多巴胺系统多基因与青少年攻击行为的U型关系:母亲消极教养的调节作用*

林小楠 曹衍淼 张文新 纪林芹

多巴胺系统多基因与青少年攻击行为的U型关系:母亲消极教养的调节作用*

林小楠 曹衍淼 张文新 纪林芹

(山东师范大学心理学院, 山东省学生发展与心理健康研究院, 济南 250014)

多巴胺活性与攻击相关的脑功能活动呈倒U型关系。本研究对1044名汉族青少年(初次测评时M = 13.32 ± 0.49岁, 50.2%女生)的攻击行为进行间隔一年的两次测评, 采用多基因累积分范式考察多巴胺系统的多基因功能积分与青少年攻击行为间的关系以及母亲消极教养的调节作用。结果发现, 多巴胺系统多基因累积分二次项与母亲消极教养交互影响两个时间点的青少年攻击行为:在较高母亲消极教养条件下, 携带较多或较少低多巴胺活性相关等位基因的青少年表现出高水平的攻击行为, 呈U型关系; 在较低母亲消极教养条件下, 多基因累积分二次项与青少年的攻击行为关系不显著。本研究为多巴胺系统基因的联合效应与母亲消极教养调节青少年攻击行为的基因作用机制提供证据。

攻击行为, 母亲消极教养, 多巴胺系统, 多基因累积分, U型关系

1 引言

攻击是个体有意对他人身体或心理进行伤害的行为(Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), 7.48% ~ 24.3%的中国青少年具有较为严重的攻击或暴力行为(Wang et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2021)。青少年攻击行为不仅导致其学业失败、增加其罹患精神病风险和暴力犯罪行为, 还会造成巨大的社会经济和精神卫生医疗负担(Ansary et al., 2017; Estévez et al., 2018)。由于攻击行为的普遍性与危害性, 研究者从遗传因素和家庭教养方面探索攻击行为发生的基因−环境作用机制, 尝试提出个体化的攻击行为家庭预防方案。

1.1 多巴胺系统基因与攻击

多巴胺系统基因参与情绪调控、执行控制以及动机过程(Gatzke-Kopp, 2011; Nikolova et al., 2011; Tielbeek et al., 2018; Vrantsidis et al., 2021), 与个体的攻击行为密切相关(Albaugh et al., 2010; van Goozen et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016)。然而, 现有关于多巴胺系统基因与攻击行为间关联的分子遗传研究结果存在不一致。部分研究显示, 与低多巴胺活性相关基因型与攻击行为的增加相关联(Hygen et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2001; van Goozen et al., 2016)。譬如, van Goozen等(2016)发现与低多巴胺活性相关的基因rs4680位点Val等位基因与高攻击行为有关, Hygen等人(2015)的研究发现该位点Val纯合子携带者经历较多严重生活事件时表现更多攻击行为。然而, 也有研究显示Met等位基因与高攻击行为密切相关。例如, Albaugh等人(2010)发现基因Met等位基因(A等位基因)与高攻击行为存在关联, Zhang等人(2016)发现Met等位基因携带者在经历低水平积极教养时表现出更多反应性攻击。尽管研究者试图从样本特征、环境因素以及攻击测评方式角度对研究结果的分歧进行解释, 但是既有研究可能忽视了两个重要事实:(1)多巴胺系统单个基因作用微效, 多个基因存在联合与交互作用, 多巴胺系统遗传效应积分与攻击行为并非线性关系; (2)多巴胺系统基因的作用受环境因素的调节。

神经化学和心理遗传研究表明多巴胺系统基因与攻击行为间可能存在非线性关系。神经生化研究证据表明, 攻击行为相关脑功能与多巴胺活性间呈倒U型关系, 中等多巴胺活性水平下PFC及相关脑区的功能最优, 多巴胺活性过高或过低时PFC及相关脑区功能受损(Arnsten, 2009; Bertolino et al., 2009; Robbins & Arnsten, 2009; Seamans & Yang, 2004; Tian et al., 2013; Tunbridge et al., 2006)。心理遗传研究发现多巴胺系统基因对攻击行为相关脑区结构和功能的影响存在交互作用或非线性关系。例如, Bertolino等人(2009)探究了、基因与特定脑区活性的关联, 发现携带与高多巴胺活性相关的基因型组合(10R/10R和GG基因型)或携带与低多巴胺活性相关的基因型组合(9R和GT基因型)个体的尾状核和额中回活性较低、灰质体积更大, 而携带中等多巴胺活性相关基因型组合个体的尾状核和额中回活性、灰质体积处于正常水平。因此, 我们预期, 多巴胺系统基因与攻击行为间可能存在非线性关系。

1.2 多巴胺系统多基因的联合效应

近年来, 基于多基因假说的多基因累积分(multilocus genetic profile score, MGPS)日益受到重视。该方法通过累计多个基因位点获得多基因累积分, 揭示多个基因对某种心理或行为个体差异的贡献(Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022; Davies et al., 2019; Nikolova et al., 2011; Thibodeau et al., 2015)。

神经系统内多巴胺活性受到多巴胺能水平、受体效能和利用效率的影响。因此, 参与多巴胺降解、传导与转运的基因间的联合效应共同调节突触间隙内的多巴胺活性, 影响儿童青少年心理病理问题(Davies et al., 2019; Nikolova et al., 2011; Thibodeau et al., 2015)。儿茶酚胺氧位甲基转移酶(catechol- O-methyltransferase, COMT)、D2型多巴胺受体(D2 receptor, DRD2)和多巴胺转运体(dopamine transporter, DAT1)基因分别影响多巴胺的降解、传导与转运(Chester & DeWall, 2016; Nikolova et al., 2011), 共同调节多巴胺活性。基因编码儿茶酚胺氧位甲基转移酶, 负责降解多巴胺等单胺类神经递质。rs4680多态位点翻译产物中第158位氨基酸发生缬氨酸(valine, Val)到蛋氨酸(methionine, Met)的替换使COMT酶活性降低40% (Chen et al., 2004; Lotta et al., 1995; Meyer et al., 2016)。基因负责编码D2型多巴胺受体。该基因启动子区rs1799978(A-241G)多态性在-241位置处发生腺嘌呤(A)到鸟嘌呤(G)的基因转换, 与更多的多巴胺D2受体密度和转录水平有关, 进而影响多巴胺活性(Genis-Mendoza et al., 2018; Xing et al., 2007; Zhang & Malhotra, 2011)。基因负责编码多巴胺转运体。该基因3’端非翻译区rs27072位点T等位基因比C等位基因型具有更高转率水平, 从而在突触中更有效地重新摄取多巴胺, 减少突触间隙的多巴胺水平(Pinsonneault et al., 2011)。这三种基因在前额叶、纹状体和中脑等攻击相关脑区中表达水平更高(Yamaguchi & Lin, 2018)。已有研究发现, 这三个基因多态性位点与儿童青少年攻击行为密切相关(Chester & DeWall, 2016; Davies et al., 2015; van Goozen et al., 2016; Zai et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016), 协同影响攻击行为(Davies et al., 2019; Vrantsidis et al., 2021)。本研究拟选取和的上述三种高功能等位基因创建多基因累积分, 考察多基因累积分与攻击行为的关联。

1.3 母亲消极教养的调节作用

多巴胺系统基因对攻击行为的影响作用受环境因素调节, 即存在G × E交互作用(Beauchaine et al., 2007; Davies et al., 2019; Shanahan & Hofer, 2005)。生物发展模型(biosocial developmental model, BDM)指出, 重复暴露于不利教养环境会增加携带多巴胺功能缺陷基因个体发展出问题行为的风险(Beauchaine et al., 2007)。近期, Tomlinson等(2022)的双生子研究为此提供了证据支持, 他们发现, 温情(积极教养)减弱遗传因素对冷酷无情特质的影响, 但是遗传素质对冷酷无情的影响在严厉管教(消极教养)中更强。

家庭教养对儿童青少年攻击行为具有重要影响(Davies et al., 2019; Gershoff, 2002; Stocker et al., 2017; Thibodeau et al., 2015)。其中, 母亲对孩子的惩罚、拒绝与排斥等消极教养行为会使得儿童青少年出现对不良行为的模仿、增强敌意情绪情感及认知归因等(Gershoff, 2002; Goulter et al., 2020), 限制、阻碍情绪及行为调节功能发展等(Ganiban et al., 2021; Thibodeau et al., 2015), 进而促进攻击行为发生(Zhang et al., 2016)。既有研究揭示, 消极教养与多巴胺系统多基因交互影响儿童青少年攻击相关行为, 如反社会行为、外化问题等(Davies et al., 2015, 2019; Thibodeau et al., 2015)。譬如, Davies等(2015, 2019)的研究发现, 多巴胺系统多基因累积分与母亲非敏感性等消极教养交互预测个体的外化问题, 携带与较低多巴胺活性相关等位基因的个体在经历高水平的消极教养时表现出相对较高水平外化问题, 经历低水平消极教养时外化问题水平相对较低。因此, 本研究中, 为揭示多巴胺系统基因与攻击行为的关联, 拟选择母亲消极教养作为环境因素, 考察其与多巴胺系统多基因对攻击行为的交互作用, 通过揭示高消极教养条件下多巴胺系统多基因与攻击行为间的关联阐明多巴胺系统基因对攻击行为的影响。

1.4 本研究问题与假设

青少年期(adolescence)是个体发展中情绪情感、认知以及神经生物功能发生重要变化的时期。青少年期PFC内基线多巴胺含量增加(Naneix et al., 2012), 脑内多巴胺受体表达(Naneix et al., 2012)以及多巴胺转运体密度(Tielbeek et al., 2018)逐渐增加并达到峰值, 因而, 青少年期多巴胺能敏感性增强, 影响多巴胺调节通路功能。青少年期多巴胺通路调节功能的改变使PFC、纹状体的结构与功能, 以及PFC与杏仁核间功能连接发生显著变化(Romeo, 2017; Toth, 2022; Tottenham & Galván, 2016), 个体表现出对奖惩、威胁性刺激等敏感性与反应性增强(Tielbeek et al., 2018)。由于青少年期多巴胺能敏感性增强, 个体所携带的与高或低多巴胺活性相关等位基因的作用可能会被进一步增强, 使多巴胺系统基因与行为间关联表现出不同于其他发展阶段的模式。

既有关于基因及其与环境交互对攻击行为影响的研究主要聚焦于幼儿或童年中晚期(Davies et al., 2015; Thibodeau et al., 2015; Vrantsidis et al., 2021), 少有研究探讨青少年期(Davies et al., 2019)。本研究将基于多基因研究视角, 以、和三个基因多态性累积分为遗传指标, 母亲消极教养为环境指标, 青少年期2次测量的攻击作为攻击行为指标, 探究多巴胺系统多基因与青少年期攻击行为的关系以及母亲消极教养的调节作用。基于已有研究, 我们拟探索多基因累积分与青少年攻击行为间的非线性关系以及母亲教养在其中的调节作用, 我们预期携带与高或低多巴胺活性相关等位基因的青少年均可能表现出高水平攻击行为, 母亲消极教养调节多基因累积分与青少年攻击行为间的关系, 母亲消极教养水平较高时多基因累积分与青少年攻击行为间的非线性关系更突出。

2 研究方法

2.1 被试

本研究被试来自一项大型追踪项目, 是利用该追踪项目被试开展的遗传研究。本研究中, 初一学年末(T1)测量母亲消极教养行为, 初二学年末(T2)收集基因数据, T1、T2两次收集青少年攻击行为数据。T1、T2为期1年的时间间隔遵循纵向研究设计常规模式, 该时间间隔能反映出有意义的发展变化或差异性, 不会因间隔过短使重复测评无意义或因间隔过长而漏评有意义的发展变化、差异性或预测效应(Collins, 2006)。此外, 在同一年(学年)类似时间重复测量, 可避免季节、开学时长、学年中不同周期性事件等因素对结果变量的影响(Dormann & Griffin, 2015)。

受研究经费所限, 该追踪项目仅对部分被试进行唾液采集和DNA分型。具有遗传数据(= 1078)与没有遗传数据(= 927)的被试在主要人口学信息上无显著差异(年龄:(2003)1独立样本t检验中, 年龄、SES、攻击行为及消极教养等方差不齐性。为校正统计偏差, 采用校正后的自由度计算t值(Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019)。此处报告自由度是校正后的自由度。= −0.74,= 0.46; SES2SES指标由父母职业、文化程度及家庭收入合成。参照既有研究(Chen et al., 2019), 父母职业根据职业的专业技术性程度归为三类:农民或下岗失业人员、蓝领、专业或半专业性人员, 分别赋值1 ~ 3。父母受教育水平包括初中(含未毕业)及以下、高中或中专(含未毕业)、大学(含专科)及以上三类, 分别赋值1 ~ 3。家庭月收入为3000元以下、3000元到6000元、6000元以上, 分别赋值1 ~ 3。参照已有研究(范兴华等, 2012), 采用因子分析法合成SES。SES得分越高, 代表家庭社会经济地位越高。:(1867) = −0.95,= 0.34; 性别: χ2= 3.39,= 1,= 0.07), 但是具有遗传数据被试的攻击行为与消极教养较低(T1攻击:(975) = 7.45,< 0.001; T2攻击:(1042) = 6.24,< 0.001; 消极教养:(1880) = 2.07,= 0.04)。具有遗传数据被试含汉族(= 1044, 96.8%)和其他民族(= 34, 3.2%)。虽然汉族与其他民族被试在基本研究变量上(性别、基因型分布、年龄、SES、T1攻击行为、T2攻击行为、母亲消极教养)无显著差异(χ2s ≤ 4.45,s ≥ 0.49; ||s ≤ 1.58,s ≥ 0.12), 但考虑到基因功能和连锁不平衡(linkage diequilibrium, LD)对适应结果的影响存在种族差异(Avinun et al., 2020), 为避免由于民族差异造成偏差并达到最大统计检验力(Cardon & Palmer, 2003), 参照已有研究(如, Avinun et al., 2020; Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022; Stocker et al., 2017), 本研究仅对汉族被试进行分析。

最终样本1044人, T1平均年龄为13.32 ± 0.49岁, 男生520人(49.8%), 女生524人(50.2%)。母亲和父亲受教育水平在初中及以下者分别占11.6%和8.3%, 高中或中专者分别占26.5%和20.6%, 大学及以上者分别占61.9%和71.1%。家庭月收入低于3000元的占23.1%, 3000 ~ 6000元的占48.0%, 高于6000元的占28.9%。

2.2 研究程序与研究工具

研究通过本单位伦理委员会审核批准。数据收集前, 将问卷施测、唾液采集流程等告知青少年所在学校、监护人及青少年本人, 取得知情同意。

青少年攻击行为数据采用问卷法, 以班级为单位集体施测, 结束后当场收回。青少年唾液样本以班级为单位组织采集。唾液样本采集严格按照规范进行, 采样时被试无发烧, 采集前30分钟无进食、吸烟、饮酒、饮水或嚼口香糖, 采集完成后检查以确保样本质量, 置于−20 ℃低温保存, 一周内冷链运输至生物公司提取分型。攻击行为问卷施测、唾液样本采集时, 每班由2名经过严格培训的发展心理学教师和研究生任主试。母亲消极教养数据由青少年将装有母亲教养问卷的信封带回家由母亲填写, 第二天带回交班主任老师统一收回。

2.2.1 多巴胺系统基因提取、分型与计分

青少年唾液样本每人不少于2 ml。利用Sequenom (San Diego, CA, USA)芯片基质辅助激光解吸/电离飞行时间(MALDI-TOF)质谱平台, 按照标准化技术规范、流程对唾液样本进行DNA提取与分型(Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022; Zhang et al., 2016)。

Val158Met (χ2= 2.06,= 0.15; Val/Val 56.8%, Val/Met 36.0%, Met/Met 7.2%)rs1799978 (χ2= 0.004,= 0.95; AA 66.5%, AG 30.1%, GG 3.4%)和rs27072 (χ2= 1.63,= 0.20; TT 5.9%, CT 33.9%, TT 60.2%)三个基因多态性的基因型分布均符合Hardy-Weinberg平衡。多基因研究基于“常见疾病−常见基因(common disease- common variant)”假设, 要求次要等位基因频率(minor allele frequency, MAF)大于5% (Manolio et al., 2009)。本研究中, 三个基因位点的次要等位基因频率均符合要求(: 25.2%,: 18.5%,: 22.9%)。三个多态性的基因型分布均不存在显著性别差异(χ2s ≤ 1.24,= 2,s ≥ 0.54)。

为确定、和三个基因是否适合线性累加, 进行系列统计检验。首先, 由于基因编码方式会影响多基因累积分结果, 为检验线性编码方式(即0, 1, 2)是否适用于形成多基因累积分, 参照已有研究(Stocker et al., 2017; 曹衍淼, 张文新, 2019), 进行线性基因模型检验。结果发现, 对T1、T2攻击, 虽然分解模型估计的参数最多, 但其解释率并未显著高于线性基因模型(即限定同一基因的显性和隐性编码估计系数相等; Δ2= 0.004、0.007,s > 0.28), 因而三个基因位点的各基因型符合线性编码方式。其次, 为了排除单个基因的主导效应, 进行等基因效应模型检验。结果显示, 等基因效应模型与线性基因效应模型间没有显著差异(Δ2= 0.002、0.007,s > 0.11), 表明三个基因对攻击行为的预测强度无差异, 不存在单个基因预测力过强主导多基因累积分的现象。因此, 根据个体携带与低多巴胺活性相关的等位基因(: Val/Val = 0, Val/Met = 1, Met/Met = 2;: AA = 0, AG = 1, GG = 2;: TT = 0, CT = 1, CC =2)的数量进行线性编码, 通过求和获得基因位点累积分。多巴胺系统多基因累积分数分布为0 (= 24, 2.3%)、1 (= 164, 15.7%)、2 (= 378, 36.2%)、3 (= 334, 32.0%)、4 (= 120, 11.5%)和5 (= 24, 2.3%)。

2.2.2 母亲消极教养行为

采用中文版儿童养育实践问卷(Child-Rearing Practices Report, CRPR; Chen et al., 2000), 由母亲报告母亲消极教养行为。该问卷在中国儿童青少年中广泛使用, 具有良好的信效度(如, Zhang et al., 2017)。在本研究中, 惩罚维度的1个条目“我告诉我的孩子, 如果他(她)做了坏事, 就要受到惩罚”与消极教养总分相关低, 参照已有研究(Zhang et al., 2017)将其删除。本研究采用拒绝(4条目, 如“如果我的孩子不来烦我, 我就不会理睬她”)、惩罚(6条目, 如“我认为体罚是管教孩子的最好的方式”)维度共10条目均分作为母亲消极教养行为指标。问卷采用5点计分(从“完全不符合” = 0到“完全符合” = 4), 得分越高表明母亲消极教养行为越多。验证性因素分析显示, 单因子模型拟合良好(χ2= 152.73,= 35, RMSEA = 0.058, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89)。本研究中母亲消极教养行为测量的Cronbach’s α系数为0.72。

2.2.3 攻击行为

采用同伴提名法测量青少年攻击行为(Crick & Grotpeter, 1995)。该量表在青少年攻击研究中广泛应用, 能够提供攻击行为有效可靠的数据(Mehari et al., 2019), 具有良好信效度。问卷包含身体攻击(如“经常打人的同学”)和关系攻击(如“谁经常在背后说别的同学的坏话”)方面的4个条目。被试按照每个题目描述的行为, 从班级中选出自己认为最符合描述的三名同学。合计每个被试得到的提名频次并进行班内标准化, 作为被试攻击行为得分。两个时间点攻击行为测量的Cronbach’s α系数分别为0.88和0.87。

2.3 数据处理与分析

首先采用相关分析考察研究变量间的关系, 其次采用SPSS 26.0进行分层线性回归分析考察多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对青少年攻击行为的影响。分层回归分析模型第一层纳入性别作为控制变量, 第二层纳入多基因累积分、母亲消极教养为预测变量, 第三层为多基因累积分与母亲消极教养的交互项, 第四层、第五层分别纳入多基因累积分二次项、其与母亲消极教养的交互项。使用包含二次项(本研究中, 为多基因累积分二次项)的回归分析能够揭示常见非线性关系, 含U型、倒U型, 以及预测变量对结果变量的预测随预测变量增大而增强或减弱的其他非线性关系模式, 二次项显著且为正则为U型关系, 二次项显著且为负则为倒U型关系(Cohen et al., 2003; Haans et al., 2016)。若任一交互项显著, 则进行简单斜率检验(Cohen et al., 2003)。简单斜率检验的做法是, 按照±1将母亲消极教养区分为高组和低组, 分析高、低母亲消极教养条件下多基因累积分、二次项与攻击行为的关联, 同时根据既有研究建议(Kochanska et al., 2011; Roisman et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015)按照±2将母亲消极教养区分为高组和低组, 以探索和阐明表现于±1之外的显著交互作用。为避免多重共线性, 多基因累积分和母亲消极教养均进行标准化处理。

为验证结果的可靠性进行系列敏感性分析:(1)对任一单基因重复上述回归模型检验, 比较单基因与多基因累积分模型显著性的差异(Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022); (2)使用MATLAB R2013b的regress和crossvalind函数, 进行k fold交叉验证(Marcot & Hanea, 2021; 张文新等, 2021); (3)将样本按照50%随机分为两个子样本进行上述回归分析, 以进行内部验证(Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022; Zhang et al., 2016)。

3 结果

3.1 描述统计结果

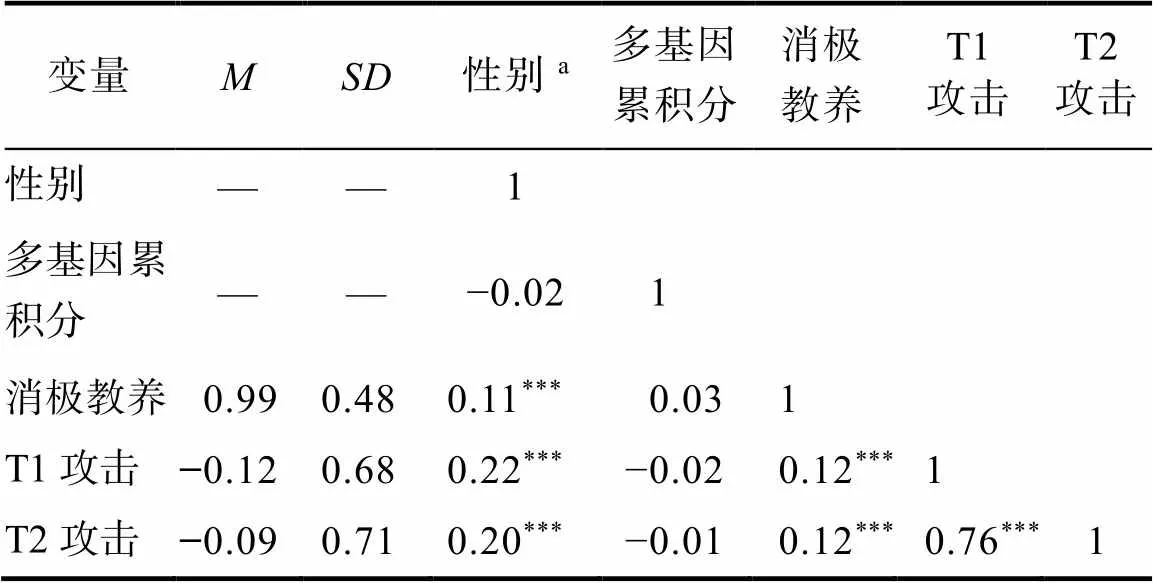

各变量描述统计与相关系数见表1。多基因累积分与母亲消极教养相关不显著, 排除了基因−环境相关。多基因累积分与两个时间点的攻击相关不显著, 母亲消极教养与两时间点的攻击行为均显著正相关。独立样本检验表明, 两个时间点的攻击行为、母亲消极教养行为性别差异显著(T1攻击3独立样本t检验中, 攻击行为、母亲消极教养的方差不齐性。为校正统计偏差, 采用校正后的自由度计算t值(Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019)。此处报告自由度是校正后的自由度:(782) = −7.13, T2攻击:(772) = −6.68, 消极教养:(958) = −3.65,s < 0.001), 男生的攻击行为和母亲消极教养行为显著高于女生。

表1 描述统计与相关系数

注:a虚拟编码, 0 = 女生, 1 = 男生。

+0.1,*< 0.05,**< 0.01,***< 0.001, 下同。

3.2 多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对青少年攻击的影响

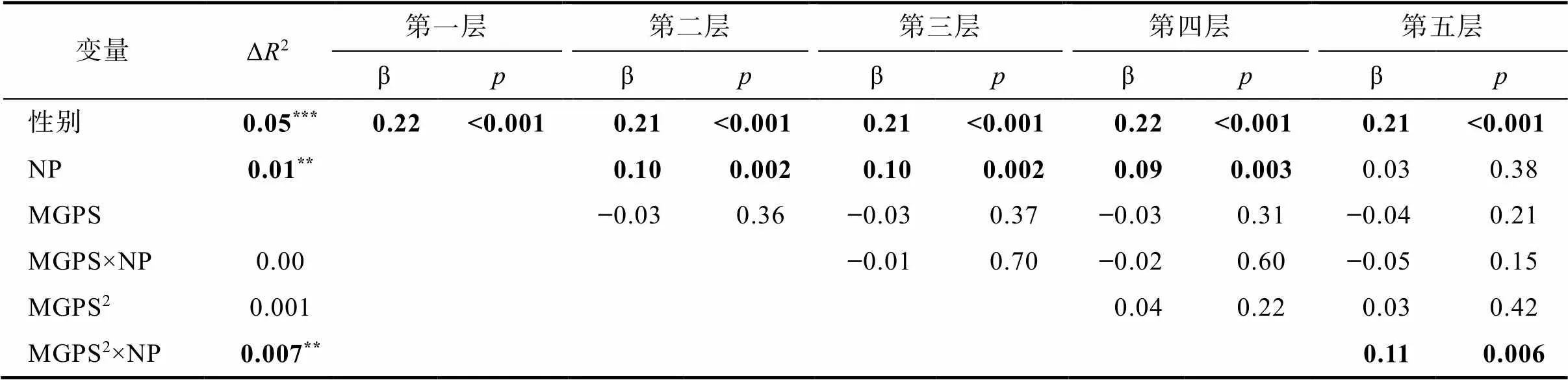

为揭示多基因与母亲消极教养对青少年攻击的影响, 分别以T1青少年攻击行为、T2青少年攻击行为为因变量, 性别为控制变量, 多基因累积分、母亲消极教养、多基因累积分×母亲消极教养交互项、多基因累积分二次项、其与母亲消极教养交互项为预测变量进行分层回归分析。

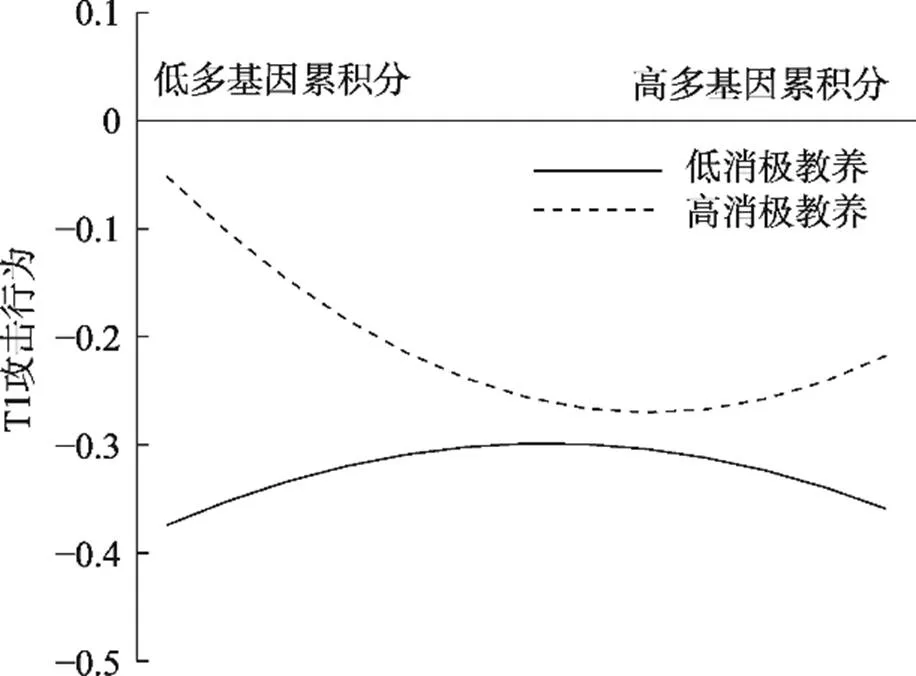

T1青少年攻击行为作为因变量的分析结果如表2所示。母亲消极教养显著正向预测T1攻击行为, 多基因累积分、其与母亲消极教养交互项对T1攻击行为的预测作用不显著, 多基因累积分二次项对T1攻击行为的预测作用不显著, 多基因累积分二次项与消极教养交互预测T1攻击行为。简单斜率分析(见图1)显示, 母亲消极教养水平较高(+1)时, 多基因累积分二次项对T1攻击行为预测显著且为正(二次项:= 0.05,= 2.75,= 0.006; 一次项:= −0.06,= −1.92,= 0.055), 多基因累积分与T1攻击行为间呈U型关系, 多基因累积分高或低的青少年均会表现出较高的攻击行为; 在母亲消极教养水平较低(−1)时, 多基因累积分二次项对T1攻击行为预测作用不显著(二次项:= −0.03,= −1.33,= 0.18; 一次项:= 0.01,= 0.17,= 0.86)。

表2 多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对T1攻击行为的影响

注:NP代表母亲消极教养行为, MGPS代表多基因累积分, 显著与边缘显著的结果均加粗显示, 下同。

图1 多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对T1攻击行为的影响

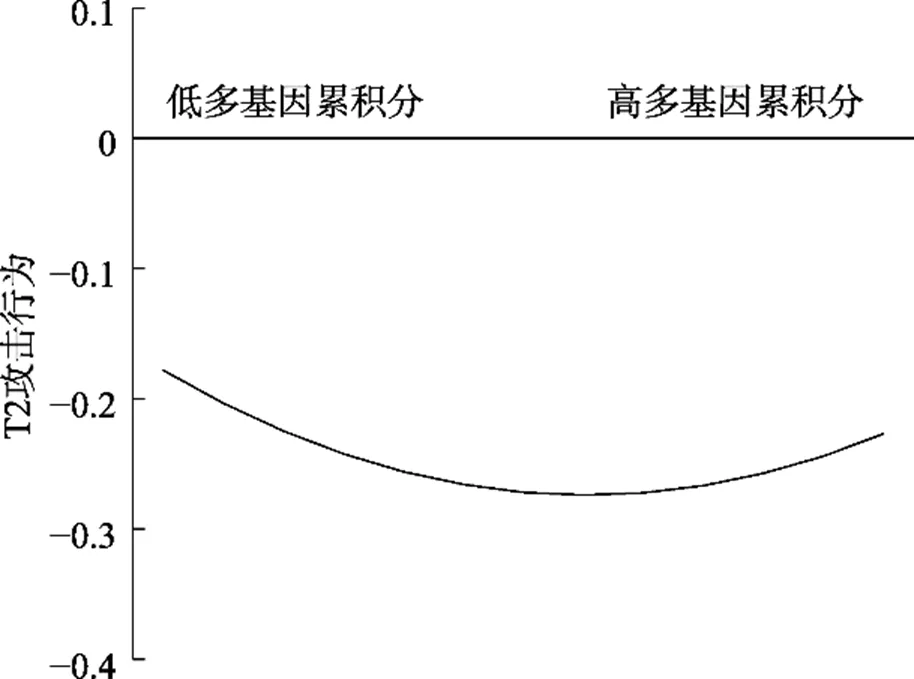

T2青少年攻击行为作为因变量的分析结果如表3所示。母亲消极教养显著正向预测T2攻击行为, 多基因累积分、其与母亲消极教养交互项对T2攻击行为的预测作用不显著。多基因累积分二次项对T2攻击行为的预测作用显著(二次项:= 0.03,= 1.98,= 0.048; 一次项:= −0.02,= −0.78,= 0.44), 多基因累积分过高或过低的青少年均表现出较高的攻击行为(见图2)。多基因累积分二次项与消极教养显著交互预测T2攻击行为。简单斜率分析显示, 母亲消极教养水平较高(+1)时, 多基因累积分二次项对T2攻击预测显著且为正(二次项:= 0.07,= 3.20,= 0.001; 一次项:= −0.04,= −1.33,= 0.18), 多基因累积分与T2攻击行为间呈U型关系, 多基因累积分过高或过低的青少年均会表现出较高的攻击行为(见图3); 母亲消极教养水平较低(−1)时, 多基因累积分二次项对T2攻击行为的预测作用不显著(二次项:= −0.02,= −0.70,= 0.49; 一次项:= −0.002,= −0.06,= 0.95)。4本研究中攻击行为得分的分布是正偏态。参照既有研究(Harden et al., 2015), 对攻击行为得分进行对数转换并重复校正前的分析。结果显示, 各统计指标显著性未发生变化, 多基因累积分、母亲消极教养及其交互项对T1、T2攻击行为的预测作用均不显著; 多基因累积分二次项对T1攻击行为的预测作用不显著, 对T2攻击行为的预测作用显著; 多基因累积分二次项与母亲消极教养显著交互预测T1、T2攻击行为。需要注意的是, 对攻击数据进行转换使得数据蕴含的原始信息发生了改变, 由此得到的回归分析结果中参数的意义解释和转换前有所改变, 反而不利于阐明变量间的关系(Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019)。基于此, 我们仍然选择在正文中报告不校正的结果。5本研究选取两个时间的攻击行为进行分析, 可能涉及发展变化问题, 为此, 我们控制T1攻击行为进行了探索性分析。结果发现, 控制T1攻击行为后, 多基因累积分、母亲消极教养及其交互项、多基因累积分二次项及其与母亲消极教养的交互项均不显著, 表明多基因累积分与母亲消极教养交互预测T1和T2时间点的攻击行为水平, 而不是T1到T2攻击行为的变化。

3.3 敏感性分析

对任一单基因、母亲消极教养对T1、T2攻击行为影响的回归分析结果显示, 任一单基因二次项(Δ2s ≤ 0.004; |s ≤ 0.03,s ≥ 0.16)、其与母亲消极教养交互项均不显著(Δ2s ≤ 0.002; |s ≤0.04,s ≥ 0.13, 见网络版附录表S1和表S2), 表明多基因累积分在提高遗传解释率和显著性方面比单基因研究更具优势。k fold交叉验证结果显示, 模型预测的攻击分数与实际攻击分数显著相关(s ≥ 0.21,s ≤ 1.46 × 10−11), 且重复10次后值仍然稳定显著(s = 0.20~0.24,s = 3.91 × 10−14~ 2.87 × 10−10, 见网络版附录“2 k fold交叉验证”)。将总样本随机分成2个子样本进行的内部验证结果显示, 在2个子样本中, 多基因累积分二次项与母亲消极教养的交互作用显著或呈显著趋势(见网络版附录表S3和表S4)。综上, 本研究的主要研究结果获得验证。

4 讨论

本研究采用多基因累积分研究范式考察了多巴胺系统多基因与青少年期两个时间点的攻击行为间的关系以及母亲消极教养在其中的调节作用。我们发现, 在较高母亲消极教养条件下多基因累积分与青少年攻击行为间呈U型关系, 多基因累积分过高或过低的青少年均会表现出较高水平攻击行为, 在经历低水平母亲消极教养时多基因累积分与青少年攻击行为的关联不显著。

表3 多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对T2攻击行为的影响

图2 多基因累积分对T2攻击行为的影响

图3 多基因累积分与母亲消极教养对T2攻击行为的影响

4.1 母亲消极教养调节多巴胺系统基因与攻击的关联

多巴胺系统基因与攻击间的U型关系在母亲消极教养水平高时更突出, 高母亲消极教养条件下, 多巴胺系统多基因累积分二次项对T1、T2攻击行为预测均显著, 携带较多或较少与低多巴胺活性相关等位基因的青少年表现出较高的攻击行为, 母亲消极教养低的环境中低多巴胺活性相关等位基因与个体的攻击行为无显著关联。这一结果与G×E交互作用理论和相关实证研究相符(Beauchaine et al., 2007; Shanahan & Hofer, 2005; Tomlinson et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2016), 表明高消极教养环境能够触发或者加剧多巴胺系统多基因与攻击行为间关联, 而相对积极环境(本研究中即低母亲消极教养环境)会阻止或减弱遗传素质的表达。

母亲消极教养促使多巴胺系统多基因与攻击行为间关联增强的机制可能表现为以下过程。母亲消极教养作为不利环境影响脑内基线多巴胺水平, 促使多巴胺系统产生诸多变化, 如DRD2受体密度降低、中脑−皮质多巴胺通路过度激活(Tielbeek et al., 2018)。由于青少年期多巴胺能敏感性以及对压力反应性增强, 此时期母亲消极教养这一不利环境因素对大脑多巴胺系统的影响更为突出。因此, 多巴胺系统多基因累积分过高或过低的青少年, 在经历高水平母亲消极教养时, PFC等脑区功能受到基因与环境的双重影响而受损, 导致攻击行为风险增加。同时, 在行为层面, 母亲消极教养使得青少年产生对攻击或敌意性的模仿、愤怒或敌意性情绪情感增强以及情绪调控能力受损等(Gershoff, 2002; Goulter et al., 2020), 这些行为方面的影响与过高或过低的多巴胺功能共同作用, 导致青少年攻击行为水平增高(Zhang et al., 2016)。

多巴胺系统多基因累积分与攻击行为关系符合U型, 与低多巴胺活性相关联的多基因累积分过高或过低的青少年均表现出较高的攻击行为。这与已有神经生化研究发现一致(如Bertolino et al., 2009; Robbins & Arnsten, 2009; Tian et al., 2013; Tunbridge et al., 2006), 过高和过低的多巴胺含量均不能有效维持皮层兴奋与抑制功能的平衡, 使PFC功能减弱, 与其他脑区的功能连接、中脑−皮质多巴胺通路与中脑−边缘多巴胺通路产生异常(Arnsten, 2009; Bertolino et al., 2009; Robbins & Arnsten, 2009; Seamans & Yang, 2004; Tian et al., 2013), 从而限制个体执行控制功能、情绪控制能力, 对奖惩的敏感性增加(Romeo, 2017), 使个体出现攻击行为(Achterberg et al., 2020; Chester & DeWall, 2016; Padmanabhan & Luna, 2014; Raine, 2008; Rosell & Siever, 2015; Sadeh et al., 2019; Tielbeek et al., 2018)。尽管这一研究结果需要未来神经生化与脑科学领域相关研究的进一步验证, 但是该结果提示, 要探究多巴胺系统基因如何影响攻击行为, 不能仅依据高低多巴胺活性判断基因“好”还是“坏”, 而是需要关注基因本身的复杂性, 考虑多巴胺系统多基因组合与攻击行为可能的U型关系。

4.2 本研究的创新、不足与展望

本研究的重要创新在于采用多基因累积法, 通过累加参与多巴胺代谢、传导和转运的多个基因位点, 揭示了多巴胺系统基因与青少年攻击行为间的非线性关系。这对于理解攻击行为的复杂生理机制具有重要启示。尽管基因−环境交互作用仅解释了不到1%的变异, 但对于发展行为遗传学研究仍具有重要意义(Evans, 1985; Hasan & Afzal, 2019)。基于基因−环境交互作用, 研究者可关注受多巴胺系统基因调控的生理机制或环境敏感性特征, 进一步揭示攻击行为产生的生理−环境机制; 在健康决策和医疗干预中, 基于个体的候选基因信息或生理机制特征、其环境敏感性, 关注不同遗传素质个体对环境(干预)的反应性差异, 从而形成更具针对性的治疗或干预方案。譬如, 为具有攻击行为且对环境更敏感的青少年提供积极教养环境, 能够在一定程度上阻止遗传素质的表达, 减少攻击行为。

本研究揭示青少年期多巴胺系统多基因对攻击行为的影响表现为非线性模式, 与以童年期儿童为被试的研究发现不同(Davies et al., 2015; Thibodeau et al., 2015; Vrantsidis et al., 2021)。这与大脑多巴胺系统的发展动态性有关(Naneix et al., 2012; Tielbeek et al., 2018; Toth, 2022), 也与青少年期个体需进行复杂决策、学习抑制不合理行为和冲动(Tielbeek et al., 2018), 且该时期大脑关键区域(如, PFC)尚未发育完全, PFC调控功能超负荷等有关(Toth, 2022)。这一结果提示, 青少年期可能是基因−环境交互作用模式发生变化的关键期。未来需采用时间跨度更长的追踪设计, 更充分地探究、比较不同年龄阶段多巴胺系统多基因与攻击行为间的关系模式, 以进一步揭示攻击遗传基因机制的发展动态性与基因作用的敏感期。同时, 本研究中, 多基因累积分二次项、其与母亲消极教养的交互项预测T1、T2的攻击行为水平, 不能预测T1到T2攻击行为的发展变化。但是, 这并不意味着基因−环境交互与攻击行为的发展无关。未来研究应深入考察遗传与环境对攻击行为及其发展变化的影响。

本研究存在一些局限。第一, 本研究基于攻击行为的神经生理机制和相关理论, 选取了参与多巴胺代谢、转运和传导的三个功能性位点, 涵盖多种影响多巴胺活性的生理过程, 避免了数据驱动和过度拟合的风险。但是, 多巴胺系统基因数量众多, 本研究未能将所有多巴胺系统基因或攻击行为候选基因涵盖在内, 因此解释率仍受限制。未来研究仍需采用多基因研究范式, 考察多巴胺系统其他候选基因或多巴胺系统与其他系统基因间的联合效应, 以更全面地揭示攻击行为的多基因遗传基础。第二, 虽然本研究进行了多种内部重复验证, 为研究结果的可靠性提供了证据。但随机分组后样本量减少可能会降低统计检验力; 本研究未有使用相同测量工具及相似特征被试的外部样本, 无法进行外部验证。未来尚需在其他样本, 尤其是更大样本中进行外部验证。第三, 本研究只关注了城市常态群体的青少年, 研究结果可能不适用于高风险青少年群体, 如低社会经济地位或临床样本。由于高风险群体中母亲消极教养水平可能更高、存在攻击之外的共病现象等(Davies et al., 2019; Gard et al., 2022; Stocker et al., 2017), 基因与攻击行为的关联强度与模式可能不同于常态青少年群体。第四, 本研究仅考察了母亲消极教养, 未涉及父亲教养。父亲教养行为对青少年问题行为具有重要影响(如, Cao & Rijlaarsdam, 2022)。未来研究可同时关注父亲教养和母亲教养行为, 以更全面揭示父母教养行为对青少年攻击行为的影响作用。第五, 本研究仅关注青少年的基因, 但是考虑父母基因可能与教养行为存在关联以及父母与孩子间的代际传递问题, 未来有必要也测评父母的基因, 以更全面探究基因与环境对青少年攻击行为的影响。

5 结论

本研究为攻击行为的多基因遗传基础以及多巴胺系统基因与青少年攻击行为间存在非线性关系提供了证据。在青少年早中期, 多巴胺系统基因与攻击行为呈非线性关系, 并且高消极教养环境能够加剧或放大二者之间的关系。这一结果提示, 攻击行为干预需要从减少消极教养、增加积极教养入手。

Achterberg, M., van Duijvenvoorde, A. C., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Crone, E. A. (2020). Longitudinal changes in DLPFC activation during childhood are related to decreased aggression following social rejection.(15), 8602−8610.

Albaugh, M. D., Harder, V. S., Althoff, R. R., Rettew, D. C., Ehli, E. A., Lengyel-Nelson, T., ... Hudziak, J. J. (2010). COMT Val158Met genotype as a risk factor for problem behaviors in youth.,(8), 841−849.

Ansary, N. S., McMahon, T. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2017). Trajectories of emotional-behavioral difficulty and academic competence: A 6-year, person-centered, prospective study of affluent suburban adolescents.,(1), 215−234.

Arnsten, A. F. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function.,(6), 410−422.

Avinun, R., Nevo, A., Radtke, S. R., Brigidi, B. D., & Hariri, A. R. (2020). Divergence of an association between depressive symptoms and a dopamine polygenic score in Caucasians and Asians.0(2), 229−235.

Beauchaine, T. P., Gatzke-Kopp, L. M., & Mead, H. K. (2007). Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence.,(2), 174−184.

Bertolino, A., Fazio, L., Di Giorgio, A., Blasi, G., Romano, R., Taurisano, P., ... Sadee, W. (2009). Genetically determined interaction between the dopamine transporter and the D2 receptor on prefronto-striatal activity and volume in humans.,(4), 1224−1234.

Cao, C., & Rijlaarsdam, J. (2022). Childhood parenting and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms: Moderation by multilocus hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-related genetic variation., Advanced online publication.

Cao, Y, M., & Zhang, W. X. (2019). The influence of dopaminergic genetic variants and maternal parenting on adolescent depressive symptoms: A multilocus genetic study.,, 1102−1115.

[曹衍淼, 张文新. (2019). 多巴胺系统基因与母亲教养行为对青少年抑郁的影响: 一项多基因研究.,, 1102−1115.]

Cardon, L. R., & Palmer, L. J. (2003). Population stratification and spurious allelic association.(9357), 598−604.

Chen, J., Lipska, B. K., Halim, N., Ma, Q. D., Matsumoto, M., Melhem, S., ... Weinberger, D. R. (2004). Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): Effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain.(5), 807−821.

Chen, L., Zhang, W., Ji, L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2019). Developmental trajectories of Chinese adolescents’ relational aggression: Associations with changes in social-psychological adjustment.(6), 2153−2170.

Chen, X., Liu, M., Li, B., Cen, G., Chen, H., & Wang, L. (2000). Maternal authoritative and authoritarian attitudes and mother-child interactions and relationships in urban China.(1), 119−126.

Chester, D. S., & DeWall, C. N. (2016). The pleasure of revenge: Retaliatory aggression arises from a neural imbalancetoward reward.(7), 1173−1182.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003).(3rd ed). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Collins, L. M. (2006). Analysis of longitudinal data: The Integration of Theoretical Model, Temporal Design, and Statistical Model., 505−528.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment.,(3), 710−722.

Davies, P., Cicchetti, D., & Hentges, R. F. (2015). Maternal unresponsiveness and child disruptive problems: The interplay of uninhibited temperament and dopamine transporter genes.,(1), 63−79.

Davies, P. T., Pearson, J. K., Cicchetti, D., Martin, M. J., & Cummings, E. M. (2019). Emotional insecurity as a mediator of the moderating role of dopamine genes in the association between interparental conflict and youth externalizing problems.,(3), 1111−1126.

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies.(4), 489−505.

Estévez, E., Jiménez, T. I., & Moreno, D. (2018). Aggressive behavior in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family, and school adjustment problems.(1), 66−73.

Evans, M. G. (1985). A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis.,(3), 305−323.

Fan, X. H., Fang, X. Y., Liu, Y., Lin, X. Y., & Yuan, X. J. (2012). The effect of social support and social identity on the relationship between perceived discrimination and socio-cultural adjustment among Chinese migrant children.(5), 647−663.

[范兴华, 方晓义, 刘杨, 蔺秀云, 袁晓娇. (2012). 流动儿童歧视知觉与社会文化适应: 社会支持和社会认同的作用.(5), 647−663.]

Ganiban, J. M., Liu, C., Zappaterra, L., An, S., Natsuaki, M. N., Neiderhiser, J. M., ... Leve, L. D. (2021). Gene × environment interactions in the development of preschool effortful control, and its implications for childhood externalizing behavior.,(5), 448−462.

Gard, A. M., Hein, T. C., Mitchell, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., McLanahan, S. S., Monk, C. S., & Hyde, L. W. (2022). Prospective longitudinal associations between harsh parenting and corticolimbic function during adolescence.,(3), 981−996.

Gatzke-Kopp, L. M. (2011). The canary in the coalmine: The sensitivity of mesolimbic dopamine to environmental adversity during development.(3), 794−803.

Genis-Mendoza, A. D., López-Narvaez, M. L., Tovilla-Zárate, C. A., Sarmiento, E., Chavez, A., Martinez-Magaña, J. J., ... Nicolini, H. (2018). Association between polymorphisms of the DRD2 and ANKK1 genes and suicide attempt: A preliminary case-control study in a Mexican population.(4), 193−198.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review.,(4), 539−579.

Goulter, N., McMahon, R. J., Pasalich, D. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2020). Indirect effects of early parenting on adult antisocial outcomes via adolescent conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits.(6), 930−942.

Haans, R. F., Pieters, C., & He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U- and inverted U- shaped relationships in strategy research.(7), 1177−1195.

Harden, K. P., Patterson, M. W., Briley, D. A., Engelhardt, L. E., Kretsch, N., Mann, F. D., ... Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2015). Developmental changes in genetic and environmental influences on rule-breaking and aggression: Age and pubertal development.(12), 1370−1379.

Hasan, A., & Afzal, M. (2019). Gene and environment interplay in cognition: Evidence from twin and molecular studies, future directions and suggestions for effective candidate gene × environment (cG×E) research.,, 121−130.

Hygen, B. W., Belsky, J., Stenseng, F., Lydersen, S., Guzey, I. C., & Wichstrøm, L. (2015). Child exposure to serious life events, COMT, and aggression: Testing differential susceptibility theory.(8), 1098−1104.

Jones, G., Zammit, S., Norton, N., Hamshere, M. L., Jones, S. J., Milham, C., ... Owen, M. J. (2001). Aggressive behaviour in patients with schizophrenia is associated with catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype.,(4), 351−355.

Kochanska, G., Kim, S., Barry, R. A., & Philibert, R. A. (2011). Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility?(2), 605−616.

Lotta, T., Vidgren, J., Tilgmann, C., Ulmanen, I., Melén, K., Julkunen, I., & Taskinen, J. (1995). Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: A revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme.,(13), 4202−4210.

Manolio, T. A., Collins, F. S., Cox, N. J., Goldstein, D. B., Hindorff, L. A., Hunter, D. J., ... Visscher, P. M. (2009). Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases.,(7265), 747−753.

Marcot, B. G., & Hanea, A. M. (2021). What is an optimal value of k in k-fold cross-validation in discrete Bayesian network analysis?(3), 2009−2031.

Mehari, K. R., Waasdorp, T. E., & Leff, S. S. (2019). Measuring relational and overt aggression by peer report: A comparison of peer nominations and peer ratings.(3), 362−374.

Meyer, B. M., Huemer, J., Rabl, U., Boubela, R. N., Kalcher, K., Berger, A., ... Pezawas, L. (2016). Oppositional COMT Val158Met effects on resting state functional connectivity in adolescents and adults.(1), 103−114.

Naneix, F., Marchand, A. R., Di Scala, G., Pape, J. R., & Coutureau, E. (2012). Parallel maturation of goal-directed behavior and dopaminergic systems during adolescence.(46), 16223−16232.

Nikolova, Y. S., Ferrell, R. E., Manuck, S. B., & Hariri, A. R. (2011). Multilocus genetic profile for dopamine signaling predicts ventral striatum reactivity.,(9), 1940−1947.

Padmanabhan, A., & Luna, B. (2014). Developmental imaging genetics: Linking dopamine function to adolescent behavior., 27−38.

Pinsonneault, J. K., Han, D. D., Burdick, K. E., Kataki, M., Bertolino, A., Malhotra, A. K., ... Sadee, W. (2011). Dopamine transporter gene variant affecting expression in human brain is associated with bipolar disorder.(8), 1644−1655.

Raine, A. (2008). From genes to brain to antisocial behavior.,(5), 323−328.

Robbins, T. W., & Arnsten, A. F. (2009). The neuropsychopharmacology of fronto-executive function: Monoaminergic modulation.,, 267−287.

Roisman, G. I., Newman, D. A., Fraley, R. C., Haltigan, J. D., Groh, A. M., & Haydon, K. C. (2012). Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis-stress: Recommendations for evaluating interaction effects.(2), 389−409.

Romeo, R. D. (2017). The impact of stress on the structure of the adolescent brain: Implications for adolescent mental health.(Pt B), 185−191.

Rosell, D. R., & Siever, L. J. (2015). The neurobiology of aggression and violence.,(3), 254−279.

Sadeh, N., Spielberg, J. M., Logue, M. W., Hayes, J. P., Wolf, E. J., McGlinchey, R. E., ... Miller, M. W. (2019). Linking genes, circuits, and behavior: Network connectivity as a novel endophenotype of externalizing.,(11), 1905−1913.

Seamans, J. K., & Yang, C. R. (2004). The principal features and mechanisms of dopamine modulation in the prefrontal cortex.,(1), 1−58.

Shanahan, M. J., & Hofer, S. M. (2005). Social context in gene-environment interactions: Retrospect and prospect.,(1), 65−76.

Stocker, C. M., Masarik, A. S., Widaman, K. F., Reeb, B. T., Boardman, J. D., Smolen, A., ... Conger, K. J. (2017). Parenting and adolescents’ psychological adjustment: Longitudinal moderation by adolescents’ genetic sensitivity.(4), 1289−1304.

, B. G., &, L. S. ().(7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Thibodeau, E. L., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2015). Child maltreatment, impulsivity, and antisocial behavior in African-American children: Moderation effects from a cumulative dopaminergic gene index.,(4 Pt 2), 1621−1636.

Tian, T., Qin, W., Liu, B., Jiang, T., & Yu, C. (2013). Functional connectivity in healthy subjects is nonlinearly modulated by the COMT and DRD2 polymorphisms in a functional system-dependent manner.(44), 17519−17526.

Tielbeek, J. J., Al-Itejawi, Z., Zijlmans, J., Polderman, T. J., Buckholtz, J. W., & Popma, A. (2018). The impact of chronic stress during adolescence on the development of aggressive behavior: A systematic review on the role of the dopaminergic system in rodents., 187−197.

Tomlinson, R. C., Hyde, L. W., Dotterer, H. L., Klump, K. L., & Burt, S. A. (2022). Parenting moderates the etiology of callous-unemotional traits in middle childhood.,(8), 912−920.

Toth, B. (2022). Differential dopamine dynamics in adolescents and adults.(14), 2853−2855.

Tottenham, N., & Galván, A. (2016). Stress and the adolescent brain: Amygdala-prefrontal cortex circuitry and ventral striatum as developmental targets., 217−227.

Tunbridge, E. M., Harrison, P. J., & Weinberger, D. R. (2006). Catechol-O-methyltransferase, cognition, and psychosis: Val158Met and beyond.,(2), 141−151.

van Goozen, S. H. M., Langley, K., Northover, C., Hubble, K., Rubia, K., Schepman, K., ... Thapar, A. (2016). Identifying mechanisms that underlie links between COMT genotype and aggression in male adolescents with ADHD.,(4), 472−480.

Vrantsidis, D. M., Clark, C. A., Volk, A., Wakschlag, L. S., Espy, K. A., & Wiebe, S. A. (2021). Exploring the interplay of dopaminergic genotype and parental behavior in relation to executive function in early childhood., Advanced online publication.

Wang, F. M., Chen, J. Q., Xiao, W. Q., Ma, Y. T., & Zhang, M. (2012). Peer physical aggression and its association with aggressive beliefs, empathy, self-control, and cooperation skills among students in a rural town of China.,(16), 3252−3267.

Xing, Q., Qian, X., Li, H., Wong, S., Wu, S., Feng, G., ... He, L. (2007). The relationship between the therapeutic response to risperidone and the dopamine D2 receptor polymorphism in Chinese schizophrenia patients.(5), 631−637.

Yamaguchi, T., & Lin, D. (2018). Functions of medial hypothalamic and mesolimbic dopamine circuitries in aggression., 104−112.

Yu, C., Zhang, J., Zuo, X., Lian, Q., Tu, X., & Lou, C. (2021). Correlations of impulsivity and aggressive behaviours among adolescents in Shanghai, China using bioecological model: Cross-sectional data from Global Early Adolescent Study.(7), e043785.

Zai, C. C., Ehtesham, S., Choi, E., Nowrouzi, B., de Luca, V., Stankovich, L., ... Beitchman, J. H. (2012). Dopaminergic system genes in childhood aggression: Possible role for DRD2.,(1), 65−74.

Zhang, J. P., & Malhotra, A. K. (2011). Pharmacogenetics and antipsychotics: Therapeutic efficacy and side effects prediction.,(1), 9−37.

Zhang, W., Cao, C., Wang, M., Ji, L., & Cao, Y. (2016). Monoamine oxidase a (MAOA) and catechol-O- methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphisms interact with maternal parenting in association with adolescent reactive aggression but not proactive aggression: Evidence of differential susceptibility., 812−829.

Zhang, W., Cao, Y., Wang, M., Ji, L., Chen, L., & Deater- Deckard, K. (2015). The dopamine D2 receptor polymorphism (DRD2 TaqIA) interacts with maternal parenting in predicting early adolescent depressive symptoms: Evidence of differential susceptibility and age differences.(7), 1428−1440.

Zhang, W. X., Li, X., Chen, G. H., & Cao, Y. M. (2021). The relationship between positive parenting and adolescent prosocial behaviour: The mediating role of empathy and the moderating role of the oxytocin receptor gene.,(9), 976−991.

[张文新, 李曦, 陈光辉, 曹衍淼. (2021). 母亲积极教养与青少年亲社会行为: 共情的中介作用与OXTR基因的调节作用.(9), 976−991.]

Zhang, W. X., Wei, X., Ji, L. Q., Chen, L., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2017). Reconsidering parenting in Chinese culture: Subtypes, stability, and change of maternal parenting style during early adolescence.(5)1117−1136.

The U-shaped relationship between dopaminergic genes and adolescent aggressive behavior: The moderating role of maternal negative parenting

LIN Xiaonan, CAO Yanmiao, ZHANG Wenxin, JI Linqin

(School of Psychology, Shandong Normal University, Shandong Provincial Institute of Student Development and Mental Health, Jinan 250014, China)

Dopaminergic genes have been frequently found to be associated with aggressive behavior, but the results are inconsistent. One reason for the inconsistencies is there might be the U-shaped relationship between dopaminergic genetic variants and aggressive behavior. More specifically, evidence has suggested an inverted U-shaped relationship between dopamine activity and prefrontal cortex (PFC) function (a critical region related to aggression), with both dopaminergic hypofunction and hyperfunction, were related to poor PFC function. It is possible that the relationship between dopaminergic genes and aggression approximates a U-shaped function. However, such U-shaped relationship is rarely investigated in previous studies. Moreover, several concerns have been raised about the ignoring the polygenic traits of aggressive behavior when conducting gene by environment interaction (G×E) research using single loci. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the interaction between dopaminergic genetic variants and maternal negative parenting on adolescent aggressive behavior by adopting the approach of multilocus genetic profile score (MGPS).

Participants were 1044 adolescents (mean age 13.32 ± 0.49 years old at Time 1, 50.2% females) recruited from the community. The adolescents completed two assessments with an interval of one year. Saliva samples, mother-reported parenting data and data on peer-nominated aggressive behavior were collected. All measures showed good reliability. The MGPS was created byrs4680 polymorphisms,rs1799978 polymorphisms andrs27072 polymorphisms. Genotyping in three dopaminergic genes were performed for each participant in real time with MassARRAY RT software version 3.0.0.4 and analyzed using the MassARRAY Typer software version 3.4 (Sequenom). To examine whether negative parenting moderates the effects of MGPS on adolescent aggressive behavior, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted.

The results found that after controlling for gender, maternal negative parenting was a significant risk factor for adolescent aggressive behavior, with higher negative parenting related to more aggressive behavior. The main effect of the quadratic term of MGPS on adolescents’ aggressive behavior was significant at Time 2, indicating a U-shaped relationship between MGPS and adolescent aggressive behavior. Moreover, the quadratic term of MGPS significantly interacted with maternal negative parenting in predicting aggressive behavior at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively. Specifically, there was a U-shaped relationship between MGPS and adolescent aggressive behavior, indicating that adolescents with higher and lower MGPS exhibited higher levels of aggressive behavior when experiencing higher levels of maternal negative parenting. No significant effect of MGPS on adolescent aggressive behavior when experiencing lower levels of maternal negative parenting existed.

This study provides evidence for the molecular mechanisms of multilocus genetic profile scores and gene-environment interactions in adolescent aggressive behavior.

aggressive behavior, maternal negative parenting, dopamine, multilocus genetic profile score, U-shaped relationship

B844; B845

2022-03-17

* 国家自然科学基金项目(32071073, 31900776, 31971008), 山东省自然科学基金项目(ZR2019MC025)。

纪林芹, E-mail: sdjlq@126.com