Pancreatic cystic neoplasms:a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management

Amir M.Prry,Anoop Singh,Vikrm Chudhri,Avinsh Supe

Abstract Pancreatic cystic neoplasms present a complex diagnostic scenario encompassing low-and high-grade malignancies.Their prevalence varies widely,notably increasing with age,reaching 75%in individuals older than 80 years.Accurate diagnosis is crucial,as errors occur in approximately one-third of resected cysts discovered incidentally.Various imaging modalities such as computed tomography,magnetic resonance imaging,and endoscopic techniques are available to address this challenge.However,risk stratification remains problematic,with guideline inconsistencies and diagnostic accuracy varying according to cyst type.This review proposed a stepwise management approach,considering patient factors,imaging results,and specific features.This patient-centered model offers a structured framework for optimizing the care of individuals with pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

Keywords:Pancreatic cystic neoplasms;Cystic fluid analysis;Serous cystic neoplasm;Mucinous cystic neoplasm;Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm;Cystic tumors

1.Introduction

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) represent a paradoxical state akin to Schrödinger's box, simultaneously holding the potential for low-and high-grade malignancies until the surgeon unveils the truth within the patient's abdomen.[1]The prevalence of pancreatic cysts(PCs)reaches 50%;75%in those older than 80 years.[2-4]Although most PCs remain indolent,a small proportion of these provide an opportunity to prevent or cure pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma(PDAC).Expert consensus guidelines have been formulated to aid clinicians in using the dynamic predictors of malignant progression. Preoperative diagnoses are inaccurate in approximately one-third of incidentally detected cysts in patients undergoing excision; precise diagnosis of malignancy can thus prevent diagnostic errors.[5,6]Consequently,a range of invasive and noninvasive imaging modalities are available, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), contrastenhanced ultrasonography,and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration(EUS-FNA).This review aimed to present the current knowledge on the prevalence based on recent studies,morphological features of PCs,their correlation with estimated malignancy risk,available diagnostic tools to minimize clinically significant diagnostic errors,and patient-centered management.

2.Prevalence of PCNs

The prevalence of incidental PCs varies considerably(2%-75%),as demonstrated by large population-based studies conducted by Chang et al.,[7]Kromrey et al.,[8]and Schweber et al.[9]These studies highlight that the variations in prevalence can be attributed to differences in methodology, imaging modalities used, and inclusion criteria used.The finding that the prevalence of PCs increases with age is particularly remarkable, with a reported incidence of 75%among individuals older than 80 years,predominantly comprising intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms(IPMNs).Unfortunately,available data regarding the global distribution of PC burden are limited.However,a meta-analysis has suggested that the Asian population may have a higher incidence of asymptomatic PCs.[10]Age is a significant factor,as the prevalence of PCs increases with age.A comprehensive review found incidental PCs in 2.5%of individuals undergoing CT,with a 10%increase among those 70 years or older.Symptomatic PCs have a 2%to 38%prevalence according to MRI studies.[3,4,7-10]As the population ages, the incidental detection of these cysts is expected to increase,thereby posing challenges for clinicians,patients,and health care systems to manage effectively.

3.Classification of PCNs

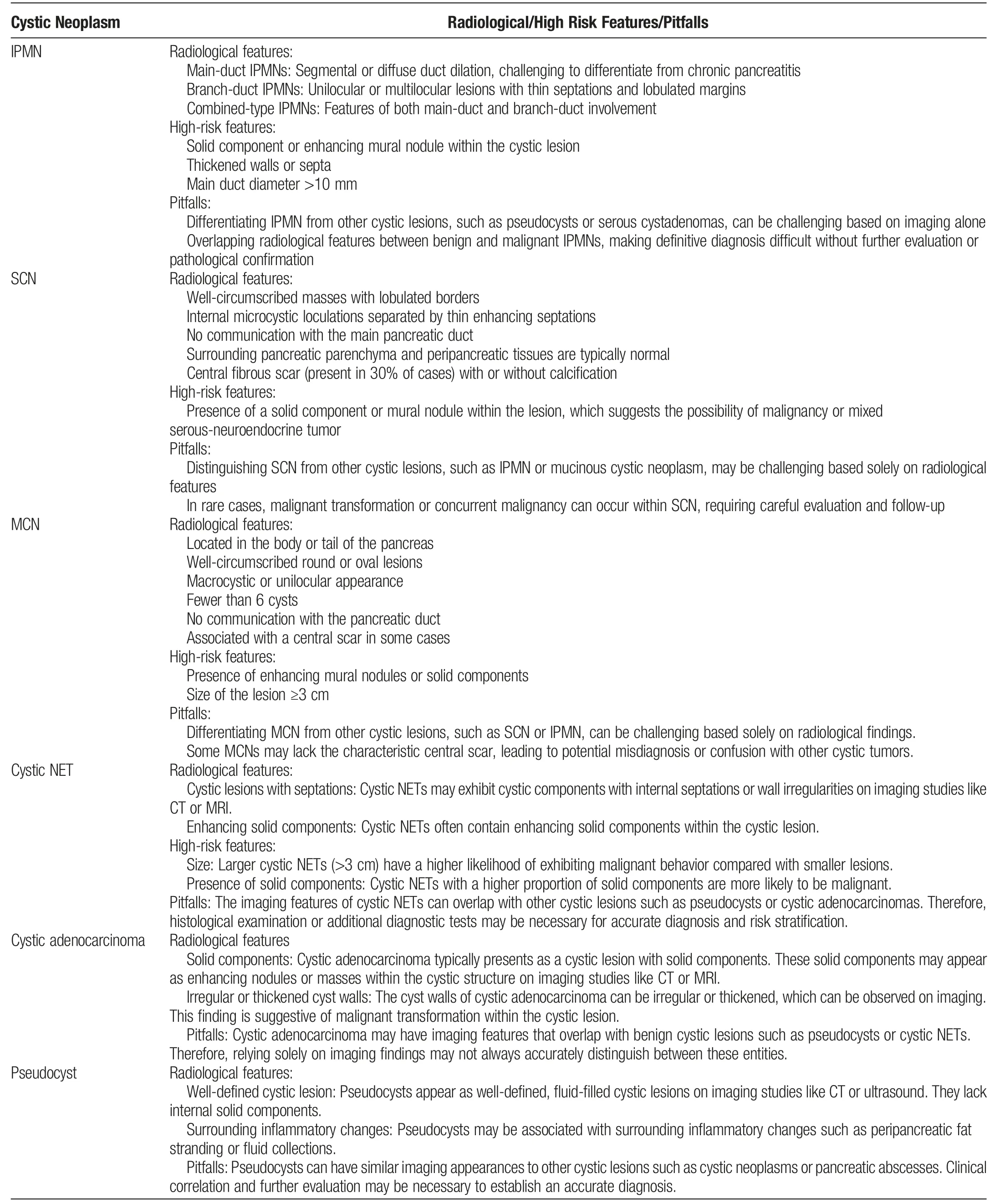

PCNs are a group of diverse lesions that can be classified into different categories based on their characteristics and malignant potentials(Table 1).[11-22]

Table 1Features of various PCNs

3.1.Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

Main-duct IPMNs (MD-IPMNs) account for 15% to 21% of IPMNs and present as segmental or diffuse dilatation of the Wirsung duct without any other cause of obstruction.They are mostly locatedin the cephalic(head)region of the pancreas and have the highest risk of developing malignant features(reaching approximately 81%).Surgical treatment such as pancreaticoduodenectomy(Whipple's procedure)is recommended for MD-IPMNs.[11-14]

Branch-duct IPMNs (BD-IPMNs) represent 41% to 64% of IPMNs and are characterized by round cystic lesions that communicate with the pancreatic duct.They are often small cysts (5-20 mm)with a grape-like appearance and are commonly found in the pancreatic head. Conservative treatment is the “gold standard“ for BD-IPMNs, considering factors such as multifocality, postsurgical recurrence rate, and lower risk of malignant progression. Surgical treatment is reserved for cases with absolute indications.[12,13]

Mixed-type IPMNs(MT-IPMNs)exhibit features of both MDand BD-IPMNs and have a higher risk of malignant progression(20%-65%).The treatment approach for MT-IPMNs is similar to that for MD-IPMNs.[11-14]

3.2.Mucinous cystic neoplasms

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) are typically asymptomatic and occur most frequently in the distal pancreas(body or tail).They are solitary cystic lesions with septa, often unilocular, and do not communicate with the pancreatic duct.MCNs can be differentiated from other cystic neoplasms, such as serous cystic neoplasms(SCNs) and IPMNs, based on imaging features and fluid analysis.Surgical resection is recommended for MCNs >3 cm,enhancing mural nodules,or symptomatic cysts.Lesions <3 cm follow the guidelines for IPMNs.[11,12,15,16]

3.3.Serous cystic neoplasms

SCNs are mostly asymptomatic and found in approximately 62-year-old individuals.They occasionally appear as multicystic lesions with a central scar or sunburst calcifications. Microcystic SCNs have a“honeycomb”appearance on endoscopic ultrasound(EUS). SCNs are usually benign; therefore, nonsurgical management with imaging surveillance is the preferred approach. Lesions with rapid growth or symptoms may require surgery.[11,12,15,17]

3.4.Cystic neuroendocrine tumors

Cystic neuroendocrine tumors are rare and nonfunctional tumors,often solitary and localized in the neck,body,or tail of the pancreas.They have a heterogeneous composition and can be evaluated using CT, MRI, and EUS. Surgical resection is recommended for cystic neuroendocrine tumors >2 cm, whereas surveillance is recommended for smaller and indolent tumors.[11,12,18-20]

3.5.Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms are rare tumors that occur primarily in young women and are localized to the distal pancreas.They have a heterogeneous appearance and contain solid and fluid components.EUS-FNA can aid in the diagnosis,and surgical resection is the treatment of choice,aiming for complete resection of the tumor and synchronous or interval metastasis,if possible.[11,12,21]

3.6.Acinar cell cystadenoma and carcinoma

Acinar cell cystadenomas are rare, slow-growing, benign cystic lesions.They can arise in any segment of the pancreas and are often isolated. Surgical resection is preferred, particularly for symptomatic tumors,because of the difficulties in identifying symptomatic tumors from acinar cell cystadenocarcinomas.Acinar cell carcinomas are rare, aggressive, and malignant tumors. They require surgical resectionof thelocalizedtumor;insomecases,synchronousandmetachronous liver resection may be performed for metastatic disease.[22]

3.7.Other rare pancreatic cystic lesions

Other rare PCNs include ductal adenocarcinomas with cystic degeneration, cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts), intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms,and osteoclast-like giant cell tumors.These lesions exhibit distinct characteristics, imaging features, and treatment approaches.

4.Risk estimation

Multiple societal guidelines and subpar imaging modalities render PCN risk stratification ineffective.[23-34]With advances in crosssectional imaging,recent retrospective studies have reported an accuracy of approximately 80%for CT and MRI,compared with that of 39%to 45%reported in previous studies.[23]Because of the overlapping morphologies of atypical cystic neoplasms and BD-IPMNs,SCNs exhibit an approximately 60% lower diagnostic accuracy.[24,25]In a large multicenter study of SCNs,61%of 2622 patients underwent surgery,with an uncertain diagnosis as the surgical indication in 60% of patients.[26]In addition, the accuracy of risk stratification was lower in patients with BD-IPMN.The surgical series overestimates malignancy risk, whereas the surveillance series underestimates it.A multicenter follow-up study of 292 patients under surveillance who underwent surgery because of worrisome features or high-risk stigmata highlighted the need for diagnostic accuracy. This study involving highly specialized centers found no high-grade dysplasia or malignancy on final histopathology in 63%of patients.[27]

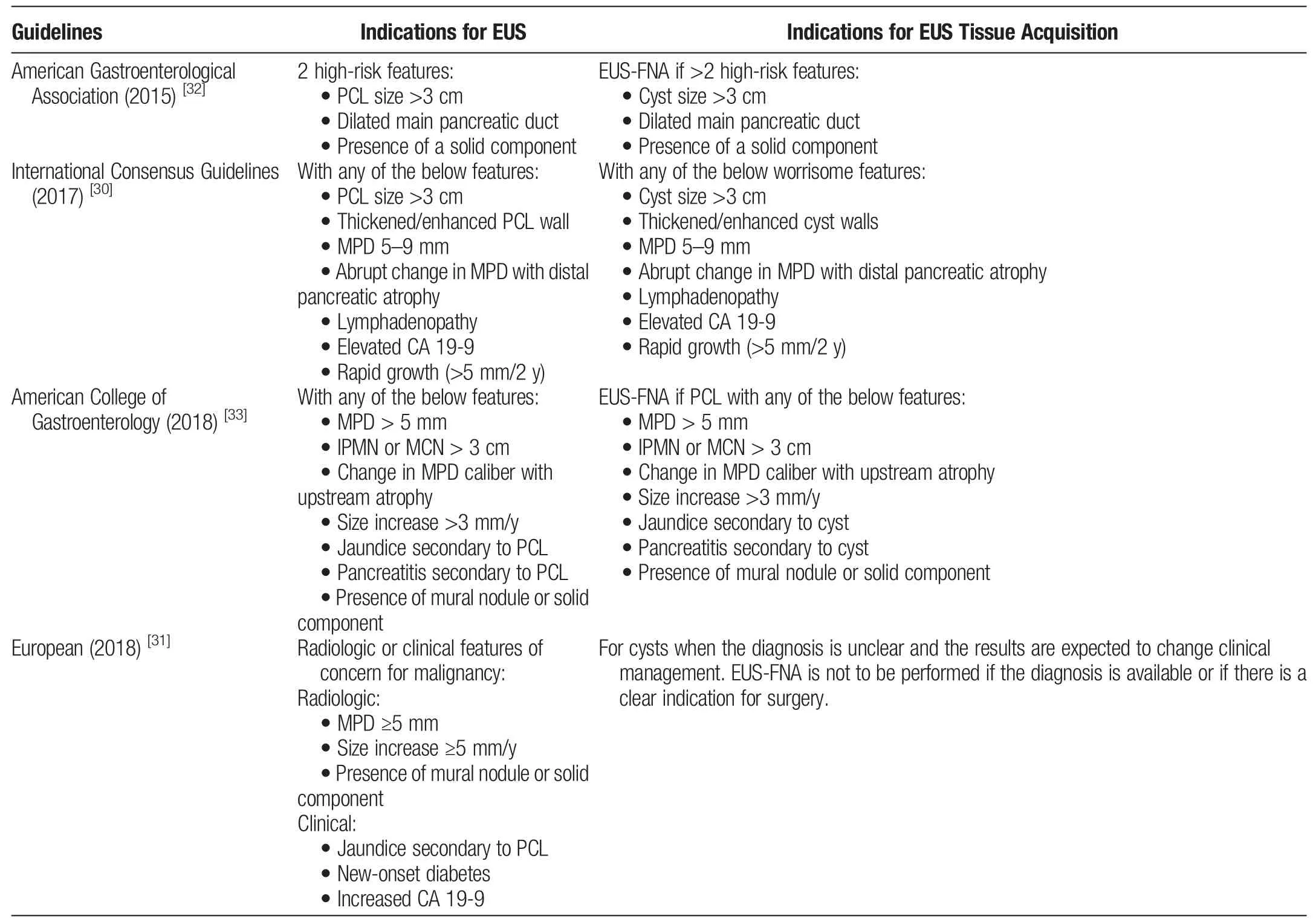

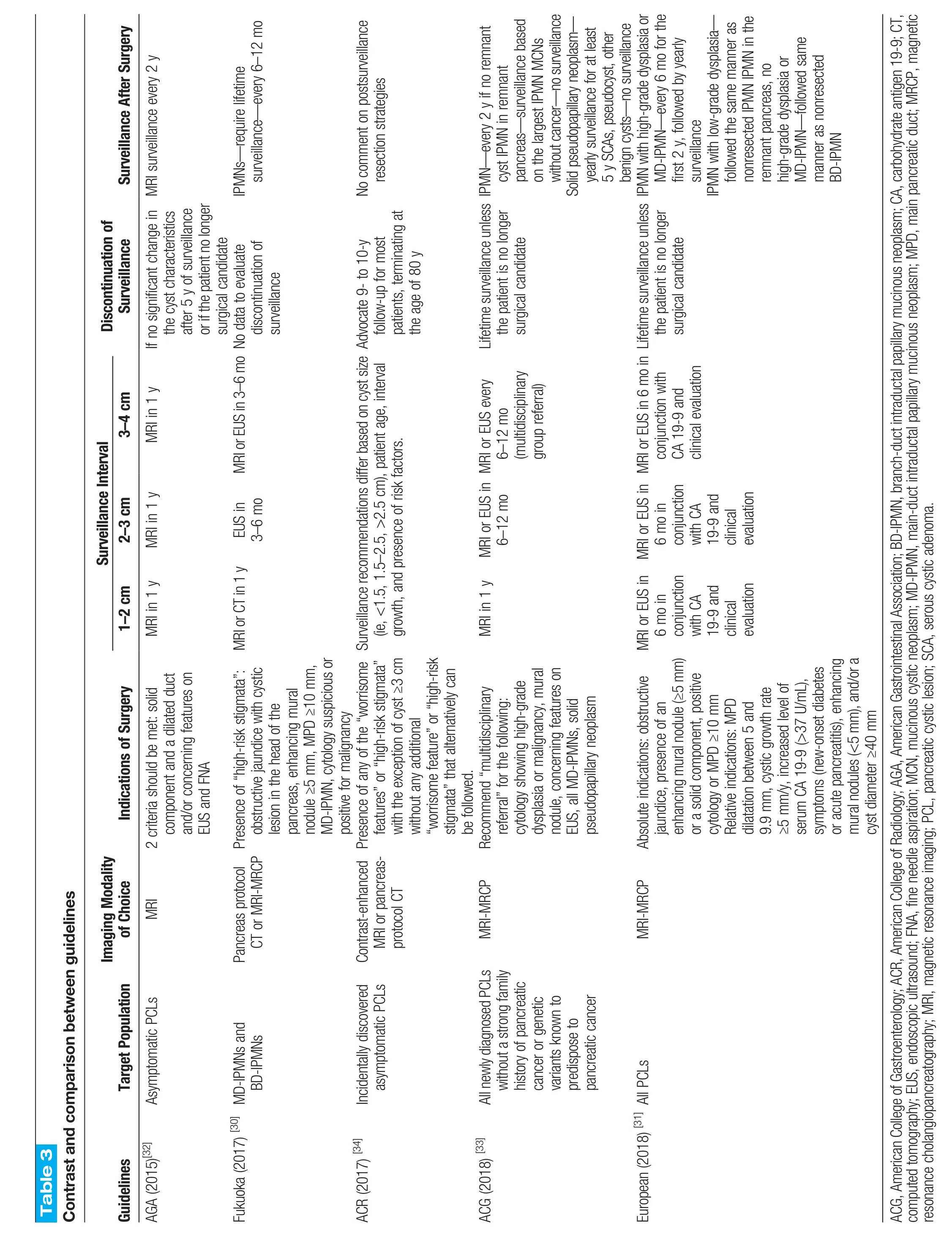

There are subtle variations in terms of intended audiences,target cyst types,and surveillance and management recommendations in 5 major societal guidelines:the American Gastrointestinal Association(AGA) guidelines, American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)guidelines, American College of Radiology (ACR) recommendations, European evidence-based guidelines, and International Association of Pancreatology (IAP)/Fukuoka guidelines.[28-34]The European guidelines for the management of pancreatic cystic lesions introduced unique aspects of their risk assessment approach.Notably,they considered the development of new-onset diabetes as an indication for potential surgery. Another notable aspect of these guidelines is the use of a 4-cm cyst size threshold as a potential indication for surgery,which is larger than the 3-cm threshold found in many other guidelines.However,most other guidelines typically use a 3-cm size criterion when deciding on surgery or further evaluation,highlighting a difference in the size parameter for assessing risk.Regarding the management of MCNs, the European Guidelines recommend surgical intervention for MCNs that measure ≥40 mm or exhibit associated risk factors.However,these guidelines do not offer clear recommendations for MCNs within 3 to 4 cm.Conversely,other guidelines,such as the AGA and IAP guidelines,do not specifically distinguish MCNs but instead concentrate on factors such as cyst size, solid components, and the extent of dilation in the main pancreatic duct as risk indicators. The ACR guidelines considered age in their risk assessment approach.This age-dependent strategy differs from most others,which assess risk based on cyst characteristics and clinical factors without explicitly considering age.The IAP guidelines classify cysts into“high-risk,”“worrisome features,”and“low-risk” categories based on factors including obstructive jaundice,cyst size,mural nodules,and carbohydrate antigen(CA)19-9 levels.This detailed approach offers a comprehensive risk-assessment strategy.In contrast,the AGA guidelines emphasize high-risk features and recommend further evaluation of patients with 2 or more of these characteristics.Although they do not directly recommend surgery,they emphasize the significance of specific risk factors in the decision-making process[28-34](Table 2).

Table 2Indications of EUS and EUS FNAC

The accuracy of these guidelines reportedly ranges 45%to 75%across different studies.[35,36]The diagnostic performance of these guidelines is poor,with an area under the curve of 0.53,which needs to be considered in conjunction with the postpancreatectomy major morbidity rates of up to 40%[37](Table 3).

5.Imaging of PCNs

5.1.Cross-sectional imaging

Cross-sectional imaging helps stratify malignancy risk of pancreatic cystic lesions, in addition to important aspects such as its location within the pancreas,size,morphology or shape,the presence of enhancing nodules or septa,and its relationship to the main pancreatic duct. In addition, the size and morphology of the main pancreatic duct should be examined along with an assessment of the surrounding uninvolved pancreatic parenchymal and peripancreatic tissues.[22-24]

MRI and multidetector CT,which are equally effective,are used to diagnose pancreatic cystic lesions. MRI has several advantages,including enhanced lesion characterization and no ionizing radiation.[38,39]Thus, guidelines recommend using MRI/MRCP with gadolinium-based intravenous contrast agents for surveilling such lesions. Enhancing mural nodules >5 mm and cyst-wall enhancement are crucial indicators for the risk stratification of IPMNs.In low-risk populations,noncontrast MRI/MRCP demonstrates similar management decisions to contrast-enhanced imaging according to retrospective studies.[22,23]Because of its wide availability and high spatial resolution, contrast-enhanced CT is commonly used in preoperative planning.CT or MRI can show vascular architecture, metastases, and abdominopelvic involvement. The choice between MRI and CT depends on local institutional practices and surgeon preferences.Because of its subjectivity and inadequate visibility, transabdominal ultrasonography has limitations in PC evaluation.Tables 1 and 3 show the radiological features and risk stratification of the different PCNs.[22-24,38,39]

5.2.Endoscopic ultrasound

EUS with or without fine needle aspiration (FNA) provides highresolution images for cyst size, septations, calcifications, nodules,and main pancreatic duct (MPD) diameter measurement. EUS is useful when the radiological diagnosis of malignancy is inconclusive or when cysts show clinical or radiological features.40-44

Table 3 Contrast and comparison between guidelines Surveillance After Surgery MRl surveillance every 2 y lPMNs—require lifetime surveillance—every 6–12 mo No comment on postsurveillance resection strategies every 2 y if no remnant cyst lPMN in remnant lPMN—pancreas—surveillance based on the largest lPMN MCNs without cancer—no surveillance Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm—yearly surveillance for at least 5 y SCAs,pseudocyst,other benign cysts—no surveillance lPMN with high-grade dysplasia or MD-lPMN—every 6 mo for the first 2 y,followed by yearly surveillance lPMN with low-grade dysplasia—followed the same manner as nonresected lPMN lPMN in the remnant pancreas,no high-grade dysplasia or MD-lPMN—followed same manner as nonresected BD-lPMN Discontinuation of Surveillance lf no significant change in the cyst characteristics after 5 y of surveillance or if the patient no longer surgical candidate discontinuation of surveillance Advocate 9-to 10-y follow-up for most patients,terminating at the age of 80 y Lifetime surveillance unless the patient is no longer surgical candidate Lifetime surveillance unless the patient is no longer surgical candidate Surveillance Interval 3-4 cm MRl in 1 y MRl or EUS in 3–6 mo No data to evaluate MRl or EUS every 6–12 mo(multidisciplinary group referral)MRl or EUS in 6 mo in conjunction with CA 19-9 and clinical evaluation 2-3 cm MRl in 1 y EUS in 3–6 mo MRl or EUS in 6 mo in conjunction with CA 19-9 and clinical evaluation 1-2 cm MRl in 1 y MRl or CT in 1 y Surveillance recommendations differ based on cyst size(ie,<1.5,1.5–2.5,>2.5 cm),patient age,interval growth,and presence of risk factors.MRl in 1 y MRl or EUS in 6–12 mo MRl or EUS in 6 mo in conjunction with CA 19-9 and clinical evaluation Indications of Surgery component and a dilated duct and/or concerning features on EUS and FNA obstructive jaundice with cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas,enhancing mural nodule ≥5 mm,MPD ≥10 mm,MD-lPMN,cytology suspicious or positive for malignancy features”or“high-risk stigmata”with the exception of cyst ≥3 cm without any additional“worrisome feature”or“high-risk stigmata”that alternatively can be followed.cytology showing high-grade dysplasia or malignancy,mural nodule,concerning features on EUS,all MD-lPMNs,solid pseudopapillary neoplasm jaundice,presence of an enhancing mural nodule(≥5 mm)or a solid component,positive cytology or MPD ≥10 mm Relative indications:MPD dilatation between 5 and 9.9 mm,cystic growth rate≥5 mm/y,increased level of serum CA 19-9(>37 U/mL),symptoms(new-onset diabetes or acute pancreatitis),enhancing mural nodules(<5 mm),and/or a cyst diameter ≥40 mm Target Population Imaging Modality of Choice 2 criteria should be met:solid Presence of“high-risk stigmata”:Presence of any of the“worrisome Recommend“multidisciplinary referral”for the following:Absolute indications:obstructive MRl Pancreas protocol CT or MRl-MRCP Contrast-enhanced MRl or pancreasprotocol CT MRl-MRCP MRl-MRCP lncidentally discovered AGA(2015)[32]Asymptomatic PCLs Fukuoka(2017) [30] MD-lPMNs and BD-lPMNs asymptomatic PCLs All newly diagnosed PCLs without a strong family history of pancreatic cancer or genetic variants known to predispose to pancreatic cancer Guidelines ACR(2017) [34]ACG(2018) [33]European(2018) [31] All PCLs ACG,American College of Gastroenterology;ACR,American College of Radiology;AGA,American Gastrointestinal Association;BD-lPMN,branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm;CA,carbohydrate antigen 19-9;CT,computed tomography;EUS,endoscopic ultrasound;FNA,fine needle aspiration;MCN,mucinous cystic neoplasm;MD-lPMN,main-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm;MPD,main pancreatic duct;MRCP,magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography;MRl,magnetic resonance imaging;PCL,pancreatic cystic lesion;SCA,serous cystic adenoma.

Guidelines suggest using EUS as a second-line examination in addition to CT/MRI when there are specific risk features, including pancreatitis,cysts >3 cm,enhancing nodules <5 mm,MPD diameter of 5 to 9 mm,thick cyst wall,abrupt changes in MPD diameter with upstream parenchymal atrophy,lymphadenopathy,elevated serum CA 19-9,and cyst growth >5 mm in 2 years.Including EUS-FNA in abdominal imaging significantly increased the accuracy of diagnosing neoplastic PCs.Although guidelines do not clearly define when FNA is necessary during EUS evaluation,performing EUS-FNA in situations with high-risk features associated with malignancy or when a histopathological diagnosis could impact clinical decisions is reasonable.[28-34,41-44]

Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS is essential to better characterize mural nodules.It can differentiate mucin clots from nodules with a high sensitivity,specificity,and accuracy.Studies have shown that contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS-FNA,through an enhancing mural nodule in PCs,is associated with a high rate of positive results for dysplasia or malignancy.[43,44]

5.3.Cyst fluid analysis

Analyzing PC fluid can provide valuable information to improve the accuracy of differentiating mucinous from nonmucinous cysts and determining their malignant potential. However, cyst fluid (CF)analysis alone has a relatively low diagnostic yield(approximately 50%).[41-48]

Several studies have shown that CF CEA levels are higher in malignant or potentially malignant cysts than in benign ones.A CEA threshold >192 ng/L is commonly used to differentiate mucinous from nonmucinous cysts, with a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 84%,and accuracy of 79%.However,there is an ongoing debate regarding the optimal upper cutoff limit for CEA. A CEA level<5 ng/mL is highly specific for nonmucinous cysts (specificity of 95%), whereas >800 ng/mL is highly specific for mucinous cysts(specificity of 98%).[45-47]

Malignant or potentially malignant cysts have lower CF glucose concentrations than benign ones.A CF glucose level <50 mg/dL indicates a mucinous cyst with 91%sensitivity and 75% specificity,whereas CEA showed 67% sensitivity and 80% specificity in the same study population.Intracystic glucose testing has 91%sensitivity,86%specificity,and 94%accuracy,according to a systemic review.Glucose level is a simple and cost-effective biomarker.[46,47]

CA 19-9 is a biomarker associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Elevated CA 19-9 has been linked to high-grade dysplasia and invasive cancer. Guidelines, such as the Fukuoka and AGA guidelines, consider elevated CA 19-9 as a feature of malignancy during PC surveillance.In IPMN,an elevated CA 19-9 level >37 U/mL was found in patients with high-grade dysplasia or invasive cancer,and the proportion increased to 79% using a cutoff value of 100 U/mL.However,there was no correlation between elevated serum CEA levels and malignancy in the patients with IPMN.[48]

Mutations in genes,such as KRAS and GNAS,are strongly associated with MCNs, including IPMNs. These mutations can help identify high-risk PCNs more likely to progress to invasive cancer.In addition, differential expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes can provide further insights into the molecular alterations occurring in cysts and their association with malignant potential.[41-49]

Furthermore,the differential expression of various proteins,glycoproteins, immune modulators, and DNA/RNA/miRNA contributes to risk stratification. Specific proteomic signatures, such as the panel including MMP9,CA72.4,sFASL,and IL-4,have shown promise in identifying high-risk IPMNs.These biomarkers provide additional information regarding the molecular profile of PCNs and can help distinguish between low-and high-risk lesions.[46,49]

Integrating these biomarkers with molecular diagnostic tools and machine-learning algorithms has improved the accuracy of risk stratification.By analyzing the genetic and protein profiles of PCNs,these tools can better predict the need for surgery and help minimize unnecessary interventions. Thus, clinicians can modify treatment plans and surveillance strategies based on an individual's risk profile.[46]

CF cytology has limited diagnostic power owing to the low cellularity of the fluid. New techniques have been developed, including EUS needle cytology brushes and EUS-through-the-needle biopsy.[50,51]However, a randomized controlled trial showed that the cytology brush technique does not improve diagnostic power compared with EUS-FNA.In contrast,EUS-through-the-needle biopsy using a microforceps device through a 19-gauge EUS needle has shown a diagnostic yield of 74%, diagnostic performance of 80%,and an adverse event rate of 5%.[50-52]

6.Surveillance strategies across guidelines:comparisons and contrasts

The revised ICG guidelines recommend a combination of CT,MRI,and EUS for surveillance.[29,30]Cyst size determines the modality and surveillance interval.Patients with main duct involvement,mural nodules >5 mm,or positive EUS cytology require more frequent surveillance. Patients with cysts ≥2 cm and numerous worrisome features are recommended surgery. The AGA guidelines recommend annual MRI for all cysts.Patients who develop morphological changes during surveillance should undergo EUS. The European guidelines for PC surveillance recommend regular follow-up for patients with suspected IPMN,MCN,SCN,or undefined cysts,with intervals and imaging modalities tailored to the cyst type and size.For IPMN, annual follow-up with MRI and/or EUS is advised if there are no surgical indications,with surveillance continued if the patient remains surgically fit.MCNs <40 mm should undergo surveillance every 6 months in the first year, followed by annual surveillance if no changes occur.Patients with asymptomatic SCN are monitored for 1 year, with symptom-based follow-up thereafter,and undefined cysts measuring <15 mm with no malignancy risk factors should be reevaluated after 1 year and,if stable,every 2 years thereafter.In contrast,the 2017 IAP guidelines suggest a more aggressive surveillance based on cyst size,with shorter initial intervals for smaller cysts and an emphasis on any size change or worrisome features triggering repeat EUS, highlighting the significance of the growth rate as a predictor of progression.[30,31]The ACG guidelines provide size-based recommendations for active surveillance strategies in patients with IPMNs or MCNs that do not require immediate resection.Specific surveillance schedules have been proposed based on cyst size,growth,and other features.[32,33]The AGA guidelines recommend stopping surveillance after stable cyst imaging for 5 years.Surveillance may also be discontinued if the patient reaches 80 years of age or is no longer a candidate for surgery (Figure 1).The ACR guidelines recommend discontinuing surveillance after 10 years of stability in low-risk cysts or earlier if the patient reaches 80 years of age or is no longer a surgical candidate.[28-34]

7.Surgical management

7.1.Principles

PCN surgery is complicated and requires careful consideration of many options.This requires a deep understanding of patients'clinical features and personal preferences. In this dynamic process of shared decision making, clinicians explain surgical options, their benefits, and risks, whereas patients share their concerns, aspirations, and lifestyle considerations. Although patient preferences and satisfaction statistics are scarce,evidence indicates a strong preference for surgery because of the fear of cancer. However, the shared decision-making process faces challenges and variability in implementation.Risk prediction and personalized patient education are critical in enhancing effectiveness. This multifaceted approach improves PCN management, patient satisfaction, and overall outcomes and reduces postoperative regrets.

Various guidelines, including the IAP, European, AGA, ACG,and ACR guidelines, dictate the management of PCNs. However,these guidelines differ in terms of their target audience,patient population, types of cysts, indications for surgery, and surveillance methods.[28-34]

The IAP and European guidelines provide surgical indications and recommend the extent of resection for IPMNs.[28-30]The European guidelines offer both absolute and relative indications for surgical intervention, whereas the IAP guidelines differentiate between “high-risk stigmata” and “worrisome features.”[31]The IAP guidelines recommend surgery for cysts ≥3 cm in young,surgically fit patients and consider surgery for cysts ≥2 cm if prolonged surveillance is needed.[28-30]However,the predictive value of these guidelines is suboptimal,with both guidelines missing a certain percentage of malignant IPMNs.[35,36]

Regarding MCNs,the 2018 European guidelines recommend surgical resection for MCNs ≥4 cm, or presence of high-risk features or symptoms.[31]The IAP guidelines no longer address the management of MCNs separately, as evidence supports lifelong surveillance for MCNs <4 cm.[30]The ACG guidelines have a similar management strategy for MCNs and IPMNs,whereas the AGA and ACR guidelines do not differentiate surgical management based on cyst type.[32-34]

In terms of the extent of resection of IPMNs,both the IAP and European guidelines recommend oncologic resection(pancreatoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, or total pancreatectomy) for high-risk lesions.[28-31]Total pancreatectomy may be indicated for MD-or multifocal BD-IPMNs involving the entire gland.However,there is a lack of consensus on the role of total pancreatectomy,parenchymal-sparing resection,and the benefits of lymph node dissection.The decision to perform total pancreatectomy should consider the patient's ability to manage postoperative diabetes and exocrine insufficiency.[53]

Most MCNs in the pancreatic body/tail are managed with distal pancreatectomy.European guidelines recommend oncologic resection with lymphadenectomy and splenectomy if high-risk features are present.[31]Parenchyma-sparing resections may be considered in select patients without suspicious features, but the benefits outweigh the higher short-term morbidity.

Central pancreatectomy and enucleation are alternatives to conventional anatomical resection.Central pancreatectomy is a parenchymalsparing alternative for lesions in the body or neck of the pancreas,whereas enucleation is suitable for low-risk BD-IPMNs.Although both procedures have risks and implications,most PCN operations are oncological resections.[30,31]

Lymphadenectomy is limited in parenchymal-sparing resections,and its value lies in prognostic stratification rather than in survival benefit. Lymph node metastasis is a prognostic factor in PDAC;however,extensive lymph node dissection has not shown a survival advantage.[54,55]

These guidelines are notably based on available evidence and may not provide an optimal predictive value. The management of PCNs should be individualized based on the specific characteristics of each patient, and multidisciplinary discussions involving gastroenterologists,surgeons,radiologists,and pathologists are essential to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

7.2.Specific considerations

In real life scenarios,SCNs are considered an indication for surgery,particularly when they are large and symptomatic. Several factors are associated with the upfront resection of SCNs,including symptoms, larger size, solid cyst components, thick walls, and dilation of the main pancreatic duct. The upfront resection rate has decreased over time, indicating a shift in management strategies. A large single-center study found that 15.4%of patients under surveillance underwent surgery(crossing over to surgery).Increased size,development of symptoms,presence of solid components,and jaundice were associated with crossover to surgery in patients initially under surveillance.Major morbidity occurred in 17.1%of the patients who underwent surgery, and the mortality rate was 1.7%.Macrocystic/unilocular pancreatic body or tail lesions are often misdiagnosed.[56,57]

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies published between 2000 and 2021, comprising 3292 patients with resected MCNs,aimed to determine the malignancy rate of the pancreas and assess the association of high-risk features with malignancy. They concluded that, although current guidelines recommend resection for all MCNs, the malignancy rate in resected MCNs is 16%.This finding implies that surveillance may be appropriate in many cases and that surgical selection criteria should be considered. The size and presence of mural nodules were significantly associated with an increased risk of malignant degeneration.Small MCNs without mural nodules may be more suitable for surveillance than immediate surgery.[58-61]

Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for solid pseudopapillary tumors(SPTs).The specific procedure depends on the location of the tumor.Distal pancreatectomy is common for tumors in the tail/body,whereas pancreatoduodenectomy is used for those in the head/uncinate process. Enucleation may be an option for small tumors located away from the main pancreatic duct.Central pancreatectomy is performed for tumors in the neck or body without vessel involvement.[62,63]

Even with local invasion or metastasis,surgical resection is recommended because of the excellent long-term survival.Some studies have reported positive outcomes after pancreatectomy with vascular resection for SPTs involving the portal vein and its branches.[64-66]In summary,surgical resection completely removes SPTs while preserving pancreatic function,improving long-term survival rates.

Some randomized controlled trials and numerous retrospective studies have demonstrated significant advantages of minimally invasive pancreatic resections.[67,68]Recent international consensus guidelines suggest that minimally invasive pancreatic surgery is comparable to open surgery in high-volume centers. However, increased conversion rates,bleeding,and poor oncological outcomes at low-volume centers cast doubts on its generalized applicability.Because no prospective or randomized studies have been conducted on cystic pancreatic tumors,the data available are biased.The literature is either a subgroup analysis of prospective trials or heterogeneous center-specific retrospective studies.The European guidelines have recommended a minimally invasive approach as“suitable”for cystic tumors of the pancreas as well as parenchyma-sparing procedures like enucleation in selected cases.[67-69]

8.Prognosis

The prognosis after surgical resection of PCNs depends on various factors, including invasive components, subtype, the grade of dysplasia,margin status,and lymph node involvement.Invasive IPMNs have estimated overall survival rates of 50% to 70% at 5 years, whereas resected PDAC has lower rates of 10% to 20%at 5 years.[70-72]

Comparative studies have indicated that the apparent survival benefit of IPMNs is primarily driven by histopathologic features associated with an earlier stage at presentation. Even noninvasive IPMNs have a risk of recurrence after resection and may develop concomitant PDAC in the remaining pancreatic gland. Therefore,long-term postoperative surveillance is required for patients with IPMN.[73]

Surgical resection of MCNs without invasive components is curative. Even for larger lesions, the 5-year survival rate can be 100%if the tumor is restricted within the cyst capsule and has an invasive component.However,patients with mucinous cystadenocarcinomagenerally have a poor prognosis. Approximately 16% of these patients had lymph node involvement at the time of resection,resulting in a 35%5-year overall survival rate.Resected mucinous cystadenocarcinoma had a 3-year overall survival rate of 59%and a median survival of 44 months,according to large series studies.[70-74]

9.Mortality and morbidity

The National Cancer Database reported 2.7% 90-day mortality rate for these procedures.[72]However,no variations were observed in mortality rates based on the type of health care facility.Academic/research centers reported a 1.5% mortality rate, whereas community cancer programs showed 5.4%.[73-78]

Surgical safety practices,particularly by experienced surgeons at high-volume centers,have reduced death rates.A population-based study from California indicated that hospitals performing <25 pancreatectomies yearly had a 4-fold higher in-hospital mortality rate(2.4%) than those performing higher volumes (0.6%). However,low-volume centers perform 65% of all premalignant pancreatic resections.[78-80]

For total pancreatectomy, involving complete pancreatic removal, postoperative mortality was reported to be 2.1% at highvolume centers.An international study based on a registry between 2014 and 2018 found varying mortality rates across countries,ranging from 2% in the United States to nearly 11% in the Netherlands and Germany.[76,80]

Although efforts to concentrate on high-risk surgeries in highvolume centers have implications for disparities in access to care,the argument for seeking care at high-volume centers is particularly strong for premalignant diseases.Because the benefit of surgical resection in preventing cancer is directly related to the mortality risk associated with surgery,the potential mortality cost of intervention may be unacceptably high at low-volume centers, especially for older adults and high-risk surgical candidates.

10.Complications

10.1.Short-term complications

10.1.1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula

Patients undergoing pancreatic surgery for benign or premalignant conditions are 3 times more likely to develop postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) than those with PDAC. POPF remains the primary cause of morbidity and mortality after pancreatic surgery.Approximately 24% of patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy and 20%of those undergoing distal pancreatectomy develop POPF.Of these,5%experienced clinically significant POPF.[81,82]

10.1.2.Delayed gastric emptying

Delayed gastric emptying is a common complication, affecting about 40% of patients undergoing pancreatic surgery. It can lead to prolonged hospitalization,difficulty in oral intake,and the need for alternative nutritional methods.[81-83]

10.2.Long-term complications

Loss of pancreatic tissue and hormonal function can reduce digestive enzymatic activity. This causes malabsorption, steatorrhea,weight loss,and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.The prevalence of exocrine insufficiency after pancreatoduodenectomy ranges from 25%to 65%.[84,85]

Pancreatic surgery can cause pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c).Patients may experience severe fluctuations in glucose levels,which makes diabetes management challenging.The risk of new-onset diabetes after pancreatic surgery ranges from 14% to 15% for all procedures.[81-85]

Other complications include gastrointestinal dysfunction, diarrhea, weight loss, peptic ulcer disease, recurrent hepatopancreatobiliary disorders (stricture, cholangitis, and pancreatitis),incisional hernia,small bowel obstruction,and chronic pain requiring long-term analgesics.

11.From guidelines to clinical practice

Putting guidelines for practice may be a daunting task for physicians. We summarize the conundrum of the available guidelines and propose a step-ladder approach for managing PCNs.First,certain patient factors might have excluded them from this treatment ladder.These include patients older than 80 years with poor health and high-risk comorbidities and those who are obese, given that postoperative complications can be higher in this group.There is literature suggesting that failure to rescue postpancreaticoduodenectomy is 5 times higher in obese patients and warrants delay in surgery in all benign or premalignant lesions before starting the treatment ladder. Furthermore, patients with asymptomatic SCNs that show clear radiological features related to the tumor can also be excluded from the treatment ladder.

The starting point for treatment ladder eligibility includes good health, low-risk comorbidities, and specific diagnostic imaging results. Imaging findings indicating ductal intraepithelial neoplasia(MD-IPMN),solid pseudopapillary neoplasms,MCNs >3 cm,cystic degeneration of adenocarcinoma or cystic neuroendocrine tumors >2 cm, MPD dilatation ≥10 mm with an enhancing mural nodule >5 mm, and obstructive jaundice should prompt further treatment.Patients with EUS findings suggesting main duct involvement, malignant cytology, or specific mutations (KRAS/GNAS,TP53/PIK3CA/PTEN)should be surgically treated.

Patients showing other specific features might also move up the ladder and be evaluated using EUS and CF analysis.These features include cyst size >3 cm,an increase in cyst size >5 mm over 2 years,new-onset diabetes,acute pancreatitis,and CA 19-9 levels ≥37 IU/mL.After EUS and CF analysis,further EUS/MRI monitoring may be needed,with the possibility of definitive surgery or continued surveillance,depending on the development of new high-risk or worrisome features.

Patients with stable imaging findings for 5 to 10 years or those who are older than 80 years and no longer candidates for surgery may be removed from the treatment ladder. This comprehensive approach provides a structured, patient-centered model for managing PCNs.

12.Conclusions

In conclusion,the detection of PCNs is increasing,posing diagnostic challenges to physicians.The lack of valid treatment algorithms and conflicting opinions among experts contribute to the uncertainty surrounding the management of PCNs. This review provides valuable insights into the surgical treatment of PCNs,highlights the low rate of PCN-associated malignancy,and examines the indications for surgery in patients without malignancy or significant symptoms.

Age,sex,history of pancreatitis,preoperative symptoms,and radiological features can help determine the subtype of PCNs and predict their malignant potential.EUS is recommended for malignancy detection and CF or tissue sample examination.Clinical,radiological, and molecular data are crucial to improve the preoperative workup of PCNs.

Clinicians must carefully assess the patient's clinical condition and consider factors such as age, obesity, impaired liver function,and comorbidities when considering surgery.For patients with these risk characteristics, resection should be cautiously recommended,and prehabilitation actions should be considered.

International guidelines do not provide specific technical recommendations for pancreatic cystic lesions. Most PCN resections in these studies were performed using conventional techniques.However,minimally invasive surgery reduces complications and hospital stays.Parenchyma-sparing resections did not increase morbidity or mortality and may be considered in appropriate cases.

Guidelines for lymphadenectomy in PCN resection are unclear.Standard LND should be considered for all IPMN and MCN resection.Future robotic techniques may improve tumor assessment and LND.

In summary,this study emphasizes the need for better diagnostic and treatment algorithms and the importance of individualized decision making in PCN management.Further research,including large multicenter studies and the application of modern data technologies, is necessary to improve patient care in this complex clinical conundrum.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors have no financial support or sponsorship for this article.

Conflicts of interest statement

A.Supe is an editorial board member of Oncology and Translational Medicine.This article is subject to the journal's standard procedures,with peer review handled independently of the relevant editorial board member and his/her research groups.

Author contributions

All authors have significantly contributed to the conceptualization,writing,and editing of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Oncology and Translational Medicine2023年6期

Oncology and Translational Medicine2023年6期

- Oncology and Translational Medicine的其它文章

- FGF2 promotes the chemotherapy resistance in colon cancer cells through activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

- Development of therapeutic cancer vaccines using nanomicellar preparations

- Immunotherapy for mucosal melanoma

- Proposal of a modified classification for hilar cholangiocarcinoma

- Chinese expert consensus on laparoscopic hepatic segmentectomy and subsegmentectomy navigated by augmented-and mixed-reality technology combined with indocyanine green fluorescence imaging

- Xiao-Ping Chen:the “Master of the Scalpel” who saves lives by entering the forbidden territory of hepatopancreatobiliary surgery