两个大都市景观的愿景:米兰和杭州的国土断面比较方法

(比利时)克里斯蒂安·诺尔夫 (比利时)弗洛伦斯·范诺贝克 严诗忆 谢雨婷*

1 什么是大都市景观?

自20世纪70年代以来,生态学研究使用“大都市景观”的概念来界定广大城市化地区的环境问题[1]。后来,这一术语逐渐拥有了更全面的含义,用来描述超越正式城乡范畴的当代城市化地区的混合、动态的空间状况。空间规划师Peter Bosselmann[2]将大都市景观视为21世纪发达国家存在的城市现象,将其定义为没有明确结构的、孤立发展格局的异质拼贴。此外,他还将大都市景观的出现归因为增长、衰退和浪费驱动下的无规划的、突发的结果。Van den Brink等[3]研究了西欧同样存在的城市现象,呼吁在大都市景观中重新思考当代城市地区的景观含义。景观不再被理解为建成空间以外的开放空间,而是“在大都市生活的影响下,将建筑和非建筑空间结合在一起的(居住)环境中的基底”[3]。随着城市化在世界范围内的持续蔓延[4],大都市景观的包容性概念将越来越适用于描述城市地区的混合状况并用于解决这些地区面临的环境挑战。

2 为什么比较大都市景观?

世界各地的大都市景观都面临着普适性的问题。这些问题一方面源于城市化本身导致的农田侵占、对淡水和空气等自然资源造成压力等消极影响[3,5],另一方面源于气候变化,它打破了城市地区赖以发展的脆弱生态环境平衡。为了减轻与气候相关的洪水风险、热浪和日益加剧的水资源压力,许多大城市正在制定雄心勃勃的城市林业、循环水系统和可再生能源计划[6-7]①。

在全球气候变化的紧迫背景下,大都市景观的概念不再局限于土地利用或肌理问题,而是越来越多地与能够在城市化区域维持良好生活条件的基础设施规划联系在一起。为此,对不同背景下的大都市景观进行交叉比较,可以深入了解它们共同面临的环境挑战以及在适应性策略方面的共同经验教训。

城市之间的实证比较一直是空间研究的经典内容,特别是在城市形态研究领域[8]。Camillo Sitte的《城市建设艺术》(The Art of Building Cities)[9]和Allan B.Jacobs的《伟大的街道》(Great Streets)[10]等具有影响力的研究,通过对多案例的系统比较来识别类型学或得出具有普适性的设计原则。其他学者也使用2个案例的比较来强调模式之间的差异,例如Rowe和Koetter[11]在《拼贴城市》(Collage City)中比较了传统和现代城市的城市肌理,Kühn[12]区分了绿带及绿心这2个规划概念。

在过去20年中,全球范围内多源地理空间数据集、卫星图片和街景的开发极大地促进了不同地域的比较研究[13]。这些国际数据库被用于跨地区的城市设计参数绩效评估[14],或城市化与环境挑战之间的长时序相互作用研究[15-16]。虽然这些国际数据集为比较研究带来了前所未有的资源,我们仍需要谨慎地使用它们,以避免由此可能引发的过度简化和普遍主义的风险。

3 为什么比较米兰与杭州?

米兰和杭州是欧洲和中国最具活力的大都市区之一。虽然2座城市相距9 000多千米,却有一些相似之处。作为位于山区和农业平原之间繁荣的经济中心,这2座城市迅速发展,形成了大都市圈[17-18]。米兰和杭州分别拥有800万(都市区)和1 000万(主城区)居民,如今这2个大都市均面临着洪水频发、水资源短缺、生物多样性丧失和粮食安全等紧迫的问题,其可持续发展面临着巨大挑战[19-20]。

为了回应这些挑战,米兰和杭州均开始制定战略性的国土空间规划,将其城市化与大都市景观作为一个整体的结构化系统进行协调。《米兰2030年总体规划》(Great Milan 2030)和相关的“大都市公园”(“Metropolitan Park”)愿景[21]在许多方面与目前中国的优先发展目标相呼应。杭州作为长三角地区的主要城市,根据国家“生态文明”战略修订了《杭州国土空间总体规划(2021—2035年)》。这可以看作是当代中国城市规划中景观扮演的角色在发生变化的生动案例。

本研究对米兰和杭州大都市进行比较的目的包括2个方面:1)从相互学习的视角找出景观特征、趋势、挑战和机遇的潜在相似之处;2)通过双联画来突出每个大都市的特殊性。在风景园林和城市设计跨国教育项目的框架下,这种比较练习为未来的空间设计师提供了对大都市景观的系统性和批判性理解。同时,研究成果在传播后也可能会引起2个大都市区的决策者和规划师的兴趣。

4 如何比较大都市景观?

如果大都市景观在定义上是模糊且难以描述的,那么如何表现与分析大都市景观成为一个棘手的问题。对此,Bosselmann[2]回顾了国土断面作为一种描述大都市景观方法的优点。该方法在18世纪由Alexander von Humboldt等生物地理学家开发,用于监测特定区域内动、植物的空间分布,此后在其他学科中得到了广泛的应用[22]。在环境规划理论中,Patrick Geddes提出著名的河谷剖面理论(Valley Section)[23],表达了城市与其所在区域的相互依存关系。在景观规划领域,Ian McHarg的开创性著作《设计结合自然》(Design with Nature)[24]采用断面来剖析城市化、自然地理和生态系统之间的关系。最近,在城市规划和设计领域,新城市主义(New Urbanism,假设城市呈中心辐射同心圆布局)使用断面作为一种阐释性模型,将从城市到农村的过渡可视化为6个密度递减的区域[25]。除了剖面视图,Bosselmann[2]在对都市圈的分析中结合平面视图,使用50 km×50 km、4 km×4 km和1 km×1 km的框架绘制分层图底关系图这一形态学分析技术,来辨别水系、街区和街道的布局以及农业的格局。

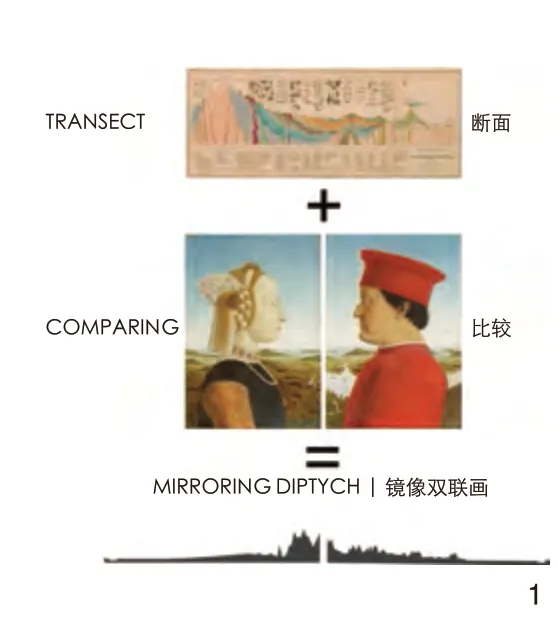

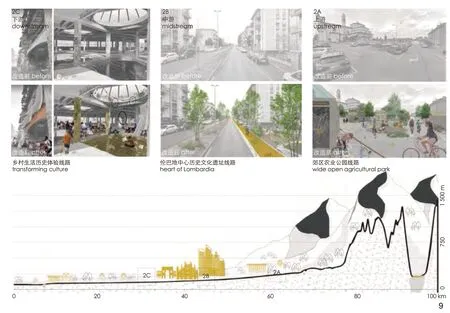

因此,将不同尺度的剖面视图和平面视图相结合的国土断面可以为诠释和可视化不同的景观特征提供新技术。国土断面描绘了城市化与场地自然地理特征之间的联系,其中不同尺度的平面视图有助于解读构成大都市景观的系统和元素的空间格局分布。在这个研究设计项目中,我们将国土断面与城市形态学研究方法相结合,对2个大都市景观进行比较研究,并想象它们的未来(图1)。研究方法主要分为4个步骤。

图1 用于生成镜像双联画的国土断面比较方法The comparative territorial transect method for generating a mirroring diptych

4.1 界定框架

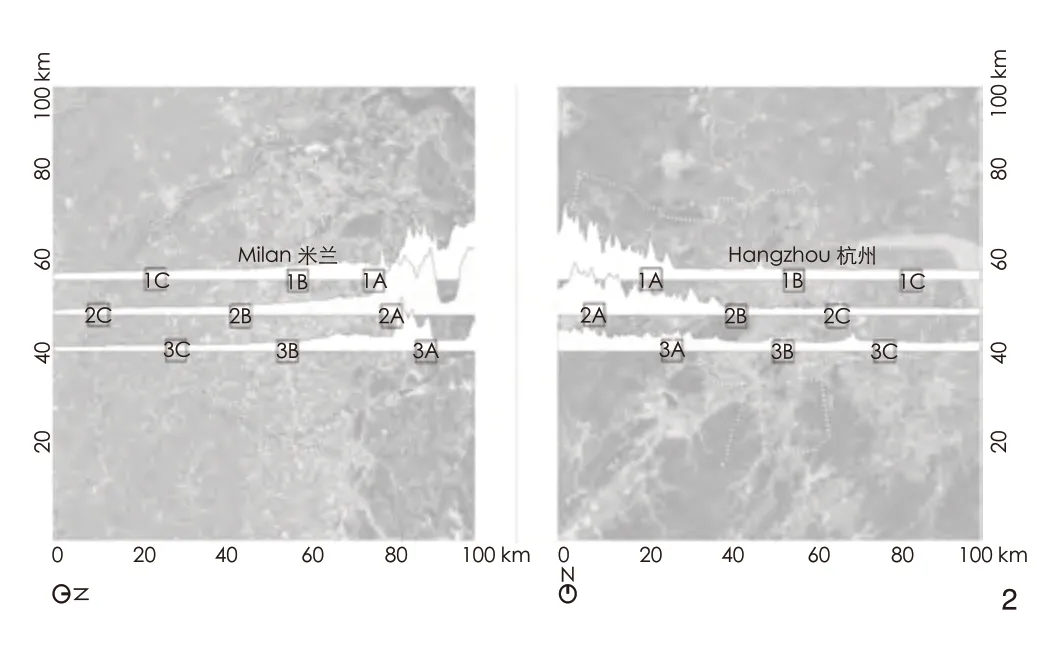

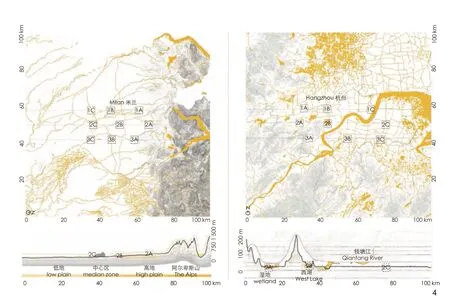

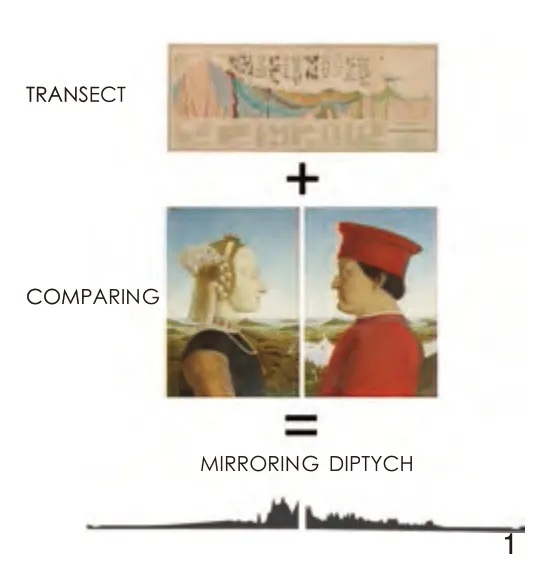

首先,我们为2个研究区域界定了研究范围。研究范围需涵盖该区域的典型自然地理特征,并将行政边界也纳入考量。对于米兰和杭州来说,100 km×100 km的框架(XL尺度,1∶10万)是合理的,它涵盖米兰和杭州大都市区的上游山脉到下游主要河流(图2)。在XL方形框架内,绘制3个100 km的国土断面并沿着每个断面选择3个4 km×4 km的样本区域(L尺度,1∶5 000),这些区域呈现不同的景观结构、模式、城市肌理和密度。

图2 米兰和杭州的100 km×100 km空间框架,3个100 km的断面和9个样本区域The same spatial framework, composed of a 100 km×100 km frame, three transects, and 9 sample areas, was defined to compare Milan and Hangzhou

4.2 专题研究

其次,我们将大都市景观划分为4个专题层:水、生态、生产和文化景观。每一层都从共时和历时的角度进行研究:前一种视角强调了当今大都市区的多样化空间格局;后一种视角基于历史地图和卫星地图的对比揭示每一层的演变。

4.3 专题设计策略

再次,基于空间分析和每个专题层的演变,确定当前的挑战,并提出一系列的设计策略作为回应。

4.4 镜像双联画的比较研究

最后,比较这2个大都市景观。位于米兰和杭州的2个团队,使用相同的开源国际数据库(OpenStreetMap和Google Earth),并应用相同的空间和专题研究框架,比较各自场地的空间演变、挑战和设计策略。研究结果以镜像双联画的形式呈现,并在定期会议上进行讨论。

5 研究结果

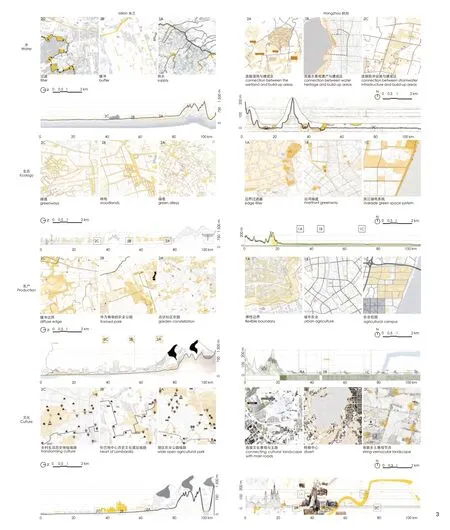

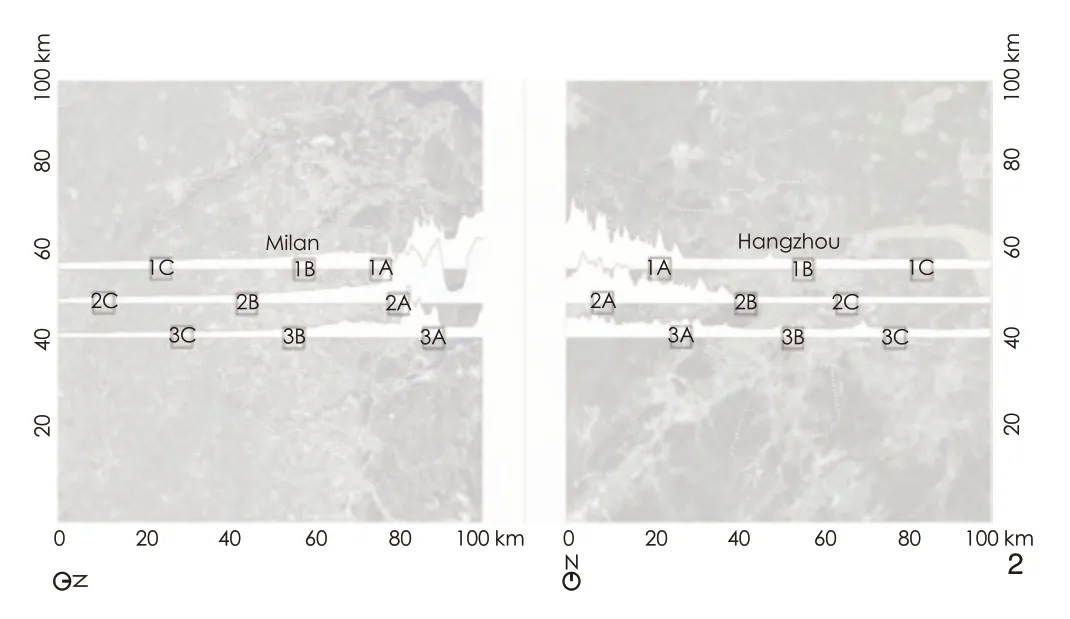

对米兰和杭州大都市景观的探索和比较揭示了两者之间的相似之处和独特之处(图3)。

图3 米兰和杭州大都市的国土断面及专题设计策略Overview of the territorial transects and thematic design strategies in each metropolitan context

5.1 水景观

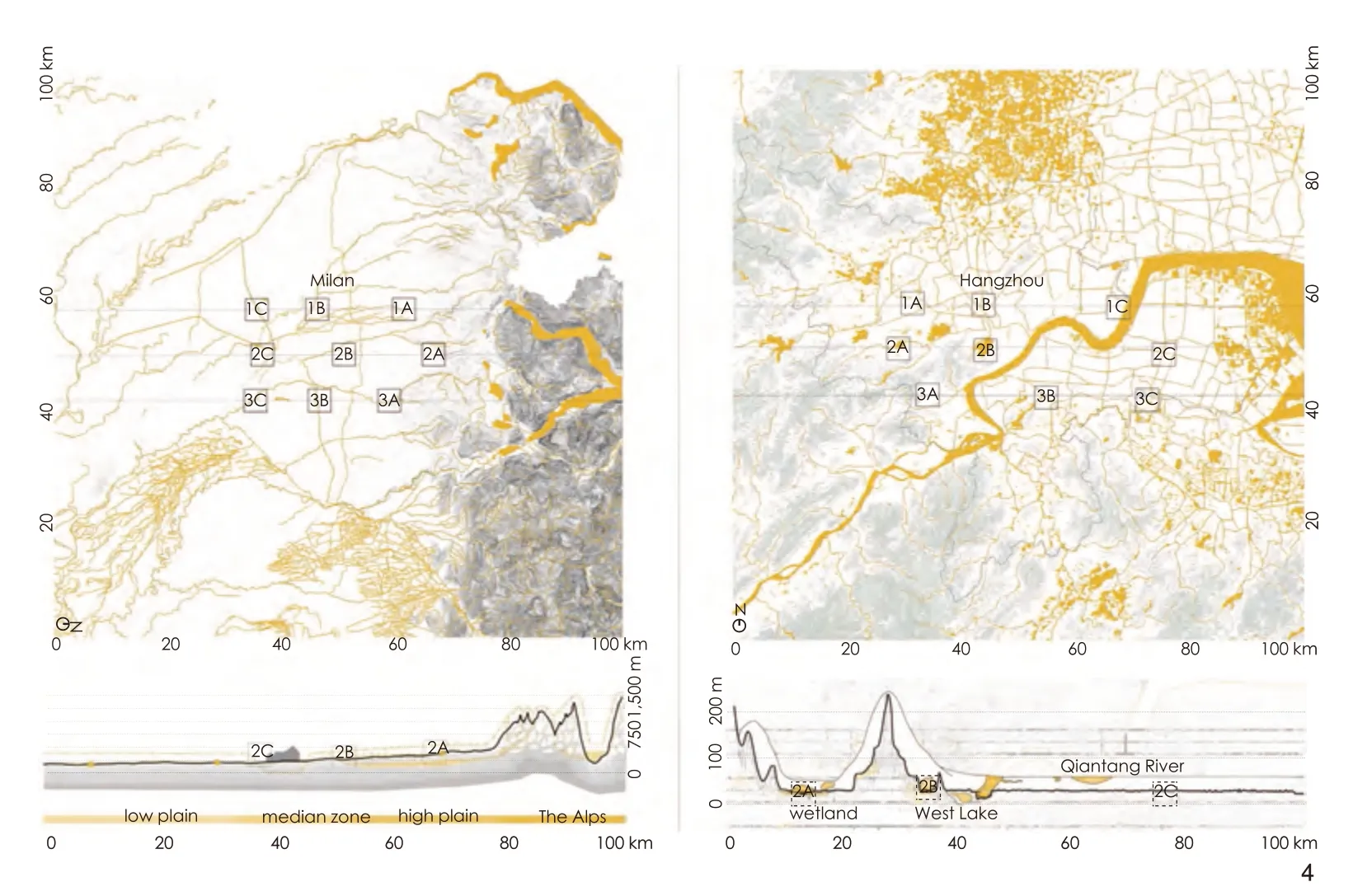

米兰和杭州都是由水塑造的,这一点在如今的杭州表现得尤为明显。杭州仍以著名的西湖、西溪湿地、大运河和密集的水系为特色,这些水系勾勒了城市街区和农村地块。虽然米兰的水景观如今已逐渐消失,但在历史上水要素曾决定了这座城市的基础和发展。米兰这个名字来源于拉丁文“Mediolanum”(土地的中间),指的是干旱平原和湿润平原的交汇处,那里的天然泉水吸引了最早的定居点和纺织活动。米兰的水系是由3条发源于阿尔卑斯山脉的南北向季节性河流和东西向的纳维格里奥运河系统(意大利文:Navigli)构成的,然而如今大多数水系已被渠化或部分覆盖。

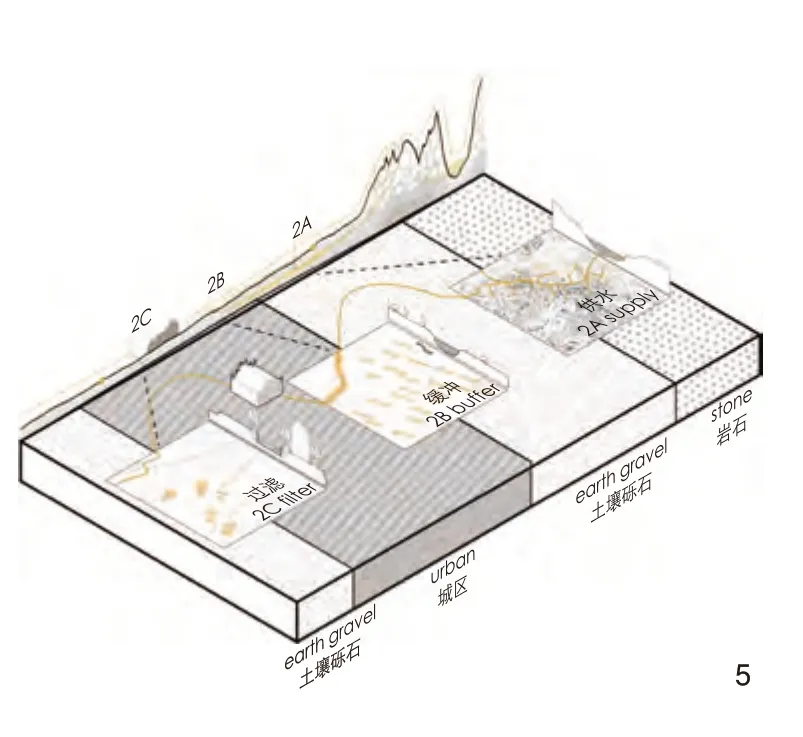

米兰和杭州面临的主要水资源挑战是使排水系统适应城市化和气候变化的影响。为应对这一挑战,米兰水景观专题研究基于集水区的水过程(图4),针对3个4 km×4 km的样本区域,分别提出供水、缓冲和过滤3种设计策略:上游分梯度减缓水流以增加渗透和储水;中游城市地区增设生态植草沟削减地表径流;下游利用高差汇水至城市边界,经过滤后用于农业灌溉,并最终汇入下游的河流(图5)。这些策略同时也激活了水系周边的开放空间,使水在城市中更加可见(图6)。杭州L尺度的水景观图析显示水系存在渠化、连通性差等问题,在3个样本区域分别提议将湿地作为缓冲区连接建成区与乡村、复现部分历史水系以连接历史建筑与湖滨空间、升级农田水系周边的开放空间使其兼具游憩功能,使不同水体在未来城市发展中发挥结构性作用。

图4 XL尺度米兰和杭州水系的对比Comparative mapping of the water systems of Milan and Hangzhou at the XL scale

图5 针对米兰水系统的供水、缓冲和过滤策略Three strategies for Milan’s water system: supply, buffer,filter

图6 针对上游、中游和下游的米兰水系统设计策略Design strategies for Milan’s water system from upstream, midstream to downstream6-1 3个样本区域的水系统设计平面图和断面图Design plans and cross-sections for three sample areas’ water systems6-2 上游储水和过滤水池、中游街道生态植草沟和下游城市边界人工湿地改造前后对比Before and after renovation: water storage and filtration collectors in the upstream, streets’ bioretention swales in the midstream, and constructed wetlands along the urban boundary in the downstream

5.2 生态景观

米兰和杭州的生态景观在断面上呈现不对称的轮廓(图3)。米兰的历史城区位于较低的海拔,介于下游的农业湿润平原(南部农业公园,意大利文:Parco Agricolo Sud)和干旱平原之间,在干旱平原上,城市延伸了数十千米,直至阿尔卑斯山脉。杭州的历史城区位于山脚下,城市化在冲积平原下游展开。然而,在这2个大都市区中,城市化区域均侵占了先前的农业景观,导致了生态空间的破碎化[19,26]。因此,如今亟须在区域尺度上恢复生态空间的连通性,遏制城市的进一步扩张并提高城市的生活品质。

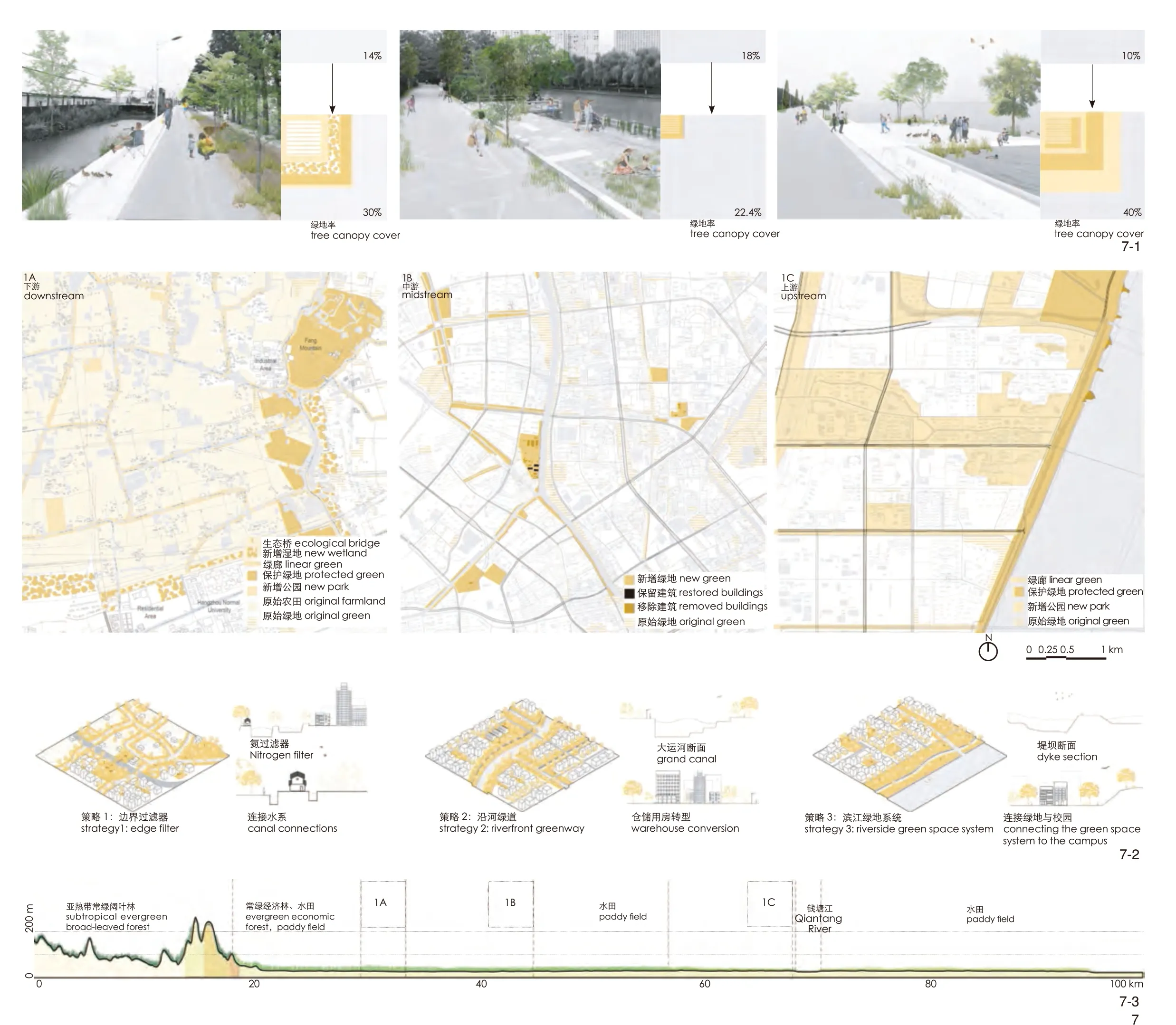

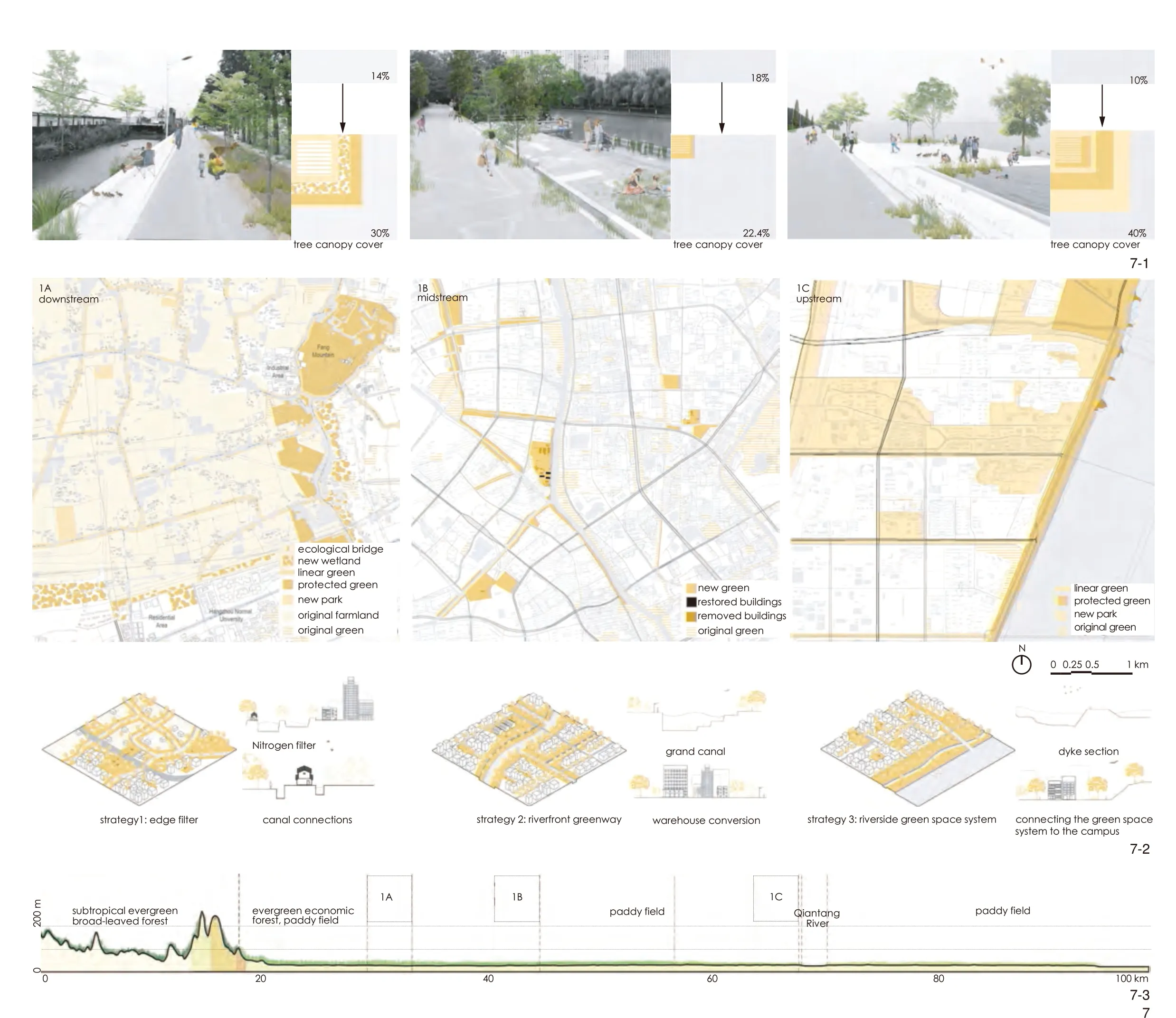

针对米兰3个4 km×4 km样本区域的生态景观策略包括绿道、绿巷和林地等不同种植设计方案。通过优化未利用碎片土地或大型交通基础设施附属用地,在每个样本区域增加10%以上的绿地,该策略响应了《米兰2030年总体规划》中计划种植300万棵树木的量化目标。杭州生态景观专题研究则采用“3-30-300”这一设计概念,即每户人家可见3棵树,每个街区30%的绿地率以及每个社区距最近的绿地300 m,来串联和提升生态空间,强化城市开发边界。针对杭州的3个样本区域,分别提出串联和过滤城乡边界、蓝绿交织的滨河空间以及串联滨江绿地系统的设计策略(图7)。

图7 针对杭州生态景观的“3-30-300”设计概念与策略The “3-30-300” design concept and related strategies for Hangzhou’s ecological landscape7-1 3个样本区域改造后效果和相应的绿地率变化Effects and corresponding changes in green space rate after renovation in three sample areas7-2 针对3个样本区域的设计概念、平面图和断面图Design concepts, plans, and cross-sections for three sample areas 7-3 杭州国土断面上的植被类型分布Distribution of vegetation types along Hangzhou’s territorial transect

5.3 生产性景观

米兰和杭州在成为大都市的一部分之前,均致力于生产食品和纺织品,以及开发自然资源。在诸如米兰市中心周围的传统农舍(意大利文:Cascine)以及杭州的采石场和老村庄中,这些传统生产方式的痕迹依然可见。

然而,生产性景观的概念在大都市的背景下具有了更广泛的含义。除了生产产品,一个高产的大都市景观还必须提供有助于大都市地区可持续发展的生态系统服务,特别是在雨洪管理、空气净化、生物多样性保护、提升文化认同和经济多样化等方面。从这个角度出发,考虑2个大都市农业的丰富性和历史重要性,我们探索了发展未来都市农业的潜力。

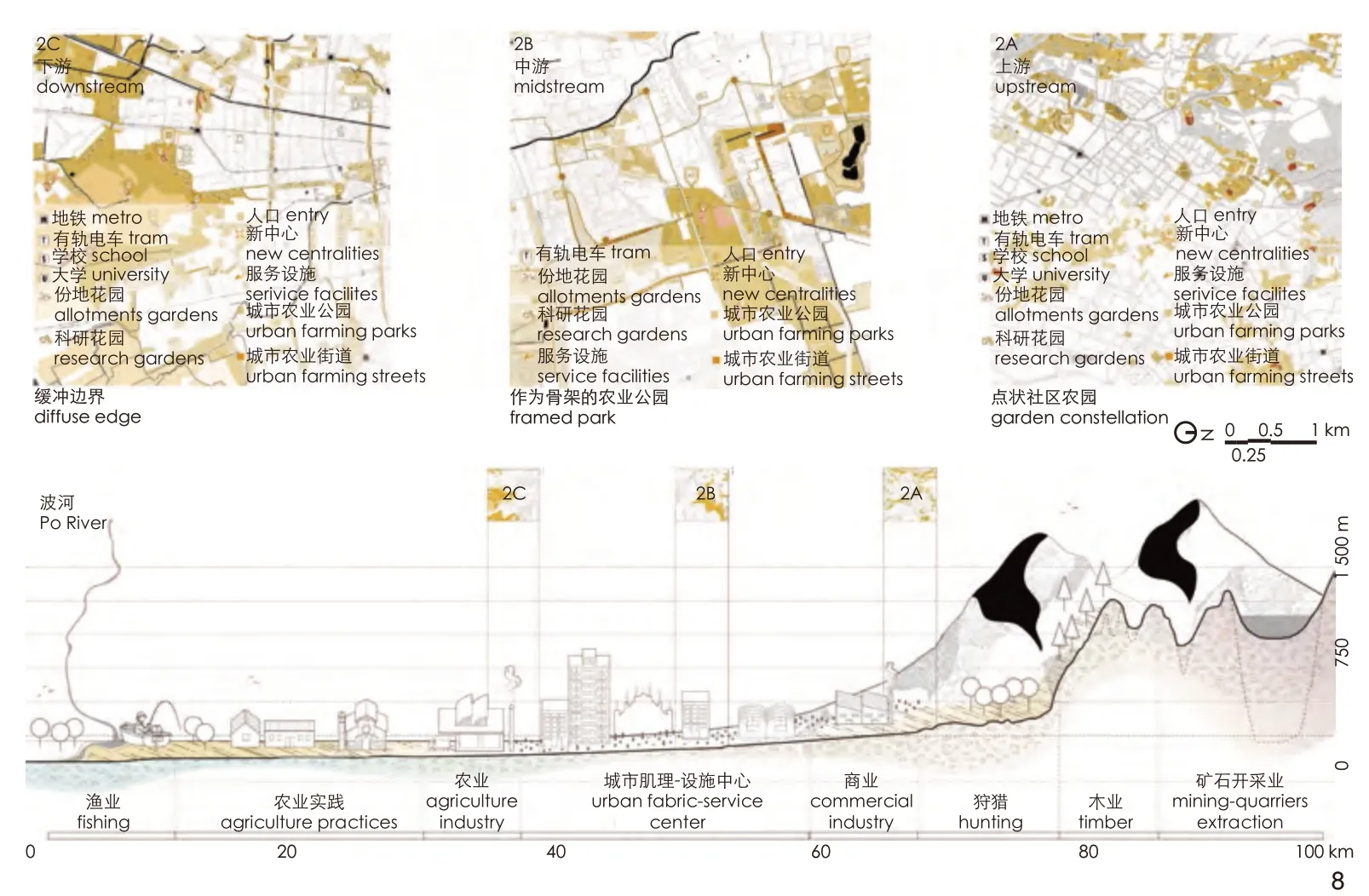

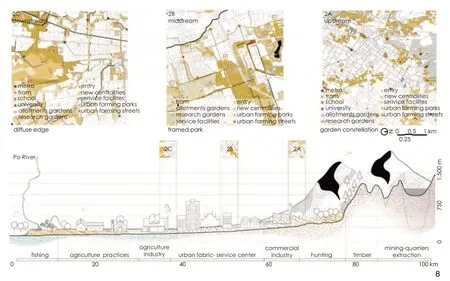

米兰生产性景观专题设计建议以社区农园的形式保留剩余的历史农业碎片,将它们串联成一个连续的系统,并尽可能增加农业用地,以实现《米兰 2030 年总体规划》提出的关于粮食安全的定量目标(图8)。针对杭州样本区域的设计策略则聚焦改造众多的平屋顶、社区周围未充分利用的装饰性或退界绿地及暂时闲置的地块,以建立临时城市农场。据估算,这些城市农场加起来可满足当地人口20%~30%的粮食需求。

图8 米兰国土断面的生产性景观初步设计Tentative design of Milan’s productive landscape shown with the transect

5.4 文化景观

大都市区域的规划面临的一个挑战,是作为一个包含多个城市的城市群,如何界定其中不同城市的特性,并提升这些城市文化景观的多样性[27]。媒体和官方旅游机构推动的城市文化认同倾向于关注历史城区的古迹。相比之下,国土断面方法在大都市的尺度上揭示了文化资源和名胜的多样性。

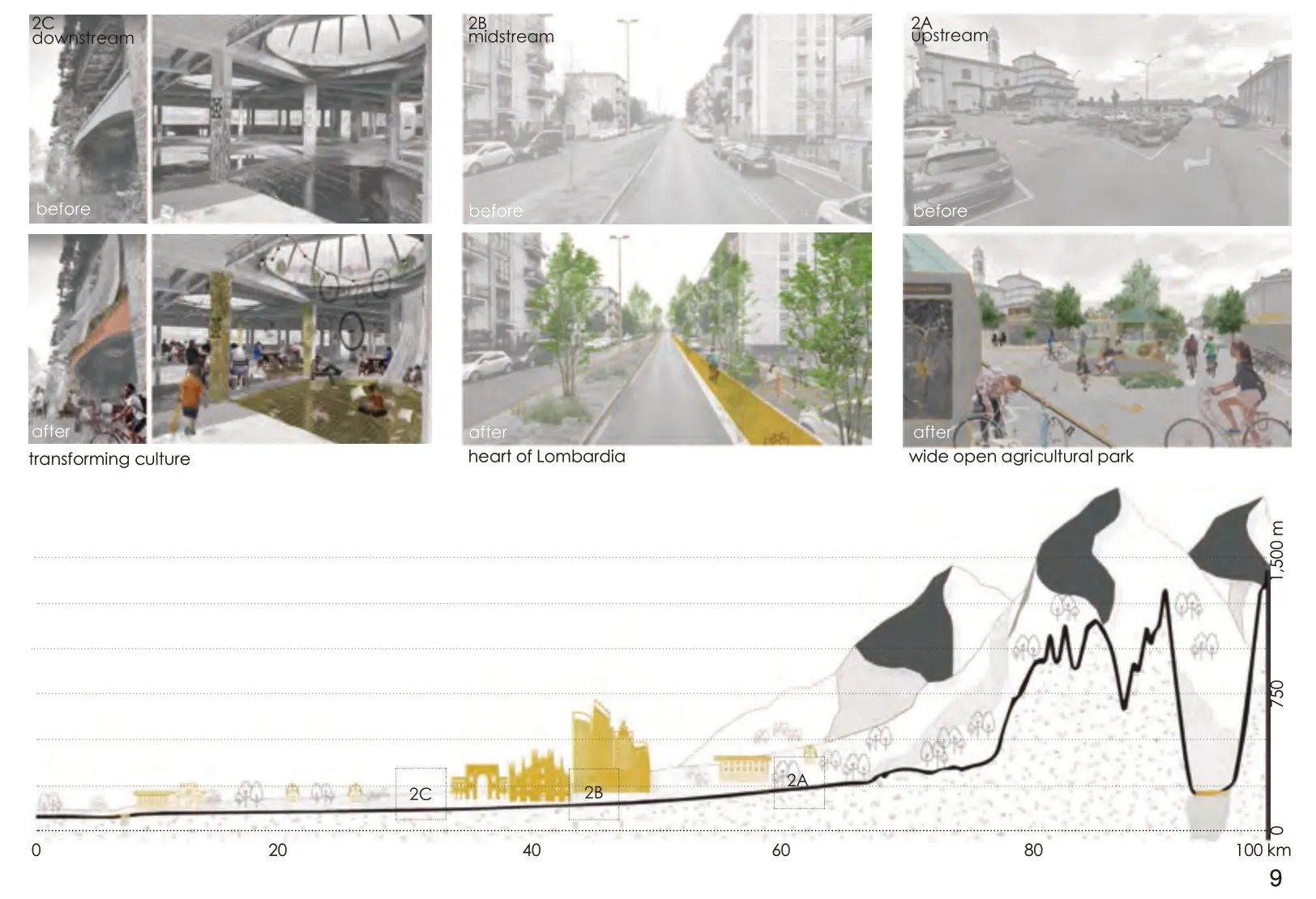

在米兰和杭州,古老的村庄、农场、后工业遗址和其他重要的名胜古迹在均质的城市环境中等待着被重新发现。一种可能的策略是通过统一的主题线路将它们连接起来。在米兰,沿着南北向的季节性河流或古老的纳维格里奥运河系统的一系列线路可将贯穿国土断面的历史城镇、村庄、老磨坊和传统农场串联起来(图9)。在杭州,文化景观与地形有着内在的联系:平原地区的日常景观由农业活动塑造,而丘陵地区则更多地与宗教景观联系在一起。杭州的文化景观专题设计根据国土断面起伏的地形,设想了3条主题线路,将地图上的兴趣点连接起来:山野线路将山间宗教文化建筑与山脚农业景观相连;运河线路将运河畔历史遗产建筑与日常生活设施相连;钱塘线路将江畔开放空间转变为城市滨江公园。

图9 沿着国土断面连接米兰文化景观的系列线路Design of a series of paths for linking Milan’s cultural landscapes along the transect

6 讨论:国土断面比较方法

除了针对米兰和杭州的具体研究结果以外,我们讨论了国土断面比较方法在其他大都市景观跨国研究中的潜力、限制和可推广的原则,主要包括3个重点。

6.1 保证可比性

第一个重点是使案例研究具有可比性。选择适宜的空间框架、尺度和具有代表性的样本区域是保障可比性的关键。1)相同的大尺度空间框架应考虑每个案例的自然地理特征和大都市尺度的行政区划。小尺度样本区域的选择必须能代表该地区景观特征的多样性。对于国土断面视图的选择,必须根据研究目标精准定位。例如在米兰和杭州的案例中,将断面与流域分布匹配后,有助于理解城市化与场地地形、土壤和贯穿其中的多个系统之间的关系。2)应用共享的图示语言至关重要。在城市形态学的研究传统中,分层系统和图底关系地图的使用使得复杂空间的比较成为可能。3)抽象化和陌生化②有助于对熟悉的环境产生新的见解,促使人们以不同的方式或更深入地看待它。

6.2 从历时性视角审视大都市景观

第二个重点是大都市景观是不断演变的动态现象而非静态蓝图[28]。对米兰和杭州的分析结果表明,它们当前的景观特征和环境条件是在一个特定的、长期的、复杂的历史地理过程中演变的结果。因此,针对特定大都市的挑战,我们必须考虑其景观的长时序轨迹,制定因地制宜的设计策略。

6.3 将国际信息与地方知识结合起来

第三个重点是用地方经验补充国际数据资源。全球地理信息系统数据、卫星图片和街景为在同一基础上比较偏远和先验的外国城市区域提供了极好的机会。然而,这些资源必然是有限的,并且在代表现实方面可能存在偏见。因此,为了保持批判性并避免简单化,建议将地方探索和场地的直接经验作为国际数据集的补充。

7 结论

大都市景观随处可见,但在不同地理和文化背景下,其景观特征的差异显著。尽管它们面临着诸如气候变化这样的共同挑战,但这些挑战无法用普适性的策略来解决。通过米兰和杭州的案例,本研究展示了国土断面比较方法如何通过2种互补的方式,更好地理解大都市景观的广博性、复杂性和多样性。

首先,2个大都市景观的比较结果揭示了其相似之处及可相互借鉴之处,并展现了每个大都市景观的独特性。就类比而言,这2个大都市景观在空间上均根植于它们的水文和农业系统,但目前均面临农业空间丧失和生态系统破碎等问题。机遇都在于激活剩余开放空间的生产功能,并认识到文化景观的多重特性。关于差异,这2个大都市景观面临着各自特有的挑战,这是它们在各自的地理、空间和社会文化背景下不断发展变化所导致的。因此,这一比较表明可以在解决共同问题方面相互学习,但更重要的是,强调了针对每种情况需要深入调查并量身定制设计策略。其次,从地理学和景观规划的悠久传统中继承下来的国土断面视图,挑战了城市规划的平面视图。这种平面视图倾向于将城市表现为特定行政边界内的中心辐射同心圆系统;而我们的大都市区断面视图则凸显了城市系统的不对称性,阐明了城市化与支持它的自然系统之间的基本关系。

致谢:

该工作室的研究和教学工作得到了Antonio Longo教授(米兰理工大学)、李咏华教授(浙江大学)、Sven Stremke副教授(瓦格宁根大学)、Wim Wambecq博士(鲁汶大学)、Bram Vandemoortel(根 特 大 学、Architecture Workroom Brussels事务所)、王志芳研究员(北京大学)、张斗设计总监 (sasaki)、王冬院长(土人景观)、Chiara Geroldi助理教授(米兰理工大学)、Andrea Palmioli助理教授(宁波诺丁汉大学)的参与和支持。同时也要感谢助教Raffaele Orrú以及米兰理工大学景观专业的35位学生和浙江大学风景园林、建筑、城乡规划专业的12名学生的参与。

注释:

① 例如,米兰大都市推动的ForestaMi项目,计划到2030年种植300万棵树(forestami.org/en/#);赫尔辛基大都市区的案例(详见参考文献[6][7])。

② 陌生化(defamiliarization or “ ostranenie”)是俄罗斯形式主义者维克多·什克洛夫斯基(Viktor Shklovsky)在1917年提出的一个术语,是一种以不熟悉或新的方式向人们呈现熟悉事物的技术。这样人们就能获得新的视角,以不同的方式看待世界。

图片来源:

图1由Christian Nolf改绘自von Humboldt(1841年)和Piero della Francesca(1465年);图2由Christian Nolf绘制;图3由米兰理工大学和浙江大学学生绘制;图4-1、5、6由Aya Toni、Carl Pauline、Deja Michal、Ganne Simon、Tomaszewska Patrycja绘制;图4-2由邹洁、朱恺芸、郑家诚绘制;图7由Marylu Barrett、Maria Stella Buoncompagno、Dafna Galeen、Seyedalireza Miraghaei、王艺霖绘制;图8由Maria Camila Katich Restrepo、Laura Cristina Parra Amariles、Luis Miguel Ocampo Marin、Erfan Rahbarzare绘 制;图9由Nicole Dietrich、Lea Fast、Celine Maissonave提供。

(编辑 / 王一兰)

作者简介:

(比利时)克里斯蒂安·诺尔夫 / 男 / 博士 / 瓦格宁根大学风景园林研究所讲师 / 研究方向为转型地区的城市发展、基础设施和景观之间的动态相互作用

(比利时)弗洛伦斯·范诺贝克 / 女 / 比利时BUUR Part of Sweco事务所鲁汶办公室空间研究所城市设计与规划师 /研究方向为城市更新中的城市生态、遗产保护和协作式规划

严诗忆 / 女 / 东南大学建筑学院在读硕士研究生 / 研究方向为城市蓝绿空间系统规划

谢雨婷 / 女 / 博士 / 浙江大学园林研究所讲师 / 研究方向为景观与区域规划

通信作者邮箱:xieyuting@zju.edu.cn

NOLF C, VANNOORBEECK F, YAN S Y, XIE Y T.Imagining Two Metropolitan Landscapes: A Comparative Territorial Transect Method for Milan and Hangzhou[J].Landscape Architecture, 2024, 31(1): 23-38.DOI: 10.3724/j.fjyl.202309150423.

Imagining Two Metropolitan Landscapes: A Comparative Territorial Transect Method for Milan and Hangzhou

(BEL) Christian Nolf, (BEL) Florence Vannoorbeeck, YAN Shiyi, XIE Yuting*

Abstract:[Objective] As urbanization continues to spread around the world, the notion of metropolitan landscape is increasingly relevant to describe the hybrid spatial character of large urbanized regions beyond the urban and rural categories.Furthermore, with future uncertainties stemming from climate change, the cross-comparison of metropolitan landscapes from different contexts helps identify common global environmental challenges and draws mutual lessons regarding adaptation and mitigation strategies.We aimed to verify the cross-comparison of the Milan and Hangzhou metropolitan regions through a comparable dual portrait at the metropolitan scale.[Methods] Therefore,we introduced the comparative transect method, rooted in physical geography and landscape planning, urban morphological analysis, and comparative studies, to investigate the two metropolitan landscapes.In each context, we began by framing the 100 km×100 km study areas with 100 km-long crosssectional transects at the XL scale, and sample areas of 4 km×4 km at the L scale.Four thematic layers of water, ecology, productive, and cultural landscape embedded in each sample area were examined from a synchronic and diachronic perspective to formulate context-sensitive design strategies.

[Results]The results compiled in a mirroring diptych reveal the analogies of landscape characteristics, trends, challenges, opportunities, and potential mutual learnings, and, by contrast, the uniqueness of each context.Furthermore, the transect view of both metropolitan areas illuminates the fundamental relationships between urbanization and the natural systems that support it.[Conclusion] The transect view challenges the plan view that is too often limited to administrative boundaries and implies the understanding of the city as a radio-concentric system.The comparative territorial transect method offers a systematic and critical reading of metropolitan landscapes, and its results contribute to the quantitative goals for green space and food security proposed in “Great Milan 2030” and the Hangzhou Territorial Spatial Planning 2021-2035.

Keywords:metropolitan landscape; landscape character; territorial transect;comparative study; research through design; territorial spatial planning

©BeijingLandscape ArchitectureJournal Periodical Office Co., Ltd.Published byLandscape ArchitectureJournal.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

1 What are Metropolitan Landscapes?

The term metropolitan landscape is not new.It has been mentioned since the 1970s in ecological studies to qualify the environmental problems of vast urbanized regions[1].Later, this term gradually acquired a more comprehensive meaning to describe the hybrid and dynamic spatial condition that characterizes many contemporary urbanized regions beyond the formal urban-rural categories.Observing it as a 21st-century urban phenomenon of the developed world, spatial planner Peter Bosselmann[2]defines metropolitan landscapes as a patchwork of insular development patterns with no clear structure.Furthermore, he explains its emergence as the unplanned and accidental outcome of forces of growth, decline, and waste.Witnessing the same phenomenon in Western Europe, Van den Brink et al.[3]see in metropolitan landscapes a call to reconsider the very meaning of landscape in contemporary urban regions.Landscape can no longer be understood as the open space counterpart of consolidated built-up spaces but as“the common denominator in an(inhabited) environment that combines built and unbuilt spaces under the influence of a metropolitan life”[3].As urbanization continues to spread around the world[4], the inclusive concept of metropolitan landscape might become increasingly relevant to describe the hybrid condition of urban regions and address the many environmental challenges these regions face.

2 Why Compare Metropolitan Landscapes?

Metropolitan landscapes from around the world are facing similar issues.Some issues derive from the effects of urbanization itself, including the loss of farmland and the pressure on natural resources like fresh water and air[3,5].Other issues derive from climate change and affect the fragile balance of the ecological environment in which urban regions have developed.To mitigate climaterelated flood risk, heat waves, and increasing water stress, many metropolitan cities are adopting ambitious plans for urban forestry, circular water systems, and renewable energy[6-7]①.

In this context of global climate urgency, the notion of metropolitan landscape is no longer limited to land use or morphological concerns.It is increasingly associated with infrastructural measures capable of maintaining good living conditions in all parts of urbanized regions.To this end, the cross-comparison of metropolitan landscapes from different contexts can offer insights into common environmental challenges and mutual lessons regarding adaptation and mitigation strategies.

The empirical comparison of cities has long been used in spatial research, including in urban morphology[8].Influential precedents likeThe Art of Building Citiesby Camillo Sitte[9]andGreat Streets

by Allan B.Jacobs[10]used the systematic comparative review of multiple cases to identify typologies or to derive universal principles.Other researchers use dual comparison to highlight contrasts between two models, such as Rowe and Koetter[11], who opposed the urban fabric of traditional and modernist cities inCollage City, or Kühn[12], who differentiated the green belt and green heart planning concepts.

For two decades, the development of multisource geospatial datasets, satellite pictures, and street views on a planetary scale has immensely facilitated the comparison of different contexts[13].Many comparative researchers use such international databases to assess the performance of urban design parameters[14]or to investigate the long-term interplay of urbanization and environmental challenges across regions[15-16].If international datasets represent an unparalleled resource for comparative studies, they must be used critically to avoid the risks of over-simplification and universalism that can derive from them.

3 Why Compare Milan and Hangzhou?

Milan and Hangzhou are among the most dynamic metropolitan areas in Europe and China.Separated by more than 9,000 km, Milan and Hangzhou nevertheless share some similarities.As prosperous economic centers between mountains and agricultural plains, the two cities developed rapidly to form large metropolitan areas[17-18].Home to 8 and 10 million inhabitants, respectively, the metropolitan regions of Milan and Hangzhou face pressing environmental and development challenges today.Issues of flooding and water scarcity, loss of biodiversity, and food security challenge the sustainability of the two urban regions and demand responses at the metropolitan scale[19-20].

In response, Milan and Hangzhou have recently embarked on ambitious territorial plans to reconcile their urbanization with the metropolitan landscape as an integral and structuring system.The territorial strategy “Great Milan 2030” and the associated vision of “Metropolitan Park”[21]echo the new development priorities of its Chinese counterpart.As a major city in the Yangtze River Delta, Hangzhou is revising its master plan in the Territorial Spatial Planning 2021−2035 according to the new priority of the national strategy“Ecological Civilization.” It can be seen as a vivid case illustrating the changing role of landscape in contemporary Chinese urban planning.

The comparison of Milan and Hangzhou metropolitan regions has two objectives: On the one hand, to identify potential analogies of landscape characteristics, trends, challenges, and opportunities in a perspective of mutual learning;on the other hand, to highlight the specificity of each context through a dual portrait.Developed in the frame of a transnational education project in landscape architecture and urban design, this comparative exercise has a didactic goal to encourage future spatial designers to develop a systematic and critical understanding of metropolitan landscapes.Furthermore, the results may also, after dissemination, be of interest to the decision-makers and planners of the two metropolitan regions.

4 How to Compare Metropolitan Landscapes?

Suppose metropolitan landscapes are, by definition, fuzzy and hard to delineate; then how to analyze and represent them becomes a tricky question.In response, Bosselmann[2]recalled the benefits of the territorial transect as a descriptive method.Developed in the 18th century by biogeographers like Alexander von Humboldt to monitor the spatial distribution of fauna and flora within a given area, the transect has since found many applications in other disciplines[22].In environmental planning theory, Patrick Geddes’s famous Valley Section[23]expressed the interdependency between cities and their situated regions through a transect.In landscape planning,Ian McHarg’s seminal bookDesign with Nature[24]employed transects to dissect the relationships between urbanization, physical geography, and ecosystems.More recently, in urban planning and design, New Urbanism — assuming a radioconcentric layout of the city — used the transect as a prescriptive model for visualizing the transition from urban to rural into six zones in decreasing density[25].Besides the cross-section view,Bosselmann[2]used the frames of 50 km×50 km,4 km×4 km, and 1 km×1 km and applied the layered figure-ground diagram techniques of morphological analysis to discern the layouts of water systems, blocks and streets, and the patterns of agriculture in the analysis of metropolitan regions.

Therefore, a territorial transect that combines views in cross-section and views in a plan at different scales could offer new techniques for interpreting and visualizing diverse landscape characteristics.While the cross-section depicts the links between urbanization and the physical geography features of a site, the views in a plan at different scales help decipher the spatial patterns distribution of systems and elements that make up the metropolitan landscape.In this design research project, we combine the traditions of the territorial transect, urban morphology, and comparative studies to compare the two metropolitan landscapes and imagine their future (Fig.1).The method consists of four main approaches.

4.1 Framing

First, we set up a frame that represents both study areas’ physical geography and includes the relevant administrative boundaries.For Milan and Hangzhou, a 100 km×100 km frame (at the XL scale of 1∶100,000) proved just correct to contain the Metropolitan City of Milan and the greater Hangzhou and, at the same time, embrace a significant part of their catchment, from the upstream mountains to the main river downstream(Fig.2).Within the XL square frame, a series of 100 km cross-sectional transects were traced from edge to edge.The purpose of using transects is to move away from the preconceived radio-concentric(center-periphery) representation of metropolitan regions in favor of its systematic analysis as an urbanized field with varying intensities.Along each transect, 3 sample areas of 4 km×4 km (at the L scale of 1∶5,000) were selected to investigate different zones in more detail, representing various landscape structures, patterns, urban fabrics, and densities.

4.2 Define Thematic Layers

Second, to facilitate the study of the metropolitan landscapes, we broke them into four thematic layers: water, ecology, productive, and cultural landscape.Each layer was investigated from a synchronic and diachronic perspective: the former perspective highlights the diverse spatial patterns found in the metropolitan region today;the latter perspective, based on the comparison of historical maps and satellite pictures, reveals the evolution of each layer.

4.3 Imagining Design Strategies

Based on each thematic layer’s spatial analysis and evolution, current challenges were identified,and a series of possible design strategies were imagined in response.

4.4 Comparing in a Mirroring Diptych

The last approach was to compare the two metropolitan landscapes.Two teams, located in Milan and Hangzhou, regularly exchanged to compare the spatial evolution, challenges, and possible design strategies for their respective contexts.Using the same open-source international database (OpenStreetMap and Google Earth) and applying the same spatial and thematic framework,the results were presented in a mirroring diptych and discussed during regular meetings.

5 Results

The exploration of each metropolitan landscape and their comparison bring similarities and distinctive points to light (Fig.3).

5.1 Water Landscape

Milan and Hangzhou have been shaped by water.This observation is evident in Hangzhou,which is still characterized by its famous West Lake, Grand Canal, Xixi Wetland, and the dense grid of waterways that also frame urban blocks and rural plots.Although invisible today, water in Milan has still determined the foundation and development of the city.The very name of Milan, derived from the Latin “Mediolanum” (middle of the land),refers to the intersection of the dry and wet plains where natural springs have attracted the earliest settlements and textile manufacturing activities.Milan has also been structured by three main torrent rivers and transverse canals (Italian:Navigli).Most of these waterways, however, have been channeled or partially covered today.

图1 The comparative territorial transect method for generating a mirroring diptych

图2 The same spatial framework, composed of a 100 km×100 km frame, three transects, and 9 sample areas, was defined to compare Milan and Hangzhou

The main water challenge for both Milan and Hangzhou is adapting their drainage systems to the effects of urbanization and climate change.To address this challenge, the Milan case proposes three distinct strategies for the three 4 km×4 km sample areas regarding the water processes along the catchment (Fig.4): slowing down the water flow in the upstream part to increase the infiltration; buffering stormwater runoff in central urban areas with designed bioretention swales; using the height difference in the downstream part to collect and filter run off to the urban boundary for agricultural irrigation before discharging into downstream rivers (Fig.5).Simultaneously, the open spaces around the water system are activated to make water more visible in the city (Fig.6).In the Hangzhou case, the mapping at the L scale shows pressing issues of channelization and poor connectivity in the water system.The study proposed three strategies respectively for the three sample areas: to use wetlands as buffer zones between built-up areas and rural areas; to restore some historical waterways to connect historical buildings with lakeside spaces; and to upgrade waterfront open space along agricultural ditches with recreational functions.These strategies will enable different water bodies of Hangzhou to play a structural role in future urban development (Fig.3).

5.2 Ecological Landscape

The ecological landscapes of Milan and Hangzhou present an asymmetrical profile (Fig.3).In Milan, the historical center is situated lower down, in between the relatively well-preserved agricultural wet plain downstream (Italian:Parco Agricolo Sud) and the dry plain where urbanization extends for tens of kilometers up to the Alp mountains.In Hangzhou, the historical center is located at the foot of the mountain, and urbanization spreads out in the alluvial plain downstream.In both cases, however, extensive urbanization replaced the pre-existing agricultural landscape and resulted in a fragmented ecological space[19,26].In response, there is a need today to restore the connectivity of ecological space at the regional scale, to contain further urban expansions,and to improve living conditions within the urbanized fabric.

图3 Overview of the territorial transects and thematic design strategies in each metropolitan context

In Milan, our strategy consists of three planting solutions for the three 4 km×4 km sites:greenways, green alleys, and woodlands.Taking advantage of underused fragmented land or oversized transport infrastructure, each study area could increase green space by more than 10%.This strategy responds contextually to the quantitative objectives of the “Great Milan 2030” to grow three million new trees.For Hangzhou’s ecological landscape, we adopted the design concept of “3-30-300” to connect and enhance the ecological space and strengthen the urban development boundary.Specifically, each household can see three trees; each block has a 30% tree canopy cover; and each community is 300 meters away from the nearest green space.Besides, respective design strategies were proposed for the three sample areas to connect and filter the urban-rural edge, interweave riverfront with greenways, and link the isolated green space of the Qiantang riverside area (Fig.7).

5.3 Productive Landscape

Before being urbanized as part of the metropolis, the hinterlands of Milan and Hangzhou were dedicated to producing food and textiles and exploiting natural resources.Traces of this productive past are still partially visible today in the form of quarries and old village centers in Hangzhou and the plot structure and traditional farmhouses (Italian:Cascine) around the center of Milan.

Nevertheless, today’s notion of a productive landscape has a broader meaning in a metropolitan context.More than generating products, a productive metropolitan landscape must provide ecosystem services that contribute to the sustainability of the metropolitan area, particularly for water management, air purification,preservation of biodiversity, cultural identity, and economic diversification.From this perspective,and considering agriculture’s richness and historical importance in both contexts, our strategies for Milan and Hangzhou explored the potential of urban farming.

图4 Comparative mapping of the water systems of Milan and Hangzhou at the XL scale

图5 Three strategies for Milan’s water system: supply, buffer,filter

图6 Design strategies for Milan’s water system from upstream, midstream to downstream6-1 Design plans and cross-sections for three sample areas’ water systems6-2 Before and after renovation: water storage and filtration collectors in the upstream, streets’ bioretention swales in the midstream, and constructed wetlands along the urban boundary in the downstream

图7 The “3-30-300” design concept and related strategies for Hangzhou’s ecological landscape7-1 Effects and corresponding changes in green space rate after renovation in three sample areas7-2 Design concepts, plans, and cross-sections for three sample areas7-3 Distribution of vegetation types along Hangzhou’s territorial transect

In Milan, we proposed to preserve remaining historical agricultural pockets in the form of community agricultural parks, interconnect them into a green infrastructure system, and increase agricultural land to achieve the targets on food security of the Milan 2030 plan (Fig.8).In Hangzhou, the proposed strategy is to optimize the numerous flat roofs, underutilized ornamental and technical green spaces around communities, and plots under transforming to establish temporary urban farms.It has been estimated that these urban farms together could potentially contribute 20% to 30% of the food demands of the local population.

5.4 Cultural Landscape

A challenge for the planning of metropolitan regions is to recognize it as “a city of cities” and to strengthen its cultural landscape diversity[27].The cultural identity of urban regions promoted by media and official tourism agencies tends to focus on monuments in the city’s historical heart.The transect approach, in contrast, brings to light the rich diversity of cultural resources and places of interest at the scale of the metropolis.

In both Milan and Hangzhou, some old villages, farms, post-industrial sites, and other significant places of interest have been anonymized in the generic urban carpet and wait to be rediscovered.A possible strategy is to interconnect them through meaningful and unifying thematic routes.In Milan, a series of paths that follow the torrents or the old transversal canals have the potential to link the constellation of historic towns,villages, old mills, and traditional farms from the mountain to the agricultural park across the very urban center (Fig.9).In Hangzhou, the cultural landscape is intrinsically linked to topography.The low plains are reserved for everyday landscapes shaped by agricultural activities while higher grounds are associated with sacred religious landscapes with mountains as background.The group imagined three thematic itineraries interconnecting these places of interest, guided visually by the hills’ profile emerging from the horizon.The mountain route connects religious buildings in the mountains with agricultural landscapes at the foot of the mountains.Besides,the canal route connects heritage buildings along the Grand Canal with public facilities.Lastly, the Qiantang route transforms open spaces along the Qiantang River into riverside urban parks.

6 Discussion: Towards a Comparative Territorial Transect Method

In addition to the specific results for Milan and Hangzhou, it is interesting to discuss the potential, constraints, and generalizable principles of the comparative territorial transect method for the transnational study of any metropolitan landscape.Three highlights were discussed.

6.1 Ensure Comparability

The first highlight is to make the case studies comparable.Choosing the appropriate spatial framing, scaling, and graphic representation mode is essential in meeting this challenge.1) The same large-scale spatial frame should account for each case’s physical geography and metropolitan-scale administrative entity.The sampling of zoom areas must represent the diversity of landscape character.As for the transect views in the cross-section,they must be positioned purposely.When aligned with the watershed, as in the study of Milan and Hangzhou, the transect helps understand urbanization in relationship to the site’s topography, soil, and the multiple systems that run through it.2) The application of shared graphic coding is crucial.In the tradition of urban morphology, the use of layered systems and figure-ground diagrams facilitates the comparison of complex spaces.3) Abstraction and defamiliarization②contribute to generating a new view of a familiar environment, inviting people to see it differently or more deeply.

图8 Tentative design of Milan’s productive landscape shown with the transect

图9 Design of a series of paths for linking Milan’s cultural landscapes along the transect

6.2 Look at Metropolitan Landscapes from a Historical Evolutionary Perspective

A second highlight is not to approach metropolitan landscapes as static blueprints but as dynamic phenomena in constant evolution[28].The analysis of Milan and Hangzhou above illustrates how their current landscape characteristics and environmental conditions result from a specific,long, and complex historical-geographical process.To respond contextually to the challenges of metropolitan landscapes, strategies must be informed by their long-term trajectories.

6.3 Combine International Information with Local Knowledge

A third highlight is to complement international data resources with local insights.Global GIS data, satellite pictures, and street views offer an excellent opportunity to compare remote and a priori foreign urban regions on the same basis.However, these resources are necessarily limited and potentially biased in their representation of reality.In order to maintain a critical approach and avoid simplification, it is therefore recommended to complement the use of international datasets with local knowledge grounded in the exploration and direct experience of local sites.

7 Conclusion

Metropolitan landscapes are emerging everywhere, but their character differs significantly between geographies and cultures.Although they face common challenges — including those resulting from climate change, they cannot be addressed with universal solutions.Through the examples of Milan and Hangzhou, this paper shows how the comparative territorial transect method helps better understand metropolitan landscapes in their vastness, complexity, and diversity in two complementary ways.

First, comparing two metropolitan landscapes reveals analogies, potential mutual learnings, and,by contrast, the uniqueness of each context.In terms of analogies, the two metropolitan landscapes are spatially rooted in their hydrological and agricultural systems.Their current conditions are characterized by a loss of agricultural spaces and fragmentation of ecosystems.Opportunities lie in activating residual open spaces for productive functions and recognizing the multiple identities of their cultural landscapes.Regarding differences, the two metropolitan landscapes face specific challenges resulting from the distinct ways typical dynamics have taken shape in their own geographic, spatial,and sociocultural context.Hence, the comparison suggests possible mutual learning for addressing common issues but mainly highlights, by contrast,the need for in-depth investigation and tailored strategies for each context.Second, the transect view, inherited from a long tradition in geography and landscape planning, challenges the plan view of urban planning that tends to represent cities as radio-concentric systems within administrative boundaries.The transect view of both metropolitan areas highlights the asymmetry of the urban systems with an illustration of the fundamental relationships between urbanization and the natural systems that support it.

Acknowledgements:

This studio work benefited from the research and teaching support from Prof.Dr.Antonio Longo (Polytechnic University of Milan), Prof.Dr.Li Yonghua (Zhejiang University), Dr.Sven Stremke (Wageningen University), Dr.Wim Wambecq (KU Leuven; Atelier Midi), Bram Vandemoortel (Ghent University; Architecture Workroom Brussels), Prof.Dr.Wang Zhifang (Peking University),Zhang Dou (Sasaki), Wang Dong (Turenscape), Dr.Chiara Geroldi (Polytechnic University of Milan), Dr.Andrea Palmioli (University of Nottingham Ningbo China).Thanks also to the teaching assistant Raffaele Orrú and 35 landscape students from the Polytechnic University of Milan, as well as 12 students from Landscape Architecture,Architecture, and Urban and Rural Planning from Zhejiang University for their participation.

Notes:

① See, for instance, the project ForestaMi campaign promoted by the Metropolitan City of Milan to plant three million trees by 2030 (forestami.org/en/#) or the case of the Helsinki metropolitan area (see reference [6][7]).

② Defamiliarization or “ostranenie,” a term coined in 1917 by Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, is a technique of presenting people with familiar things in an unfamiliar or new way so they can gain new perspectives and see the world differently.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.1 © Christian Nolf, adapted from von Humboldt (1841)and Piero della Francesca (1465); Fig.2 © Christian Nolf;Fig.3 © participants from the Polytechnic University of Milan and Zhejiang University; Fig.4-1, 5, 6 ©Aya Toni,Carl Pauline, Deja Michal, Ganne Simon, Tomaszewska Patrycja; Fig.4-2 ©Zou Jie, Zhu Kaiyun, Zheng Jiacheng;Fig.7 © Marylu Barrett, Maria Stella Buoncompagno,Dafna Galeen, Seyedalireza Miraghaei, Wang Yilin; Fig.8 ©Maria Camila Katich Restrepo, Laura Cristina Parra Amariles, Luis Miguel Ocampo Marin, and Erfan Rahbarzare; Fig.9 ©Nicole Dietrich, Lea Fast, and Celine Maissonave.