Expert elicitations of smallholder agroforestry practices in Seychelles: A SWOT-AHP analysis

Danil ETONGO , Uvicka BRISTOL Trnc Epul EPULE ,Ajith BANDARA, Sanra SINON

a James Michel Blue Economy Research Institute, University of Seychelles, Anse Royale, 1348, Seychelles

b Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Seychelles, Anse Royale, 1348, Seychelles

c International Water Research Institute, Mohammed VI University Polytechnic, Ben Guerir, 43150, Morocco

d Agrifood research and development unit, University of Quebec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), Quebec, J0Z 3B0, Canada

e Department of Computing and Information Systems, University of Seychelles, Anse Royal, 1348, Seychelles

f Department of Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment (MACCE), Victoria, 445, Seychelles

Keywords:Smallholder farmers Agroforestry Climate resilience Extension worker Strengths, weaknesses,opportunities, and threats (SWOT)Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)Seychelles

A B S T R A C T

1.Introduction

Agroforestry is an integrated approach to sustainable land use, as promoted by the International Centre for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF), which has the mandate of leveraging the benefits of trees for human and environment (Nair et al., 2010).Also known as trees on farms, agroforestry is a land management practice in which trees or shrubs are grown around or among crops or pastures (Andreotti et al., 2018).The synergy created by this melange also helps farmers to overcome crop failure due to better nutrient management, more carbon sequestration, and improved land management (Leakey, 2020).Agroforestry offers unique opportunities for livelihood with the potential for poverty alleviation while concomitantly enhancing environmental protection (Nair, 2008).Examples of such opportunities for livelihood include enhancing food and nutritional security and reducing environmental hazards that are characteristics of input-intensive land-use systems (Murthy et al., 2013; Siarudin et al., 2021).The multi-functional character of agroforestry has the potential to concomitantly enhance food and nutrition security, rise income, improve soil health,and mitigate the impacts of climate change (Stainback et al., 2011; FAO, 2018).According to the United Nations Committee on World Food Security (UNCWFS, 2020), agroforestry systems have tremendous potential to contribute to food security, with 1.2 billion people worldwide practicing agroforestry (UNCWFS, 2020; Shukla et al., 2021).

Agroforestry often relies on local knowledge and has increasingly gained recognition in development projects(Jacobi et al., 2017).Local knowledge systems are particularly suitable for resource-limited conditions and lowerinput situations, especially in most developing countries (Nair, 2008), as well as in small island developing states(SIDS) with limited land (van Noordwijk, 2019).Given the limited land mass and the urgent need to augment domestic food production, most SIDS face significant natural resource management challenges which have social,environmental, and economic implications (Etongo et al., 2022).For example, land degradation has an enormous impact on SIDS, hindering their economic growth, human development, and environmental sustainability(Government of Seychelles et al., 2018).Hence, a land use system that simultaneously meets multiple needs, as offered by agroforestry, could address these challenges.The explicit use of trees in agriculture and as part of livelihood strategies is essential to historical human adaptation to small-island conditions (van Noordwijk, 2019).Therefore,forests and trees play a crucial role in strengthening the resilience of food systems, which is essential for Seychelles and other SIDS that depend on food imports.Further, agroforestry is a significant element of climate change mitigation through carbon dioxide emission sequestration (Lawrence and Vandecar, 2015; Zeppetello et al., 2020).

The development of the tourism sector in Seychelles has leaded to about 80% imported food being consumed locally, a condition driven mainly by limited capacity to meet food needs.In parallel, there is a growing interest in locally grown organic food, mainly tropical fruits, by farmers in Seychelles.For instance, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) implemented a two-and-a-half-year agroforestry project in Seychelles as part of its technical cooperation program.The project began in 2016 and aimed to assist the Government of Seychelles in addressing gaps and creating a catalyst for changes in the food production sector (Athanase and Bonnelame, 2016).This pilot project is a continuation of an earlier project implemented by FAO on agroforestry development in Seychelles in 2014 (FAO, 2018).Within the framework of the ‘Ridge to Reef’ (R2R) project and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the government of Seychelles, the FAO, and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) have made significant efforts to develop beneficial agroforestry systems and promote the adoption of organic fruits, vegetables, and livestock among farmers, especially on the three main islands of Seychelles—Mahe,Praslin, and La Digue (UNDP and MEECC, Government of Seychelles, 2019).The R2R project that began in 2020 and would be operational for six years has recorded some progress that can enhance the uptake of agroforestry.Some of these achievements include the production of the Seychelles National Agroforestry Policy in 2021, training on agroforestry for over 80 farmers and 12 extension workers, and technical support for farmers to remove large boulders on their land and create more space for tree planting.

Despite the achievements of the ongoing R2R project, the success of agroforestry depends on several factors,including the availability of preferred tree seedlings, farm size, technical support, land tenure security, the impact on food production and income, access to markets, and modern agroforestry techniques for resource optimization(Stainback et al., 2011; Sereke et al., 2015; Jose, 2019; Oduniyi and Tekana, 2019).For instance, Seychelles has a total land area of 455.0 km2, of which an estimated 50.0% is protected (Ministry of Environment and Energy,Government of Seychelles, 2013).Agricultural land occupies 15.4 km2, representing 3.4% of the country’s land area(Etongo et al., 2022).According to the Seychelles National Agricultural Investment Plan 2015-2020 (Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Government of Seychelles, 2015), 5.0 km2of land are used for agriculture, of which the state owns 3.0 km2, while individuals own 2.0 km2(Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Government of Seychelles,2020).State land is leased to individuals for specific periods, with a minimum lease of ten years (Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Government of Seychelles, 2020).However, a 30-year lease agreement of state-owned land to farmers is one of the provisions in the national agroforestry policy.Other incentives involved in the policies to enhance the uptake of agroforestry in Seychelles include fiscal measures such as subsidized planting materials, access to credits,low tenure fees, and shorter administrative processing times on leased land.

Seychelles has a tropical climate with an annual rainfall that is supposed to be sufficient for rain-fed agriculture(Etongo et al., 2020).However, crop production is often negatively impacted by a prolonged dry season, making the irrigation of farmlands be a common practice in Seychelles.Agroforestry is also constrained by the presence of large boulders on the agricultural landscape, especially on most farmlands in hilly areas, which can potentially reduce the available space for the integration of trees on the farm (Etongo et al., 2022).In Seychelles, a shift from flat to hillside agriculture is expected in the coming decades (FAO, 2017), exposing the area to a decrease in food production and the degradation of forests (Government of Seychelles et al., 2018).Notwithstanding, developing appropriate agroforestry systems that are adapted to local practices and markets in Seychelles is the most appropriate response to counter this projected trend (FAO, 2017; UNDP and MEECC, Government of Seychelles, 2019).In addition,agroforestry can provide a sustainable system of agricultural production based on soil conservation, ensuring food security, improving land use environmental services, and combating invasive species (Andreotti et al., 2018; Jose,2019; Siarudin et al., 2021).For example, research conducted in several Sub-Saharan African countries demonstrates that the inclusion of certain trees into agricultural systems increases crop yields by fixing nitrogen to the soil,sequestering atmospheric carbon, cycling other nutrients, and providing a richer soil organic content (Jamnadass et al., 2011; Coulibaly et al., 2014; Fahmi et al., 2018; Meinhold and Darr, 2021; Tsufac et al., 2021).

Other constraints impacting the agricultural sector in Seychelles and therefore the adoption of agroforestry include limited financial resources, restricted land area, and climate change (Etongo et al, 2022).However, well-structured agroforestry can be an effective strategy to help smallholder farmers leverage the co-benefits of mitigation and adaptation through carbon sequestration (Mbow et al., 2014).For example, research has shown that agroforestry can sequester 1.5-3.5 mg C/(hm2·a) for aboveground carbon in standing biomass (Murthy et al., 2013).Another study in Ethiopia demonstrated that carbon stocks in agroforestry systems ranged from 77.0 to 135.0 mg/hm2(Manaye et al., 2021).The quantity of carbon sequestered in agroforestry systems varies based on tree diversity and their sequestration potential(Negash et al., 2012; Siarudin et al., 2021).Agroforestry can also protect biodiversity by providing a habitat for species that can tolerate a certain amount of disturbance, release pressure on forests, and enhance connectivity among fragmented forest habitats (Jose, 2012; Udawatta et al., 2019).Finally, agroforestry can improve water quality and quantity by decreasing soil erosion and water infiltration and percolation (Sun et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2019; Suprayogo et al., 2020).Seychelles, which faces a lot of land use competition, can benefit from such land management practices.

Some factors influencing the adoption of agroforestry among smallholder farmers in the tropics include access to preferred tree seedlings, farmer resource endowments, socio-demographics, financial incentives, biophysical factors,and uncertainty and risk (Stainback et al., 2011; Ofori et al., 2021).Land tenure security is critical in the adoption of agroforestry, due to the extended period it takes to receive some of the benefits (Kinyili et al., 2020), a phenomenon also echoed by farmers in Seychelles.Due to differing economic, social, and institutional characteristics, factors impacting the adoption of agroforestry by smallholders can vary between countries or regions.Information regarding specific issues on agroforestry in Seychelles can provide valuable insights to policymakers in designing and implementing more effective agroforestry policies and extension services.Knowledge and perception of these factors can enhance the development and adoption of agroforestry systems.

The objective of this study is to co-create strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) factor list of agroforestry followed by a pairwise comparison process that applies analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach among two key stakeholders—extension workers and researchers.Therefore, this study used a consensus approach to arrive at a harmonized and context-specific set of SWOT factors on smallholder agroforestry in Seychelles, complemented by a ranking exercise among extension workers and researchers to tease out their level of importance based on AHP methodology.The AHP method combined the best strategy from various alternative strategies recommended through SWOT matrix.Moreover, AHP is an effective decision-making method, primarily when subjectivity exists.It is suitable in solving problems where the decision criteria can be organized hierarchically (Etongo et al., 2018).

2.Study area and methods

2.1.Study area

The Republic of Seychelles is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean with a land size of 455.0 km2, spreading over 115 islands, and a total population of 96,762 (National Bureau of Statistics, Government of Seychelles, 2018).Situated between latitude 4°-11°S and longitude 46°-56°E (MACCE, Government of Seychelles, 2020), Seychelles lies in the heart of the Indian Ocean off the eastern coast of Africa.The average population density of Seychelles is 182 inhabitants/km2, varying from 1 inhabitant/km2on the Coralline Islands to more than 159 inhabitants/km2on La Digue Island and Praslin Island, and 446 inhabitants/km2on Mahe Island (Government of Seychelles et al., 2012).The climate is wet tropical (equatorial) with slight variations in temperature and relative humidity during the year, the average annual temperature is 27.0°C and the average annual humidity is 80.0%.The weather is dominated by monsoon patterns, with cool winds and little rainfall during the southeast monsoon season (May to October).The southeast monsoon season is the main vegetable growing season.On the other hand, the northwest monsoon between November and April brings variably gentle winds with low clouds and heavy rainfalls.It is a difficult season for vegetable production due to high temperature, rain, and torrential rainstorm (MACCE, Government of Seychelles,2020; Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Government of Seychelles, 2020).Average annual precipitation is 2330.0 mm, varying from 2370.0 mm on Mahe Island to 1990.0 mm on Praslin Island, 1620.0 mm on La Digue Island, and 1290.0 mm on average on the other islands (Etongo et al., 2020).The heaviest rains occurring on the Mahe Island where the central plateau with an altitude of 900.0 m a.s.l.receive up to 3500.0 mm/a, while the south of the island gets less than 1800.0 mm/a (Government of Seychelles et al., 2012).

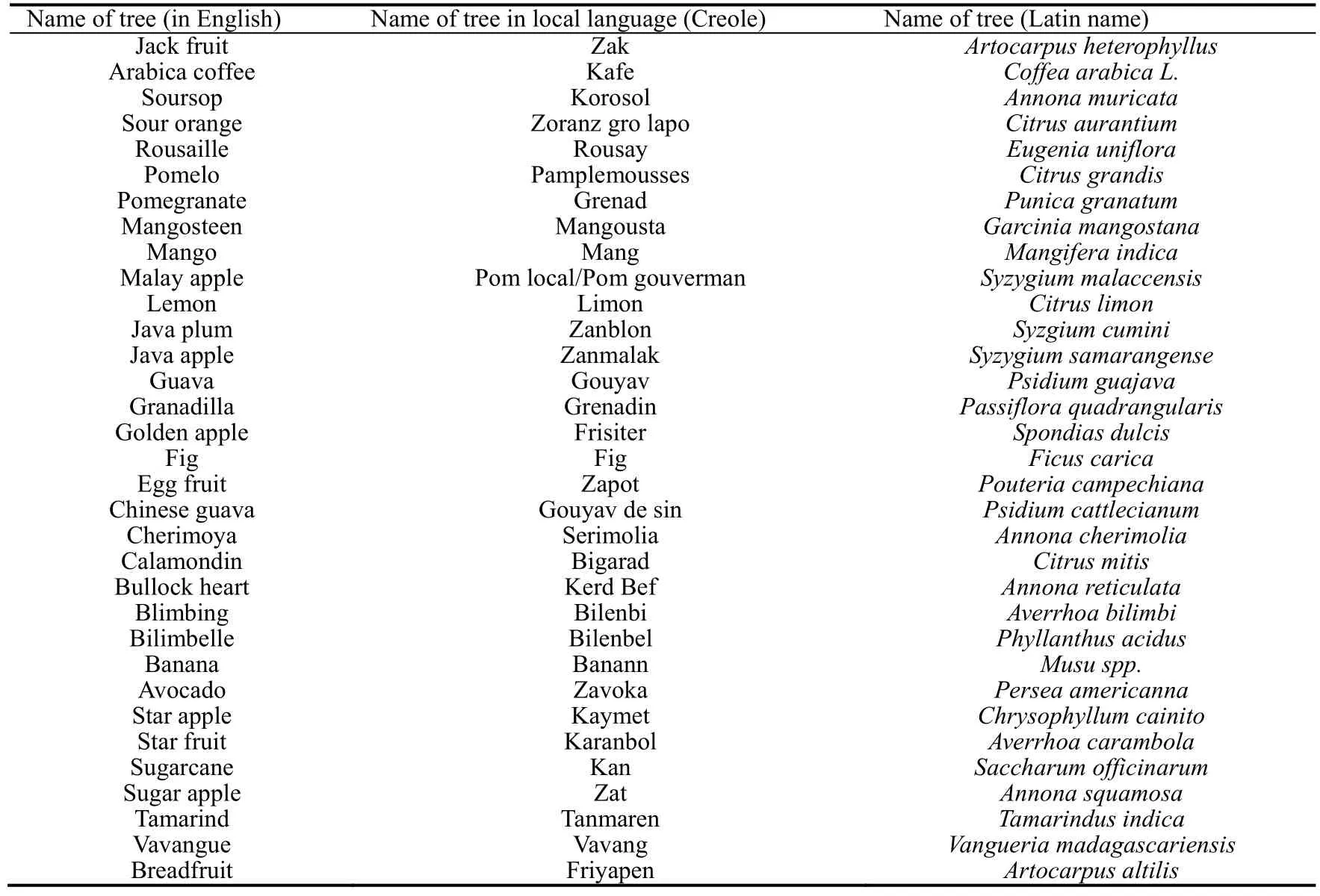

Given that Seychelles is a tropical island, the amount of rainfall is expected to be sufficient to support tree-based interventions such as agroforestry.Agroforestry is not new in Seychelles, and farmers have planted a wide range of fruits and other native tree species for both livelihood benefits and environmental protection.Table S1 shows a list of trees commonly planted by farmers in Seychelles.Though there hasn’t been consensus on the area of agriculture land, an estimated 800.0 hm2of land is the most recent figure from a land use evaluation in Seychelles (Athanase, 2019).Land tenure security in Seychelles falls within two distinct categories that are of state and private ownership, with the former constituting 75.0% and the latter 25.0% (Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture, Government of Seychelles, 2020).Agricultural land faces several challenges and has witnessed severe competition, especially from the tourism sector.On the coastal plateau, there is poor drainage infrastructure with occasional flooding and saltwater intrusion on some farmlands, as identified in a recent study (Etongo et al., 2022).Most farms on sloppy and mountainous terrain are affected by severe soil erosion, especially without effective land management techniques.Two types of soils support the agricultural system in Seychelles.Ferralitic soil, commonly known as “la Terre Rouge” or red soil, originates from the weathering of granitic rocks and extends over the slopes, hills, and mountains of the granitic islands.The other type is calcareous sandy soil found on the small plateaus on the coast of the Granitic Islands and the Coralline Islands (FAO, 2005).

2.2.SWOT-AHP method

In this study, we used an expert focus group discussion based on SWOT technique to identify the strengths,weaknesses, opportunities, and threats involved in adopting a particular strategy—in this case, smallholder agroforestry in Seychelles.This approach highlights the preference of stakeholder, which is crucial in strategic decision-making,especially in Seychelles, where agroforestry has not been sufficiently researched.The strengths and weaknesses are internal indicators (i.e., indicators that directly result from adopting the approach).At the same time, opportunities and threats are external indicators (e.g., market condition, policy environment, etc.) to the situation or intervention.However,the importance of each factor in decision-making cannot be measured quantitatively, making it difficult to assess which factor influences the strategic decision most—a significant limitation of SWOT approach (Pesonen et al., 2001).

Therefore, when combined with AHP, the SWOT can provide a quantitative measure of the importance of each factor in decision-making (Ananda and Herath, 2003).Developed by Saaty (1977), the AHP technique can estimate relative priorities for each factor and category.The AHP method is flexible and enables decision-makers to assign relative importance to each factor through a pair-wise comparison (Etongo et al., 2018).Focus group participants compare factors within and between each category using a predetermined scale (Saaty, 1977).The pairwise comparison implies that applying the SWOT-AHP method is preferable for small sample sizes of individuals or groups that are knowledgeable about the issue under investigation (Ananda and Herath, 2003).

2.3.Implementing the SWOT-AHP method in Seychelles’ case study

Three stages inspired by Kurttila et al.(2000), Stainback et al.(2011), and Etongo et al.(2018) were involved in the implementation of the SWOT-AHP approach in this current study, including the identification of key stakeholders with sound knowledge of agroforestry in Seychelles, the classification of all the critical factors affecting smallholder agroforestry, and the evaluation of the factors among the stakeholder groups guided by the SWOT-AHP framework.

2.3.1.Identification of stakeholders

The entry point for stakeholder identification was a meeting with the Department of Agriculture of Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment (MACCE) on 9 June 2021.During this meeting, which was attended by ten senior staff, the research topic was introduced and the agroforestry experts in Seychelles were identified.These stakeholders include Seychellois government officials and extension workers, and researchers (from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academia, and private consultants) involved in assisting smallholder farmers in adopting agroforestry practices.Identified researchers by this meeting come from the University of Seychelles, R2R project, Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT), Sustainability for Seychelles (S4S),Wildlife Club of Seychelles (WCS), and the Terrestrial Restoration Action Society Seychelles (TRASS).Each stakeholder attended in this meeting knows at least one crucial aspect of agroforestry in Seychelles.For example,during the meeting, it was recommended that all ten agricultural extension workers at the MACCE should be considered as one group.

During the meeting, senior managers at the MACCE agreed that researchers and agricultural extension workers should constitute two groups for SWOT analysis.The selection of participants for the focus group discussion considered their technical expertise in agroforestry, macroeconomic effects, and policies of agroforestry adoption in the context of Seychelles.The decision to consider these two groups aimed at capturing the dynamics related to technical, economic, and policy-related issues that can enhance the uptake of agroforestry in Seychelles.For example,Seychelles just had its first National Agroforestry Policy, which was crafted in 2021 and revised in July 2022 under the leadership of the R2R project team.To ensure the proper gathering of information, all the stakeholders with expertise in agroforestry were grouped into two: researchers and extension workers (including agricultural technicians, policy officers, and adaptation officers).Apart from the initial meeting, a session with each group was organized.Given that another study addresses the factors influencing the adoption of agroforestry in Seychelles among smallholder farmers, farmers were omitted in this study.

2.3.2.Classification of decision factors

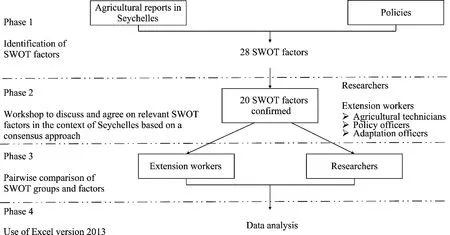

Guided by essential documents on agroforestry in Seychelles and similar studies in Burkina Faso and Rwanda(Stainback et al., 2011; Etongo et al., 2018), a comprehensive literature review was conducted by the authors for the identification of SWOT factors.These documents include (1) the National Food and Nutrition Policy of Seychelles(Government of Seychelles, 2013); (2) policy options on agroforestry—a concept note addressed to the Ministry of Agriculture of Seychelles (FAO, 2016); (3) a report by FAO on developing agroforestry in Seychelles (FAO, 2017);(4) National Agroforestry Policy of Seychelles; and (5) gap analysis report on agricultural land leases in Seychelles(MACCE, Government of Seychelles and UNDP, 2020).A total of 28 SWOT factors were identified from the literature review process.The flow chart presents all the stages of this study (Fig.1).

Fig.1.Schematic of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) -analytic hierarchy process (AHP)process.

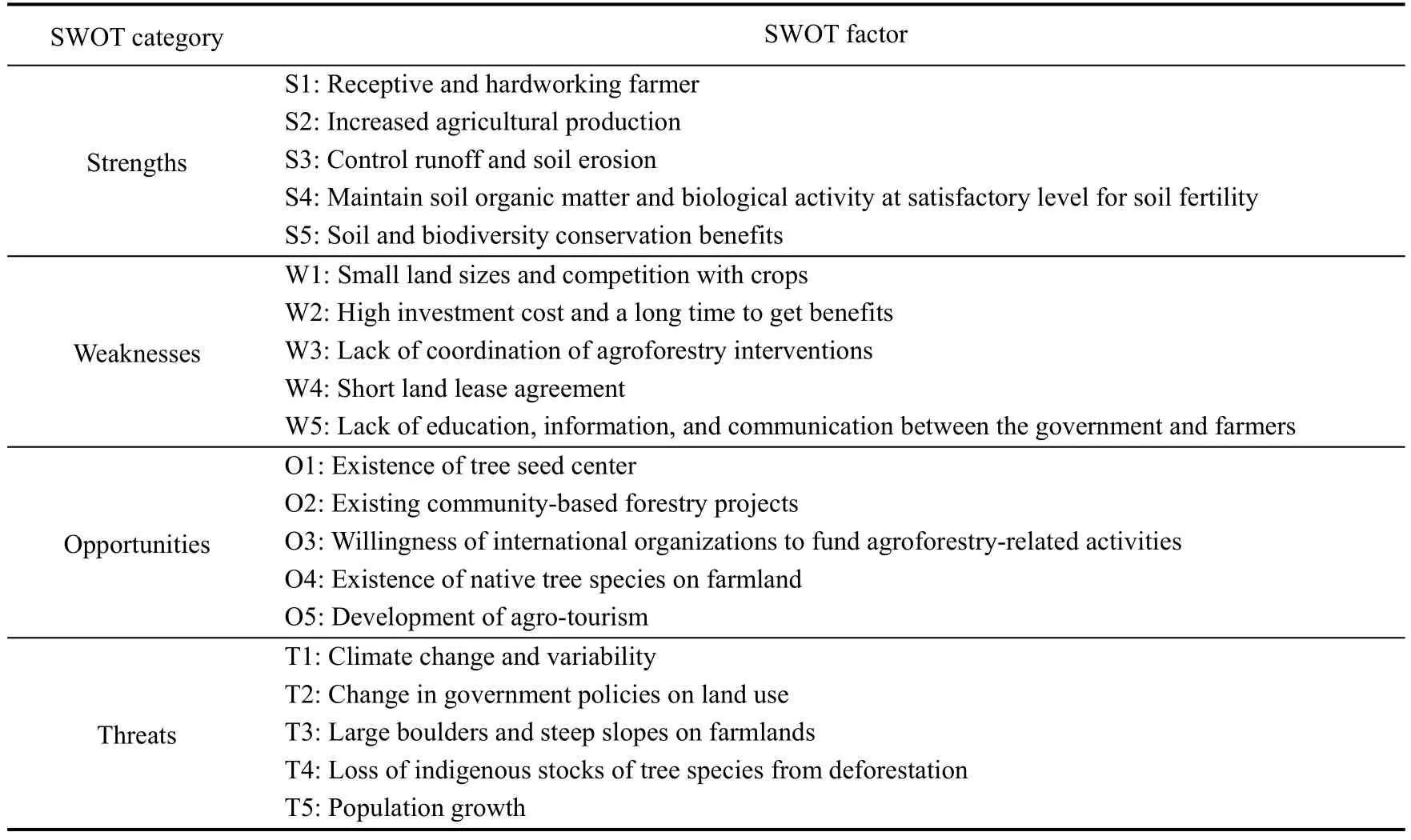

To ensure proper contextualization of SWOT factors or indicators and to arrive at a number that can be manageable,a half-day workshop was conducted on 2 July 2021.The 28 SWOT factors or indicators were presented during the workshop attended by government extension workers and researchers that are active in agroforestry development.The facilitators asked participants to discuss and agree on the SWOT factors to ensure that they reflect the current realities of Seychelles.Based on a consensus, the participants deliberated upon and updated the list of SWOT factors generated from the literature review process.Some similar factors on the initial list were merged and phrased differently.For example, factors such as loss of indigenous stocks of tree species and deforestation as threats to agroforestry were grouped as loss of indigenous stocks of tree species from deforestation and assigned as T4 factor(Table 1).The participants were asked to select the most essential five SWOT factors in each category for pairwise comparison in the next stage.

Table 1The categories and factors of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) approach for agroforestry in Seychelles.

2.3.3.Evaluation of the SWOT factors

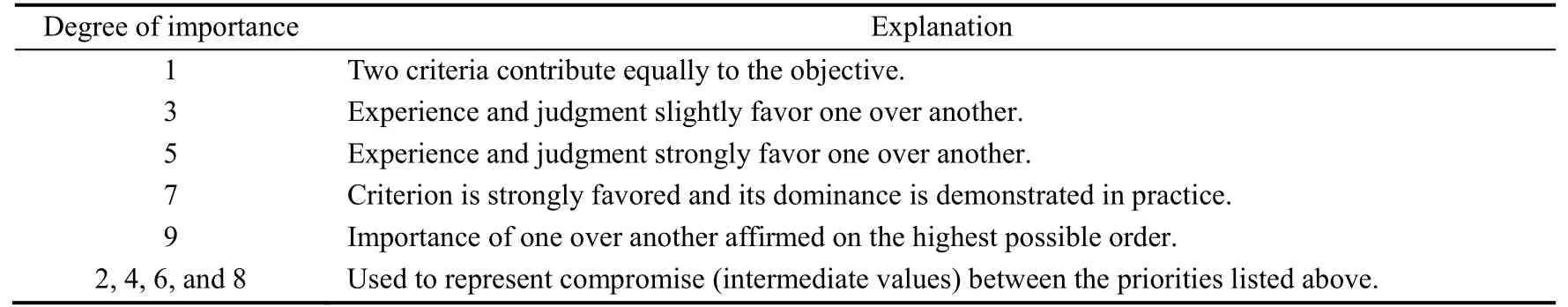

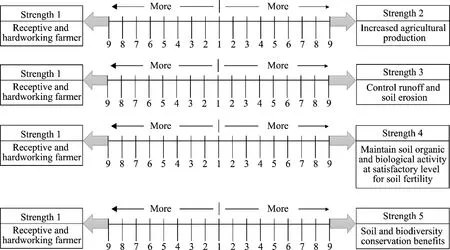

The evaluation of the SWOT factors was conducted separately for both groups.For the researchers, the evaluation took place on 1 October 2021, while that for the agricultural extension workers occurred on 26 October 2021.Each group was presented with the final list of SWOT factors that had been agreed upon.Most participants are familiar with the SWOT factors, so the facilitators provided a brief explanation of the pairwise comparison process to the participants.After explaining the pairwise comparison method, participants could discuss and identify which SWOT factors are more critical.The first step was to compare the four main categories, i.e., strengths, weaknesses,opportunities, and threats based on a 1-9 rating scale (Saaty, 2001; Yüksel and Dağdeviren, 2007).Secondly, factors within each SWOT category were weighted with each other and assigned a value using the 1-9 rating scale (Table 2),as shown in the example of strength factors (Fig.2).

Table 2Pairwise comparison scale with different levels of importance ranging from 1 to 9.

Fig.2.An example questionnaire of pairwise comparison questionnaire.

Kurttila et al.(2000) suggested three steps in conducting a SWOT-AHP analysis.First, the participants need to identify key factors influencing the decision (see Table 1 for a list of factors related to agroforestry in Seychelles).The SWOT factors for each category must be kept below ten to ensure that pairwise comparisons are manageable(Etongo et al., 2018).Second, pairwise comparison of factors within each SWOT category need to be conducted (see Figure 2 for pairwise comparison).The main objective at this stage is to know which factor is more important and by how much based on a scale ranging from 1 to 9 (Saaty, 2001; Yüksel and Dağdeviren, 2007).The prioritization mechanism is accomplished by assigning a number from the comparison scale (Table 2).Pairwise comparisons are conducted separately for each factor, and a priority value for each factor is computed using the eigenvalue method.The factor with the highest priority value under each SWOT category is further compared.Third, the last step is to compare the four categories and calculate a scaling factor for each category.The scaling factors and priority values are used to calculate the overall priority of each factor as follows:

wherejis the priority score of each SWOT category (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats);iis the factor priority score of all factors in each SWOT category; andais the overall priority score of all the SWOT factors.The overall priority score of all factors across these four categories sums to one, and each score indicates the relative importance of each factor in decision-making.

The meaning of each value on the weighting scale of 1-9 was explained by the workshop facilitators to the participants.For example, comparing S1 and S2, if the group response was “5” on the right side, it implies that the“increased agricultural production” factor is five times more important than the “receptive and hardworking farmers”factor.Participants were allowed to deliberate and reach a consensus in assigning a relative weight.The pairwise comparison of SWOT factors with the agricultural extension workers was also conducted on 26 October 2021.Each group continued until all the factors in each SWOT category were exhausted.The consistency ratios were kept within acceptable level (<10.0%), as suggested by two previous studies (Saaty, 1977; Vaidya and Kumar, 2006).

Information derived from pairwise comparisons is represented as a reciprocal matrix of weights, where the assigned relative weight enters the matrix as an elementa, and the reciprocal of the entry 1/agoes to the opposite side of the main diagonal.

where A is the reciprocal matrix;Wis the SWOT factors shown in Table 1 corresponding to S1-S5, W1-W5, O1-O5,and T1-T5, respectively; andnrepresents the last eigenfactor such as S5, W5, O5, and T5.

Multiplied matrix A by the transpose of the vector of weightsw, the resulting vectornwis obtained.

whereIis the identity matrix of sizen(Shrestha et al., 2004).

whereλmaxis the eigenvalue;CI is the consistency index; RI is a random index, generated for a random matrix of sizen; and CR is the consistency ratio (Vaidya and Kumar, 2006).The general rule, which is CR≤0.1, should be maintained for matrix consistency.Homogeneity of factors within each group, and a better understanding of the decision problem can improve the consistency index (Vaidya and Kumar, 2006).Ifλmax=n,the judgments from the pairwise comparison turn out to be consistent.Inconsistency may arise whenλmaxdeviates fromndue to inconsistent responses in pairwise comparisons, therefore, matrix A should be tested for consistency using Equations 5 and 6.

2.4.Data analysis

The data obtained from the two stakeholder groups were analyzed separately using Microsoft Excel version 2013(Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) to derive the local and global priority scores (Table 2).Local priority scores are the relative priorities of the factors in each SWOT category compared with each other.Each category sums up to a value of one.The global priority score represents each category’s relative priority scores, determined by comparing the factors in each category with the highest priority—an analytical procedure standard in SWOT-AHP process(Stainback et al., 2011; Etongo et al., 2018).The other numbers in the global priorities’ columns represent the global priority of each factor determined by multiplying its local importance by the priority of its category.

3.Results and discussion

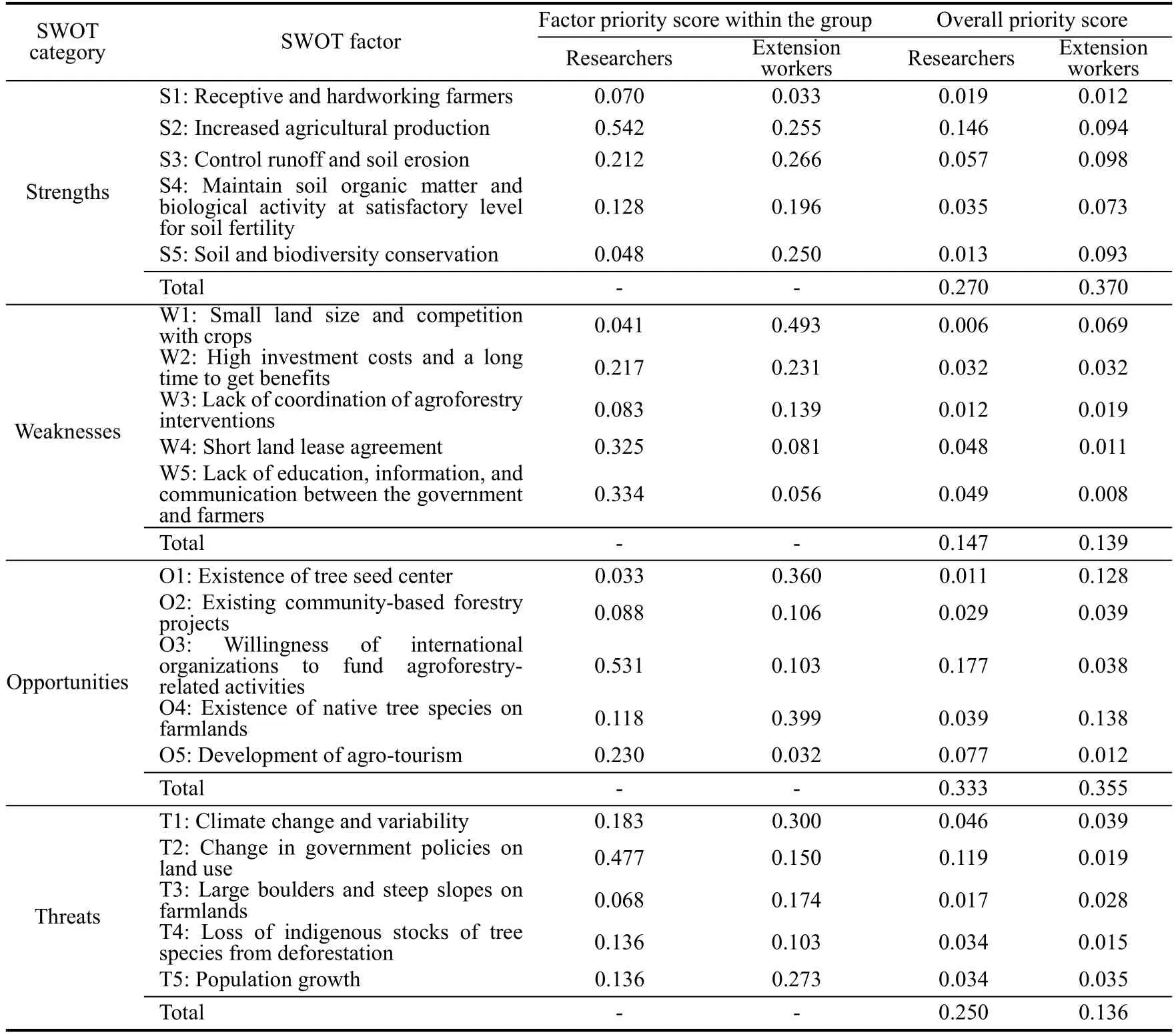

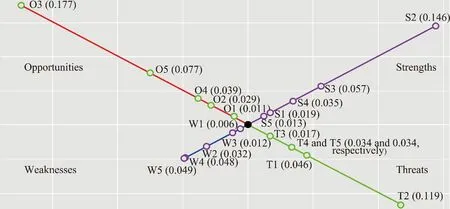

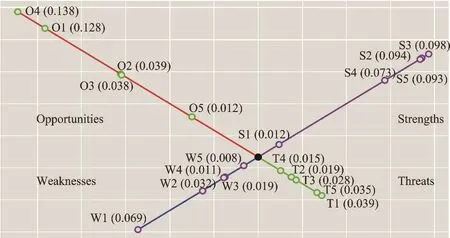

Generally, the two groups agreed on most of the factors and perceived the role of agroforestry as an agent of increased agricultural production in terms of food.Specifically, the positive aspects (strengths and opportunities) are highly rated compared to the negative ones (weaknesses and threats).For example, the combined positive aspects for researchers are 60.3% compared to 39.7% for the negative aspects (Table 3; Fig.3).Similarly, the extension workers prioritize strengths and opportunities at 72.5% compared to 27.5% for weaknesses and threats (Table 3; Fig.4).The results of positive factors from both groups indicated that researchers and extension workers view agroforestry as a suitable strategy for farmers and a land management strategy should be supported government, NGOs, and other stakeholders.The results are presented across the sub-sections of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to understand the differences between the two groups.

Table 3Priority score of each SWOT factor evaluated by researchers and government extension workers.

Fig.3.Overall priority scores of SWOT factors weighted by researchers.S1, receptive and hardworking farmers; S2,increased agricultural production; S3, control runoff and soil erosion; S4, maintain soil organic matter and biological activity at satisfactory level for soil fertility; S5, soil and biodiversity conservation; W1, small land size and competition with crops; W2, high investment costs and a long time to get benefits; W3, lack of coordination of agroforestry interventions; W4, short land lease agreement; W5, lack of education, information, and communication between the government and farmers; O1, existence of tree seed center; O2, existing community-based forestry projects; O3, willingness of international organizations to fund agroforestry-related activities; O4, existence of native tree species on farmlands; O5, development of agro-tourism; T1, climate change and variability; T2, change in government policies on land use; T3, large boulders and steep slopes on farmlands; T4, loss of indigenous stocks of tree species from deforestation; T5, population growth.

Fig.4.Overall priority scores of SWOT factors weighted by extension workers.

3.1.Strengths

The two factors that received the highest rating as strength for both groups are increased agricultural production and the potential for agroforestry to control runoff and soil erosion (Table 3).The factor of increased agricultural production is weighted 54.2% by the researchers.Introducing key tree species on farmlands increases soil fertility and the ability of soil to retain water aside from other benefits (One Earth and World Agroforestry Centre, 2022).The integration of trees within crops enhances and improves soil fertility, and researchers have a better understanding of this strength, especially with impacts emanating from climate change.Temani et al.(2021) found that agroforestry can improve land productivity despite low water availability.Such a strength factor is more critical for Seychelles,where the water retention capacity of soil is partly deficient due to low organic matter (Etongo et al., 2022) and the texture of the predominant red soil (FAO, 2005).Improvement in crop yield under agroforestry systems by enhancing soil fertility has been covered extensively in the literature as a viable option for closing the yield gap in Africa caused by low soil fertility and water stress (Carsan et al., 2014; Amadu et al., 2020; Bado et al., 2021).Additionally,increased agricultural production demonstrates that both the groups understand the multiple benefits of agroforestry and the importance of income generation for farmers.Increased income, according to Ofori et al.(2021), can indirectly lead to an increase in farm productivity as farmers can invest in other agricultural inputs, such as improved seeds.

Regarding the strength factor of agroforestry that can contribute towards runoff and soil erosion control, the extension workers provide a higher weighting than the researchers (Table 3).A plausible explanation for the difference in weighting could be that extension workers visit farmers at least four times a year and have a better understanding of the challenges of those located on flat lands along the coast or sloppy lands on the mountainous terrain.Since most farmlands are on mountainous terrain, erosion is a crucial challenge, especially when farmlands lack trees that can bind soil particles together.The agricultural sector in Seychelles remains vulnerable to climate change and variability and suffers many challenges, such as soil erosion and soil fertility loss (FAO et al., 2019).As far back as 2006, a ten-day training on plant propagation was provided to local tree growers and some farmers in Seychelles by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources in collaboration with the Center for International Corporation of the State of Israel(Seychelles Nation, 2006).Some farmers used the propagation techniques to generate tree stocks for planting, which serves as a windbreak and erosion control for farmers located primarily on sloppy lands (Etongo et al., 2022).A metaanalysis in Sub-Saharan Africa found that agroforestry practices also reduced runoff and soil loss and promoted infiltration rate and soil moisture content, and such benefits are identified at the continental level (Kuyah et al., 2019).

3.2.Weaknesses

Perceived weaknesses for agroforestry show differences between the researchers and the extension workers.Factors of lack of education, information, and communication between the government and farmers (33.4%) and shorter land lease agreement (32.5%) are important to researchers.The two most essential weaknesses are different for the extension workers with weight value of 49.3% for the factor of small plots of farmland and competition with crops and 23.1% for high investment costs and a long time to receive benefits from agroforestry (Table 3).Small land sizes are common challenges for Seychelles, just like most SIDS.During the focus group discussions, the agricultural extension workers concern that most farmers occupy small plots of land.Integrating trees on farmlands means that less land will be available for crop cultivation.Even though growing trees on farmland has a long tradition in Seychelles, the researchers believe that many smallholder farmers lack knowledge of many modern agroforestry techniques.According to the 2020 agricultural strategy of Seychelles, the average farm size is 8000.0 m2(UNDP and MEECC, Government of Seychelles, 2019).However, an earlier report in 2011 had a slightly higher figure of 8782.0 m2(Government of Seychelles, 2011).Another study estimated that 28.0% of farms are below 4000.0 m2, 31.0% between 4000.0 and 8000.0 m2, 33.0% between 8000.0 and 16,000.0 m2, and a minuscule 8.0% of farms above 16,000.0 m2(Seychelles Agricultural Agency, Government of Seychelles, 2016).Though these figures might not differ significantly, most of the farmlands are on mountainous terrain and are dominated by large boulders.The extension workers have an updated list of all the farms in Seychelles, and their regular visit to farmers means they have insights into available land that farmers can cultivate.A study in Seychelles reaffirms that large boulders on farmlands reduce the cultivable area for crops (Etongo et al., 2022).

Factor of lack of education, information, and communication between the government and farmers is rated the highest weakness by researchers, whereas it is the least for extension workers (Table 3).Agroforestry requires specialized skills.Though Seychelles has benefitted from several pieces of training, these trainings have occurred through projects on ad hoc arrangements.Just like in other SIDS, human resource capacity is low in Seychelles.Some of these pieces of training on climate-smart agricultural practices have been provided as part of workshops that often last for less than a week.For example, the ongoing R2R farm project provided a one-week training on approaches to enhance agroforestry development in Seychelles for over 40 farmers in July 2022.The same project provided another training to extension workers, and both groups acknowledged that they learned much about agroforestry.Regarding information and communication, the National Agroforestry Policy that was crafted by the R2R project in 2021 and updated in July 2022 is still to be communicated to the beneficiaries who are farmers.Researchers say this weakness is a common challenge with most policy processes.

Furthermore, researchers also provide a higher rating for weakness factor of shorter land lease agreement when compared to extension workers.The information available to both groups on the lease arrangement of state-owned land is responsible for these differences, and extension workers demonstrate a much better understanding.According to the extension workers, short-term land lease agreements are easily renewed for farmers, and no farmer has been asked to quit state-owned land.However, farmers are only allowed to occupy such land after retirement age on the condition of that another family member takes over the business.The farmer will be asked to vacate the land after retirement without a successor.Such information on land lease arrangements isn’t privy to researchers.It explains the higher rating provided by this group (Table 3; Fig.4).Despite such an insight in the context of Seychelles, with 75.0%of farmers occupying state-owned land, studies showed that insecure land tenure and rights have prevented farmers from long-term investment in agroforestry in most developing countries (Palsaniya et al., 2010; Mugure et al., 2013;Owombo et al., 2015; Benjamin et al., 2021).Therefore, a 30-year land lease agreement will benefit local farmers and be an attractive incentive for investors in the agricultural sector of Seychelles.

Lack of coordination of agroforestry interventions as a weakness shows little difference between the two groups.There is a general sense among the participants that poor coordination or collaboration between different organizations could affect the adoption of agroforestry.The Department of Agriculture of the MACCE is the lead institution on agricultural-related projects and interventions in Seychelles.In some cases, agroforestry interventions are parts of a project through NGOs.While this isn’t a problem, a critical issue is that agroforestry activities occur on ad hoc arrangements based on project tenure, and a framework for continuity ensuring sustainability is lacking.Though many government agencies and NGOs are working in agroforestry, their efforts, according to researchers, are disconnected due to a lack of coordination.Another weakness with a similar rating for both groups is high investment cost and the longer time to reap the benefits from trees on the farm.Many smallholder farmers in Seychelles are faced with immediate sustenance needs.Therefore, they have a very high discount rate, which would value immediate benefits over those that may require several years.

3.3.Opportunities

The two most important opportunities based on the pairwise comparison by researchers include willingness of international organizations to fund agroforestry-related activities and development of agro-tourism (Table 3; Fig.3).International organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), COMESA, GEF, and FAO have previously supported agroforestry activities in Seychelles.The increasing number of agroforestry projects underscores its potential for climate change adaptation and mitigation through enhanced farm biodiversity, soil fertility, and carbon stocks—a view supported by scientific literature (Negash et al., 2012; Maneye et al., 2021; Quandt et al., 2023).Some of this support is in the form of training to farmers, enhancement of the policy environment,provision of materials and equipment, and in some cases, the establishment of agroforestry demonstration farms.Currently, two ongoing agroforestry projects in Seychelles are funded by UNDP.One of the projects is the R2R project,while the other is building a resilient food system by leveraging sustainable agricultural practices.Both projects show the willingness of international organizations to support climate-smart farming practices in Seychelles.The Global Water Partnership Southern Africa (GWPSA) provided funding in 2022 to develop a background paper on the waterenergy-food nexus in Seychelles.One of the commitments of the GWPSA is to identify funding agencies that will finance some of the climate-smart agricultural projects proposed by the MACCE.Given that most agroforestry projects in the past and even now are funded by an international organization, this validates the position as the most important opportunity as perceived by researchers.

Besides the willingness of international organizations to fund agroforestry projects, another factor highly rated in the same SWOT category is the factor of development of agro-tourism.Agro-tourism involves any agriculturally based operation or activity that brings visitors to a farm.The importance of agro-tourism gained traction during the last two decades, especially its potential for local economic development (Rogerson and Rogerson, 2014; Karampela et al., 2016).Seychelles is a great tourism destination for many nationals.The Jardin Du Roi on Mahe Island has been among the best examples of agro-tourism for over four decades.Jardin Du Roi has shown that farming in the island nation can attract tourists to generate revenue for farmers.As such, researchers perceive agricultural land to have alternative uses, and agro-tourism is one of them that can provide a win-win for local livelihoods and environmental protection (Meriton and Bonnelame, 2016).

For the extension workers, the factor of existence of native tree species on farmlands is the most excellent opportunity, and this factor is rated 39.9% (Table 3; Fig.4).Management of native trees in farmlands can enhance genetic diversity in agroforestry systems in Seychelles and elsewhere.Aware of the threats faced by native tree species from invasive and land use change, pieces of training on plant propagation have been provided to farmers by the Department of Agriculture of the MACCE to ensure the sustainability of important tree species.An estimated 15.0 hm2invasive plant species in the Montagne Posee area on Mahe Island has been cleared, while retaining native tree species under the supervision of the Department of Agriculture of the MACCE (Karapetyan, 2020).Some native trees that are kept includeCinnamomum verum(Cinnamon),Artocarpus altilis(Breadfruit), andArtocarpus heterophyllus(Jack fruit).Most farmers in Seychelles believe that agroforestry is suitable for those who live on the mountain occupied with trees and trees grow quickly, rather than those who live along the coast and farmlands are primarily on sandy soils (Etongo, 2023).On-farm tree management is more accessible in this context, and native tree species on the agricultural landscape offer enormous opportunities for agroforestry that cannot be ignored.In the Sahel, due to the regenerative ability, theVitellaria paradoxaandParkia biglobosaare identified as common tree species in agroforestry parklands that have dominated the agricultural landscape for centuries (Ræbild et al., 2012).

Despite the opportunity for the natural regeneration of some indigenous tree species, access to preferred tree seedlings is crucial to farmers.The factor of establishment of tree seed center received the second-highest rating among the extension workers.According to researchers, several tree growing enthusiasts are present in Seychelles,including government agencies, NGOs, and individuals that raise tree stocks in nurseries.The Terrestrial Restoration Action Society Seychelles (TRASS) on Praslin Island and the Department of Agriculture Nursery at Anse Boileau on Mahe Island are two examples.The argument from the viewpoint of extension workers is that establishing a tree seed center will provide easy access to seeds that tree growers can raise in nurseries.This view, according to the extension workers, from an opportunity standpoint hinges on the fact that farmers sometimes do not have access to preferred tree seedlings that they wish to plant because of unavailability in nurseries.An important point raised during discussions with researchers is that agroforestry can provide direct and indirect benefits to farmers and is an opportunity for livelihood improvement and environmental protection.Stainback et al.(2011) echoed similar views that agroforestry can offer indirect benefits to soil productivity over a relatively shorter timeframe, which could partially compensate for some other uses (e.g., fruit and timber) that may take longer to witness.

3.4.Threats

Though the literature has demonstrated that agroforestry interventions have the potential to enhance mitigation and adaptation to climate change (Mbow et al., 2014), this might only be true if such practices are sustainable.The extension workers rank climate change as the highest threat to agroforestry in Seychelles (Table 3; Fig.4).In contrast, it is second highest for researchers (Table 3; Fig.3).In a changing climate, agroforestry species must be able to survive and grow under both current and future climatic conditions.Suppose that tree species integrated into farmlands cannot adapt to future climate.In that case, the risk of that farmers will not achieve the desired functional lifespan of the agroforestry practice is high.Recent studies in Brazil and the West African Sahel demonstrated that climate change threatens ecosystems, including traditional agroforestry systems (Gnonlonfoun et al., 2019; Lima et al., 2022).Climate change and variability could threaten agroforestry as agricultural water experiences variability under different climate scenarios with varied outcomes, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa.The warming in the African continent is projected to be greater than the global average with an increased average temperature of 3°C-4°C by the end of this century (Zewdie, 2014)with considerable variability in rainfall (Niang et al., 2014).While climate projections for rain in West Africa are expected to experience a slight or no change, rainfall in the Eastern and Central African regions is projected to increase(Girvetz et al., 2019).Invasive plants, particularly creepers, pose a severe threat to Seychelles’ biodiversity, withMerremia peltataandDecalobanthus peltatusas typical examples.Climate change has created conditions that enhance the spread of these invasive species in Seychelles (Fleischmann et al., 2020).According to the MACCE, some invasive plant species can secrete chemicals into the soil, making it difficult for any other species to grow where they are located,and implying they can form an entire ecosystem with only a few species (Nicette, 2021).

Change in government policies on land use is a threat factor that receives the highest overall ranking from both groups and stands at 47.7% as weighted by researchers (Table 3).Going by the group of stakeholders, agriculture has lost a lot of land to other land uses, which poses further threats, as competing land uses will intensify amidst population growth.Seychelles, in 2019, initiated a move to put in place a law that will protect agricultural land from being used for other types of development (Athanase, 2019).The proposed law, yet to be formalized, was prompted by the considerable loss of agricultural land to other land uses, estimated at 25,000 hm2during the 1980s and 1990s.Whereas most of these plots of land have been transformed into residential and tourism establishments, a smaller proportion is yet to be developed (Athanase, 2019).In 2011, the Seychelles Agricultural Agency (SAA) indicated that not all 800.0 hm2agricultural land had been put into productive use (Government of Seychelles, 2011).This explains why land for agriculture has been estimated at 500.0 hm2, whereas other sources place the figure at 800.0 hm2.The SAA, in 2019,proposed to the Government of Seychelles to decide what portion of land to be set aside for agriculture and to protect this land through a law.Without such protection, agricultural lands that can boost local food production would suffer the same fate as in the 1980s and 1990s (Athanase, 2019).

Population growth is viewed as a significant obstacle to smallholder agroforestry, which in some cases has led to changes in government policies on land uses.Seychelles is a SIDS with a land area of 455.0 km2(MACCE,Government of Seychelles, 2020), of which almost 50.0% is protected (Ministry of Environment and Energy,Government of Seychelles, 2013).With a growing population, agricultural development, including climate-smart practices, might face intense competition with other land uses such as housing and tourism establishments.The population of Seychelles is expected to grow over the next several decades, encouraging smallholder farmers to devote part of their land to trees will be difficult if land sizes continue to decrease.For farmers, huge boulders and steep slopes further reduce the amount of land available for farming, which poses a threat to population growth—a view supported by Etongo et al.(2022).Large boulders sometimes occupy as much as half of the farmland.Though the large boulders threaten the farming system in Seychelles, they received a lower rating from researchers compared to extension workers (Figs.3 and 4).One possible explanation for the differences could be the role of technology in land management.For example, the ongoing R2R project that provides technical support to farmers willing to remove boulders from their farmlands with the help of tractors and excavators (Government of Seychelles and UNDP, 2020).Additionally, the Local Food Producers Association at Anse a la Mouche on Mahe Island purchased an excavator and a tractor with funding from the UNDP under the GEF small grant program in 2020 (Joubert, 2020).Therefore,researchers have a much better understanding of that the role of technology can mitigate some threats faced by agricultural development in Seychelles.

Factor of loss of indigenous stocks of tree species from deforestation is weighted least by the extension workers during the pairwise comparison of SWOT factors (Table 3; Fig.4).The great antiquity of the granite islands, coupled with their isolation and topography, has created and maintained high endemic biodiversity (Ministry of Environment and Energy, Government of Seychelles, 2013).In the case of Seychelles, deforestation and forest degradation can be traced to two main phases of historical forest loss—commercial logging of timer during 1770-1820 and cinnamon extraction and distillation during 1910-1970s (Kueffer et al., 2013).Though deforestation and forest degradation might have induced a change in the land cover, the extension workers see this threat as the least.The extension workers echo the domestication of most tree species commonly grown on farmlands by the Department of Agriculture,NGOs, and private tree growers as a practice that has existed for several decades.This group further supports their weighting because most farmers have the skills to generate planting materials through grafting.Therefore, indigenous stocks of tree species, including fruit trees, have been preserved from one generation to another despite the historical change in forest cover.The results presented in this study are the perceptions of researchers and extension specialists.The indigenous knowledge and perspectives of farmers that are not investigated in this study offer some opportunities for sustainable uptake of agroforestry.

4.Conclusions

Results of the SWOT-AHP analysis from both groups showed that increased agricultural production is the most potent strength factor, and a favorable political environment is considered as the most significant opportunity.These ratings underscore the importance of agroforestry, which constitutes an environmentally friendly way to provide local fresh foods in SIDS where land is limited.The results also indicated that extension services and coordination of agroforestry interventions need to be improved.More efforts at translating research and expert knowledge can yield substantial benefits to the adoption and implementation agroforestry by smallholder farmers.More sustained valorization of agroforestry is needed to promote its expansion to beneficial levels.For example, the general perception among farmers is that agroforestry is feasible only on farms in Seychelles’ mountainous regions.Such perceptions are borne from the fact that most farmlands on flatlands along the coast consisting of sandy soils cannot support the trees growing quickly on the mountains.Since agroforestry enhances soil carbon, even predominant sandy soils can benefit from this technique over time.

Population growth, on the other hand, is not directly correlated to unsustainable practices but could indirectly affect land management.Achieving food security with a fast-growing population in Seychelles and elsewhere will require efficient and intensive farming techniques.This explains why population growth is considered as a threat to agroforestry,especially among extension workers.Encouraging more effective forms of agriculture, such as agroforestry, may not always be a priority.For example, local farmers increasingly depend on imported synthetic agricultural inputs as the fastest means to augment crop yield.Therefore, education and information sharing by extension workers to farmers regarding different types of agroforestry can improve its adoption.The extension workers are the closest link to the farmers, and ensuring this group has adequate training to support the farmers is crucial.

In sum, agroforestry is seen as a net positive for the Seychellois, which can generate a flow of concrete benefits for farmers and significantly contribute to reducing the carbon footprints associated with food imports.However, it should be noted that the results here reflect the perspectives of researchers and extension specialists with knowledge and interest in Seychelles’ agroforestry.Therefore, the indigenous knowledge and views of farmers that are not investigated in this study offer some opportunities for sustainable uptake of agroforestry.Such a study is pertinent,since socio-demographics, household resources, farm characteristics, and institutional factors including social networks influence the adoption of agricultural technology.For example, differences in soil types on mountainous farmlands compared to those on flat land in Seychelles may mean that the tree species planted are likely not be the same.Since the current study represents the perceptions of researchers and extension specialists, the knowledge gap of farmers is being addressed in other study under the same project.Future agroforestry research in Seychelles should address land suitability analysis of agroforestry and tree diversity and carbon stocks in agroforestry systems.

Authorship contribution statement

Daniel ETONGO: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing -review & editing, and funding acquisition; Uvicka BRISTOL: data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing; Terence Epule EPULE: conceptualization, writing - original draft, and writing - review &editing; Ajith BANDARA: formal analysis, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing; Sandra SINON: data curation, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Review Committee of the University of Seychelles.In addition, the participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Small Grants Program supported this work through the project “Exploring Innovative Opportunities for Promoting Synergies between Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in Seychelles (SEY/SGP/OP6/Y5/CORE/YCC/2019/25), under the youth and climate change portfolio implemented by the University of Seychelles.Special thanks to all the stakeholders who participated in this study.

Appendix

Table S1List of trees commonly grown in agroforestry systems in Seychelles.

- 区域可持续发展(英文)的其它文章

- Measuring the agricultural sustainability of India: An application of Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model

- Impact of taxes on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Evidence from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries

- Geotechnical and GIS-based environmental factors and vulnerability studies of the Okemesi landslide, Nigeria

- Environmental complaint insights through text mining based on the driver, pressure, state, impact, and response (DPSIR)framework: Evidence from an Italian environmental agency

- Examination of the poverty-environmental degradation nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Human-wildlife conflict: A bibliometric analysis during 1991-2023