Histone H3K27me3 methylation regulates the expression of secreted proteins distributed at fast-evolving regions through transcriptional repression of transposable elements

XIE Jia-hui ,TANG Wei ,LU Guo-dong, ,HONG Yong-he# ,ZHONG Zhen-hui# ,WANG Zong-hua,,ZHENG Hua-kun,#

1 State Key Laboratory of Ecological Pest Control for Fujian and Taiwan Crops,College of Plant Protection,Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University,Fuzhou 350002,P.R.China

2 Fujian Universities Key Laboratory for Plant Microbe Interaction,College of Life Sciences,Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University,Fuzhou 350002,P.R.China

3 Fuzhou Institute of Oceanography,Minjiang University,Fuzhou 350108,P.R.China

4 National Engineering Research Center of JUNCAO Technology,College of Life Science,Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University,Fuzhou 350002,P.R.China

Abstract The fine-tuned expression dynamics of the effector genes are pivotal for the transition from vegetative growth to host colonization of pathogenic filamentous fungi. However,mechanisms underlying the dynamic regulation of these genes remain largely unknown. Here,through comparative transcriptome and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing(ChIP-seq) analyses of the methyltransferase PoKmt6 in rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae (syn.Magnaporthe oryzae),we found that PoKmt6-mediated H3K27me3 deposition was enriched mainly at fast-evolving regions and contributed to the silencing of a subset of secreted proteins (SP) and transposable element (TE) families during the vegetative growth of P.oryzae. Intriguingly,we observed that a group of SP genes,which were depleted of H3K27me3 modification,could also be silenced via the H3K27me3-mediated repression of the nearby TEs. In conclusion,our results indicate that H3K27me3 modification mediated by PoKmt6 regulates the expression of some SP genes in fast-evolving regions through the suppression of nearby TEs.

Keywords: secreted protein,transposable elements,fast-evolving regions,H3K27me3

1.Introduction

The fine-tuned,stage-specific expression of effector genes is pivotal for the infective development of pathogenic fungi,which has resulted in massive agricultural yield losses worldwide. To colonize their host or control the transition from biotrophic to necrotrophic infection,filamentous fungal pathogens secrete large amounts of effectors that target various host cell compartments during infection (Djameiet al.2011;Rovenichet al.2014;Rodriguez-Morenoet al.2018;Liet al.2020). The majority of identified effectors are small SPs,which are transcriptionally activated during infection.The coding genes of these SPs are preferentially distributed in transposable element (TE)-rich regions,the so-called fast-evolving regions (Schmidt and Panstruga 2011;Giraldoet al.2013). However,since most of TEs were accumulated in compacted heterochromatin regions that were inactivated by repressive epigenetic marks (Seidl and Thomma 2017),genes nearby were also silenced because of the position effects. Once the repressive chromatin state of TEs were lifted,the repression on the nearby genes was also released (Rebolloet al.2012).Therefore,the proximity to TEs may impose additional transcriptional regulation machinery on SP genes within the fast-evolving regions.

Previous studies in fungal pathogens indicated that the transcription of effector/pathogencity-associated genes(PAGs) are epigenetically silenced during vegetative growth (Gacek and Strauss 2012;Connollyet al.2013;Chujo and Scott 2014;Soyeret al.2014;Studtet al.2016,2017;Dalleryet al.2017;Meileet al.2020). The activation of thesePAGs after decompaction of chromatin during infection by recruiting transcription factors,such as the Sge1/Ros1 orthologs and the AbPf2 orthologs are also essential for the regulation of fungal effectors (Choet al.2013;Santhanam and Thomma 2013;Gohariet al.2014;Ökmenet al.2014;Dalleryet al.2017;Rybaket al.2017). Trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27(H3K27me3) catalyzed by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) subunit KMT6 is one of the major modifications associated with facultative heterochromatin and the transcriptional repression ofPAGs (Jamiesonet al.2013). For example,the homologs of Kmt6 are crucial for the silencing of effector genes inUstilaginoidea virens(Menget al.2021),as well as the secondary metabolite genes (SMGs) inFusariumgraminearumandFusariumfujikuroi(Connollyet al.2013;Studtet al.2016;Freitag 2017). InEpichloëfestucae,EzhB(KMT6 homolog)-mediated H3K27me3 cooperates with H3K9me3 to repress the alkaloid bioprotective metabolite genesinvitro(Chujo and Scott 2014). InPhytophthora sojae,H3K27me3 mediates the silencing ofAvr1bto avoid immunity recognition by the soybean Rps1b protein(Wanget al.2020).

Pyriculariaoryzae(syn.Magnaportheoryzae) infects many grasses and causes blast disease on economically important crops such as rice and wheat (Deanet al.2012;Islamet al.2016). In order to colonize the host,the rice blast fungus secretes hundreds of apoplastic effectors to Extra-Invasive Hyphal Membrane (EIHM) or cytoplasmic effectors into plant cells through Biotrophic Interfacial Complex (BIC) during infection (Giraldoet al.2013;Giraldo and Valent 2013). Accumulating evidence suggests that most of these effector genes are silenced during vegetative growth and are specifically derepressed during the interaction with plants (Mosqueraet al.2009;Yoshidaet al.2009;Saitohet al.2012;Chenet al.2013;Nishimuraet al.2016;Guoet al.2019). A recent study revealed the important role of Kmt6-mediated H3K27me3 deposition in transcriptional repression of effector genes during vegetative growth inM.oryzae(Zhanget al.2021). Moreover,the additional PRC2 subunits,P55 and the Sin3 histone deacetylase complex,are required for the proper distribution of H3K27me3 to maintain stable transcriptional silencing (Linet al.2022). These results illustrated that the deletion of H3K27me3 in fungus can affect gene expression levels. What is not yet clear is how H3K27me3 regulates the expression of fast-evolving SP genes that were depleted of H3K27me3 but distributed closely with TEs. In this study,we aimed to explore the role of TEs in H3K27me3-mediated transcriptional regulation of SP genes enriched around TEs. We found that some silenced SP genes were indirectly repressed by H3K27me3 through the modification of the nearby TEs within the fast-evolving regions.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Targeted gene deletion of PoKmt6 and complementation of PoKmt6

To generate ΔPokmt6mutants,a 1 180-bp upstream fragment (A) and a 1 101-bp downstream fragment (B) of the targeted open reading frame (ORF) were amplified from Guy11 genomic DNA using the primer setsKMT6AF&KMT6AR,andKMT6BF&KMT6BR,respectively.The purified PCR products were then fused with the N-terminal (HY) and C-terminal (YG) of the hygromycin B phosphotransferase cassette (HPH) to form the ‘A–H’ and‘H–B’ fusions,respectively (Appendix A). The ‘A–H’ and ‘H–B’ fusions were transformed into the protoplasts of Guy11 through polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation,according to previous research (Kershaw and Talbot 2009). To identify the targeted gene deletion mutants,all hygromycin-resistant transformants were first screened by PCR-based genotyping using primersKMT6tF&KMT6tFandKMT6UAF&H853. The positive transformants were further confirmed through a Southern hybridization assay.

For complementation assay of ΔPokmt6,a 6.1-kb genomic DNA fragment containing the native promoter,CDS region,and 3´-UTR ofPoKmt6was amplified using primers setsKMT6comslF&KMT6comslRand ligated into the pKNTG plasmid. The obtained construct was transferred into ΔPokmt6through PEG-mediated transformation (Kershaw and Talbot 2009). The neomycin-resistant transformants were verified through PCR-based genotyping. All primers sequences are available at Appendix B.

2.2.Southern hybridization assay

A total of 10 µg genomic DNA from each strain was digested withKpnI. Digested products were electrophoreced in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and then transferred into positively charged nylon membranes(Roche Diagnostics GmbH,Germany). A specific hybridization probe was amplified by using the primers setsKMT6BF&KMT6BR. We performed probe labelling,hybridization and detection experiments through using DIG High Prime DNA Labelling and Detection Starter Kit I(Roche),following the instruction manual.

2.3.RNA extraction,cDNA library preparation,and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

All strains were maintained at 28°C on complete medium(CM;0.6% yeast extract,1% sucrose,0.6% tryptone) for 3 days and then collected mycelium in liquid nitrogen.For infection assay,conidial suspensions (1×105conidia mL–1in 0.025% Tween-20 solution) of each strain were used to inoculate the 14-day-old susceptible line CO39.The culture condition,plant inoculation and subsequent incubation of rice plant are same as described previously(Giraldoet al.2013). Sample was collected at 0,24,48 and 72 h after inoculation,respectively. Total RNA was extracted from each sample using the Eastep Super Total RNA Extraction Kit (Promega,USA). The synthesis and qRT-PCR of first strand cDNA were conducted as described previously (Wu C Xet al.2021). The designed primers for qRT-PCR as listed in Appendix C.

2.4.Western blot assay

Extraction of proteins was performed as described (Honda and Selker 2008). After the separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE),proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride(PVDF) membranes (Merck Millipore Ltd.,USA). After incubation with anti-H3K27me3 (Active Motif 39537)and anti-H3 (Histone H3 Antibody #9715) antibodies,respectively. The Western Bright ECL HRP substrate(Advansta,Menlo Park,CA,USA) was used to identify the chemiluminescent signals from the membranes.

2.5.RNA sequencing

The total RNA of each sample with at least two independent biological replicates were used for the construction of the RNA-seq library,following the procedures described previously (Zhonget al.2019).These libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System (Illumina,CA,USA).

2.6.RNA-seq data analysis

Quality assessment of raw reads (RNA-seq) was performed using FASTQC v0.11.3 (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/bugzilla/). Adapters of reads were removed using Trim_galore v3.1 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore/). RNA-seq reads were aligned to 70–15 reference genome sequence (Deanet al.2005)using RSEM v1.3.3 (Li and Dewey 2011). Expression counts were quantified with transcript per million (TPM).The procedure of searching TEs and secreted proteins was conducted as described previously (Zhonget al.2020).

2.7.ChIP-seq analysis

ChIP-seq data ofM.oryzaemycelium (Zhanget al.2021) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) Database. The pipeline of analysis followed the methods from zhanget al.(2021). To analyze H3K27me3,the reads in aligned bam files were calculated by Perl scripts and were normalized with reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (RPKM).

2.8.Statistical analysis and plots

Statistical analysis was conducted by R packages in the R studio (version 1.4.1106) environment. In RNAseq results,differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by the edgeR package (Robinsonet al.2010)and combination plots by ggplot2 (Gómez-Rubio 2017).

3.Results

3.1.PoKmt6-suppressed genes are enriched in the fast-evolving regions

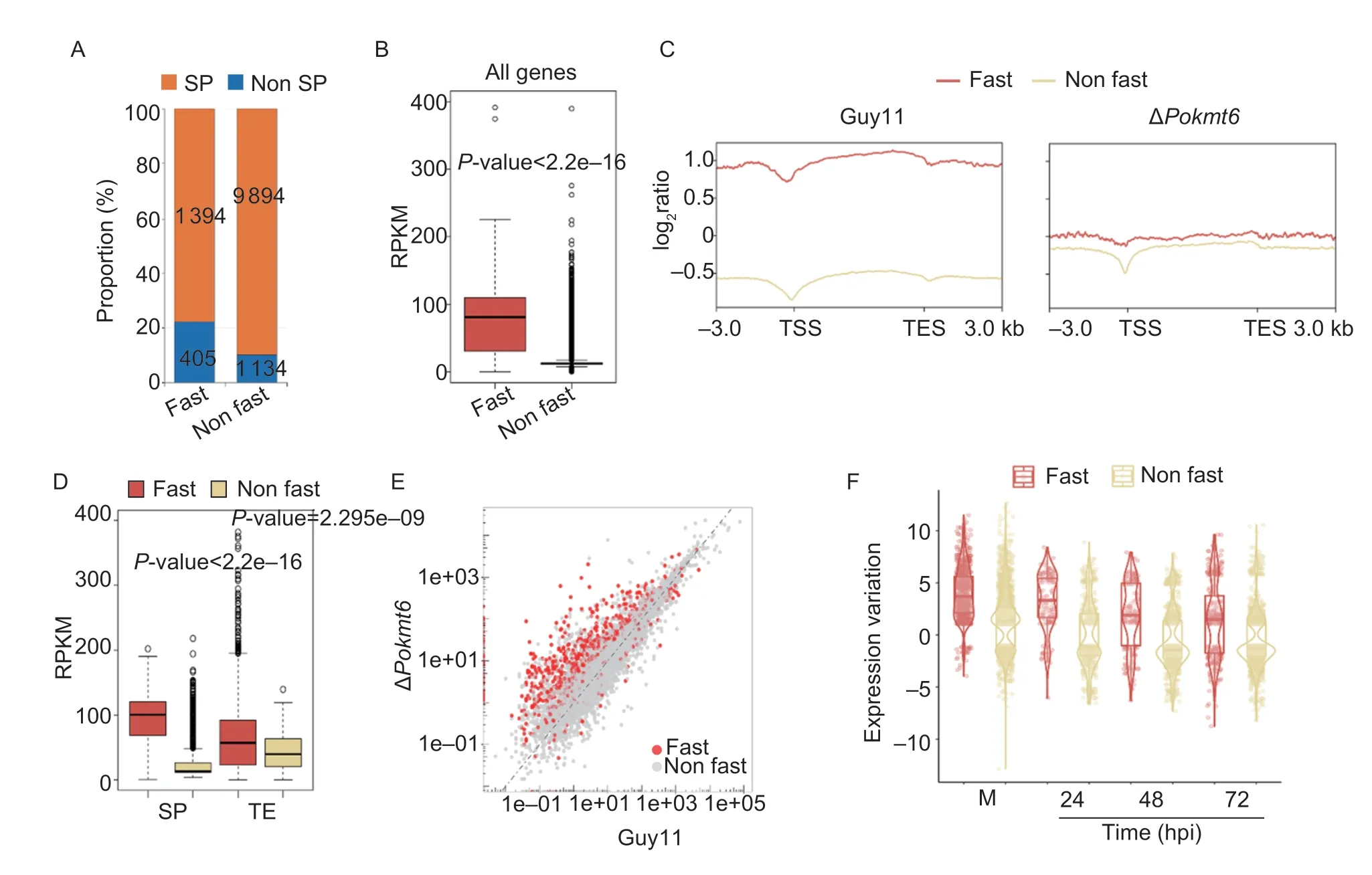

Genomic sequences of many fungal pathogens could be defined into two major types: 1) gene sparse,repeat-rich(fast-evolving) regions;and 2) gene dense,TEs poor (non fast-evolving) regions (Donget al.2015). Based on the content of transposon elements,we divided the genome ofP.oryzaeinto 139 fast-evolving (~8 Mb,average size 57.5 kb),and 146 non fast-evolving regions (~33 Mb,average size 226.2 kb). Compared with the non fastevolving region,there were more abundant TEs,and a higher proportion of secreted protein genes in the fastevolving regions (Fig.1-A). We then compared the H3K27me3 signals between fast-evolving regions and non fast-evolving regions and observed significantly higher signals of H3K27me3 over fast-evolving regions (P<2.2e–16;Fig.1-B). Interestingly,the levels of H3K27me3 on SP genes and TEs were higher in fast-evolving regions than in non fast-evolving regions (Fig.1-C and D).

Fig.1 PoKmt6 repression of gene expression has primarily occurred in fast-evolving regions. A,the bar plot shows the proportion of secreted proteins (SP) (blue) and non SP (yellow) in fast-evolving regions (fast) and non fast-evolving regions (non fast). B,the boxplot shows the level of H3K27me3 in two regions (Wilcoxon test,P-value<2.2e–16). Colored boxes indicate two different regions defined in the current study. C,ChIP-seq signal profile of H3K27me3 on genes in two types of regions.–3.0 kb indicates the upstream 3.0 kb of transcriptional start sites (TSS),and 3.0 kb indicates the downstream 3.0 kb of transcriptional end sites (TES).D,the boxplot shows the level of H3K27me3 in SP (Wilcoxon test,P-value<2.2e–16) and TEs (Wilcoxon test,P-value=2.295e–09),respectively. In the boxplot,the black line in the central represents median value and the uppper and lower quartiles of the box indicate 75th and 25th percentiles,respectively. The whiskers from the edge of box extend to the most extreme data points,which are no more than 1.5 times the interquartile range of the box. These parameters are applied to all boxplots in the current study. E,a scatter plot of RNA-seq expression data shows expression comparison of the wild-type strain (Guy11) and ΔPokmt6 in vegetative growth. The red dot represents genes in fast-evolving regions. The grey dot represents genes in non fast-evolving regions. F,the boxplot shows the fold change of differentially expressed genes in distinct regions throughout entire life-cycle. hpi,h post-inoculation.

KMT6 homolog in wheat blast fungus is involved in development,conidiation,and pathogenicity (Phamet al.2015),which is partially consistent with the role of KMT6 inP.oryzae(Wu Z Let al.2021;Zhanget al.2021). To investigate the regulatory mechanism regarding gene suppression ofPoKmt6in detail,we first generated a knockout mutant ofPoKmt6(MGG_00152) (Phamet al.2015),using the split marker approach (Appendix A).ThePoKmt6null strains were identified through PCRbased genotyping,and further confirmed with Southern blot analysis and Western blot experiments (Appendix A). Next,to investigate how PoKmt6 was involved in finetuned dynamic transcription processes in two regions,we performed a comparative transcription study of samples obtained growing in complete media (M) and at 24,48,and 72 h post-inoculation (hpi). A scatter plot displaying the expression value of all genes in the wild type and mutant isolates indicated that the majority of the genes located in fast-evolving regions were up-regulated in the mutant during vegetative growth (Fig.1-E). We also counted the fold-change (FC) of DEGs in two regions,and discovered that the level of up-regulation was more evident on genes from fast-evolving regions (Fig.1-F).We performed qRT-PCR to validate the expression of several putative SP genes. The results showed that the relative transcription level of all the SP genes tested was up-regulated in the mutant strain,which is consistent with RNA-seq results (Appendix D). Taken together,we conclude thatPoKmt6-mediated H3K27me3 mainly inhibited genes belonging to fast-evolving regions.

3.2.PoKmt6 transcriptionally represses different TE families in a stage-specific manner

To assess whetherPoKmt6is also involved in the transcriptional repression of TEs during vegetative growth and infection,we compared the transcript abundance of TEs between the wild-type and ΔPokmt6strains.Among 12 TE families investigated,we found that DNA transposonPOT3showed up-regulated transcription levels in ΔPokmt6under bothinplantaand vegetative growth conditions but was down-regulated at 48 hpi.While long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposonsRETRO6andMGL3were increased exclusively during asexual development. The rest of TE families remained largely unalteredin vitroor even down-regulatedinplanta(Fig.2-A–D). Collectively,PoKmt6inhibitedPOT3during vegetative growth and infection stages.

Fig.2 Derepression of transposable elements (TEs) in ΔPokmt6. Boxplots show the expression levels of 12 TE families in wildtype (green box) and ΔPokmt6 (purple box) during vegetative growth (mycelium,M) and invasive growth at 24,48 and 72 h postinoculation (hpi),respectively. A,TEs expression in vitro growth. B to D,TEs expression at different collected time points during planta growth,respectively.

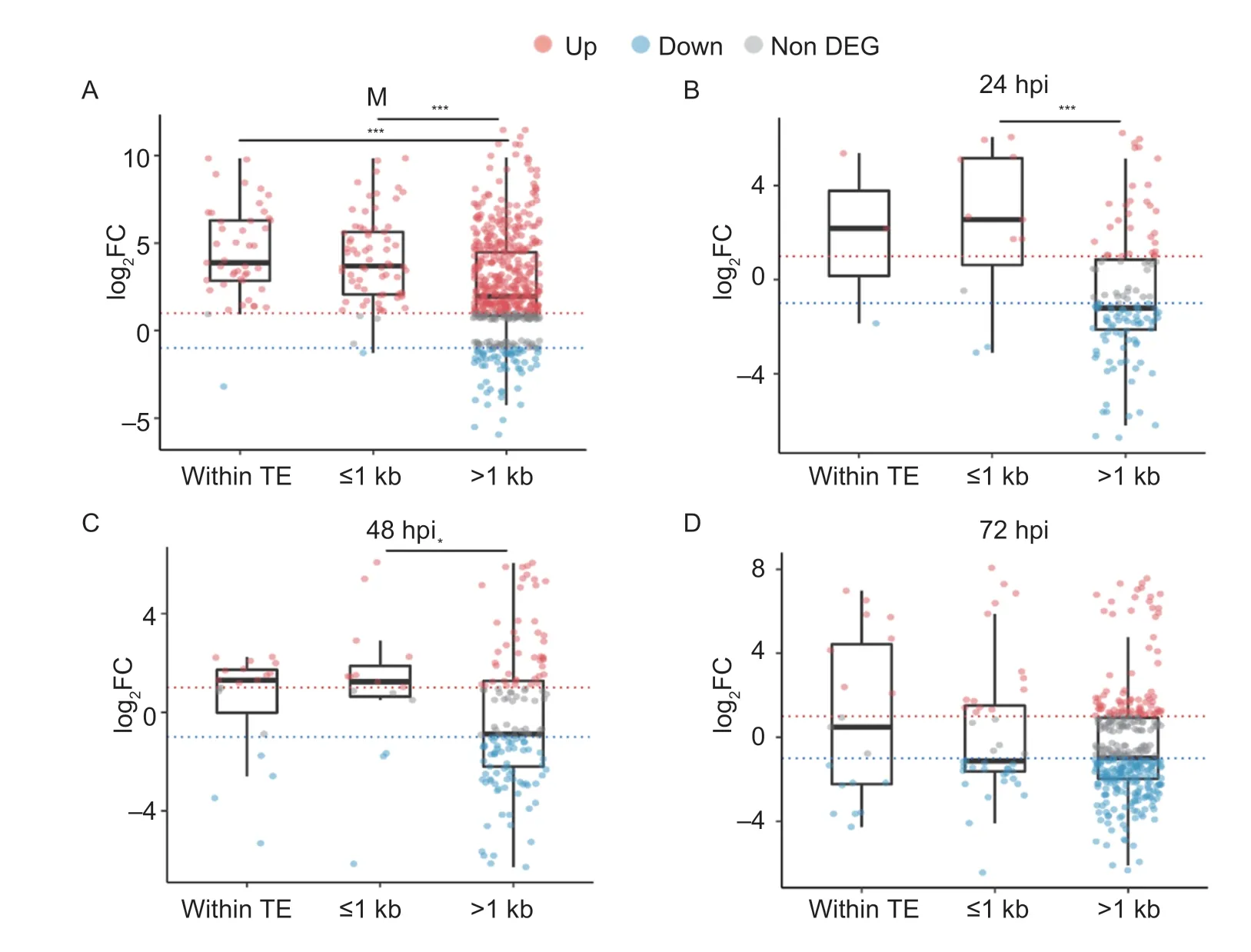

3.3.The transcriptional silencing effect of PoKmt6 was influenced by TEs location

TEs are the major target of epigenetic modification and possess a proximity effect on gene expression (Fouchéet al.2020),thus we studied the effect of TEs location to understand transcriptional suppression effect ofPoKmt6on SP genes. Initially,we divided the SP genes into three groups according to their distance to the TE nearby: group 1,SP genes with a TE in coding regions;group 2,SP genes with a TE≤1 kb from start codon;and group 3,SP genes with a TE>1 kb from start codon. We performed a comparative analysis of the transcription level of SP genes and marked significant differentially expressed SP genes (DESPs)from the three groups. The results indicated that,the fold change ofDESPin group 3 significantly different from other groups during vegetative growth andinplantagrowth,except for 72 hpi. Moreover,most SP genes were significantly up-regulated for both group 1 and group 2,while the number of up and downregulated genes was equivalent at 72 hpi. However,in group 3,the number of up-regulated SP genes was higher only in vegetative growth and more genes were downregulated during infection (Fig.3). The above results suggested that TEs affected the degree of repression byPoKmt6methyltransferase in the genomic region.

Fig.3 Secreted proteins (SPs) gene expression level as functions of different distances away from transposable elements(TEs). A,log2FC of DESPs during vegetative growth (mycelium,M). B to D,DESPs collected at different times during infection,respectively. hpi,h post-inoculation. DEG,differentially expressed genes. Boxplots show log2FC of significant DESPs in various genomic regions when cultured in media and infecting the host. The red line (log2FC=1) and the blue line (log2FC=–1) distinguish significantly up-regulated SP genes (red dots) and down-regulated SP genes (blue dots),respectively. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*,P-value<0.05;**,P-value<0.01;***,P-value<0.001).

3.4.PoKmt6 regulates SP gene expression through H3K27me3 deposition of their nearby TEs during vegetative growth

To investigate the preference of H3K27me3 marks distribution in genomic regions,we analyzed the number of marks on different types of genes in two regions.We discovered that there were more H3K27me3 modified SP genes in fast-evolving regions than in non fast-evolving regions (34.07%vs.11.46%),and the same situation occurred in other genes (27.83%vs.3.70%). Interestingly,despite high level of H3K27me3 modifications over fast-evolving regions,we observed that more SP genes at fast-evolving regions were not modified by H3K27me3 (65.93%vs.34.07%) (Fig.4-A).We further focused on the histone marks onDESPs,and observed that more up-regulated SP genes (68.89%)were not modified than modified (31.11%) in fastevolving regions,which also occurred in non fast-evolving regions (Fig.4-B). According to the biased distribution of H3K27me3 marks,we hypothesize that SP genes that are up-regulated but not modified by H3K27me3 in fastevolving regions are caused by adjacent TEs. Therefore,we next determined the levels of H3K27me3 on these adjacent TEs (within 1 kb from SP genes) in two regions,and found that these TEs had higher levels of H3K27me3 in fast-evolving regions (Fig.4-C). For example,the SP gene,MGG_09404,was depleted of H3K27me3 over gene body,whereas the nearby TE (SINE) was modified by H3K27me3. We found thatMGG_09404was transcriptionally activated in ΔPokmt6during vegetative growth in the absence of H3K27me3 over TE located at its promoter region (Fig.4-D). These results support the hypothesis thatPoKmt6regulates SP gene expression indirectly by depositing H3K27me3 on nearby TEs.

Fig.4 H3K27me3 methylation on different types of genes. A,the bar plot shows the proportion of H3K27me3-marked genes(transposable elements (TEs),secreted secreted proteins (SPs),and other genes). B,the proportion of histone marks of DESPs in different regions. C,boxplot shows the level of H3K27me3 of TEs within 1 kb surrounding unmodified and up-regulated SP genes(Wilcoxon test,P-value=0.02886). D,a screenshot shows an example of the re-activation of a SP gene. In ChIP-seq profiles,the red and blue bar tracks indicate wild-type and mutant,respectively. The green bar track represents the wild-type and the red bar track represents the mutant in RNA-seq results.

4.Discussion

We separated genomic regions according to TEs content to explore the role of TEs in the H3K27me3-mediated repression of SP genes. We combined genome-wide transcription with ChIP-seq analyses to determine the main repression region of SP genes by H3K27 methylation inP.oryzae. Moreover,we identified the role of TEs in H3K27me3 silencing of SP genes.

The two-speed genome separates the filamentous fungal genome into two compartments: the gene poor regions (TA-rich or repeat-rich) mainly encode the effector/pathogenicity-associated genes and the generich region mainly encodes the housekeeping genes.The two-speed genome has at least two functions: (1)evolutionary protection of basic genes from high rates of deleterious mutations while effector genes undergo rapid evolutionary change (Croll and McDonald 2012;Sánchez-Valletet al.2018);(2) transcriptional silencing of genes by forming facultative heterochromatin,which is considered to be more effective than the transcriptional repression of individual genes in euchromatin (Gacek and Strauss 2012;Soyeret al.2014). Although fungal pathogens apply facultative heterochromatin to control the transcription of pathogenicity-associated genes (PAGs),different fungal gene clusters may involve different chromatin-based regulatory systems to fine-tune these genes (Connollyet al.2013;Soyeret al.2014;Sánchez-Valletet al.2018). Trimethylation at lysine 27 of histone H3 had been proved to be involved in the stage-specific silencing ofPAGs in many fungal species,such as the SMGs inFusariumgraminearum(Connollyet al.2013),as well as the effector genes inZymoseptoriatritici(Meileet al.2020) andUstilaginoideavirens(Menget al.2021). Consistently,H3K27me3 was also required for the transcription repression of part of the SP genes inP.oryzaeduring vegetative growth. By comparing the H3K27me3 methylation level between fast-evolving regions and non fast-evolving regions,we found that this modification is enriched mainly in fast-evolving regions. After deleting genome-wide H3K27me3 marks,we found that genes were up-regulated genome-wide particularly in vegetative growth. Furthermore,epigenetic landscape changes in the genome induced TEs de-repression (Kasuga and Gijzen 2013;Hosaka and Kakutani 2018). We also investigated the impact of H3K27me3 on TEs expression. The results indicated that H3K27me3 modification could repressPOT3families in vegetative growth andinplanta.RETRO6andMGL3families were repressed just in vegetative growth.Previously,H3K27me3 was reported to inhibit TEs activity in unicellular organisms and play a role in suppressing the expression of protein-coding genes in multicellular organisms (Slotkin and Martienssen 2007;Délériset al.2021). Here,H3K27me3 could be involved in regulating TEs and was distributed mainly on repeat sequences sinceP.oryzaeexpands by clonal reproduction (Latorreet al.2020).

Additionally,TEs insertion in the promoter region of genes results in disrupted gene expression patterns of these genes (Castaneraet al.2016). For instance,RNA polymerase can read through TEs and neighbouring genes(Slotkin and Martienssen 2007),or TEs can alter nearby chromatin states and form compacted heterochromatin(Seidl and Thomma 2017). Although the positional effect of TEs was known in regulating gene expression,the mechanism underlying the epigenetic regulation of SPs remained poorly understood. Here,we investigated the connections of TEs and H3K27me3 mediated silencing of SP genes. As SP genes near TEs were more strongly repressed by H3K27me3 in all developmental stages,we deduced that TEs may also have effects on the repression of H3K27me3-mediated silencing of SP gene expression.Here,we found that the majority of H3K27me3 marks were detected on TEs (689) while relatively small amount was detected on SP genes (138) in fast-evolving regions.After deletion of H3K27 methylation from the pathogen genome,many non-modified SP genes were up-regulated in the mutants,suggesting SP genes could be silencedviathe H3K27me3 mediated repression of the nearby modified TEs in fast-evolving regions. However,in non fast-evolving regions,some unknown mechanisms may help H3K27 methylation repress SP genes. Recent study suggested that H3K27me3 deletion could lead to genomewide changes of other histone marks (Zhanget al.2021),which may activate SP gene expression in non fastevolving regions. Here,our results demonstrated that SP genes localized in fast-evolving regions indirectly regulated by PoKmt6-mediated modifications of H3K27me3. These results provide insight into the diverse transcriptional repression of SP genes in the fungal pathogens.

5.Conclusion

Our results suggested that the PoKmt6-mediated H3K27me3 was enriched mainly in fast-evolving regions and was required for silencing of a bunch of SP genes and TE families during asexual growth. We also identified some H3K27me3 unmarked SP genes silencedviaH3K27me3 methylation over nearby TEs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1805232,31770156,and 32172365) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M690637).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.01.011

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年10期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- The association between the risk of diabetes and white rice consumption in China: Existing knowledge and new research directions from the crop perspective

- Linking atmospheric emission and deposition to accumulation of soil cadmium in the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain,China

- Genome-wide association study for numbers of vertebrae in Dezhou donkey population reveals new candidate genes

- Are vulnerable farmers more easily influenced? Heterogeneous effects of lnternet use on the adoption of integrated pest management

- lnfluences of large-scale farming on carbon emissions from cropping:Evidence from China

- Spatio-temporal variations in trends of vegetation and drought changes in relation to climate variability from 1982 to 2019 based on remote sensing data from East Asia