Proton pump inhibitors and gastroprotection in patients treated with antithrombotic drugs: A cardiologic point of view

Maurizio Giuseppe Abrignani,Alberto Lombardo,Annabella Braschi,Nicolò Renda,Vincenzo Abrignani

Abstract Aspirin,other antiplatelet agents,and anticoagulant drugs are used across a wide spectrum of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.A concomitant proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment is often prescribed in these patients,as gastrointestinal complications are relatively frequent.On the other hand,a potential increased risk of cardiovascular events has been suggested in patients treated with PPIs;in particular,it has been discussed whether these drugs may reduce the cardiovascular protection of clopidogrel,due to pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions through hepatic metabolism.Previously,the concomitant use of clopidogrel and omeprazole or esomeprazole has been discouraged.In contrast,it remains less known whether PPI use may affect the clinical efficacy of ticagrelor and prasugrel,new P2Y12 receptor antagonists.Current guidelines recommend PPI use in combination with antiplatelet treatment in patients with risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding,including advanced age,concurrent use of anticoagulants,steroids,or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.In patients taking oral anticoagulant with risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding,PPIs could be recommended,even if their usefulness deserves further data.H. pylori infection should always be investigated and treated in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease (with or without complication) treated with antithrombotic drugs.The present review summarizes the current knowledge regarding the widespread combined use of platelet inhibitors,anticoagulants,and PPIs,discussing consequent clinical implications.

Key Words: Antithrombotic drugs;Anticoagulants;Aspirin;Clopidogrel;Gastrointestinal bleeding;Proton pump inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs),potent gastric acid secretion antagonists,for treating acid-related disorders,such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcer,as well as for prophylaxis of gastroduodenal lesions in patients treated with acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),has increased rapidly during the last decades;they are now among the most prescribed medications in the world[1-3].

Table 1 Antiplatelet drugs and gastrointestinal bleeding in the real world

The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is noticeable in patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases (CVD) treated with antithrombotic therapy,particularly when different agents are administered together,i.e.,in double antiplatelet therapy (DAPT),or even in triple therapy with DAPT plus oral anticoagulant drugs [vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)].It is still controversial what the risk/benefit ratio is in terms of ischemic/bleeding events in primary prevention with ASA.PPIs are commonly used in patients taking antiplatelet agents and/or anticoagulants and with risk factors to reduce bleeding risk[1-3].In 2009,several reassessments of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data,using platelet aggregation tests as a surrogate endpoint,suggested that PPI treatment might alter the therapeutic efficacy of clopidogrel.The clinical consequence of this interaction,which does not seem a class effect,is controversial.However,after this alert a reduced use of PPIs in patients treated with clopidogrel has been observed,leading to an increase in upper GIB episodes.Possible interactions between aspirin and PPIs have been recently suggested,too.

Table 2 Oral anticoagulant drugs and gastrointestinal bleeding in the real world

Finally,the evidence of cardiovascular risk associated with PPIs,the recent introduction of new antiplatelet agents (such as prasugrel and ticagrelor),the need for long-term DAPT in selected cases,the increasingly frequent indication for anticoagulant therapy,often concomitant with antiplatelet agents,and the introduction of DOACs,stressed the importance of an appropriate preventive PPI prescription.

This review aims to discuss and summarize the current pharmacological and clinical evidence about the widespread combined use of PPIs,platelet inhibitors,and anticoagulants.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK ASSOCIATED WITH PPIs USE

The overall safety of PPIs is considered good,and they are well tolerated.They are,however,highly lipophilic drugs;thus,they may have potential interactions with different pathophysiological pathways involved in immune response,absorption of selected nutrients,infections,cognitive function,bone metabolism,and cardiovascular and kidney morbidity[3].Several studies,in fact,showed concerns about potential risks associated with PPI use,including impaired kidney function,tubular-interstitial nephritis and chronic kidney disease,hypomagnesemia,fractures,infections,nutritional disorders,cognitive impairment and dementia,and even CVD[3].Sehestedet al[4] conducted a study among all registry-Danish population with no prior history of myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke who had an elective upper gastrointestinal endoscopy demonstrating that PPI users,compared with non-users,had a 29% greater adjusted absolute risk of ischemic stroke and a 36% greater risk of MI.In a retrospective nationwide study using a database from Taiwan National Health Insurance[5],patients treated with PPIs had a greater risk of hospitalization for ischemic stroke [hazard ratio (HR): 1.36].People aged <60 years were more susceptible;in contrast,gender,history of MI,diabetes mellitus,arterial hypertension,use of antiplatelet agents or NSAIDs,or type of PPIs had no effect on the risk of stroke[5].PPI treatment was significantly associated with an increased cerebrovascular risk (adjusted odds ratios [ORs] for PPI use: 1.77 within 1e mo,1.65 between 1 and 3 mo,and 1.28 between 3 and 6 mo)[5].Patients treated with PPIs,regardless of the administration of antithrombotic drugs,had a significantly increased cardiovascular risk in a case-control study based on a regional prescriptive database[6].A meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that PPI monotherapy was associated with a 70% increase of CVD[7];furthermore,significantly higher risks of adverse cardiovascular events in the omeprazole subgroup and the long-term treatment subgroup were found[7].Likewise,another recent meta-analysis of 37 observational studies found that the rates of CVD and all-cause mortality were significantly higher among PPI users compared with non-users[8].

In contrast,other studies did not show a significant association between PPI use and CVD.Large American and German administrative claims data failed in demonstrating evidence that risk of MI or stroke was increased after prescription of PPIs compared with H2receptor antagonists (H2RAs)[9,10].Nguyen and colleagues and Lo and colleagues studied sex-different cohorts of women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study and men in the Health Professionals Followup Study,observing non-significant association with new cerebrovascular events[11] and all-cause mortality[12] after adjusting for potential confounders.

A meta-analysis of observational studies showed pooled HRs for association between PPIs and MI,PPIs and acute cardiovascular events,and PPIs and cardiovascular mortality of 1.05,0.99,and 1.06,respectively,after adjusting for bias[13].Finally,another meta-analysis of ten articles did not demonstrate significant differences in risk of all-cause death,major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs),or target vessel revascularization (TVR) between patients treated with PPIs and controls[14].Thus,regarding the association of PPIs with CVD,the results remain inconsistent due to medium to high-risk biases among the pooled studies[15].It is obvious that results may differ greatly among selected population used in each study.Clinical epidemiology evidence from observational data suggests,in fact,that among patients treated with thienopyridines,cardiovascular risk may be increased by long-term use of PPIs[1].In contrast,in patients not treated with thienopyridines,the impact of PPIs on cardiovascular risk is limited by confounding[1].

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS OF CARDIOVASCULAR DAMAGE FROM PPIs

According toin vitrostudies,a potential mechanism explaining the association between PPIs and CVD might be the inhibition of nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide (NO) pathway that results in cardiovascular protective effect.Omeprazole prevents the effects of nitrite and nitrate,which require low pH in the stomach to generate NO and other NO-related species[16-18].

PPIs,besides,may inhibit NO production by inhibiting the enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase,thus increasing levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine,an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial function,implied in vascular cell proliferation,platelet adhesion and aggregation,and inflammation[17-19].

Omeprazole may also reduce endothelium-dependent aortic responses to acetylcholine and increase vascular oxidative stress,which might be associated with endothelial dysfunction by reducing NO bioavailability[20].It is unknown,however,whether impaired vascular redox biology mediated by PPIs may induce endothelial dysfunction,impairment in flow mediated vasodilation,or arterial hypertension[17].

RISK OF GIB AFTER USE OF ANTIPLATELET OR ANTICOAGULATION THERAPY AND CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

In primary or secondary cardiovascular prevention,mainly in the elderly,low-dose aspirin (LDA) is commonly prescribed.Prescribers and consumers,however,do not often appreciate the potential risk of upper GIB associated with LDA use[21].Antiplatelet therapy is,in fact,burdened by a significant risk of GIB,which is increased 1.8-fold during LDA therapy,and up to 7.4-fold with DAPT[22].Treatment with antiplatelet medications,in fact,may cause mucosal lesions (erosions and ulcers),and reduce the formation of the platelet plug on the lesions,thus inducing GIB[23].Therapy with anticoagulants is associated with a higher risk of bleeding,too,although it should be underlined that patients with upper GIB while on long-term anticoagulant therapy had a clinical outcome which is not different from that of patients not taking anticoagulants[24].On the other hand,patients with a major GIB on oral anticoagulants (OACs) had a high rate of discontinuation and significantly higher risk of stroke/systemic embolism,major bleeding,and mortality after hospital discharge than those without[25].Anyway,the combined intake of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents rises the risk of upper GIB by 60%[1,26,27].Thus,the appropriate management of patients treated with these drugs requires an adequate knowledge of risk factors for upper GIB.

The main risk factors predisposing to upper GIB while taking ASA are age >70 years,aspirin dose,concomitant therapy with another antiplatelet agent or NSAIDs,previous peptic ulcer disease,andHelicobacter pylori(H.pylori) infection[1,22,28,29].In the recent ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial,age,smoking,hypertension,chronic kidney disease,and obesity increased bleeding risk in aspirin users[30].In patients withH.pyloriinfection,during therapy with other antiplatelet agents,when compared to ASA,the risk of upper GIB is doubled[31].It is still controversial over the risk associated with alcohol use,smoking,obesity,and systemic comorbidities[1].Finally,the risk of bleeding is often proportional to cardiovascular risk.

The risk factors associated with GIB in VKA users are age >65 years,previous GIB,previous stroke,cardiovascular or chronic kidney disease,and liver cirrhosis[1,26,31-33].The risk of upper GIB is also increased by the concomitant use of lipid-lowering agents,NSAIDs,ASA,and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors[2].

The main risk factors associated with GIB in DOAC users are age >75 years,systemic comorbidities,kidney failure,history of peptic ulcer complicated by bleeding,concomitant use of ASA or NSAIDs,and drug interactions with medications sharing cytochrome P450 metabolism,such as amiodarone,rifampicin,barbiturates,and fluconazole[34-37].In a multicentre retrospective study,concomitant treatment with PPIs was a protective factor;in contrast concomitant treatment with antiplatelet agent or NSAIDs,age ≥ 65 years,alcohol use,abnormal liver function or renal function,cancer,history of peptic ulcer or major bleeding,anaemia,and thrombocytopenia were independent GIB risk factors[38].Using these factors,Lvet al[38] constructed a new model to predict the risk of major GIB in patients on DOACs,the Alfalfa-DOAC-GIB score.

RISK OF GIB WITH ANTIPLATELET AGENTS IN CLINICAL TRIALS

In the meta-analysis of the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration,aspirin increased major GIB (usually defined as a bleed requiring transfusion or resulting in death)[39].In the ASPREE trial,aspirin use increased the risk of GIB in elderly patients by 87%vsplacebo[30].

When LDA is used in association with clopidogrel,or in prolonged antiplatelet treatment,in patients with previous GIB,the incidence of major GIB is even higher[40].The risk of GIB was clearly greater (1.3%vs0.7%) in patients undergoing DAPT (aspirin plus clopidogrel) than in those treated with aspirin alone in the CURE trial[41].Clopidogrel does not act on cyclooxygenase,thus its risk of inducing GIB should be lower than that of aspirin,as demonstrated in the CAPRIE study[42].Therefore,clopidogrel use,particularly in association with PPI,seems a safer monotherapy in patients with recent aspirin-related gastric damage.However,also clopidogrel use seems associated with impaired spontaneous healing of gastric ulcers.In two RCTs enrolling patients in primary prevention with healed ulcer bleeding,comparing clopidogrel with LDA plus 20 mg esomeprazole,the cumulative incidence of recurrent bleeding was significantly higher in the first group[43,44].Therefore,in patients with a previous history of peptic ulcer disease,clopidogrel monotherapy appears questionable[42,43].

Clopidogrel,vice versa,seems safer than ticagrelor,as regards GI-related risks,including fewer overall and spontaneous GIB events[40,45,46].Fewer data are available for prasugrel,compared to ticagrelor and clopidogrel;this drug,however,seems also associated with a significant increase in GIB[40,47].A recent meta-analysis of RCTs showed that third generation P2Y12 inhibitors were associated with a higher risk of upper GIB (32.95%) and unspecified GIB (25.95%) compared to clopidogrel[48].

RISK OF GIB WITH ANTIPLATELET AGENTS IN THE REAL WORD

In RCTs,patients are often different from real world as regards risk factors,clinical characteristics,and comorbidities.Therefore,clinical practice evidence has a fundamental role[26,49-52].Table 1 shows some real world observational studies on this topic[53-57].

RISK OF GIB WITH OAC AGENTS IN CLINICAL TRIALS

OAC therapy (VKAs and DOAC) favours,also,the bleeding of pre-existing lesions (erosions,angiodysplasias,polyps,and diverticula)[58-60].In the RE-LY trial,a higher risk (+50%) of GIB was shown with dabigatran 150 mg bid treatment in comparison to warfarin,while there was no significant difference between dabigatran 110 mg bid and warfarin[53].This increased risk,however,could be attributed to the blind administration of higher dose of dabigatran also in very fragile patients[58].Apost-hocsimulation using the RE-LY dataset,in fact,compared dabigatran,used according to the European label (dose of 150 mg bid only in patients aged <80 years without an increased risk for bleeding,e.g.,HASBLED score <3,and not on concomitant verapamil),compared to well-controlled warfarin treatment [international normalized ratios (INR): 2-3];there was no significant difference between the two medications in terms of major GIB[61].Rivaroxaban was associated with a significantly higher incidence of GIB (3.15%vs2.16%) than warfarin in the ROCKETAF trial,although the frequency of fatal bleeding was comparable[62].In the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 study,the higher dose of edoxaban (60 mg daily) increased (+23%),although barely significantly,the risk of major GIB in comparison to warfarin[63].However,in patients who received the lower dose (30 mg daily),the rate of GI bleeding was significantly lower compared to warfarin[63].Apixaban seems the only DOAC not associated with a GIB increase greater than warfarin[64].The incidence of major GIB,indeed,was comparable between apixaban 5 mg bid and warfarin in the ARISTOTLE trial[64].

A meta-analysis of phase 3 registration studies in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) showed that DOACs increase,although barely significantly,the risk of major GIB by 23%-25% in comparison to warfarin[65].In patients treated with DOACs,in comparison to standard anticoagulant therapy,the overall OR for GIB was 1.45 in another meta-analysis;among the DOACs,only dabigatran (OR: 1.58) and rivaroxaban (OR: 1.48) were associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding[66].In a recent meta-analysis[67] including 28 RCTs,the risk of major GIB for DOACs was equal to that of warfarin;after accounting for dose,rates of major GIB were highervswarfarin (rivaroxaban 20 mg,dabigatran 300 mg,and edoxaban 60 mg daily:+47%,+40%,and+22%,respectively);in contrast,apixaban 5 mg bid was associated with alower rate of major GIB than dabigatran 300 mg and rivaroxaban 20 mg daily.Finally,in another very recent metaanalysis[68] on 37 RCTs,in comparison to conventional therapy,no DOACs increased the risk of major GIB;however,the major GIB risk was different among various DOACs: Apixaban 10 mg daily reduced the major GIB risk more than edoxaban 60 mg,rivaroxaban ≥ 15 mg,and dabigatran etexilate 300 mg.The major GIB risk associated with edoxaban 30 mg daily was lower than that of rivaroxaban 10 mg daily: No differences were observed between apixaban 5 mg,edoxaban 30 mg,and dabigatran etexilate 220 mg.However,there are no RCTs comparing directly the different DOACs.

DOACs,besides,can affect GIB at different sites[59,60].Dabibatran,in 53% of cases,is associated with bleeding events affecting the lower digestive tract[69].The incomplete absorption of the drug in the upper GI tract and the greater availability of dabigatran in the colon,where it would induce bleeding from pre-existing lesions,may be some causes of this phenomenon[59-60].In contrast,rivaroxaban-associated bleeding is more frequent in the upper GI tract;edoxaban 60 mg/d,finally,may cause indifferently upper and lower bleeding[69].Rivaroxaban,being administered once-daily,may cause a higher blood peak of the drug than administration of apixaban and dabigatran administered bid[2,59,64,70].

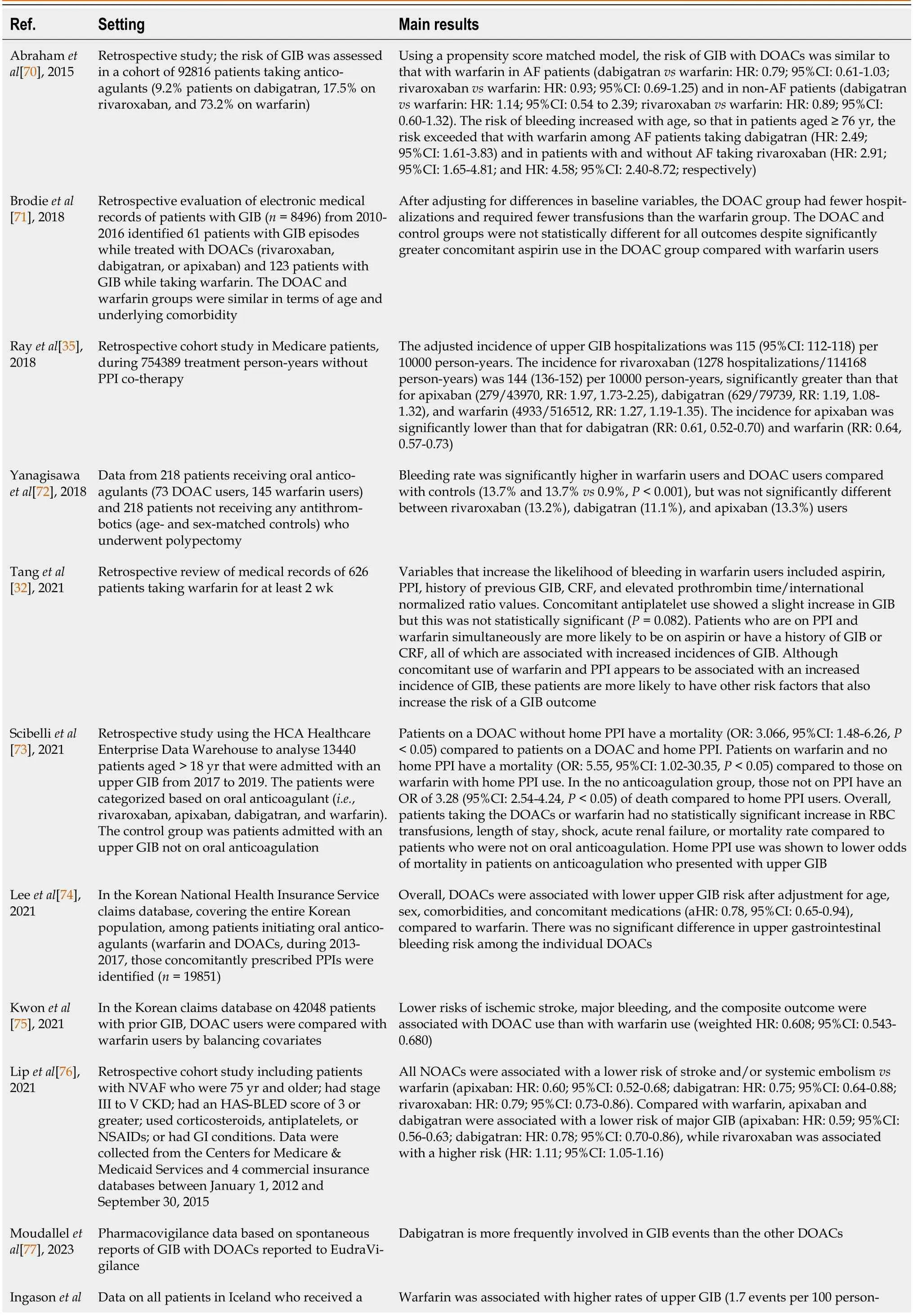

RISK OF GIB WITH ORAL ANTICOAGULANT AGENTS IN THE REAL WORD

The “real world” evidence from observational studies and post-marketing pharmacovigilance data[70-74] shows a different incidence of GIB with some DOACs compared to warfarin (Table 2)[32,35,75-78].

PHARMACOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL INTERACTIONS BETWEEN PPIs AND ANTIPLATELET AGENTS

Several studies have suggested that PPIs may reduce the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel and/or aspirin,possibly leading to cardiovascular events.

Regular PPI use reduced by 90% the likelihood of overt upper GIB in aspirin-users aged ≥ 70 years[79].However,it has recently been reported that long-term use of PPIs can mitigate the anti-aggregating effect of ASA[80].ASA absorption depends on gastric pH,and PPIs decrease gastric acid secretion by blocking the gastric H+/K+-adenosine triphosphataseviacovalent binding to cysteine residues[81,82],but the combination of 30 mg lansoprazole and 100 mg aspirin does not cause a decrease in antiaggregant activity evaluated by the impedance aggregometry method[83].

In 2009,in patients treated with both clopidogrel and PPIs,an increased risk (+40%) of recurrent MI has been reported[84].It was hypothesized that several PPIs,inhibiting the cytochrome P4502C19 (CYP2C19) that transforms clopidogrel into its active metabolites,might reduce its effect[85].After this study,the clinical implications of potential interactions between PPIs and clopidogrel have been debated,with conflicting results,for over a decade.In a Swedish nationwide cohort study including 99836 patients who received clopidogrel after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),compared to non-users,PPI users had increased adjusted HRs of the main outcome MI (+23%) and the secondary outcomes coronary heart disease (+28%),stroke (+21%),and death due to coronary heart disease (+52%)[86].In 947 patients at high risk of upper GIB following aspirin-related bleeding for secondary MACE prevention,compared with aspirin treatment,clopidogrel showed an increased risk of MACEs (+65%),any cause of mortality (+4.8%),and upper GIB (+25%),but without statistical significance in propensity score-matched cohort analysis[87].Using the National Health Insurance Research Database to conduct a retrospective cohort study on patients with diabetes treated with clopidogrel after bare-metal stent deployment,Leeet al[88] showed that patients who received PPIs had no significant increase in adverse cardiovascular events compared to those without PPIs within 1 year (-40%).In a nested case-control study conducted within the Cerner Corporation’s Health Facts®database,adjusted OR for PPI usevsnon-use among clopidogrel users was not significant: A positive association between combined use of clopidogrel/PPIs and increased risk of MI was seen only in the group aged 80-89 years (+26%)[89].Intermittent use of PPIs,compared with sustained use,was associated with lower risks of stroke,MACEs,and net adverse clinical events in a retrospective study on patients with coronary heart disease treated with clopidogrel for at least 1 year[90].

Indeed,the data of meta-analyses were conflicting,too.An increased incidence (+39%) of MACEs,stent thrombosis,and MI in patients taking clopidogrel and PPIs was confirmed by Bundhunet al[91],but not by Cardosoet al[92].A metaanalysis by Moet al[93],evaluating ten RCTs,showed that PPIs decreased the risk of LDA-associated upper GI ulcers (-84%) and bleeding (-73%) compared with control.For patients treated with DAPT (LDA and clopidogrel),PPIs were able to prevent the LDA-associated GI bleeding (-64%) without increasing the risk of MACEs.Panget al[94] included 15 RCTs in their meta-analysis,showing that in patients treated with clopidogrel,the risk of MACEs (-18%),MI recurrence (-28%),stroke (-28%),stent thrombosis (-29%),and TVR (-23%) was significantly lower in the non-PPI group than in the added PPI group.The risks of all cause death,cardiovascular death,and bleeding events were similar in the two groups[94].Another meta-analysis of three RCTs and four cohort studies showed that,overall,there was a significantly lower risk of GIB events in the PPI group compared to the no PPI group (OR: 3.06)[95];in three RCT studies,there was also a significantly lower risk of GIB events in the PPI group compared to the no PPI group.Overall,there was no significant difference in MACE events between the PPI group and the no PPI group[95].

Besides,action of PPIs on CYP2C19 is not class-specific[96].Omeprazole and esomeprazole seem having a more marked inhibiting effect on CYP2C19 than pantoprazole[97].Random-effects meta-analyses of six studies comparing the safety of individual PPIs in patients with coronary artery disease taking clopidogrel revealed,in contrast,an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events for those taking pantoprazole (HR: 1.38),lansoprazole (HR: 1.29),or esomeprazole (HR: 1.27) compared with patients on no PPI;this association,in contrast,was not significant for omeprazole[15].

The COGENT trial was the only prospective study in this field.It showed,in patients at high risk,that omeprazole significantly reduces composite GI events,without observing any increase in the composite cardiovascular events[98].The trial was terminated,however,prematurely;therefore,the absence of interaction between omeprazole and clopidogrel could not be considered as a definitive finding.

The P2Y12 receptor inhibitor Ticagrelor does not require biotransformation;thus,no drug interactions with PPIs may be assumed.Surprisingly,in the PLATO study,MACEs were equally higher both with ticagrelor and with clopidogrel among patients treated with PPIs[99];for this reason,it was hypothesized that treatment with PPIs should be considered as a marker rather than a cause of MACEs.In the Netherlands,an observational registry on patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) treated with PPIs,showed a reduction in cardiac death or MI (adjusted HR: 0.27) and cardiac death,MI,or stroke (adjusted HR: 0.33),but this was not observed in subgroup analyses in clopidogrel-or ticagrelor-treated patients.Besides,treatment with PPIs was not associated with a reduction of GIB[100].In patients undergoing PCI after ACS and receiving clopidogrel or ticagrelor,an international multicentre registry showed no association between PPI treatment and the primary composite endpoint (total mortality,reinfarction,and severe bleeding)[101];patients treated with PPIs were more often female,older,and with more comorbidities.In a single-center prospective sub-study of a randomized trial on 231 patients completing 1-year antiplatelet therapy after coronary aortic bypass graft (CABG),severeupper GI mucosal lesions were more frequently observed in patients treated with ticagrelor plus aspirin and aspirin monotherapy than in patients treated with ticagrelor monotherapy[102].In a prospective study[103],patients with acute MI who underwent PCI and treated with ticagrelor were divided into four groups: Pantoprazole,omeprazole,ranitidine,and no gastroprotective treatment.No significant differences were found in infarction related artery perfusion indexes,incidence of stent thrombosis,platelet indicators,platelet activation and aggregation,myocardial necrosis biomarkers and brain natriuretic peptide levels,and incidence of ischemic endpoint events and other tissue and organ bleeding events[103].A sub-analysis of the randomized GLOBAL LEADERS trial[104] compared the experimental antiplatelet arm (23-mo ticagrelor monotherapy following 1-mo DAPT) with the reference arm (12-mo aspirin monotherapy following 12-mo DAPT) after PCI.In the reference group,the use of PPIs was independently associated with Patient Oriented Composite Endpoints (POCEs: All-cause mortality,MI,stroke,or repeat revascularization;HR: 1.27) and its individual components,whereas it was not in the experimental arm.Thus,in contrast to conventional antiplatelet strategy,there is no evidence suggesting the interaction between ticagrelor monotherapy and PPIs on increased cardiovascular events[104].

Prasugrel,like clopidogrel,is transformed by CYP2C19 into active metabolites,too[85].However,a lower incidence of MI has been observed in patients treated with PPIs and prasugrel (HR: 0.61) compared to clopidogrel[105].No associations with MI were observed for PPI usevsnon-use among prasugrel or ticagrelor users[89].

A meta-analysis[81] including four RCTs and eight controlled observational studies reviewed clinical outcomes in patients taking DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel,with and without concomitant PPIs;overall,patients taking PPIs had statistical differences in MACE (OR: 1.17),GIB (OR: 0.58),stent thrombosis (OR: 1.30),and revascularization (OR: 1.20),compared with those not taking PPIs.There were no significant differences in MI,cardiogenic death,or all-cause mortality[81].Another meta-analysis[106] from 40 studies found no association between the risk of adverse clinical outcomes and the combination of PPI and DAPT in patients with coronary heart disease based on the RCT data.In contrast,observational studies showed an increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes due to the use of PPIs in patients treated with DAPT (risk ratio: 1.26),although the heterogeneity of these studies was high[106].The running “Proton Pump Inhibitor Preventing Upper Gastrointestinal Injury in Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after CABG” (DACAB-GI-2) study will assess the rate of gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers evaluated by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in subjects on DAPT (clopidogrel plus aspirin or ticagrelor plus aspirin) for 12 mo immediately after CABG randomized to either a 12-mo pantoprazole treatment arm or a 1-mo treatment arm[107].

A prospective population-based cohort study[108] of patients with transient ischemic attacks (TIA),ischaemic stroke,and MI treated with antiplatelet drugs,evaluated hospital care costs associated with bleed management during 10-year follow-up.In secondary prevention with aspirin-based antiplatelet treatment without routine PPI use,the long-term costs of upper GIB at age ≥ 75 years are much higher than those at younger age and are at least 10-fold greater than the drug cost of routine co-prescription of PPI[108].Besides,in patients aged ≥ 60 years treated with antiplatelet agents,a recent Dutch study showed that therapy with PPIs is cost-effective in reducing GIB[109].

PHARMACOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL INTERACTIONS BETWEEN PPIs AND ANTICOAGULANT AGENTS

As regards patients receiving oral anticoagulants,the preventive role of PPIs on GIB risk appears still controversial due to lack of evidence from RCTs.A large retrospective observational study[34] showed that,in patients treated with warfarin,PPI co-therapy significantly reduced the risk of upper GIB hospitalizations [HR: 0.55;number needed to treat (NNT): 78] among those concurrently using antiplatelet drugs,but not in the absence of a concurrent use of antiplatelet drugs[34].Another recent cohort study compared the data of 754389 person-years on anticoagulant treatment without PPIs with those of 264447 person-years in co-therapy with PPIs[31].In patients receiving warfarin,after adjustment for numerous covariates,including use of antiplatelet agents,the incidence of GIB hospitalizations was significantly reduced in those treated with PPIs compared to the group not treated with PPIs (74vs113 episodes per 10000 person-years)[35].PPIs may have a pharmacological interaction with warfarin due to their liver metabolism.Thus,in patients taking VKAs,we should monitor INR when initiating or discontinuing PPI therapy[33].

The pharmacokinetics of DOACs is different from that of warfarin.Among DOACs,dabigatran etexilate differs as it is administered as a prodrug and has a low bioavailability.Dabigatran capsules are intended for a release in the acidic environment of stomach,and the drug is absorbed in the distal small intestine.When PPIs are co-administrated with dabigatran,the latter has a lower solubility and its absorption decreases about 30%;its clinical efficacy,however,does not change[58,60,110,111].

Patients on triple therapy (DAPT plus OAT),e.g.,those with AF following PCI,are particularly at risk of GIB.The question is: Could the addiction of a PPI reduce the risk of bleeding in patients requiring triple therapy? The RE-DUAL PCI trial[112] randomized patients with AF post-PCI,treated with clopidogrel or ticagrelor,to dabigatran 110/150 mg twice daily dual therapy or to warfarin triple therapy.Dual therapy,regardless of PPI use,reduced the risk of major bleeding events or clinically relevant non-major bleeding eventsvswarfarin triple therapy;the composite efficacy endpoint was comparable.For GIB,no interaction was observed between study treatment and PPI use[112].Thus,PPIs in patients in triple therapy should be used regardless of anticoagulant chosen treatment.

The impact of gastroprotective agents is modest with rivaroxaban[90].The COMPASS study,a 3 × 2 partial factorial double-blind trial,randomized patients with stable cardiovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease to receive pantoprazole 40 mg daily or placebo,as well as rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily with aspirin 100 mg once daily,rivaroxaban 5 mg twice daily,or aspirin 100 mg alone for 3 years[113].No significant differences have been observed in clinical events (overt upper GIB,bleeding of presumed occult upper GI tract origin with documented decrease in Hb ≥ 2 g/dL,GI pain with underlying multiple gastroduodenal erosions,symptomatic gastroduodenal ulcer,and upper GI obstruction or perforation).In apost-hocanalysis with a broadened definition,pantoprazole therapy significantly reduced overt bleeding of gastroduodenal origin (HR: 0.45),gastroduodenal ulcer (HR: 0.46),and multiple gastroduodenal erosions (HR: 0.33),particularly in patients treated with ASA[114].PPIs used routinely in patients with stable cardiovascular disease receiving low-dose anticoagulation and/or aspirin may reduce bleeding from gastroduodenal lesions,but does not reduce upper gastrointestinal events[114].In a retrospective cohort study,when OAC treatment with PPI co-therapy was compared to that without PPI cotherapy,risk of upper GIB hospitalizations was lower for each anticoagulant: Apixaban (IRR=0.66);dabigatran (IRR=0.49);rivaroxaban (IRR=0.75);warfarin (IRR=0.65)[35].Therefore,PPI co-treatment might be able to reduce the risk of upper GIB in patients taking OACs regardless of the presence of risk factors.Obviously,more studies are needed in this field.The incidence of upper GIB hospitalization was most pronounced for dabigatran,potentially resulting from direct mucosal injury by the drug’s tartaric acid core[35].Using a nationwide claims database,in OAC-naïve patients with AF and a history of upper GIB before initiating OAC treatment,compared to the patients without PPI use,PPI co-therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of major GIB,by 40% and 36%,in the rivaroxaban and warfarin groups,respectively;in dabigatran,apixaban,and edoxaban users,PPI co-therapy did not show a significant reduction in the risk of major GIB[115].In a meta-analysis of ten studies,OAC and PPI co-therapy was associated with a lower odds of total and major GIB (OR: 0.67 and 0.68,respectively)[116].PPI co-therapy was related to a lower GIB odds by 24%-44% for all kinds of OACs,except for edoxaban;the protective effect of PPIs was more significant in concurrent antiplatelet drug users and in patients with a previous GIB history,HASBLED ≥ 3,or underlying gastrointestinal diseases (conditions at high bleeding risk)[116].

ROLE OF H. PYLORI INFECTION IN THE RISK OF UPPER GIB IN PATIENTS TREATED WITH ANTIPLATELET AND/OR ANTICOAGULANTS AGENTS

H.pyloriinfection is,together with the use of aspirin,one of the main risk factors in the pathogenesis of peptic ulcer disease (PUD)[117].This disease,however,does not develop in allH.pylori-positive patients or those taking aspirin;individual susceptibility to the infection and drug toxicity,therefore,are critical factors to the initiation of mucosal damage[2,117].A systematic review aimed to determine the influence ofH.pyloriinfection on the risk of upper GIB in patients taking ASA;it did not allow for strong conclusions due to the heterogeneity of the studies and the controversial results[118].H.pyloriinfection has an additive effect with NSAID use,whilst no interaction was shown with LDA use[117].H.pyloriinfection could have a synergistic or antagonistic interaction with LDA use in adverse gastroduodenal events depending on gastric acid secretion,which shows considerable geographic variation at the population level.While gastric acid secretion levels were not decreased and were well-preserved in most patients withH.pyloriinfection from Western countries,the majority of Japanese patients withH.pyloriinfection exhibited decreased gastric acid secretion[119].A meta-analysis showed that the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers during LDA therapy increased by approximately 70% in patients withH.pyloriinfection[120].The risk of upper GIB in patients taking LDA was greater inH.pyloripositive patients (OR: 2.32),as shown in another meta-analysis[121];however,the NNT to prevent one bleeding event/year was between 100 and more than 1000.Therefore,the possible cost-effectiveness of test and treatment strategies forH.pyloriin all patients receiving LDA is debatable,also considering the increasing primary resistance to antimicrobial agents[122].In addition,in patients taking LDA with an average risk of GIB,H.pylorieradication was never adequately evaluated as a first-line strategy to prevent PUD.Incidence rates of GIB were not significantly different between patients with previous PUB in whomH.pyloriwas eradicated and an average-risk cohort (i.e.,LDA-naïve patients without a history of ulcer and with unknown infection status)[123].Sostreset al[117] proposed to classify patients taking LDA into two groups (low and high bleeding risk),eradicatingH.pylorionly in the latter.Indications to eradicate always the infection are a previous peptic disease[2],older age,and the concomitant use of NSAIDs,oral anticoagulants,non-aspirin antiplatelet agents,and corticosteroids[117].

There are limited data in the literature as regards the relationship betweenH.pyloriand non-aspirin antiplatelet agents or oral anticoagulants.A recent cohort study demonstrated an increased (OR: 4.37) risk of haemorrhagic peptic disease inH.pylori-positive patients taking non-aspirin antiplatelet agents,while the risk was not increased in infected patients taking OACs[31].InH.pylori-eradicated patients,new users of DOACs had a significantly lower risk of upper GIB than new warfarin users[124].

Nearly all the available evidence is prone to bias with case-control or cohort studies;thus,more well-designed RCTs are needed,as well as pharmaco-economic evaluations assessing the risk-benefit ratio ofH.pylorieradication in LDA,non-aspirin antiplatelet agent,and oral anticoagulant users.In the recent Helicobacter Eradication Aspirin Trial,there was a significant reduction in incidence of the primary outcome in the active eradication group in the first 2.5 years of follow-up compared with the control group,but it was lost with longer follow-up (HR: 1.31) in the period after the first 2.5 year[125].

ARE THERE ALTERNATIVES TO PPIs?

H2RAs decrease gastric acid secretion by reversibly binding to histamine H2receptors located on gastric parietal cells,thereby inhibiting the binding and action of the endogenous ligand histamine[82].Their use is not significantly associated with ischemic stroke or MI[4,89];however,PPIs are superior to H2RAs in preventing GI bleeding in patients treated with antiplatelet agents,both as monotherapy and DAPT[126].Two RCTs demonstrated that PPIs are superior over misoprostol and ranitidine in the prevention of gastroduodenal ulcers and/or erosions induced by NSAIDs[127,128].The protective action of ranitidine on the gastroduodenal mucosa decreased significantly within 4 wk from the start of treatment;at 6 mo,it was significantly less effective than PPIs[127].Another study,besides,clearly showed that the effects of ranitidine in reducing gastric acid secretion is almost halved already on the third day of treatment[129].It is likely that this phenomenon depends on the onset of tachyphylaxis,typical of H2RA,but not of PPIs.When long-term antiplatelet treatment is needed,this aspect cannot be disregarded[33].Ranitidine,besides,significantly interferes with the antiplatelet activity of the LDA,probably reducing its intestinal absorption,although it does not seem to attenuate the antiplatelet power of clopidogrelin vitro[130,131].The incidence of GIB events in the PPI group was significantly lower than that in controls in patients treated with ticagrelor,whereas in the H2RA group no significant difference was observed[103].In a study,LDA users with a history of peptic ulcers who did not have gastroduodenal mucosal breaks at initial endoscopy were randomly assigned to receive famotidine (20 mg bid) or omeprazole (20 mg qd) for 6 mo.The incidence of gastroduodenal mucosal breaks was 33.8% among the patients receiving famotidine,and 19.8% among those receiving omeprazole.The two patient groups had comparable incidence rates of gastroduodenal ulcers and bleeding.Multivariate analysis showed that use of the PPI was an independent protective factor (OR: 0.47)[132].In the PROTECT trial,after 600-mg clopidogrel loading for elective PCI,clopidogrel-sensitive patients were recruited and randomly assigned to add rabeprazole 20 mg daily or famotidine 40 mg daily.Baseline platelet measures performed with light transmittance aggregometry and VASP-P assay did not differ significantly between the groups.At the 30-d follow-up,the incidence of high platelet resistance was similar between the famotidine and rabeprazole groups[133].

Misoprostol,compared to PPIs,is also significantly less effective in prolonged gastroprotective treatment,and is more frequently burdened by adverse events (diarrhoea and abdominal pain)[109].Besides,there are possible negative implications for patient compliance and costs,as it requires the administration of at least 1-2 tablets twice daily,compared to the single administration of PPIs.

Vonoprazan is the first molecule of a new class of drugs,the potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs),capable of effectively reducing gastric acid secretion.These drugs could be useful in preventing gastroduodenal mucosal lesions induced by antiplatelet agents.In a RCT,in patients with a history of PUD requiring long-term LDA therapy for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular protection,peptic ulcer recurrence rates were significantly lower with vonoprazan 10 mg than with lansoprazole 15 mg[134].In vitro,no effect of vonoprazan on the platelet-aggregating inhibitory activity of aspirin was shown,andin vivothere is no significant interaction between the two drugs[135].Data on the potential interaction of vonoprazan with other antiplatelet agents and oral anticoagulants,however,are not yet available.

Potential NSAID gastroprotectors,including allantoin and rebamipide,are being evaluated.The latter was found to be as effective as misoprostol[136] but not in patients treated with naproxen[137],and better tolerated.However,there is still no evidence about their efficacy in preventing gastrointestinal damage from antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants.

Concomitant therapy with both PPIs and H2RAs was associated with a 50% reduction of risk of GIB in patients treated with anticoagulants,with the maximum effect when both drugs were used in association[138].Being mediated by the bleeding reduction from pre-existing gastroduodenal ulcers,this protective effect seems confined to the upper GI tract,and to patients with previous peptic disease or GIB[59].

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE GUIDELINES AND REGULATORY INDICATIONS

Several guidelines or position papers by various American[139-142],Asiatic[143],European[144-147],and Italian[33,148,149] Societies of Cardiology,Gastroenterology,Pharmacology,and General Practitioners (Table 3) deal with gastroprotection in patients taking antiplatelet and/or oral anticoagulant treatment.

GASTROPROTECTION IN THE REAL WORLD: UNDERPRESCRIPTION AND OVERPRESCRIPTION

Prophylactic PPI use in patients at risk of GIB is still largely ignored by physicians,despite many studies and recommendations.In a Danish study on 46000 patients treated with DAPT after an acute MI,an under-utilisation of gastroprotection with PPIs was shown,notwithstanding an annual risk of GIB of about 1% in the general population,and of 1.7% in patients at high risk[54].This phenomenon was also documented in Italy[150].In Spain,a retrospective study on patients hospitalized for ACS showed that,at discharge,most patients received gastroprotective agents,mainly PPIs[151];however,in only one every three cases of patients treated with clopidogrel,the recommendation of the Food and Drugs Administration and of the European Medicine Agency was not followed as omeprazole or esomeprazole was prescribed[151].A study retrospectively evaluated patients with upper GIB diagnosis who had taken NSAIDs,antiaggregants,or anticoagulants;of them,86% had moderate to high risk for GIB,but 81% of these patients were not actually using PPIs.In patients with a previous history of peptic ulcer bleeding,PPI prophylaxis was not provided in one every four cases[152].A Danish nationwide register-based study identified citizens at an increased ulcer bleeding risk and showed only 44.4% concomitantly treated with PPIs[153].From a database,elderly patients (>64 years old) who were chronic (>3 mo) users of LDA and had an indication for PUD prophylaxis as per the ACG-ACCF-AHA guideline document were identified.Overall,only 40% of patients received a PPI[154].In another retrospective drug utilization study,in China,the prescribing pattern of LDA revealed a poor awareness of preventing GI injury with combined protective medications[155].Under-prescription is frequent also in very high-risk patients.A retrospective study included patients on combined antithrombotic therapy receiving PPIs,reporting an overall rate of PPI co-therapy of 40.9%,with only 22.3% of patients receiving PPIs for GIB prophylaxis[156].

There are,however,some positive findings.In the All Nippon AF In the Elderly (ANAFIE) Registry[157],a prospective,observational study among elderly (aged >75 years) Japanese non-valvular AF patients in the real-world clinical setting,PPIs were used in 36.9% of patients.Compared with the PPIs-group,the PPIs+group included a greater proportion of female patients and had significantly higher CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores,as well as higher prevalence of several comorbidities.In the PPIs+group,54.6% of patients did not have GI disorders and were likely prescribed a PPI to prevent GIB events.Compared with patients not receiving anticoagulants,a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving anticoagulants received PPIs.For patients receiving anticoagulants,antiplatelet drugs,and both drugs,rates of PPI use were 34.1%,44.1%,and 53.5%,respectively (P<0.01).These data suggest that PPIs were actively prescribed in high-risk cases.In a Dutch monocentric observational registry on ACS patients,besides,from 2010 to 2014 PPI prescription at discharge significantly increased from 34.7% to 88.7%[100].

On the other hand,overprescription has also been observed.In a Dutch primary care database[158] with all new PPI prescriptions,valid PPI indications at initiation were seen only in 44% of PPI users.Predictors of inappropriately initiated PPI use were older age and use of non-selective NSAIDs,COX-2 inhibitors,and LDA.An inappropriate indication was found in more than half of PPI users in primary care (one of the leading causes was unnecessary ulcer prophylaxis related to drug use)[158].An observational study on a large insurance claims database showed that the incidence of potentially inappropriate PPI prescriptions significantly increased from 4.8% in 2013 to 6.4% in 2017 (age,male gender,multimorbidity,and use of drugs with bleeding risk being independent determinants)[159].The main predictor of inappropriate PPI use is the number of received medications[160].We particularly need efforts,thus,to deprescribe PPIs after interruption of antithrombotic therapies.

CONCLUSION

In patients at thrombotic risk,antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs are effective for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.Antithrombotic drugs,unfortunately,can cause GIB,sometimes with a fatal outcome[23,45,53,161].Besides,GIB,in turn,may often require treatment discontinuation,and this may have harmful consequences in the medium and long term on ischemic events[162].Therefore,gastroprotection is required in patients at increased bleeding risk[163].PPIs are often prescribed,regardless of the bleeding risk,in patients with many CVDs such as ACS,mechanical or surgical revascularizations,ischemic strokes,and TIAs.The prescription of these drugs should be based on the presence of stents and the need for DAPT,as well as on the GIB risk profile of the patients (age >65 years,previous upper GIB events,concomitant therapy with anticoagulants or NSAIDs,andH.pyloriinfection).

In patients treated with single antiplatelet therapy for the first time,standard dose of PPIs should be used only in the presence of GIB risk factors[2,23,33,54,126].There is currently no evidence to recommend one PPI agent as gastroprotection for the risk of upper GIB in the absence of any risk factors[1,28,31,51,57].Choosing a PPI lacking interference with the hepatic CYP450 enzymes might be preferred in patients treated with clopidogrel[33,84,91,92].Among patients with a history of aspirin-induced upper GIB,the use of a standard dose of PPI in association with LDA should be preferred to substitution with clopidogrel to reduce the risk of upper GIB recurrence[43,44,139].Currently,available data do not allow answering the question about the differences between individual PPIs in their impact on the risk of adverse cardiovascular events due to the small number of such studies,design heterogeneity,and differences in the inclusion criteria and endpoints,as well as in the rate of administration of individual PPIs.

As for antiplatelet therapy,the most effective gastroprotection in patients treated with oral anticoagulants,when necessary,is that with standard PPI dosage[58-60].For VKAs,INR monitoring is required when starting or stopping PPI therapy[33].For DOACs,PPI use is recommended in the presence of risk factors[36,37].We recommend to use standard dose of PPIs in patients treated with DAPT,or with double or triple antithrombotic treatment[139,145].Specific recommendations are dedicated to patients with cirrhosis[60,64,165].Obviously,PPIs are not effective against bleeding from the small intestine or from the colon[33].

The interaction between antiplatelet therapy andH.pyloriinfection remains also controversial[31,113,120,121],requiring randomized prospective studies.Finally,there is no evidence that other gastroprotective drugs are more effective than PPIs[109,130,134,135,137].

In conclusion,in patients treated with antiplatelet therapy with an increased risk of GIB,use of PPIs should be considered mandatory[33,141,144].In other cases,the decision to use PPIs in patients treated with thienopyridines or anticoagulant agents should be based on risk-benefit ratio,assessing both cardiological and gastroenterological risks in order to balance them.Validated therapies to prevent bleeding risk from VKAs and DOACs are not available[139,142].Recent studies seem to demonstrate a benefit of the PPI treatment also in patients taking anticoagulants[34,35,90,113,138].We need further prospective,randomized studies to accurately evaluating the protective role of PPIs during OAC

therapy,considering the stratification of both thrombotic and haemorrhagic risk and potential long-term consequences.Meanwhile,physicians should both be aware of potential issues related to long-term use of PPIs and weigh benefits of PPI therapy along with the likelihood of the potential risks.Discussing evidence behind the reported side effect profile will help clarify the growing concerns over PPI therapy[166].Table 4 synthesize some suggestions on this topic.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Abrignani MG was responsible for the conception and design of the manuscript,and he wrote the first original draft;Lombardo A,Braschi A,Renda N,Abrignani V,and Lombardo RM contributed to the design of the manuscript and made critical revisions for important intellectual content;all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license,which permits others to distribute,remix,adapt,build upon this work non-commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms,provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Italy

ORCID number:Maurizio Giuseppe Abrignani 0000-0002-0237-7157;Alberto Lombardo 0000-0002-4527-2507;Annabella Braschi 0000-0003-1972-7595;Nicolò Renda 0000-0002-8785-0627;Vincenzo Abrignani 0000-0002-7035-8900.

S-Editor:Chen YL

L-Editor:Wang TQ

P-Editor:Chen YL