第三方惩罚行为的认知神经机制

郑好 陈荣荣 买晓琴

摘 要 第三方惩罚(third-party punishment, TPP)指个体作为第三方或者观察者为维护社会规范对违规者所实施的惩罚行为。大量研究为揭示TPP行为的神经机制提供了启示, 但鲜有研究关注不同功能性脑网络在其中发挥的整体作用。本文综述了近10年来TPP相关的研究, 对相关理论模型和脑网络进行总结, 并在此基础上提出TPP的认知神经网络模型, 系统地对TPP行为背后的神经机制进行解释和整合。在该模型中, 情绪系统和奖赏系统是TPP的动力来源, 认知系统主要负责责任评估以及惩罚的选择; 奖赏网络、突显网络、默认模式网络和中央执行网络分别参与不同认知加工阶段。该模型建立了TPP相关研究在心理层面和认知神经层面上的联系, 对TPP行为的发生和发展机制进行了更加整体、全面的解释。未来可以引入元分析或基于机器学习的分析方法, 在不同的背景信息和更加复杂的社交情境下探讨第三方干预偏好以及背后的认知神经机制。

关键词 第三方惩罚, 认知神经机制, 脑网络, fMRI

分类号 B845; B849: C91

1 前言

社会规范的建立与执行是人类区别于其他动物的显著特征之一(K?ster et al., 2022), 但日常生活中违规行为仍然普遍存在。增加制度约束可以提高人们遵守规范的可能性(Fehr & Schurtenberger, 2018)。社会惩罚是一种常见的道德和制度约束行为(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004b), 分为第二方惩罚和第三方惩罚(third-party punishment, TPP)。不同于“以恶制恶、以牙还牙”的第二方惩罚行为, TPP指个体作为第三方或者观察者为维护社会规范对违规者所实施的惩罚行为(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004a; Kanakogi et al., 2022)。一般而言, 这种惩罚不会给个体带来直接利益, 且需要付出一定代价, 因此常被看作一种利他惩罚(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003)。TPP约束和规范了人类行为, 进一步维系并促进了社会公平和社会合作, 因而受到研究者们广泛的关注(Fehr & G?chter, 2002; Kim et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022)。

上个世纪以来, 人们针对经济决策与分配行为开展了大量研究。行为经济学家最早在最后通牒博弈任务(Ultimatum Game, UG)中发现了利他惩罚(Thaler, 1988)。在该任务中存在提议者和响应者两方, 他们需要就一定数量的资金如何分配达成一致。首先由提议者提出分配方案, 若响应者接受提议者提出的分配方案, 则两人按照这一方式进行分配, 反之, 两人都不能获得任何资金。在这种情况下, 拒绝可以看作是响应者对提议者的有代价的第二方惩罚。然而, 在现实世界中, 第二方往往是被动接受的角色。并且, 如果仅存在第二方惩罚, 能够维护的社会规范数量有限, 因此, 引入第三方惩罚能够扩大惩罚违规者的比例, 更好地维护社会规范。以Fehr为代表的学者在实验室条件下证明了第三方惩罚的存在。Fehr和Fischbacher (2004a)在独裁者博弈任务(Dictator Game, DG)中引入第三方, DG与UG的区别在于响应者不能拒绝独裁者(提议者)提出的分配方法, 只能被动地接受, 作为第三方观察者的被试在看到独裁者的分配方案后, 可以通过付出一定代价(减少自己的钱数)来惩罚独裁者。随后, 该范式成为TPP的重要研究方法之一, 为在实验室条件下研究社会规范行为提供了一种新的思路。研究者在该范式基础上操纵独裁者和响应者的社会地位(Cui et al., 2019; Ouyang et al., 2021)、分配不公平的程度(Sun et al., 2015)、惩罚代价的高低(Cheng et al., 2022)以及第三方个体与任务双方之间的社会距离和群体关系(Bernhard et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2018)等变量来进一步探究TPP行为是否受到社交情境或背景信息的影响。除了DG, 常用在TPP研究中的范式还包括公共物品博弈(Zhou et al., 2017; 唐捷 等, 2022)、信任博弈(Konishi & Ohtsubo, 2015)、囚徒困境(Lergetporer et al., 2014)、正义游戏(Civai et al., 2019)和芝加哥道德敏感任务(Kim et al., 2021; Meidenbauer et al., 2018)等, 通常研究者关注第三方是否会对违规行为作出干预以及哪些因素会影响这种干预行为。

随着研究的深入, 研究者开始从电生理和功能成像层面的证据推测TPP行为背后的认知神经机制。但是由于研究方法的局限性, 这些证据大多局限于某单一成分或者仅仅关注独立脑区激活的结果。并且, 目前尚未形成对TPP行为背后认知过程与脑功能网络之间联系的整体认识。因此, 本文对近10年来与TPP相关的研究进行梳理。首先进行文献检索。英文文献检索使用Web of Science、PubMed、ScienceDirect数据库, TPP的关键词為“third-party punishment”或“altruistic punishment”或“social punishment”, 认知神经机制的关键词为“cognitive”或“neural bias”或“neural correlates”或“neuroimaging”或“fMRI”。中文文献检索使用知网、万方、维普数据库, TPP的关键词为“第三方惩罚”或“利他惩罚”或“社会惩罚”, 认知神经机制的关键词为“认知”或“神经机制”或“神经基础”或“脑成像”。同时, 在阅读文后参考文献时利用滚雪球的方法检索文献进行查漏补缺。截止2023年4月, 共检索到文献1149篇, 文献检索的时间范围为2013年4月到2023年4月。经初筛、审查等阶段后, 最终纳入文献数量为60, 其中涉及神经机制的文献39篇。文献纳入与排除标准及PRISMA流程图见网络版附录图S1。在总结前人研究的基础上, 本文首先介绍TPP行为相关的理论模型, 从理论层面对TPP行为进行解读; 其次, 总结参与TPP行为的脑网络相关证据, 尤其关注脑区之间的协同作用; 最后, 基于已有的理论和研究构建TPP的认知神经网络模型, 为理解TPP行为提供一个新的动态视角。

2 第三方惩罚相关理论模型

TPP作为一种复杂的利他行为, 揭示背后的认知机制能够更好地理解其发生和发展规律。前人研究发现情绪、认知控制以及情境等因素会对TPP行为产生影响。然而, 目前对TPP理论层面的认识仍有不足, 大多数研究结果的解释以社会价值决策相关的理论模型为基础。因此, 我们首先对能够解释TPP行为的理论进行总结, 以形成对TPP行为理论层面的理解。这些理论模型包括反映个体合作与公平偏好的互惠模型、直觉式加工的情绪模型以及在强化学习视角下, 将情绪和认知因素融合起来的双系统模型。

2.1 互惠模型

“你帮助我, 我帮助你”, 互惠指以一种类似的方式回报他人的行为, 对促进人类合作具有重要意义(Guala, 2012)。TPP行为的产生包含两种互惠原则:弱互惠和强互惠(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2003)。在TPP中, 弱互惠一般指间接互惠, 个体将TPP这一高成本利他行为作为一个“可信”的信號来向他人暗示自己拥有公平公正的高尚品质, 藉此在群体中建立声誉, 以便于在今后的人际交往中获得更多的机会和合作, 进而实现间接获益(Jordan, Hoffman, et al., 2016; Rai, 2022)。与期望获益的弱互惠不同, 强互惠认为个体是出于维护公平的动机来惩罚不公平的行为(Ciaramidaro et al., 2018), 即使实施惩罚需要付出代价, 且这些代价不一定能够得到补偿。强互惠者的存在保证了群体利益, 也使得人和人之间的广泛合作成为可能, 符合进化原则(Buckholtz & Marois, 2012)。

互惠模型从宏观的视角解释了TPP的发生机制, 指出个体是在基于合作与公平的情况下做出的惩罚行为。然而, 该模型也有不足之处。首先, 间接互惠强调个体第三方惩罚的目的是获取间接利益。在单试次或者匿名情况下, 由于个体几乎不存在未来的合作机会, 或者无法辨识身份, 因此并不存在声誉动机。以往研究揭示即使在这种情况下, 个体依旧会执行TPP, 并且发生概率高于1/2。例如, Piazza和Bering (2008)发现在第三方完全匿名的条件下, 71.4%的参与者选择牺牲1/3的资金去惩罚违规者; Feng等人(2022)也发现在单次匿名实验中个体的平均惩罚率大于50%。国内研究者杨莎莎和陈思静(2022)同样发现在单次匿名博弈中不惩罚或低惩罚的情况并不常见(3.15%)。此外, 最近的研究发现即使是未涉足社会的仅8个月大的婴儿就已经能够使用目光来惩罚违规者(Kanakogi et al., 2022)。以上研究发现都无法用间接互惠来解释。其次, 强互惠没有考虑到惩罚所带来的报复性行为, 这并不利于群体的发展和稳定。最后, 强互惠惩罚是一种自愿的惩罚行为, 其强度对惩罚成本十分敏感。若惩罚成本过高, 第三方作为利益无关者在理性的考虑下对需要自己承担成本来实施惩罚的需求便会降低。可见, 仅从公平、合作的互惠角度来理解TPP行为存在一定的局限性。

2.2 情绪模型

“情感即信息”模型(affect-as-information)指出, 情感是一种简化判断的启发式工具, 可以作为决策过程中的信息来源指导决策(Bright & Goodman- Delahunty, 2006), 进而影响个体的后续决策(Zhao et al., 2022)。负性情绪产生是TPP的动机来源之一(Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004a; Fehr & G?chter, 2002; Xiao & Houser, 2005)。个体观察到违规行为发生时会产生一系列的负性情绪, 包括对违规者的愤怒(Jordan, McAuliffe, & Rand, 2016)以及对自私意图(McAuliffe et al., 2015)和不公平(Raihani & McAuliffe, 2012; Sun et al., 2015)的厌恶。此时个体的初衷可能是想通过惩罚违规者的方式来缓解自己的负性情绪, 而维护社会规范只是一种“额外获益” (de Quervain et al., 2004)。

但也有研究学者发现, 负性情绪并不一定导致惩罚行为。例如, Qu等人(2014)采用第三方惩罚的DG任务发现, 在负性情绪与惩罚成本导致的经济损失冲突之下, 个体选择“不惩罚”的情况也会发生。另外, 在个体情绪激活相同的情况下, 惩罚程度仍然存在差异。研究发现, 即使个体对分配不公平程度的感知相同, 即不公平厌恶程度相同, 最终的惩罚程度还是会因惩罚成本的不同而发生改变(Cheng et al., 2022)。以上研究表明, 情绪可能影响了反应判断的某个阶段, 最终的惩罚决策是结合各方面因素综合考量的结果, 包括情绪、公平和自利的权衡。

2.3 强化学习视角下的双系统模型

强化学习(reinforcement learning, RL)指个体通过接收环境的反馈信息进行学习并不断调整行为策略, 是一种奖励学习的方法(K?ster et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2017)。双系统理论认为, 社会决策受到自动加工和控制加工两个系统的影响(Chung et al., 2023)。前者属于自下而上的启发式加工过程, 负性情绪的产生促使惩罚成为自动化优势反应(Mussel et al., 2018), 对应着RL中无模型(model-free, MF)的策略; 后者属于自上而下的加工, 个体会在理性、经验的引导下选择最优的行为方式(Zhou et al., 2014), 对应着RL中基于模型(model-based, MB)的策略。以往研究表明, 个体的最终决策属于双系统之间的动态平衡(张慧 等, 2018)。其中, MF以直觉冲动的方式(最少成本)进行决策, 同时又会受到MB的影响和控制, 体现了个体在不同系统的互动中探索适应性的行为(Gershman et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014)。

在TPP中, 当违规行为发生时, 个体的自动化情感评价激活了惩罚行为, 体现了情绪对惩罚的驱动(Qu et al., 2014); 当直觉反应和经济利益产生冲突时, MB对MF进行认知控制, 最终的惩罚决定是个体“深思熟虑”后的结果(殷西乐 等, 2019)。惩罚行为发生后, 其带来的满足感和权力的体验感(Delgado et al., 2003; Strobel et al., 2011; Yamagishi et al., 2017)帮助个体建立了较高的自尊水平, 并联合负性情绪的消解以及对未来回报的期待共同作为奖励信号进行内部强化, 促使个体做出下一次惩罚行为。

该模型将传统的双系统理论以强化学习的视角展现出来, 从一个全新的角度探讨了TPP行为的发生和发展过程。具体来说, 该模型不仅将情绪和认知因素结合起来, 还指出TPP应是一个有反馈和强化参与的动态过程, 个体会在每一次的反馈中进行学习, 最终形成稳定的行为模式。然而, 该模型并未涉及个体对违规行为原因的推测。有研究指出, 对非故意违规者的意图评估可能会抑制杏仁核的活动, 减少因情绪冲动产生的惩罚(Treadway et al., 2014)。这启示我们未来在利用该模型对TPP行为的产生机制进行解释时, 还应考虑对违规者心理状态的评估这一重要因素。

以上理论模型从不同的角度阐述了TPP行为产生的机制。然而, 现有理论模型对TPP行为的解释存在一定的局限性。越来越多的研究者将TPP看作一个有反馈参与的动态性过程。所谓动态性, 指需要满足多系统性和时间性两个特征(Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006)。TPP作为一种复杂的社会行为, 其产生可能是个体情绪、认知和奖赏等多个系统交互作用的结果, 符合多系统性; 另外, 奖赏反馈的存在使得个体可以在每一次强化中对TPP行为进行调整, 事件相关电位(event-related potential, ERP)研究也发现在不同的阶段会有不同的脑电成分出现, 如分别在刺激后200~350 ms和300~ 900 ms左右達到峰值的内侧额叶负波(medial frontal negativity, MFN)和晚期正成分(late positive component, LPC), 其波幅大小与后续的惩罚程度相关(Cui et al., 2019; Qu et al., 2014), 符合时间性的特征。

早在2011年, Strobel等人就提出了在强互惠行为背后, 认知?情感?动机网络作为利他惩罚驱动力的观点, 但由于在实验中缺乏情绪评分, 无法直接得出到底是哪种情绪影响了TPP行为的结论; 随后, Buckholtz和Marois (2012)指出TPP的成功执行需要责任评估和惩罚选择两个独立认知机制的支撑, 一定程度上将认知与行为决策结合起来, 但没有纳入情绪因素的影响。目前, 许多研究致力于证明情感和认知塑造了人类的亲社会行为, 但对决策的具体过程以及情绪和认知相互作用的机制仍不了解(Rahal & Fiedler, 2022), 且相关研究证据分布零散, 缺乏整体认识。借助神经层面上的证据有助于对决策者做出决定时的复杂认知和情感过程进行更细致的理解。因此, 我们回顾与TPP相关的功能神经成像和电生理相关的证据, 尤其关注脑网络内部和脑网络之间的联系, 为理解TPP行为奠定神经层面的基础。

3 参与第三方惩罚的脑网络

以往研究表明TPP包含情绪产生、意图和伤害程度评估以及选择惩罚阶段。结合前人研究中相关脑网络的功能与激活模式(Bellucci et al., 2020; Krueger & Hoffman, 2016; Lo Gerfo et al., 2019), 本文认为TPP行为的产生分为“情绪产生”、“责任评估”和“惩罚选择”三个阶段, 与之相对应的脑网络为突显网络(salient network)、默认模式网络(default mode network)和中央执行网络(central executive network)。此外, 奖赏网络协作TPP加工过程, 主要起价值表征、预期奖赏的作用。相关脑网络所包含的脑区及其位置见图1。

3.1 突显网络

公平是一种默认的社会规范(Civai, 2013), 当违规行为发生时, 个体会产生愤怒、不公平厌恶等负性情绪, 这种愤怒和厌恶属于以他人为中心的道德情绪(Pedersen et al., 2018)。此外, 当个体预期自己应当惩罚违规者以维护正义却没有这样做时, 会产生以自我为中心的内疚感(Nelissen & Zeelenberg, 2009), 这种内疚感在一定程度上促进愤怒情绪的产生(Rothschild & Keefer, 2018)。因此, 突显网络负责检测冲突并产生愤怒、厌恶、内疚等负性情绪(Bellucci et al., 2020; Buckholtz & Marois, 2012; Feng et al., 2016; Mclatchie et al., 2016), 主要脑区包括背侧前扣带皮层(dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dACC)、前脑岛皮层(anterior insula cortex, AIC)和杏仁核。

前人研究指出, dACC在监测认知冲突中发挥着重要作用(Wang et al., 2017), AIC与负性情绪表征相关(Shenhav et al., 2016; Singer et al., 2009)。Craig (2009)将这两者整合到脑岛功能模型中, 认为它们共同参与情绪加工。当个体观察到不公平行为时, dACC和AIC负责监测违反规范的情况或威胁(Feng et al., 2016), 并由AIC标记违规信号和产生不公平厌恶反应(Civai et al., 2012; Hu, Blue et al., 2016)。研究发现AIC激活程度与分配不公平程度呈正相关(Zhong et al., 2016)。相关ERP研究也发现在该过程中源定位在前扣带皮层(anterior cingulate cortex, ACC)附近的MFN波幅增大, 该成分对社会期望和社会规范的违反敏感(Mothes et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2015; van der Helden et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011)。这些研究结果体现了dACC和AIC可能对应结果的早期评价加工过程。另外, 杏仁核作为社会与情感的重要脑区之一, 在TPP中负责根据受害者的受伤害程度产生情感唤醒信号(Buckholtz & Marois, 2012; Krueger & Hoffman, 2016), 并参与决定了惩罚的严重程度(Stallen et al., 2018)。简单来说, AIC和杏仁核体现了对不公平行为反应决策的两个不同方面, 前者反映了个体的社会偏好与惩罚意愿; 后者反映了个体的情感体验并且影响惩罚程度(Civai et al., 2019)。综上, 突显网络在TPP中负责对违规行为进行检测, 参与情绪加工并指导后续决策, 为情绪模型提供了证据支持。然而, 有研究者指出, 以AIC为核心的突显网络启动并调节了大脑其他区域参与的认知?情感?动机过程(Menon & Uddin, 2010)。因此我们推测, 突显网络在TPP过程中起到重要作用。

3.2 默认模式网络

个体在做出惩罚决策之前, 需要对违规行为的伤害程度和伤害意图进行评估, 并将其整合到责任的评估, 从而形成“惩罚信号”。该过程所涉及的网络称为默认模式网络, 主要包括内侧前额叶皮层(medial prefrontal cortex, mPFC)和颞顶联合区(temporoparietal junction, TPJ)。其中, 腹内侧前额叶皮层(ventromedial prefrontal cortex, vmPFC)负责对受伤害的程度进行评估(Bellucci et al., 2017), 与杏仁核的功能连接增强表明这两个区域可能共同负责伤害程度的情感编码(Treadway et al., 2014)。背內侧前额叶皮层(dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, dmPFC)和TPJ与推断他人心理状态有关(Jamali et al., 2021; Morese et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2020; Yang, Shao, et al., 2019)。dmPFC与TPJ在TPP中负责对伤害者的意图进行评估, 并且其激活程度及两者的功能连接强度与惩罚程度呈负相关(Baumgartner et al., 2012, 2014; Moll et al., 2018; Zinchenko et al., 2019)。这可能是个体对违规行为进行了合理的推测与解释。当伤害是无意发生时, TPJ-mPFC环路会抑制杏仁核的活动, 使得惩罚程度降低(Treadway et al., 2014)。这体现了对违规者心理状态评估在TPP行为实施过程中起到的重要作用。

前人研究发现, 在与TPP相关的大脑区域之间存在一种独特的连接方式, dmPFC是TPP激活模式的中枢(Bellucci et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2016)。中枢(hub)是指在格兰杰因果分析(Granger causality analysis)中与其他节点有最大数量因果联系的大脑区域, 是信息交流的中心节点(Yang et al., 2023), 在这里体现为dmPFC与其他脑区之间有更多数量的功能连接。结合不同脑区的功能, 我们对默认模式网络作用方式做出如下推测(图2):颞极(temporal pole, TP)负责理解违规行为, 并向dmPFC提供伤害信息。dmPFC在接收到伤害信息之后对伤害意图进行评估, 并向其他区域传递信息, 包括后扣带皮层(posterior cingulate cortex, PCC)、vmPFC和TPJ。其中, PCC负责整合与违规行为相关的背景信息, vmPFC负责编码伤害程度, TPJ负责推断意图, 最后由mPFC整合伤害与意图两部分信息, 形成“惩罚信号” (谢东杰, 苏彦捷, 2019)。

值得注意的是, dmPFC和TPJ都有着推断意图的作用, 是认知心智化的关键脑区(Feng et al., 2022)。此外, vmPFC和杏仁核与情感心智化相关(Anne et al., 2012), 有人提出这4个脑区共同组成心智化网络(mentalizing network) (Feng et al., 2016; Glass et al., 2016)。心智化网络能够推断他人心理状态, 减弱对违规行为的监测, 降低社会规范的价值计算水平。实际上, Bellucci等人(2017)认为默认模式网络和心智化网络在本质上属于同一网络, 而另一些研究者则认为默认模式网络和心智化网络在TPP中应各司其职, 共同影响TPP行为(Lo Gerfo et al., 2019)。两者虽在关系上存在不一致的说法, 但不可否认的是二者不管是在结构上还是功能上都存在相似性, 默认模式网络更加侧重于对违规行为整体的责任评估, 而心智化网络强调对他人心理状态的推断。换言之, 默认模式网络可能是通过心智化网络起到责任评估的作用, 两者间是相辅相成、共同作用的。

3.3 中央执行网络

Buckholtz等人(2015)认为, 责任评估和惩罚选择属于两个独立的认知机制, 后者所对应的脑网络是中央执行网络。中央执行网络在TPP中负责将默认模式网络发出的“惩罚信号”转变为“惩罚行为” (Lo Gerfo et al., 2019; Zinchenko & Klucharev, 2017)。相关脑区包括背外侧前额叶皮层(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, dlPFC)、后顶叶皮层(posterior parietal cortex, PPC)和顶叶内沟(intraparietal sulcus, IPS)。

当中央执行网络接收到默认模式网络传来的“惩罚信号”时, IPS负责将场景与惩罚行为联系起来, PPC负责构建惩罚类型等级表, 最后由dlPFC在等级表中选择特定惩罚, 代表最终输出(Buckholtz et al., 2008; Glass et al., 2016; Krueger & Hoffman, 2016)。大量研究指出dlPFC在认知控制即抑制负性情绪和自利倾向中起着重要作用(Knoch et al., 2006, 2008; Sanfey et al., 2003; 罗艺 等, 2013), 该结论在TPP中也得到了验证(Feng et al., 2016; 殷西乐 等, 2019)。相关ERP研究发现, 晚期成分LPC波幅与认知努力程度相关(Cui et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2008), 表明最终的惩罚决策是负性情绪和自利机制权衡的结果。此外, dlPFC还与目标导向行为的整合与选择相关(罗艺 等, 2013), 若利用重复经颅磁刺激(repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation, rTMS)抑制dlPFC活动会干扰最终的惩罚决定(Buckholtz et al., 2015)。由上我们推测, dlPFC作为中央执行网络的核心脑区, 其激活体现了认知控制在反应判断后期所起到的重要作用, 也为双系统模型下控制系统的存在提供了神经层面上的证据支持。

此外, 在中央执行网络中还存在另一个重要脑区——腹外侧前额叶皮层(ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, vlPFC)。Glass等人(2016)指出vlPFC虽然对TPP的顺利实施很重要, 但却与其没有内在联系, 然而Bellucci等人(2020)的一项元分析发现TPP会持续激活vlPFC。令人遗憾的是, 目前没有研究直接关注vlPFC与TPP行为的关系。前人研究已证实vlPFC是亲社会行为调控中的一个关键脑区(Yang, Zheng, et al., 2019), 因此我们推测vlPFC可能在抑制以伤害为目的的惩罚冲动、促进更加公平的制裁中发挥重要作用。未来的研究需要进一步将vlPFC作为目标区域来探究其在TPP中的功能。

3.4 奖赏网络

TPP行为的产生涉及奖赏加工, 特别是内部奖赏。根据RL理论, 个体对违规者进行惩罚而获得满足感和权力体验感会作为内部奖赏促使个体做出下一次惩罚行为, 这也是TPP行为得以进化的近端机制(张耀华 等, 2013)。Brüne等人(2021)发现亨廷顿病患者能够理解不公平行为本身, 却可能因为缺乏奖赏体验能力而导致TPP行为减少, 体现了奖赏加工在TPP中发挥的重要作用。在神经层面上, 不少研究发现TPP会激活奖赏加工相关的脑区, 主要包括腹侧纹状体(ventral striatum, VS)和vmPFC (Hu et al., 2015), 两者与中脑腹侧被盖区(ventral tegmental area, VTA)相连, 分别构成中脑边缘通路和中脑皮质通路(Ikemoto, 2010)。中脑边缘通路中的VS在预期未来奖赏中发挥重要作用(ODoherty et al., 2004), 在TPP中其激活程度及其与vmPFC的功能连接增强(Hu et al., 2015)。中脑皮质通路中的vmPFC是情感和认知处理的关键脑区(Naqvi et al., 2006; 刘映杰 等, 2022)。前文所提到的vmPFC对伤害程度的评估体现了其将情绪整合到TPP中的功能(Asp et al., 2019)。在认知加工上, vmPFC负责决策中的主观价值评估(Ruff & Fehr, 2014), 其激活会正向强化社会奖赏(Zhong et al., 2016)。以上证据说明, 奖赏网络在TPP中主要负责价值表征、预期奖赏的作用。

此外, VTA富含神经递质多巴胺, 其在中脑边缘通路和中脑皮质通路神经传导过程中起到重要作用(Wise & Rompre, 1989)。具体来说, 多巴胺负责编码奖赏预测偏差(Schultz, 2007, 2013)。当大脑监测到结果比预期更差时, 由ACC和多巴胺系统对该信号进行编码, 这可能是在脑电研究中发现MFN在违反预期条件下出现的原因(Enge et al., 2017; 吴燕, 罗跃嘉, 2011), 这可以解释在个体观察到不公平分配后MFN波幅增大的现象(Ouyang et al., 2021)。大量研究发现, dlPFC和dACC等脑区在TPP中的活动会受到来自中脑多巴胺能神經元信号输入的调节(Lockwood et al., 2016)。多巴胺功能分子的遗传变异可用于解释个体间在TPP中神经激活的差异。COMT Met等位基因与体验奖赏的能力有关, 该基因携带者在TPP中VS有更强的激活(Strobel et al., 2011)。由此可以说明, 多巴胺水平在TPP决策中有着重要影响, 且该过程与奖赏加工密切相关。

4 第三方惩罚的认知神经网络模型

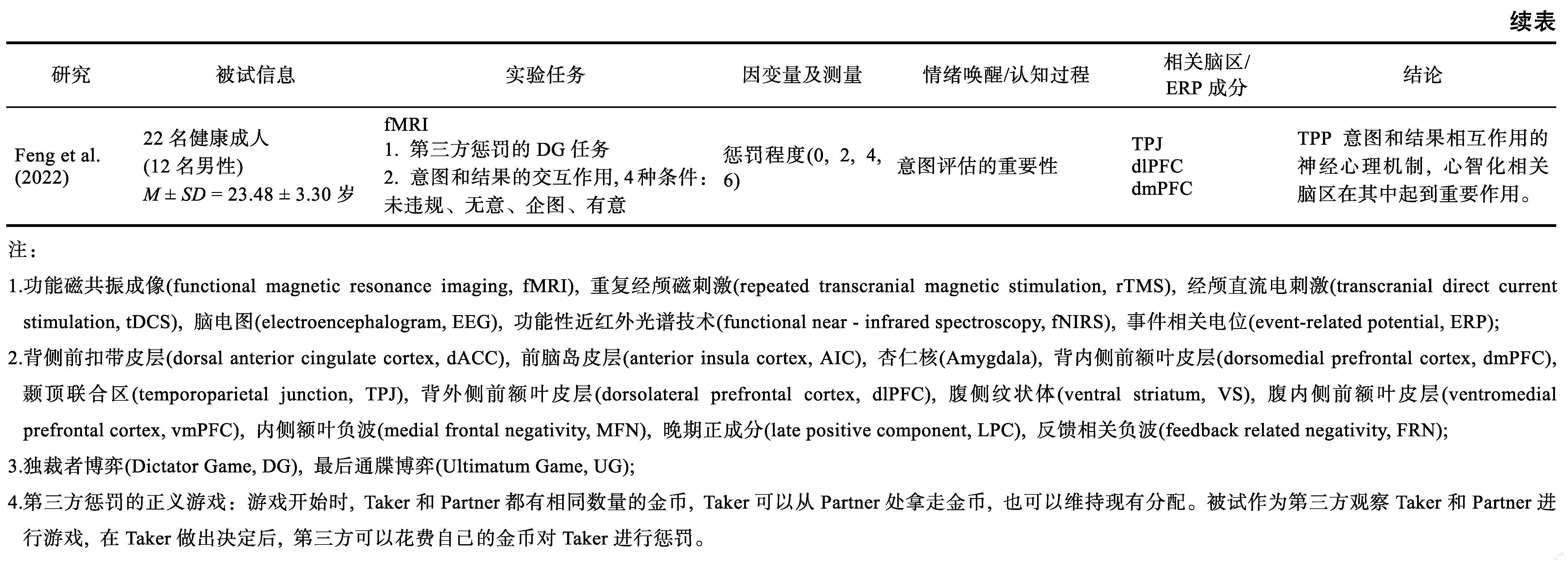

前人在TPP相关神经机制上开展了大量研究, 但大多仅仅关注了TPP行为出现时大脑各部位的独立激活。近年来有学者对TPP持续激活的神经网络进行了元分析(Bellucci et al., 2020), 但依旧对大脑区域和网络之间的相互作用缺乏理解。此外, 奖赏网络作为TPP中与动机关系最为密切的一个区域, 与其他脑网络之间的关系还不明确。TPP作为一种复杂的社会决策行为, 其激活的脑区广泛而复杂。因此, 有必要将心理和神经层面上的证据整合起来, 形成更加系统的理解。为了从更全面的视角解释TPP行为的发生机制, 本文整合了以往研究结果, 总结梳理个体在TPP中的情绪唤醒、认知过程以及脑区激活模式(文献详细信息见网络版附录表S1), 提出TPP的认知神经网络模型(图3)。在该模型中, 情绪系统和奖赏系统共同作为TPP的动机系统, 负责为TPP行为产生动力, 对应的脑网络分别为突显网络和奖赏网络。社会认知系统和执行控制系统作为认知系统的两个子系统, 参与TPP“责任评估”和“惩罚选择”两个阶段, 对应的脑网络分别为默认模式网络和中央执行网络。模型中各个成分互相配合、相互作用, 最终由执行控制系统做出是否惩罚以及惩罚强度的决策, 由此产生的反馈信息又进一步作用于内部环路, 个体在每一次的反馈中进行学习并形成最优行为决策。对该模型的理解包括以下4个方面:(1)动机系统下的情绪系统和奖赏系统; (2)认知系统内部关系及其对第三方惩罚行为的影响; (3)自动加工与控制加工通路; (4)奖赏网络参与的反馈通路。

4.1 动机系统下的情绪系统和奖赏系统

情绪模型指出, 负性情绪的产生是TPP的动力来源之一(Fehr & G?chter, 2002; Xiao & Houser, 2005), 而互惠模型认为对未来回报的期待(如声誉建立)以及惩罚后的权力体验感、满足感可以作为奖赏信号对个体进行内部强化, 促使个体做出下一次惩罚行为。因此, 情绪和奖赏系统都参与到TPP的动机产生过程中, 并共同组成TPP的动机系统。情绪系统涉及情绪的产生、处理和调节过程(Etkin et al., 2015; Pessoa, 2017)。以往研究发现, 突显网络在TPP中参与情绪加工并指导后续决策(Bellucci et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2016; Mclatchie et al., 2016), 奖赏网络的价值表征和预期奖赏的功能使得其与奖赏系统密切相关(Hu et al., 2015)。因此, 情绪系统和奖赏系统对应的脑网络分别为突显网络和奖赏网络。值得注意的是, 情绪系统和奖赏系统也并非完全独立(箭头5)。情绪系统将负性情绪的产生等情绪信息传递给奖赏系统, 使得个体更倾向于去寻求奖赏性刺激来缓解因负性情绪带来的不适感; 同时, 奖赏系统将以往的奖赏体验(如权力感和满足感)传递给情绪系统, 以此引发积极的情绪体验, 这种相互促进的关系为个体做出惩罚决策提供了动力。

4.2 认知系统内部关系及其对第三方惩罚行为的影响

认知系统包括社会认知系统和执行控制系统。在TPP中, 个体需要根据违规行为信息来评估伤害程度以及推断违规者的心理状态(Ginther et al., 2016; Treadway et al., 2014), 而默认模式网络中与心智化相关的脑区如TPJ和dmPFC在意图推断方面起着重要作用(Feng et al., 2022), 且中央执行网络的核心脑区dlPFC的激活体现了认知控制在TPP中的重要性(殷西乐 等, 2019)。因此, 社会认知系统和执行控制系统与默认模式网络和中央执行网络这两个脑网络相对应, 分别参与“责任评估”和“惩罚选择”两个阶段。有研究者指出, 不同于更多的由情绪驱动的第二方惩罚, TPP者更着重于对违规者的意图推断, 其重要性可能超过情绪(Ginther et al., 2016; Treadway et al., 2014), 这体现了TPP过程中社会认知系统的重要作用。另外, 个体最后是否做出惩罚行为以及惩罚的强度, 又受到执行控制系统的影响。因此, 社会认知系统和执行控制系统对TPP行为的作用是递进式的, 而非相互独立。在神经层面上, Buckholtz等人(2008)首次发现TPJ和dlPFC的活动存在“拮抗”关系:当TPJ活动增加时, dlPFC表现失活, 而当个体决定惩罚时, 其活跃度又增加, 体现了dlPFC的双相神经活动; 此外, Zinchenko等人(2021)的研究也发现, 右侧dlPFC和右侧TPJ之间的整体静息状态连接与TPP水平负相关。任务态和静息态的研究均表明, 默认模式网络(TPJ)和中央执行网络(dlPFC)之间存在“拮抗”关系(箭头6), 更具体地说, dlPFC的这种双相神经活动可能是中央执行网络对默认模式网络抑制作用的基础(Zinchenko & Klucharev, 2017)。同时, 两者间也存在互补性(陈瀛 等, 2020):默认模式网络代表“感性”的社会认知, 反映了由认知和情绪所主导的责任评估; 而中央执行网络通常代表“理性”的逻辑思维, 在认知控制方面的作用体现了大脑中的理性思考与权衡。“感性”与“理性”的结合体现了默认模式网络和中央执行网络在功能上的互补。

4.3 自动加工与控制加工通路

结合上文所提到的双系统模型, 在该模型中存在自动加工和控制加工两条通路(在下文称通路1和通路2)。两条通路均以情绪系统作为起点, 由执行控制系统输出最终的TPP行为。不同的是, 个体观察到违规行为后(箭头1), 通路1中情绪系统直接将整合后的负性情绪传递给认知系统(箭头2), 由执行控制系统执行惩罚决定, 此时个体进行惩罚可能是为了消解负性情绪(箭头4); 而通路2中加入了大脑理性控制的因素, 情绪系统的信息先由社会认知系统进行伤害程度和意图的评估, 再由执行控制系统相关脑区进行情绪和自利的权衡(箭头3), 最终执行惩罚决定(箭头4), 对应着TPP“情绪产生”、“责任评估”和“惩罚选择”三个阶段。

4.4 奖赏网络参与的反馈通路

在TPP决策过程中, 个体需要时刻收集和评估环境信息, 以此来调整行为策略, 这依赖于反馈机制得以实现。具体来说, 当第三方做出惩罚决定之后(箭头4), 负性情绪的消解以及权力的体验感和满足感作为相应的奖励信号正反馈于奖赏系统(箭头7), 为下一次惩罚提供了动力。根据RL理论, 个体从反馈提供的奖励信息中不断学习, 综合考虑各项因素来预估奖赏的最大值, 并最终形成稳定的惩罚模式。由上可知, 反馈机制的存在使TPP行为的发生发展得以顺利进行, 当反馈机制遭到破坏, 个体可能会面临异常的行为, 可见反馈机制在TPP认知神经网络模型中起着关键的作用。

5 总结与展望

本文综述了近10年来的TPP相关研究, 从理论模型和神经网络两个层面对TPP行为的认知神经机制进行总结, 并在前人研究的基础上提出TPP的认知神经网络模型, 从更加宏观的角度展现了TPP行为的发生发展过程和神经关联。在该模型中, 情绪系统和奖赏系统是TPP的动力来源, 认知系统主要负责责任评估以及惩罚的选择, 奖赏网络、突显网络、默认模式网络和中央执行网络分别参与不同认知加工阶段。与此同时, TPP行为反馈机制的存在使得个体会在每一次反馈学习中优化行为策略, 最终形成稳定的行为模式。然而, 目前对于TPP的研究还存在一些不足和尚未解决的问题。

5.1 神经递质和激素对第三方惩罚行为的影响

认知神经系统受到神经递质和激素的影响(Hu, Scheele, et al., 2016)。探究TPP行为、神经递质、激素三者间的关系, 有助于我们从更微观的角度理解TPP行为。本文仅从多巴胺水平及其遗传变异的角度对个体惩罚行为背后的遗传学机理進行了简单剖析, 为揭示TPP行为发生的神经生化基础提供了启示。除多巴胺以外, 一些研究发现5-羟色胺水平低的个体表现出了更多的利他惩罚行为(Emanuele et al., 2008), 且5-HTTLPR L/L基因携带者TPP强度更大(Enge et al., 2017)。然而, Enge等人的研究并未排除多巴胺和5-羟色胺之间相互作用的影响, 对5-羟色胺如何影响TPP行为的机制也尚不明确。在激素水平上, 已有研究证明肽类激素催产素(oxytocin, OXT)与人类的亲社会行为相关(Marsh et al., 2021)。然而目前少有研究探讨外源性OXT与TPP行为的关系。Krueger等人(2012)发现OXT仅仅影响对伤害程度的感知而不影响TPP的强度。总的来说, 目前对神经递质和激素及其基因多态性如何影响TPP行为的研究尚处在初步阶段, 未来从该角度入手有助于从更微观的角度揭示TPP行为的神经生理机制。

5.2 第三方惩罚行为的个体差异

以往的研究大多将样本进行整体性的分析, 忽略了个体之间的差异。例如, 共情作为一种理解和感受他人情绪的能力, 是亲社会行为的动机来源之一, 对TPP行为有着重要影响(Ferguson et al., 2019), 个体在面对更加贫穷的违规者时共情水平更高, 对其宽容度更高, 因此惩罚强度更低(Ouyang et al., 2021)。然而, 共情也存在着巨大的个体差异, 且该差异可能会进一步体现在神经生理反应上(van Baar et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022)。此外, 由于传统的ERP分析对所有的被试数据进行了组平均处理, 最终的结果可能无法反映个体间的差异, 导致人们做出错误的解释(陈新文 等, 2023)。因此, 未来有必要将个体差异如共情、社会价值取向、心智化能力等纳入TPP行为的认知神经机制的研究, 进一步探讨TPP行为的神经生理表征与人格特质变量的关系。

5.3 对第三方惩罚行为做出定量的解释和预测

本文提出的TPP的认知神经网络模型能够在一定程度上预测TPP行为, 但尚停留在定性的层面, 实际TPP行为的产生是否遵循该模式还需要进一步的检验。近年来, 越来越多的研究者将机器学习的方法应用到认知加工领域。以多变量解码分析(multivariate decoding analysis)为例, 该方法可以量化单个神经信号所代表的信息, 并用于训练和测试分类器, 将特定事件所对应的大脑活动信号进行区分(Contini et al., 2017)。这里的神经信号可以来自神经影像学信号如功能磁共振成像(functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI), 也可以来自神经生理学信号如脑电图(electroencephalogram, EEG)和脑磁图(magnetoencephalogram, MEG)。考虑到TPP是一个由多个子阶段组成的复杂社交行为, 利用该方法可以进一步探究与TPP行为相关的复杂神经活动模式。因此, 未来需要进一步优化和发展相关模型, 引入基于机器学习分析方法如多变量解码分析来构建数学模型, 探究个体在不同情况下如不同惩罚代价高低、不同程度的不公平分配方案等的神经信号差异, 以此对TPP行为做出定量的解释和预测。

5.4 第三方惩罚和补偿行为认知神经机制的异同

从建立声誉的角度来看, 第三方个体对违规者做出惩罚表明了他们的合作意图。然而, 当个体有其他更为积极的方式来表达自己合作倾向的时候, 这种通过惩罚而建立的声誉可能是有害的(Raihani & Bshary, 2015a)。具体来讲, 当第三方个体不仅有“惩罚”和“不作为”两个选项, 还引入了“帮助受害者”这一条件时, TPP的利他强度会减弱, 因为此时惩罚会被视为一种竞争性的、“损人不利己”的信号(Jordan, Hoffman, et al., 2016), 而帮助会得到更加积极的评价(Raihani & Bshary, 2015b; Li et al., 2018)。在这种复杂的社交情境下, 引入“第三方干预”就显得尤为重要, 包括第三方惩罚和第三方补偿(帮助)。与惩罚所面对的对象不同, 第三方补偿关注的焦点在受害者, 即第三方个体牺牲自己的利益来补偿受害者, 使其真正受益。已有研究表明, 共情水平越高的个体更容易做出帮助他人的决定, 且帮助和惩罚背后的神经机制也存在异同(Hu et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2022; 苏彦捷 等, 2019)。由于这两种干预形式所关注的焦点不同, 未来的研究可以关注在不同社交情境下个体的第三方干预偏好及其背后的神经机制。

5.5 利用元分析为认知神经网络模型提供统计支撑

本文提出的认知神经网络模型能够在理论上对TPP行为的发生发展做出更加整体、全面的解释, 但还缺乏一定的统计支撑。元分析在定性分析的基础上引入了定量的分析方法, 经该方法得出的结论更具有概括性和普遍性。一方面, TPP的产生包括不同的阶段, 每个阶段所涉及的脑区和网络激活模式也各不相同, 利用元分析能够处理分析大量的单个研究数据, 做到有效的综合(董奇, 2004); 另一方面, 前人在探究TPP的神经心理机制时所采用的实验范式和因变量测量方式各有不同, 这些方法上的变异可能会带来实验结果的不一致, 而元分析能够进一步探索研究中特征变量的异质性来源, 较好地解决这一问题。因此, 未来在理论模型的完善过程中, 可以利用元分析对已有研究结果进行综合分析以及再评价, 为模型提供定量的数据支撑以增加模型的可靠性。

参考文献

陈新文, 李鸿杰, 丁玉珑. (2023). 探究事件相关脑电/脑磁信号中的神經表征模式:基于分类解码和表征相似性分析的方法. 心理科学进展, 31(2), 173?195.

陈瀛, 徐敏霞, 汪新建. (2020). 信任的认知神经网络模型. 心理科学进展, 28(5), 800?809.

董奇. (2004). 心理与教育研究方法 (修订版). 北京师范大学出版社.

刘映杰, 段亚妮, 刘昊馨, 刘佳, 王赫. (2022). 得失情境下第三方惩罚决策差异的神经机制:基于rTMS的研究. 心理科学, 45(4), 942?952.

罗艺, 封春亮, 古若雷, 吴婷婷, 罗跃嘉. (2013). 社会决策中的公平准则及其神经机制. 心理科学进展, 21(2), 300?308.

苏彦捷, 谢东杰, 王笑楠. (2019). 认知控制在第三方惩罚中的作用. 心理科学进展, 27(8), 1331?1343.

唐捷, 黄晓璇, 吴嵩, 崔芳. (2022). 财富越多, 责任越大:资金数量和来源对公共物品困境中第三方惩罚的影响. 心理科学, 45(3), 665?671.

吴燕, 罗跃嘉. (2011). 利他惩罚中的结果评价——ERP研究. 心理学报, 43(6), 661?673.

谢东杰, 苏彦捷. (2019). 第三方惩罚的演化与认知机制. 心理科学, 42(1), 216?222.

杨莎莎, 陈思静. (2022). 第三方惩罚中的规范错觉:基于公正世界信念的解释. 心理学报, 54(3), 281?299.

殷西乐, 李建标, 陈思宇, 刘晓丽, 郝洁. (2019). 第三方惩罚的神经机制:来自经颅直流电刺激的证据. 心理学报, 51(5), 571?583.

张慧, 马红宇, 徐富明, 刘燕君, 史燕伟. (2018). 最后通牒博弈中的公平偏好:基于双系统理论的视角. 心理科学进展, 26(2), 319?330.

张耀华, 林珠梅, 朱莉琪. (2013). 人类的利他性惩罚:认知神经科学的视角. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 40(9), 796?803.

Anne, L., Frank, K., Olga, D. M., Matteo, P., Sarah, J. P., Jeffrey, S., & Jordan, G. (2012). Damage to the left ventromedial prefrontal cortex impacts affective theory of mind. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(8), 871?880.

Asp, E. W., Gullickson, J. T., Warner, K. A., Koscik, T. R., Denburg, N. L., & Tranel, D. (2019). Soft on crime: Patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex damage allocate reduced third-party punishment to violent criminals. Cortex, 119, 33?45.

Baumgartner, T., G?tte, L., R Gügler, & Fehr, E. (2012). The mentalizing network orchestrates the impact of parochial altruism on social norm enforcement. Human Brain Mapping, 33(6), 1452?1469.

Baumgartner, T., Schiller, B., Rieskamp, J., Gianotti, L. R. R., & Knoch, D. (2014). Diminishing parochialism in intergroup conflict by disrupting the right temporo-parietal junction. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(5), 653?660.

Bellucci, G., Camilleri, J. A., Iyengar, V., Eickhoff, S. B., & Krueger, F. (2020). The emerging neuroscience of social punishment: Meta-analytic evidence. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 113, 426?439.

Bellucci, G., Chernyak, S., Hoffman, M., Deshpande, G., Monte, O. D., Knutson, K., Grafman, J., & Krueger, F. (2017). Effective connectivity of brain regions underlying third-party punishment: Functional MRI and Granger causality evidence. Social Neuroscience, 12(2), 124?134.

Bernhard, H., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). Group affiliation and altruistic norm enforcement. American Economic Review, 96(2), 217?221.

Bright, D. A., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2006). Gruesome evidence and emotion: Anger, blame, and jury decision- making. Law and Human Behavior, 30(2), 183?202.

Brüne, M., von Hein, S. M., Claassen, C., Hoffmann, R., & Saft, C. (2021). Altered third-party punishment in Huntington's disease: A study using neuroeconomic games. Brain and Behavior, 11(1), Article e01908.

Buckholtz, J. W., Asplund, C. L., Dux, P. E., Zald, D. H., Gore, J. C., Jones, O. D., & Marois, R. (2008). The neural correlates of third-party punishment. Neuron, 60(5), 930?940.

Buckholtz, J. W., & Marois, R. (2012). The roots of modern justice: Cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 655? 661.

Buckholtz, J. W., Martin, J. W., Treadway, M. T., Jan, K., Zald, D. H., Jones, O., & Marois, R. (2015). From blame to punishment: Disrupting prefrontal cortex activity reveals norm enforcement mechanisms. Neuron, 87(6), 1369?1380.

Cheng, X., Zheng, L., Liu, Z., Ling, X., Wang, X., Ouyang, H., Chen, X., Huang, D., & Guo, X. (2022). Punishment cost affects third-parties behavioral and neural responses to unfairness. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 177, 27?33.

Chung, J. C. Y., Bhatoa, R. S., Kirkpatrick, R., & Woodcock, K. A. (2023). The role of emotion regulation and choice repetition bias in the ultimatum game. Emotion, 23(4), 925?936

Ciaramidaro, A., Toppi, J., Casper, C., Freitag, C. M., Siniatchkin, M., & Astolfi, L. (2018). Multiple-brain connectivity during third party punishment: An EEG hyperscanning study. Scientific Reports, 8(1), Article 6822.

Civai, C. (2013). Rejecting unfairness: Emotion-driven reaction or cognitive heuristic? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, Article 126.

Civai, C., Crescentini, C., Rustichini, A., & Rumiati, R. I. (2012). Equality versus self-interest in the brain: Differential roles of anterior insula and medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage, 62(1), 102?112.

Civai, C., Huijsmans, I., & Sanfey, A. G. (2019). Neurocognitive mechanisms of reactions to second- and third-party justice violations. Scientific Reports, 9(1), Article 9271.

Contini, E. W., Wardle, S. G., & Carlson, T. A. (2017). Decoding the time-course of object recognition in the human brain: From visual features to categorical decisions. Neuropsychologia, 105, 165?176.

Craig, A. D. B. (2009). How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(1), 59?70.

Cui, F., Wang, C., Cao, Q., & Jiao, C. (2019). Social hierarchies in third-party punishment: A behavioral and ERP study. Biological Psychology, 146, Article 107722.

Cui, F., Wu, S., Wu, H., Wang, C., Jiao, C., & Luo, Y. (2018). Altruistic and self-serving goals modulate behavioral and neural responses in deception. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(1), 63?71.

de Quervain, D. J., Fischbacher, U., Treyer, V., Schellhammer, M., Schnyder, U., Buck, A., & Fehr, E. (2004). The neural basis of altruistic punishment. Science, 305(5688), 1254? 1258.

Delgado, M. R., Locke, H. M., Stenger, V. A., & Fiez, J. A. (2003). Dorsal striatum responses to reward and punishment: Effects of valence and magnitude manipulations. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 3(1), 27?38.

Emanuele, E., Brondino, N., Bertona, M., Re, S., & Geroldi, D. (2008). Relationship between platelet serotonin content and rejections of unfair offers in the ultimatum game. Neuroscience Letters, 437(2), 158?161.

Enge, S., Mothes, H., Fleischhauer, M., Reif, A., & Strobel, A. (2017). Genetic variation of dopamine and serotonin function modulates the feedback-related negativity during altruistic punishment. Scientific Reports, 7(1), Article 2996.

Etkin, A., Büchel, C., & Gross, J. J. (2015). The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(11), 693?700.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425(6960), 785?791.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004a). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(2), 63?87.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004b). Social norms and human cooperation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(4), 185?190.

Fehr, E., & G?chter, S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature, 415(6868), 137?140.

Fehr, E., & Schurtenberger, I. (2018). Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(7), 458?468.

Feng, C., Deshpande, G., Liu, C., Gu, R., Luo, Y. J., & Krueger, F. (2016). Diffusion of responsibility attenuates altruistic punishment: A functional magnetic resonance imaging effective connectivity study. Human Brain Mapping, 37(2), 663?677.

Feng, C., Yang, Q., Azem, L., Atanasova, K. M., Gu, R., Luo, W., Hoffman, M., Lis, S., & Krueger, F. (2022). An fMRI investigation of the intention-outcome interactions in second- and third-party punishment. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 16(2), 715?727.

Ferguson, E., Quigley, E., Powell, G., Stewart, L., Harrison, F., & Tallentire, H. (2019). To help or punish in the face of unfairness: Men and women prefer mutually-beneficial strategies over punishment in a sexual selection context. Royal Society Open Science, 6(9), Article 181441.

Gershman, S. J., Markman, A. B., & Otto, A. R. (2014). Retrospective revaluation in sequential decision making: A tale of two systems. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(1), 182?194.

Ginther, M. R., Bonnie, R. J., Hoffman, M. B., Shen, F. X., Simons, K. W., Jones, O. D., & Marois, R. (2016). Parsing the behavioral and brain mechanisms of third-party punishment. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(36), 9420?9434.

Glass, L., Moody, L., Grafman, J., & Krueger, F. (2016). Neural signatures of third-party punishment: Evidence from penetrating traumatic brain injury. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(2), 253?262.

Guala, F. (2012). Reciprocity: Weak or strong? What punishment experiments do (and do not) demonstrate. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35(1), 1?15.

Hu, J., Blue, P. R., Yu, H., Gong, X., Xiang, Y., Jiang, C., & Zhou, X. (2016). Social status modulates the neural response to unfairness. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(1), 1?10.

Hu, Y., Scheele, D., Becker, B., Voos, G., David, B., Hurlemann, R., & Weber, B. (2016). The effect of oxytocin on third-party altruistic decisions in unfair situations: An fMRI study. Scientific Reports, 6, Article 20236.

Hu, Y., Strang, S., & Weber, B. (2015). Helping or punishing strangers: Neural correlates of altruistic decisions as third- party and of its relation to empathic concern. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, Article 24.

Ikemoto, S. (2010). Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: A neurobiological theory. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(2), 129?150.

Jamali, M., Grannan, B. L., Fedorenko, E., Saxe, R., Báez- Mendoza, R., & Williams, Z. M. (2021). Single-neuronal predictions of others' beliefs in humans. Nature, 591(7851), 610?614.

Johnson, R., Henkell, H., Simon, E., & Zhu, J. (2008). The self in conflict: The role of executive processes during truthful and deceptive responses about attitudes. NeuroImage, 39(1), 469?482.

Jordan, J. J., Hoffman, M., Bloom, P., & Rand, D. G. (2016). Third-party punishment as a costly signal of trustworthiness. Nature, 530(7591), 473?476.

Jordan, J., McAuliffe, K., & Rand, D. (2016). The effects of endowment size and strategy method on third party punishment. Experimental Economics, 19(4), 741?763.

Kanakogi, Y., Miyazaki, M., Takahashi, H., Yamamoto, H., Kobayashi, T., & Hiraki, K. (2022). Third-party punishment by preverbal infants. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(9), 1234?1242.

Kim, M., Decety, J., Wu, L., Baek, S., & Sankey, D. (2021). Neural computations in childrens third-party interventions are modulated by their parents moral values. NPJ Science of Learning, 6(1), Article 38.

Knoch, D., Nitsche, M. A., Fischbacher, U., Eisenegger, C., Pascual-Leone, A., & Fehr, E. (2008). Studying the neurobiology of social interaction with transcranial direct current stimulation—The example of punishing unfairness. Cerebral Cortex, 18(9), 1987?1990.

Knoch, D., Pascual-Leone, A., Meyer, K., Treyer, V., & Fehr, E. (2006). Diminishing reciprocal fairness by disrupting the right prefrontal cortex. Science, 314(5800), 829?832.

Konishi, N., & Ohtsubo, Y. (2015). Does dishonesty really invite third-party punishment? Results of a more stringent test. Biology Letters, 11(5), Article 20150172.

K?ster, R., Hadfield-Menell, D., Everett, R., Weidinger, L., Hadfield, G. K., & Leibo, J. Z. (2022). Spurious normativity enhances learning of compliance and enforcement behavior in artificial agents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(3), Article e2106028118.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77?124.

Krueger, F., & Hoffman, M. (2016). The emerging neuroscience of third-party punishment. Trends in Neurosciences, 39(8), 499?501.

Krueger, F., Parasuraman, R., Moody, L., Twieg, P., de Visser, E., Mccabe, K., OHara, M., & Lee, M. (2012). Oxytocin selectively increases perceptions of harm for victims but not the desire to punish offenders of criminal offenses. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(5), 494?498.

Lee, S. W., Shimojo, S., & ODoherty, J. P. (2014). Neural computations underlying arbitration between model-based and model-free learning. Neuron, 81(3), 687?699.

Lergetporer, P., Angerer, S., Gl?tzle-Rützler, D., & Sutter, M. (2014). Third-party punishment increases cooperation in children through (misaligned) expectations and conditional cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(19), 6916? 6921.

Li, J., Li, S., Wang, P., Liu, X., Zhu, C., Niu, X., Wang, G., & Yin, X. (2018). Fourth-party evaluation of third-party pro-social help and punishment: An ERP study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 932.

Liu, Y., Bian, X., Hu, Y., Chen, Y.-T., Li, X., & Di Fabrizio, B. (2018). Intergroup bias influences third-party punishment and compensation: In-group relationships attenuate altruistic punishment. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(8), 1397?1408.

Lo Gerfo, E., Gallucci, A., Morese, R., Vergallito, A., Ottone, S., Ponzano, F., Locatelli, G., Bosco, F., & Romero Lauro, L. J. (2019). The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal junction in third-party punishment behavior. NeuroImage, 200, 501?510.

Lockwood, P. L., Apps, M. A. J., Valton, V., Viding, E., & Roiser, J. P. (2016). Neurocomputational mechanisms of prosocial learning and links to empathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(35), 9763?9768.

Marsh, N., Marsh, A. A., Lee, M. R., & Hurlemann, R. (2021). Oxytocin and the neurobiology of prosocial behavior. The Neuroscientist, 27(6), 604?619.

Martin, J. W., Martin, S., & McAuliffe, K. (2021). Third-party punishment promotes fairness in children. Developmental psychology, 57(6), 927?939.

McAuliffe, K., Jordan, J. J., & Warneken, F. (2015). Costly third-party punishment in young children. Cognition, 134, 1?10.

Mclatchie, N., Giner-Sorolla, R., & Derbyshire, S. W. G. (2016). ‘Imagined guilt vs ‘recollected guilt: Implications for fMRI. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(5), 703?711.

Meidenbauer, K. L., Cowell, J. M., & Decety, J. (2018). Childrens neural processing of moral scenarios provides insight into the formation and reduction of in‐group biases. Developmental Science, 21(6), Article e12676.

Menon, V., & Uddin, L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Structure and Function, 214(5?6), 655?667.

Moll, J., de Oliveira-Souza, R., Basilio, R., Bramati, I. E., Gordon, B., Rodríguez-Nieto, G., ... Grafman, J. (2018). Altruistic decisions following penetrating traumatic brain injury. Brain, 141(5), 1558?1569.

Morese, R., Rabellino, D., Sambataro, F., Perussia, F., Valentini, M. C., Bara, B. G., & Bosco, F. M. (2016). Group membership modulates the neural circuitry underlying third party punishment. PLoS One, 11(11), Article e0166357.

Morris, A., MacGlashan, J., Littman, M. L., & Cushman, F. (2017). Evolution of flexibility and rigidity in retaliatory punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(39), 10396?10401.

Mothes, H., Enge, S., & Strobel, A. (2016). The interplay between feedback-related negativity and individual differences in altruistic punishment: An EEG study. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 16(2), 276?288.

Mussel, P., Hewig, J., & Wei?, M. (2018). The reward-like nature of social cues that indicate successful altruistic punishment. Psychophysiology, 55(9), Article e13093.

Naqvi, N., Shiv, B., & Bechara, A. (2006). The role of emotion in decision making: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 260?264.

Nelissen, R. M. A., & Zeelenberg, M. (2009). Moral emotions as determinants of third-party punishment: Anger, guilt, and the functions of altruistic sanctions. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(7), 543?553.

ODoherty, J., Dayan, P., Schultz, J., Deichmann, R., Friston, K., & Dolan, R. J. (2004). Dissociable roles of ventral and dorsal striatum in instrumental conditioning. Science, 304(5669), 452?454.

Ouyang, H., Yu, J., Duan, J., Zheng, L., Li, L., & Guo, X. (2021). Empathy-based tolerance towards poor norm violators in third-party punishment. Experimental Brain Research, 239(7), 2171?2180.

Pedersen, E. J., McAuliffe, W. H. B., & McCullough, M. E. (2018). The unresponsive avenger: More evidence that disinterested third parties do not punish altruistically. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(4), 514?544.

Pessoa, L. (2017). A network model of the emotional brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(5), 357?371.

Piazza, J., & Bering, J. M. (2008). The effects of perceived anonymity on altruistic punishment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(3), 487?501.

Qu, L., Dou, W., You, C., & Qu, C. (2014). The processing course of conflicts in third-party punishment: An event-related potential study. Psychology Journal, 3(3), 214?221.

Rahal, R.-M., & Fiedler, S. (2022). Cognitive and affective processes of prosociality. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 309?314.

Rai, T. S. (2022). Material benefits crowd out moralistic punishment. Psychological Science, 33(5), 789?797.

Raihani, N. J., & Bshary, R. (2015a). The reputation of punishers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30(2), 98?103.

Raihani, N. J., & Bshary, R. (2015b). Third-party punishers are rewarded, but third-party helpers even more so. Evolution, 69(4), 993?1003.

Raihani, N. J., & McAuliffe, K. (2012). Human punishment is motivated by inequity aversion, not a desire for reciprocity. Biology Letters, 8(5), 802?804.

Rothschild, Z. K., & Keefer, L. A. (2018). Righteous or self- righteous anger? Justice sensitivity moderates defensive outrage at a third-party harm-doer. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 507?522.

Ruff, C. C., & Fehr, E. (2014). The neurobiology of rewards and values in social decision making. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(8), 549?562.

Sanfey, A. G., Rilling, J. K., Aronson, J. A., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2003). The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science, 300(5626), 1755?1758.

Schultz, W. (2007). Behavioral dopamine signals. Trends in Neurosciences, 30(5), 203?210.

Schultz, W. (2013). Updating dopamine reward signals. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(2), 229?238.

Shenhav, A., Cohen, J. D., & Botvinick, M. M. (2016). Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the value of control. Nature Neuroscience, 19(10), 1286?1291.

Singer, T., Critchley, H. D., & Preuschoff, K. (2009). A common role of insula in feelings, empathy and uncertainty. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(8), 334?340.

Stallen, M., Rossi, F., Heijne, A., Smidts, A., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Sanfey, A. G. (2018). Neurobiological mechanisms of responding to injustice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(12), 2944?2954.

Strobel, A., Zimmermann, J., Schmitz, A., Reuter, M., Lis, S., Windmann, S., & Kirsch, P. (2011). Beyond revenge: Neural and genetic bases of altruistic punishment. NeuroImage, 54(1), 671?680.

Sun, L., Tan, P., Cheng, Y., Chen, J., & Qu, C. (2015). The effect of altruistic tendency on fairness in third-party punishment. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 820.

Thaler, R. H. (1988). Anomalies: The ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(4), 195?206.

Treadway, M. T., Buckholtz, J. W., Martin, J. W., Jan, K., Asplund, C. L., Ginther, M. R., Jones, O. D., & Marois, R. (2014). Corticolimbic gating of emotion-driven punishment. Nature Neuroscience, 17(9), 1270?1275.

van Baar, J. M., Halpern, D. J., & FeldmanHall, O. (2021). Intolerance of uncertainty modulates brain-to-brain synchrony during politically polarized perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(20), Article e2022491118.

van der Helden, J., Boksem, M. A. S., & Blom, J. H. G. (2010). The importance of failure: Feedback-related negativity predicts motor learning efficiency. Cerebral Cortex, 20(7), 1596?1603.

Wang, L., Lu, X., Gu, R., Zhu, R., Xu, R., Broster, L. S., & Feng, C. (2017). Neural substrates of context- and person- dependent altruistic punishment. Human Brain Mapping, 38(11), 5535?5550.

Wang, R., Yu, R., Tian, Y., & Wu, H. (2022). Individual variation in the neurophysiological representation of negative emotions in virtual reality is shaped by sociability. NeuroImage, 263, Article 119596.

Wise, R. A., & Rompre, P.-P. (1989). Brain dopamine and reward. Annual Review of Psychology, 40(1), 191?225.

Wu, Y., Leliveld, M. C., & Zhou, X. (2011). Social distance modulates recipients fairness consideration in the dictator game: An ERP study. Biological Psychology, 88(2), 253? 262.

Xiao, E., & Houser, D. (2005). Emotion expression in human punishment behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(20), 7398?7401.

Xie, E., Liu, M., Liu, J., Gao, X., & Li, X. (2022). Neural mechanisms of the mood effects on third‐party responses to injustice after unfair experiences. Human Brain Mapping, 43(12), 3646?3661.

Xie, H., Karipidis, I. I., Howell, A., Schreier, M., Sheau, K. E., Manchanda, M. K., ... Saggar, M. (2020). Finding the neural correlates of collaboration using a three-person fMRI hyperscanning paradigm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(37), 23066?23072.

Yamagishi, T., Li, Y., Fermin, A. S. R., Kanai, R., Takagishi, H., Matsumoto, Y., Kiyonari, T., & Sakagami, M. (2017). Behavioural differences and neural substrates of altruistic and spiteful punishment. Scientific Reports, 7(1), Article 14654.

Yang, C., Xiao, K., Ao, Y., Cui, Q., Jing, X., & Wang, Y. (2023). The thalamus is the causal hub of intervention in patients with major depressive disorder: Evidence from the Granger causality analysis. NeuroImage: Clinical, 37, Article 103295.

Yang, J., Gu, R., Liu, J., Deng, K., Huang, X., Luo, Y. J., & Cui, F. (2022). To blame or not? Modulating third-party punishment with the framing effect. Neuroscience Bulletin, 38(5), 533?547.

Yang, Q., Shao, R., Zhang, Q., Li, C., Li, Y., Li, H., & Lee, T. (2019). When morality opposes the law: An fMRI investigation into punishment judgments for crimes with good intentions. Neuropsychologia, 127, 195?203.

Yang, Z., Zheng, Y., Yang, G., Li, Q., & Liu, X. (2019). Neural signatures of cooperation enforcement and violation: A coordinate-based meta-analysis. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 14(9), 919?931.

Zhao, Y., Wang, D., Wang, X., & Chiu, S. C. (2022). Brain mechanisms underlying the influence of emotions on spatial decision-making: An EEG study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, Article 989988.

Zhong, S., Chark, R., Hsu, M., & Chew, S. H. (2016). Computational substrates of social norm enforcement by unaffected third parties. NeuroImage, 129, 95?104.

Zhou, Y., Jiao, P., & Zhang, Q. (2017). Second-party and third-party punishment in a public goods experiment. Applied Economics Letters, 24(1), 54?57.

Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Rao, L. L., Yang, L. Q., & Li, S. (2014). Money talks: Neural substrate of modulation of fairness by monetary incentives. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, Article 150.

Zinchenko, O., Belianin, A., & Klucharev, V. (2019). The role of the temporoparietal and prefrontal cortices in a third-party punishment: A tDCS study. Psychology: Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 16(3), 529?550.

Zinchenko, O., & Klucharev, V. (2017). Commentary: The emerging neuroscience of third-party punishment. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, Article 512.

Zinchenko, O., Nikulin, V., & Klucharev, V. (2021). Wired to punish? Electroencephalographic study of the resting- state neuronal oscillations underlying third-party punishment. Neuroscience, 471, 1?10.

The cognitive and neural mechanism of third-party punishment

Abstract: Third-party punishment (TPP) refers to the punitive behaviors that individuals impose on violators as third parties or observers in order to uphold social norms. Many studies have provided insight into the neural mechanisms underlying TPP behavior. However, few studies have focused on the overall role of functional brain networks. This paper reviews the researches related to TPP in the past decade and summarizes the relevant theoretical models and brain networks. Based on the previous studies, we propose a cognitive neural network model of TPP, which could systematically explain and integrate the neural mechanisms behind TPP behavior. In this model, the affective and reward systems are the TPP power sources, and the cognitive system is mainly responsible for responsibility assessment as well as punishment selection. The reward network, the salient network, the default mode network and the central executive network are involved in different cognitive processing stages, respectively. The model establishes the connection between TPP behavior-related research at the psychological and the cognitive-neural level and provides a more holistic and comprehensive explanation of the mechanisms of TPP behavior. In the future, it is necessary to use meta-analysis or machine learning algorisms in order to explore third-party intervention preferences and the underlying cognitive neural mechanisms in different contextual information and more complex social contexts.

Keywords: third-party punishment, cognitive neural mechanisms, brain network, fMRI