CRlSPR/Cas9-based functional characterization of PxABCB1 reveals its roles in the resistance of Plutella xylostella (L.) to Cry1Ac,abamectin and emamectin benzoate

OUYANG Chun-zheng ,YE Fan ,WU Qing-jun ,WANG Shao-li ,Neil CRlCKMORE ,ZHOU Xu-guo,GUO Zhao-jiang#,ZHANG You-jun#

1 State Key Laboratory of Vegetable Biobreeding,Deapartment of Plant Protection,Institute of Vegetables and Flowers,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Beijing 100081,P.R.China

2 Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture,Guangzhou 510642,P.R.China

3 School of Life Sciences,University of Sussex,Brighton BN1 9QG,UK

4 Department of Entomology,University of Kentucky,Lexington,KY 40546-0091,USA

Abstract The identification of functional midgut receptors for pesticidal proteins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is critical for deciphering the molecular mechanism of Bt resistance in insects. Reduced expression of the PxABCB1 gene was previously found to be associated with Cry1Ac resistance in the diamondback moth,Plutella xylostella (L.). To directly validate the potential receptor role of PxABCB1 and its contribution to Bt Cry1Ac toxicity in P.xylostella,we used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate a homozygous knockout ABCB1KO strain with a 5-bp deletion in exon 3 of its gene. The ABCB1KO strain exhibited a 63-fold resistance to Cry1Ac toxin compared to the parental DBM1Ac-S strain. Intriguingly,the ABCB1KO strain also exhibited significant increases in susceptibility to abamectin and emamectin benzoate. No changes in susceptibility to various other Bt Cry proteins or synthetic insecticides were observed. The knockout strain exhibited no significant fitness costs. Overall,our study indicates that PxABCB1 can protect the insect against avermectin insecticides on one hand,while on the other hand it facilitates the toxic effect of the Bt Cry1Ac toxin. The results of this study will help to inform integrated pest management approaches against this destructive pest.

Keywords: Bacillus thuringiensis,Plutella xylostella,CRISPR/Cas9,ABCB1,bioinsecticide resistance

1.Introduction

The insect pathogenBacillusthuringiensis(Bt) produces diverse insecticidal proteins (e.g.,Cry and Vip toxins)during sporulation,and Bt biopesticides and transgenic Bt crops based on these insecticidal proteins play a significant role in the current insecticide and transgenic plant markets (Pinoset al.2021). Bt biopesticides are extremely effective,target-specific,and ecologically safe,making them one of the best solutions for pest management in public health,agriculture and forestry(Bravoet al.2011). Moreover,109 million hectares of transgenic Bt crops have been planted worldwide in 2019(ISAAA 2019). Despite the advantages it has brought to agriculture,the long-term use of Bt-based products is threatened by the development of pest resistance in the field (Tabashnik and Carrière 2017;Xiao and Wu 2019). Therefore,it is necessary to fully comprehend the molecular mechanisms of insect resistance to these proteins in order to effectively utilize Bt technology.

Bt infection models in insects have been widely investigated,and the basic mechanism of action has been well understood: Bt protoxins must be proteolytically activated in the insect gut before binding to midgut receptors and subsequently forming pores in the cell membrane,leading to midgut perforation and insect death (Jurat-Fuenteset al.2021). Well characterized midgut receptors include alkaline phosphatase (ALP),aminopeptidase N (APN),cadherin (CAD) and ATPbinding cassette (ABC) transporters (Pinoset al.2021).Binding of the toxin to its cognate receptor is the key to both its specificity and its virulence,and insects can develop high levels of resistance through modifications of these receptors (Adanget al.2014;Jurat-Fuentes and Crickmore 2017;Petersonet al.2017). A thorough understanding of the relationship between the toxin and its functional midgut receptor is crucial for delaying insect resistance to Bt toxins. The transmembrane proteins known as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are found in a wide variety of animals and are crucial for biological transport. They typically consist of two highly conserved domains: cytosolic nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) and transmembrane domains (TMDs)(Deanet al.2022). Energy for transport is produced by the NBDs hydrolyzing ATP,while the TMDs are involved in binding and exchanging a wide variety of substrates(Reeset al.2009). The ABC transporters have been linked to multidrug resistance in humans,bacteria and nematodes (Silvaet al.2015). In insects,ABC transporters,particularly those in the ABCB,ABCC and ABCG subgroups,have been implicated in insecticide detoxification and Bt toxicity (Gottet al.2017;Wuet al.2019). ABCB1 belongs to the Mdr/Tap subfamily of the ABC transporter superfamily,also known as P-glycoprotein or MDR1,and functions as an efflux pump for xenobiotic substances with broad substrate specificity (Silvaet al.2015). Due to these characteristics,ABCB1 is a major player in drug and insecticide resistance (Merzendorfer 2014;Gottet al.2017;Satoet al.2019).

The diamondback moth,Plutellaxylostella(L.),is one of the most notorious pests ofBrassicacrops,and significantly threatens the global agricultural industry(Furlonget al.2013). Because of its remarkably efficient adaptation to insecticides in the field,it has been utilized as a model insect for studying the underlying resistance mechanisms to chemical and biological insecticides (Guoet al.2015a;Liet al.2016). ABCB1 has previously been identified as a possible midgut receptor of the Bt Cry1Ac toxin and the reduced expression ofABCB1is associated with Bt resistance inP.xylostella(Guoet al.2020b;Zhouet al.2020).

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)system has been utilized as a potent gene editing tool for studying gene functions in non-model insects (Sun Det al.2017). We have previously knocked out several midgut genesinvivousing the CRISPR/Cas9 system in order to successfully determine their functional receptor role in Bt Cry1Ac toxicity inP.xylostella(Guoet al.2019,2020b;Sunet al.2022). In this study,we disrupted thePxABCB1from a susceptible strain ofP.xylostellato create a homozygous mutant strain,ABCB1KO.Our findings indicated that the knockout ofPxABCB1reduces the sensitivity of the insect to Bt Cry1Ac toxin but increases the sensitivity to abamectin and emamectin benzoate without significantly compromising physiological fitness. This study provides genetic evidence for ABCB1 acting as a functional midgut receptor of Bt Cry1Ac toxin while contributing to the detoxication of other insecticides.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.lnsect strains

The Bt-susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S and the Bt-resistant strain NIL-R were described in our previous studies (Guoet al.2015b,c;Zhouet al.2020;Kanget al.2022b). The DBM1Ac-S strain has never been exposed to Bt toxins or insecticides,while the NIL-R has developed >5 000-fold resistance to Bt Cry1Ac toxin compared to the susceptible DBM1Ac-S strain. The larvae were raised on Jingfeng No.1 cabbage (Brassicaoleraceavar.capitata) and the adults were reared with a 10% honey/water solution in a strictly controlled environment of 25°C,65% humidity and a 16 h L:8 h D photoperiod.

2.2.CRlSPR/Cas9 component preparation

The full-length cDNA sequence of thePxABCB1gene(GenBank accession no.MK613451) was cloned in our previous study (Zhouet al.2020),and its genomic DNA(gDNA) sequence was retrieved from theP.xylostellagenome deposited in the Lepbase database (http://ensembl.lepbase.org/Plutella_xylostella_pacbiov1/). The CRISPR/Cas9 system contains two components: singleguide RNA (sgRNA) and the Cas9 protein. For selecting suitable sgRNAs targeting thePxABCB1gene,we used the CRISPR RGEN tool Cas-Designer (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer/) to design several suitable sgRNAs targeting exon 3 or exon 5 (encoding a genespecific transmembrane domain) of thePxABCB1gene(Appendix A). The absence of predicted off-target effects of these sgRNAs was determined using the CRISPR RGEN tool Cas-OFFinder (http://www.rgenome.net/casoffinder/) and BLASTn searches against theP.xylostellagenome database (DBM-DB,http://59.79.254.1/DBM/)and the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). We conducted fusion-PCR using the highfidelity PrimeSTAR Max DNA polymerase (TaKaRa,Dalian,China) to provide a template DNA for sgRNA synthesis. Two primers were used,one to encode the T7 polymerase binding site (italics) and sgRNA target sequence (N20,underlined) for thePxABCB1gene(CRISPR-B1-F1: 5´-GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATA GGCGCATTCCTCCTGCAAGCCAGTTTTAGAGCTAG AAATAGC-3´;CRISPR-B1-F2: 5´-GAAATTAATACGACTC ACTATAGGCATCGGGATGCCAGACAATGGTTT TAGAGCTAGAAATAGC-3´;CRISPR-B1-F3: 5´-GAAATTA ATACGACTCACTATAGGAGACAAATGTTATATC ACCGGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC-3´;CRISP R-B1-F4:5´-GAAATTAATACGACTCACT ATAGGTCATGGCAC TCATTAAGGGTGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGC-3´),and the other to act as a reverse primer and encode the remaining sgRNA sequences (CRISPR-R:5´-AAAAGCACCGACTCGGTGCCACTTTTTCAA GTTGATAACGGACTAGCCTTATTTTAACTTGCTATTTC TAGCTCTAAAAC-3´). The PCR products were purified using the DNA Clean-up Kit (NEB,Ipswich,MA,USA),and analyzed for purity and concentration with a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham,MA,USA). The sgRNA was synthesized by the GeneArt Precision gRNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham,MA,USA)invitro.The sgRNA samples obtained were used immediately or stored in aliquots at–80°C until use. All experimental procedures and methods were performed in accordance with the kit instructions. The recombinant Cas9 protein fromStreptococcuspyogeneswas obtained commercially(Thermo Fisher Scientific,Waltham,MA,USA).

2.3.Egg collection and microinjection

The procedures of egg collection and microinjection were described previously (Guoet al.2019). To obtain fresh single eggs,we induced fertility in mated female adults by thinly coating a dry microscope slide (24 mm×50 mm)with fresh cabbage leaf juice. Collected eggs were microinjected with a mixture of Cas9 (300 ng µL–1) and sgRNA (150 ng µL–1) within 2 h of oviposition. The microinjection was performed using a FemtoJet 4i and an InjectMan 4 microinjection system (Eppendorf,Hamburg,Germany),with glass needles (Sutter Instrument,Novato,CA,USA) pulled by a P-97 micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument,Novato,CA,USA) and then polished with an EG-401 microgrinder (Narishige,Tokyo,Japan). The injected egg masses were kept in the strict environmentally controlled temperature and humidity as described above.

2.4.Exuviate-based PCR and mutant detection

To obtain their individual genotypes without harming the normal growth and development ofP.xylostella,we used a method of extracting gDNA from the tiny pupal exuviates shed by fourth-instar larvae. Trace amounts of gDNA were isolated from individual exuviate using the KAPA Express Extract DNA Extraction Kit(KAPA Biosystems,Boston,MA,USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Direct sequencing of PCR products amplified with primers ABCB1-exon3-F:5´-TCACCGCGGCACTACTTTC-3´ and ABCB1-exon3-R: 5´-TACGACAGCACTATCGC-3´;ABCB1-exon5-F: 5´-TTTTTATTTTTATCCCCAGTGACGT-3´,ABCB1-exon5-R: 5´-TCATTCTTACCAGCCCTGCG-3´)was conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai,China) to identifyABCB1mutations at the target sites of exon 3 or exon 5. The PCR reactions (in a total volume of 25 µL)contained 12.5 µL of PrimeSTAR Max Premix (2×),0.5 µL of ABCB1-exon3/5-F (10 µmol L–1),0.5 µL of ABCB1-exon3/5-R (10 µmol L–1),150 ng of gDNA template and 10.5 µL of ddH2O. The PCR program was as follows: one cycle of 98°C for 2 min;35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s,55°C for 15 s and 72°C for 30 s;and a final cycle of 72°C for 10 min. The presence of double peaks on the sequencing chromatogram around the Cas9 cleavage site indicated a mutation at that site and these PCR products were ligated to the pEASY-T1 cloning vector for precise insertion/deletion (indel) mutation detection.

2.5.Homozygous mutant strain construction

To establish a stable homozygous knockout strain of thePxABCB1gene,we adopted a germline mutation and mutation screening strategy based on the life cycle ofP.xylostellaas described previously (Guoet al.2019;Sunet al.2022). Briefly,G0generation larvae were developed by microinjecting a mixture of gene-specific sgRNA and Cas9 protein into the preblastodermP.xylostellaeggs.Mutant moths validated by direct sequencing were then inbred to develop the G1generation,and specific indel mutants were identified by both direct and cloned DNA sequencing. Only in the sgRNA1-injected group were sufficient heterozygous individuals containing the same indel alleles identified,and the moths were sib-crossed to develop the G2generation (Appendix A). The G2progeny harboring homozygous mutant alleles were identified by direct sequencing,and the mutant homozygotes were finally mass-crossed to construct the stable homozygous mutant ABCB1KO strain in G3.

2.6.Cry1Ac toxin preparation and bioassays

Both the protoxin and trypsin-activated forms of Cry1Ac,Cry2Aa and Cry2Ab were prepared as described previously (Gonget al.2020;Guoet al.2020a;Kanget al.2022a). These Bt toxin preparations were stored in 50 mmol L–1Na2CO3(pH 9.6) at–20°C until use.

The toxicity of the various insecticides toP.xylostellawas tested in leaf-dip bioassays following our previously described procedures (Guoet al.2021;Qinet al.2021a,b;Xuet al.2022). Briefly,fresh cabbage leaves were cut into appropriate sizes,soaked in dilutions of Bt toxin solution,taken out and placed on paper towels to air dry before use. At each concentration,30 healthy early thirdinstar larvae were selected,with 10 larvae per Petri dish serving as three replicates. The results were recorded after 72 h,and larvae were considered dead if they had died or showed severe growth retardation.

Bioassay data were analyzed using the POLO Plus 2.0 Software (LeOra Software,Berkeley,CA,USA) to calculate LC50and 95% CL values. The LC50values of two strains whose 95% CL values did not overlap were considered to be significantly different,and the resistance ratio was calculated by dividing the LC50value of each strain by the LC50value of the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S.

2.7.Genetic analysis of Cry1Ac resistance

The ABCB1KO strain was crossed with the susceptible DBM1Ac-S strain to investigate the inheritance associated with thePxABCB1knockout resistance trait. Fifty unmated female or male adults were selected from the ABCB1KO strain to mate with 50 male or female adults from the DBM1Ac-S strain,and the resulting F1progeny were then tested with 10 mg L–1of Cry1Ac protoxin,a concentration which can kill all recessive heterozygous F1individuals. Based on the single-concentration method described elsewhere (Guoet al.2019),the Cry1Ac resistance dominance (h) was calculated as:h=(Survival of F1hybrid offspring–DBM1Ac-S)/(Survival of resistance strains–DBM1Ac-S),with values ranging from 0 (completely recessive) to 1 (completely dominant).

2.8.Fitness cost analysis

The effects of the knockout on the subsequent developmental stages of surviving larvae were analyzed by comparing several biological parameters,including pupation percentage,pupal weight,pupation duration,eclosion percentage,adult longevity and egg hatchability,with the variousP.xylostellastrains. From each strain,100 healthy and active second-instar larvae were chosen and split into five groups. Fresh cabbage leaves with no toxin were used to raise the larvae. Real-time monitoring data were recorded for the various biological parameters.

2.9.Statistical analysis

The biological data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 Software (IBM Corp.,USA). Data are shown as the mean±SEM. Determinations of statistical significance were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s tests.

3.Results

3.1.CRlSPR/Cas9 mediates efficient PxABCB1 knockout

To establish the homozygousPxABCB1knockout strain,we designed a germline mutation and mutation screening strategy based on the life cycle ofP.xylostella(Fig.1). For the selected sgRNA1-injected group,243 fresh eggs from the Bt Cry1Ac-susceptibleP.xylostellastrain were microinjected with a mixture of Cas9 proteins and the sgRNAs targeting exon 3 ofPxABCB1(Fig.2-A).Around 25% (62/243) of injected eggs completed incubation,pupation and eclosion (Table 1). These 62 adults were considered to be generation 0 (G0). The pupal exuviates shed by fourth-instar G0larvae were collected for exuviate-based PCR to detect the specific mutation events introduced by CRISPR (Fig.2-B).Nucleotide sequencing showed that 48 G0insects carried mutations at the target site. We pooled the mutant individuals and mass crossed them to create a new generation (G1).

Fig.1 Schematic diagram of the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout system in Plutella xylostella. A,the different kinds of midgut receptors for the Bt Cry1Ac toxin in P. xylostella. The specific ABC receptor which was knocked out in this study has been indicated.B,the life history of P.xylostella. The gDNA was extracted from pupal exuviates shed by fourth-instar larvae to determine the genotype. C,detailed protocol for establishing the PxABCB1 knockout strain. The gray dashed boxes show the genotypic selection of each generation. The individuals with mutated alleles were selected from the injected G0 generation of P. xylostella to generate the G1 generation. The single allele mutants were identified in the G1 generation and used to generate the G2 generation. The homozygous individuals in the G2 generation were selected to obtain the final PxABCB1 knockout strain ABCB1KO. For these genotypes,gray columns represent autosomes,and different colors represent different mutation events.

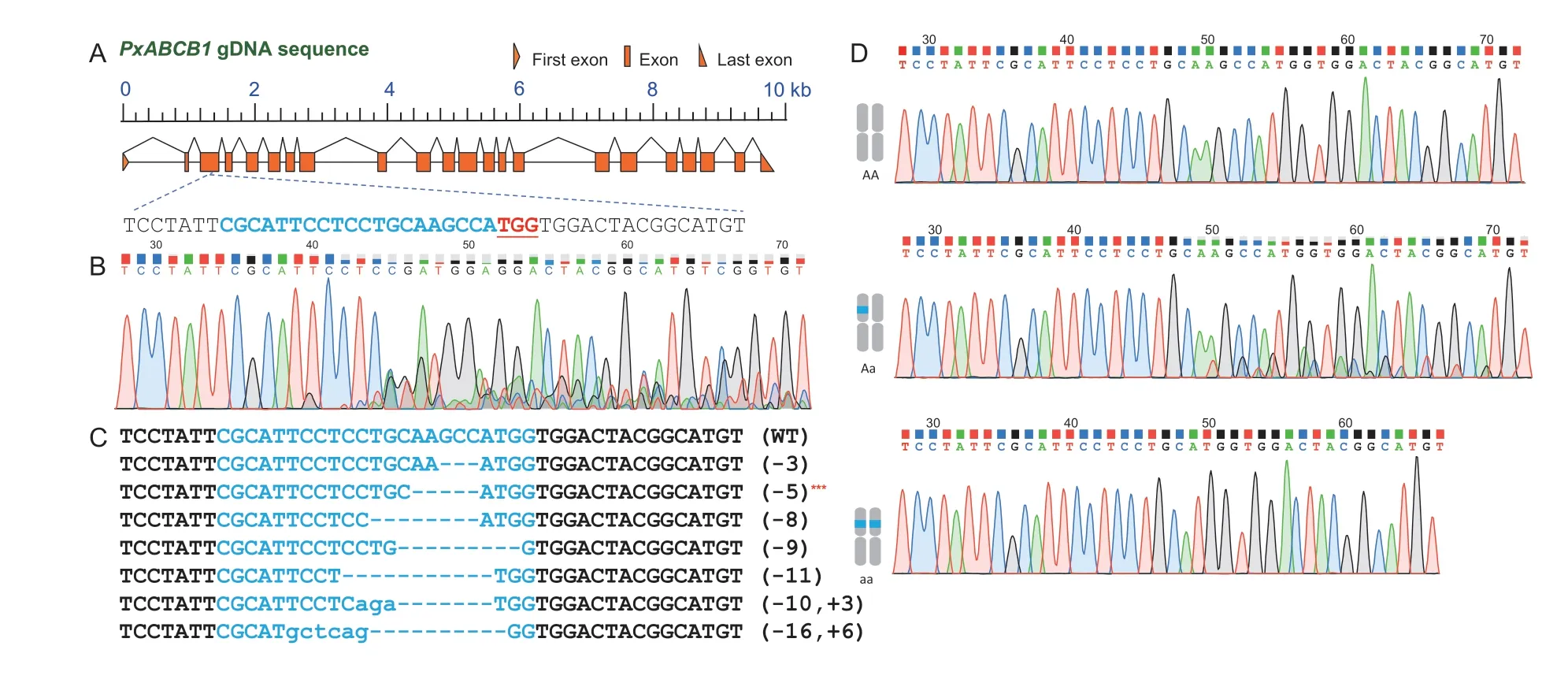

Fig.2 Mutagenesis of PxABCB1 mediated by CRISPR/Cas9. A,structure of the PxABCB1 gene and the target site of sgRNA.The genomic structures are drawn to scale. Exons are shown with orange boxes and introns with connecting lines,and the first and last exons are represented by triangles. The sgRNA target site is located in exon 3,and its binding sequence is colored blue while the PAM sequence is highlighted in red. B,a direct sequencing chromatogram of DNA derived from a mixed sample from the mutated G0 generation. C,sequences of indels flanking the target site in G1 larvae. Deleted nucleotides are represented by dashes,and inserted nucleotides are marked with lowercase letters. The altered nucleotide length is shown on the right (+,insertion;–,deletion),and WT represents wild type. Asterisks denote the selected monoallelic mutants with enough individuals to allow sib-crossing to generate G2 strains. D,representative chromatograms of direct sequencing of the PCR products derived from WT (upper graph),heterozygote (middle graph) and mutant homozygote (lower graph) G2 individuals.

Mutation scanning of 78 individuals from the G1generation revealed 34 wild-type homozygotes,9 biallelic mutants and 35 monoallelic mutants. Details of the eight types of identified monoallelic indel mutations are shown in Fig.2-C. Among these mutation types,the deletion of a 5-bp segment was highly represented(Table 1). The deletion of this 5 bp in exon 3 ofPxABCB1causes a premature stop codon and produces a truncated and presumably non-functional protein.The 15 larvae with this 5-bp deletion were selected for interbreeding to generate homozygous individuals.By direct sequencing of 120 individuals from the next generation (G2),28 homozygous mutant individuals were identified,so the ratio of the homozygote was approximately 23% (28/120) and the ratio of the genders was approximately 1:1 (15 males and 13 females).The 28 homozygous mutants were crossed to create a stable homozygous mutant strain ABCB1KO in the next generation (G3) (Fig.1-B).

3.2.Resistance of the knockout strain to Bt Cry1Ac toxin

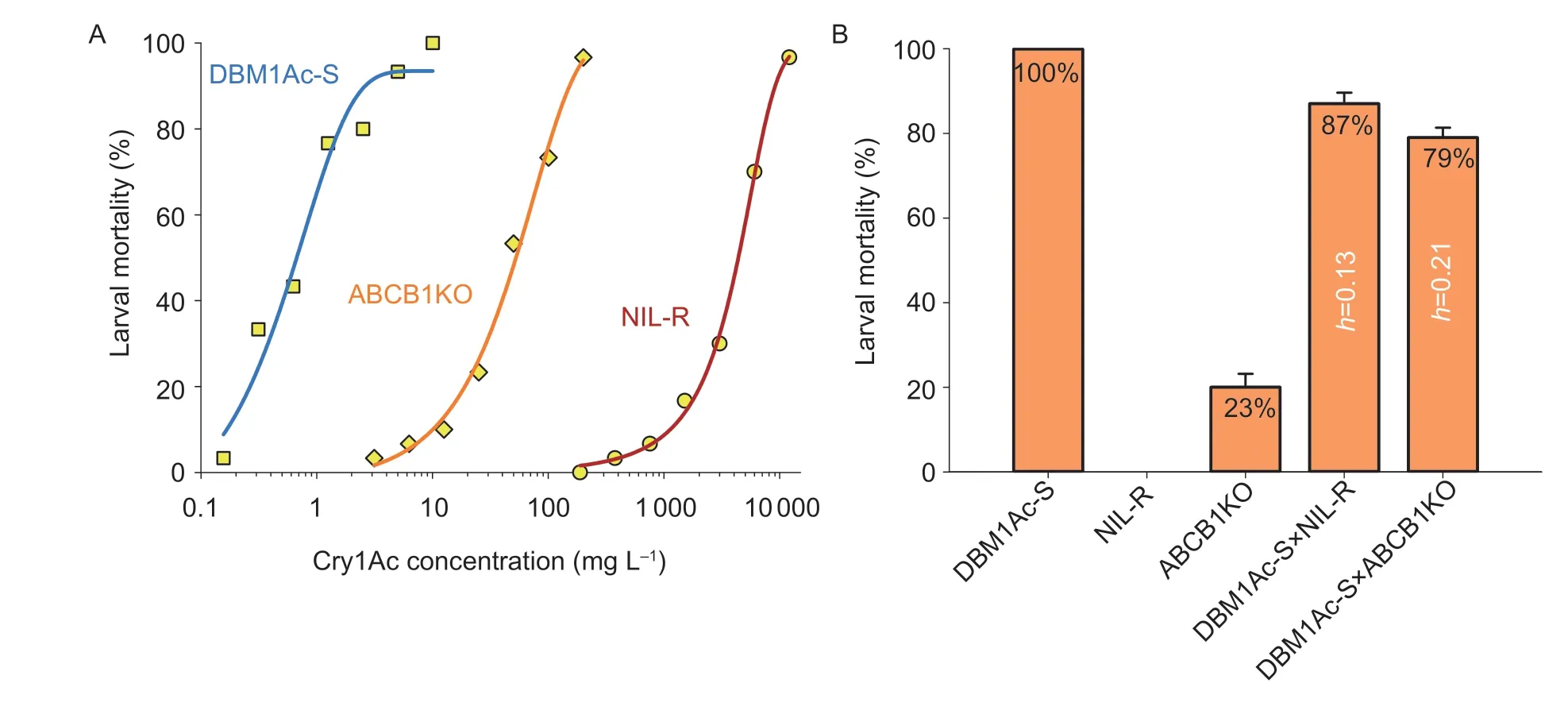

Previously,we had determined that reduced expression of various Cry1Ac receptors,including PxABCB1,is associated with Cry1Ac resistance inP.xylostella(Zhouet al.2020). To directly verify the involvement of PxABCB1 in the resistance phenotype,we assessed the level of resistance in the knockout strain. Our results showed that the knockout strain had significantly reduced susceptibility to Cry1Ac,though nothing like the Cry1Acresistant strain NIL-R (Fig.3-A). The LC50value for Cry1Ac in the knockout strain [44.56 (34.82–58.25) mg L–1] was 63-fold higher than that of the susceptible DBM1Ac-S strain [0.71 (0.48–0.99) mg L–1],but over 80-fold lower than that of the NIL-R strain [3 684.73(2 590.20–5 612.34) mg L–1]. These results nonetheless providedinvivofunctional evidence for PxABCB1 as a midgut Cry1Ac receptor inP.xylostella.

Table 1 CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout of PxABCB1 in Plutella xylostella

Fig.3 Resistance analysis of the PxABCB1 knockout strain ABCB1KO. A,log dose-response curves for Plutella xylostella larvae from the susceptible strain DBM1Ac-S,the knockout strain ABCB1KO,and the near-isogenic resistant strain NIL-R exposed to Cry1Ac protoxin. Two nonlinear dosage-mortality regression curves without intersections represent the two LC50 values with nonoverlapping 95% CL values,which can be considered as significantly different. B,interstrain complementation tests for allelism with diagnostic doses of Cry1Ac protoxin. The F1 progeny are produced by crossing one susceptible strain and the resistant strains in all pairwise combinations,and the mean value of larval mortality rate and the dominance parameter h of each crossed group are shown on each column. Error bars in each column indicate standard errors of the mean from 10 biological repeats.

To investigate the inheritance of Cry1Ac resistance in the ABCB1KO strain,we mass crossed the ABCB1KO and DBM1Ac-S strains in pairs and observed the reactions of their third-instar larvae and the F1progeny to 10 mg L–1Cry1Ac protoxin (Fig.3-B). This dose renders larvae from DBM1Ac-S completely non-viable,whereas larvae from NIL-R are unaffected. The progeny from the cross between ABCB1KO and the DBM1Ac-S strain showed a 21% survival rate. This gave a dominance parameter (h) of 0.21 and suggested an incompletely recessive inheritance pattern (Fig.3-B).

3.3.Effects of knockout on susceptibility to other insecticides

Recent studies have reported that some Bt toxin receptor alterations can result in changes in the susceptibility to other insecticides (Xiaoet al.2016). To test whether this was true for the Cry1Ac resistance phenotype associated the disruption ofP.xylostellaPxABCB1,12 commercially available insecticides againstP.xylostellawere tested for cross-resistance.

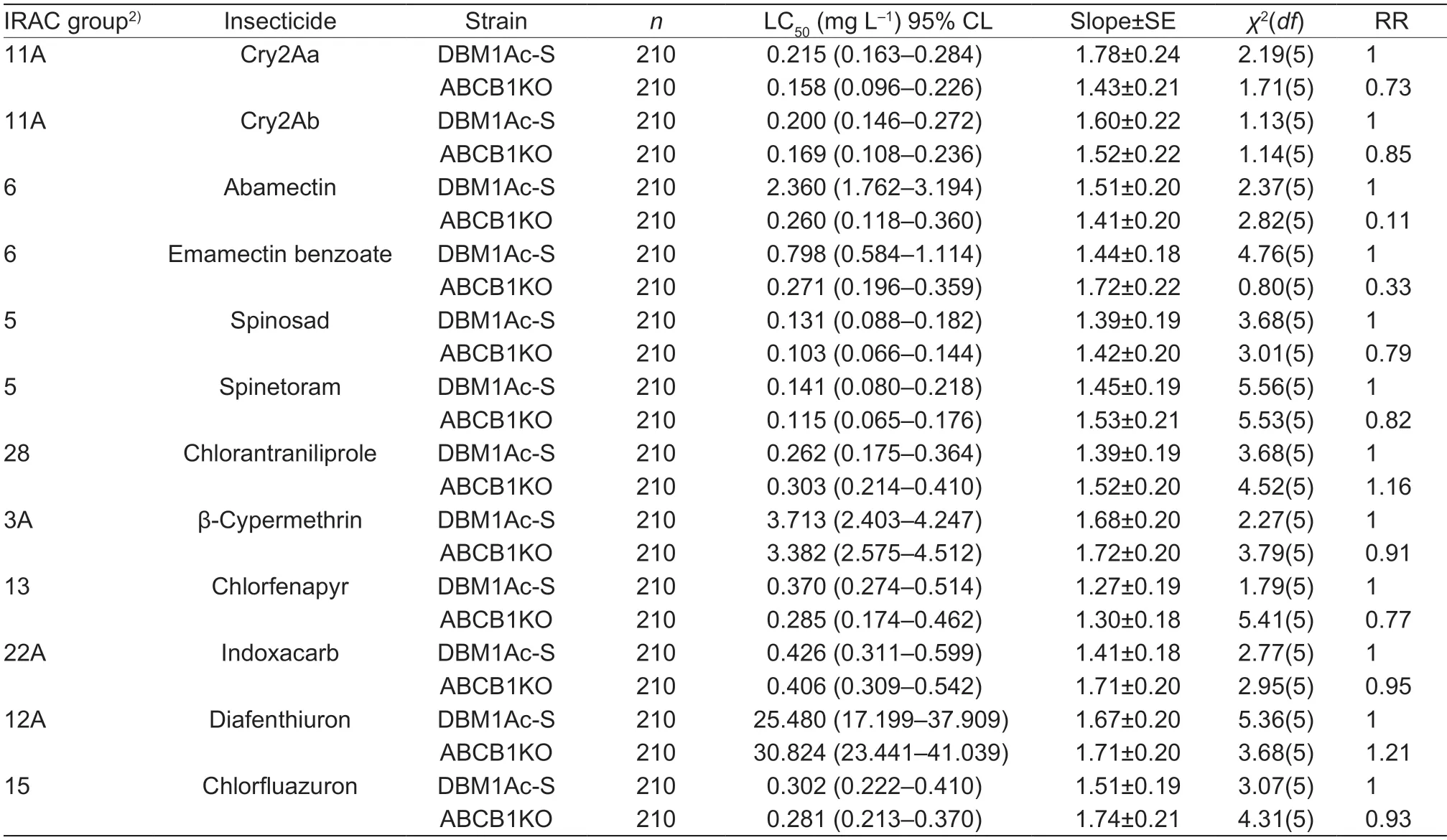

Third-instar larvae of the ABCB1KO strain were tested against two other Bt Cry toxins (Cry2Aa and Cry2Ab)and 10 other insecticides (abamectin,emamectin benzoate,spinosad,spinetoram,chlorfenapyr,β-cypermethrin,indoxacarb,diafenthiuron,chlorfluazuron and chlorantraniliprole) and the bioassay results are shown in Table 2. These results indicated that,relative to the parental DBM1Ac-S strain,ABCB1KO larvae showed significant increases in susceptibility (3–10 fold)to abamectin and emamectin benzoate. For the other 10 insecticides,there was no significant alteration in susceptibility.

3.4.No fitness costs associated with the knockout

Previous studies have shown that a fitness/resistance balance is maintained by regulating non-receptor paralog expression inP.xylostella(Guo Zet al.2022),but it was not observed in a strain in which four receptors were knocked out by CRISPR/Cas9 (Sunet al.2022). We evaluated any fitness costs in thePxABCB1knockout strain by comparing several biological parameters,including pupation percentage,pupal weight,pupation duration,eclosion percentage,adult longevity and egg hatchability,with the DBM1Ac-S and NIL-R strains. No significant differences among the three strains were observed in any of the six biological parameters (Fig.4),implying that any significant biological function of ABCB1 can be replaced by other homologous genes inP.xylostella.

Fig.4 Analysis of fitness costs in the ABCB1KO strain. A,hatchability. B,pupation rate. C,eclosion rate. D,pupal weight. E,pupation duration. F,adult longevity. Data are presented as mean±SEM,n=5 biologically independent samples with 20 larvae per replicate. ns,not significant. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test was employed for the comparison.

4.Discussion

CRISPR-based gene editing makes it possible to accurately and efficiently evaluate gene activityinvivoin diverse insects (Sun Det al.2017). We employed this technology to demonstrate the relationship between theABCB1gene and resistance to a variety of insecticides inP.xylostella(Fig.1). The ABCB1KO strain developed a 63-fold resistance to Bt Cry1Ac,which is consistent with its role as abonafidemidgut functional receptor for Cry1Ac toxin. The Cry3Aa toxin has previously been shown to bind ABCB1 and induce the lysis of insect cells inChrysomelatremula,DiabroticavirgiferaandLeptinotarsadecemlineata,while silencingABCB1reduced the susceptibility to Cry3Aa toxin (Pauchetet al.2016;Niuet al.2020;Güneyet al.2021). With evidence that ABCB1 can act as a receptor for both Cry1Ac and Cry3Aa,we tested whether there was any cross resistance Cry2Aa and Cry2Ab inP.xylostella,but found none. Furthermore,ABCB1 knockdown was found to have no effect on susceptibility to the Cry1Fa or Cry1Ca toxins inSpodopteraexigua(Zuoet al.2018),nor did a knockout effect on susceptibility to the Cry1Ab,Cry1Fa or Vip3Aa toxins inSpodoptera frugiperda(Liet al.2022). The association of a toxin with its receptor is a prerequisite for its full function (Jurat-Fuentes and Crickmore 2017). This binding is specific to particular domains/motifs within both toxin and receptor (Tanakaet al.2016;Adegawaet al.2017;Tanakaet al.2017),with structural changes hindering toxin binding (Liuet al.2018). Binding itself may not be sufficient for activity since the toxin may have to bind in a certain orientation relative to the cell membrane to facilitate pore formation(Endo 2022). The specificity inherent in the toxin-receptor interaction means that while proteins such as Cry1Ac and Cry3Aa can bind productively to ABCB1 others,such as Cry2Aa and Cry2Ab,cannot. Furthermore,the situation can differ among insects,in that a particular protein may act as a receptor for a given toxin in one insect but not in another. For example,cadherin acts as a receptor for Bt Cry1Ac inHelicoverpaarmigera,but not inP.xylostella(Guoet al.2015b).

Table 2 Susceptibility of third-instar Plutella xylostella larvae from the DBM1Ac-S and ABCB1KO strains to 12 different insecticides1)

ABCB1disruption only induces a relatively low level of resistance to Cry1Ac inP.xylostella. This is consistent with our previous finding of significant redundancy in Cry1Ac receptor function in this insect,with several different proteins (including ABCB1,ABCG1,ABCC2,ABCC3,ALP,APN1 and APN3a) able to act as functional receptors,and high levels of resistance are only observed when multiple receptors are down-regulated or knocked out (Sunet al.2022).

Recently,the transcription factor PxJun was discovered,which can be controlled byPxMAP4K4whose gene is encoded within the Cry1Ac resistance locus(BtR-1) on chromosome 15. PxJun can negatively regulate the expression ofPxABCB1,resulting in Cry1Ac resistance inP.xylostella(Qinet al.2021a). We found that the gene forPxABCB1itself is located on chromosome 8 and encodes one of several receptors whose coordinated down-regulation through a signaling pathway headed byPxMAP4K4is responsible for highlevel resistance to Cry1Ac (Guoet al.2020b,2021,2023). In a previous study,we discussed how fitness costs associated with the coordinated down-regulation of the receptor genes (PxmALP,PxAPN1,PxAPN3a,PxABCB1,PxABCC2,PxABCC3andPxABCG1)could be mitigated by the simultaneous up-regulation of non-receptor paralogs (Guoet al.2020b) and that a transcription factor fushi tarazu factor 1 (FTZ-F1) under the control of the MAPK cascade was crucial in this process (Guo Zet al.2022). However,PxABCB1andPxmALP(also on chromosome 8) are not under the control of FTZ-F1 (Qinet al.2021a;Guo Let al.2022)and it is unclear whether any of the non-receptor paralogs under the control of FTZ-F1 can compensate for the loss of PxABCB1. Although no fitness costs were observed with the ABCB1KO strain,this does not mean that the upregulation of a compensatory protein is required,as we have previously shown that individual receptor proteins can be knocked out without fitness costs,and these costs are only seen when multiple receptors are disabled (Guo Zet al.2022;Sunet al.2022).

Recent research has revealed that ABC receptor alterations affecting susceptibility to Bt Cry toxins increase sensitivity to other insecticides (Xiaoet al.2016). Here,we detected increases in susceptibility to abamectin and emamectin benzoate in the ABCB1KO strain. According to an earlier study,abamectin exposure dramatically upregulates the expression ofPxABCB1inP.xylostella,and the expression ofPxABCB1in abamectinresistant strains was higher than in susceptible strains(Tianet al.2013). Our experimental results provide direct evidence thatPxABCB1is associated with the susceptibility to both abamectin and emamectin benzoate inP.xylostella. Likewise,a knockout ofSeABCB1significantly increases susceptibility to abamectin and emamectin benzoate by around 3-fold inS.exigua(Zuoet al.2018).Spodopterafrugiperdaalso became susceptible to emamectin benzoate afterSfABCB1was knocked out (Liet al.2022). The mortality ofH.armigeraexposed to abamectin significantly increased after silencing of theHaABCB1gene (Xianget al.2017),and avermectin-resistantTetranychuscinnabarinusshowed a considerable rise inTcABCB1transcription levels(Xuet al.2016). Avermectin exposure also inducedDmABCB1overexpression inDrosophilalarvae (Chenet al.2016). Notably,a common finding among these studies is that the overexpression ofABCB1is related to the resistance to abamectin and emamectin benzoate in different insects. Hence,it is conceivable to hypothesize that ABCB1 acts as a functional pump to remove these poisonous compounds from cells in order to minimize the damage to the arthropods.

The susceptibilities to spinosad,spinetoram,chlorfenapyr,β-cypermethrin,indoxacarb,diafenthiuron,chlorfluazuron and chlorantraniliprole remained unchanged in the ABCB1KO strain. InS.exigua,knockout ofABCB1also did not affect the toxicity of these eight insecticides (Zuoet al.2018). Disruption ofABCB1rendersS.frugiperdamore susceptible to emamectin benzoate,β-cypermethrin,and chlorantraniliprole,but has no influence on the toxicities of indoxacarb,tebufenozide,bifenthrin,chlorpyrifos,abamectin,chlorfenapyr,or decamethrin (Liet al.2022). These three lepidopteran pests differed somewhat in howABCB1responded to the insecticides,indicating thatABCB1exhibits speciesspecific insecticide susceptibility. Despite this variation,overexpression ofABCB1is associated with excessive insecticide resistance in insects and other arthropods,includingAedescaspius(Porrettaet al.2008),Heliothis virescens(Auradeet al.2010),Rhipicephalusmicroplus(Pohlet al.2011),Lepeophtheirussalmonis(Igboeliet al.2012),Aedesaegypti(Figueira-Mansuret al.2013),Anophelesstephensi(Episet al.2014),Blattella germanica(Houet al.2016) andLaodelphaxstriatellus(Sun Het al.2017). According to these studies,we can infer thatABCB1is a potential node of negative crossresistance between Bt Cry toxins and other insecticides.

5.Conclusion

In this study,we successfully constructed aPxABCB1gene knockout line using CRISPR/Cas9 and verified its importance in the resistance ofP.xylostellato several insecticides,namely Bt Cry1Ac toxin,abamectin and emamectin benzoate. Although it is reasonable to speculate that the respective resistance mechanisms involve loss of receptors and efflux pump functionality,other approaches,such as transcriptomic comparison between the ABCB1KO and DBM1Ac-S strain using RNAseq,could be employed to probe this further. Knowledge about the molecular mechanisms by which lepidopteran species have evolved resistance to Bt is still growing,and deciphering the vast and intricate networks involved is a daunting task. Considering the functional redundancy between different,independent midgut receptors inP.xylostella,performing single or multiple knockouts of receptors to verify their contribution to Bt resistance and cross-resistance to other insecticides is a valid approach for solving this problem.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Laboratory of Lingnan Modern Agriculture Project,China (NT2021003),the National Natural Science Foundation of China(32022074,32221004 and 32172458),the Beijing Key Laboratory for Pest Control and Sustainable Cultivation of Vegetables,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,and the Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-CSCB-202303).

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendixassociated with this paper is available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.05.023

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- The association between the risk of diabetes and white rice consumption in China: Existing knowledge and new research directions from the crop perspective

- Linking atmospheric emission and deposition to accumulation of soil cadmium in the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain,China

- Genome-wide association study for numbers of vertebrae in Dezhou donkey population reveals new candidate genes

- Are vulnerable farmers more easily influenced? Heterogeneous effects of lnternet use on the adoption of integrated pest management

- lnfluences of large-scale farming on carbon emissions from cropping:Evidence from China

- Spatio-temporal variations in trends of vegetation and drought changes in relation to climate variability from 1982 to 2019 based on remote sensing data from East Asia