Small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan

Rul AWAD , Hosm TITI, Aziz MOHAMED-BRAHMI,Mohme JAOUAD, Aziz GASMI-BOUBAKER

a Department of Animal Production, National Agronomic Institute of Tunisia, Carthage University, Tunis, 1082, Tunisia

b Department of Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture, the University of Jordan, Amman, 999045, Jordan

c Higher School of Agriculture of Kef, Laboratory for the Sustainability of Production Systems in the North-West Region, University of Jendouba,Kef, 7119, Tunisia

d Institute of Arid Regions Médenine, Laboratory of Economy and Rural Societies, Médenine, 4119, Tunisia

Keywords:Value chain analysis Small ruminants Strengths, weaknesses,opportunities, and threats (SWOT)analysis Climate change Livestock production management Jordan

ABSTRACT: This study aims to assess the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan, to identify the potential intervention areas that could improve the production efficiency and guarantee the sustainability of the small ruminant sector in this area.Sheep breeding is the source of livelihood for most of the people in Al-Ruwaished District, which is characterized by the large number of sheep and goats.We surveyed 5.0% of the small ruminant holders in the study area and conducted individual interviews and surveys with the potential actors in the value chain to undertake a small ruminant value chain analysis.From the survey, we found that the small ruminant value chain consists of five core functions, namely, input supply, production management, marketing, processing, and consumption.Despite the stable impression given by the large number of holdings in the small ruminant sector,the surveyed results show a clear fragility in the value chain of small ruminants in this area.The small ruminant production system is negatively impacted by climate change, especially continuous drought.In addition, the high prices of feed that the farmer cannot afford with clear and real absence of the governmental and non-governmental support activities also impact the development of the value chain.The results of strengths, weaknesses,opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis reveal that the major constraints faced by this value chain could be divided into external and internal threats.Specifically, the most prominent external threats are the nature of the desert land and continuous drought, while the major internal threats are the absence of appropriate infrastructure, shortage of inputs, and weakness in the production management and marketing.We proposed solutions to these challenges to ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of the sector, such as the formulation of emergency response plans to severe weather, qualifying farmers’ skills, and establishment of agricultural cooperative societies.

1.Introduction

The small ruminant sector plays a crucial role in arid and semi-arid regions (Berihulay et al., 2019; Kumar et al.,2022).Small ruminants are particularly well-suited to these regions because they adapt to harsh and dry conditions and can subsist on low-quality feed (Kumar and Roy, 2013).The significance of small ruminants goes beyond mere sustenance for people living in arid environment.They serve as vital contributors to the livelihoods of millions of rural individuals, specifically benefiting landless, marginal, and small farmers in arid and semi-arid regions (Joy et al., 2020; Tella and Chineke, 2022).Due to their immense importance, there is a need for comprehensive studies that thoroughly examine the small ruminant value chain in specific geographical contexts.Value chain offers a comprehensive overview of the various individuals, tasks, services, prospects, and obstacles involved in the movement of specific small ruminant products and associated services, including everyone from input suppliers and farmers to end buyers and consumers (Alary et al., 2009; Duguma et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2015a; Wanyoike et al.,2023).Value chain is not only helpful in understanding these dynamics but also acts as a structured framework for assessing potential development initiatives (Gebregziabhear, 2018).

Al-Ruwaished District of Jordan is the subject of this study since it has received little attention from prior studies.Al-Ruwaished District is a region that has difficult economic conditions and restricted access to resources, and it is regarded as one of the country’s pockets of poverty (Shwaqfeh, 2006).Around 208 thousand heads of cattle are kept in small ruminant farming in Al-Ruwaished District, which makes up more than 5.0% of all small ruminant animals in Jordan, distributed among 326 farmers.Due to the region’s challenging geology and arid desert climate, the small ruminant sector in Al-Ruwaished District has obstacles similar to those faced by other sectors (Shwaqfeh, 2006).Consequently, small ruminant holders and the local population experience hardship, leading to an increase in poverty rate (Shwaqfeh, 2006).By delving into this specific region, the study aims to shed light on the value chain associated with small ruminants and their potential for improving livelihoods in an underrepresented locality.The motivation behind this study stems from the lack of comprehensive analysis of the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District.Despite their potential to improve rural development and alleviate poverty, small ruminants in this region remain largely understudied.By conducting an in-depth investigation into the value chain dynamics, this study aims to fill this research gap and highlight the importance of considering the unique characteristics of such marginalized areas.Furthermore, covering the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District holds significant relevance in a global context.Recognizing and comprehending the difficulties faced by areas of extreme poverty is essential, as putting up practical solutions to strengthen those areas is vital.By doing this research and disseminating the findings,we hope to provide insightful commentary to the larger discussion on small ruminant value chain and help to improve rural lives not only in Jordan but also in other places across the world.The creation of focused interventions and activities to maximize the potential of this key industry has been hampered by the lack of a thorough understanding of the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District.Furthermore, a thorough knowledge of the underlying issues and opportunities that exist within the small ruminant value chain in this particular area has been hampered by the absence of empirical evidence.Consequently, this research seeks to address the following key questions:

(1) What are the prevailing constraints and challenges faced by small ruminant farmers in Al-Ruwaished District,regarding the entire small ruminant value chain from production to market?

(2) What are the existing market systems and institutions in Al-Ruwaished District, and how do they shape the dynamics of small ruminant value chain?

(3) What are the opportunities and potential interventions that can be identified to enhance the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, thus leading to improved livelihoods for local farmers?

Through a comprehensive analysis of the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, this study not only aims to contribute to the existing body of knowledge but also provides evidence-based recommendations for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners in agriculture and rural development, with the ultimate goal of driving positive change in the lives of small ruminant farmers in marginalized areas worldwide.

2.Methodology

2.1.Study area

Al-Ruwaished District (32°30′15′′N, 38°12′04′′E) is situated in the northeastern part of Jordan, sharing borders with Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.Administratively, Al-Ruwaished District falls under the jurisdiction of Mafraq Governorate and is located at an elevation of 683 m a.s.l.It is recognized as the least populated district in Jordan, with an estimated population of 8680 people, residing across an area of 21,000 km2(Department of Statistics, Government of Jordan, 2021).The district primarily consists of the desert plateau of Badia that includes the Al-Hammad basalt lands.Al-Ruwaished District is characterized by a hot desert climate, with variable precipitation (50–100 mm)(Department of Statistics, Government of Jordan, 2020).The average annual temperature in the area ranges between 18°C and 20°C (Ababsa, 2014).Vegetation in Al-Ruwaished District is scarce, with only a few desert shrubs like yarrows (Shwaqfeh, 2006).The main water source in the area is groundwater, supplemented by some valley streams,earthen dams, and pits (Shwaqfeh, 2006).Livestock production in Al-Ruwaished District is primarily focused on sheep (accounting for 94.0% of the total livestock population), with smaller numbers of goats and camels.The estimated population of sheep, goats, and camels in the area are almost 199,000, 9000, and 3000, respectively.

2.2.Data collection

We adopted differentiation advantage for small ruminant value chain analysis (MKSP, 2016) to identify the chain activities and describe the role of the actors in these activities to further ascertain the potential options for intervention.The results reported in this paper are mostly based on the primary data gathered from different potential actors in the value chain in 2021.Due to the clear geographical and social homogeneity of the study area (Shwaqfeh, 2006) and difficulty of reaching potential actors in the value chain, we chose only 5.0% of small ruminant holders to conduct the survey according to Khader (2013).We randomly selected 16 small ruminant holders for simple random sampling along the eastern Badia.We conducted a structured survey focused on the main aspects of small ruminant’s production as input supplies, husbandry practices, processing, marketing, and consumption.Individual interviews with the other potential actors in the value chain were also used to undertake small ruminant value chain analysis, which included all health care suppliers, a governmental services provider, 15 traders, 3 processors, and 10 local consumers.The Animal Care and Use Committee at the Deanship of Scientific Research, the University of Jordan reviewed and approved experimental design and procedures.All procedures in this study concerning human and animal rights were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975, as revised in 2000.

2.3.Statistical analysis

We utilized a thematic analysis approach to analyze the survey data by the IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27 software(International Business Machines Corporation (IBM Crop.) Armonk, NewYork, the USA), and calculated the quantitative data by using descriptive statistical techniques.We employed the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities,and threats (SWOT) analysis to identify the opportunities and threats related to small ruminant value chain in the study area.

3.Results and discussion

3.1.Actors and functions of small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District

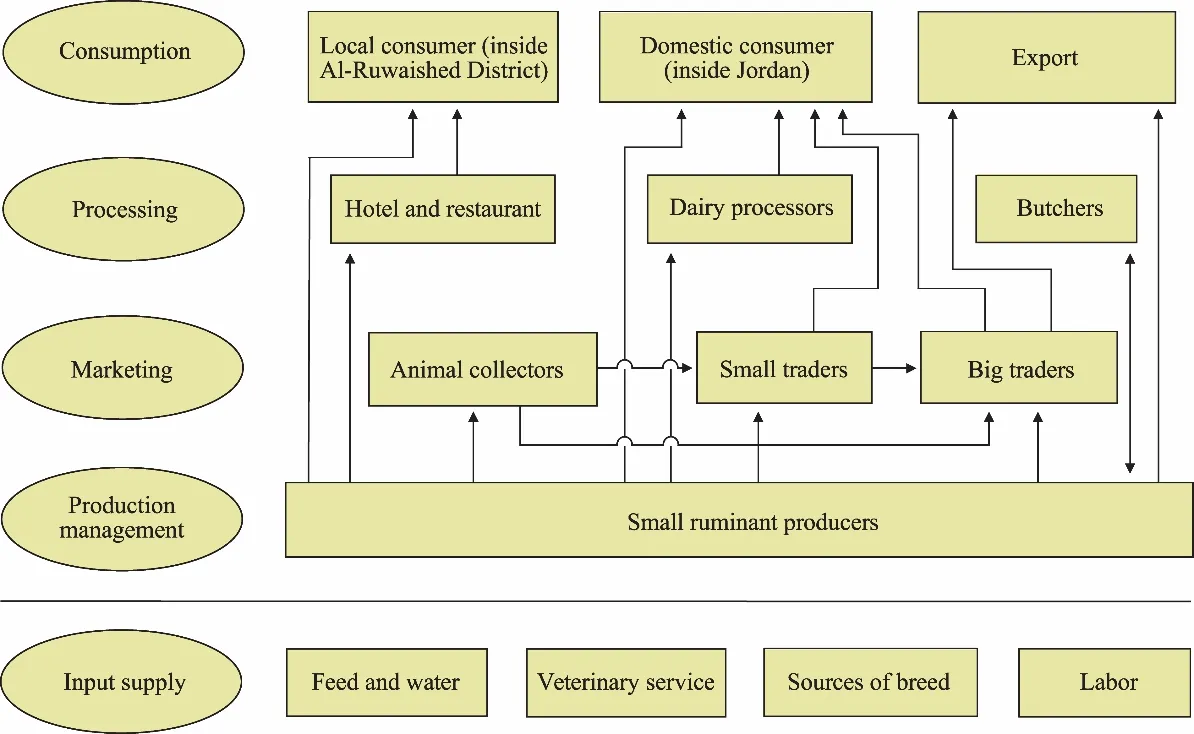

The small ruminant value chain consists of five core functions (input supply, production management, marketing,processing, and consumption) that are analyzed within the input-output structure (Shah et al., 2015a; Chakraborty and Gupta, 2017).Figure 1 shows the activities and actors across the five functions of the small ruminant value chain in the study area.

Fig.1.Five functions of the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan.

3.1.1.Input supply

Input supply for small ruminants’ production includes material inputs (source of breeds, feeds, vaccines, and medications) and service inputs (credit services, capacity building services, animal health services, and labor) (Shah et al., 2015a).In Al-Ruwaished District, the input supply is breed, feed and water supply, veterinary service, and labor.This converges the critical inputs required for meat and dairy production of small ruminants in Liberia, which include animals, feed, water, and veterinary medicines/vaccines (Touray, 2017).

Not all small ruminant owners keep goats alongside their sheep, and roughly 44.0% of them do so.All small ruminant owners raise sheep of the awassi breed, which is the most prevalent breed in the eastern Mediterranean and has adapted to desert conditions with low precipitation (Al-Najjar et al., 2021).The dearth of shrubs and browsing flora suited for the production of goats, the climate and the character of the desert location may all be contributing factors for the dearth (Katiku et al., 2013).In Al-Ruwaished District, the desert goat, which makes up 86.0% of all goats, is the most prevalent breed.Their original flocks served as the source of their livestock.Farmers usually adopt sustainability out of stock to replace their herds, which matches the situations adopted by small ruminant producers in Lebanon (MercyCrops, 2014; Hosri et al., 2016), northeastern Syria (Care International – Syria Office and iMMAP,2018), and Bahawalpur District in Pakistan (Shah et al., 2015b).However, in the study area, the situation was somewhat different in 2021, when 69.0% of the weaned lambs and kids (about two months old) were sold at an average price of 167.93 USD/head of sheep and 130.14 USD/head of goat.None of the farmers purchased new animals in 2021 due to the high cost of production and complete drying of the rangelands in recent years.

Farmers mainly feed their animals with subsidized feed, and barley and wheat bran are sold to small ruminant farmers at prices offered by the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture.The amount of subsidized feed sold to each farmer is determined by the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture.According to this protocol, the support covers 90.0% of the holdings of sheep and goats at a level of 20 kg/(head•month) of barley, while the amount of bran varies based on the Kingdom’s production of wheat bran, reaching 500 g/(head•month) in good season and decreases to 250 g/(head•month) in other seasons.A ton of subsidized barley is sold at 244.00 USD compared to 332.36 USD for unsubsidized.In the meantime, a ton of wheat bran that has been given subsidies is sold for 107.75 USD as opposed to 218.31 USD for unsubsidized.Even when the feed quantity was insufficient for the entire flock, more than 43.0%of breeders do not purchase supplemental feed.Due to their inability to purchase unsubsidized feed and the paucity of available wheat bran at all times within the feed distribution warehouse (the only source of feed in Al-Ruwaished District), some herders claimed that they occasionally have to feed one meal of barley to their animals.It is worth mentioning that the Ministry of Agriculture of Jordan reduces this amount annually by 20.0% to dispose of fake holdings.As previously reported, the Ministry of Agriculture of Jordan provides support on barley and bran materials based on a card proving the number of holdings for each farmer, sometimes the farmer sells his animals without modifying the numbers recorded in that card and thus the farmer will pass through the support in a greater amount than allocated to him).Whenever a farmer has to contact the Directorate of Agriculture and submit an objection, the verification committees adjust the quantity after verifying the asset numbers, constituting a financial burden for the farmer during the verification period.Small ruminant farmers in northern Syria experience similar issues during the pasture shortage season, as many of them were compelled to cut back on the amount of daily feed they could afford to raise their animals (Care International – Syria Office and iMMAP, 2018).In contrast to the fact that most of the district’s soils are unsuitable for agriculture due to high salinity, crop production is uncommon in the study region(Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 2005).Results of our survey revealed that 57.0% of farmers have moved to water sources to raise their animals, 37.0% of them are forced to transport water using water tanks,and 6.0% are permanently next to water sources.

The presence of veterinarian extensions is the key to the successful improvement of livestock sector, especially for small ruminants (Namonje-Kapembwa et al., 2019).In Jordan, the Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for animal health services, and the governorate veterinary directorates provide free veterinary services, including vaccinations for foot and mouth disease (FMD), peste des petits ruminant’s disease (PPR), sheep and goats’ pox, brucellosis, and anthrax (Braam, 2022).This is also the case in the Chakwal District of Pakistan, where vaccination is the main service provided by the public sector to farmers (Shah et al., 2015a), while in the Beitbridge District of Zimbabwe, the supply of veterinary medicines consists of both the State Veterinary Department and private companies providing animal health products and animal health-related services to clients (Dube et al., 2017).The Ruwaished Agriculture Directorate is the governmental side responsible for providing veterinary services in the study area.There is a shortage of veterinary staff in Ruwaished Agriculture Directorate, as there is only one veterinarian, an agricultural engineer,two veterinary nurses, and eight agricultural workers.The study area lacks a veterinary hospital or lab, which is a part of the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture.There are just two veterinary pharmacies in the private sector.An agricultural engineer who works at one of these pharmacies gives sheep owners the necessary veterinary advice and/or diagnoses the illness.In Al-Ruwaished District, there is no private veterinary clinic.The agricultural directorates offer free mandatory vaccinations, as mentioned earlier.The non-permanent availability of these vaccines in the directorate’s storage, however, resulted in 31.0% of farmers being forced to purchase vaccines on their own dime; and due to the exorbitant cost of pharmaceuticals, all farmers are also required to purchase pharmaceuticals on their own dime.

Al-Ruwaished District lacks any financing services.If the required guarantees are available, the financing services are from outside of the district.Only 12.5% of the farmers are able to get loans from the Agricultural Credit Corporation, which is a governmental agency.Breeders in Al-Ruwaished District do not have access to capacity building services as there is no such activity from governmental or non-governmental institutions.According to Kassahun et al.(2021), using credit services significantly and positively affects market participation and the level of participation in the small ruminant market, as it can be argued that those farmers who have access to formal credit are more likely to participate in the small ruminant market than those who do not have access to formal credit.In the absence of formal and specific credit services for sheep and goat production, funding sources can be provided to small ruminant farmers through some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Shah et al., 2015b), such as rural microfinance institutions, family asset building programs, rural savings, and credit associations (Legese et al., 2014).Farmers can also get credit from informal intermediaries whose upfront financing is characterized by exorbitant interest rates (Touray, 2017).

Family employment is prevalent in Al-Ruwaished District, according to the survey data; family labor accounts for 75.0% of the aggregate labor force of one small ruminant household, and this situation is somewhat similar to many countries.For example, low-input pastoral systems in marginal arid regions of Mali (CIAT et al., 2011) depend on family labor and so they are in the northeast of Syria (Care International – Syria Office and iMMAP, 2018).There was no paid local labor in the study area and 25.0% of small ruminant holders surveyed employed foreign workers.The most prominent paid labor is Sudanese, at 16.6%, followed by Egyptian, at 8.4%.

3.1.2.Production management

In Al-Ruwaished District, small ruminant farming is considered traditional family breeding used for subsistence.It is the main source of income for 83.0% of the study samples and the only source of income for 90.4% of them.Young people (20–40 years old) are the most common group among the producers, with only 8.0% of them over the age of 60 years old.Over 59.0% of the small ruminant producers in Al-Ruwaished District are illiterate while the rest of them are at high school level (Tawjhi) or less.These results fully correspond to demographics and statistics with the report of the Jordanian Ministry of Planning for the year 2005 (Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation,2005).Sheep and goats’ producers who were included randomly in the study can be divided into three groups: large holder producers (holding 500 heads or more), accounting for 42.0%; medium holder producers (holding 100–499 heads), accounting for 50.0%; and smallholder producers (holding less than 100 heads), accounting for 8.0%.These are very close to the statistics published by the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture, where the large, medium, and small ruminant holder producers are distributed as 45.0%, 45.0%, and 10.0%, respectively (Department of Statistics,Government of Jordan, 2020).The study area is characterized by an extensive production system (92.0%), while the intensive production system only accounts for 8.0%.Most producers feed their animals barley and wheat bran once daily throughout the year.About 67.0% of herders move regularly with their flocks in search of water sources,compared to 16.0% of herders who do not follow a pattern in their movement, of which only 25.0% travel outside the study area in summer.These results are similar to previous findings on the Jordanian Badia (the steppe lands of Jordan) in terms of the dominance of an extensive production system (Betts, 1993; Abu-Zanat et al., 2005).Abu-Zanat et al.(2005) mentioned that 59.2% of farmers adopt a transhumance system in the middle Badia of Jordan.All visited producers confirmed that the rangeland has completely dried up in recent years.Crop-small ruminant mixed farming system is found by 8.0% of the farmers of those who travel outside the district in summer.Open areas and temporary structures are commonly used for keeping small ruminants in the study area (Fig.2a).In the study area, there is an absence of designated feeders, drinkers, or appropriate storage facilities for feed (Fig.2b and c).Providing a suitable housing system is probably the most effective way to protect small ruminants from adverse weather (Wadhwani et al., 2016).Shah et al.(2015a) stated that adequate housing is important for better care, as well as improved productivity.In the Bahawalpur District of Pakistan with semi-deserts, livestock is not protected against cold in winter and heat in summer, and small ruminants are commonly kept in open areas, tree shades, shrubs, and temporary structures (Shah et al., 2015b).

Fig.2.Small ruminant management and marketing in Al-Ruwaished District, Jordan.(a), open areas used for keeping small ruminants; (b), small ruminant drinkers; (c), small ruminant feeders; (d), live animal market.

Breeding is entirely natural in the study area.Similarly, breeding is quite natural in the Bahawalpur District of Pakistan, Lebanon, and Abu Dhabi Emirate of United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Shah et al., 2015b; Hosri et al., 2016;Tabbaa et al., 2018).Gilbert and Miles (2017) pointed out that in environments where adaptation is critical, natural selection is preferred.Although better performance is achieved in traditional systems where breeding is uncontrolled(Wilson, 1989) and despite the herders’ lack of sufficient skills, about 25.0% of the surveyed herders use sponges to improve production, expedite the time of birth, and match the season of selling animals abroad for getting higher prices.Sponges are inserted by the herders themselves.Most stakeholders were not able to accurately determine the success rate of fertilization due to the integration of males with females all the time.However, it is clear that the fertilization rate is low and this may be attributed to the lack of feed and poor husbandry practices.

Due to the lack of veterinarians, farmers resort to diagnosing the disease and giving the necessary vaccines and medicines themselves.Most of the farmers do not have a specific place to isolate sick animals.Although 75.0% of breeders think that regular vaccination is important, only 58.0% of them follow a vaccination calendar and regularly vaccinate their herds.Several diseases were reported for small ruminants in the study area with pasteurella being reported as the major disease.This could be due to the harsh weather in the study area, which exposes animals to heat stress.According to Brogden et al.(1998), exposure to inclement weather is a major factor in pasteurella.Other diseases like mastitis, sheep and goats’ pox, pneumonia, brucellosis, diarrhea, and PPR were also reported.These are close to the diseases that were monitored in northern Jordan by Al-Assaf (2012).Animal health service providers have agreed with farmers that veterinary services for small ruminants are a financial burden on the breeders and the services are insufficient.

It is difficult to determine the quantities of milk produced, as farmers do not have records or calculate the production costs.In addition, they are not interested in knowing profitability.Most of producers (75.0%) also use milk for suckling lambs and kids, as milk produced from their dams is hardly enough for them.However, 25.0% of herders produce milk either for in-house or self-consumption or sold to dairy processors.Feed shortage leads to the use of milk mainly for lambs and kids (Shah et al., 2015a).All the goat holders mentioned that goats’ milk is not desirable to dairy processors, and it is produced almost for in-house consumption.The herders sold milk for dairy processors indoors at an average price of 0.98 USD/L.Small ruminant dairy processors come from outside the district during the season of milk production (after mid-November to the end of March in the next year) and temporarily set up mobile tents among farmers for milk processing white cheese, Baladi ghee (the traditionally ghee in Jordan (Samen Baladi)is one of anhydrous dairy products that produced from either bovine, or goat, or sheep milk, or blend of these), and Jameed (a Middle Eastern food consisting of hard, dry yogurt made from ewe or goat’s milk and the primary ingredient used to make Mansaf, the national dish of Jordan).It is of great interest that those dairy processors are not licensed and not subjected to health control in their products with minimal use of hygiene and food safety standards.Shearing is carried out once a year and the majority farmers shear the sheep themselves during summer (June to August).However, 33.0% of farmers pay 1.40 USD/head for shearing, which is considered an additional non-profit cost.Most farmers are troubled by how to get over shearing waste, and some of them resort to burning it.Wool production is uncommon in the study area with no one buying wool there.

3.1.3.Marketing

Marketing includes all the activities necessary to move the products from producers to consumers (Hussen et al.,2013).According to the stakeholders’ responses, the sheep market in Al-Ruwaished District is generally oriented toward export, which accounts for 62.0% of the total ruminant trade, followed by domestic transaction (29.0%, trading inside Jordan) and local transaction (9.0%, trading inside Al-Ruwaished District).Emphasizing that these ratios are estimated according to stakeholders’ responses.Most of the small ruminant producers in the study area sell their animals to meet cash demand.In general, the traders directly collect the lambs indoors, where they use large trucks to transport the animals to their distribution places.Though it is not common for them to go to live animal markets to sell their animals.Nearly 17.0% of them go to live animal markets in case they need cash to sell their animals.Most stakeholders mentioned that there are no specific sheep traders inside Al-Ruwaished District.Any trader, even foreigner can bring his/her truck during the weaning season and buy his/her needs from farmers.

There is no formal live animal market in the study area.Few farmers gather each morning in a known open area to sell their animals in limited numbers (Fig.2d).The market has no infrastructure, and trading in the market follows supply and demand.According to herders, supply and demand are closely related to the Gulf markets.As 26.0% of the interviewed traders revealed, they buy weaned lambs and then raise them in private farms for exporting.Male lambs are exported to the Gulf at the age of eight months, while females are sold inside domestic markets.Interviewed traders mentioned that the profit margin is about 27.99–41.98 USD/head.It was reported that traders from the Gulf come to the district and buy sheep to export them to their country after giving them the necessary vaccinations.Locally, there are just two restaurants in the district.Owners of these restaurants have their sheep flocks and rely mainly on restaurants’ consumption.They often buy more animals to cover the consumption of the customers coming to restaurant.The purchase was directly from the producers.

3.1.4.Processing

As mentioned above, minority farmers produce the dairy products by themselves or by outside dairy processors for home consumption.For meat processing, it is mainly carried out by a hotel and a restaurant present in the study area.Both of them serve dishes based on sheep meat only, as goat meat is not desirable in the study area, in addition to selling raw meat directly to the local consumers.It should be noted that there are no butchers in this district except the butchers of the hotel and the restaurant, who sell raw meat as individual cuts for 13.99 USD/kg and internal organs for 8.40 USD/kg.The restaurant and the hotel are subject to the supervision of the Jordanian Ministry of Health to ensure food safety.Generally, 80.0% of local consumers buy live animals from producers and slaughter animals themselves.

3.1.5.Consumption

Mostly, the local community depends on manufactured dairy products that are sold in supermarkets.Up to 90.0%of the study samples stated that they do not desire dairy products.The rest buy dairy products from the dairy processor directly.Most of the dairy products are consumed by domestic consumers.Local meat consumers (many of whom are also producers) consume just awassi meat.According to the stakeholders, it is customary within the study area that ewes are consumed locally and the lambs are left for export.The demand for sheep increases before the Eid al-Adha,and they are sold outside the Al-Ruwaished District.

3.2.Impact of climate change on small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District

Environmental issues are particularly important in the small ruminant value chain, due to the dependence of this kind of farming on open grazing and the feeding of bulk feed material (CNFA, 2016).The lack of forage resulting from the scarcity and unpredictability of precipitation, along with prolonged drought, harm the production of small ruminants (Shah et al., 2015b).According to Sejien et al.(2013), climate change seriously affects the availability of pastures during the period of recurrent droughts.Besides, severe climatic changes may impose various pressures on animals, which will negatively affect their production and reproduction (Sahoo et al., 2013).

In the study area, 87.5% of the herders included in the study reported that temperature has increased in the long term, and 93.8% of them stated that they notice a negative variation in precipitation rate and all of them confirmed that the rangelands are affected negatively, to the extent that these rangelands are completely absent in recent years.Farmers attribute this deterioration to the climatic conditions that prevail in the study area, such as the decrease in precipitation rate and high frequency of dust storms that prevent the growth of shrubs and grasses.About 93.8% of the breeders confirmed that they suffer from high costs as a result of climate change, as they are forced to rely on high-priced feed completely, and climate change has had a negative impact on the health of their animals.Half of the surveyed holders express their lack of interest in the issue of climate change and no one of them alters his/her herd management except the obligation of providing feeds to their animals.

3.3.Strgenths, weakenesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis of small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District

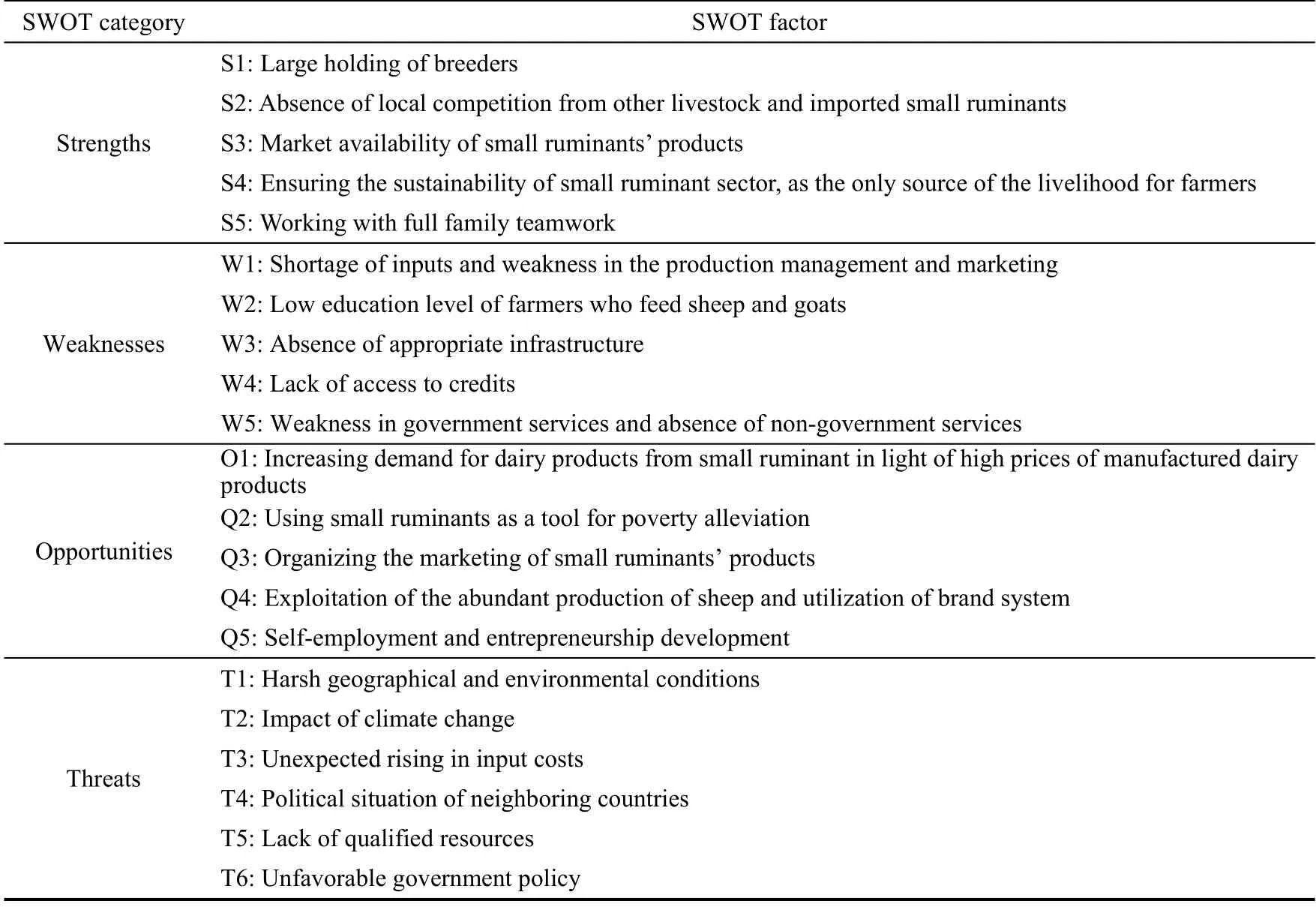

SWOT analysis is an analytical approach used to discover the best match of internal resources and key competencies to develop competitive advantages and identify the limitations faced by the sector, so it helps planners to identify factors associated with external opportunities and threats with internal strengths and weaknesses (Istaitih and Yelboğa, 2018).SWOT framework with the main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of small ruminant value chain in the study area is shown in Table 1.The analysis revealed that the major constraints faced by this value chain can be divided into external and internal threats, of which external threats are the nature of the desert land and continuous drought, while the internal threats include the absence of appropriate infrastructure, the shortage of inputs, and weakness in production management and marketing.However, despite these limitations, there are still opportunities to improve the value chain.

Table 1List of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis for small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District.

The potential interventions along the value chain as solutions to those challenges are as follows:

(1) Formulation of emergency response plan for severe weather conditions.The concerned authorities should formulate emergency response plan to mitigate the impact of climate change, such as activating the Environmental Compensation Fund, and increasing the amount of barley and wheat bran subsidized to farmers to cover the needs of animals during the drought periods.

(2) Capacity building of farmers.Establishing specialized extension centers or activating government agricultural extension within Al-Ruwaished Agriculture Directorate to qualify the young workforce in the fields related to production management and marketing.

(3) Establishment of agricultural cooperative societies.Establishing agricultural cooperative societies could direct the projects of NGOs and support the development of small ruminant sector in the study area by establishing partnerships with relevant NGOs working in the agricultural sector.These collaborations will enable cooperative societies to access technical expertise, financial support, and market linkages.NGOs can also provide guidance on sustainable farming practices and assist in the implementation of innovative projects.Through the cooperative societies, members will have better access to resources such as veterinary services, feed, equipment, and credit facilities.By leveraging collective bargaining power, cooperative societies can negotiate better prices for inputs and secure favorable terms for loans.

4.Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwashid District, Jordan,highlighting its strengths, weaknesses, and key constraints.The findings indicate that the value chain is not well organized, with unclear roles and functions of the actors involved.The study also reveals that climate change specifically continuous drought, lack of input supplies, and a weak support system from governmental and nongovernmental entities, have adversely affected the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwashid District.

To address these challenges and promote the development of the small ruminant sector in the study area, it is imperative to consider the identified weaknesses and threats.The study proposes potential interventions that should be implemented along the entire value chain.These interventions include the collaboration between relevant authorities to mitigate the effects of climate change, capacity-building programs to enhance farmers’ skills and knowledge, and the qualification of a skilled workforce in production management and marketing.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study.The research was conducted in a specific district and may not fully represent the broader context of small ruminant value chain in Jordan.Therefore, attention should be exercised when generalizing the findings.Additionally, this study relies on primary data collected through surveys and interviews, which may be subject to respondent bias and recall errors.Despite these limitations, this study serves as a valuable foundation for further research and policy development in the field.

Based on the findings, several policy recommendations can be put forth.Firstly, targeted investments in market infrastructure are necessary to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of the value chain.Secondly, capacitybuilding programs should be implemented to enhance technical knowledge and skills among farmers, particularly in sustainable and climate-resilient practices.Thirdly, collaboration among stakeholders (including government agencies, farmers’ associations, and private sector actors) is crucial for fostering coordination and collective action in the development of small ruminant value chain.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwashid District.The findings will inform policymakers, practitioners, and other stakeholders in their efforts to enhance the efficiency,competitiveness, and resilience of the small ruminant value chain in Jordan.Further research and policy initiatives are encouraged to build upon these findings and address the broader context of small ruminant value chain in the country.

Authorship contribution statement

Rula AWAD: conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, and writing - original draft; Hosam TITI: formal analysis, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing; Aziza MOHAMED-BRAHMI: conceptualization,formal analysis, and writing - review & editing; Mohamed JAOUAD: formal analysis and writing - review & editing;and Aziza GASMI-BOUBAKER: conceptualization and writing - review & editing.

Ethics statement

The Animal Care and Use Committee at the Deanship of Scientific Research, the University of Jordan reviewed and approved experimental design and procedures.All procedures in this study concerning human and animal rights were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975,as revised in 2000.In addition, the participants provided their informed consent to participate in this survey.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our sincere acknowledgement to the staff working for the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture and Al-Ruwaished Agriculture Directorate.Their support, cooperation, and provision of necessary resources are instrumental in the successful completion of this study.Their valuable input has greatly enriched this study and enhanced its credibility.

We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of all the participants and stakeholders involved in this research.Their willingness to share their knowledge, experiences, and perspectives was essential in understanding the complexities of the small ruminant value chain in Al-Ruwaished District.

- 区域可持续发展(英文)的其它文章

- Economic complexity and environmental sustainability in eastern European economies: Evidence from novel Fourier approach

- Supplemental feeding on rangelands: new dynamics of the livestock in the El Ouara rangelands in southern Tunisia

- Social interactions in periodic urban markets and their contributions to sustainable livelihoods: Evidence from Ghana

- How Himalayan communities are changing cultivation practices in the context of climate change

- Rural sustainable development: A case study of the Zaozhuang Innovation Demonstration Zone in China

- Toward a sustainable future:Examining the interconnectedness among Foreign Direct Investment (FDI),urbanization, trade openness, economic growth, and energy usage in Australia