Association between maternal gestational diabetes and allergic diseases in offspring: a birth cohort study

Yu-Jing Chen · Li-Zi Lin · Zhao-Yan Liu · Xin Wang · Shamshad Karatela,0 · Yu-Xuan Wang · Shan-Shan Peng ·Bi-Bo Jiang · Xiao-Xu Li · Nan Liu · Jin Jing · Li Cai

Abstract Background Previous studies have linked gestational diabetes (GDM) with allergies in offspring.However,the effect of specific glucose metabolism metrics was not well characterized,and the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs),a modifier of metabolism and the immune system,was understudied.We aimed to investigate the association between maternal GDM and allergic diseases in children and the interaction between glucose metabolism and PUFAs on allergic outcomes.Methods This prospective cohort study included 706 mother–child dyads from Guangzhou,China.Maternal GDM was diagnosed via a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT),and dietary PUFAs were assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire.Allergic disease diagnoses and the age of onset were obtained from medical records of children within three years old.Results Approximately 19.4% of women had GDM,and 51.3% of children had any allergic diseases.GDM was positively associated with any allergic diseases (hazard ratio [HR] 1.40;95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.88) and eczema (HR 1.44;95% CI 1.02–1.97).A unit increase in OGTT after two hours (OGTT-2 h) glucose was associated with an 11% (95% CI 2%–21%) higher risk of any allergic diseases and a 17% (95% CI 1–36%) higher risk of food allergy.The positive associations between OGTT-2 h glucose and any allergic diseases were strengthened with decreased dietary a-linolenic acid (ALA)and increased n-6 PUFAs,linoleic acid (LA),LA/ALA ratio,and n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio.Conclusions Maternal GDM was adversely associated with early-life allergic diseases,especially eczema.We were the first to identify OGTT-2 h glucose to be more sensitive in inducing allergy risk and that dietary PUFAs might modify the associations.

Keywords Allergic disease · Cohort study · Eczema · Gestational diabetes · Polyunsaturated fatty acid

Introduction

Allergic diseases are prevalent worldwide and place a substantial health burden on children [1].In China,19.8% of children under two years of age have been diagnosed with allergic diseases [2].Childhood allergic diseases can persist into adulthood [3],severely impact quality of life [4],and increase the risk of other inflammatory diseases and neurobehavioral disorders [5,6].Therefore,understanding the origins of allergies and identifying modifiable risk factors have become important.Pregnancy is recognized as a critical window of susceptibility for the development of allergic diseases,given that the intrauterine environment may alter the programming of the immune response and allergic phenotype [7–9].Some prenatal factors,such as maternal diet[10],tobacco smoke exposure [11],and maternal complications,including gestational diabetes (GDM) [12],have been associated with allergies in offspring.

GDM is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy [13].Pregnant women with GDM present a hyperglycemic intrauterine environment,which can predispose the fetus to oxidative stress,hypoxia,chronic inflammation,and dysregulated immune response [14–16].Epidemiological studies have shown an association between gestational diabetes and childhood allergies [17–21].The pooled estimate from eight studies conducted in Europe and North America showed that maternal diabetes (GDM and pregestational diabetes) may increase the risk of allergic outcomes in children,including asthma,wheezing,and atopic dermatitis [22].Recent cohort studies conducted in the US and Canada also linked GDM with increased risks of wheezing and asthma in early childhood [19,21].However,prior research has shown some limitations,such as using GDM records alone without measuring specific metrics of glucose metabolism,a narrowed focus on allergic outcomes (e.g.,asthma and wheeze),and limited evidence from developing countries.In addition,the role of dietary factors in modifying GDM-related risk of allergies remains unknown.Polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation is a recommended dietary intervention during pregnancy to promote maternal and child health [23],especially n-3 PUFAs,which can enhance insulin function and improve glucose tolerance [24].Our previous studies suggested that PUFAs are not only involved in modulating glucose metabolism [25] but are also related to the development of allergic diseases [26,27].It seems plausible that PUFAs could interact with maternal glucose metabolism via some biological pathways related to inflammation regulation and oxidative stress on the immune system [28,29].Hence,investigating the interactions between dietary PUFAs and maternal glucose metabolism may provide evidence leading to preventive measures toward allergy risk.

The objectives of this birth cohort study were to (1)characterize the associations between maternal GDM and the development of allergic diseases in children under three years of age and (2) explore the interaction between maternal glucose metabolism and dietary PUFAs on allergic outcomes.We hypothesized that the associations between maternal glucose metabolism and allergic diseases may differ with different types of allergic diseases and that dietary PUFAs may have a moderating effect on the associations.

Methods

Study design and population

The study utilized data from a prospective birth cohort in Guangzhou,China (registration number: NCT03023293).We recruited pregnant women at 20–28 weeks of gestation in Yuexiu District Maternal and Child Health Hospital in 2017 and 2018.The eligible women were (1) 20–45 years of age;(2) without pregestational diabetes mellitus,cardiovascular disease,thyroid disease,hematopathy,polycystic ovary syndrome,pregnancy infection,and mental disorder;and (3)singleton pregnancy.At baseline,1035 pregnant women participated in face-to-face interviews,and they were invited for follow-up visits after delivery.This study included 714 children who completed the follow-up at age of three years.We further excluded those who had no information on maternal blood glucose (n=3) and missing data on allergic outcomes(n=5).Finally,a total of 706 participants were included in the study.The detailed study procedures are shown in Supplementary Fig.1.

The ethics committee of the School of Public Health of Sun Yat-sen University approved the study protocol.We obtained written informed consent from all participants at study enrollment.

Assessment of allergic outcomes

Allergic diseases within three years of age were identified based on the parent-provided outpatient medical records and then were further assessed using standardized questions adapted from the International Studies on Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire during the interview with parent [30].We collected the onset age and detailed manifestations of allergic diseases,including eczema,atopic dermatitis (AD),urticaria,allergic rhinitis (AR),allergic conjunctivitis,food allergy,and asthma.Children were considered to have specific allergic diseases if they had a corresponding physician diagnosis and parent-reported allergic symptoms.We defined any allergic diseases as experiencing any of the following diseases: eczema,AD,urticaria,AR,allergic conjunctivitis,food allergy,and asthma.

Among the investigated allergic symptoms,wheezing was determined by the question,“Has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest,but not noisy breathing from the nose?”.

Measurements of plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin

The International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) recommended conducting the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) during the 24–28 gestation weeks for the diagnosis of GDM [13].In clinical practice,Chinese obstetricians and gynecologists may recommend that high-risk women undergo OGTT before 24 weeks.Therefore,pregnant women in this study underwent a standard 75 g OGTT by trained clinical nurses after an overnight fast at 20–28 weeks of gestation (median 25;IQR 24–26 weeks).The plasma glucose levels during OGTT,including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and OGTT after one hour (OGTT-1 h) and OGTT after two hours(OGTT-2 h) glucose,were measured with the glucose oxidase method (ARCHITECT i2000SR;Abbott).GDM was diagnosed if women met at least one of the following criteria recommended by the IADPSG [13]: FPG ≥ 5.10 mmol/L;OGTT-1 h glucose ≥ 10.00 mmol/L;or OGTT-2 h glucose ≥ 8.50 mmol/L.

The glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured in the whole blood sample via the ion-exchange base highperformance liquid chromatography assay method (Variant II,Bio-Rad).HbA1c reflects average glucose levels over the previous 2–3 months [31].

Dietary assessment

The maternal dietary PUFAs in the past month were collected in a face-to-face interview with mothers before OGTT.A validated 81-item quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was administered to assess food consumption based on the reported frequency of each food item and portion size [32].We converted food consumption into daily nutrient intakes (g/day) according to the 2004 Chinese Food Composition Table [33].We also investigated the consumption of nutrient supplements and calculated daily nutrient intakes by adapting the manufacturer’s instructions.Therefore,we quantified dietary intakes of n-3 and n-6 series PUFAs,including a-linolenic acid (ALA),eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA),docosahexaenoic acid (DHA),linoleic acid(LA),arachidonic acid (AA),total n-3 PUFAs,total n-6 PUFAs,LA/ALA ratio,and n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio.

Covariates

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors were collected at the baseline interviews (20–28 weeks of gestation),including maternal age,the highest education level (high school and below,junior college,or university and above),occupation (housewives,administrators and clerks,commerce and services,or others),monthly household income (≤ 6000,6000–12,000,or >12,000 RMB),maternal smoking (yes or no),and alcohol consumption (yes or no).Prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) (kg/m 2) was calculated using the height measured by a standard height measuring instrument (nearest 0.1 cm) and self-reported prepregnancy body weight.Maternal medical complications(i.e.,intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and preeclampsia) were extracted from their medical records,and birth information was obtained from the hospital birth registry system,including the 5-minute Apgar score,child’s sex,parity (1,or ≥ 2),low birth weight (LBW,<2.5 kg),and preterm birth (PTB,<37 weeks of gestation).We also collected children’s postnatal information via parent-reported questionnaires.Exclusive breastfeeding duration (<6,or ≥ 6 months)and the time of introducing solid food (<6,or ≥ 6 months)were investigated at 6 months,and risk factors for allergic diseases such as the family history of allergy (any allergic diseases of parents or grandparents,yes or no) and exposure to second-hand smoke were collected at two years of age.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of participants were reported as the means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.Differences between GDM and non-GDM groups were tested usingttests orχ2 tests.

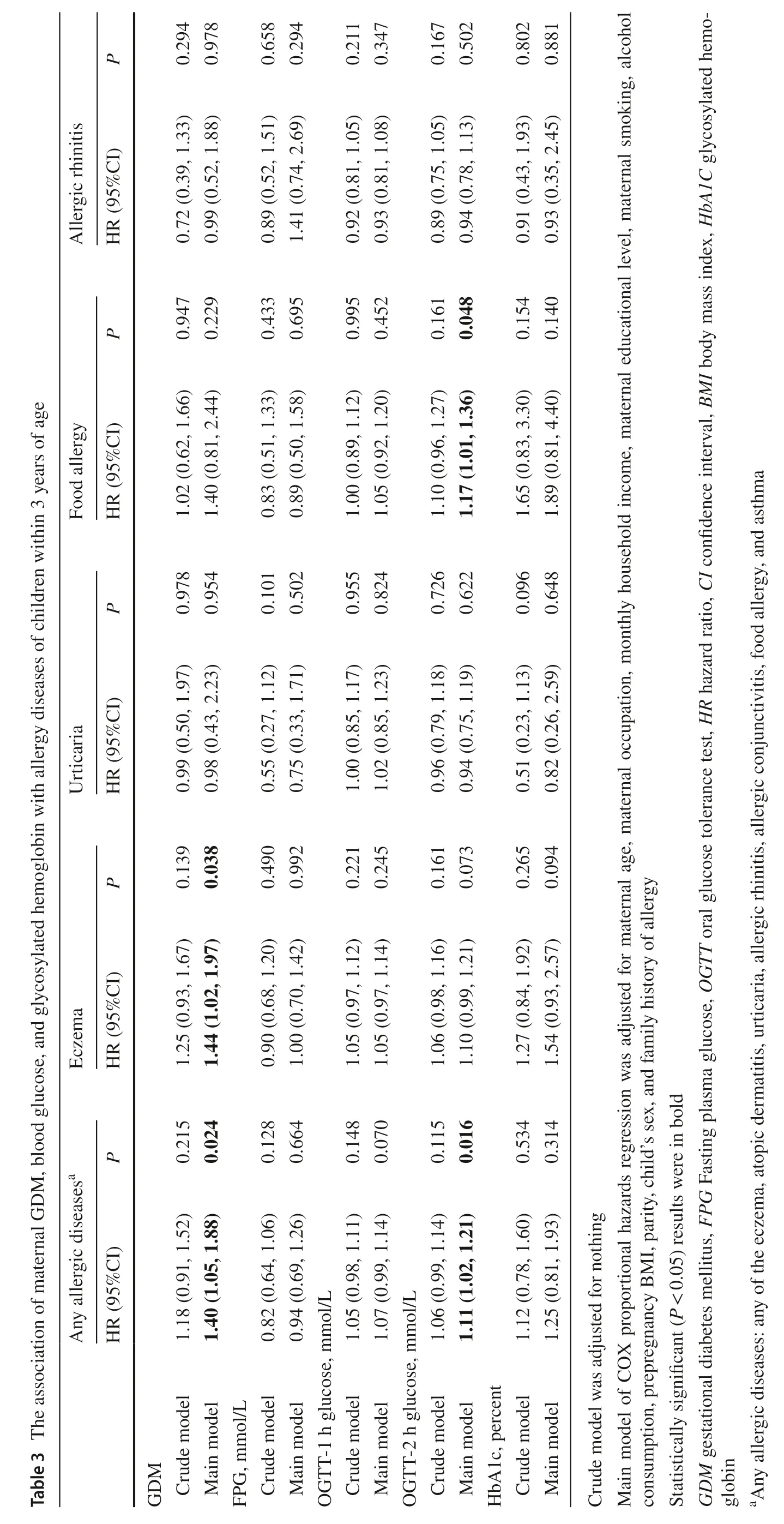

We analyzed the association of GDM,blood glucose,and HbA1c with allergic outcomes by fitting the Cox proportional hazards regression model.Any allergic diseases and four specific allergic diseases (i.e.,eczema,food allergy,urticaria,and AR) with higher incidences in the preliminary analysis were separately analyzed as primary outcomes.The hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented for GDM and per unit increase in glucose biomarkers.The potential confounding factors were identified from the directed acyclic graph (DAG),including maternal age at enrollment,maternal occupation,maternal education level,monthly household income,maternal smoking,alcohol consumption during pregnancy and parity.We further adjusted for the child's sex and family history of allergy in the main analytic model,as suggested by previous studies [12,17,21,37].

The interaction analyses were performed using fully multiplicative models by including the interaction term between glucose biomarkers and continuous PUFA intake in Cox regression if significant associations were found in the main model.We also used the “visreg” package to visualize the interactive effect by delimitating PUFAs into three levels(low as 10th,medium as 50th,and high as 90th).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses: (1) examining the potential influence of birth outcomes (PTB and LBW)and postnatal factors (exclusive breastfeeding,introduction of solid food,second-hand smoke) by adding each of them to the main regression model;(2) categorizing blood glucose and HbA1c into quartiles to investigate whether the association was stronger regarding high-level exposure;(3) considering wheezing as an early sign for asthma and reanalyzing the associations,and (4) total energy intake was included in the interaction model to control for potential confounding dietary factors [34].

All analyses were performed using the statistical software R 4.1.1 (R Core Team,2021).APvalue <0.05 for a twosided test was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of participants

The general characteristics of 706 mother–child dyads are presented in Table 1.Among all included women,19.41% were diagnosed with GDM.Compared to women without GDM,those with GDM were older and more likely to have preterm birth (P<0.05).The total mean (SD) levels of FPG,OGTT-1 h glucose,OGTT-2 h glucose,and HbA1c were 4.42 (0.42) mmol/L,7.79 (1.70) mmol/L,6.77 (1.36)mmol/L,and 5.07 (0.30) percent,respectively.The glucose levels during OGTT and HbA1c were higher in women with GDM than in those without GDM (P<0.05),but they remained similar between children with and without allergic diseases (Supplementary Fig.3).

Table 1 Characteristics of study population (n =706)

Allergic outcomes

Of all children,362 (51.27%) had been diagnosed with one or more allergic diseases before three years of age.The proportion of children with allergic diseases varied from 37.68% for eczema,14.59% for food allergy,and 1.13% for asthma.The incidences of different allergic outcomes by age at diagnosis are shown in Table 2.

Association between maternal glucose metabolism and allergic diseases in offspring

As shown in Table 3,children born to mothers with GDM were at higher risks of any allergic diseases (HR 1.40;95% CI 1.05–1.88) and eczema (HR 1.44;95% CI 1.02–1.97) in the main model.A unit increase in maternal OGTT-2 h glucose was associated with an 11% (95% CI 2%–21%) higher risk of any allergic diseases and a 17% (95% CI 1%–36%) higher risk of food allergy.No associations were found between maternal GDM and glucose levels and allergic rhinitis and urticaria.

Interaction of dietary PUFAs and maternal glucose metabolism

Supplementary Table 1 summarizes maternal dietary PUFA intake during mid-pregnancy.We found a significant interaction between OGTT-2 h glucose and dietary ALA(HR interaction,0.89;95% CI 0.80–0.99;P=0.042),total n-6 PUFAs (HR interaction,1.02;95% CI 1.01–1.04;P=0.008),LA(HRinteraction,1.02;95% CI 1.01–1.04;P=0.006),LA/ALA ratio (HRinteraction,1.01;95% CI 1.00–1.02;P=0.005),and n-6/n-3 PUFAs ratio (HRinteraction,1.01;95% CI 1.00–1.02;P=0.013) on any allergic diseases.The adverse association between OGTT-2 h glucose and any allergic diseases was stronger with decreased ALA intake and increased total n-6 PUFA and LA intake (Fig.1).The association was also strengthened when the LA/ALA ratio and n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio were high.We also observed a similar interactive effect on eczema but not on food allergy (Supplementary Figs.4 and 5).There was no interaction between GDM and PUFAs on allergic outcomes (data not shown).

Sensitivity analyses

The observed associations remained consistent when we additionally adjusted several risk factors for allergic diseases (Supplementary Table 2) and reran the analyses in the subsample of full-term birth or without maternal complications (i.e.,intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and preeclampsia) (data not shown).When examining maternal blood glucose and HbA1c in quartiles,we observed that the highest quartile of OGTT-2 h glucose was associated with a higher risk of any allergic diseases,and HbA1c in the third quartile was associated with a higher risk of food allergy(Supplementary Table 3).We also found that FPG was positively associated with wheezing when comparing the second and third quartiles with the lowest quartile (Supplementary Table 4).

The interaction between PUFAs and OGTT-2 h glucose on any allergic diseases was consistent when total energy intake was adjusted (Supplementary Fig.6).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study conducted in China,we found that children born to mothers with GDM had higher risks of developing any allergic diseases,especially eczema, before three years of age.Maternal OGTT-2 h glucose was positively associated with any allergic diseases and food allergy and had an interaction with dietary PUFAs on any allergic diseases.To the best of our knowledge,this is the first study to show that maternal OGTT-2 h glucose contributes the most to the hyperglycemia-associated risks of allergic diseases in offspring,and we have been the first to identify PUFAs as a dietary modifier in the association.

Previous studies have documented the adverse association between maternal GDM and childhood allergies,while most of them only looked at a few specific allergic outcomes (e.g.,asthma or wheeze) [17,19–21].We provided insights into a broader variety of allergic diseases in early childhood and found that children exposed to maternal GDM had a higher risk of experiencing one or more allergic diseases,especially eczema.Only two previous studies provided evidence of atopic dermatitis (AD,also known as atopic eczema [35]).A Finland national register-based study found that maternal diabetes (composite of GDM and pregestational diabetes)positively predicted the hospitalization of AD by seven years of age [36].The Boston Birth Cohort study also linked GDM to higher odds of AD in 488 term births [37].Corroborating previous findings,our results suggested that GDM may impact allergic inflammatory diseases of the skin.Due to the challenges in diagnosing asthma among preschool children [38],we only performed sensitivity analyses to examine asthma-related wheezing symptoms.Nevertheless,the results of FPG and wheeze were in line with cohort studies conducted in Denmark [20] and Italy [12] that suggested an adverse association between maternal diabetes and childhood wheeze.Future studies should be conducted to investigate whether GDM-related wheezing in early life can develop into asthma later in life.

Our study also carefully examined different indexes of maternal glucose metabolism and identified positive associations of OGTT-2 h glucose with any allergic diseases and food allergy.This novel finding on blood glucose and food allergy may be interpreted by a previous study that found GDM to be associated with a greater risk of sensitization to food allergens (egg,white,milk,peanut,soy,shrimp,wheat,or walnut) [37].A Greek study in 46 Caucasians also observed that children in the GDM group had a higher proportion of atopic profile including food allergy than those in the healthy group [39].In our study,63% of GDM were diagnosed as they had elevated OGTT-2 h glucose level.These results suggested that maternal OGTT-2 h glucose,instead of FPG,accounted for most of the association between GDM and any allergic diseases and was particularly associated with food allergy.Given that the ideal biomarkers to predict GDM and its implications were unascertained[40],our findings highlight the importance of screening OGTT-2 h glucose in terms of reducing allergy risk.

The biological plausibility of these findings is not fully understood,but several potential pathways may be involved.GDM was associated with altered peripheral T-cell profiles and higher total immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels [39],which may consequently skew the immune system toward a helper T cell 2 (Th2)-dominant response and increase the risk of allergic diseases in offspring [41].Moreover,women with GDM exhibit dysregulated cytokine profiles,including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a),leptin,visfatin,and adiponectin [42,43],among which decreased adiponectin has been linked to allergic inflammation [44].Neonates born to diabetic mothers also have increased inflammatory markers correlated with leptins and interleukin (IL)-6 in the cord blood [16],suggesting that maternal inflammation might interfere with fetal immune development.In addition,in the presence of maternal diabetes,insulin resistance and high cord glucose lead to fetal hyperinsulinemia,oxidative stress,and consequent hypoxia [14,15,45],all of which have been hypothesized to influence utero programming of allergies.However,more studies are still needed to further elucidate how epigenetic mechanisms respond to the diabetic intrauterine environment and cause profound effects on the immune system.

Our study suggested that optimizing dietary PUFAs could be one potential way to prevent the hyperglycemia-related risk of allergic diseases.We found an adverse association between OGTT-2 h glucose and allergic diseases,which was strengthened with a decrease in n-3 PUFA (especially ALA)intake and an increase in n-6 PUFA (especially LA) intake.ALA and LA are essential fatty acids that must be obtained through food or supplements,as the human body cannot synthesize them [46].They can be converted into long-chain n-3 and n-6 PUFAs and subsequently function as inflammation resolving or proinflammatory mediators [29].When considering the PUFA intake pattern,we found that highratio ALA/LA and n-6/n-3 PUFAs may work synergistically with OGTT-2 h glucose on allergic diseases,which may be partially explained by the imbalanced PUFA intakes within our study population (with high average n-6/n-3 series PUFA ratio over 20:1).Many studies have suggested that PUFAs have both immunoregulatory and glucose metabolism modulation effects [28,29],supporting the interaction between PUFAs and glucose that we observed in our study.Evidence from clinical trials also demonstrated that lowratio n-6/n-3 PUFA supplementation had obvious effects on lowering inflammation marker levels (i.e.,TNF-α and IL-6)[47] and improving glucose metabolism [48].Our results were aligned with previous studies and further implied that n-3 PUFA supplementation may benefit GDM women regarding allergy prevention in offspring.

Our findings are of public health relevance and of clinical significance.For prenatal care,pregnant women should be educated about the long-term implication of GDM on childhood allergic diseases.Screening and monitoring postprandial glucose and optimizing dietary PUFA intake may be helpful measures in preventing hyperglycemia-related allergies.In pediatric clinical practices,health professionals should detect and manage the high risks of allergic diseases in children born to GDM mothers earlier,especially eczema and food allergy with early onset in infancy.

Several limitations are acknowledged.First,we did not collect immunological indicators and clinical test results for allergy diagnosis of children (e.g.,serum IgE level or skin prick test).Nonetheless,allergic disease diagnoses were identified based on medical records and validated by standardized questions during interviews with parents.Second,due to the low incidences of later developing allergic diseases(e.g.,asthma) among children under three years of age,we could not separately examine these outcomes with sufficient statistical power.Third,unmeasured confounders may bias the results of this observational study.However,a rich set of covariates was taken into consideration,which allowed for adequate adjustments in the associations of interest.Fourth,we did not collect information on all medication use of pregnant women.However,most pregnant women at high risk of treatments were not included in our study.In addition,we collected data on glucose-lowering drug use.There were only four GDM women who had ever used insulin or other drugs to control blood glucose levels during pregnancy.Therefore,we believe that medication use should not bias our results.Fifth,performing OGTT before 24 weeks of gestation may lead to underestimated GDM incidence.However,a small proportion of women with risk factors for hyperglycemia were recommended to undergo OGTT by obstetricians and gynecologists at 20–24 weeks of gestation in our study.We found that those women had a higher prevalence of GDM than the whole study population.Moreover,when excluding those who underwent OGTT before 24 weeks,we observed consistent associations between maternal GDM and allergic diseases in children.Finally,sampling from one central district in Guangzhou may limit the generalization of our findings to other populations and regions.

In conclusion,this prospective birth cohort suggested adverse associations between GDM and allergic diseases,especially eczema,in offspring.When considering different glucose metrics,OGTT-2 h glucose during pregnancy has been shown to be more sensitive in inducing hyperglycemia-related risk of allergic diseases,especially food allergy.Dietary PUFAs might modify the associations and should be further examined as a potential way to prevent early-life allergic diseases in children.

Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/ 10.1007/ s12519-023-00710-0.

AcknowledgementsWe thank all the participating families and the research assistants involved with our study.

Author contributionsLC: conceptualizaion,methodology,investigation,data curation,formal analysis,resource,supervision.YC:conceptualizaion,methodology,investigation,data curation,formal analysis,visualization,writing–original draft.LL: conceptualizaion,methodology,writing–review and editing.SP,BJ,XL,NL: investigation,data curation,formal analysis.YW: visualization.SK,XW,ZL:writing–review and editing.JJ: writing–review and editing,resource,supervision.

FundingThis research was supported by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2019B030335001),the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province,China(2023A1515030192), and the “Nutrition and Care of Maternal &Child Research Fund Project” of Biostime Institute of Nutrition &Care(2021BINCMCF053).

Data availability statementThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy,but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interestNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the School of Public Health,Sun Yat-sen University (approval number:SYSUSPH2021121).Informed consent to participate in the study have been obtained from participants.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年10期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年10期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Sepsis heterogeneity

- How are children with medical complexity being identified in epidemiological studies? A systematic review

- Consensus for criteria of running a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease center using a modified Delphi approach

- Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccines against omicron in children aged 5 to 11 years

- Maternal weight,blood lipids,and the offspring weight trajectories during infancy and early childhood in twin pregnancies

- Determinants of infant behavior and growth in breastfed late preterm and early term infants: a secondary data analysis