童拍摄。

(编辑 / 李清清)

作者简介:

(英)海伦·伍利 / 女 / 谢菲尔德大学风景园林系主任、教授 / 英国皇家风景园林协会成员 / GUIC国际研究组中国研究组组长 / 研究方向为城市公共绿色空间,重点关注儿童的户外空间

汤湃 / 女 / 博士 / 同济大学建筑与城市规划学院博士后 /GUIC国际研究组成员 / 研究方向为儿童友好型城市环境营造通信作者邮箱:20310251@tongji.edu.cn

WOOLLEY H, TANG P.Children’s Constructed and Found Play Spaces in High-Density Areas of Beijing: A Landscape - Sociology Perspective[J].Landscape Architecture, 2024, 31(2): 19-31.DOI: 10.3724/j.fjyl.202311210526.

Children’s Constructed and Found Play Spaces in High-Density Areas of Beijing: A Landscape - Sociology Perspective

(UK) Woolley Helen, TANG Pai*

Abstract:[Objective] Children have the innate ability to play almost anywhere.This study delves into how children creatively adapt to various urban outdoor play spaces in the high-density areas of Beijing.[Methods] Using the lens of landscape sociology, the research conducted a case study in the Shichahai area, employing data collection methods such as interviews, photo-voice, and behavior mappings to collect data about children’s daily use of outdoor environments.[Results] Based on the field research data, children's frequently used outdoor spaces can be classified into three types which are constructed,flexible and found spaces.Multiple lines of evidence point to the fact that constructed playgrounds with fixed equipment, though often criticized for constraining older children’s play opportunities, provide a structured and secure environment.However, safety concerns arise when children utilize adult exercise equipment inappropriately.These playgrounds are typically located in gated residential areas or central urban parks.Conversely, parks often feature rubber carpet playgrounds that younger children favor.Flexible spaces, such as squares and accessible green spaces, serve a wide age range due to their open design, accommodating highly physical activities like running, jumping,and cycling.Nevertheless, ensuring conflict-free access for children presents a challenge.Found spaces, while not originally intended for children, are frequently utilized despite potential safety risks, particularly in areas like car parking lots and vehicle access pavements.[Conclusion] Based on the research results, several recommendations are proposed.These suggestions aim to help urban areas cater to the diverse play needs of children, promote physical activity, support cognitive development, and create a safer and more engaging outdoor environment for all residents.

Keywords:high-density areas; child-friendly; affordance; found space; outdoor space

©BeijingLandscape ArchitectureJournal Periodical Office Co., Ltd.Published byLandscape ArchitectureJournal.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

1 Research Background

For many years, societies around the world have emphasized the importance of providing children with playgrounds for recreational activities.However, contrasting perspectives challenge this conventional belief.Notably, long-standing observers of children, such as Opie e.g.in 1969,have asserted that “Where children are is where they play”, while a sociological viewpoint posits that “play is the nature of childhood”[1-3].These assertions suggest an alternative perspective to the widely held societal belief that structured playgrounds are essential for supporting children’s play.progressed, various approaches were adopted.Lady Allen of Hurtwood (1897-1976), the first Fellow of the Landscape Institute in the UK, categorized different playground eras based on their characteristics and construction materials, including the concrete era and the maze period.These changes reflected the growing use of concrete as a new material post-World War II.In the latter half of the 20th century, playgrounds incorporated additional materials, such as brightly colored steel equipment and rubber surfaces, which replaced concrete and tarmac.While the need for fencing these spaces persisted, the fences became shorter and more colorful.Initially, fences were designed to keep dogs out but later evolved into structures aimed at containing children within the defined playground area, exemplifying what Woolley[12]referred to as the “Kit, Fence, Carpet” (KFC)approach to playgrounds — a meticulously constructed space.Other dedicated spaces designed for children include nursery playgrounds, school playgrounds, and skateboard parks.The KFC-style playgrounds of this kind still remain the mainstream approach in the design of children’s

1.1 The Origin of Constructed Play Spaces for Children

It is worth noting that in the past,playgrounds did not exist in many countries, and children roamed freely for recreation, a practice still prevalent in some parts of the world.This historical fact is exemplified in artworks likeOne Hundred Children at Playby Yang Jin, who was a court painter in the late 17th century andChildren’s Gamesby Pieter Bruegel the elder in 1560, which vividly capture the richness of children’s play.The latter part of the 19th century witnessed the emergence of playgrounds as a central space for children’s recreation in numerous regions across the globe.These developments were motivated by the belief that playgrounds could enhance children’s moral and physical development[2]and provide a safe haven from negative social influences[4].The advent of automobiles in the early 20th century introduced traffic concerns, dating back to the 1930s[5], a concern that persisted through the 20th century and into the 21st century[6-10].To address these concerns, some countries introduced legislation to facilitate the establishment of playgrounds.In England, theRecreation Grounds Act(1859) permitted the allocation of urban spaces for children’s play[11].These reflections on the adverse effects brought about by urban development issues on vulnerable groups in the city provide an opportunity for the development of playgrounds for children.

1.2 The Development of Constructed Play Spaces for Children

Initially, these spaces featured gymnasium equipment enclosed by high fences, but as time play areas, even though their capacity to accommodate a variety of children’s games is very limited.Especially for high-density cities worldwide today, low-capacity public spaces can be seen as a waste of valuable urban public space resources.Therefore, enhancing the service efficiency of urban public spaces, especially those dedicated to specific groups, through scientific methods is an effective way to achieve sustainable urban development.

1.3 The Introduction of Children’s Found Spaces

Considering the assertions that children play wherever they are and that play is inherent to childhood, it is clear that constructed spaces, of any kind, may not cater to the full spectrum of play that children engage in.Since the 1960s, various researchers, including Peter Opie and Iona Opie,Colin Ward, Roger Hart, and Robin Moore, have observed children engaging in play not only in designated areas but also in what we term “found spaces”[13].Common examples include steps in urban settings, which are typically used for sitting rather than their intended function of ascending and descending.Found spaces are areas originally designed for a different purpose but repurposed by children for play.Children have been observed using a wide range of found spaces, such as roads,paved areas, car parks, wildlife areas, planted areas,walls, fences, and flat garage roofs.None of these were designed with children’s play in mind, making them genuine “found spaces”.

1.4 Research on Children’s Found Spaces Based on the Theory of Affordance

Furthermore, the theory of affordance provides insight into why children use outdoor spaces not specifically designed for them as places for play.Gibson introduced the concept of affordance, suggesting that individuals can interact with their environment in ways they perceive as possible, beyond the environment’s original design[14].This perception is influenced by individual characteristics and how they match the elements of the environment.Affordances can be potential or actualized, depending on whether an individual recognizes the potential and acts on it[15].In subsequent developments, the affordance theory is not only used to explain how the environment influences children’s behaviour[16-18], but also employed to assess the supportive and inhibitory effects of the environment on children’s behaviour[19-21].Therefore, in this study, the affordance theory will also be used to explain children’s preferences for the use of various spatial environments in daily life.

Based on the above research background, this study focuses on how children growing up in highdensity urban areas in China utilize various types of spaces in their daily lives.Since the 1980s, China has undergone rapid urbanization, with a significant increase in urban population.The limited outdoor public spaces in cities have become increasingly inadequate to meet the diverse outdoor activity needs of residents of different age groups.Enhancing the service capacity of outdoor public spaces has become one of the methods to address this issue.Furthermore, the “14th Five-Year Plan”enacted in 2021 officially incorporates the goal of“building child-friendly cities” into the national development plan[22].In October of the same year, theGuiding Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Child-Friendly Citieswas issued, proposing the development goal of carrying out 100 pilot projects for the construction of child-friendly cities nationwide[23].Achieving these goals for childfriendly city construction not only involves creating more diverse playgrounds for children but also involves cultivating a more inclusive and friendly daily living environment for them.

However, despite these efforts, there is still limited knowledge about how children use various types of public spaces in their daily lives within the city.Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore, using the high-density urban areas of Beijing as an example, the usage patterns of various outdoor spaces by children in their daily lives, the behavioral motivations behind children’s use of different spatial environments, and to further discuss more efficient methods for creating childfriendly environments.The goal is to provide scientifically grounded recommendations for childfriendly environment creation tailored to the characteristics of urban environments in China.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research Design

Based on the research objectives, this study focuses on three main research questions: 1) What outdoor spaces, including exclusive and discovery spaces, do children use for daily play? 2) Why do children choose discovery spaces for play? 3) How can the overall environment be improved to enhance children’s outdoor play experience? To address these research questions, the study adopts a landscape sociology perspective in its research design.It primarily conducts data collection through sociological research methods and, based on diverse data sources, describes the phenomenon.On this basis, an explanation is provided for the causes of the phenomenon[24].The methodology is structured in a two-step process:firstly, conducting interviews with children to gain their perspectives on outdoor play experiences,with a particular focus on the places they frequently use for various outdoor activities.This approach enables a comprehensive understanding of children’s use of various locations within their surroundings, in the high-density urban areas.Subsequently, observations are conducted in the places most frequently mentioned by the majority of children to document various play activities and explore the affordance of each location.This twostep process not only provides insights into children’s play but also allows for an exploration of age-related differences in their use of found spaces.

2.2 Case study areas

This study conducts a case study in the distinctive yet representative Shichahai area in Beijing.Known for its historical and cultural significance, the region has implemented a strategy combining preservation and organic development.Due to the massive population influx brought about by urbanization, the resident population within the area has been steadily increasing.Under the combined influence of construction management and population influx, the Shichahai area has gradually developed spatial characteristics such as low-rise buildings, narrow streets, and high population density.In this situation, traditional buildings and limited outdoor spaces struggle to meet residents’ daily needs, posing a significant challenge for enhancing the overall living environment quality in the region.

During the pilot study, it was found that parks play a crucial role in providing more outdoor spaces for residents in the Shichahai area, serving as essential venues for daily activities in their lives.Within the Shichahai area, three parks stand out,with Beihai Park and Jingshan Park being iconic landmarks in Beijing.These parks attract millions of visiting tourists annually and, importantly,provide residents with valuable public green spaces to engage in outdoor activities in the densely populated inner-city environment.While the touristcrowded areas within these parks are attractions for visitors.In addition to these renowned tourist destinations, Houhai Park, although smaller in scale, offers residents a public green space for their daily outdoor activities.Differing from the bustling tourist areas, this park provides a quieter and more regular environment for residents to enjoy casual outdoor activities (Fig.1).

2.3 Data Collection

The primary data collection strategy involves a synthesis of interviews and observations,leveraging the strengths of both methods to enhance the accuracy of research results.This approach aids in gaining a more comprehensive understanding of complex social phenomena.

图1 The case study areas

In comparison to questionnaires, semistructured interviews conducted face-to-face with children provide a more effective means of following up on interesting responses and investigating underlying motives.Interviews prove invaluable in clarifying children’s comprehension and elucidating vague answers.To accommodate children’s varying comprehension levels and developmental characteristics, interviews are conducted in several specialized formats, including one-on-one interviews, focus groups, and the utilization of photo-voice, with the help from neighborhood committee.Photo-voice serves as the primary data collection method for understanding children’s use of their daily environment.This method, widely employed in behavioral and health research, is an effective way to document and communicate an individual’s unique experiences of different places[25-26].Following the guidelines proposed by Sutton-Brown[27], several steps are undertaken when employing photo-voice.Child participants,recruited from summer schools, are provided with digital cameras to capture photos of their daily play environments for three days.Subsequently, they meet with the researcher to discuss the photographs.In summary, a total of 131 children aged 6 to 12 participated in the interviews during the research (56 boys and 75 girls).Among these children, those with better expressive abilities,older age, and a willingness to participate in photo interviews were invited for the photo interviews.In the end, a total of 20 children aged 8 to 12 participated in the photo interviews, with each age group having 2 boys and 2 girls.

Observations can mitigate discrepancies between what individuals describe and what they actually do.Thus, observation proves to be a more effective method for recording activities in realworld settings[28].To document children’s diverse play activities, behavior mapping is systematically employed to assess children’s behavior within the physical characteristics of outdoor areas.Before commencing behavior mapping, Houhai Park is mapped through field measurements.The park is divided into two areas to facilitate immediate observations and record children’s activities.During on-site observations, boys and girls are distinguished with different symbols on the map,and their apparent age, along with a description of their activities, is recorded on a separate form.In each observation area, continuous observations were recorded for 5 minutes, with each child’s play activity being documented only once during that period.Behavioral observations took place between 5 pm and 7 pm each day, totaling 8 sessions throughout the study.The entire research spanned 8 days, covering 4 weekdays and 4 weekends.

图2 Word frequency analysis of spaces for play in close-to-home outdoor environment

图3 Word frequency analysis of spaces for play in further outdoor environment

图4 Constructed and found spaces in close-to-home outdoor environment

2.4 Data Analysis

The data analysis in this research unfolds in two distinct stages, providing a comprehensive understanding of children’s outdoor play experiences.1) Analysis of qualitative data collected from interviews: After transcribing and translating the audio recordings of interviews, semantic analysis of the interview content is conducted using Nvivo 12 software.Additionally, photos taken by children as part of the photo-voice method are linked to the respective interviews.These photos,along with the interpretational notes provided by the children, are integrated into the Nvivo platform, facilitating further refinement and organization during the data analysis process.These qualitative data, obtained through direct communication with the participants, collectively form the fundamental database for this research.2) Exploration of the availability of public open spaces through behavioral observation data:During the process of collecting behavioral observation data, each child and their behavior are marked on the map with different symbols.Through ArcGIS visualization analysis, the spatial patterns and relationships between children’s activities are explored.By structuring the data analysis into these two stages, the research not only captures the richness of children’s experiences but also offers a nuanced understanding of the physical environments in which these experiences occur.

3 Results

3.1 Children’s Use of Outdoor Public Spaces in Daily Lives

Based on the insights gathered through interviews, it becomes evident that children utilize a diverse range of outdoor spaces in their daily lives.A multitude of locations are frequently mentioned by the children, reflecting the breadth of their outdoor play experiences.Upon closer examination, a word frequency analysis highlights specific areas near their homes that children frequently use.These areas include courtyards,spaces near their homes, residential areas, and schoolyards (Fig.2).Children tend to frequent these spaces for their outdoor activities.Additionally, when children venture further from their homes, parks emerge as key destinations, with two specific parks, which are Houhai Park and Beihai Park, being particularly popular choices among the children (Fig.3).This analysis sheds light on the preferences and patterns of children’s outdoor play, revealing the significance of both immediate surroundings and accessible public spaces in their daily lives.

3.2 Constructed and Found Spaces in Close-to-Home Outdoor Environment

Children living in the densely populated innercity region of Beijing contend with limited outdoor spaces, leading them to seek various areas close to home for play.These spaces can be categorized as found spaces and constructed play spaces based on their original purposes (Fig.4).

3.2.1 Car Parking and Road as the Found Spaces

Among these diverse outdoor play spaces within children’s daily range, the most informal found spaces around their homes are often intended for car parking (Fig.5).Additionally,vehicle-accessible roads in residential areas are frequently mentioned as found places where children engage in play (Fig.6).Furthermore,pavements, free from vehicle traffic (Fig.7),expand children’s play experiences, fostering interaction with natural elements.These vehiclefree pavements, integral to their play routine,significantly contribute to outdoor activities.Children’s photos highlight not only the role of these pavements as play spaces but also their function as green areas in newly constructed residential neighborhoods.Notably, vehicle-free pavements extend beyond public green spaces; in hutong communities, they play a crucial role in providing daily outdoor play areas near children’s homes.

3.2.2 Square and Accessible Green Spaces as the Flexible Spaces

图5 Photos taken by children showing car parking as play spaces

图6 Photos taken by children showing vehicle accessible road as play spaces

图7 Photos taken by children showing pavements as play spaces

图8 Photos taken by children showing squares as play spaces

图9 Photos taken by children showing squares as play spaces

图10 Photos taken by children showing playground with physical exercise facilities and play facilities as play spaces

The squares within residential areas can be regarded as an extension of roads, offering open spaces for communal gatherings and shared activities.For children, these squares facilitate physical play, including activities such as scooter riding, ball games, chasing, and running (Fig.8).However, the shared nature of these spaces,accommodating various age groups with different preferences and needs, can sometimes lead to conflicts over the allocation of time and activity choices.While these squares provide children with ample space for outdoor physical activities, they must often compete with older community members for access to these resources.This lack of priority in using shared spaces puts children at a disadvantage in their attempts to utilize these squares for play, particularly when competing with adults and other age groups.

Furthermore, accessible green spaces within residential areas are another type of play space identified by children (Fig.9).These green areas offer urban children the valuable experience of interacting with natural elements, be it leaves, flowers,soil, or sand.Such natural play experiences are perceived as special and enjoyable by the children.

3.2.3 Playground as the Constructed Spaces

Formal constructed outdoor play spaces within the habitual range predominantly consist of playgrounds, which are equipped with physical exercise facilitiesor fixed play structures (Fig.10).These playgrounds serve to promote and facilitate various play behaviors.It’s worth noting that some playgrounds are equipped with sports and exercise facilities designed primarily for adults, but these spaces attract a considerable number of children.

The data gathered through photo-voice underscore the diverse nature of children’s daily use of spaces within their habitual range, ranging from informal play areas amidst car parking to formally designed children’s playgrounds.These varied play spaces offer distinct affordances,presenting children with various play opportunities and facilities.While some of these spaces are better suited for play, others exhibit limitations and potential safety risks.Despite these variations,these places remain the most accessible outdoor spaces for children residing in the central area of Beijing.

3.3 Constructed and Found Spaces in Parks

Based on the data collected through interviews, it is evident that Houhai Park offers several spaces highly favored by children (Fig.3).Among these preferred play areas, the most popular choices include the two rubber carpet playgrounds and the square adjacent to the large rubber carpet playground.The rubber carpet playgrounds provide children with ample flat ground for activities like chasing and running,while the tree-shaded square offers more secluded spaces conducive to stationary play.At the eastern corner of the square, kiddie rides are a hit among younger children.Additionally, the Chinese chess table appeals to some older children, while the slope bridging the level difference between different sections of the park is an excellent location for activities involving bicycles, scooters,and roller skates (Fig.11).These descriptions of space utilization within Houhai Park emphasize that different areas within the park offer varying atmospheres and are equipped with different facilities, providing distinct levels of affordance to support children’s play activities.To better comprehend the relationship between spatial arrangements and children’s use of these areas, it is essential to consider the spatial preferences of children across different age groups.

图11 Spatial distribution density of children in Houhai Park

图12 Spatial distribution density of children in different age groups

On the basis of the age distributions of children observed in Houhai Park (Fig.12), it reveals that younger children, those under six years old, make up the largest group.They tend to gravitate towards the flat rubber carpet playgrounds, the square adjacent to the large carpet playground, and the pavement leading to the slope.Conversely, older children, those over six years old,are less frequent visitors to the park and show reduced interest in the simple, fixed play facilities such as kiddie rides.Instead, they engage more with their peers in activities like chasing and running throughout the entire park, as indicated in Figures 8.For even older children, aged 9 to 11,playing chess emerges as their most frequently observed use of the park.Therefore, it can be seen that the choice of areas within Houhai Park largely depends on the specific activities children engage in, influenced by both the available facilities and the children’s age.Younger children tend to favor the flat carpet playgrounds and the fixed play facilities, while older children who seek more challenging, physically demanding activities find opportunities in informal play spaces to create new play experiences.

4 Discussion

Children exhibit remarkable adaptability,utilizing a wide array of spaces and places within their daily environment for play activities, in the high-density areas of Beijing, as evidenced by prior research[3,29-31].According to whether they have been designed especially for children[13], the places are described by identifying as them constructed,flexible or found play spaces.Comparing these different types of play space, the constructed playgrounds equipped with fixed play equipment and rubber carpet ground are more suitable for sustaining children’s play, providing protection and facilities for encouraging play, though these playgrounds are also criticized as only providing limited play opportunities[12].

For the constructed play spaces, in the high density urban central area, constructed playgrounds are usually located in gated residential area or parks.Within these playgrounds, the fixed play equipment are of two distinctive types: fixed play facilities for young children, such as slides and swings; and fixed exercise facilities for adults.Interestingly, in residential areas, children perceive the exercise facilities designed for adult physical exercise as play equipment, offering older children more challenging play opportunities.However,these facilities carry the potential risk of safety hazards when used inappropriately.In contrast,parks often feature rubber carpet playgrounds that are easily recognized by younger children as ideal play spaces, particularly those under six years old.Simple fixed play equipment, such as kiddie rides and chess tables, attract children by providing straightforward and immediate play opportunities.However, older children tend to lose interest in these basic play options, seeking more stimulating and challenging activities[18,32-33].

Beyond constructed playgrounds, children frequently use more flexible spaces within their daily environment, such as squares and accessible green spaces.Although these areas lack fixed equipment designed specifically for children,individuals of all age groups engage in play there.Children may not be the primary users of these spaces, yet their flat and open nature accommodates highly physical play activities, including running,jumping, cycling, and scooter riding[2].

Found spaces in central areas are not intended for children’s use, but children creatively discover and apply play opportunities within these environments[14,34].As evidenced by this research,these found places are frequently utilized by children.For example, slopes bridging different levels in places like Houhai Park are especially favored by older children, serving as speed-up slopes for bicycle riding and scooter play.Despite potential safety risks, particularly in areas like car parking spaces and vehicle access pavements, as reported during photo-voice sessions, children find ways to utilize these available spaces in their surroundings.The risk of traffic-related dangers can impact parents’ and children’s perceptions,potentially hindering outdoor play.

To conclude, for children residing in densely populated central areas of Beijing, the available play spaces in their daily environment often fall short in providing diverse affordance[18,35]to promote and sustain play.Constructed playgrounds may not offer adequate opportunities for older children.Flexible spaces, shared across age groups, may not actively encourage children’s play and can limit their utilization.The potential safety risks associated with found spaces can amplify parental concerns, potentially curbing children’s outdoor play.

5 Suggestion

To create a more child-friendly urban environment, we propose several recommendations based on the research findings.Firstly, children’s play knows no bounds, and the entire urban environment can serve as their playground.Hence,it is imperative to design and develop a variety of play spaces within urban settings, encompassing constructed playgrounds, flexible open spaces, and found areas, to cater to the diverse needs and preferences of children across various age groups.For constructed spaces, formal playground designs should be more inclusive, considering children of different age groups.Additionally, implementing effective safety measures in constructed playgrounds, especially those equipped with equipment intended for adults, can help mitigate potential hazards while still enabling older children to enjoy challenging play experiences.Regarding flexible spaces, the goal is to create multifunctional areas that meet the needs of the entire community.Parks and public squares should be designed to accommodate a range of activities,including play, sports, social gatherings, and more.Encouraging shared usage of public spaces among different age groups can maximize the potential of these flexible areas.This approach ensures that children can partake in play activities without conflicts with other users.As for found spaces,addressing traffic safety concerns involves improving pedestrian access, establishing secure zones around play areas, and implementing trafficcalming measures to minimize risks associated with found spaces near roads and vehicle access points.In summary, by implementing these recommendations, urban areas can better accommodate the diverse play needs of children,promote physical activity, support cognitive development, and contribute to a safer, more engaging outdoor environment for all residents.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.1-4, 11, 12 were down by authors; Fig.5-10 were captured by participating children during the interview.

(Editor / LI Qingqing)

Authors:

Helen Woolley (UK) is director of and professor in the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Sheffield, and a fellow of the Landscape Institute and the Royal Society of Arts, and team leader of the GUIC(Growing Up in City) International Program in China.Her research focuses on green and open spaces with an emphasis on children’s outdoor environments.

TANG Pai, Ph.D., is a postdoctoral researcher in the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, and a member of the GUIC (Growing Up in City)International Program.Her research focuses on childfriendly urban planning and design.

Corresponding author Email: 20310251@tongji.edu.cn