Are vulnerable farmers more easily influenced? Heterogeneous effects of lnternet use on the adoption of integrated pest management

LI Kai ,JIN Yu ,ZHOU Jie-hong

1 School of Economics,Qufu Normal University,Rizhao 276826,P.R.China

2 China Academy for Rural Development,Zhejiang University,Hangzhou 310058,P.R.China

3 School of Public Affairs,Zhejiang University,Hangzhou 310058,P.R.China

Abstract The Internet is believed to bring more technological dividends to vulnerable farmers during the green agriculture transformation. However,this is different from the theory of skill-biased technological change,which emphasizes that individuals with higher levels of human capital and more technological endowments benefit more. This study investigates the effects of Internet use on farmers’ adoption of integrated pest management (IPM),theoretically and empirically,based on a dataset containing 1 015 farmers in China’s Shandong Province. By exploring the perspective of rational inattention,the reasons for the heterogeneity of the effects across farmers with different endowments,i.e.,education and land size,are analyzed. The potential endogeneity issues are addressed using the endogenous switching probit model.The results reveal that: (1) although Internet use significantly positively affects farmers’ adoption of IPM,vulnerable farmers do not benefit more from it. Considerable selection bias leads to an overestimation of technological dividends for vulnerable farmers;(2) different sources of technology information lead to the difference in the degree of farmers’rational inattention toward Internet information,which plays a crucial role in the heterogeneous effect of Internet use;and(3) excessive dependence on strong-tie social network information sources entraps vulnerable farmers in information cocoons,hindering their ability to reap the benefits of Internet use fully. Therefore,it is essential to promote services geared towards elderly-oriented Internet agricultural technology information and encourage farmers with strong Internet utilization skills to share technology information with other farmers actively.

Keywords: Internet use,IPM,vulnerable farmers,technological dividends,endogenous switching probit model

1.Introduction

Promoting the green transformation of agricultural production is both an initiative to address global climate change and a requirement for high-quality agricultural development (IPCC 2019). Green transformation of agricultural production aims to enhance total factor productivity through an agricultural technology revolution,making the innovation and development of green production technologies and systems crucial (MARA 2018). This transformation not only demands higher resource endowments from farmers but also presents a new challenge to the agricultural technology extension system. Therefore,leveraging the advantages of the Internet to promote green transformation in agricultural production has emerged as a focal point in global policy and research (Akeret al.2016;Walteret al.2017;Shiet al.2019;Shenet al.2022).

A growing number of studies demonstrate that the Internet has profoundly changed the way farmers produce and live. The Internet can bring technological dividends to farmers by improving information acquisition capabilities,optimizing household resource allocation,and enhancing human capital and social capital,thereby improving agricultural production efficiency (Zhuet al.2020;Zhenget al.2021;Nguyenet al.2023),promote agricultural technological progress (Ma and Wang 2020;Khanet al.2021;Yuanet al.2021;Li F Det al.2022;Zhenget al.2022;Liet al.2023) and e-commerce adoption (Maet al.2020b),increase farmers’ income (Maet al.2020a;Zhouet al.2020;Khanet al.2022;Zheng and Ma 2023),increase consumption (Houet al.2019;Zhuet al.2021;Vatsaet al.2022),and improve the nutrition security (Twumasiet al.2021),happiness and well-being of residents (such as Maet al.2020a;Ankrahet al.2021;Nieet al.2021;Yuan 2021;Zhenget al.2023).

However,although existing studies have shown that different groups have obtained heterogeneous technological dividends from Internet use,they have not reached a consensus on which group benefits more from Internet use. In terms of Internet use on farmers’income,some studies believe that Internet use has a greater impact on low-income farmers and helps narrow the income gap between farmers (Zhang and Li 2022).However,other studies have reached the opposite conclusion. Bonfadelli (2002),Maet al.(2020a),and Zhuet al.(2022) argue that Internet use has a greater impact on high-income households and has widened the income gap among rural households. Some studies also pointed out that the impact of Internet use on farmers’ income is non-linear. The effects of Internet use on agricultural productivity exhibit heterogeneity as well. Zhenget al.(2021) and Nguyenet al.(2023)found that Internet use can narrow the differences in the technical efficiency among farmers,and farmers with lower technical efficiency benefit more from Internet use.On the other hand,Sunet al.(2022) investigated the effects of Internet use on agricultural labor productivity based on the data from 1 122 rural households in four provinces in China,which found that Internet use increased the labor productivity gap within rural. This applies to the effects of Internet use on the adoption of green production technologies. Maet al.(2022) found that the impact of Internet use on farmers’ organic fertilizer varies,and farmers with higher education levels are more influenced. In contrast,more studies found that the influence of Internet use on vulnerable farmers is more pronounced. The use of the Internet significantly increases the adoption rate of water-saving irrigation technologies and straw conversion technologies,especially among small farmers with low education levels (Zhenget al.2022). Internet-based agricultural technology extension services promote small-scale and older farmers’ adoption of green production technologies such as soil formula fertilization and water-saving technologies more pronounced (Gaoet al.2020;Li B Zet al.2022).

Existing studies have also not provided a consistent explanation of the heterogeneity. Considering that the Internet is a typical skill-biased technological change,existing studies mainly explain the differences in technological dividends brought to farmers by Internet use from the perspectives of cognition and learning abilities and technological attributes. Gaoet al.(2020),Zhenget al.(2022),and Nguyenet al.(2023) explained that the Internet can compensate for the disadvantages of vulnerable farmers in access to information.However,these contradict the findings that highly educated and young farmers obtain more technological benefits. Moreover,this explanation is mainly based on the assumption that non-vulnerable farmers have already achieved a higher technology adoption rate or technological efficiency. This comparison may be biased and contrary to the theory of skill-biased technological change. Differences in agricultural technology attributes may be another important reason for the heterogeneity of Internet use. Ma and Zheng (2022) found differences in the impact of smartphone use on pesticide and fertilizer spending. Caiet al.(2022) found that mobile Internet use has a greater impact on facilitating the spread of capital-intensive technologies than laborintensive technologies.

Although the above conclusions do not provide a perfect explanation for the heterogeneity of Internet use,they do inspire us to further explore the ways and extent to which the Internet is utilized and trust and attention are allocated towards Internet information rather than Internet usage itself. Therefore,this paper focuses on the Internet’s role as an information dissemination channel. It examines the reasons for the heterogeneity of the impact of Internet use on different groups from the perspective of rational inattention. This helps better eliminate the digital utilization divide and advances the role of the Internet in promoting farmers’ technology adoption. This study’s contributions are mainly twofold.First,using the endogenous switching model,we not only effectively solve the endogenous problem of farmers’ Internet use but also decompose the effect of Internet use on farmers’ adoption of integrated pest management (IPM). We answer the question of whether this effect is more pronounced for the group of vulnerable farmers and whether it delivers more technological dividends to them. Second,by analyzing the sources of farmers’ information,we explore the relationship between rational inattention and Internet technological dividends,enriching existing studies on the heterogeneity of Internet use in promoting the green transformation of agricultural production.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.Section 2 provides a theoretical analysis. Using the concept of rational inattention,we theoretically deduce the possible impact of Internet use on vulnerable farmers’technology adoption decisions. Section 3 introduces the data sources,variable settings,and research methods. In this section,we analyze the advantages of the endogenous switching probit model compared with other endogenous processing methods such as PSM and RBP,and we demonstrate the calculation of ATT/ATU/ATE and their differences. Section 4 presents the empirical results. The treatment effect of Internet use on farmers’ IPM adoption and the heterogeneity of Internet use is analyzed. Finally,Section 5 draws conclusions and contributions of this paper,puts forward policy implications to improve the effect of Internet use,and points out some limitations of our current study.

2.Theoretical analysis

Rational inattention refers to the selective disregard of information not worth processing rather than gathering all decision-relevant information or applying all available information to the decision-making process (Sims 2003).Rational inattention is a manifestation of bounded rationality,which occurs because decision-makers have limited attention and information-processing abilities in uncertain decision environments (Simon 1997).

Agricultural technology diffusion is a process through which new technologies spread across complex social networks (Barnett and Mobarak 2021;Beamanet al.2021). Farmers often rely on multiple sources of information when deciding on technology adoption.Compared to traditional agricultural production technologies,IPM is more systematic,resulting in a higher degree of information intensity. Adopters often face more pronounced information asymmetry and uncertainty. Therefore,it puts forward higher requirements for farmers’ attention distribution and information-processing ability,which are more likely to induce farmers’ rational inattention.

Although Internet use helps improve farmers’ access to information,it also demands higher attention allocation abilities. This means that farmers need a greater ability to process information from different sources. On the one hand,Internet use facilitates technology adoption by enhancing farmers’ access to information on IPM technology and their information processing abilities(Ogutuet al.2014;Kaila and Tarp 2019). On the other hand,the huge amount of information and the mix of accurate and false information on the Internet will inevitably lead to information redundancy and a lower density of valuable information. This situation increases the cost of farmers’ information processing,thus inducing rational inattention by farmers (Kahneman 1973;Caplin and Dean 2015;Handel and Schwartzstein 2018).Therefore,whether Internet use can encourage farmers to adopt IPM depends not only on their information processing ability but also on their trust and attention allocation towards Internet information.

Vulnerable farmers are more likely to adopt a rational inattention attitude towards Internet information because they face a more prominent contradiction between their information needs and information processing abilities.From the perspective of the diffusion of innovation theory,vulnerable farmers often lag behind due to the constraints in household resource endowment and risk attitude in the diffusion of green production technologies.These farmers are often considered part of the “late majority” or “laggards” (Rogers 2003). They have a higher threshold for technology adoption,and their adoption behavior often occurs after most surrounding farmers have already adopted the technology. As a result,vulnerable farmers have a higher demand for the quantity,quality,and sources of technology information(Xiong and Xiao 2021). Moreover,the limited coverage of public agricultural technology extension services and commercial agricultural technology services tend to focus on large-scale farmers (Zhou 2017),which restricts vulnerable farmers’ access to agricultural technology information in the external environment.This is also the main reason for the weak informationprocessing ability of vulnerable farmers. Therefore,vulnerable farmers usually decide whether to adopt the technology by observing specific groups (e.g.,friends,neighbors,or similar farmers) while adopting a rational inattention attitude towards information from other sources (Banerjeeet al.2018;Benyishay and Mobarak 2019;Guptaet al.2020).

3.Data and methods

3.1.Data sources

The data used in this study were obtained from a survey of wheat farmers in Shandong Province from 2019 to 2021,which focused on the adoption of fertilizer reduction and efficiency technologies. A stratified sampling method was employed to select the samples. The surveyed farmers were located in 17 national-level grain-producing counties in eight cities,e.g.,Qingdao,Dezhou,Heze,and Weifang,and 2–3 townships were chosen from each target survey county.Next,1–2 villages were selected from each township,and around 15–20 farmers were sampled from each village. Members of our research group completed questionnaires based on face-to-face interviews with farmers. A total of 1 156 questionnaires were collected,of which 1 015 were valid,with an effective rate of 87.8%. For the specific sample location distribution,please refer to Appendix A.

Shandong was chosen as the survey site for two reasons. First,it is a major wheat-growing province,and its planting area ranks second after Henan Province.At the same time,Shandong Province faces enormous pressure on the transformation of green production.In 2020,the total amount of chemical fertilizer use in Shandong ranked second in the country,with an average chemical fertilizer use of with an average chemical fertilizer use of 719.55 kg ha–1(NBSC 2021). Second,Shandong Province has one of the highest levels of digital agricultural development in China. The province has successively issued the “Shandong Province Digital Village Development Strategy Implementation Opinions”and “Shandong Province Digital Village Development Plan(2022–2025)”,focusing on improving digital infrastructure construction and developing digital agriculture. By the end of 2020,all villages in Shandong Province had achieved fiber optic and 4G network coverage,and more than 70 000 agricultural information societies were established. These conditions make Shandong Province an ideal sample for analyzing the effect and heterogeneity of Internet use on the green transformation of agricultural production.

In this study,IPM for wheat is used as an indicator of green production for two reasons. First,IPM technology encompasses a wide range of management technologies,including physical,biological,and agricultural,all of which are information-intensive. This necessitates farmers to access more technological information,making it easier to reflect on the advantages of using the Internet. Second,the adoption rate of IPM technology for wheat is relatively low1At present,the control of wheat pests and diseases in China is still dominated by chemical control. By the end of 2019,there were 22 biopesticides (active ingredients) approved for use in wheat cultivation in China,with 56 products accounting for only 2.92% of all registered products.,and farmers have limited access to technology information. Therefore,this study helps highlight the differences in farmers’ preferences for information from different sources.

3.2.Variables

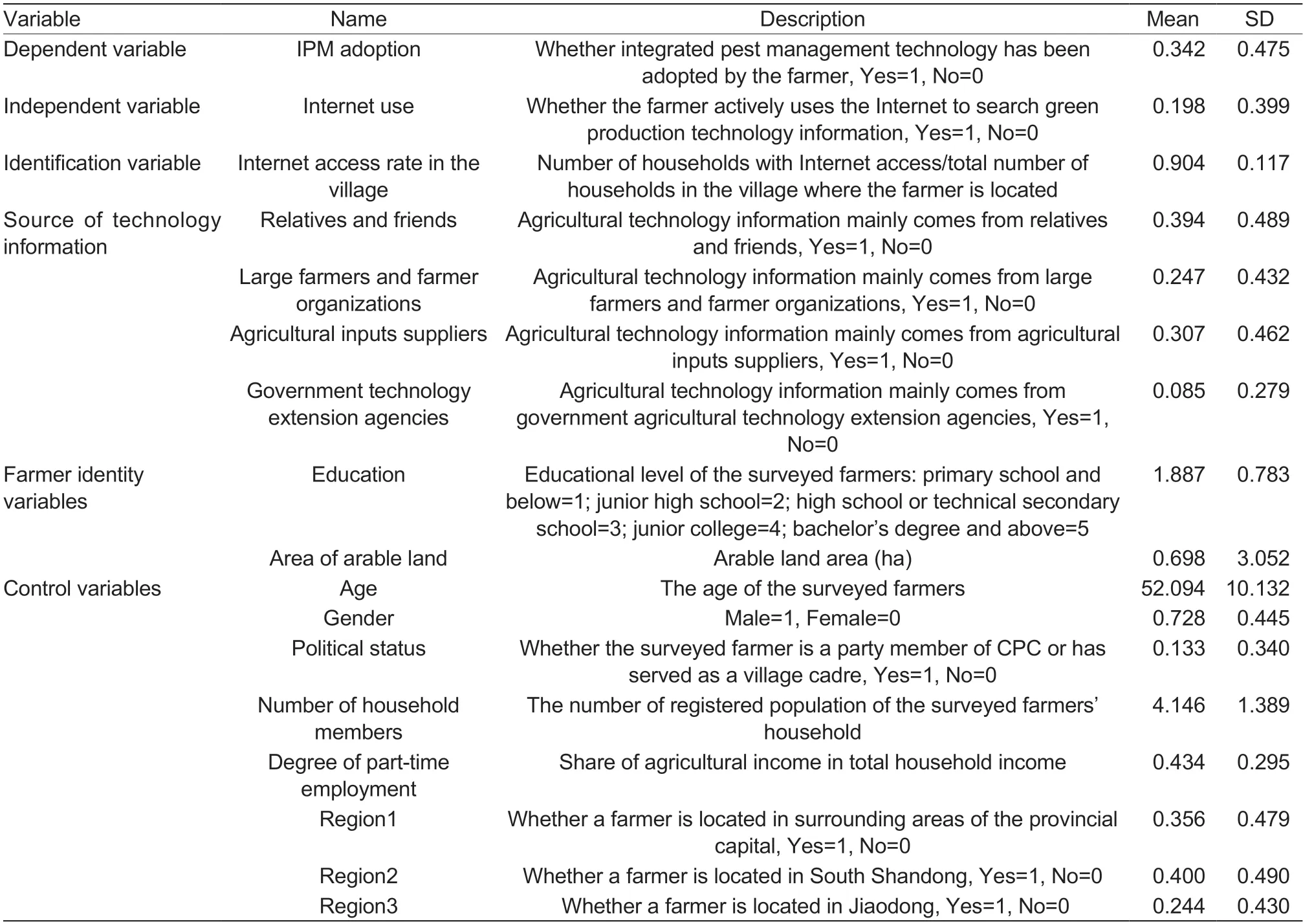

The variable settings are as follows.

(1) Dependent variable: IPM adoption (i.e.,whether IPM technology has been adopted by farmers).

(2) Independent variable: Internet use. In recent years,the Internet access rate in rural areas of China has increased significantly,and the gap between farmers’Internet access abilities has continued to narrow.Differences in utilization ability have become a key factor influencing Internet technological dividends (Akeret al.2016;Bowen and Morris 2019). Therefore,we focused on the effect of farmers’ Internet use on the adoption of IPM and measured the Internet utilization ability of farmers by whether they actively use the Internet to search for IPM information. Only when farmers can actively use the Internet to search for technology information can the Internet become a “new agricultural tool”.

(3) Identification variable: Internet access rate at village level. Whether a farmer uses the Internet or not is the result of his or her intentional choice. The self-selection problem needs to be addressed using an endogenous switching regression model. Choosing appropriate identification variables is the first step in building this model. With reference to existing studies (Maet al.2018;Denget al.2019),the average village Internet access rate(the ratio of the number of households connected to the Internet to the total number of households) was chosen as the identification variable. The Internet has an obvious network externality. The higher the average Internet access rate in the village,the more obvious the network externality of the Internet in interpersonal communication and information dissemination and the higher the probability of farmers accessing and using the Internet.However,the village’s average Internet access rate does not directly affect farmers’ decision-making regarding technology adoption. These data were derived from a name list of village WeChat group members provided by the village director. A farmer was considered to have internet access if at least one person from the household was in the WeChat group.

(4) Source of technology information. From studies related to Chinese farmers’ adoption of technology,farmers obtain the technology information from multiple sources,including relatives and friends,large farmers and farmer organizations,agricultural inputs suppliers,and governmental technology extension agencies. There are differences among the four information sources in terms of content,dissemination method,and credibility of technical information. Differences in farmers’ reliance on different information sources lead to differences in the degree of rational inattention to Internet information by farmers (Zhang and Li 2014;Oliveret al.2020;Panet al.2021).

(5) Farmer identity variables. Education and area of arable land. In order to verify whether Internet use brings more technological dividends to vulnerable farmers in the transformation of green production,we originally intended to determine whether farmers are “vulnerable farmers”by age,education,and area of arable land. With the rise of rural land transfer,Chinese farmers are experiencing a differentiation based on productivity and management forms (Zhou 2017). Various new agricultural operators received more policy support,and their stronger resource capture ability has created a “crowding-out effect” on small farmers (Zhaoet al.2018). This makes small farmers more vulnerable,and it is the reason why we chose the arable land area to judge vulnerable farmers.In addition,according to Zhang and Luo (2022),the reason why it is difficult for small farmers to expand their production scale is mainly due to the limitation of family resource endowment and individual land management ability. Therefore,we considered small farmers with lower educational levels and older ages as vulnerable farmers.However,there was a high correlation between the age and education of the sample farmers,and the average age of the farmers was over 52 years old. Therefore,this study finally chose education and the area of arable land as variables to identify farmers’ identities.

(6) Control variables. Based on existing studies,we used variables such as gender,number of household members,degree of part-time employment,political status,and location as control variables (Kabir and Rainis 2015;Ma and Abdulai 2019;Gaoet al.2020;Xie and Huang 2021).

3.3.Descriptive statistics

From the results of the descriptive statistical analysis(Table 1),the average adoption rate of IPM for the sample farmers is only 34.2%. According to the diffusion of innovation theory,it has not yet crossed the critical point of self-diffusion,and effective agricultural technology promotion is still needed. In terms of the ability to use the Internet,only 19.8% of farmers actively used the Internet to search for IPM information. In sharp contrast,the average village Internet access rate has reached 90.4%. This also validates that the difference in Internet technological dividends stems more from utilization ability rather than access ability. In terms of technology information sources,most farmers (39.4%) mainly accessed agricultural technology information through relatives and friends. The proportion of farmers who mainly accessed information from agricultural material dealers and large farmers and farmer organizations accounted for 30.7 and 24.7%,respectively. The number of farmers whose main information source is government agricultural technology extension agencies is the lowest,accounting for only 8.5%2It should be noted that since a small number of farmers will obtain information from two information channels at the same time,and some farmers have chosen “other channels”,hence the sum of the percentages of the four main information channels is not equal to 100%.. This result indicates that farmers’ trust on different technology information sources presents a clear “pattern of difference sequence” (Fei 2013). Moreover,the survey reveals that although farmers trust agricultural technology information from the government,few farmers use it as their primary information source. This is because the government’s public agricultural technology extension services are far from meeting the needs of farmers (Sun 2021).

The average age of the sample farmers was 52,indicating notable aging characteristics. The educational level of the farmers was low,and the average education level was not up to junior high school. The average arable land area of the sample farmers is 0.698 ha,and there are only 19 large-scale farmers (farmers with arable land areas of 3.333 ha or more),accounting for 1.87%. This proportion is slightly lower than that of large-scale farmers(2.62%),as shown in the announcement of the Third Agricultural Census of Shandong Province,China. The average household population of the surveyed farmers was 4. Agricultural income accounts for only 43.4% of total household income,which means that the degree of part-time employment is high. Of these farmers,13.3%served as village cadres or party members of the CPC (the Communist Party of China).

3.4.Endogenous switching probit model

The endogenous switching probit model consists of a switch (selection) equation and an outcome equation.The switch equation is used to determine the factorsinfluencing Internet use,and the outcome equation is used to determine the impact of Internet use on farmers’adoption of IPM technology. The endogenous switching probit model has advantages over other models,such as the propensity score matching (PSM) model and the recursive bivariate probit (RBP) model,which are commonly used to address selection bias issues. The PSM model’s advantage is that it can control observable heterogeneity,such as the number of households and the area of arable land (Amin and Islam 2022;Guha 2022;Maet al.2022;Minah 2022;Yang and Wang 2023). However,it cannot control unobservable heterogeneity. Although the RBP model can simultaneously control observed and unobserved heterogeneity,it only estimates one selection equation and one outcome equation (Maet al.2020;Ma and Zhu 2021;Liet al.2023). The endogenous switching probit model reduces selection bias by controlling both observed and unobserved heterogeneity,thus relaxing the assumptions of the PSM model. In addition to the selection equation,the endogenous switching probit model estimates two independent outcome equations,which visually display the differences in group decisionmaking between those who use the Internet and those who do not (Lokshin and Sajaia 2011;Abudulai and Huffman 2014;Ma and Abdulai 2016;Maet al.2018;Ma and Abdulai 2019;Haileet al.2020;Liet al.2020).

Table 1 Definition and summary statistics of selected variables

The following model was constructed to identify the factors influencing farmers’ Internet use:

The technology adoption model for farmers is as follows:

The decision-making models of IPM technology adoption for farmers who use the Internet and those who do not use the Internet are as follows:

The treatment effect (TE) is the expected effect of the treatment for the individual with observed characteristicsxrandomly drawn from the population.

The effect of the treatment on the treated (TT),or the expected effect of the treatment on individuals with observed characteristicsxwho used the Internet.

The effect of the treatment on the untreated (TU),which is the expected effect of the treatment on individuals with observed characteristicsxwho did not use the Internet.

The average treatment effects (ATT,ATU,and ATE)for the corresponding subgroups of the population can be calculated by averaging eq.(5) through eq.(7) over the observations in the subgroups. This article aims to analyze the heterogeneity of Internet use on farmers’IPM technology adoption from the perspective of rational inattention. This analysis is based on the premise that the effect of Internet use on different farmers is heterogeneous,and this heterogeneity is related to the way and extent farmers choose to use the Internet.Therefore,it belongs to the category of “Treatment effects are heterogeneous across the study population,and the treatment decision is related to the treatment-effects heterogeneity”. In this case,the ATT/ATE/ATU are often not equal (Fanget al.2012),so only by presenting all three can we fully analyze the heterogeneity of Internet use. What’s more,if this endogenous problem cannot be addressed,the role of Internet use for vulnerable farmers may be overestimated due to the selection bias in ATE/ATU,which may conceal the true reason for the heterogeneity of Internet use.

4.Results and discussion

4.1.Effects of lnternet use on the adoption of lPM by farmers

The LR test for the independence of the two-stage equation in Table 2 shows that the null hypothesisρ1=ρ0=0 can be rejected at the 5% level. This indicates that there are unobservable factors that affect both farmers’ Internet use and the adoption of IPM. Therefore,it is appropriate to choose the endogenous switching probit model. The error term correlation coefficientρ1is significantly negative,suggesting that farmers who actively search for agricultural technology information on the Internet have a higher probability of adopting IPM than the other farmers in our sample.

From Table 3,the average treatment effect (ATE)of Internet use reaches 0.649,indicating that Internet use has a significant effect on farmers’ adoption of IPM technology. Since IPM technology is a typical information-intensive technology and is still in the early stages of diffusion (Ma and Abdulai 2019),sources of social relationships,such as relatives and friends,provide limited information. For farmers,the Internet and otherinformation sources can easily form complementary relationships. Therefore,the Internet has played a significant role in promoting farmers’ decisions to adopt IPM technologies (Cole and Fernando 2021;Akermanet al.2022).

Table 2 The effect of Internet use on integrated pest management (IPM) adoption by farmers

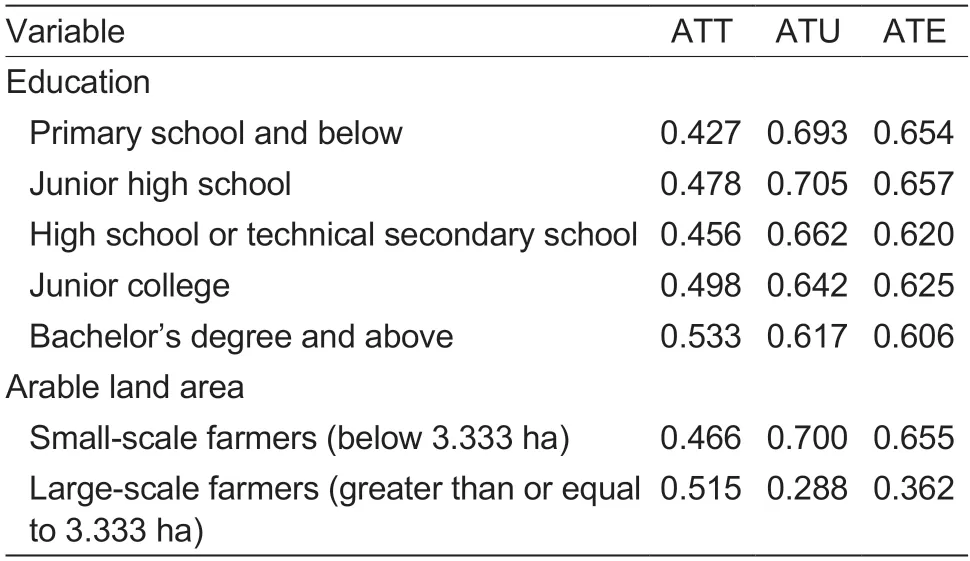

Then,we analyze the difference in the ATE of farmers’Internet use by distinguishing between different education levels and arable land area. The results in Table 4 show that Internet use appears to bring greater technological dividends to farmers with lower levels of education and small-scale farmers,which is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies (Gaoet al.2020;Li B Zet al.2022;Zhenget al.2022;Nguyenet al.2023).These studies generally suggest that small farmers with lower education levels face greater constraints in accessing production technology information when making decisions. As a result,after using the Internet to expand their information sources,their awareness of new technologies and their willingness to adopt them are expected to significantly improve. Specifically,the effect of Internet use is greater in the “primary school and below”group and the “junior high school” group. This indicates that Internet use brings more technological dividends to farmers in the transformation of green production. While farmers in the “undergraduate and above” group benefit the least from Internet use. In addition,it can also be found from the results in Table 4 that the technological dividends obtained by small-scale farmers are higher than those obtained by large-scale farmers.

Please see the significance of the difference in ATT among farmers with different education levels and among farmers with different arable land areas in Appendix B.

However,theT-test shows that there is no significant difference in ATT between farmers with different levels of education and arable land area (Appendix B). From the perspective of technology diffusion theory,the informationintensive IPM technology is still in the initial stage of diffusion,and both vulnerable farmers and other farmers have a limited understanding of technical information. At this time,the role of the Internet in broadening information acquisition channels is very important for all farmers. On the contrary,the disadvantage of vulnerable farmers’learning ability leads to their lower Internet use rate thanother farmers,so vulnerable farmers show higher ATU but lower ATT. This shows that once vulnerable farmers use the Internet,the probability of technology adoption will increase significantly,but in fact,the Internet use of vulnerable farmers is not ideal.

Table 4 Heterogeneity analysis of farmers with different education levels and arable land area1)

The results verified that the ATT/ATE/ATU values are not equal when treatment effects are heterogeneous across the study population,and the treatment decision is related to the treatment-effects heterogeneity. ATE/ATU values of vulnerable farmers are higher than their ATT. If the ATE/ATU values are used to evaluate the technological dividends of the Internet,the positive effect of Internet use will be overestimated due to selection bias.Therefore,it is considered more reasonable to choose the ATT to evaluate the role of Internet use. From the average treatment effect of farmers who use the Internet(Table 4;Appendix B),vulnerable farmers,namely farmers with lower education levels and small-scale farmers,do not benefit more from Internet use. Overall,the considerable selection bias leads to an overestimation of the technological dividends that Internet use brings to vulnerable farmers. This is also verified by the analysis results of farmers’ Internet use decisions. Farmers with a high level of education and learning ability are more willing to consider the Internet as a “new agricultural tool”. The results suggest that farmers’ human capital and technology endowment remain important factors that affect their access to technological dividends (Acemoglu 2002),validating the theory of skill-biased technological change.

4.2.Rational inattention and the heterogeneity of the effects

After analyzing the factors influencing farmers’ Internet use decisions and IPM adoption decisions,the reasons for the heterogeneity of effects of Internet use are further analyzed from the rational inattention perspective. This part aims to reveal why vulnerable farmers fail to obtain more technological dividends.

The results of model (2) in Table 2 show that the area of arable land,sources of information,and political status have a significant effect on the technology adoption of farmers who use the Internet. Among these factors,all types of information sources have a positive impact on farmers’ technology adoption,but only the impact of agricultural inputs suppliers is significant. This is related to the ability of agricultural input suppliers to better integrate external and local information in the early stages of technology diffusion. On the one hand,agricultural inputs suppliers can obtain information about new technologies from upstream manufacturers and pass it to farmers through transactions. On the other hand,they can also effectively integrate the decentralized feedback information on new technology from farmers by leveraging transactions. This enables agricultural input suppliers to have the advantage of information quality in the early stages of new technology diffusion,which significantly impacts farmers’ technology adoption (Zhang and Li 2014).

The area of arable land has a positive impact on the adoption of IPM by farmers in the Internet user group,and this impact is significant at the 10% level,which is consistent with the conclusions of Kabir and Rainis(2015),Ma and Abdulai (2019) and Creissenet al.(2021).This is because some technologies,such as physical pest management technologies,have a threshold for economies of scale,which indicates that the larger the farmers’ land scale,the lower the cost of technology implementation (Wuet al.2018). Moreover,some pests and diseases have apparent spillover effects,and management technologies such as biological management can only be effective if they are used simultaneously on concentrated and contiguous lands (Creissenet al.2021).Therefore,large-scale farmers are more willing to adopt the IPM technology. Village cadres or party members also have a higher probability of adopting technology,which is related to their leading and exemplary roles (Gaoet al.2020;Wachenheimet al.2021).

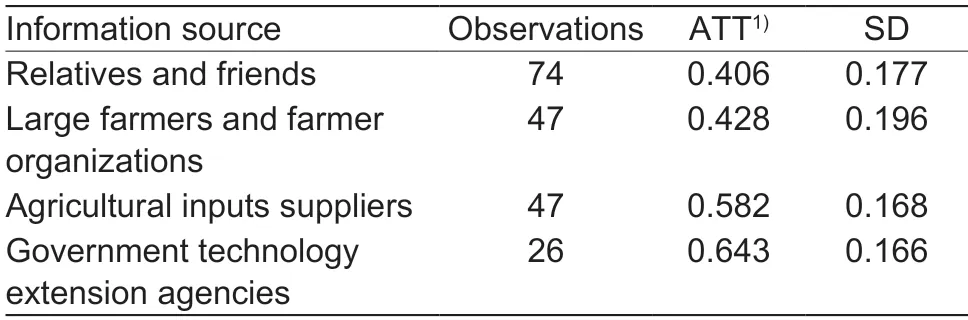

We further analyze the heterogeneity of Internet use on the adoption of IPM from the perspective of rational inattention. The results in Tables 5 and 6 indicate that the effects depend on the farmers’ information sources.The effects are larger for farmers who mainly obtain the information from agricultural inputs suppliers and government agricultural technology extension agencies.The former has been discussed in the second paragraph of this section. A possible reason for government agricultural technology extension agencies is that it is public welfare-oriented,and extension agencies are more specialized. Therefore,the information obtained by farmers from this source is relatively complete and professional,which enables them to have strong information-processing abilities. These results are also consistent with the conclusion of Zhenget al.(2022),who found that small farmers who have received government training have stronger production skills and are,therefore,more likely to adopt new technologies after obtaining more information through the Internet. In terms of information content,the Internet and the government transmit both explicit and general knowledge. Farmers who take government agricultural technology extension agencies as their main information source are more receptive to Internet information. More importantly,the characteristics of the Internet,such as the large scope of information search,low search cost,and convenience,make up well for the shortage of government agricultural extension,thus forming a complementary relationship with it (Ogutuet al.2014). However,farmers who rely on strong-tie social networks such as relatives and friends to obtain agricultural technology information usually make decisions by observing “acquaintances,” resulting in their low trust in Internet information. Most of the information transmitted by strong-tie social networks is processed and filtered. Although this information is more localized and has a greater reference value for similar farmers,it is often homogeneous. This leads to incomplete or even large deviations in farmers’ cognition of technology,whichinduces the over-embedding of technological cognition(Li and Li 2023). As a result,such farmers have a lower degree of acceptance and trust in Internet information and are prone to adopt a rational inattention attitude when making decisions. This is consistent with the findings of Zhaoet al.(2021) that light use of the Internet did not change farmers’ ability to obtain information,human capital,and social capital.

Table 5 Average treatment effects of Internet use on integrated pest management (IPM) adoption by farmers with different information sources

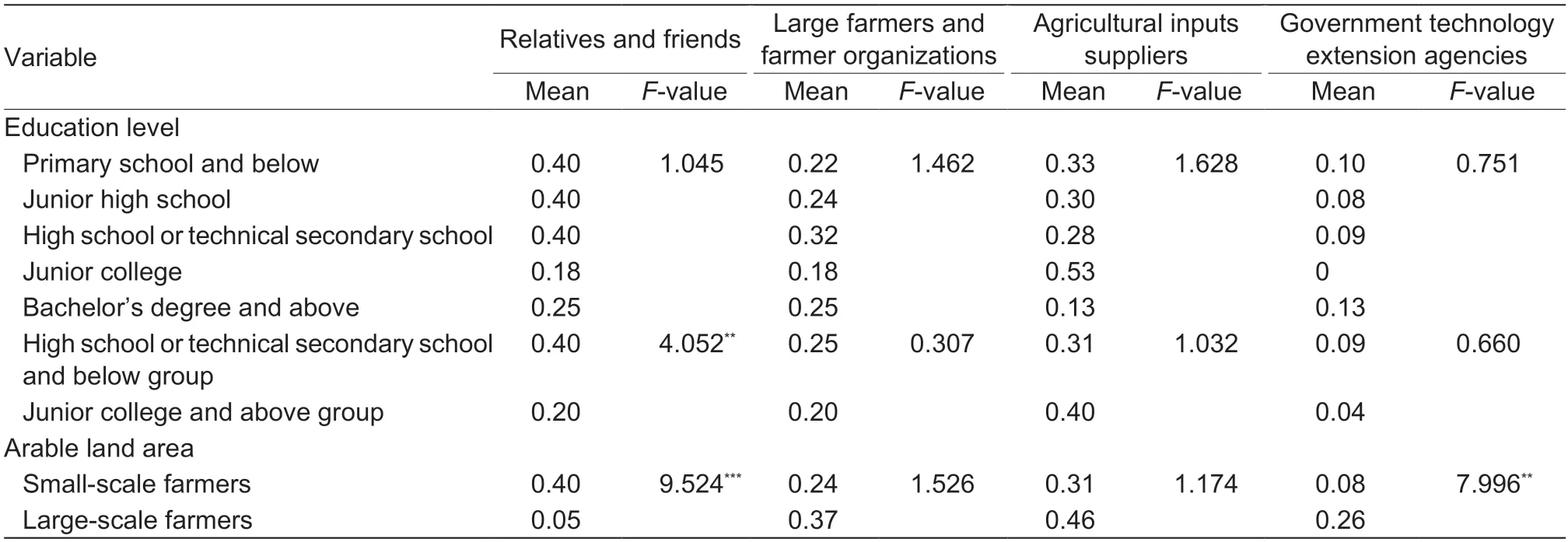

The key reason why vulnerable farmers fail to effectively obtain more dividends from Internet use is their over-reliance on strong-tie social networks. Further analysis reveals that,although there is no significant difference in the main sources of technology information among farmers with different education levels,farmers with lower education levels (high school and below)tended to take relatives and friends as the main sources(Table 7). The difference in information sources between small-and large-scale farmers is even more significant.Small-scale farmers rely more on relatives and friends,while large-scale farmers rely more on government agricultural technology extensions. In general,vulnerable farmers rely more on strong-tie social networks to obtain information,so they tend to adopt a rational inattention attitude toward Internet information. This is the main reason for the inefficient use of Internet information and the difficulty in effectively obtaining Internet technological dividends.

5.Conclusion and policy implications

5.1.Conclusion

Existing studies not only affirm the positive role of the Internet in promoting the transformation of green agriculture but also indicate that vulnerable farmers can obtain more technological dividends. However,this conclusion contradicts the theory of skill-biased technological change. If the conclusion is biased,the problems vulnerable farmers face in green production transformation and Internet use may be ignored. This study theoretically and empirically investigates whether Internet use significantly impacts vulnerable farmers’adoption of green production technology based on a dataset containing 1 015 farmers in Shandong Province,China. From the perspective of rational inattention,the reasons for the heterogeneity effects of Internet use are analyzed,and the potential endogeneity problem is addressed using the endogenous switching probit model.

The main conclusions of this study are as follows.First,Internet use significantly promotes farmers’ adoption of IPM. The ATE of Internet use on farmers’ adoption of IPM technology is 0.649. The results confirm the advantages of Internet use in transmitting technology information,which can encourage farmers to adopt green production technology by reducing the uncertainty of farmers’ decision-making processes.

Second,Internet use provides less technological dividends to vulnerable farmers. Although the ATE is stronger for less-educated and small-scale farmers,these results are from a larger selection bias (namely higher ATU value). By observing the ATT,which can more accurately reflect the promotion effect of Internet use,it becomes evident that vulnerable farmers don’t obtain more technological dividends. Our results demonstrate that farmers’ human capital and technology endowment remain important factors influencing differences in Internet technological dividends.

Third,the difference in technology information sources leads to varying degrees of farmers’ rational inattention to Internet information,which is an important reason for theheterogeneity effect of Internet use. The more farmers rely on strong-tie social networks (e.g.,relatives and friends) for technology information,the less likely they are to trust information from the Internet. In this situation,farmers’ technology cognition is more likely to be trapped in the cocoon of homogeneous information,resulting in over-embedding technology cognition. Therefore,farmers are more inclined to adopt a rational inattention attitude toward Internet information with a high degree of heterogeneity,which weakens the effect of Internet use.Vulnerable farmers receive fewer technological dividends mainly because of their increased reliance on strong-tie social networks for technology information.

Table 7 Differences in technology information sources among farmers with different education levels and arable land areas

5.2.Policy implications

Being trapped in the information cocoons of strongtie social networks and adopting a rational inattention attitude toward Internet information are crucial factors in vulnerable farmers’ inability to obtain the dividends of Internet use effectively. Therefore,to better play the positive role of Internet use in promoting green transformation in agricultural production,it is essential to focus on enhancing vulnerable farmers’ ability to use the Internet and technology information sources.

First,the ability of vulnerable farmers to use the Internet must be improved. On the one hand,training for vulnerable farmers in Internet use should be reinforced through various channels such as WeChat,Tik Tok,and Kuaishou. On the other hand,efforts should be made to strengthen the development of agricultural technology information platforms. Technology information related to major local industries and products should be effectively gathered and verified. By improving the localization of information,trust in Internet sources among vulnerable farmers can be increased,and the challenges associated with accepting Internet information can be reduced.

Second,it is necessary to encourage farmers with strong Internet utilization ability to share technology information actively,optimizing the source of technology information for vulnerable farmers. Providing free training and establishing farmer-expert WeChat groups can better address the agricultural technology needs of farmers with strong ability of Internet use. Moreover,by providing incentives such as free production materials and mobile data,farmers with strong Internet utilization skills can be guided to share new technology information with their neighboring vulnerable farmers actively.

5.3.Limitations

There are still a few limitations in our study. First,our study only captured IPM adoption and internet use using dummy variables without considering the intensity of internet use on IPM adoption. Second,due to the limitation of cross-sectional data,it is difficult for this paper to discuss the impact of Internet use on farmers’ IPM adoption in the long run. Since the degree of dependence on the Internet may vary among rural households who use the Internet for different periods,there may be a lag in the impact of Internet use on rural households. However,the limitation of cross-sectional data prevents us from identifying this lagged effect,leading to the possible underestimation of Internet use’s effect. Therefore,further research could focus on collecting longer-term data to refine our analysis and capture the long-term impact of Internet use on farmers’ IPM adoption.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (20CGL027).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.08.005

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- The association between the risk of diabetes and white rice consumption in China: Existing knowledge and new research directions from the crop perspective

- Linking atmospheric emission and deposition to accumulation of soil cadmium in the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain,China

- Genome-wide association study for numbers of vertebrae in Dezhou donkey population reveals new candidate genes

- lnfluences of large-scale farming on carbon emissions from cropping:Evidence from China

- Spatio-temporal variations in trends of vegetation and drought changes in relation to climate variability from 1982 to 2019 based on remote sensing data from East Asia

- Optimizing water management practice to increase potato yield and water use efficiency in North China