Physiological and biochemical characteristics of boscalid resistant isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from asparagus lettuce

SHI Dong-ya , LI Feng-jie ZHANG Zhi-hui XU Qiao-nan, CAO Ying-ying Jane Ifunanya MBADIANYA LI Xin WANG Jin CHEN Chang-jun#

1 Department of Pesticide Science, College of Plant Protection, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, P.R.China

2 Jiangsu Pesticide Research Institute Co., Ltd., Nanjing 210046, P.R.China

Abstract Laboratory mutants of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib) de Bary, resistant to boscalid, have been extensively characterized.However, the resistance situation in the lettuce field remains largely elusive.In this study, among the 172 S.sclerotiorum isolates collected from asparagus lettuce field in Jiangsu Province, China, 132 isolates(76.74%) exhibited low-level resistance to boscalid (BosLR), with a discriminatory dose of 5 μg mL-1.In comparison to the boscalid-sensitive (BosS) isolates, most BosLR isolates demonstrated a slightly superior biological fitness,as evidenced by data on mycelial growth, sclerotium production and pathogenicity.Moreover, most BosLR isolates showed comparable levels of oxalic acid (OA) accumulation, increased exopolysaccharide (EPS) content and reduced membrane permeability when compared to the BosS isolates.Nevertheless, their responses to distinct stress factors diverged significantly.Furthermore, the effectiveness of boscalid in controlling BosLR isolates on radish was diminished compared to its efficacy on BosS isolates.Genetic mutations were identified in the SDH genes of BosLR isolates,revealing the existence of three resistant genotypes: I (A11V at SDHB, SDHBA11V), II (Q38R at SDHC, SDHCQ38R)and III (SDHBA11V+SDHCQ38R).Importantly, no cross-resistance was observed between boscalid and other fungicides such as thifluzamide, pydiflumetofen, fluazinam, or tebuconazole.Our molecular docking analysis indicated that the docking total score (DTS) of the type I resistant isolates (1.3993) was lower than that of the sensitive isolates (1.7499),implying a reduced affinity between SDHB and boscalid as a potential mechanism underlying the boscalid resistance in S.sclerotiorum.These findings contribute to an enhanced comprehension of boscalid’s mode of action and furnish valuable insights into the management of boscalid resistance.

Keywords: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, boscalid, asparagus lettuce, SDHBA11V, SDHCQ38R

1.Introduction

Sclerotinia stem rot (SSR), caused by the necrotrophic plant-pathogenic fungusSclerotiniasclerotiorum(Lib)de Bary, poses a significant threat to agriculture.This fungal disease severely impacts over 400 cultivated plant species, including economically important crops like oilseed rape, peanut, sugar beet, soybean and lettuce(Boltonet al.2006; Derbyshireet al.2017).Owing to the commercially SSR-resistant cultivars unavailable,fungicide deployment remains the principal strategy for SSR control across the majority of crops (Matheron and Porchas 2004; Duanet al.2012; Xuet al.2014; Weiet al.2017).Currently, anti-tubulin fungicides (MBCs,i.e., carbendazim) and dicarboximides (i.e., iprodione,procymidone and dimethachlon) constitute the mainstay for SSR management (Maet al.2009; Kuanget al.2011;Wanget al.2016).Nonetheless, the pervasive and extensive application of these fungicides has led to the emergence of resistantS.sclerotiorummutants in the field(Wanget al.2014; Zhouet al.2014).Consequently, it is imperative to identify alternative fungicides with different modes of action to mitigate the risk of fungicide resistance development (Zhenget al.2017).Although the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) has introduced 55 classes of fungicides, the class experiencing the most rapid expansion in terms of new product introductions is that of succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs).

Over the course of decades, SDHIs have been swiftly developed and extensively employed to combat various plant fungal diseases and manage fungal resistance to other fungicides (Sierotzki and Scalliet 2013; Liet al.2021).Functioning as a pivotal target for fungicides, the mitochondrial SDH complex stands as the sole enzyme complex participating in both the electron transport chain and the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Hensen and Bayley 2011).Comprising of four subunits, namely flavoprotein(Fp; SDHA), iron sulphur protein (Ip; SDHB), and two membrane-anchored proteins (SDHC and SDHD), the SDH complex assumes significant importance (Wanget al.2015a, b).To date, at least 23 SDHI fungicides have been commercialized to effectively combat plant pathogenic fungi (Huaet al.2020; Liet al.2021).SDHIs function by impeding mitochondrial respiration, and mutations in conserved amino acids within different subunits have been linked to SDHI resistance in diverse phytopathogenic fungi(Skinneret al.1998; Hondaet al.2000; Mcgrath and Miazzi 2008; Avenot and Michailides 2010; Wanget al.2015a).

Boscalid, a pioneering broad-spectrum SDHI member,delivers excellent inhibitory effects on filamentous fungi,includingS.sclerotiorum,Botrytiscinerea,Alternaria alternata, and powdery mildews, as well as other fungal pathogens affecting fruits, vegetables and vines(Matheron and Porchas 2004; Stammler and Speakman 2006; Stammleret al.2007b; Wanget al.2009, 2015b).Previous studies have underscored boscalid’s potent hindrance of mycelial growth and conidial germination in numerous fungal species (Mileset al.2013).However,due to the repetitive and frequent application, instances of boscalid-resistant isolates have emerged in different fungal species (Avenotet al.2008; Stammleret al.2011).ForS.sclerotiorum, Glättliet al.(2009) and Stammleret al.(2011) have reported field resistance resulting from the H134R mutation in the SDHD subunit(Glättliet al.2009; Stammleret al.2011).Conversely,Wanget al.(2015a, b) demonstrated that boscalid resistance in laboratory mutants stem from an amino acid mutation, A11V, within the SDHB subunit.Despite its global utilization, the extent of boscalid resistance within theS.sclerotiorumpopulation in asparagus lettuce fields remains largely unexplored.

In this present study, a total of 172S.sclerotiorumisolates were collected from asparagus lettuce field.The objectives encompassed: (i) assessing the current prevalence of boscalid resistance amongS.sclerotiorumisolates within Jiangsu Province, China; (ii) elucidating the biological attributes of the pathogen; (iii) comparing theinvitroefficacy of boscalid between the low-level resistance to boscalid (BosLR) and boscalid-sensitive (BosS)isolates; and (iv) delving into the underlying mechanisms that bestow resistance uponS.sclerotiorumagainst boscalid.These findings not only contribute to SSR control strategies but also enhance our comprehension of boscalid’s mode of action, thereby guiding the development of novel SDHIs in the future.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Fungicides and media

All fungicides used in the current study were technical grades.Boscalid (active ingredient 97.0%), thifluzamide(a.i.98.0%) and fluazinam (a.i.97.0%) were kindly offered by Jiangsu Lanfeng Bio Chemical Co., Ltd.,China; pydiflumetofen (99.0%) was generously provided by Syngenta (China) Investment Co.Ltd.; tebuconazole(98.0%) was obtained from Shenyang Institute of Chemical Technology (Shenyang, China).To create stock solutions, all the aforementioned fungicides were dissolved in methanol at a concentration of 104μg mL-1and stored at 4°C for a maximum period of 2 weeks before being serially diluted for use in this study.Additionally, the potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium, made from 200 g of potato, 20 g of dextrose and 16 g of agar per liter of distilled water, along with the YEPD (w/v, 0.3% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% dextrose) liquid medium, were subjected to sterilization at 121°C for 20 min.

2.2.Isolation of S.sclerotiorum from asparagus lettuce

Infected stems of asparagus lettuce (LactucasativaL.var.angustanaIrish) carrying sclerotia were collected from Changshu, Wuxi, Xuzhou, Xinyi, Yancheng, and Pizhou cities in Jiangsu, during 2019.In order to obtain the isolates, mature sclerotia from independent lettuce were immersed in 1% NaClO solution for 3 min.Following this treatment, the sclerotia were bisected and subsequently washed three times with sterile water.These processed sclerotia segments were then transferred to PDA plates supplemented with 100 μg mL-1of streptomycin sulfate(Solarbio Science& Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing,China).Over a span of 14 days of incubation at 25°C,either a single sclerotium or the mycelia of each isolate were meticulously preserved in fresh PDA slants at 4°C(Stammleret al.2007a).In total, 172 isolates were obtained in this study.

2.3.Sensitivity of the S.sclerotiorum isolates to boscalid

To assess the resistance of these isolates to boscalid, fresh mycelial plugs of each strain (5 mm in diameter) cut from the outer 1/3 margin of 2-day-old colonies were transferred to PDA plates containing 5 μg mL-1of boscalid, a discriminatory concentration established to identify sensitive and resistant strains (Wanget al.2015a, b).The mycelial plugs were oriented with their surfaces facing upwards,and the agent-free PDA plates were used as control (CK).After incubation at 25°C for 2 days, the mycelial growth of each isolate was meticulously observed and the resistance frequency was ascertained (Table 1).Given the substantial number of boscalid-resistant strains that were acquired, a random selection was made of two BosSisolates (CS77S and CS91S) and ten BosLRisolates (CS23R, CS31R,CS117R, CS121R, CS138R, CS141R, CS150R, YC2R,WX7R, and WX12R) for further investigations.The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), which corresponds to the minimum concentration causing complete cessation(100% inhibition) of mycelial growth, was estimated for these twelve isolates against boscalid.Concentrations spanning 0, 5, 10, 50, 100, 200 and 400 μg mL-1were employed for this purpose.Additionally, the effectiveconcentration for 50% growth inhibition (EC50) values of these isolates in response to boscalid were determined based on the concentrations outlined in Table 2.Each treatment was represented by three replicates, and the experiment was independently performed three times.

Table 2 Concentrations of fungicides used to determine crossresistance of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

2.4.Mycelial growth and sclerotial production of S.sclerotiorum

For the evaluation of mycelial growth and sclerotial production among the 12 selected isolates, mycelial plugs(5 mm in diameter) of each strain cut from the outer 1/3 edge of 2-day-old colony were placed on agent-free PDA plates.Following a 2-day incubation period at 25°C,the diameters of the resulting colonies on each plate were measured in two perpendicular directions, and the plates were subsequently photographed.In addition, as a crucial element within the life cycle ofS.sclerotiorum,the formation of sclerotia by the examined strains was meticulously assessed.Subsequent to one month of incubation at 25°C, with each strain’s plate replicated four times, the number and the dry weight of the produced sclerotia on each plate were quantified.All these experiments were conducted three times independently.

2.5.Pathogenicity assay

To access the pathogenicity of the 12S.sclerotiorumisolates on lettuce stems, the surface of lettuce stem was initially disinfected with 75% alcohol, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile water for three times.Subsequently,the air-dried lettuce stems were wounded with sterilized needle and inoculated with mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) from each strain (one plug per stem), and fresh PDA plugs were employed as a control.Following an incubation period of 48 h at a temperature of 25°C,maintained under a 12 h photoperiod and 85% relative humidity, the diameter of each disease lesion was precisely measured at two perpendicular directions andthe lesions were then photographed.For each treatment,four replicates were established, and the experiment was performed three times independently.

2.6.Cross-resistance assay

For the cross-resistance assessment, the EC50values of the 12 isolates to boscalid, pydiflumetofen, thifluzamide,fluazinam and tebuconazole were determined on PDA plates containing serial concentrations as outlined in Table 2.After a 2-day incubation period at 25°C, the colony diameters were measured at two perpendicular directions.The percentages of inhibition were subsequently calculated, and the EC50values were estimated through regression analysis of the probit of the percentage of inhibition against the logarithmic value of fungicide concentrations as described previously (Zhenget al.2013).This experiment was performed three times independently, with each concentration replicated three times.

2.7.Comparison of exopolysaccharide (EPS) contents in BosLR and BosS isolates

For the EPS assay, five mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter)taken from 2-day-old colony of each isolate were introduced into 250 mL triangular flasks containing 100 mL of YEPD medium.After a 36 h incubation period in a rotary shaker at 175 r min-1and maintained at 25°C, two of the four repeats were subjected to boscalid treatment at a final concentration of 1 μg mL-1.Subsequently, the filter liquor was collected after an additional 36 h of cultivation.The EPS of each isolate was precipitated from the corresponding supernatant with three volumes of absolute ethanol and air-dried.Ultimately, the EPS content of each strain was dissolved in deionized water and quantified with a standard curve,following established protocols (Duanet al.2018).Four flasks were prepared for each isolate, and this experiment was repeated three times independently.

2.8.Sensitivity of S.sclerotiorum to various stresses

To evaluate the responses ofS.sclerotiorumisolates to diverse environmental stresses, mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) of each strain taken from the edge of a 2-dayold colony were transferred onto PDA plates without or with the cell membrane-damaging agent SDS (0.05 mg mL-1), osmotic stressors D-sorbitol (1 mol L-1), NaCl(1.2 mol L-1), KCl (1.2 mol L-1), ionic toxic stressor LiCl2(0.1 mol L-1), or the cell wall-damaging agent Congo red(0.3 mg mL-1).The untreated PDA plates served as the control.After 2 days of incubation at 25°C, the diameters of the colonies were measured, and the percentage of inhibition of mycelial radial growth (relative to the growth on untreated control plates) was calculated according to established procedures (Zhenget al.2013).This experiment was independently repeated three times, with each stress condition comprising four replicate plates.

2.9.Cell membrane permeability assay

The effect of boscalid on cell membrane permeability was investigated as described (Houet al.2018).Five mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter), cut from the edge of 2-day-old colonies, were introduced into 100 mL of YEPD liquid medium and subjected to cultivation within a rotary shaker at 25°C, operating at 175 r min-1.Following an incubation period of 36 h, two out of the four replicates of each strain were subjected to boscalid treatment at a final concentration of 1 μg mL-1for another 36 h, while the other two replicates were maintained as controls.Consequent to this treatment period, the mycelia of each treatment were harvested, and filtered in vacuum for 20 min.Subsequently, 0.3 g of mycelia from each sample was suspended within a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing 20 mL of ultrapure water.At intervals of 0, 5,10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, and 180 min, the electrical conductivity of the suspensions was measured with an electrical conductivity meter (CON510 Eutech/Oakton, Singapore).As the final step, the mycelia were boiled for 5 min to determine the final conductivity (Duanet al.2013).The relative conductivity of the mycelia was calculated with the formula: Relative conductivity(%)=Real-time conductivity/Final conductivity×100.This experiment was performed three times independently.

2.10.Oxalic acid production assay

To explore the impact of boscalid on oxalic acid (OA)production by eachS.sclerotiorumisolate, the OA content produced by each strain was quantified with a standard curve as described by Duanet al.(2018).Two BosSisolates and 10 BosLRisolates were used in this study, and five mycelial plugs from the margin of 2-day-old colonies of each isolate were transferred into 100 mL of YEPD medium.Following a 48-h incubation period in a rotary shaker (175 r min-1at 25°C), two of the four replicates for each isolate were treated with boscalid at a final concentration of 1 μg mL-1.After an additional 4 days of incubation, the YEPD liquid medium of each isolate was subjected to filtration and centrifugated at 1 500 r min-1for 10 min, and the OA content in the supernatants was measured at a wavelength of 510 nm using microplate reader (Molecular Devices Versa Max, USA) as described by Duanet al.(2018).There were four replicates for each isolate and the experiment was performed three times independently.

2.11.Control efficacy of boscalid against the BosLR isolates of S.sclerotiorum on radish

In order to assess the inhibitory effect of boscalid on variousS.sclerotiorumisolates, one BosSisolate CS77S and four BosLRisolates CS23R, CS138R, CS141R and YC2R were randomly selected for evaluation according to the protocols as described by Kuanget al.(2011) and Houet al.(2018).Mycelial plugs (5 mm diameter) of each strain, taken from the outer 1/3 margin of 2-dayold colonies, were introduced to the artificially wounded radishes.These radishes were previously subjected to separate sprayings with serial concentrations of boscalid,specifically at concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 μg mL-1.The boscalid stock solution (104μg mL-1)was diluted with water containing 0.1% Tween-20, and each treatment was carefully sprayed until the liquid uniformly covered the surface.After an indoor air-drying period of 24 h, the inoculated radishes were cultivated at 25°C, maintained under a 12 h photoperiod, and at a relative humidity of 85% for 2 days.Subsequent to this incubation period, the size of the lesions was measured at two perpendicular directions.Disease control efficacy was then calculated using the following formula: Disease control efficacy=(Mean lesion diameter of control-Mean lesion diameter of treatment)/Mean lesion diameter of control×100% (Duanet al.2018).Four replications were prepared for each treatment and the experiment was repeated three times independently.

2.12.Cloning and sequencing of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD genes

To clone theSDHB,SDHC, andSDHDgenes of the 10 BosLRisolates and two BosSisolates, fresh mycelia of each strain were harvested from 100 mL YEPD.Genomic DNA was then extracted from the harvested mycelia to serve as a template for PCR as described (Chenet al.2014).With reference to the sequences of theSDHB,SDHC, andSDHDgenes available in the NCBI Genome Database(Gene ID: SDHB, SS1G_04384; SDHC, SS1G_01661; and SDHD, SS1G_06173), three pairs of PCR primers (Appendix A) were designed to amplify the complete sequences of the three genes (SDHB, 963 bp;SDHC, 692 bp; andSDHD,681 bp) in each strain.Subsequently, the PCR products were subjected to commercial sequencing (Sangon Biotech Shanghai Co., Ltd., China), and the resulting sequences were aligned by the BioEdit V7.0.9 software.

2.13.Molecular dockings

To elucidate the molecular interactions and binding affinity between boscalid (Appendix B) and the SDHB protein, the complete amino acid sequences of SDHB from the BosLRand BosSisolates were searched for suitable models from the online platform SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/).Molecular dockings of boscalid to the binding site of SDHB protein from the three resistant genotypes were performed through software SYBYL2.1, with BosSisolates serving as the reference.To model the theoretical three-dimensional structure of SDHB, the crystal structure of SDHB (PDB: 2fbw.1) fromS.cerevisiaewas served as a homologous template.Because this template exhibited 88% coverage and 20.67% sequence identity to the amino acid sequence of SDHB protein fromS.sclerotiorum.The molecular docking process was performed using the SYBYL2.1 software.The energy minimization analysis employed the Tripos force field coupled with Gasteriger-Harsili charges.The molecular conformation of boscalid was established by Sketch Mode and subsequently optimized by the Tripos force field and Gasteriger-Hückel charge.

3.Results

3.1.Isolation of S.sclerotiorum strains and identification of the boscalid resistance

A total of 172S.sclerotiorumstrains were isolated from lettuce in the year 2019, out of which 132 isolates (76.74%)exhibited resistance to boscalid, as determined by the discriminative concentration 5 μg mL-1(Wanget al.2015b).Considering the substantial number of resistant isolates,a random selection was made comprising two BosSand 10 BosLRisolates for the following studies (Table 3).For the BosSisolates, the EC50values were measured at 0.047 and 0.079 μg mL-1, with MIC values remaining below the threshold of 5 μg mL-1.In contrast, the majority of the boscalid-resistant isolates exhibited EC50values ranging from 0.25 to 0.47 μg mL-1, and their MIC values ranged from 5-50 μg mL-1, with the exception of CS141R whose MIC is over 50 μg mL-1(Table 3).The RF values were all less than 10.21 (Table 3), underscoring that theS.sclerotiorumisolates collected from the lettuce field displayed a relatively low level of resistance to boscalid.

Table 3 Sensitivity of BosLR and BosS isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce to boscalid1)

3.2.Mycelial growth, sclerotial production and pathogenicity

The mycelial growth of the 10 BosLRisolates exhibited a notably faster pace compared to the BosSisolate CS91S when cultivated on agent-free PDA plates.However, it is important to note that only three BosLRisolates exhibited a statistically heightened growth rate in comparison to the BosSisolate CS77S (P<0.05) (Fig.1; Table 4).In terms of sclerotia production, most resistant isolates displayed increased sclerotium production than the sensitive isolates, especially the sensitive strain CS91S showed a failure to produce any sclerotia (Fig.1; Table 4).In addition, the pathogenicity of BosLRisolates was found tobe comparable to that of BosSisolates (Fig.2; Table 4).Collectively, these findings indicate that the BosLRisolates showed a slightly higher fitness when compared to the BosSisolates.

Fig.1 Comparison of mycelial growth (A) and sclerotial production(B) between BosS and BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce.S, field-sensitive isolates; R, field-resistant isolates.

Fig.2 Comparison of virulence on lettuce stalk following inoculation with the BosS and BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce.Agar plugs without fungal mycelia were used as negative controls (CK).Disease symptoms were analyzed at 3 days post-inoculation.S, field-sensitive isolates; R, field-resistant isolates.

Table 4 Comparisons among mycelial growth, sclerotial production, and virulence of the BosR and BosS isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce

3.3.Cross-resistance between boscalid and other fungicides in S.sclerotiorum

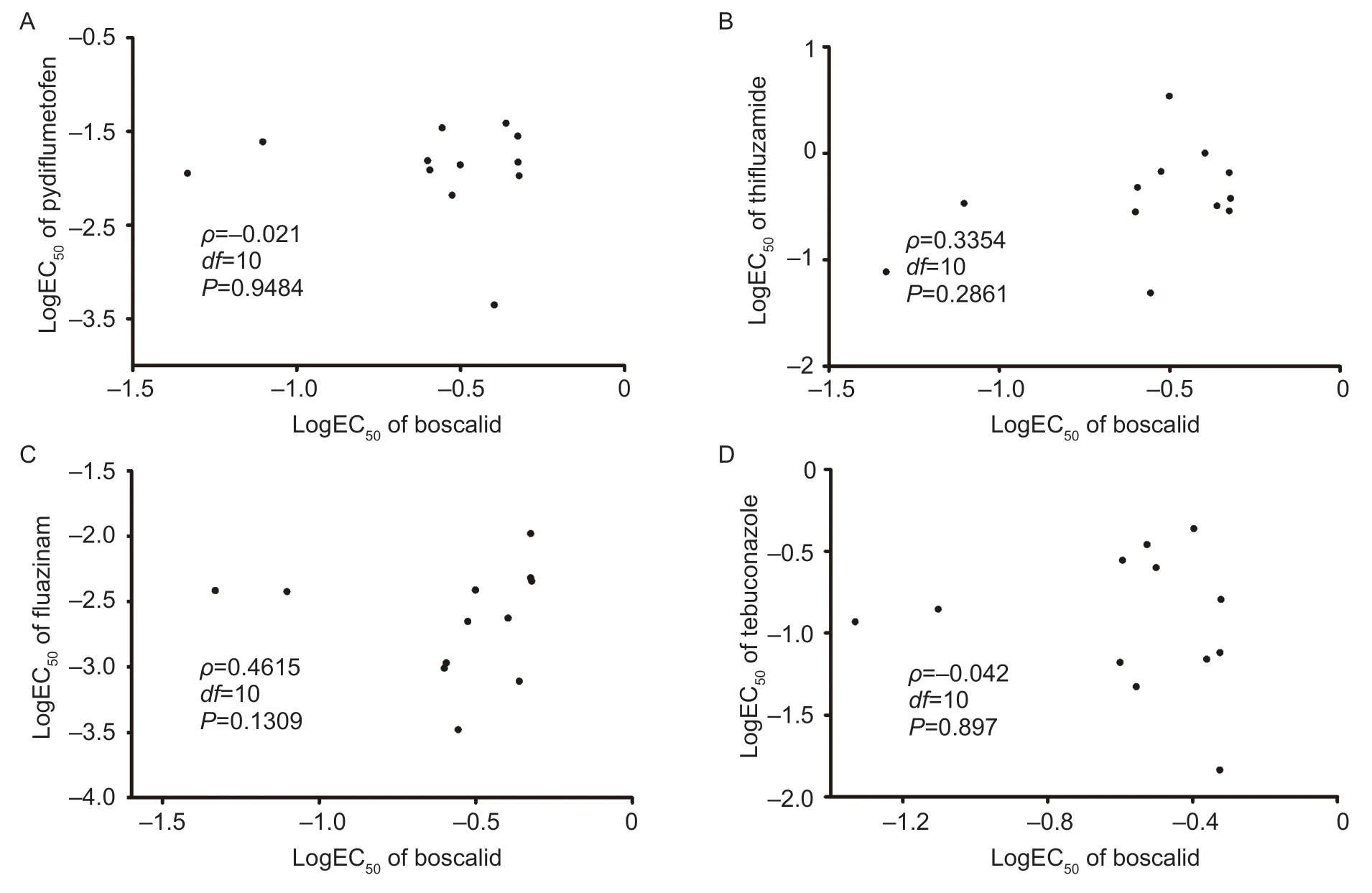

To gain insight into the potential cross-resistance patterns between boscalid and other fungicides, namely thifluzamide, pydiflumetofen, fluazinam and tebuconazole,a comprehensive analysis of the EC50values for the 12 chosen isolates was conducted (Appendix C).Utilizing to Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient as a statistical measure (ρ<0.5,P>0.05), it was determined that no linear relationship was evident between boscalid and the other four tested fungicides (Fig.3).This absence of a discernible liner correlation suggests that no significant cross-resistance phenomena were observed between boscalid and the aforementioned fungicides inS.sclerotiorum.

Fig.3 Cross-resistance determination results of boscalid-resistant and sensitive isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce.Spearman correlation tests for cross-resistance among different fungicides of S.sclerotiorum isolates.Data were logarithmic transformation of EC50 values, or logEC50 for boscalid and those of pydiflumetofen (A), thifluzamide (B), fluazinam (C), and tebuconazole (D).

3.4.Comparison of EPS content of BosLR and BosS isolates of S.sclerotiorum

To examine the EPS content in each strain, the culture of each isolate inoculated in YEPD without or with the treatment of boscalid were collected.Notably, the EPS content of BosLRisolates was observed to be higher than that of the BosSisolates.Upon the application of a 1 μg mL-1boscalid treatment, the EPS content in most isolates experienced a slight reduction, particularly in the case of the BosLRisolates (Fig.4).Such insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of boscalid on EPS production in the context of these isolates.

Fig.4 Comparison of EPS concentration of BosS and BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce.S, fieldsensitive isolates; R, field-resistant isolates.Mean and standard deviations (SD) were calculated from three independent experiments.Values on the bars followed by different letters are statistically different according to the Fisher’s LSD test (the control group P<0.05; the treatment group P<0.01).

3.5.Responses of BosLR and BosS isolates of S.sclerotiorum to multiple stresses

The responses of all isolates to different stress factors exhibited striking variations.When subjected to cell membrane stress induced by 0.05 mg mL-1SDS, the BosLRisolates displayed a decreased sensitivity compared to BosSisolates (Fig.5-A).Concerning osmotic stress,the BosLRisolates showed diminished sensitivity to 1 mol L-1D-sorbitol (Fig.5-B), while the sensitivity to osmotic stress caused by 1.2 mol L-1NaCl or 1.2 mol L-1KCl was comparable to that of the BosSisolates (Fig.5-C and D).Under the treatment of 0.1 mol L-1LiCl, the BosLRisolates exhibited decreased sensitivity in comparison to the BosSisolates.Notably, among the BosLRisolates, CS31R demonstrated a specific decrease in sensitivity to LiCl(Fig.5-E).For stress stemming from cell wall-damaging agents, particularly the stress generated by 0.3 mg mL-1Congo red, the BosLRisolates showed decreased sensitivity compared to the BosSisolates CS77S (Fig.5-F).However, it’s noteworthy that the BosSisolates CS91S exhibited significant decrease in sensitivity to Congo red.These findings highlight the diverse and nuanced responses of the isolates to distinct stress factors,underscoring the complexity of their stress tolerance mechanisms.

3.6.Cell membrane permeability of BosLR and BosS isolates of S.sclerotiorum

Cell membrane is a selectively permeable barrier which regulates the change of substances.However, under adverse conditions, the cell membrane will be damaged and the leaking electrolytes could be determined by electrical conductivity.In this study, most BosLRisolates showed lower relative conductance than that of the control, even under the treatment of 1 μg mL-1boscalid(Fig.6), suggesting that boscalid could lead to the cell membrane damage and increase mycelial electrolyte leakage ofS.sclerotiorum, however, the BosLRstrains exhibited relatively better integrity than the BosSisolates.

Fig.6 Relative conductivity of BosS and BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce treated with 0 μg mL-1 (A) and 1 μg mL-1 boscalid (B).S, field-sensitive isolates; R, field-resistant isolates.Mean and SD were calculated from three independent experiments.

3.7.OA production of BosLR and BosS isolates of S.sclerotiorum

OA, a critical virulence factor ofS.sclerotiorum(Harelet al.2006), was assessed in each isolate, both in the absence and presence of a 1 μg mL-1boscalid treatment.As depicted in Fig.7, all the isolates exhibited no significant difference in OA content within the control group (P<0.05).Intriguingly, when subjected to boscalid treatment, the secretion of OA was significantly inhibited in the BosSisolates in comparison with most of the BosLRisolates (P<0.01).This observation implies that the acquired resistance of BosLRisolates might, in part, be attributed to their sustained OA levels.

Fig.7 The accumulation of oxalate acid of BosS and BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce.S, fieldsensitive isolates; R, field-resistant isolates.Mean and SD were calculated from three independent experiments.Values on the bars followed by different letters are statistically different according to the Fisher’s LSD test (the control group P<0.05;the treatment group P<0.01).

3.8.Control efficacy of boscalid against the BosLR and BosS isolates of S.sclerotiorum on radish in vitro

Thein vitrocontrol efficacy exhibited a positive correlation with increasing boscalid concentrations.In the case of BosSisolates, control efficacy reached 89.59 and 100% when the boscalid concentrations were elevated to 100 and 200 μg mL-1, respectively.Conversely, among BosLRisolates, control efficacy ranged from 76.07 to 90.34% as the boscalid concentration escalated to 200 μg mL-1.Notably, thein vitroefficacy assessment of boscalid underscored a diminished control effectiveness against BosLRisolates ofS.sclerotiorumon radish when juxtaposed with the BosSisolates (Fig.8; Table 5).This finding elucidates the reduced sensitivity of BosLRisolates to boscalid treatment, further highlighting the impact of resistance on the control efficiency of the fungicide.

Fig.8 In vitro control efficacy of boscalid against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on radish.S, field-sensitive isolates;R, field-resistant isolates.

3.9.Cloning and analysis of the SDH gene from the BosLR and BosS isolates

The amino acid sequence of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD consisted of conserved polypeptide chains composed of 301, 189 and 192 amino acid residues, respectively.Upon comparing the sequencing outcomes of theSDHgenes from the BosLRand BosSisolates, it became evident that mutations were localized within the SDHB ard/or SDHC domains from the BosLRisolates.These mutations could be categorized into three distinct resistant genotypes: I, the codon GCA underwent a change to GUA within the SDHB subunit, resulting in the substitution of Ala to Val (SDHBA11V); II, an alteration in the codon sequence was detected in theSDHCgene, where CAG was transformed into CGG, leading to the substitution of Gln with Arg (SDHCQ38R); III, this genotype encompassed a combination of both mutations SDHBA11Vand SDHCQ38R(Table 5).However, no mutation was detected within theSDHgenes of BosLRisolates CS117R and CS141R(Table 6).This comprehensive analysis provides insights into the genetic basis of the boscalid resistance observed in the BosLRisolates, delineating specific alterations within theSDHgenes that potentially underlie their reduced sensitivity to the fungicide.

Control efficacy(%)29.08±2.01 d 52.75±2.77 c 73.17±2.36 b 72.07±1.25 b 90.34±0.76 a YC2R Area per lesion(cm2)4.81±0.10 a 3.80±0.17 b 2.99±0.15 c 2.69±0.15 d 0.33±0.05 e 0.04±0.01 f Control efficacy(%)35.53±2.22 e 56.91±3.54 d 67.67±3.19 c 77.43±0.34 b 79.58±0.42 a CS138R Area per lesion(cm2)4.25±0.27 a 1.77±0.23 b 0.79±0.08 c 0.44±0.06 d 0.22±0.02 e 0.18±0.02 ef Control efficacy(%)27.15±2.08 e 48.65±3.55 d 69.07±3.96 c 78.21±3.12 a 76.07±1.04 ab CS23R Area per lesion(cm2)3.82±0.69 a 2.01±0.25 b 0.99±0.04 c 0.35±0.03 d 0.18±0.02 ef 0.21±0.02 e Table 5 In vitro efficacy of boscalid against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on radish Control efficacy(%)18.05±1.42 e 51.66±0.43 d 69.35±3.59 c 77.32±4.04 b 85.39±0.03 a CS141R Area per lesion(cm2)3.90±0.61 a 2.63±0.50 b 0.91±0.13 c 0.29±0.09 de 0.19±0.04 e 0.08±0.01 f Control efficacy(%)24.24±2.55 e 45.99±0.35 d 67.83±0.45 c 89.59±1.75 b 100 a CS77S Area per lesion(cm2)3.72±0.43 a 2.15±0.39 b 1.08±0.14 c 0.38±0.05 d 0.04±0.01 e 0 f Concentration of boscalid(μg mL-1)0510 50 100 200 Values are mean±SD, which were calculated from three independent experiments.Means in a column followed by the same letters are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test at P<0.05.

Table 6 Mutations at the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunits (succinate dehydrogenase) of the BosLR isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from lettuce

3.10.Molecular dockings

In order to elucidate the mechanism underlying boscalid resistance inS.sclerotiorum, models were established for the docking of boscalid into the binding pocket of the SDHB protein (Fig.9).Notably, the SDHC subunit failed to form a protein-binding pocket suitable for this analysis, our focus was on the SDHB subunit.The amino acid residue involved in the boscalid binding to the SDHB subunit protein of BosLRisolates was identified as ARG246+TYR180, whereas in the cases of BosSisolates,it was ARG246 alone (Fig.9).The docking analysis was complemented by evaluating the docking total score (DTS), which was found to be higher in BosSisolates (1.7499) than BosLRisolates (1.3993).This discrepancy in DTS strongly implies that the SDHB protein of BosLRisolates exhibits a diminished affinity to boscalid when contrasted with the SDHB protein of BosSisolates.These findings collectively provide crucial insights into the potential structural basis underlying the boscalid resistance observed inS.sclerotiorum.

4.Discussion

4.1.The BosLR mutants have been widely selected in the lettuce field

Out of the 172S.sclerotiorumisolates collected from the six cities within Jiangsu Province, a substantial 76.74% exhibited resistance to boscalid.This significant prevalence of boscalid-resistant populations within theS.sclerotiorumspecies underscores the widespread selection of resistance within lettuce fields.In this study, the assessment of resistance levels inS.sclerotiorumisolates was conducted using two key parameters: EC50and MIC values.The BosSisolates exhibited EC50values from 0.047 to 0.079 μg mL-1, with corresponding MIC values remaining below the discriminatory dose of 5 μg mL-1.Conversely, the 10 BosLRisolates displayed EC50values spanning from 0.25 to 0.47 μg mL-1, accompanied by MIC values surpassing the 5 μg mL-1threshold.These results collectively provide compelling evidence for the widespread emergence of boscalid-resistant populations ofS.sclerotiorumwithin the lettuce field environment.

4.2.Most of the BosLR isolates exhibited slightly higher biological fitness

Fitness parameters play a pivotal role in assessing the survival capabilities of field isolates and essential for predicting the efficacy of disease control strategies, particularly those involving fungicide combinations.Prior studies have demonstrated that laboratory-induced boscalid-resistant mutants often exhibit a fitness cost (Wanget al.2015b).Surprisingly, in this study, a contrasting pattern emerged, with the majority of BosLRisolates displaying higher rates of mycelial growth and increased production of sclerotia when compared to theirBosScounterparts.Pathogenicity evaluations revealed no notable variance in lesion sizes between BosLRisolates and BosSisolates when infecting lettuce stems.Furthermore,the comprehensiveinvitroevaluation of boscalid’s control effectiveness against BosLRisolates on radish depicted a pronounced reduction in efficiency when compared to its impact on the BosSisolates.Collectively, these results provide strong evidence that the BosLRisolates ofS.sclerotiorumexhibited heightened biological fitness in comparison to their sensitive counterparts.This enhanced fitness could explain the widespread dissemination of BosLRmutants within field environments.This study’s results underscore the complex dynamics of resistance development and the interplay between resistance mechanisms and fungal fitness, ultimately contributing to the evolution and propagation of resistant populations in natural settings.

4.3.Most of the BosLR mutants showed defects in biochemical responses

The current study sheds light on the potential mechanism underlying boscalid resistance inS.sclerotiorum.The observed increase in cell membrane permeability, coupled with the BosLRisolates’ diverse response to various stressors in comparison to BosSisolates, suggests that boscalid has the capacity to disrupt membrane integrity,leading to mycelial electrolyte leakage.Notably, the response of BosLRisolates to stress factors appears to be altered, highlighting the intricate interplay between boscalid resistance and stress adaptation.Furthermore,the study underscores the significance of OA as a vital virulence factor inS.sclerotiorum, and the secretion of OA might increase the virulence ofS.sclerotiorumin several ways (Duanet al.2013).Previous research has demonstrated that OA-deficient mutants ofS.sclerotiorumare nonpathogenic on host plants and fail to develop sclerotia (Godoyet al.1990).In this study, the observation that boscalid treatment leads to a decrease in both OA and EPS content suggests that the fungicide might inhibit the production of these critical factors.This result indicates that boscalid might lead to the decrease of OA secretion and damage the infection pad inS.sclerotiorum.By elucidating these intricate interactions,this study further underscores the multifaceted impact of boscalid onS.sclerotiorum’s pathogenic mechanisms.

4.4.The amino acid substitute of A11V in SDHB confers the resistance of S.sclerotiorum to boscalid

In the realm of phytopathogenic fungi, the emergence of fungicide resistance predominantly stems from mutations in amino acid residues within target proteins.An array of studies have underscored the pivotal role of mutations within the highly conserved amino acid residues situated in SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD subunits of succinate dehydrogenase in conferring resistance to SDHIs across a spectrum of fungi and bacteria (Wanget al.2015b).Previous study has already elucidated that the point mutation A11V in SDHB, induced under laboratory conditions, and the H134R mutation in SDHD, identified in field mutants, are accountable for bestowing boscalid resistance uponS.sclerotiorum(Glättliet al.2009; Stammleret al.2011; Wanget al.2015a).Nevertheless, our results here showed that some BosLRisolates contained the amino acid mutation A11V in SDHB subunit and molecular docking results revealed that the BosSisolates exhibited a higher affinity for boscalid compared to BosLRisolates.Moreover, a new alteration of Q38R inSDHCgene was found in the field BosLRisolate.Notably, although SDHC subunit failed to form a protein-binding pocket in molecular dockings, the mutation’s role in boscalid resistance cannot be ruled out,especially considering the parallel phenomenon observed in the resistance ofFusariumgraminearumto SDHI fungicide pydiflumetofen (Shaoet al.2022).However,two of the BosLRisolates CS117R and CS141R exhibited no mutation within the SDHB/C/D subunits, suggesting that the resistance ofS.sclerotiorumto boscalid can be caused by other mechanisms.

Additionally, this study diverges from previous finding for theS.sclerotiorumisolates from oilseed rape (Huet al.2018), as it demonstrated that no crossresistance existed between boscalid and thifluzamide,pydiflumetofen, fluazinam or tebuconazole.This insight highlights the potential viability of utilizing these fungicides as alternatives for managing BosR mutants in the field.Based on this comprehensive elucidation, a strategic approach for enhanced efficacy involves incorporating boscalid into fungicidal mixtures featuring diverse modes of action, optimizing the management of SSR on lettuce crops.

5.Conclusion

In this study,S.sclerotiorumisolates collected from lettuce field within Jiangsu Provence exhibited pervasive resistance against boscalid, and the resistant mutants displayed a slightly higher biological fitness compared to the sensitive strains.Among the ten tested BosLRisolates, three resistant genotypes were found, including single point mutation at SDHBA11V, SDHCQ38R, or double point mutations (SDHBA11Vand SDHCQ38R).In addition,the molecular and biochemical profiling of BosLRisolates contributes significantly to our comprehension of the intricate resistance mechanism employed byS.sclerotiorumagainst boscalid.This enriched insight not only advances our knowledge but also holds the potential to inform strategic approaches for managing resistance in the field effectively.The integrated understanding gained from this study paves the way for devising targeted strategies to address the challenge of boscalid resistance inS.sclerotiorum, ultimately benefiting agricultural practices.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development, China (BE2021361), the Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund ((CX(21)2037 and CX(22)3072)), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672065).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.09.024

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年12期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年12期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Biotechnology of α-linolenic acid in oilseed rape (Brassica napus)using FAD2 and FAD3 from chia (Salvia hispanica)

- Analyzing architectural diversity in maize plants using the skeletonimage-based method

- Derivation and validation of soil total and extractable cadmium criteria for safe vegetable production

- Effects of residual plastic film on crop yield and soil fertility in a dryland farming system

- Identifying the critical phosphorus balance for optimizing phosphorus input and regulating soil phosphorus effectiveness in a typical winter wheat-summer maize rotation system in North China

- Characteristics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis serine protease Rv1043c in enzymology and pathogenicity in mice