The Blue Lotus and Beyond:A Cross-Cultural Dialogue between Hergé and Zhang Chongren*#

PAN Zhiyuan

Abstract: The Blue Lotus,an episode set in Shanghai of the popular Belgian comic,The Adventures of Tintin,was the result of a collaboration in 1934-35 between Hergé,its creator,and Zhang Chongren,a Shanghai-born art student in Brussels.This paper demonstrates that the key legacy of the comic is its message calling for mutual understanding between different cultures.Despite the considerable amount of literature on The Blue Lotus thanks to the popularity of Tintin,the existing research tends to either mystify or simplify the Hergé-Zhang encounter and its attendant influences.Taking a more contextualized approach to engage the immediate historical and literary background of the comic,this paper focuses on how a cross-cultural dialogue between Hergé and Zhang contributed to the two significant features in The Blue Lotus: raising a voice against injustice in the contemporary Sino-Japanese conflict,and breaking the established framework of cultural stereotypes.It shows that the collaborators’ in-depth conversation about different cultures and civilizations functioned not only to provide new knowledge,but also to facilitate an understanding from others’ perspectives,with a further analysis of the comic itself to verify this impact.Created on the foundation of a cross-cultural dialogue,this comic in turn became a medium to promote the idea of cultural respect and tolerance to readers of Tintin,which is still relevant today.

Keywords: The Blue Lotus; Hergé; Zhang Chongren; Sino-Japanese conflict;cultural stereotype; cross-cultural dialogue

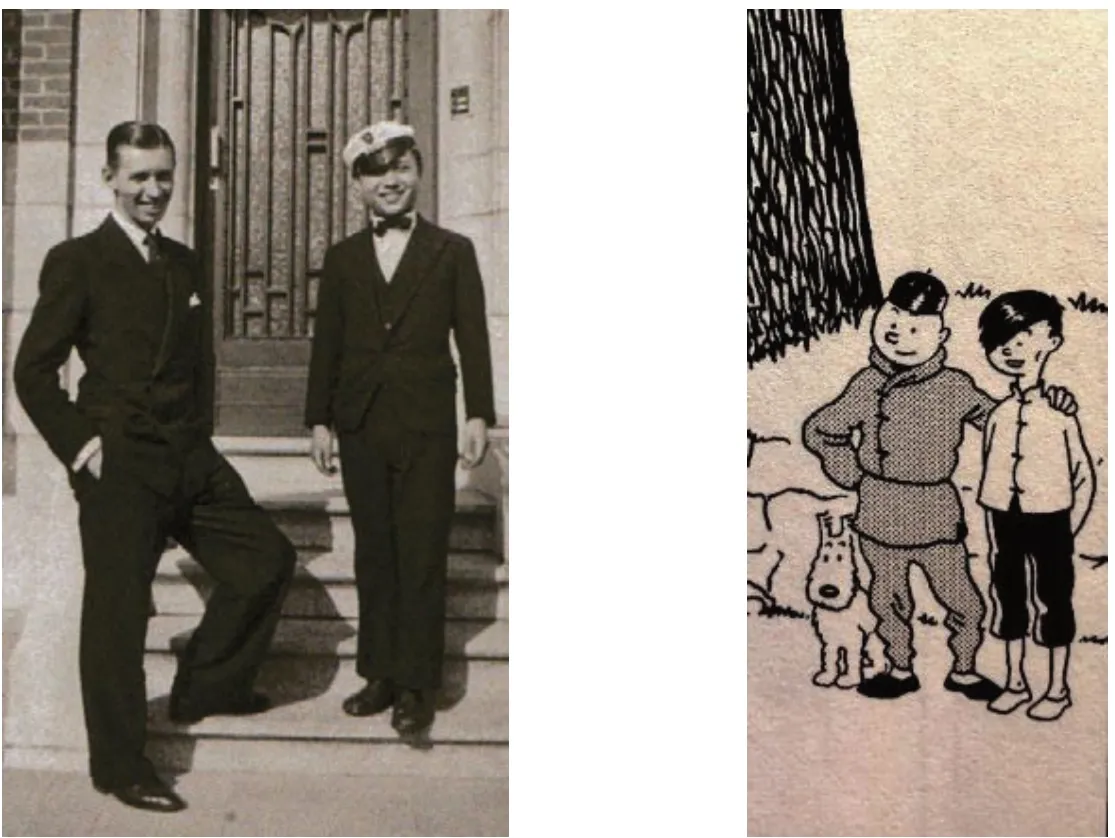

On March 18,1981,at Brussels Zaventem Airport,a crowd of journalists and fans were waiting to witness a reunion between a Belgian and a Chinese.This Belgian was Hergé,the creator ofTheAdventuresofTintin(Les Aventures de Tintin); this Chinese was Zhang Chongren张充仁 (1907-1998),a friend of his as well as the co-creator of theTheBlueLotus(Le Lotus bleu),an episode of the comic strip (bandedessineéin francophone contexts,1Bande dessineé (abbreviated as BD), literally “drawn strips,” refers to Franco-Belgian comics.It emerged in the 1920s.Before the Second World War, BDs were almost exclusively published as tabloid size newspapers intended for children or youth readers.Developed after the War, weekly BD magazines and albums gained popularity.A hardback A4 size album is the main format and remains popular among audience in Belgium and France today.It is regarded as “the ninth art” (le neuvième art) in francophone culture.The term bande dessineé was first introduced in the 1930s and has become a popular genre of comics since the 1960s, alongside Japanese manga, American graphic novels and Anglophone cartoons.Representative BDs are The Adventures of Tintin (Hergé), Gaston Lagaffe (Franquin), Asterix (Goscinny & Uderzo), Lucky Luke (Morris & Goscinny), and The Smurfs (Peyo).hereafter comic)set in China.They were both in their seventies.It had been forty-seven years since they had last met (fig.1).Due to the popularity ofTintin,this event drew great attention from the public.2“La Vidéo des Retrovailles entre Hergé et Tchang (The Video of the Reunion of Hergé and Zhang) (1981),” Tintinomania(blog), January 2, 2019, https://tintinomania.com/tintin-retrouvailles-tchang.

Figure 1 Reunion of Zhang and Hergé at the Brussels Airport in 1981, with Zhang Xueren (son of Zhang) on the right.Image from “Zhang Chongren Chuanqi Yisheng.”

Tintinbegan to be serialized inLePetitVingtième(The Little Twentieth) in 1929,the youth weekly supplement of the Belgian newspaperLeVingtièmeSiècle(The Twentieth Century).Each story in this series unfolds how the journalist protagonist Tintin restores justice and helps the weak around the world.In the years to come,Tintinbecame more and more popular: “from the point of view of sales (more than 120 million books sold in almost 40 languages),durability (60 years old in 1989),range of appeal (from small children to pensioners) or critical interest (more books have been written aboutTintinand his creator than on strip cartoons in general).”3Benoît Peeters, Tintin and the World of Hergé (London: Methuen, 1989), 151.

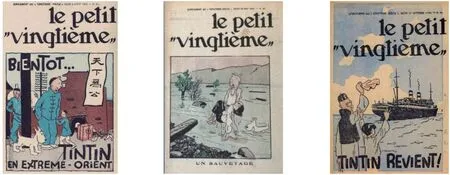

Back in 1934 Brussels,following adventures in the Soviet Union,the Congo,America and the Middle East,Tintin embarked on a new destination,Shanghai.The comic would run from August 1934 to October 1935.It was the fifth episode in the series,and was originally called“Tintin in the Far East” (Tintin en extrême-orient) before being renamed “The Blue Lotus” in 1936.4For convenience and coherence, the paper will use “The Blue Lotus” to refer to the comic throughout, though during 1934-1936 this title was not yet in use.Unlike other Tintin stories,TheBlueLotuswas a product of close collaboration.

Hergé (pseudonym of Georges Prosper Remi,1907-1983) met up with Zhang (1907-1998),who was an art student of oil painting and sculpture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts(Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts),for the first time on May 1,1934.Zhang recorded in his diary: “Visited Hergé.He draws weekly illustrations forVingtièmeSiècle.In need of materials of China,he requested my help.”5Jean-Michel Coblence and Tchang Yifei, Tchang, Comment l’amitié déplaça les montagnes (Chang, How Friendship Moved the Mountains) (Moulinsart, 2003), 52.Coming from Shanghai,Zhang gave Hergé a detailed introduction to contemporary China,which was absorbed into the context ofTheBlueLotus.As recalled by Zhang,the procedure was that Hergé would develop the thread,work out a draft and give it to him to revise (including the street scenes,customs and Sino-Japanese relationship where involved).6张充仁:《自述传记》(节选),见张充仁纪念馆、上海张充仁艺术研究交流中心:《张充仁艺术研究系列3:文论》,上海:上海人民美术出版社,2010年,第202页。[ ZHANG Chongren, “Zishu Zhuanji(Jiexuan)” (Autobiography [Selected]), in Wenlun (Zhang Chongren Yishu Yanjiu Xilie 3) (Selected Essays on Zhang Chongren), ed.Zhang Chongren Jinianguan,Shanghai Zhang Chongren Yishu Yanjiu Jiaoliu Zhongxin (Zhang Chongren Museum and Shanghai Research and Communication Centre of the Arts of Zhang Chongren), Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2010, 202.]Hergé also testified that all the Chinese characters inTheBlueLotuswere written by Zhang or modelled according to his writing.7Hergé and Numa Sadoul, Tintin et moi: entretiens avec Hergé (Tintin and Me: interviews with Hergé), Champs 529 (Paris:Flammarion, 2003), 131.Michael Farr commented that: “The result is a masterpiece.Tintin is immersed in extreme realism—Shanghai exactly as it was in 1934.It takesTintinto a level we had not seen before,because the previous adventures were approximations of a country [...] They did not have the rich,accurate detail ofTheBlueLotus.”8Michael Farr,“The Best Book on Tintin,” n.d., https://fivebooks.com/best-books/tintin-michael-farr/.

From this collaboration,Zhang and Hergé became close friends.Inspired by Zhang,Hergé found Tintin a Chinese friend during his adventure in Shanghai,“Tchang.” The Tintin-Tchang friendship mirrored the real friendship of their creators (fig.2).According to Zhang’s recollection,Hergé had wanted to give him credit as co-author but he did not accept.9Pierre Assouline, Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 52.Nevertheless,Zhang’s name partially appears on a shop sign in a drawing (fig.3).

Figure 2 left, Zhang and Hergé in Brussels; right, Tintin and Tchang in The Blue Lotus.Images from Tchang, Comment l’amitié déplaça les montagnes and Le Lotus bleu

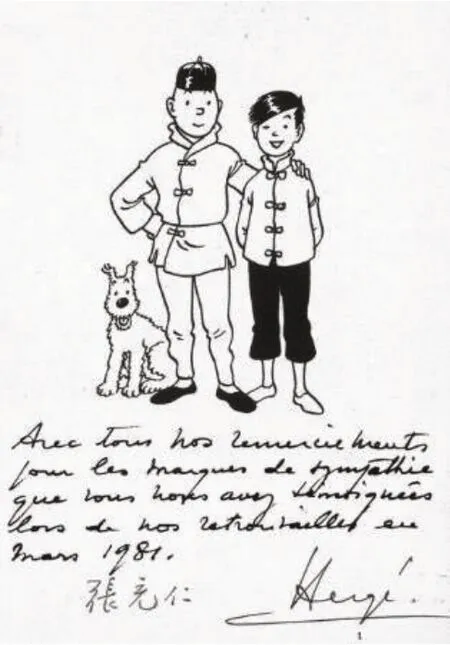

During the reunion event in 1981,they co-signed and gave a printed card to attendees,on which Tintin,dressed in Chinese attire,puts one arm round Tchang’s shoulder,reproducing the scene inTheBlueLotuswhen they took a picture together.The inscription reads: “With all our gratitude for the expressions of friendliness that you have shown us during our reunion in March 1981” (fig.4).Their collaboration is well-known and widely recognized,being highlighted at both of their retrospective exhibitions held in Belgium and China during recent years.10“Zhang Chongren and Belgium,” China Cultural Center in Brussels, https://www.cccbrussels.be/news/exhibitions/zhangchongren-and-belgium.html, [ November 8, 2022 ]; “Tintin and Hergé,” Power Station of Art,https://www.powerstationofart.com/whats-on/exhibitions/ding-ding-and-herge, [ November 8, 2022 ].To some extents,this story of friendship epitomized the amicable side of the relationship between the two countries.

Figure 4 Printed card co-signed by Zhang and Hergé.Image from the preview of the auction on November 22, 2014, by Artcurial.

In fact,what makes the encounter between Hergé and Zhang remarkable is not merely a firm friendship withstanding time and space.As articulated by Hergé during the interview at the reunion: “How can I explain such an emotion? How can one describe the feelings one has when one meets,after nearly half a century,someone who was more than a friend,someone who,as I said earlier,opened doors and windows for me on a whole civilization I knew almost nothing about? It was a world Zhang opened up to me.”11Moi, Tintin (Me, Tintin), 1992, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXHsK0cUqoI.It indicates that their meeting was beyond a technical collaboration,and led to a profound dialogue about different cultures and civilizations.In his letter to Zhang in 1975,Hergé also wrote that: “thanks to you,finally I discovered—after Marco Polo—China,its civilisation,its thinking,its art and artists.”12Hergé to Zhang Chongren, May 1, 1975.

This significance has not gone unnoticed by researchers ofTintin,but has not been fully explored either.This paper will first give a brief review of the existing scholarship before focusing on two aspects inTheBlueLotus,which have long-term impacts in various domains: the presentation of the Sino-Japanese conflict in the 1930s,and the change of view in cultural perception.It will put the comic in its immediate historical,social and literary contexts,so as to elaborate how a cross-cultural dialogue functioned.Finally,engaging with reviews from readers,it aims to show that the key legacy ofTheBlueLotusis to facilitate mutual understanding,and in turn to inspire the wider public to reflect beyond one’s own national and cultural boundaries.

I.Existing Research on The Blue Lotus

Given the popularity ofTintin,many researchers (i.e.“Tintinologists”) have written about Hergé andTintin,particularly in French.13Research engages various angles, for example: Hergé and Michel Daubert, Tintin: The Art of Hergé, trans.Michael Farr(New York, N.Y.: Abrams ComicArts, 2013); Francis Bergeron, Hergé, le voyageur immobile: Géopolitique et voyages de Tintin,de son père Hergé et de son confesseur l’abbé Wallez (Hergé, the Motionless Traveler: Geopolitics and Travels of Tintin, His Father Hergé and His Confessor, Father Wallez) (La Chaussée d’Ivry: Atelier Fol’fer, 2015); Philippe Goddin, Hergé and Tintin,Reporters: From Le Petit Vingtième to Tintin Magazine (London: Sundancer, 1987); Marcel Wilmet, Tintin noir sur blanc: l’aventure des aventures, 1930-1942 (Tintin Black on White: The Adventure of the Adventures), 1 vol.(Brussels: Casterman, 2011).Currently there are two trends in the study ofTheBlue Lotus.One is the tendency to mystify it,which falls into the group of books that “read” the hidden messages ofTintin.14Jean-Marie Apostolidès, The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults, trans.Jocelyn Hoy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010); Jan Baetens, Hergé écrivain (Hergé, Writer), Champs (Paris: Flammarion, 2010); Tom McCarthy, Tintin and the Secret of Literature (London: Granta, 2007).One of the reasons for this is the limited access to first-hand information about Hergé,due to the control of the Hergé Foundation which owns most of his archives and has commercial considerations ofTintin.15Thompson, Tintin, Author’s Note.It resulted in the phenomenon that a large number of publications are exegetical analyses which attempt to “reveal” the “hidden messages”between lines(or images).16Baetens,Hergé écrivain (Hergé, Writer); McCarthy,Tintin and the Secret of Literature; Dominique Cerbelaud, “Le héros christique” (The Christic Hero), in L’archipel Tintin, Réflexions faites (Brussels: les Impressions nouvelles, 2012), 36-49;Olivier Reibel,La vie secrète d’Hergé: biographie inattendue (Hergé’s Secret Life: An Unexpected Biography), 1 vol.(Paris:Dervy, 2010).TheBlueLotusreceived special attention because of its unfamiliar setting and Chinese words appearing in the drawings,which make it mysterious for a Western reader.17Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle, Les mystères du Lotus Bleu (The Mysteries of The Blue Lotus) (Brussels: Éditions Moulinsart,2006); Patrick Merand and Li Xiaohan, Lotus Bleu décrypté (Blue Lotus Decrypted) (Saint-Maur-des-Fossés: Sépia BD, 2009).Interpretative reading is thus popular: Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle focused on visual analysis of the black & white version,and argued that the use of light effects symbolized the contrast;18Fresnault-Deruelle, Les mystères du Lotus Bleu (The Mysteries of the Blue Lotus).Jean-Marie Apostolidès discussed the plot and claimed that the poisoned character Didi always trying to behead his father and mother should be understood as an expression of the Oedipus complex.19Apostolidès, The Metamorphoses of Tintin; Baetens, Hergé écrivain (Hergé, Writer); McCarthy, Tintin and the Secret of Literature.

The enduring Hergé-Zhang friendship also baffled many Western Tintinologists.Harry Thompson questioned: “for a relationship based on one year’s relationship half a century before,theirs had a lot to live up to.”20Thompson, Tintin, 198.The British translator ofTintin,Michael Turner,once commented: “for Hergé,the relationship with Chang [Zhang] had become a mystical relationship.”21Thompson, 198.It gave rise to some,as far as I am concerned,ungrounded speculations: the French investigative journalist Roger Faligot tried to insert a left-wing political conspiracy behind the scene;22Roger Faligot and Jean-Luc,“Tchang: un espion chinois? L’énigme du Lotus bleu” (Zhang: a Chinese spy? The Enigma of The Blue Lotus), Tintinomania (blog), https://tintinomania.com/tintin-tchang-espion-chinois, [January 14, 2018].Laurent Colonnier also conjured up a similar plot.23Laurent Colonnier, Georges & Tchang: Une Histoire d’amour au Vingtième Siècle (Georges & Zhang - A Story of Love in the 20th Century) (Grenoble: Glénat BD, 2012), https://www.tintinologist.org/forums/index.php?action=vthread&forum=11&topic=5133.

The other plainer approach is to narrate the background story ofTheBlueLotusaccording to accessible accounts,usually in a biographical manner.Researchers of Hergé,such as Pierre Assouline,Benoît Peeters and Philippe Goddin,and those of Zhang,including Chen Yaowang and Fu Weixin,have all been well aware of Hergé and Zhang’s meeting,and have discussed the significance.24Pierre Assouline and Charles Ruas, Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009);Benoît Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, trans.Tina A.Kover (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012); Philippe Goddin,Hergé: Lignes de Vie (Brussels: Éditions Moulinsart, n.d.); 陈耀王:《塑人塑己塑春秋:张充仁传》,上海:学林出版社,2013年[ CHEN Yaowang, Suren Suji Suchunqiu: Zhang Chongren Zhuan (Cultivate People, Shape Oneself, Create History:Biography of Zhang Chongren), Shanghai: Xuelin Press, 2013 ]; 陈耀王:《既雕且琢,复归于璞:张充仁的艺术生涯》,香港:基督教中国宗教文化研究社,2016 年[ CHEN Yaowang, Jidiaoqiezhuo Fuguiyupu: Zhang Chongren de Yishu Shengya(Return to Simplicity after Carving and Chiselling: The Art Life of Zhang Chongren), Studies in the History of Christianity in China 6, Hong Kong: Christian Study Centre on Chinese Religion & Culture, 2016 ]; 傅维新:《张充仁传奇一生(上)》,《艺术家》2002 年9 月第328 期,第274~306 页[ FU Weixin, “Zhang Chongren Chuanqi Yisheng” (The Legendary Life of Zhang Chongren [Part One]), Yishujia (Artist) 328 (September 2002): 274-306 ]; 傅维新:《张充仁传奇一生(下)》,《艺术家》2002 年9 月第329 期,第386~414 页[ FU Weixin,“Zhang Chongren Chuanqi Yisheng ” (The Legendary Life of Zhang Chongren [Part Two]), Yishujia (Artist) 329 (September 2002): 386-414; 张充仁纪念馆主编:《张充仁研究》,上海:上海人民美术出版社,2007 年[ ZHANG Chongren Jinianguan (Memorial Hall of Zhang Chongren), ed., Zhang Chongren Yanjiu (Studies on Zhang Chongren), 3 vols., Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2007 ].The common problem is that of brevity,with usually a few sentences describing the encounter.One major reason is that neither side had much knowledge about the other: the researchers studying Hergé did not know about Zhang in detail and vice versa.Another problem is that the studies usually took their words at face value without looking at a bigger picture.

In order to de-mystifyTheBlueLotuson one hand,and to enrich the understanding of this piece of popular literature on the other hand,a more contextualized approach is called for.The current scholarship has already provided a foundation for a further investigation: in addition to biographical information,Michael Farr was the first to discuss the character Tchang together with its model Zhang; Pierre Borvin discussed the important influences on Hergé,including that of Zhang; and Jean-Loup Batelière produced a book to explore how Hergé createdTheBlueLotus,to name but a few.25Michael Farr and Hergé, Tintin & Co.(London: Egmont, 2007); Pierre Borvin, Hergé sous Influence (Saint-Félicien, 2012),102-23; Jean-Loup Batelière, Comment Hergé a Créé Le Lotus bleu (How Hergé Created The Blue Lotus) (Bédéstory, 2009).In this paper,relevant contexts will be drawn into the following discussion of two particular aspects: for theme of the Sino-Japanese Conflict presented in the comic,the geo-political background will be taken into consideration; for the awareness of cultural stereotypes,other cross-cultural practices in a similar vein will be looked at.The inner coherence ofTintinas a whole will be kept in mind as well,serving to better orientTheBlueLotus.

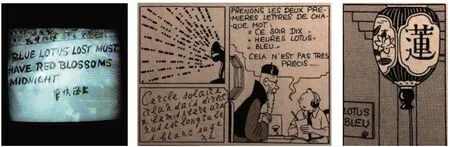

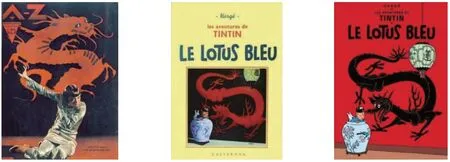

Finally,a note on the version needs to be clarified,asTintinunderwent many revisions from a weekly serialization to a book.In 1936,Hergé wanted to promote the adventure story of China using book format.26Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, 79.To make the title more appealing,he adopted “Blue Lotus,” the name of the opium den in the comic (fig.5.1).He also designed the coloured cover which took inspiration from a photo inA-Zmagazineof Anna May Wong 黃柳霜 (1905-1961),who played a role in the popular filmShanghaiExpress27Shanghai Express is a 1932 American film directed by Josef von Sternberg and starring Marlene Dietrich, Clive Brook,Anna May Wong, and Warner Oland.Set on a three-day express train from Beiping to Shanghai in the civil war-embroiled China, the story is about love and adventure between the British Captain Donald Harvey and “Shanghai Lily” Madeline.It was a financial success with box office of 3.7 million dollars.(fig.5.2).28Wilmet, Tintin noir sur blanc, 62-63; “The Blue Lotus,” http://en.tintin.com/albums/show/id/29/page/0/0/the-blue-lotus,[ July 13, 2019 ].The standard version today came about after 1942,when the publisher Casterman asked Hergé to reformat all his stories into colour and to adopt a strict capacity of 62 pages compared with the 100 to 130 page-length of the black &white books.29Peeters, Tintin and the World of Hergé, 70.TheBlueLotuswas finalized in 1946.This paper will use the black & white book version of 1936,which is closer to the original when it first came out.30Hergé, Le Lotus Bleu (B&W Facsimile Version), Les Aventures de Tintin 5 (Tournai: Casterman, 2010).

Figure 5.1 Left, the mysterious telegram of a “blue lotus” in Shanghai Express; middle and right, the encrypted telegram pointing to the Blue Lotus opium den in The Blue Lotus.Images from the Tintin website and Le Lotus bleu.

Figure 5.2 Left, photo of Anna May Wong in A-Z magazine (1932); middle, cover of The Blue Lotus(1936 edition); right, cover of The Blue Lotus (1946 edition).Images from the Tintin website.

II.Speaking up against Injustice

The story ofTheBlueLotustook place against the backdrop of the Sino-Japanese conflict in the 1930s.Tintin arrived in Shanghai after receiving a message seeking his help.He soon joined forces with the Sons of the Dragon,the local secret society led by Mr.Wang.The society was to combat an opium smuggling group which was operated by the Japanese agent Mitsuhirato平野松成 and held secret meetings at an opium den called “Blue Lotus.” With the help of Tchang,a Chinese orphan boy whom he had saved from a flooding river,Tintin thwarted the traps set for him by bandits,associated with mainly the Japanese.Eventually,Tintin,Tchang and other members of the Sons of the Dragon worked together and arrested the opium traffickers at the“Blue Lotus” opium den.In the end,Tintin tearfully said his goodbyes to Tchang and Mr.Wang at the dock and boarded the boat back to Belgium (fig.6).31Hergé.

Figure 6 Some covers of “Tintin in the Far East”: left, the announcement of the forthcoming comic, with the motto “What is under heaven is for all” of Sun Zhongshan in Chinese on the banner (August 2nd, 1934);middle, “a rescue” as Tintin saves Tchang from the flood (May 30, 1935); right, “Tintin returns!” as Mr.Wang and Tchang wave goodbye to the boat departing from Shanghai (October 17, 1935).Images from the internet.

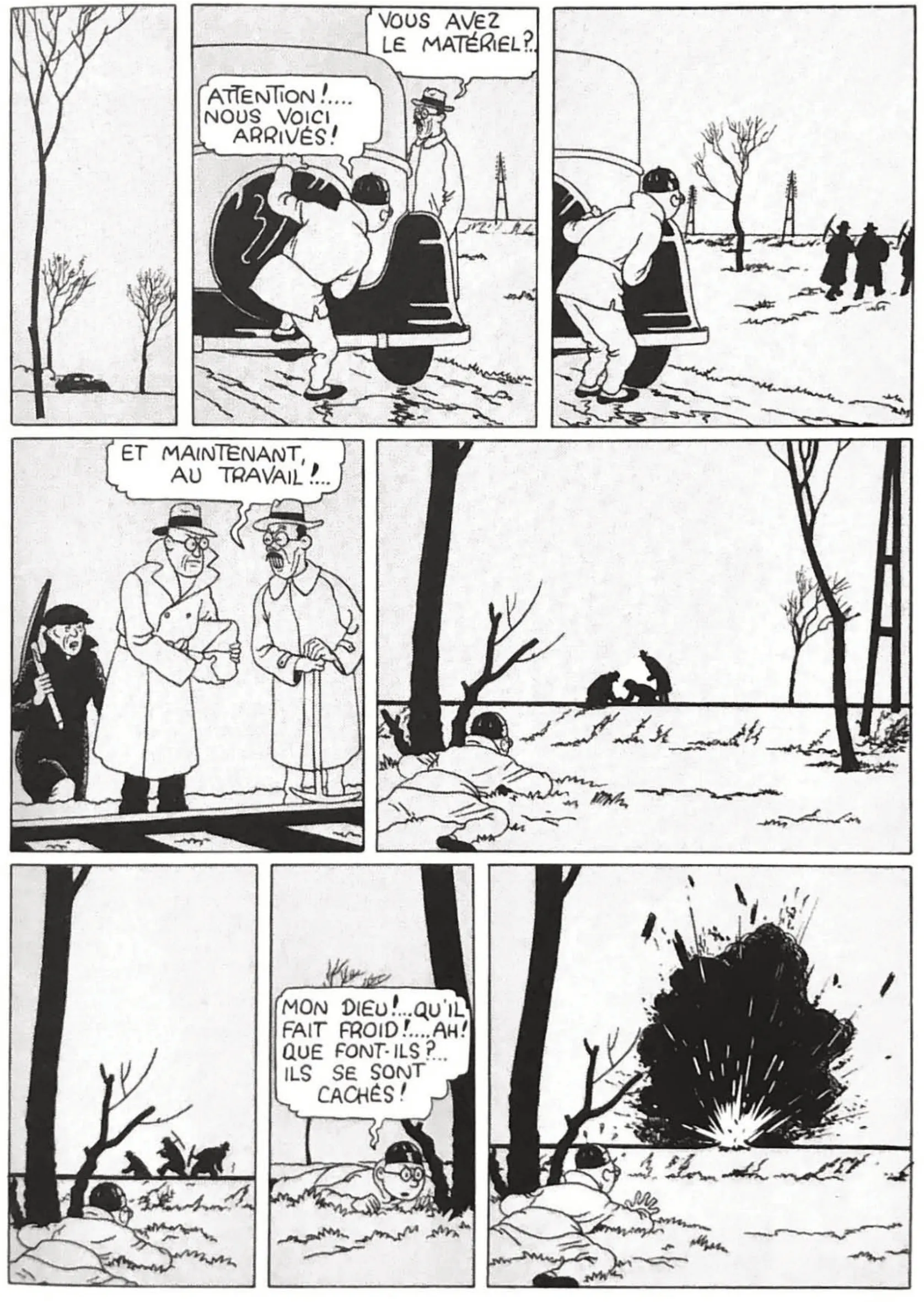

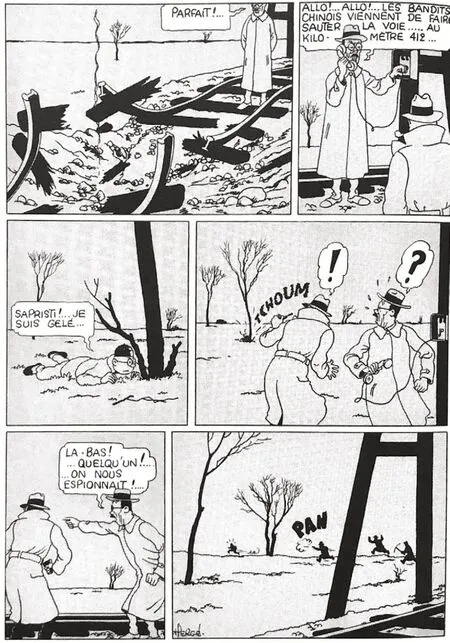

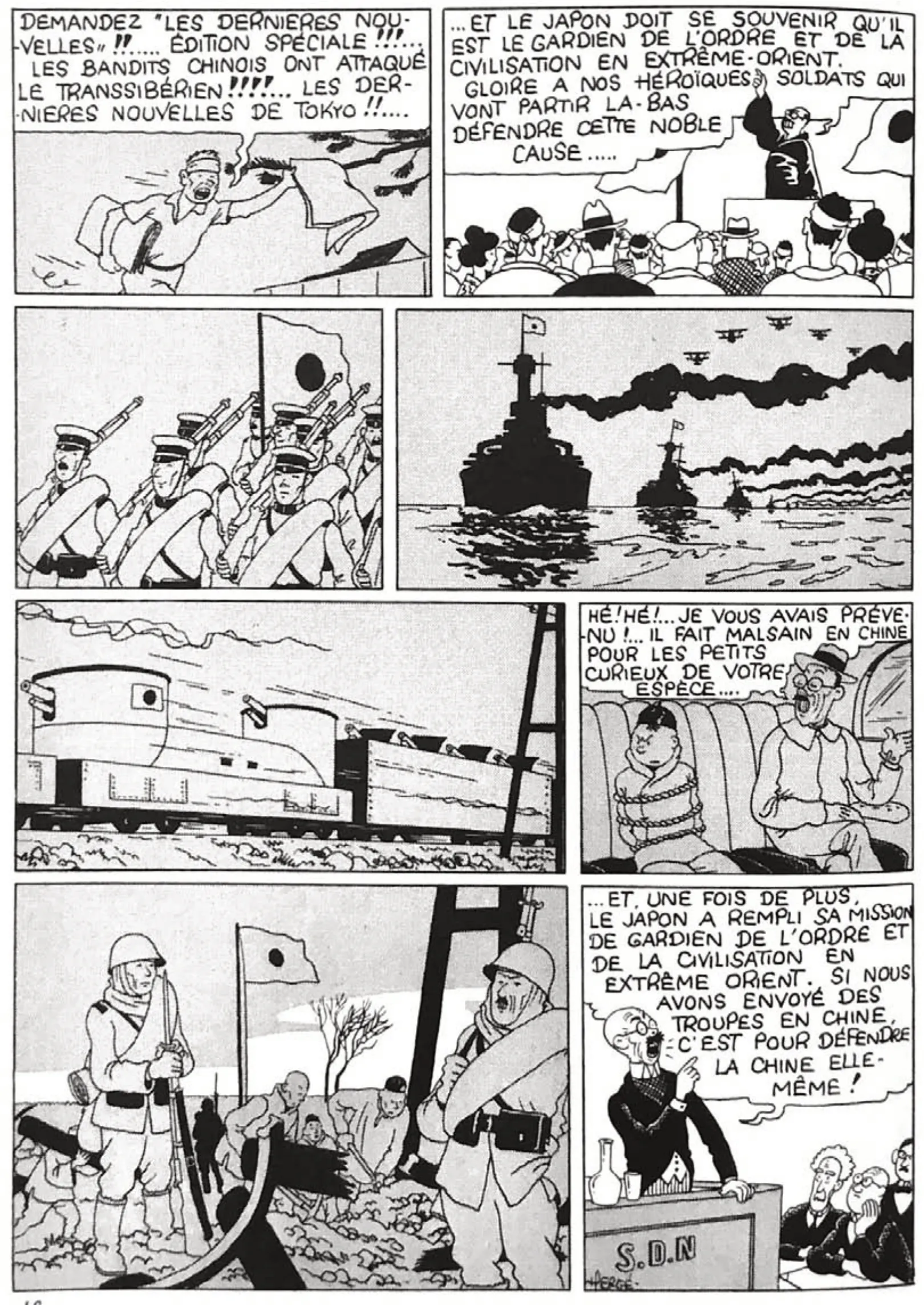

Continuing the theme of confronting international opium smuggling,which had started in the Middle East episode(CigarsofthePharaoh),TheBlueLotusvoiced its position in a new theme,the ongoing Sino-Japanese conflict.On September 18,1931,the Mukden Incident broke out in Shenyang,as the pretext for the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.In the comic,Tintin became an on-the-spot witness of the bombing of the Shanghai-Nanjing railway (due to the setting of the story,it did not take place exactly in Shenyang as the Incident itself) and overheard the Japanese plotting to invade.Deliberately planning to blame it on China,the Japanese immediately spread the exaggerated and distorted news worldwide through media that: “The effrontery of Chinese guerillas knows no bounds! News just in details a treacherous attack on the Nanjing-Tianjin (note here the rail changed from Shanghai-Nanjing to Nanjing-Tianjin,later even became the Trans-Siberian) railway having blown up the track,the brigands stopped the train and attacked the innocent passengers.Reports tell of many killed trying to defend themselves.Twelve Japanese died.After the attack the bandits,numbering more than a hundred,fled with their loot.” Based on such a groundless claim to justify its military deployment in China,Japan stated at the League of Nations that: “…and,once again,Japan has fulfilled its mission of guardian of order and civilization in the Far East! If we have,to our great regret,to send troops to China,it is to defend China itself!” (fig.7.1-4)32Hergé, 43-46.

Taking into account the public opinion in Europe towards the Sino-Japanese conflict in the early 1930s,such explicit exposure of deception and injustice was rarely seen.In 1932,the diplomatic reports were sent from the Chinese Embassy in Belgium to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China: “since Japanese troops invaded Northeast[China],although efforts were made to communicate with the news presses,most of them are pro-Japanese,influenced by the French pro-Japan opinions.Only the Socialist party newspaperLePeupleand the religious [Catholic] partyLaLibreBelgiquecan speak fairly.The editorial of August 22[1932] inLePeuplefurther exposed the deceptive behaviour of the Japanese.”33罗怀:《驻比使馆呈文》,布鲁塞尔:中华民国驻比使馆,1932 年8 月28 日。[ LUO Huai, “Zhubi Shiguan Chengwen” (Report from Embassy in Belgium), Brussels: China Embassy in Belgium, August 28, 1932, Diplomatic Archives,Academia Sinica.]As for the Belgian government,it did not immediately announce its standpoint after the Mukden Incident.According to reports inLeSoirin 1932,there was “no precise statement on the subject of what will be the attitude of Belgium” as prior to a debate in the League of Nations,“it does not seem that Belgium has to take a position.”34“La Note Amerciaine et la Belgiuqe” (The American Note and Belgium), Le Soir, January 9, 1932, Diplomatic Archives,Academia Sinica.

Shortly after the Japanese invasion,Western powers tended to accept it as a fait accompli,mainly considering their own interests instead of the principle of justice.According to research by John F.Laffey,in the 1930s France tolerated the Japanese invasion despite the fact that it violated the treaty structure arranged at the Paris Peace Conference and the Washington Naval Conference,because of French interests in Indochina.Laffey summarized that: “Quai d’Orsay recognized the paramount significance of the existing agreement,but with the important qualification that France had no interest in a stronger China.” France was against any change which would constitute an immediate danger on the frontier of Indochina.Thus,it preferred to maintain an amicable relationship with Japan,and even offered capital to Japan for the development of Manchuria in 1932.35John F.Laffey,“French Far Eastern Policy in the 1930s,” Modern Asian Studies 23, no.1 (1989): 117-49.

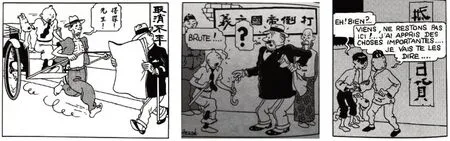

The distinctive stance taken inTheBlueLotuswas thanks to a conversation between Zhang and Hergé.As recalled by Zhang,he explained to Hergé the background of the Sino-Japanese conflict,telling him that it was Japan that created incidents as pretexts to invade China,but falsely accused China of creating them.Japan projected itself as maintaining order in the Far East for the common good,but,Zhang thought,it only cared for its own benefit.Inspired by the details which he had been unaware of,Hergé formulated the idea that Tintin would expose the Japanese conspiracy to the audience,making it known in Europe.36张充仁:《自述传记(节选)》,第202 页。[ZHANG Chongren, “Zishu Zhuanji (Jiexuan) ” (Autobiography [Selected]),202.]The intention to denounce inequality and injustice could be seen elsewhere in the comic: there are slogans and banners declaring the anti-imperialism and the abolishment of unequal treaties (fig.8).Hand-written by Zhang,the meaning was clearly known to Hergé: “many of the texts,those on the posters,for example,are starkly anti-Japanese.”37Hergé and Sadoul, Tintin et moi, 131.Decades after its publication,Hergé maintained the political position of the comic and commented that: “[it] was actually not intended for young readers,but their elders”.38Hergé and Sadoul, 71-72.

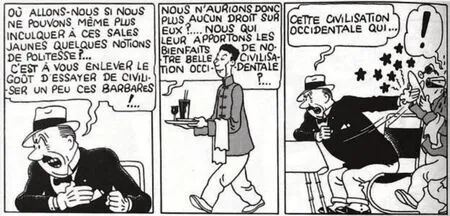

If Chinese characters made it difficult to convey the whole message to European readers,Hergé dedicated a scene to expose the problem of Western self-approving superiority.He sarcastically made the businessman Mr.Gibbons claim that: “Where are we heading if we cannot even instil some notions of politeness in these dirty yellows? It really puts you off to civilize a bit these barbarians! Would we thus no longer have any right over them? We,who bring them the benefits of our beautiful western civilization?”(fig.9).39Hergé, Le Lotus Bleu, 16.It was a clear message to ask the audience to re-examine the Eurocentric paternalist attitude towards another country,with which colonial and imperial gestures often prided themselves onmissioncivilisatrice[civilizing mission].

Figure 7.1 Tintin witnessed the bombing of the Shanghai-Nanjing Railway by the Japanese.

Figure 7.2 When Mitsuhirato was to report that the railway was blown up by Chinese bandits, Tintin accidently exposed himself to the Japanese.

Figure 7.4 Japan deployed its army in the name of “fulfilling its mission of guardian of order and civilization in the Far East.” Its representative at the League of Nations claimed that “to send troops to China, it is to defend China itself.” Tintin was firmly held captive.Images from Le Lotus bleu.

Figure 8 Left, “Abolish unequal [treaties]”; middle, “Down with imperialism”; right, “Boycott Japanese goods.” Images from Le Lotus bleu.

Figure 9 Scene of Mr.Gibbons complaining about “civilizing the Chinese.” Images from Le Lotus bleu.

In the geopolitical tensions in the 1930s,TheBlueLotusevoked immediate reactions from both the Japanese and Chinese authorities.As soon as the scene in which Tintin witnesses Japanese bombing appeared in the newspaper,the director ofLeVingtièmeSièclereceived Japanese objection to the depiction of Japanese policy in China inTintinfrom Lieutenant-General Raoul Pontus,40Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, 79.who had been the president ofl’InstitutBelgedesHautesÉtudesChinoises比京中国高等学术研究院 (The Belgian Institute of Higher Chinese Studies) since 1929,and was co-organizer of the “New China” section of the Chinese presentation at the 1935 Brussels Expo.41《颁给比利时人员勋章》。[ “Bangei Bilishi Renyuan Xunzhang,” (Diplomatic Honours to Belgians) n.d., Diplomatic Archives, Academia Sinica.]Hergé recalled General Pontus as saying: “This is not for children,what are you talking about[...] It is all the problem of East Asia!” Despite pressure from Japan,Hergé and Zhang insisted on keeping the original storyline ofTheBlueLotus.

Meanwhile,the first lady of the Republic of China,Song Meilin 宋美龄 (Soong Mei-ling,Madame Chiang Kai-shek,1898-2003) also learned of it.On December 7,1939,a telegram from Chongqing from the Vice Minister of Information,Dong Xianguang 董显光 (Hollington Tong,1887-1971),read: “Madame Chiang invites Hergé.Reimbursement provided.” According to the biographer Benoît Peeters,the real intention of this telegram was to invite Hergé to draw for the educational sector of the Chinese government,probably in a weekly for Chinese youth.42Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, 105.In the end Hergé could not go,because he was doing military service.A few days later,Germany launched attacks on Belgium and began its occupation which lasted for the next five years.43Peeters, 106-7.In 1973 Hergé finally visited Taiwan on a government invitation and he was awarded a Golden “Lei” medal 金罍奖章 by the Taiwan“National” Museum of History,in recognition of his support of China during the Sino-Japanese conflict inTheBlueLotus(fig.10).44《史物馆以金罍奖章赠比国漫画家艾善》。[ Shiwuguan Yi Jinleijiangzhang Zeng Biguo Manhuajia Aishan (Golden“Lei” Medal Awarded by the “National” Museum of History

Figure 10 “Golden ‘Lei’ Medal Awarded by the ‘National’ Museum of History (Taiwan) to the Belgian Cartoonist Hergé.” Photo by author at Musée Hergé (September 2017).

However,recently some contemporary readers,unaware of the historical situations of the 1930s,have asked whether the comic provokes racism and questioned the representation of China and Japan.A comment in French via the reviewing platform of the “Tintin” App45The “Tintin” App (iOS and Android) was launched in 2014, which houses the digital version of whole collection and keeps adding new language versions.“TINTIN / The Adventures of Tintin APP,” http://en.tintin.com/news/index/rub/0/id/5046/0/the-adventures-of-tintin-app, [August 31, 2019].noted:“as soon as Tintin is on Chinese soil,all foreigners are in the camp of the wicked and all Chinese are in the camp of the good guys! [...] The representation of the Chinese world is remarkable;the Japanese are ridiculous.”46helun, “Review of The Blue Lotus,” The Adventures of Tintin App, July 8, 2018.As also noticed by Alexander Laser-Robinson,in contrast to the sympathy shown by Tintin to Chinese people inTheBlueLotus,Hergé caricatured the Japanese.47Alexander S.Laser-Robinson, “An Analysis of Hergé’s Portrayal of Various Racial Groups in The Adventures of Tintin,”Euonymous 2005-2006, n.d., https://www.tintinologist.org/articles/analysis-bluelotus.pdf.In fact,TheBlueLotuswas among the last albums to be translated into English,because the British publisher,Methuen,considered that it might offend Japanese readers.The English translators Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper confided in an interview with the“Tintinologist” correspondent Chris Owens in 2004 that there were “considerable fears about how the Japanese would take it.” Therefore,its publication was held back until 1983.48“Exclusive Interview with Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper | Tintinologist.Org,” http://www.tintinologist.org/articles/mt-llc-interview.html [ August 31, 2019 ].

Hergé and Zhang had their own perspectives on this issue: the intention of the comic was not a criticism of Japan,but of injustice.In the 1970s,Hergé explained about morality and race in his work,and said: “Tintin has always sided with the oppressed,” adding “I showed a lot of‘villains’ of various origins,without making a particular kind to a particular race.”49Hergé and Sadoul, Tintin et moi, 71, 91.In the 1980s,Zhang explained his understanding ofTheBlueLotus: “It does not mean hatred of Japanese but is a protest against bullying.”50张充仁:《往事片段》,见张充仁纪念馆、上海张充仁艺术研究交流中心:《张充仁艺术研究系列3:文论》,上海:上海人民美术出版社,2010 年,第206 页。[ ZHANG Chongren, “Wangshi Pianduan (Fragments of the Past),”in Wenlun(Selected Essays on Zhang Chongren), ed.Zhang Chongren Jinianguan, Shanghai Zhang Chongren Yishu Yanjiu Jiaoliu Zhongxin (Zhang Chongren Museum and Shanghai Research and Communication Centre of the Arts of Zhang Chongren),Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2010, 206.]Eventually,according to the English translators,it turned out that the Japanese acceptedTheBlueLotuscompletely.51“Exclusive Interview with Michael Turner and Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper | Tintinologist.Org,” http://www.tintinologist.org/articles/mt-llc-interview.html [August 31, 2019 ].

Since the comic is “politized” to some extents,for some it is still questionable,whether the Hergé-Zhang communication was a cultural dialogue or a political propaganda,hence eliciting some conspiracy plot as mentioned earlier.If one looks beyond the theme of politics into other features in the comic,it is clear that their conversation was not indoctrination.The initiative to break with cultural stereotypes is a case in point.

III.Breaking with the Stereotype

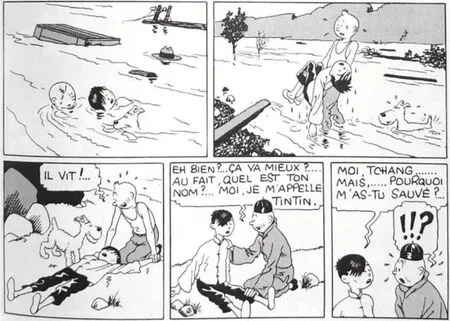

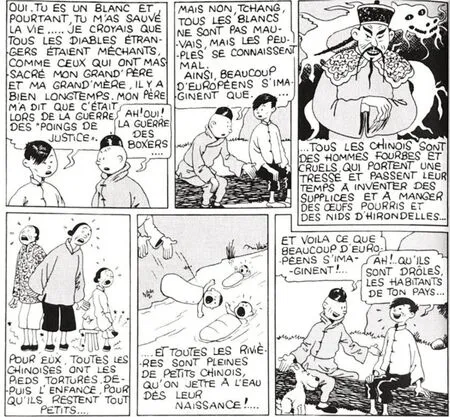

-Well?Better?Bytheway,whatisyourname?MynameisTintin.

-Me,Tchang.But...Whydidyousaveme?

-Yes.Youareawhiteman,andyetyousavedmylife...Ithoughtalltheforeigndevilswereevil,likethosewhoslaughteredmygrandfatherandgrandmotheralongtimeago.Mydadtold meitwasduringthewarofthe“fistsofjustice.”

-Ah!Yes!TheBoxerWar.Butno,Zhang,notall“whites”arebad,butpeopledonot knoweachotherwell.Also,manyEuropeansimaginethatallChinesearewickedandcruel men,whowearabraidandspendtheirtimeinventingtorturesandeatingrotteneggsand swallownests.Forthem,alltheChinesewomenhavehadtheirfeettorturedsincechildhood,so thattheyremainverysmall.TheyareevenconvincedthatChineseriversarefullofunwanted babies,throwninwhentheyareborn.So,youseeTchang,thatiswhatlotsofpeoplebelieve aboutChina!

- [Bothlaugh]Theymustbecrazypeopleinyourcountry!

In a light-hearted way,the dialogue between Tintin and Tchang showed how nonsensical the mutual stereotypes of Europeans and Chinese are,but to overcome an established perception was not a light issue.Examining the vague caricatures that appeared in previousTintinand other contemporary comics help to make sense of the prevailing stereotypes of China of that time,which foregrounds the uniqueness of the presentation inTheBlueLotus.

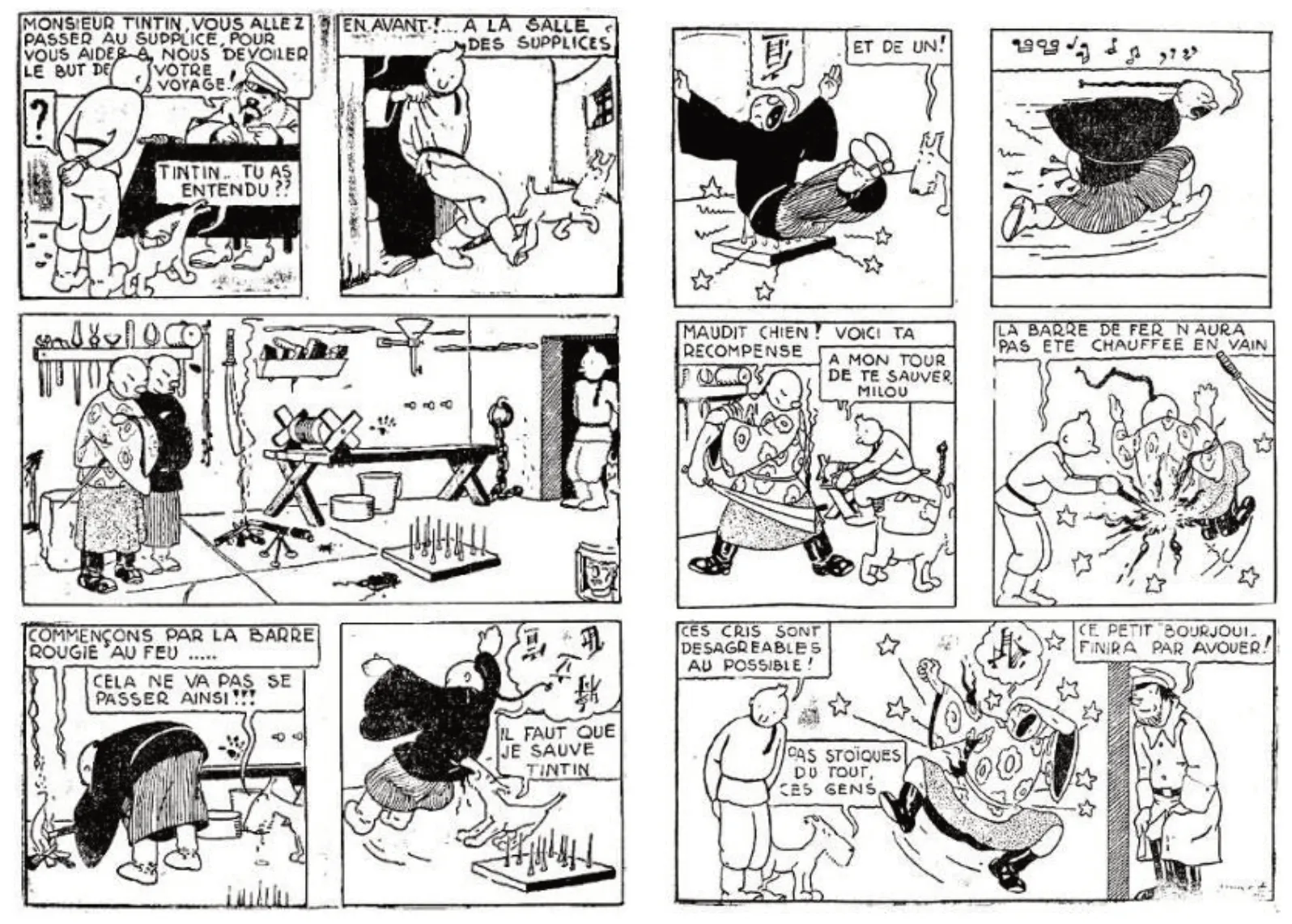

In the first Tintin story set in the Soviet Union,there appeared two Chinese people.They looked alike except for the differences in their clothing: the same appearances and the same role to torture Tintin (fig.11).52Hergé, Les aventures de Tintin au pays des soviets (The Adventures of Tintin in the land of the Soviets), Les Aventures de Tintin 1 (Tournai: Casterman, 1930), 66-67.In the 1930s,there were not many comics concerning China,while those that mentioned it presented Chinese people in the same caricatured manner.For instance,inBiboretTribar(Bibor and Tribar) by Rob-Vel (1938),the two French sailors,Bibor and Tribar,came across ordinary Chinese people and mandarins wearing braids,having slanted eyes and dressed in traditional-looking costumes.They are presented in the same stereotype as inTintin inthelandtheSoviets(fig.12).After analysing comics about China during that period,Kim Yong-ja said in summary that “the image of China appears both ambiguous […] and distorted by anachronism and exoticism.”53Kim Yong-ja, “Le Chinois dans la Bande Dessinée et la Caricature de la Presse Européenne Francophone durant l’entre-Deux-Guerres,” in Stéréotypes Nationaux et Préjugés Raciaux aux XIX et XX° Siècles: Sources et Méthodes pour une Approche Historique, Université Catholique de Louvain 24 (Louvain-la-Neuve/Leuven: Bureau du Recueil, 1982), 117-33.

Figure 11 Chinese people in The Adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets.Images from Les aventures de Tintin au pays des soviets.

Figure 12 Chinese people in “Bibor et Tribar” (Bibor and Tribar), by Rob-Vel in Le Journal de Spirou(The Journal of Spirou) (1938).Images from Stéréotypes nationaux et préjugés raciaux aux XIX et XX siècles.

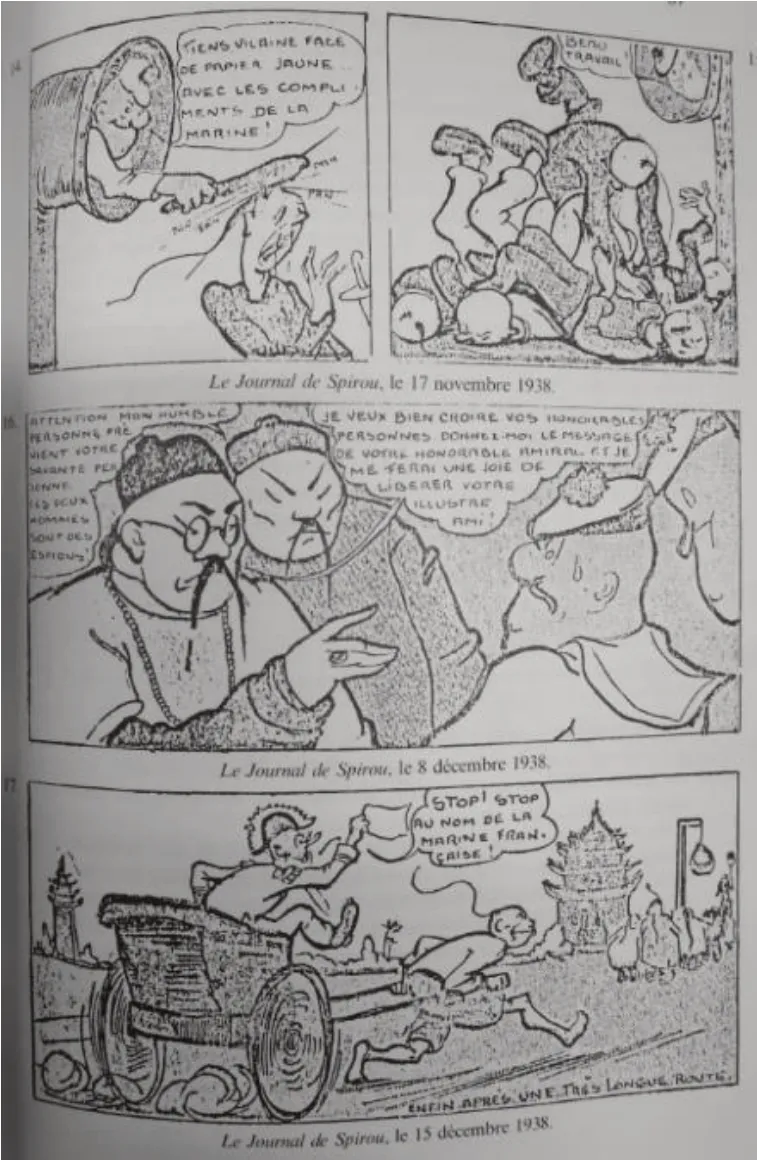

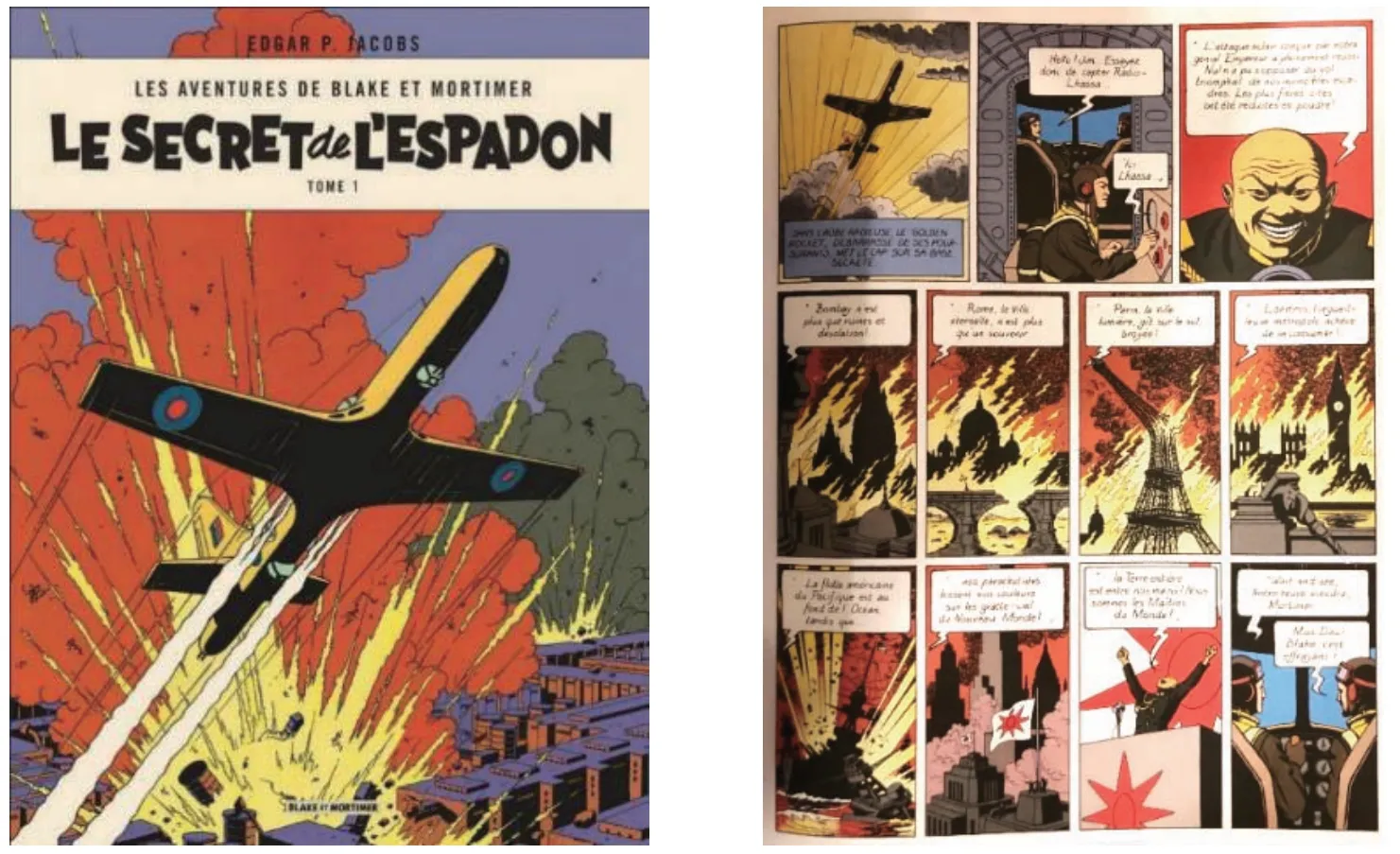

Even over a decade afterTheBlueLotus,the presentation of Chinese/Asian people remained the same,despite a huge leap in the drawing technique,for example,LesAventuresdeBlakeetMortimer(Blake and Mortimer) which came out in 1946 and was created by Edgar P.Jacobs.The comic was about the adventures of Philip Mortimer,a leading British scientist,and his friend Captain Francis Blake of MI5.Its first story,LeSecretdel’Espadon(The Secret of the Swordfish),created an enemy of the “free world,” the “Yellow Empire.” In the story,the“Yellows” were about to launch a worldwide aggression and destroy the free world.54Edgar P.Jacobs, Le Secret de l’Espadon (The Secret of the Swordfish), Blake et Mortimer 1 (Brussels: Éditions du Lombard, 1946).The facial features and the cruel personality of the “Yellows” did not vary much far from the two Chinese people inTintininthelandtheSoviets(fig.13).Benoît Peeters points out that: “inBlakeand MortimerandBuckDanny(Les Aventures de Buck Danny)[…] it would still be nothing but‘the Yellows’ and ‘lemon faces’ for a long time to come.”55Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, 77.

Figure 13 The Yellow Empire as the villain in the bande dessinée The Adventures of Blake and Mortimer.Image from Le Secret de l’Espadon (1946).

Taking into consideration a common perception of China at that time helps to make sense of the early image of China inTintin.The notion of “Yellow Peril” from the late nineteenth century spoke of the anxiety that people from the East are a danger and threat to the Western world.56John Kuo Wei Tchen, Yellow Peril!: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear, ed.Dylan Yeats (London: Verso Books, 2013).The Boxer Movement in 1900 reinforced the stereotype.The Getty Research Institute holds one of the largest collections of China photography in the United States.Having studied the holdings,Sarah E.Fraser argues that between 1860-1920 “China” became a popular object of spectatorship,created by professional photographers and consumed by Western audience,but it was framed through violence and submission: “the captions note class and racial qualities,and the images are often explicitly violent.”57Sarah E.Fraser, “The Face of China: Photography’s Role in Shaping Image,1860-1920,”Getty Research Journal 2(2010): 39-52.One of the examples she chose to illustrate her point was a photograph of a group of Boxers.Colin MacKerras has studied the ways in which Westerners have perceived China by analysing sources from the media.Concerning the Boxer Movement,he points out that: “the main images of the Chinese to emerge from the literature spawned by the Boxer uprising are cruelty,treachery,and xenophobia.”58Colin Mackerras, Western Images of China (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 60.

The stereotype had an impact on popular culture and was reproduced by it.As shown above,Edgar P.Jacobs drew a story on the threat to the “free world” coming from the “Yellow Empire.”During the same period,a more influential fictional villain is Fu Manchu 傅满洲by Sax Rohmer,who was portrayed as an evil criminal mastermind.Ruth Mayer,Jenny Clegg and Christopher Frayling have studied how this character gives shape to the persistent Yellow Peril myth and how it was related to the rise of Sinophobia.59Ruth Mayer, Serial Fu Manchu: The Chinese Supervillain and the Spread of Yellow Peril Ideology (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013); Jenny Clegg, Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril: The Making of a Racist Myth (Staffordshire: Trentham,1994); Christopher Frayling, The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & the Rise of Chinaphobia (London: Thames & Hudson, 2014).

Hergé initially reacted in the same way.He said that he “had been impressed by images and stories of the Boxer Movement,where the focus was always on the cruelties of the Yellows,”which had a strong impact on him.60Hergé and Sadoul, Tintin et moi, 60-61.It explains his depiction of cruelty in the Tintin Soviet story.Just a few years later,inTheBlueLotus,the visual difference of Chinese people is remarkable.

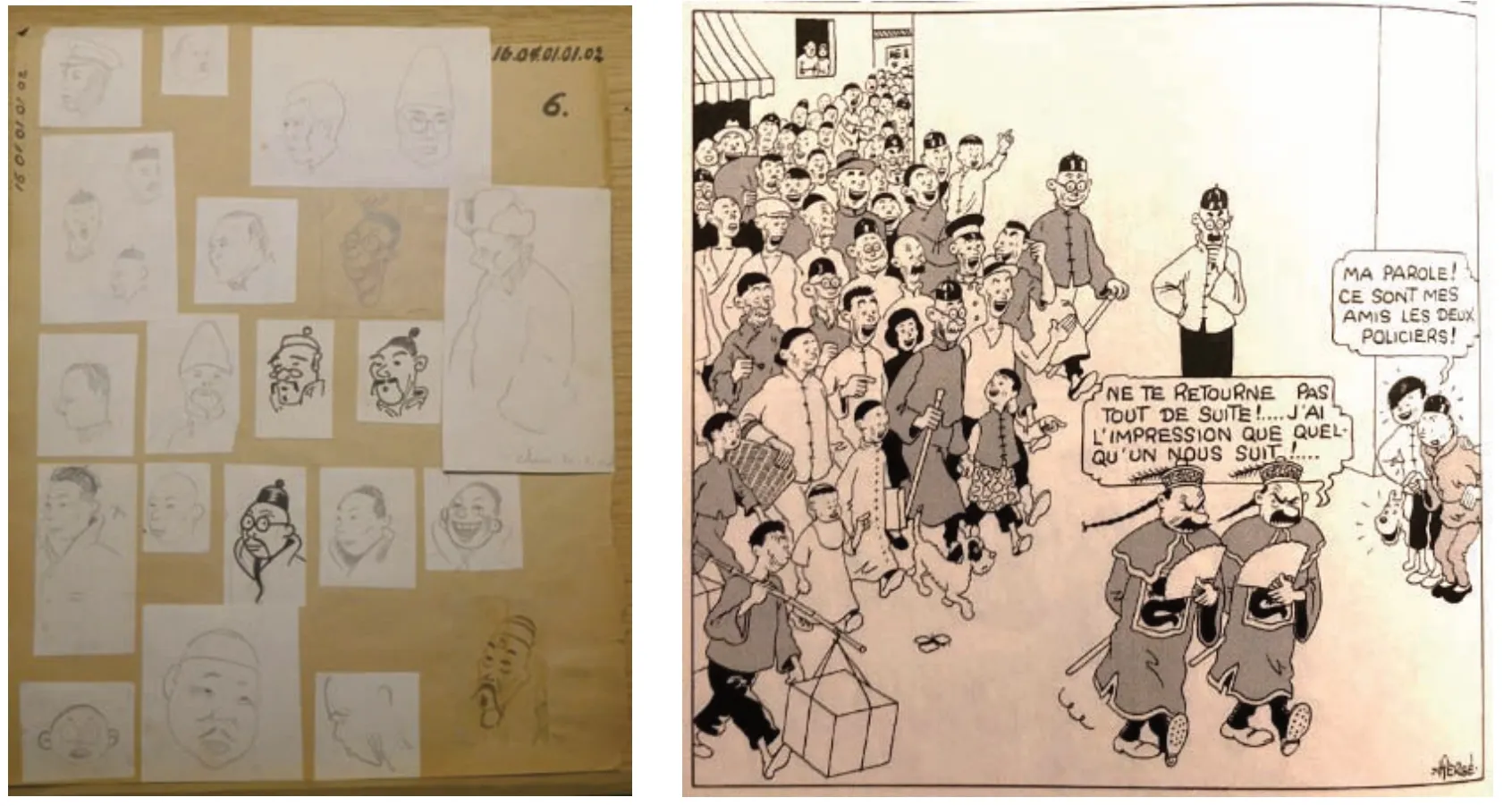

As shown in the preparatory sketches for the comic below,there were studies of precise variations of Chinese people,showing all kinds of facial features and attire,which contributed to the making of distinctive Chinese figures in the story.On top of that,TheBlueLotusspecifically devoted a dramatic and hilarious scene to make fun of people still unaware of stereotypes.In the scene,two European policemen,Dupont and Dupond,believed that they were in perfect disguise among Chinese,by wearing out-dated and exaggerated costumes.Their self-approval contrasts with the reality that they became a laughing stock.The locals were depicted here with rich individual differences,providing another visual contrast to the identical appearances of the two policemen (fig.14).In this respect,the originality of these changes and the changes themselves are both striking in comparison.

Figure 14 Left, sketches of figures; right, the “stereotype” scene.Photo by author at Musée Hergé(September 2017) and image from Le Lotus bleu.

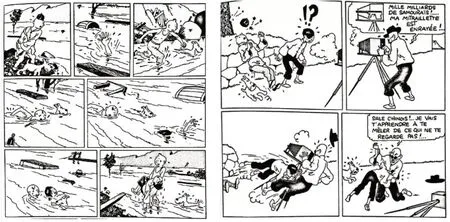

Not only the presentation of figures aimed to be genuine,but also the relationship with people in the comic shows reciprocity and sincerity.In Shanghai,Tintin’s personality reveals a more humane and cooperative side.Unlike previous stories where Tintin dealt with dangers by himself,in China Tintin worked with Chinese people.It is a reciprocal collaboration: while he had saved Tchang from being drowned,he was later saved by Tchang from being shot (fig.15).Chinese people inTheBlueLotuswere no longer cruel and primitive as in the Soviet story;instead they were kind and smart,showing the same qualities as Tintin.

Figure 15 Left, Tintin saved Tchang from the river; right, realizing the man disguised as a photographer was part of a trap to kill Tintin, Tchang fought to stop him from pulling the trigger.The Japanese bandit said “Damn! My machine gun is jammed!” and “Filthy Chinese! I am going to teach you to mind your own business!” Images from Le Lotus bleu.

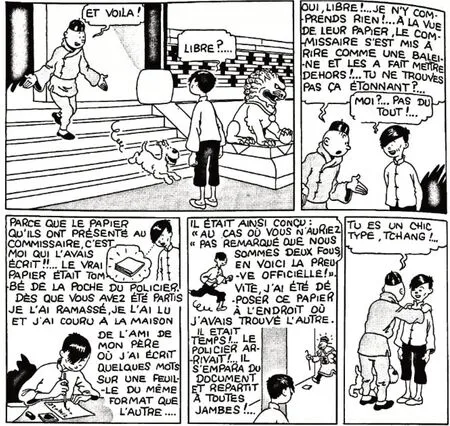

Tintin relied on their local knowledge to tackle difficulties.A scene shows how Tchang used his wit and ability to save Tintin after he was detained by the two policemen Dupont and Dupond.The policemen obtained a warrant written in Chinese for the arrest of Tintin,but they accidentally dropped the paper.Tchang noticed it,picked it up and replaced it with another one written in Chinese that “in case you have not noticed,we are lunatics and this proves it.”Retrieving the paper but unaware of the substitution,Dupont and Dupond handed it in to the local Chinese superintendent,who laughed out and immediately released Tintin after reading it.When Tchang explained what had happened and cleared his confusion,Tintin grasped Tchang’s shoulders with both hands and exclaimed: “What a great fellow you are,Tchang!” (fig.16)

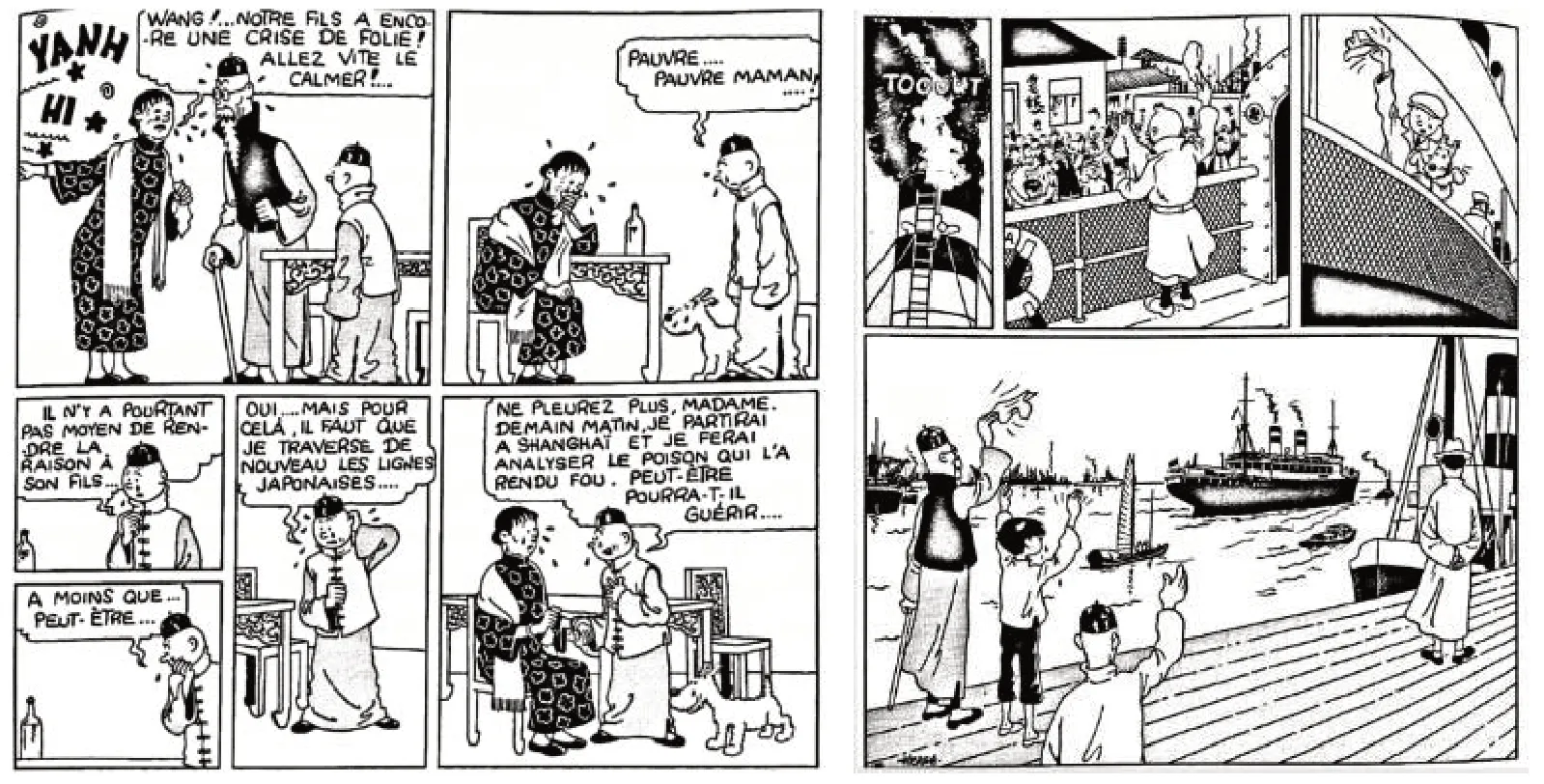

Towards the end,Tintin and Tchang became such close friends that Tintin was in tears when he had to leave Shanghai.Although it is not so precise as Harry Thompson claimed that “Chang[Tchang] is the only character Tintin ever cries for,”61Thompson, Tintin.Tintin did weep very rarely throughout his twenty-four adventures over forty-eight years and he did it twice inTheBlueLotus(fig.17).62Twice for his dog Milou, as he thought he had lost it (Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Flight 714).Twice in The Blue Lotus.Twice again for Tchang in a later story, Tintin in Tibet (1960), when he learnt that Tchang had disappeared after a plane crash and when he finally found him.

Figure 16 Tchang explained to Tintin why he was immediately released by the local superintendent.Image from Le Lotus bleu.

Tintin has never been that emotional,nor been that close to local people in places he travelled to in previous adventures.In the trip to the Congo—then a Belgian colony—Tintin hired a local boy,Coco,to assist him in his travels.Jean-Marie Apostolidès criticized the fact that Tintin possessed such a dominating and imposing attitude towards the Africans that: “Coco teaches him nothing about the country.Faced with his master’s raised finger,Coco always responds: ‘Yes,Master.’ The little African is assigned only menial tasks: watching the car,preparing the meals,and carrying their equipment.”63Apostolidès, The Metamorphoses of Tintin, 13.Judged by contemporary readers today,the Congo story has a strong racist and colonial tone,for which it was strongly criticized,even triggering campaigns to ban it around 2010.64Sarah Rainey, “Tintin: List of ‘Racist’ Complaints,” November 3, 2011, sec.Culture, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/booknews/8866997/Tintin-list-of-racist-complaints.html;“Ban‘Racist’ Tintin Book, Says CRE,” May 2009,https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1557233/Ban-racist-Tintin-book-says-CRE.html;“Tintin: Heroic Boy Reporter or Sinister Racist?”May 2010, http://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1986416,00.html;“Effort to Ban Tintin Comic Book Fails in Belgium,” May 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/law/2012/may/14/effort-ban-tintin-congo-fails.Speaking in defence,Michael Farr argued that it was created in 1931 when colonialism was the common practice.65Pascal Lefèvre,“The Congo Drawn in Belgium,”in History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels, ed.Mark McKinney (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008).

Figure 17 Left, seeing that Mrs.Wang is weeping over the madness of her son, Tintin cried with sympathy (“poor poor Mom”) and comforted her that he would try to find a cure for her son; right,tearful parting with Tchang and Mr.Wang at the dock.Images from Le Lotus bleu.

In sum,compared with the previousTintinand in the context of contemporary comic works,TheBlueLotuspays attention to precision instead of approximation of the setting,and overcomes the colonial ideologies found in earlier works.It presents China in a sharply different way from the common stereotype of barbarity and makes Chinese characters more active and humane,so much so that the relationship between Tintin and local people becomes equal and reciprocal.Benoît Peeters described the comic as “exceptionally moving”66Peeters, Hergé, Son of Tintin, 76.and Laurence Vanin sees it as a work “to rethink the differences and to meditate tolerance [...] [and] resolve the shortcomings of the ethnocentricity.”67Laurence Vanin, Tintin & Hergé: une aventure de la pensée!, 1 vols, Essais (Valence-d’Albigeois: Éd.de la Hutte, 2013).

It was the dialogue with Zhang about different cultures,people and civilizations that prompted Hergé to break with cultural stereotypes and study a civilization different from his own.As quoted in the beginning,Hergé was grateful for Zhang’s introduction of Chinese philosophy and arts.Retrospectively reviewing his influences in the course of his career,Hergé commented that: “He[Zhang] made me discover and love Chinese poetry,the Chinese [literary] writing[…] For me,it was a revelation.” Saying that Zhang introduced to him a civilization of which he had been completely ignorant,Hergé thought it made him realize that he should be careful and responsible for what he drew,for the sake of honesty vis-à-vis those who read him.68Hergé and Sadoul, Tintin et moi, 61.

Such impact went beyondTheBlueLotus,and became his awareness in the presentation of any other cultures inTintin.He said to Peeters in 1977 that: “I think that Zhang was,without knowing it,one of the artists who had the most influence on me […] it was he who made aware of the absolute necessity of being well informed about a country […].”69Hergé, Hergé In His Own Words, ed.Dominique Maricq (Brussels: Éditions Moulinsart, 2010), 30.Ann Miller summarized: “Famously,after his meeting with Tchang Tchong-Jen [Zhang Chongren] [...]Hergé began an almost obsessive concern with documentary accuracy in his depiction of the locations into which he sent his heroes.”70Ann Miller, Reading Bande Dessinee: Critical Approaches to French-Language Comic Strip (Bristol: Intellect Books,2007), 30.Hergé himself became more open-minded towards other cultures and people too,as he said: “more and more,I strive to know and understand,to break barriers,literally and figuratively.If I started to travel[…] this was not only to see new landscapes,not only to get documents,but to discover other ways of living,other ways of thinking; in sum,to expand my worldview.All this is partly owed to Zhang.”71Hergé and Sadoul, Tintin et moi, 92.

Thus,the cross-cultural dialogue facilitatedTheBlueLotusto overcome the common stereotype of “Yellow Peril”; the Hergé-Zhang friendship endowed the characters in the story a relationship of mutual trust and respect; the revelation inspired Hergé to develop on his worldview and gaveTintina sense of cultural awareness.In the final section,a brief review of the publication history ofTheBlueLotuswill be given,before a discussion of how readers of later generations respond to the comic created more than two-thirds of a century ago.

IV.Lasting Legacy

International relationships and geopolitical situations have changed significantly since the creation of the comic.The contents of the Sino-Japanese conflict,for example,are no longer current events.It could be expected that readers of later generation foundTheBlueLotusoutdated.Yet its sales statistics and on-going discussions indicate that audience can still relate to it.

Through translations and reprints,TheBlueLotustogether withTintinreached a large audience from generation to generation.In 1946,Hergé reformatted and coloredTheBlueLotus.72Thompson, Tintin, 60.The following year,the colored version ofTheBlueLotuswas translated into Dutch (Deblauwelotus).By the early 1980s,it had been translated into most major European languages: Spanish (ElLotoAzul,1965),Italian (Ildragoblu,1966),Portuguese (OLotusAzul,1967),Finnish (SininenLootus,1972),Danish (DenBllotus,1974),German (DerBlaueLotos,1975),Icelandic (BlaiLotusinn,1977),Swedish (Bllotus,1977) and English (1983).73“The Blue Lotus - Translations,” http://en.tintin.com/albums/show/id/29/page/35, [ August 22, 2019 ].Tintinwas not officially translated into simplified Chinese until 2001 and was released by the China Children’s Press中国少年儿童出版社,though unofficial translations ofTheBlueLotus(Lan Lianhua蓝莲花/兰莲花) were already circulating in theLianhuanhua连环画 (comic strips) format from the 1980s.

According to the official fan website “Tintin,”TheAdventuresofTintinhave been translated in more than 110 languages and more than 250 million copies have been sold since 1929.74“Essentials about Tintin and Hergé,” http://en.tintin.com/essentiel#, [ August 30, 2019 ].A report inLeParisien(The Parisian) in 2016 based on sources at Casterman,the publisher ofTintin,stated that three million copies ofTintinwere sold each year,and the French version remains the most popular.TheBlueLotusis the third best-selling album,afterTintinintheCongoandTintininAmerica(partly due to their early publication).75“240 millions d’albums vendus”(240 millions of albums sold), leparisien.fr, September 27, 2016, http://www.leparisien.fr/culture-loisirs/240-millions-d-albums-vendus-27-09-2016-6152797.php, [September 27, 2016].A post created in 2005 from the largest English-language,non-official fan-site“Tintinologist” points out that 44% of French homes possess at least one album and almost 30% of French homes have the full series.76“Tintin Books: Sales Statistics-Tintin Forums,” https://www.tintinologist.org/forums/index.php?action=vthread&forum=8&topic=933, [ July 24, 2005 ].

SinceTheBlueLotusremains easily accessible to many households worldwide,it continues to be a topic of discussion.In the comment thread aboutTheBlueLotuson the website“Tintinologist,” there are remarks on whether it is suitable for children,whether it presented China in an objective way,and whether it is outdated.There are also appreciations of its artistry,story-telling,authenticity and the emotion embodied in the story.77“The Blue Lotus: General Discussion,” Tintin Forums, https://www.tintinologist.org/forums/index.php? action=vthread&forum=1&topic=525, [ August 31, 2019 ]; “The Blue Lotus: Was It Thought Suitable for Children? - Tintin Forums,”https://www.tintinologist.org/forums/index.php?action=vthread&forum=1&topic=1072, [ August 31, 2019 ].Summarizing these various criticisms and acknowledgements,Tara Jacob,another commentator onTheBlueLotus,concluded that despite the flaws and potentially misleading racist messages,the main values conveyed throughout the story are “tolerance,respect,and understanding of other peoples”;they will evoke readers’ sympathy for other cultures.This is the main reason thatTheBlueLotusremains relevant even today.78“Great Snakes! The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus-an Analytical Reading,” Tintinologist, http://www.tintinologist.org/articles/greatsnakes.html, [ August 31, 2019 ].

Audiences in China also related to the key message of understanding and sympathy,embodied in the friendship between Zhang and Hergé.AlthoughTintinhas never been as famous in China as in Belgium and France,it still has a considerable number of readers.In 2004,the programme “Dushu Shijian 读书时间 (Reading Time)” from the Number 10 China Central Television (CCTV 10) channel produced an episode titled “Dingding yu Zhongguo 丁丁与中国(Tintin and China),” which introduced the friendship of Zhang Chongren and Hergé,as well as praising the righteousness,wisdom and bravery of Tintin.The programme concluded that:“What moves us Chinese readers most is the sincere friendship between Tintin and his Chinese friend Tchang.When Hergé created these characters,he only had one Chinese friend,Zhang Chongren; now in China,how many friends does Tintin have? The number is probably too big to count.Their story and friendship will be like Tintin,forever young.”79《丁丁与中国》,央视网CCTV-10 科教频道节目,2004 年8 月24 日出品。[ “Dingding yu Zhongguo” (Tintin and China), produced August 24, 2004 in Beijing by CCTV 10, http://www.cctv.com/program/wrt/dssj/20040824/100921.shtml.]

In view of the responses,it could be said that based on the foundation of an in-depth crosscultural dialogue,there is an equal,reciprocal and empathic tone between the lines and the images throughoutTheBlueLotus.In this way,the comic conveys the lasting message of mutual understanding,which inspires readers of different ages,races and cultures to pursue it.