Acute pancreatitis in liver transplant hospitalizations: Identifying national trends, clinical outcomes and healthcare burden in the United States

Dushyant Singh Dahiya, Vinay Jahagirdar,Saurabh Chandan, Manesh Kumar Gangwani,Nooraldin Merza,Hassam Ali, Smit Deliwala,Muhammad Aziz, Daryl Ramai, Bhanu Siva Mohan Pinnam, Jay Bapaye,Chin-ICheng, Sumant Inamdar,Neil R Sharma,Mohammad Al-Haddad

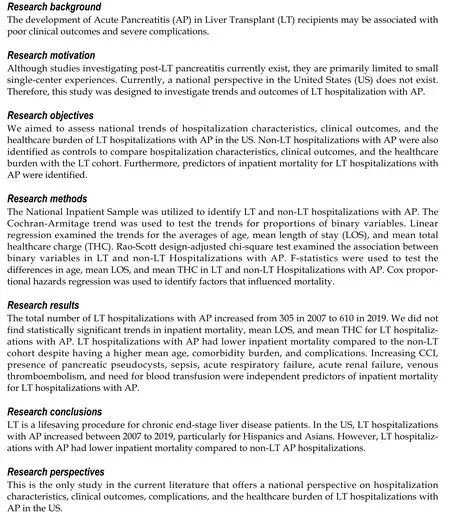

Abstract

Key Words: Liver transplantation; Pancreatitis; Mortality; Cost; Length of stay

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP), an inflammatory response to injury of the pancreas, is one of the leading causes of hospitalization amongst gastrointestinal disorders in the United States (US).In the general population, the incidence of AP is estimated to be 40-50 per 100000 persons and there are approximately 275000 AP hospitalizations annually in the US[1,2].Risk factors implicated in the development of AP include cholelithiasis, heavy alcohol use (4-5 drinks daily for > 5 years), hypertriglyceridemia (> 1000 mg/dL), smoking, medications, autoimmune diseases, genetic predispositions, blunt/penetrating abdominal trauma, viral infections, and therapeutic endoscopic procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), among others[3-10].The pathogenesis of AP is multifactorial, but ultimately involves the unregulated activation of proteolytic enzymes within the pancreas eventually leading to pancreatic ductal obstruction, subsequent inflammation, and in severe cases a systemic-inflammatory response syndrome[11].The characteristic clinical features of AP include nausea,vomiting, loss of appetite, and epigastric abdominal pain radiating to the back[12].A diagnosis of AP can be established by the presence of any two of the following three criteria: (1) Characteristic epigastric abdominal pain; (2) serum lipase and/or amylase greater than three times the upper limit of normal;and (3) evidence of AP on abdominal imaging[13].Over the years, AP hospitalizations are on a rise in the US, with mortality rates ranging from 1%-2% and over 2.5 billion dollars being spent annually on healthcare costs[1,14].

Liver transplant (LT) has revolutionized management for chronic end-stage liver disease with excellent results.Since the first LT in 1967, the procedure has saved close to 500000 Life-years among patients with acute fulminant hepatic failure, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and end-stage liver disease[15,16].The recipients of the procedure have excellent survival rates.Per the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data, the overall patient survival rate after deceased donor LT was 90% and 77%at 1 year and 5 years, respectively[17].Moreover, the graft survival rate at 1 year and 5 years after LT was noted to be 89.6% and 72.8%, respectively[18].

AP is an important risk factor for poor surgical outcomes in patients with LT.Studies have reported an incidence rate ranging from 3%-8% for post-LT pancreatitis[19,20].Common risk factors implicated in the development of post-LT pancreatitis include hepatitis B infection as an indication of transplant,re-transplantation, duration of venous bypass, hypotension with longer procedural time, utilization of ERCP, type of biliary reconstruction, intraoperative calcium chloride administration, and use of an aorto-hepatic graft[19,21,22].Additionally, surgical manipulation, immunosuppression, infections, and biliary complications before LT may also increase the risk of developing post-LT pancreatitis[23].In LT recipients, peri-transplant pancreatitis is associated with a two-fold increased risk of mortality[24].Furthermore, early AP in LT recipients (within 1-2 mo of LT) may have mortality rates as high as 67%[25].Given the acute-organ shortage worldwide, we must identify LT hospitalizations at high risk of developing AP to maximize patient survival.

Although studies investigating post-LT pancreatitis currently exist, they are primarily limited to small single-center experiences[19,20,22,25-27].Hence, this study was designed to investigate trends in hospitalization characteristics and clinical outcomes for LT hospitalizations with AP.Furthermore, we performed a comparative analysis between LT and non-LT hospitalizations with AP to determine the influence of LT on clinical outcomes and healthcare burden.Predictors of inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP were also identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design and data source

This retrospective study derived the study population from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) for 2007–2019 which was coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9thand 10thRevision,Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10- CM) diagnosis codes, and procedure codes.The NIS, maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), is one of the largest, publicly available, multi-ethnic databases in the US.HCUP is a family of healthcare databases, related software tools, and products developed through a Federal-State-Industry partnership and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.The NIS enables medical researchers to analyze data on more than seven million hospital stays each year in the US.It approximates a 20-percent stratified sample of all discharges from US community hospitals, excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals.The NIS database is publicly available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/.

Study population and outcome measures

We utilized the NIS to identify all adult (≥ 18 years old) LT hospitalizations with AP in the US from 2007–2019.National trends of hospitalization characteristics, clinical outcomes, complications, and the healthcare burden were highlighted.Furthermore, non-LT AP hospitalizations served as controls for a comparative analysis of hospitalization characteristics, clinical outcomes, complications, and the healthcare burden with the LT cohort.Predictors of inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP were also identified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, United States) to account for weights in the stratified survey design of the NIS.During the statistical estimating process, weights were considered by incorporating the variables for strata, weight to discharges and cluster.Descriptive statistics including mean (± standard error) for continuous variables, and count (%) for categorical variables were provided after statistical analysis.The Cochran-Armitage trend tests were implemented to test the trends for proportions of binary variables.The trends for the averages of age, mean length of stay (LOS) and mean total healthcare charge (THC) were examined by using linear regression.The Rao-Scott design-adjusted chi-square test examined the association between binary variables in LT and non-LT hospitalizations with AP.F-statistics from the weighted regression model was used to test the differences in age, mean LOS, and mean THC in LT and non-LT hospitalizations with AP.Adjusted hazard ratios with 95% confidence interval were obtained through Cox proportional hazards regression to identify factors that influenced mortality.All analytical results were considered statistically significant whenPvalues were less than or equal to 0.05.

Ethical considerations

RESULTS

Trends of hospitalization characteristics for LT hospitalizations with AP

There was an increase in the total number of LT hospitalizations with AP from 305 in 2007 to 610 in 2019.We did not find a statistically significant trend for gender or mean age; however, there was an increasing trend of LT hospitalizations with AP for patients aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1).Furthermore, LT hospitalizations with AP had an increasing comorbidity burden as the Charlson Comorbidity Index(CCI) score ≥ 3 increased from 41.64% in 2007 to 62.30% in 2019 (P-trend < 0.0001).Interestingly, we also noted a rising trend of LT hospitalizations with AP from 58.89% in 2007 to 82.79% in 2019 at urban teaching hospitals.

Table 1 Trends of hospitalization characteristics for liver transplant hospitalizations with acute pancreatitis in the United States from 2007–2019, n (%)

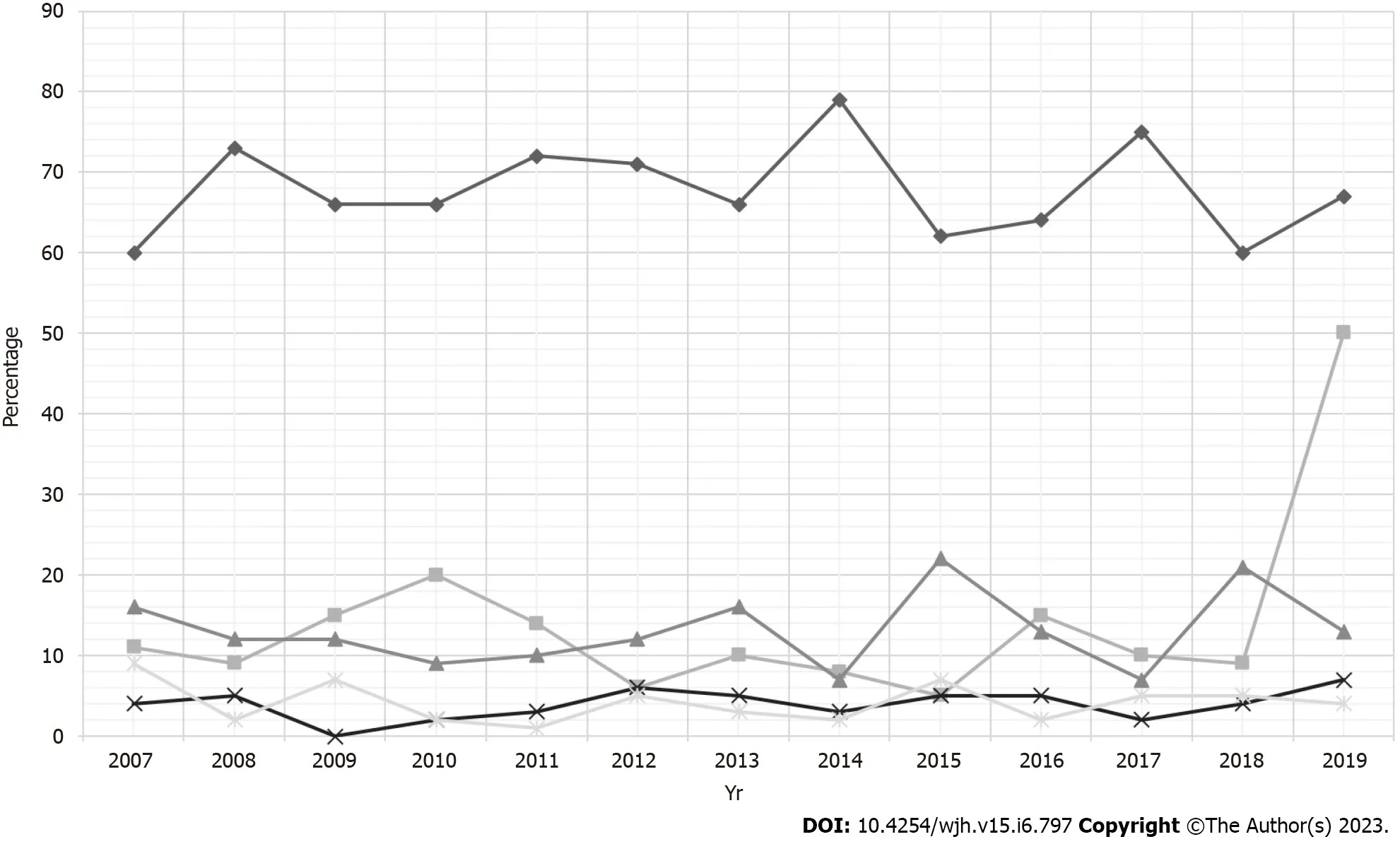

Racial differences in the trends of LT hospitalizations with AP were apparent.Whites made up a majority of the study cohort (Table 1) without a statistically significant trend.We noted an overall increasing trend of Hispanic (16.49% in 2007 to 21.09% in 2018, P-trend = 0.0009) and Asian (4.27% in 2007 to 7.44% in 2019, P-trend = 0.0009) LT hospitalizations with AP (Table 1 and Figure 1).However,Black LT hospitalizations with AP had a declining trend from 11% to 8.26%, P-trend = 0.0004) (Table 1).

Figure 1 Racial trends for liver transplant hospitalizations with acute pancreatitis in the United States from 2007–2019.

Trends of clinical outcomes, healthcare burden and complications for LT hospitalizations with AP

We did not find a statistically significant trend for inpatient mortality, mean LOS, and mean THC for LT hospitalizations with AP (Table 2).However, we observed a rising trend of complications such as sepsis(1.25% in 2007 to 18.03% in 2019, P-trend < 0.0001), acute kidney failure (AKF) (17.13% to 34.43%, Ptrend < 0.0001), acute respiratory failure (ARF) (1.44% to 6.56%, P-trend = 0.0002), abdominal abscesses(0% in 2007 to 0.82% in 2019, P-trend = 0.0006), portal vein thrombosis (PVT) (0% to 4.10%, P-trend <0.0001) and venous thromboembolism (VTE) (1.82% to 7.38%, P-trend < 0.0001) for LT hospitalizations with AP.Moreover, there was a decline in the need for blood transfusion from 6.09% in 2007 to 0% in 2019 (P-trend < 0.0001) for LT hospitalizations with AP.

Table 2 Trends of outcomes for liver transplant hospitalizations with acute pancreatitis in the United States from 2007–2019, n (%)

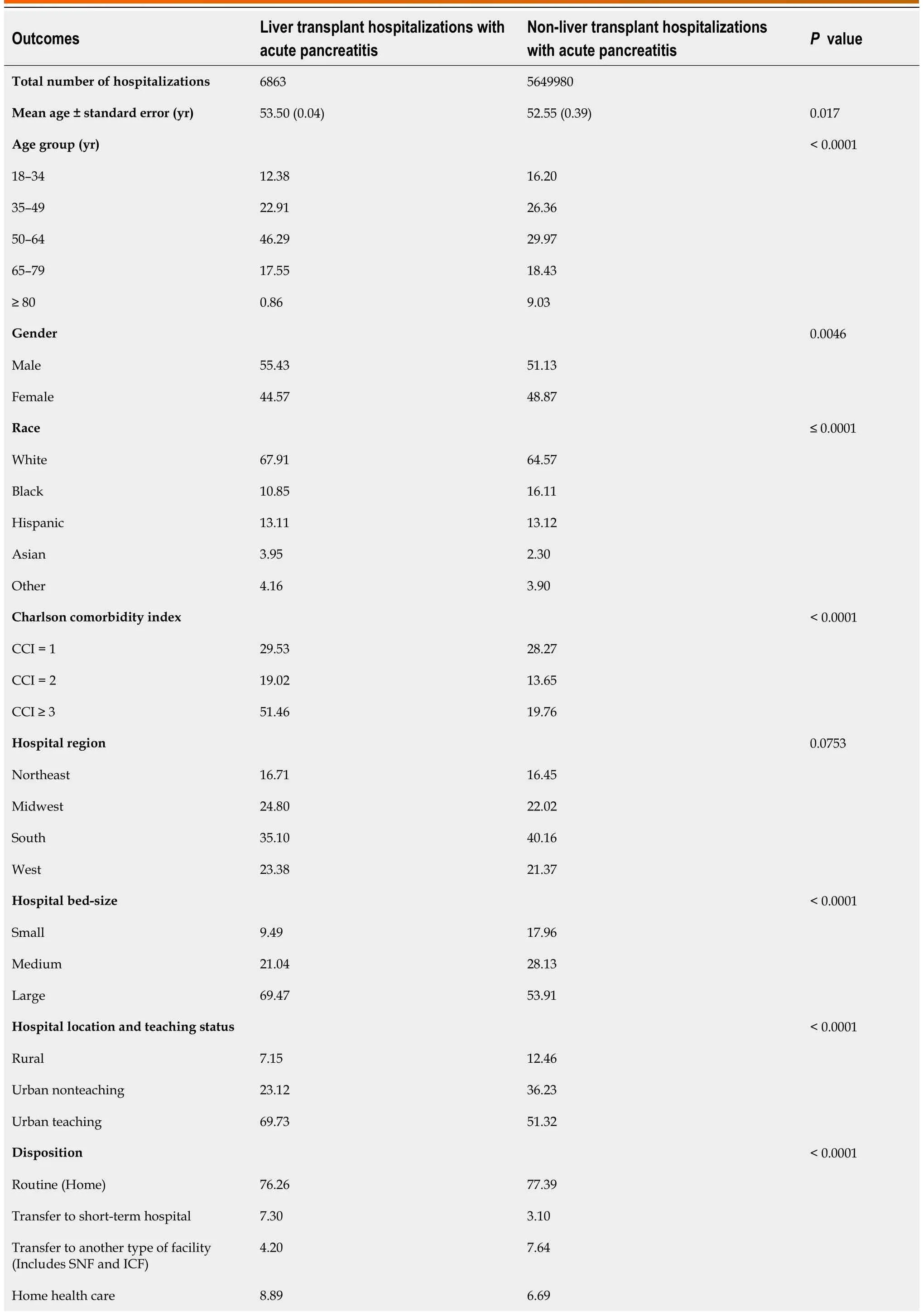

Comparative analysis of hospitalization characteristics for LT and non-LT hospitalizations with AP

Between 2007–2019, there were 6863 LT hospitalizations with AP which were compared to 5649980 non-LT AP hospitalizations.LT hospitalizations with AP had a slightly higher mean age (53.5vs52.55 years,P= 0.017) compared to the non-LT cohort.Furthermore, LT hospitalizations with AP also had a higher proportion of males (55.43%vs51.13%,P= 0.0046) and patients with a CCI score ≥ 3 (51.46%vs19.76%,P< 0.0001) compared to non-LT hospitalizations (Table 3).A majority of LT hospitalizations with AP were at large (69.47%), urban teaching (69.73%) hospitals.

Table 3 Comparative analysis of hospitalization characteristics for liver and non-liver transplant hospitalizations with acute pancreatitis in the United States from 2007–2019, n (%)

Racial differences were observed between the LT and non-LT cohorts.We noted a higher proportion of Whites (67.91%vs64.57%,P< 0.0001) and Asians (3.95%vs2.3%,P< 0.0001) in the LT cohort, while there was a higher proportion of Blacks and Hispanics in the non-LT cohort (Table 3).

Comparative analysis of clinical outcomes, healthcare burden and complications for LT and non-LT hospitalizations with AP

Overall, the inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP was lower (1.37% vs 2.16%, P = 0.0479)than the non-LT cohort (Table 4).We did not find a statistical difference in the inpatient mortality rates after stratifying for age, gender, or race.Although the mean LOS was comparable between both groups,the mean THC was higher for LT hospitalizations with AP ($59596 vs $50466, P-trend = 0.0429)compared to the non-LT cohort.Furthermore, LT hospitalizations with AP also had a higher proportion of patients with complications such as AKF (29.41% vs 14.91%, P < 0.0001), need for blood transfusion(7.65% vs 4.75%, P < 0.0001), PVT (1.53% vs 0.64%, P < 0.0001) and VTE (3.5% vs 2.19%, P = 0.0011)compared to non-LT hospitalizations; however, the non-LT cohort had a higher proportion of patients with pancreatic pseudocysts (5.46% vs 3.85%, P = 0.0259) (Table 4).

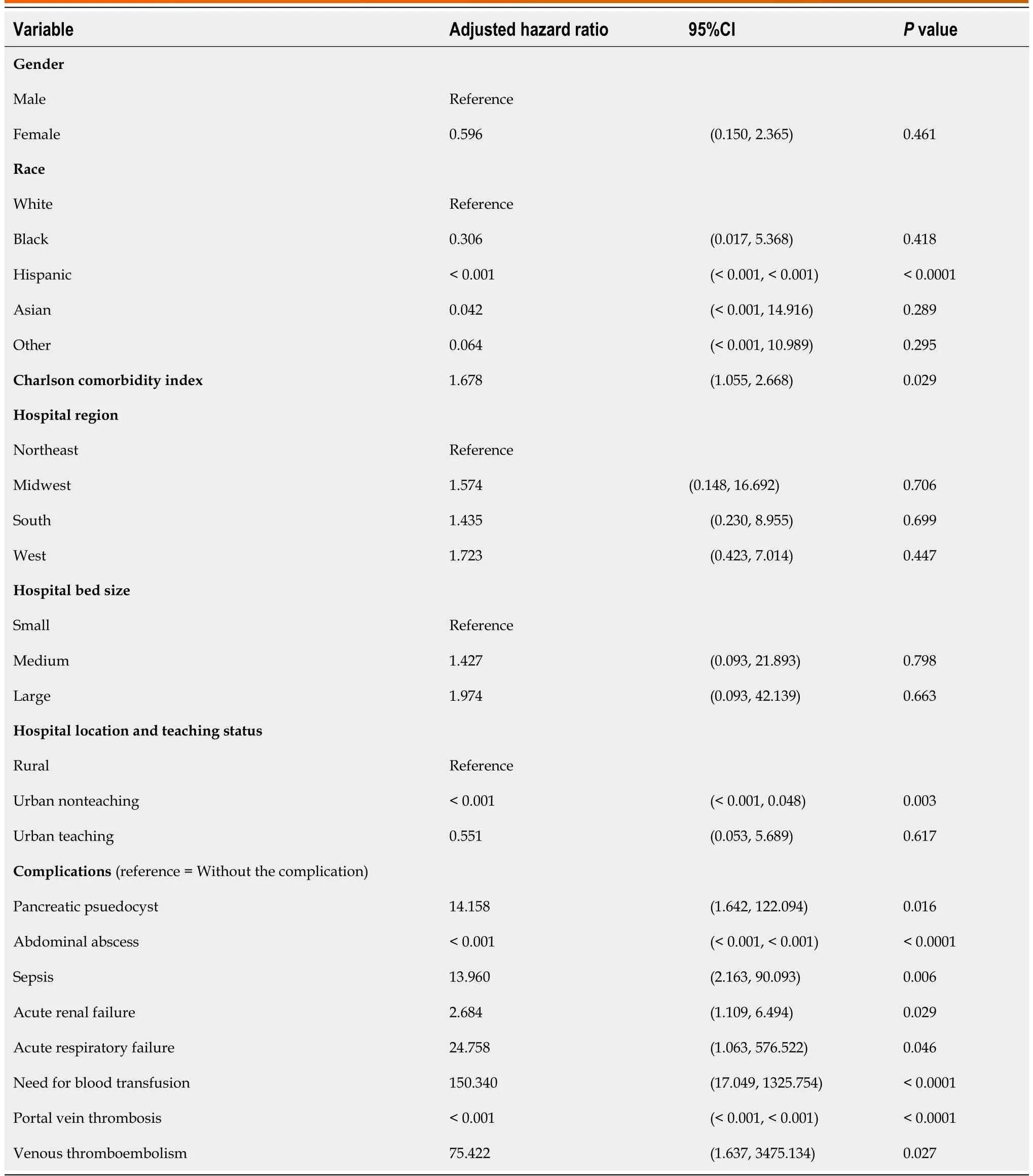

Predictors for inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP

After a regression analysis, Hispanics were noted to have lower odds of inpatient mortality compared to Whites (Table 5).Furthermore, after adjusting for all other variables, every one-point increase in the CCI score was associated with a 67.8% increase in inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP(Table 5).The presence of complications such as pancreatic pseudocysts (aHR: 14.158, 95%CI 1.642-122.094,P= 0.016), sepsis (aHR: 13.960, 95%CI 2.163-90.093,P< 0.0001), AKF (aHR: 2.684, 95%CI 1.109-6.494,P= 0.029), ARF (aHR: 24.758, 95%CI 1.063-576.522,P= 0.046), need for blood transfusion (aHR:150.340, 95%CI 17.049-1325.754,P< 0.0001) and VTE (aHR: 75.422, 95%CI 1.637-3475.134,P= 0.027)were also associated with higher odds inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP after adjusting for all other variables.

高阶累积量是指三阶或三阶以上的随机变量的统计量[2]。用概率和统计的观点来分析,如果事物服从正态随机分布,那么使用一阶、二级统计量就可以描述事物的特征。但是,若分析信号没有遵循正态分布,那低于三阶统计量就无法表示事物的变化规律,而三阶或三阶以上的统计量可以表现信号的特征。

Table 5 Predictors of inpatient mortality for liver transplant hospitalizations with acute pancreatitis in the United States from 2007–2019

DISCUSSION

AP is a well-known clinical entity.Although it has been thoroughly studied in the general population,there is a significant paucity of data on AP in solid-organ transplant recipients, particularly those undergoing LT.This is the only study in current literature that investigates trends, clinical outcomes,and the healthcare burden of LT hospitalizations with AP at a national level.In this study, we noted an increase in LT hospitalizations with AP with a rising trend for ethnic minoritiesi.e.Hispanics and Asians; however, we did not find a statistically significant trend of inpatient mortality, mean LOS and mean THC.Although the LT cohort was slightly older and had a higher comorbidity burden, the overall inpatient mortality was lower (1.37%vs2.16%,P= 0.0479) compared to the non-LT cohort.Furthermore,LT hospitalizations with AP had a higher proportion of patients with AKF, PVT, VTE, and the need for blood transfusion compared to the non-LT cohort.Increasing CCI and the presence of pancreatic pseudocysts, sepsis, ARF, AKF, VTE, and the need for blood transfusion were associated with increased odds of inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP.With the increasing rates of liver transplants being performed and relative organ shortage in the US, it is vital to understand patient characteristics, outcomes, and complications of LT hospitalizations with AP to potentially reduce adverse clinical outcomes in these high-risk individuals[18].

As per data available from United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the total number of LT increased from 6494 in 2007 to 8896 in 2019[18].However, in our study, the total number of LT hospitalizations with AP increased disproportionally, essentially doubling in the same time frame.In the US, the rates of LT for patients ≥ 65 years of age have also been on the rise as there is a general consensus that LT in the elderly is feasible with acceptable short-term and long-term results[28,29].Similarly, in this study, we noted an increase in the rates of LT hospitalizations with AP for patients > 65 years of age(Table 1).However, it should be noted that AP carries a higher morbidity and mortality burden in the elderly population at baseline, and this is compounded in organ transplant recipients[30].

In the US, there was an increase in LT for Hispanics and Asians from 912 in 2007 to 1498 in 2019 and 325 in 2007 to 363 in 2019, respectively as per the UNOS registry.Current literature lacks data on the racial distribution of AP in LT recipients, particularly for ethnic minoritiesi.e.Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians.However, studies have demonstrated that ethnic minorities, at baseline, are at a higher risk of developing AP and have greater severity of disease compared to the general population[2,31-35].In our study, there was an increasing trend of Hispanic and Asian LT hospitalizations with AP (Figure 1)which was disproportionate to the increase in LT for this population.Interestingly, Black LT hospitalizations with AP were noted to have a declining trend between 2007–2019.After a comparative analysis,we observed a higher proportion of Asians in the LT cohort, while there was a higher proportion of Blacks and Hispanics in the non-LT cohort.The exact reason for this variable racial distribution is currently unknown but needs further investigation through large, multi-center prospective studies.Furthermore, we emphasize the need for early recognition and prompt treatment of AP in Hispanic and Asian LT hospitalizations to prevent adverse clinical outcomes.

Statistics have demonstrated continuous improvements in survival rates for liver transplant recipients[36-38].Over the last few decades, AP-related mortality has also declined due to prompt recognition and improvement in management strategies[1,39].However, prior literature offers conflicting evidence on ethnic variations in AP-related mortality with some studies reporting increased mortality rates in Whites, while others noted higher mortality rates in Blacks among the general population[14,40].There continues to be a significant paucity of data on mortality for AP in LT recipients in current literature.In our study, we did not find a statistically significant trend for inpatient mortality in LT hospitalizations with AP (Table 2).Interestingly, after a comparative analysis, LT hospitalizations with AP had lower inpatient mortality rates compared to the non-LT cohort despite a higher mean age, greater comorbidity burden, and higher proportion of patients with complications.Furthermore, we did not find a statistical difference in the inpatient mortality rates after stratifying for age, gender, or race.The exact reason for lower inpatient mortality rates in LT hospitalizations with AP is unknown.However, it may, in part, be due to increased vigilance for complications in these high-risk hospitalizations, overall improvements in management strategies, and a multi-disciplinary team approach for management of these highly complex patients.Additional multi-center prospective studies are needed to further investigate these findings.Nonetheless, lower mortality suggests improved survival rates for LT hospitalizations which is in line with current literature.

Healthcare utilization by LT recipients is on the rise.A study by Habkaet al[41] in 2015 predicted that the cost of LT will increase by 33% in 10 years and 81% in the next 20 years.The inpatient cost of management of AP has also almost doubled from 1996 ($3.9 billion) to 2016 ($7.7 billion)[42].On the contrary, the utilization of the inpatient service (bed days per prevent case) for AP has declined over the years[42].No data currently exists on healthcare utilization for AP in LT recipients.In our study, we did not find a statistically significant trend in mean LOS and mean THC for LT hospitalizations with AP indicating that the healthcare burden has remained relatively stable over the years despite a higher proportion of patients with complications such as sepsis, AKF, ARF, PVT, VTE, and abdominal abscesses.After a comparative analysis, the mean LOS was comparable between the LT and non-LT cohorts; however, the mean THC for the LT cohort was $9130 higher than that of the non-LT cohort.This may, in part, be attributed to a higher proportion of patients with complications in the LT cohort compared to the non-LT cohort requiring a higher level of care and multi-disciplinary team management (Table 4).Furthermore, after adjusting for all other variables, increasing CCI, and the presence of complications such as pancreatic pseudocysts, sepsis, ARF, AKF, VTE, and need for blood transfusions were associated with higher odds of inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP.These findings somewhat mirror predictors of inpatient mortality for AP that have been reported in previous population-based studies[43].

Our study has several strengths and a few limitations.Our study population, which was drawn from one of the largest, publicly available, multi-ethnic databases in the US, is a key strength of this study.This is the only study in the current literature that offers a national perspective on hospitalization characteristics, clinical outcomes, complications, and the healthcare burden of LT hospitalizations with AP over 13 years, compared to other single-center experiences which offer limited information.Through a comprehensive and unique analysis technique, we were also able to compare LT and non-LT hospitalizations to understand the influence of AP on LT hospitalizations thereby giving gastroenterologists real world data.Furthermore, as the NIS covers approximately 97% of the US population, the results of our study are applicable to all LT hospitalizations with AP in the US.

However, we do acknowledge the limitations associated with our study.The retrospective study design makes our study susceptible to the biases that are associated with retrospective studies.Additionally, the NIS database does not contain information on the indication of liver transplant, time from LT to development of AP, disease severity, hospital course, treatment aspects of the disease, time from any procedure to development of complications, procedural complications (pre, intra, and post),intraprocedural operator preferences, or performance of any procedure.Lastly, the NIS is an administrative database that uses ICD codes to store data; hence, the possibility of human coding errors always exists.Despite these limitations, our large sample size, unique analysis technique, and multi-faceted outcomes add valuable data to limited literature.

CONCLUSION

LT is a lifesaving procedure for chronic end-stage liver disease patients.However, the development of post-LT pancreatitis may lead to poor surgical outcomes and development of complications.In our study, we noted an increase in LT hospitalizations with AP, particularly for ethnic minoritiesi.e.Hispanics and Asians; however, there was no trend for inpatient mortality.We also did not find a statistically significant trend mean LOS and mean THC indicating that healthcare utilization has remained relatively stable for LT hospitalizations with AP between 2007–2019.On comparison, LT hospitalizations with AP had lower inpatient mortality compared to non-LT AP hospitalizations despite a higher proportion of patients that were older, had CCI ≥ 3, and had complications such as AKF, PVT,VTE, and need for blood transfusion.Increasing CCI, presence of pancreatic pseudocysts, sepsis, ARF,ARF, VTE, and need for blood transfusion were identified to be independent predictors of inpatient mortality for LT hospitalizations with AP.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Dahiya DS, Jahagirdar V, Chandan S, Inamdar S, Sharma N, and Al-Haddad M contributed to conception and design; Dahiya DS, Cheng CI, and Al-Haddad M contributed to administrative support; Dahiya DS and Cheng CI contributed to provision, collection, and assembly of data; all Authors contributed to review of literature, drafting the manuscript, revision of key components of the manuscript, final approval of manuscript,agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Institutional review board statement:The NIS database lacks patient and hospital-specific identifiers to protect patient privacy and maintain anonymity.Hence, our study was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval as

per guidelines put forth by our IRB for analysis of database studies.

Informed consent statement:The data for this study was collected from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS)database.As the NIS database lacks patient-specific and hospital-specific identifiers, this study did not require informed consent.The NIS database is available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement:The NIS database is publicly available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORCID number:Dushyant Singh Dahiya 0000-0002-8544-9039; Vinay Jahagirdar 0000-0001-6685-1033; Saurabh Chandan 0000-0002-2661-6693; Manesh Kumar Gangwani 0000-0002-3931-6163; Hassam Ali 0000-0001-5546-9197; Daryl Ramai 0000-0002-2460-7806; Chin-I Cheng 0000-0002-0273-8135; Sumant Inamdar 0000-0002-1002-2823; Neil R Sharma 0000-0001-8567-5450; Mohammad Al-Haddad 0000-0003-1641-9976.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Liu JH

World Journal of Hepatology2023年6期

World Journal of Hepatology2023年6期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Management of sepsis in a cirrhotic patient admitted to the intensive care unit: A systematic literature review

- Liver injury from direct oral anticoagulants

- Randomized intervention and outpatient follow-up lowers 30-d readmissions for patients with hepatic encephalopathy, decompensated cirrhosis

- Lower alanine aminotransferase levels are associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver patients

- Role of vascular endothelial growth factor B in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its potential value

- Tumor budding as a potential prognostic marker in determining the behavior of primary liver cancers