论共同但有区别的责任原则在海洋塑料污染国际立法中的适用性

周晟全 施余兵

一、问题的提出

联合国环境大会(United Nations Environment Assembly)在2022 年3 月2日的第5/14 号决议“结束塑料污染:制定具有法律约束力的国际文书”中要求联合国环境规划署(United Nations Environment Programme,以下简称“UNEP”)召集政府间谈判委员会,并于2022 年下半年开始工作,争取在2024 年底完成相关工作。1参见United Nations Environment Programme, Scenario note for the first session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UNEP website (27 Nov 2022), https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/4131 3/Scenario_note_E.pdf.UNEP 旨在制定一项具有法律约束力的塑料污染(包括海洋环境中的塑料污染)国际文书的政府间谈判委员会(Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, 以下简称“INC”)第一届、第二届会议(以下简称“INC-1”“INC-2”)已分别于2022 年11 月28 日至12 月2 日、2023 年5 月29 日至6 月2 日在乌拉圭埃斯特角城会议展览中心、法国巴黎联合国教科文组织总部举行。

在INC-1及INC-2的会议进程中,包括中国、阿根廷、拉丁美洲和加勒比地区、2参见International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 28 November 2022, ISSD website (10 Dec 2022), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marineenvironment-negotiating-committee-inc1-daily-report-28nov2022.南非、塞内加尔、3参见International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 30 November 2022, ISSD website (10 Dec 2022), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marineenvironment-negotiating-committee-inc1-daily-report-30nov2022.印度、菲律宾4参见International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 31 May 2023,ISSD website (7 Jun 2023), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environmentnegotiating-committee-inc2-daily-report-31may2023;及第二联络小组5参见International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 1 June 2023,ISSD website (7 Jun 2023), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environmentnegotiating-committee-inc2-daily-report-1jun2023;在内的多个国家、地区代表团及联络小组在一般性发言和文书结构的范围、目标以及备选方案环节中提出,应考虑共同但有区别的责任原则(以下简称“CBDR 原则”),这些提案体现了部分参加政府间谈判国家的政治意愿,应引起国际社会的重视。然而,一个无法回避的事实是,CBDR 原则迄今仅明确适用于气候变化领域,在塑料污染领域,特别是海洋塑料污染领域是否适用该原则仍然存在争议,需要进行更深层次的探讨。为了解决这一问题,本文将首先讨论CBDR 原则的源起与意涵,并总结CBDR 原则在气候变化领域外的反映与体现,随后将就CBDR 原则在海洋塑料污染领域的适用性进行分析,并就未来塑料污染国际文书纳入CBDR 原则时的具体方式进行展望。

二、CBDR 原则的源起与意涵

CBDR 原则经历了长期的发展与内涵演变,最终成为气候变化领域的基本原则。本部分所涉及的源起,即指在气候变化领域中CBDR 原则的演进;而意涵,则指CBDR 原则所映射的本质内容,即“共同利益”与“实质公平”。6参见季华:《“共同但有区别责任”与气候变化国际法律机制》,中国政法大学出版社2022 年版,第64-72 页。

(一)CBDR 原则的源起

CBDR 原则的演进,可分为初步形成、具体确立和进一步发展三个阶段。

1.CBDR 原则的初步形成

学界一般认为,CBDR 原则在国际环境法诞生之后才初步形成。1972 年斯德哥尔摩人类环境会议以及《联合国人类环境会议宣言》(以下简称“《人类环境宣言》”)的通过标志着国际环境法的诞生。7参见林灿铃等著:《国际环境法的产生与发展》,人民法院出版社2006 年版,第50 页。该宣言首次含蓄地提出了环境领域的共同责任和区别责任的内容。例如,《人类环境宣言》提出,“保护和改善人类环境是关系到全世界各国人民的幸福和经济发展的重要问题,也是全世界各国人民的迫切希望和各国政府的责任。”8《联合国人类环境会议宣言》第一部分第2 条。“所有国家的环境政策应该提高,而不应该损及发展中国家现有或将来的发展潜力。……”9《联合国人类环境会议宣言》第二部分第11 条。尽管这种表述相当审慎,仍然说明“共同责任”与“区别责任”的概念在当时已经出现。但CBDR 原则并没有在当时确立,而仅处在“初步形成”的阶段,主要原因在于,在人类环境会议举行时,作为后续CBDR 原则主要支持者的发展中国家,其关注重心并不在全球环境合作,而更注重于国际经济新秩序的形成,因此,CBDR 原则的形成条件在当时并不成熟。10参见寇丽:《共同但有区别责任原则:演进、属性与功能》,载《法律科学(西北政法大学学报)》2013 年第4 期,第95-103 页。

2.CBDR 原则的确立

1992 年5 月9 日通过并于同年6 月在联合国环境与发展会议上开放签署的《联合国气候变化框架公约》(以下简称“UNFCCC”),以及前述会议通过的《关于环境与发展的里约宣言》(以下简称“《里约宣言》”),均对CBDR 原则进行明确规定。UNFCCC 在序言中提到,“……承认气候变化的全球性,要求所有国家根据其共同但有区别的责任和各自的能力及其社会和经济条件,尽可能开展最广泛的合作,并参与有效和适当的国际应对行动……”11《联合国气候变化框架公约》序言。;《里约宣言》则指出,“……鉴于导致全球环境退化的各种不同因素,各国负有共同的但是又有差别的责任……”。12《关于环境与发展的里约宣言》原则7。

同时,《里约宣言》中提到,“……发达国家承认,鉴于他们的社会给全球环境带来的压力,以及他们所掌握的技术和财力资源,他们在追求可持续发展的国际努力中负有责任。”13同上注。这一规定明确指出,发达国家在气候变化领域中负有历史责任,也认可发达国家和发展中国家当下的国情区别,其所体现的“历史责任”“国家能力”两大要素,被视为CBDR 原则适用的前提条件。

简而言之,UNFCCC 和《里约宣言》的规定均体现了二十世纪九十年代的国际社会对气候变化问题的理解和态度,各国对CBDR 原则的认识也得到了进一步深化,试图寻求气候变化领域的“实质公平”。但遗憾的是,二者的规定均未在明确CBDR 原则的基础上作出更为细致且具体的规定,CBDR 原则的具体应用仍然存在发展的空间。

3.CBDR 原则的进一步发展

1997 年UNFCCC 第三次缔约国会议通过的《京都议定书》对CBDR 原则作出了具体化的规定。概而言之,《京都议定书》明确了发达国家的温室气体减排任务,却并未对发展中国家规定强制减排义务。《京都议定书》所采取的“二分法”是严格适用CBDR 原则的体现,正因如此,发达国家与发展中国家之间就CBDR原则的适用与否产生了极大的分歧,争论相较此前更加激烈。

2015 年通过的《巴黎协定》为 2020 年后全球合作应对气候变化指明了方向和目标,是公认的全面平衡、持久有效、具有法律约束力的气候变化国际协议。14参见朱松丽,高翔:《从哥本哈根到巴黎——国际气候制度的变迁和发展》,清华大学出版社2017 年版,第247 页。CBDR 原则在《巴黎协定》中多次被明确提及,但其内涵却发生了一定的改变,形成了“共区责任+各自能力+不同国情”的要件形态:15参见周琛:《论碳中和愿景下的共同但有区别责任原则》,载《武汉大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》2023 年第2 期,第152-163 页。由《京都议定书》通过“二分法”规定的发达国家强制减排、发展中国家自愿参与减排的温室气体减排模式,改为通过“国家自主贡献”进行减排的新模式,将所有缔约方都纳入温室气体减排所涵盖的范围内。16《巴黎协定》第4 条。《巴黎协定》之后,UNFCCC 第二十六次缔约国会议通过的《格拉斯哥气候公约》中仍然对CBDR 原则采坚持的态度,并对《巴黎协定》中涉及CBDR 原则的规定进行了回顾与重申。17参见United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Glasgow Climate Pact,UNFCCC website (15 Dec 2022), https://unfccc.int/documents/310475.

(二)CBDR 原则的意涵

从前文所述不难看出,CBDR 原则本身是在不断发展、变化的。有学者认为,经历了多年的发展,CBDR 原则的内涵已经发生了重大变化,在其“共同责任”和“有区别的责任”两个要素中,后者的内涵发生了较大的变化。18参见SHI Yubing, Climate Change and International Shipping: The Regulatory Framework for the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Brill Nijhoff, 2017, p. 86-89.然而,笔者认为,CBDR 原则的意涵并未发生太大的变化。从CBDR 原则的名称可以看出,该原则包含两方面内容——共同责任与区别责任,这两方面内容直接体现了CBDR 原则的意涵,即“共同利益”与“实质公平”。19同前注6,季华。

1.共同责任所体现的共同利益

如前文所述,“共同责任”这一概念最早体现于《人类环境宣言》中,并在UNFCCC、《京都议定书》等后续文书中得到进一步的确认。各国应当在环境领域与气候变化领域承担共同责任的主要原因在于,地球生态系统是一个整体,整体中的任一要素遭受破坏,都必将对整体产生影响,而人类的共同利益又与作为整体的地球生态系统之间存在直接联系。因此,环境领域与气候变化领域的议题,对人类的影响是在人类的共同利益层面出现的,也正因如此,针对这些议题,需要所有国家承担共同责任。

2.区别责任所体现的实质公平

为了探求实质上的公平,CBDR 原则引入了“区别责任”。正如《里约宣言》原则7 所述,这种区别责任的来源有两方面,既基于国家的历史责任,也基于当下的国家能力,前文提到,这两大要素,也被视作适用CBDR 的前提条件。20同前注12,《关于环境与发展的里约宣言》。自工业革命以来,老牌的工业化发达国家的发展对地球生态环境产生了前所未有的破坏,这些破坏也是导致当下环境现状的主要原因。发达国家认识到其国内环境受到破坏后,开始尝试将高污染、高排放的工业建立在其国家范围之外,从而将污染与排放转移至发展中国家;同时,发达国家的人口相比于全球人口,虽然所占基数较小,却是造成目前的全球环境污染的“主要推手”。基于污染者付费原则(Polluter-pays Principle),发达国家应当承担历史上的环境破坏责任。而发展中国家受限于目前的国家能力,承担发达国家转移的污染与排放后,在环境治理上能够发挥的能力十分有限,难以通过自身的能力充分表达国家自身的意愿;且发展中国家中不乏人口大国,为保障其人民生活,需要进一步发展工业以促进经济发展。因此,为了在发展中国家和发达国家之间达成实质上的公平,需要发展中国家和发达国家承担区别责任。

考虑到发展中国家的能力和国情问题,《巴黎协定》认可发展中国家在落实温室气体减排时所面临的困境,对发展中国家作出相对较为“宽松”的规定,换言之,《巴黎协定》为“有区别的责任”提供了落实可能。除引入前文所述的国家自主贡献外,《巴黎协定》还对包括资金援助、技术转让和能力建设等内容进行了相对细致的规定,其中着重为加强能力建设规定了具体落实措施。21《巴黎协定》第11 条。

三、CBDR 原则在气候变化领域外的反映与体现

尽管CBDR 原则起源并发展于气候变化领域,但在气候变化领域外的其他领域,也存在一些条约和判例实践能够反映、体现CBDR 原则。

(一)《生物多样性公约》

自1988 年英国生态学家诺曼·迈尔斯确定了植物特有程度高、栖息地丧失严重的热带雨林“热点”(Hotspots)后,22参见Norman Myers, Threatened biotas: “Hot spots” in tropical forests, Environmentalist,Vol. 8:3, p. 187-208 (1988).多个政府间组织经过多年工作,至2016 年,共认定了36 个“生物多样性热点”,这些地区被视作地球上生物最丰富但仍受到威胁的地区。23参见Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Biodiversity Hotspots Defined, CEPF website (15 Dec 2022), https://www. cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/hotspots-defined.

图1 生物多样性热点全球分布图24图1 系Kellee Koenig 制作的生物多样性热点全球分布图,下载自https://zenodo.org/record/4311850#.Y66f FfVBze9。

从生物多样性热点的全球分布可以看出,目前绝大多数的生物多样性存在于东南亚、非洲以及南美洲的发展中国家。但考虑到国家能力问题,发展中国家并不能较好地对生物多样性进行保护;同时,在对生物多样性加以利用的领域,例如生物技术等,发展中国家直至进入21 世纪后才在相关领域具有显著发展。25参见The World Academy of Science, Biotechnology: A growing field in the developing world, TWAS website (15 Dec 2022), https://twas.org/article/biotechnology-growing-fielddeveloping-world.此前,对生物多样性的利用多数是在发达国家进行,而发达国家的生物多样性从目前来看已经损失极大。因此,发达国家由于其历史责任,对资助发展中国家保护生物多样性负有责任,同样负有与发展中国家共享其利用生物多样性所获利益的责任。

尽管CBDR 原则并没有在《生物多样性公约》(以下简称“CBD”)中明确被提及,但CBD 的文本中仍含蓄地反映和体现了CBDR 原则。例如,CBD 序言中提到,“确认生物多样性的保护是全人类的共同关切事项”、第20 条第2款提到,“发达国家缔约国应提供新的额外的资金,以使发展中国家缔约国能支付它们因执行那些履行本公约义务的措施而承负的一定的全部增加费用,并使它们能享受到本公约条款产生的惠益。”26《生物多样性公约》序言、第20 条第2 款。同时,CBD 第15、16、19 条关于遗传资源取得、技术的取得与转让、生物技术的处理与分配等规定,实际上都体现了发达国家与发展中国家在责任承担上的“区别化”。有学者提出,包括CBDR 原则在内的“里约原则”必须成为CBD 框架的支柱,并指出发达国家在生物多样性丧失问题上应承担历史责任。27参见Viviana Muñoz Tellez, Proposals to Advance the Negotiations of the Post 2020 Biodiversity Framework, the South Centre website, (15 Dec 2022), https://www.southcentre.int/policybrief-90-march-2021/.

(二)《关税与贸易总协定》

世界贸易组织的许多协定中都对发展中国家提供了诸如特殊优惠、技术援助、分阶段实施等更加宽松的义务。28参见Joost Pauwelyn, The End of Differential Treatment for Developing Countries? Lessons from the Trade and Climate Change Regimes, Review of European Community &International Environmental Law, Vol. 22:1, p. 29-41 (2013).可以说,在贸易机制领域,世界贸易组织承认发展中国家与发达国家的国家能力差异和发展需要的差异,并相应地赋予双方“区别化”的义务。有学者提出,发达国家应承担“相当大部分成本的道德责任”。29参见Robyn Eckersley, Understanding the interplay between the climate and trade regimes,Climate and Trade Polici es in a Post-2012 World, United Nations Environment Programme,2009, p. 11-18.原因在于,在贸易领域,发达国家曾经或已经获得了相当大的收益,而发展中国家则面临更加高昂的贸易活动实施成本,这种成本的出现,部分原因在于发达国家曾经对发展中国家的殖民化等行为,换言之,发达国家对发展中国家高昂的贸易活动实施成本在一定程度上负有“历史责任”。

《关税与贸易总协定》(以下简称“GATT”)中也存在对CBDR 原则的反映和体现。例如,GATT 第三十六条提到,“……(丙)注意到发展中国家和其它国家之间的生活水平有一个很大的差距;(丁)认为单独和联合行动对促进发展中的各缔约国的经济发展,并使这些国家的生活水平得到迅速提高是必要的;……”“……(丙)在考虑采取本协定所许可的其它措施以解决某项特殊问题时,应特别注意发展中的缔约国的贸易利益;……”;30《关税与贸易总协定》第36、37 条。1979 年“东京回合”所通过的《对发展中国家的差别、更优惠待遇及对等和更充分参与问题的决定》中的规定也对CBDR 原则存在一定的反映和体现。

(三)国际海洋法法庭关于“担保个人和实体从事‘区域’内活动的国家的责任和义务”的第17 号咨询意见案

国际海洋法法庭(The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea,以下简称“ITLOS”)关于“担保个人和实体从事‘区域’内活动的国家的责任和义务”的第17 号咨询意见案(以下简称“第17 号咨询意见案”)由国际海底管理局理事会于2010 年5 月6 日向ITLOS 提出请求。在对“缔约国在担保‘区域’内活动方面负有哪些法律责任和义务?”这一问题进行解答时,ITLOS 在咨询意见第七部分“发展中国家的利益和需要”中进行了说明。

ITLOS 在咨询意见中首先对发展中国家和发达国家在关于担保国责任和赔偿责任的一般规定中的平等地位进行说明,指出这是为了防止方便担保国的扩散,并提出这些意见“并不排除规定担保国直接责任的规则可以为发达担保国和发展中担保国提供不同的待遇”。31参见International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area (Request for Advisory Opinion submitted to the Seabed Disputes Chamber), ITLOS website (15 Dec 2022), https://itlos.org/main/cases/list-ofcases/case-no-17/.但ITLOS 在咨询意见中仅提及规定这种“区别”的待遇的理论来源——《联合国海洋法公约》中涉及确保发展中国家开展“区域”内的活动并特别考虑它们的利益和需要的条款,包括序言、第140 条第1 款、第148条等。换言之,在国家对个人或实体在“区域”内的活动承担担保责任这一问题上,ITLOS 作出对发展中国家的优惠待遇,更多考虑的是发展中国家在能力上的不足,而未考虑类似气候变化领域内或前文提到的CBD、GATT 中的发达国家在历史上的责任。需要注意的是,ITLOS 考虑的能力也“只是对发达国家和发展中国家的差异的一种宽泛和不精确的称谓,重要的是一个国家在相关科学和技术领域的科学知识和技术能力水平。”32同上注。

四、CBDR 原则在海洋塑料污染国际立法中的适用性

(一)海洋塑料污染领域符合CBDR 原则适用的要件

如前所述,CBDR 原则适用的要件包括“发达国家应对环境问题承担历史责任”及“发达国家和发展中国家具备不同的能力”两方面要求,海洋塑料污染领域的发展情况与这两方面要求高度契合。

1.海洋塑料污染问题的产生主要归咎于发达国家的历史责任

UNEP 在其报告中曾提到,“全球产生的70 亿吨塑料垃圾中,只有不到10%被回收。数以百万吨计的塑料垃圾流失到环境中”“全球每年有近80%的河流塑料排放到海洋中,每年的排放量在80 万吨至270 万吨之间,其中小型城市河流污染最严重”。33United Nations Environment Programme, Our planet is choking on plastic, UNEP website(15 Dec 2022), https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/?gclid=EAIaIQobC hMIrur3y62m_AIVDJ1LBR24GQ5dEAAYASAAEgJBTfD_BwE.海洋塑料污染情况日益严重,而陆源塑料垃圾是海洋塑料污染,特别是海洋微塑料污染的主要来源之一,超过80%的海洋微塑料来源于陆源塑料废物。34参见[希]赫里西·K. 卡拉芭娜吉奥提、扬尼斯·K. 卡拉鲁吉奥提斯编著:《水和废水中的微塑料》,安立会等译,中国环境出版集团2022 年版,第1 页。

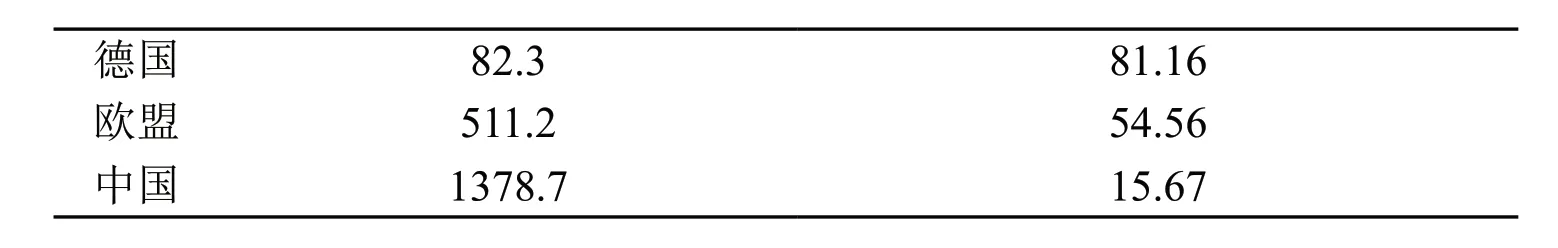

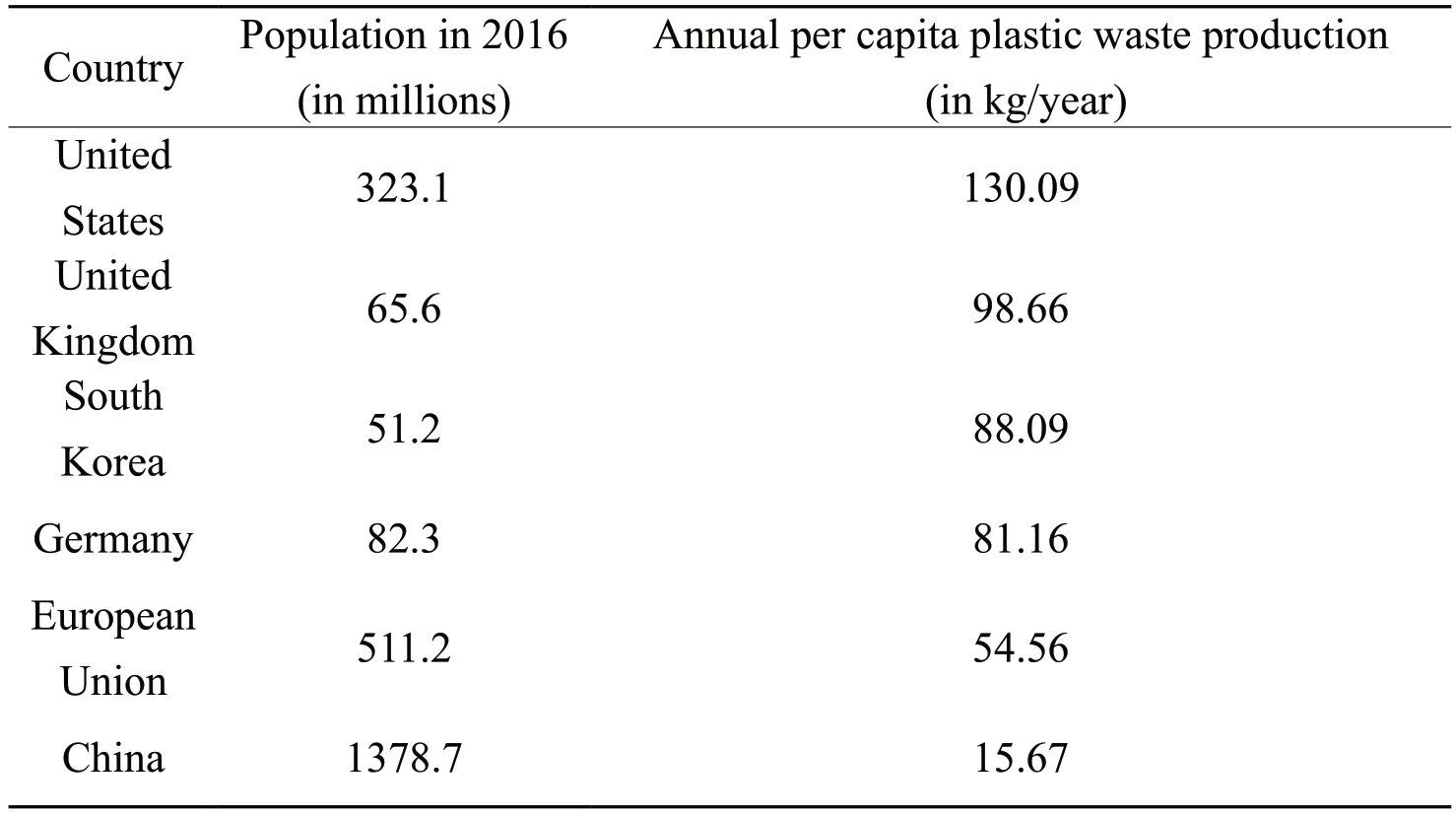

相较于发展中国家,发达国家的人均塑料垃圾年产量极高。根据Kara Lavender Law 等人2020 年的数据统计,2016 年,美国人口产生的塑料垃圾量居世界首位,人均塑料垃圾年产量也以超过130 千克/年居于世界首位,而欧盟尽管人口总量仅有中国的40%左右,但其产生的塑料垃圾总量仍超过中国;同时,人均塑料垃圾年产量处于高位的还有英国、德国、韩国等。35参见Kara Lavender Law et al., The United States’ contribution of plastic waste to land and ocean, Science Advances, Vol. 6:44, eabd0288 (2020).

德国 82.3 81.16欧盟 511.2 54.56中国 1378.7 15.67

上世纪七、八十年代,为了应对逐步恶化的环境问题,发达国家的环境政策日益严格。面对高昂的垃圾处理费用,发达国家选择将废弃物出口到发展中国家,以回避垃圾处理问题。正如美国国家科学院(National Academy of Sciences)在其2022 年的报告Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste 中所提到的,“在国际上,发达经济体通过向欠发达经济体出口塑料废物来外部化废物管理成本,这些经济体最终首当其冲地承受塑料废物的经济、社会和环境成本。2018 年之前,美国将大部分塑料垃圾出口到中国。在中国禁止大部分塑料垃圾进口后,美国将其出口的垃圾转移到其他东南亚国家。”37National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste, The National Academies Press, 2022, p. 30.

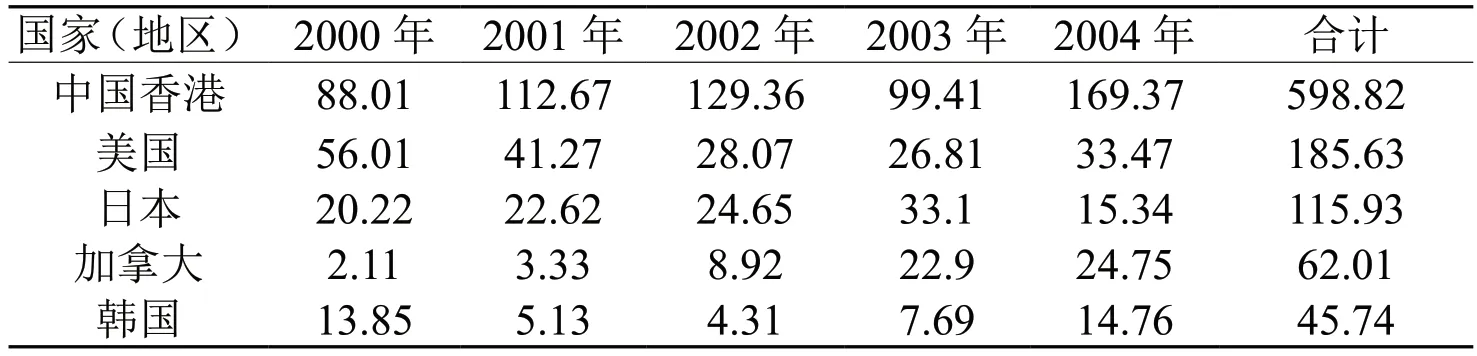

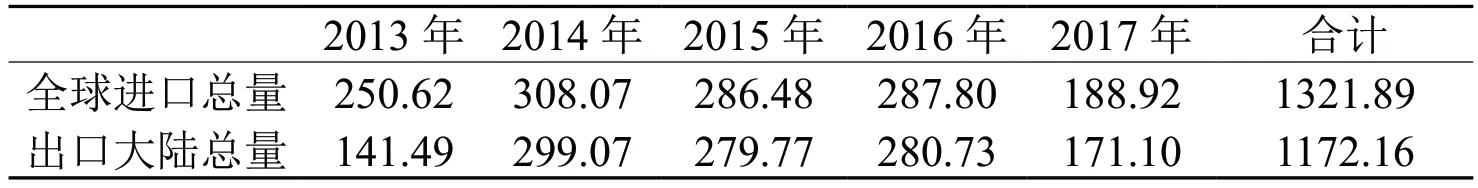

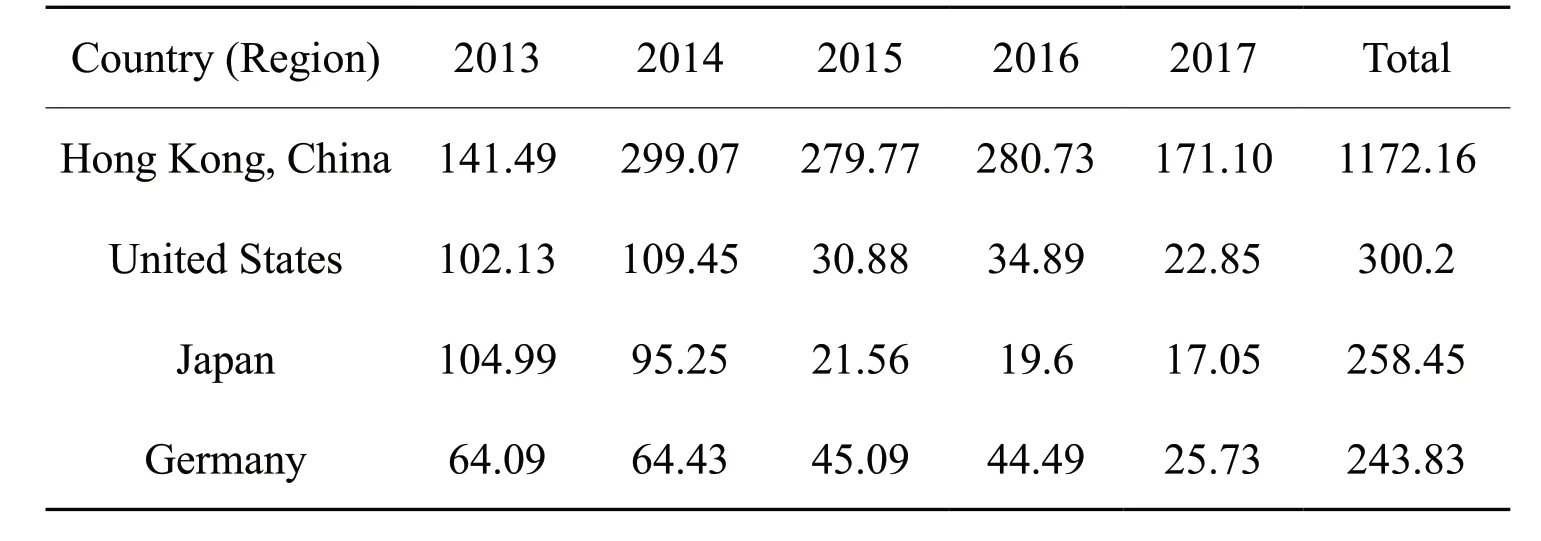

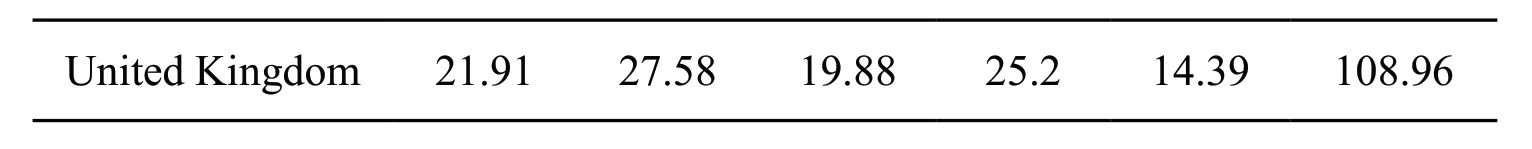

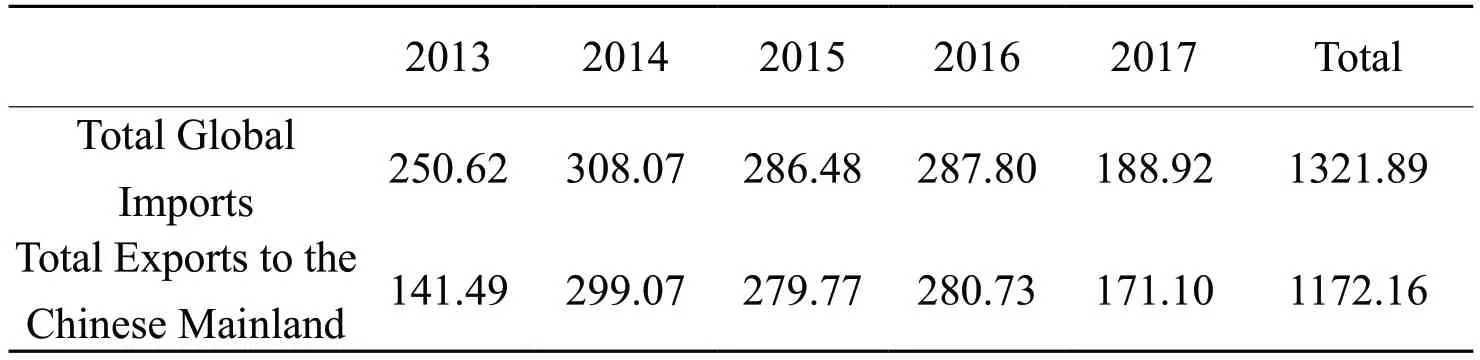

2017 年7 月18 日,国务院办公厅印发《关于禁止洋垃圾入境推进固体废物进口管理制度改革实施方案》(以下简称“禁废令”),我国正式全面禁止“洋垃圾”入境。在此之前,我国便是全球“洋垃圾”的最大目的地,而废塑料便是“洋垃圾”的“重要组成部分”。根据联合国商品贸易统计数据库(UN Comtrade)中2000-2004 年、2013-2017 年的进出口数据,中国香港、美国、日本、德国长期居于向我国出口废塑料的排名高位,换言之,中国曾经长期扮演发达国家“废塑料收集池”的角色。

需要说明的是,虽然根据表2、表3 的数据,我国香港地区长期居于向我国出口废塑料国家(地区)的排名高位,但其所出口的多是在当地进行转港的废塑料。从2013 至2017 年香港地区进、出口废塑料的数据的对比可以看出,香港实际上也承担了一部分进口废塑料的“消化”工作,这些废塑料的最初主要来源国仍是包括美国、日本、德国、英国在内的发达国家。

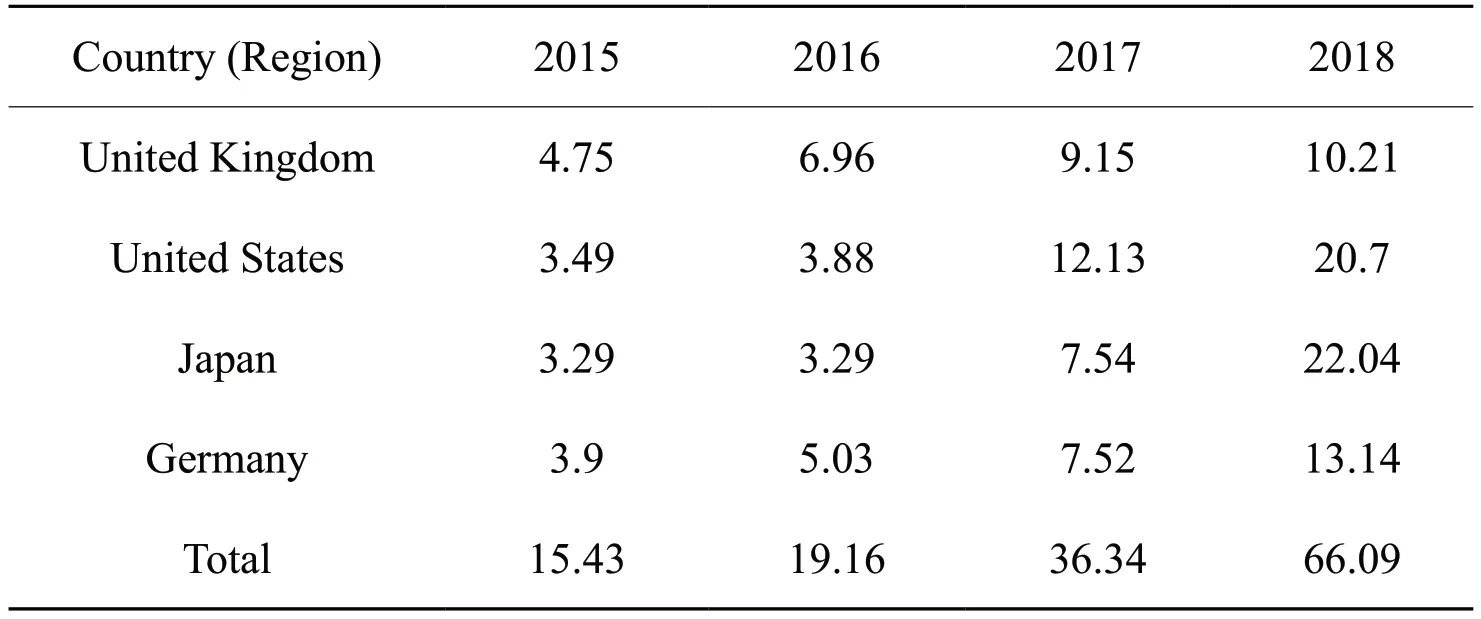

表2 2000 至2004年我国废塑料进口数据(单位:万吨)38表2 至表6 系作者根据联合国商品贸易统计数据库(UN Comtrade)中的数据制作的,数据保留小数点后两位。

表3 2013 至2017年我国废塑料进口数据(单位:万吨)

德国 64.09 64.43 45.09 44.49 25.73 243.83英国 21.91 27.58 19.88 25.2 14.39 108.96

表4 2013 至2017年香港废塑料进口与出口至中国大陆数据(单位:万吨)

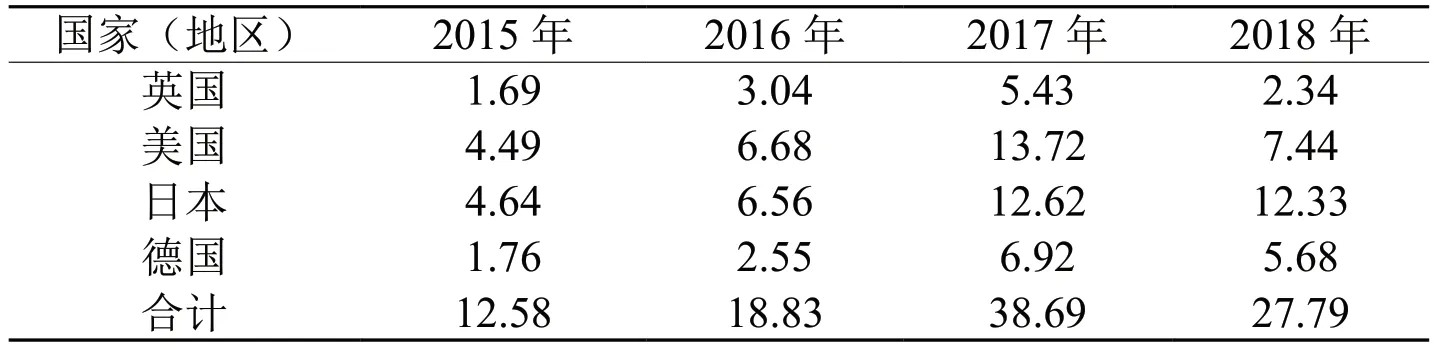

在我国“禁废令”出台后,发达国家将寻找转嫁废塑料处理成本的出口目的地的目光转向了东南亚国家,东南亚国家成为了发达国家出口废塑料的新倾销地。根据绿色和平组织(Greenpeace)发布的报告,东盟国家的废塑料进口全球占比从2016 年的5.38%直升至2018 年的27%。39Greenpeace, Southeast Asia’s Struggles against the Plastic Waste Trade, Greenpeace website, (15 Dec 2022), https://www.greenpeace.org/malaysia/publication/1905/southeastasias-struggle-against-the-plastic-waste-trade/.以越南和马来西亚为例,2015 年至2018 年,其废塑料的进口量大幅上升,近乎成倍增长,而这些废塑料的来源国仍然是发达国家。需要指出的是,马来西亚2018 年同样针对废塑料进口出台了多项限制政策,这也是马来西亚2018 年进口的废塑料总量相较2017 年减少的原因之一。

表5 我国“禁废令”出台前后越南废塑料进口数据(单位:万吨)

表6 我国“禁废令”出台前后马来西亚废塑料进口数据(单位:万吨)

不可否认,废塑料的进出口活动本身是一种商业行为,但发达国家采取将处理废塑料的责任转嫁至发展中国家的做法,本质上是在逃避其应承担的环境责任。仅以美国为例,美国人口仅占世界人口总量的4%,2016 年却制造了世界上17%的塑料垃圾,而其中大部分被出口到发展中国家。40同前注37, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, p. 50.废塑料向发展中国家的涌入,对发展中国家的生态平衡造成了严重破坏,加剧了当地的塑料污染,导致全球生态系统的健康状况进一步恶化,可以说,塑料污染现状的根源正是发达国家的责任规避与转移行为。

通过此前论述可以看出,部分发达国家在人均塑料垃圾年产量上远超发展中国家,且为了规避处理塑料垃圾的费用与责任,通过废塑料进出口活动将费用与责任转嫁至发展中国家。这种行为对塑料污染的现状是具有一定的促进作用,因此,部分发达国家对塑料污染的现状是负有类似气候变化领域中的“历史责任”的,符合CBDR 原则适用的第一项要件。

2.发达国家和发展中国家在治理海洋塑料污染方面存在较大的能力差异

从来源角度出发,废物管理不善是造成塑料污染的最大原因。41参见United Nations Environment Programme, Plastic Science, UNEP website, (27 Nov 2022), https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/41263/Plastic_Science_E.pdf.而废物管理与国家的经济能力水平、综合治理能力呈正相关。同时,海洋塑料污染治理是一项主要依靠国家能力完成的工作,涉及陆源废塑料回收与处理以及海洋微塑料的监测、采集与分析等内容。但由于发达国家和发展中国家之间的发展水平不同,人民的环保意识也存在较大的差异,执行国际环境条约的能力自然有所不同。42参见孙凯:《全球海洋塑料污染问题及治理对策》,载《国际治理》2021 年第15 期,第44-48 页。仅以海洋微塑料污染问题为例,目前对微塑料的来源与真实入海量尚存在认知上的不明确,也仍尚未形成较为稳定的处理方法。43参见尚胜美:《海洋微塑料污染状况及其应对措施建议》,载《资源节约与环保》2022年第2 期,第83-86 页。

UNEP 在第5/14 号决议“结束塑料污染:制定具有法律约束力的国际文书”以及INC-1 的设想说明中,也多次指出“同时考虑到各国的国情和能力”“同时考虑到《关于环境与发展的里约宣言》的原则以及各国的国情和能力等”,并要求政府间谈判委员会对能力建设、技术援助和资金进行讨论。44同前注1, United Nations Environment Programme; United Nations Environment Programme,End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument, UNEP website(27 Nov 2022), https://documents-d ds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/K22/007/33/pdf/K2200733.pdf?OpenElement.

因此,在海洋塑料污染领域,需要特别注重发展中国家的需求。发达国家在解决本国塑料污染问题的同时,应加强对发展中国家在技术、资金、能力建设等方面的支持。45参见联合国环境规划署:《中国代表团在塑料污染国际文书政府间谈判委员会第一次会议的一般性发言》,载联合国环境规划署网站,https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/china_inc-1_statements_0_0.pdf。可以说,在海洋塑料污染的治理方面,存在发展中国家与发达国家之间的较大的能力差别,符合CBDR 原则适用的第二项要件。

(二)海洋塑料污染国际立法的目的契合CBDR 原则的意涵

如前文所述,CBDR 原则的意涵包括“共同利益”与“实质公平”两方面内容,海洋塑料污染国际立法的主要目的在于解决这一全球性难题,在保护全球环境的同时,兼顾发展中国家的不同发展需求和能力差异。这意味着,海洋梳理污染的国际立法在目的上与CBDR 原则高度契合。

1.海洋塑料污染国际立法的“共同利益”

人类与环境是不可分割的,对环境进行保护也是对人类的生存进行保护。因此,人类需要共同努力,逐步改善、修复生存环境,共同面对挑战。

塑料作为上世纪新出现的高分子材料,以稳定的性质得到青睐,但也正因其特性,塑料在环境中并不易降解,而是在环境中不断累积。即使是所谓的“可降解塑料”的降解在符合严苛的降解条件下,也需要较长的时间,且其最终所能达到的真正降解水平也与塑料本身的种类与质量相关。46参见金琰等:《生物可降解塑料在不同环境条件下的降解研究进展》,载《生物科学学报》2022 年第5 期,第1784-1808 页。在海洋塑料污染领域,目前存在的主要问题是微塑料污染,基于目前的研究可以发现,微塑料在海洋各处的表层水体、海底沉积物都被监测到存在。47参见Ian Kane et al., Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation,Science, Vol. 368:6495, p. 1140-1145 (2020).

塑料导致的对海洋环境的危害是多角度、深层次的。具体而言,首先,微生物和藻类可在塑料表面附着、生长,受到洋流的影响,易跨界导致外来生物入侵,进而破坏被入侵区域内的原生生物栖息地;其次,由于微塑料的体积小,被海洋生物误食并进行消化后,在海洋生物链内形成富集,并最终随着人类对海洋生物的捕捞、食用而进入人体内部。48参见夏斌等:《微塑料在海洋渔业水域中的污染现状及其生物效应研究进展》,载《渔业科学进展》2019 年第3 期,第178-180 页。研究表明,在人类的血液内已发现微塑料的存在,49参见Chukwuma Muanya, Okra, Aloe employed to filter microplastics out of wastewater,the Guardian (31 Mar 2022), https://guardian.ng/features/health/okra-aloe-employed-tofilter-microplastics-out-of-wastewater/.尽管学者认为微塑料的人体的影响尚待证明,但世界卫生组织认为,人体对极小的微塑料吸收的可能性较高。50参见世界卫生组织:《世卫组织呼吁进一步研究微塑料并大力处理塑料污染问题》,载世界卫生组织网站,https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/detail/22-08-2019-who-callsfor-more-research-into-microplastics-and-a-crackdown-on-plastic-pollution。此外,未降解的塑料也容易被海洋生物误食并无法消化,导致海洋生物最终死亡。

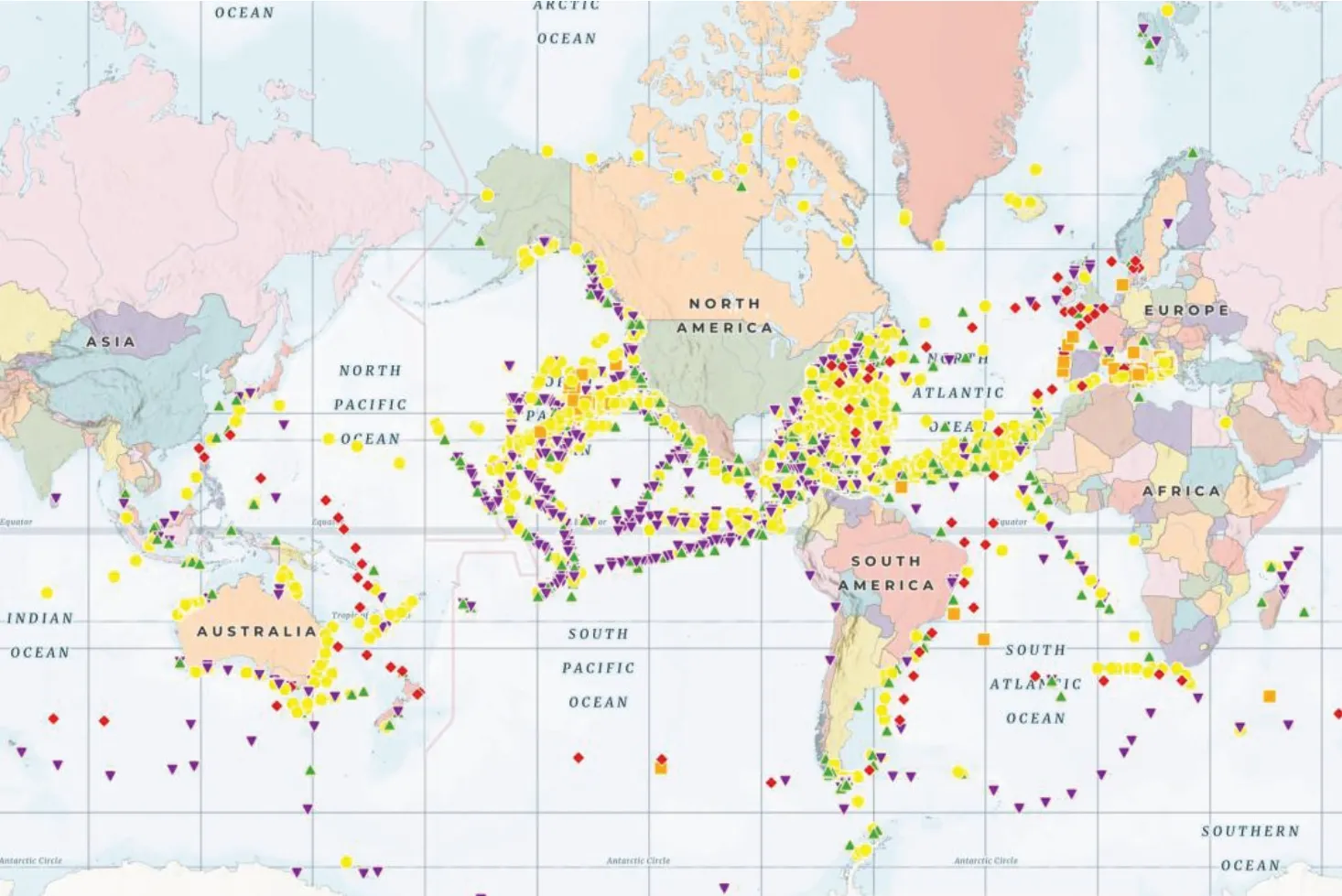

图2 海洋微塑料的全球分布51图2 系美国国家海洋和大气管理局制作的海洋微塑料浓度分布图,下载自https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/b296879cc1984fda833a8acc93e31476/page/Page/?views=Map-Viewer%2CDisplay-Filters。

海洋是地球生态系统的重要组成部分,而对地球生态环境的保护责任,世界各国都应承担,没有国家可以逃避这一责任。正如习近平总书记所言,“人类是命运共同体,保护生态环境是全球面临的共同挑战和共同责任。”52习近平:《推动我国生态文明建设迈上新台阶》,载《奋斗》2019 年第3 期,第1-16 页。塑料对海洋环境造成的影响,正在逐渐破坏海洋生态系统的稳定性,且对人类的健康安全造成潜在威胁,国际社会因此应当对海洋环境中的塑料污染承担共同责任。有学者认为,引入全生命周期方法(Full Life Cycle Approach, FLCA)将使CBDR 原则在未来的文书中被支持,但存在难以在情况和能力不同的国家间准确分配这种责任的问题。53参见WANG Sen, International law-making process of combating plastic pollution: Status Quo, debates and prospects, Marine Policy, Vol. 147, 105376 (2023).因此,在塑料污染国际文书的后续谈判中,尚需进一步对国家能力等内容进行更深层次的讨论。

2.海洋塑料污染国际立法的“实质公平”

发达国家将大量的废塑料向发展中国家转移,既极大减轻了处理废塑料所需的成本,又避免了处理废塑料过程中可能对其国内环境造成的潜在影响;发展中国家虽然从利用废塑料的过程中获得些许有限的利益,但受限于其能力,往往无法在处理废塑料的过程中避免污染扩散,从而导致其国内环境受到直接破坏。前文已对海洋塑料污染领域的“历史责任”与“国家能力”进行论述,而“历史责任”与“国家能力”两项要素也正是对实质公平的真正落实的两项决定性因素。因此,在海洋塑料污染领域内也存在“实质公平”的落实可能。

但是,这种落实可能需要建立在科学的分析与评估基础之上。笔者认为,结合目前的谈判情况,UNEP 在未来规制塑料污染的国际文书中,可以参考《巴黎协定》现有的规制模式,在对历史责任、国家能力和不同国情进行科学分析与评估的基础上,将对塑料污染,特别是海洋塑料污染应负较高责任的国家与受污染影响较大的国家进行区分,通过对国家自主贡献的通报与执行、技术转让、资金援助与能力建设等方式进行具体规定,赋予不同国家不同的责任,以期实质公平的最终落实,并将有利于塑料污染的实际治理。

五、结 语

尽管在现有的气候变化领域外的实践中并未明确将CBDR 原则列为一般原则,但其中的具体规定亦在一定程度上反映和体现了CBDR 原则,也有学者认为可以将CBDR 原则引入气候变化领域外的其他领域。通过对CBDR 原则的内涵、条约实践和判例的考察,并结合对该原则两大要素的分析,不难看出,在发达国家负有历史责任的塑料污染治理中,引入CBDR 原则具有一定的可行性。笔者认为,在INC-1 及INC-2 的会议进程中,部分国家代表团要求考虑在塑料污染的国际立法中纳入CBDR 原则的提议具有充分的理论和现实基础。

然而,从目前的谈判进展看,CBDR 原则的适用需要考虑多方面因素,特别是发达国家与发展中国家之间的政治意愿不同,如何在两大阵营中达成一致是一个巨大的挑战。因此,CBDR 原则最终能否引入新国际文书,仍需要参考INC 主席古斯塔沃·梅萨-夸德拉未来准备的国际文书“零草案”以及定于2023 年11 月13 至19 日于肯尼亚内罗毕召开的政府间谈判委员会第三届会议(INC-3)以及未来的后续谈判工作。

On the Applicability of the Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities in International Legislation on Marine Plastic Pollution

ZHOU Shengquan, SHI Yubing*

Abstract: The second session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, established by the United Nations Environment Programme to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, came to a close on 2 June 2023. Since the first session, delegations from several States, including China, have advocated for the incorporation of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in the future international instrument. However, there is currently no treaty practice that directly applies this principle in areas beyond climate change. In this context,this paper delves into the origins and implications of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and takes an empirical approach to analyze its applicability in international legislation on plastic pollution, particularly in the marine environment. The aim is to enable future international instruments regulating marine plastic pollution to effectively strike a balance between the interests of developed and developing States.

Key Words: Principle of common but differentiated responsibilities; Plastic pollution; Marine plastic pollution; UNEP; INC-2

* ZHOU Shengquan, South China Sea Institute, Xiamen University, China, e-mail:zhoushengquan@stu.xmu.edu.cn; SHI Yubing, Professor, South China Sea Institute, Ph.D in Law, Xiamen University, China.

©THE AUTHORS AND CHINA OCEANS LAW REVIEW

I. Introduction

In resolution 5/14 of 2 March 2022 entitledEndplasticpollution:Towards aninternationallegallybindinginstrument, the United Nations Environment Assembly requested the United Nations Environment Programme (hereinafter “UNEP”) to convene an intergovernmental negotiating committee to begin its work during the second half of 2022, with the ambition of completing that work by the end of 2024. The first and second sessions of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (hereinafter “INC”), established by1See United Nations Environment Programme, Scenario note for the first session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, UNEP website (27 Nov 2022), https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/4131 3/Scenario_note_E.pdf.UNEP to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment(hereinafter “INC-1” and “INC-2”, respectively), took place at Punta del Este Convention and Exhibition Center in Uruguay from 28 November to 2 December 2022, and at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization(UNESCO) Headquarters in Paris, France, from 29 May to 2 June 2023.

During the proceedings of INC-1 and INC-2, several delegations and contact groups, including those from States and regions including China, Argentina, Latin America and the Caribbean,2See International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 28 November 2022, ISSD website (10 Dec 2022), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marineenvironment-negotiating-committee-inc1-daily-report-28nov2022.South Africa, Senegal,3See International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 30 November 2022, ISSD website (10 Dec 2022), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marineenvironment-negotiating-committee-inc1-daily-report-30nov2022.India, the Philippines,4See International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 31 May 2023,ISSD website (7 Jun 2023), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environmentnegotiating-committee-inc2-daily-report-31may2023;and Contact Group 2,5See International Institute for Sustainable Development, Daily report for 1 June 2023, ISSD website (7 Jun 2023), https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environment-negotiatingcommittee-inc2-daily-report-1jun2023;called for the consideration of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (hereinafter “CBDR Principle”) in their general statements and discussions regarding the scope, objectives, and options for the structure of the instrument. These proposals represent the political will of some participating governments and should garner attention from the international community. However, there is no getting around the fact that the CBDR Principle has, thus far, been explicitly applicable only in the context of climate change. There remains a debate on whether this principle should be applicable to plastic pollution,particularly in the marine environment, which requires further exploration. To address this issue, this paper will embark on a two-fold journey. First, we will delve into the origins and implications of the CBDR Principle and provide a summary of its reflection and embodiment outside the field of climate change. Subsequently,we will conduct an in-depth analysis of the applicability of the CBDR Principle in the context of marine plastic pollution and provide insights into the specific ways it might be incorporated into future international instruments addressing plastic pollution.

II. Origins and Implications of the CBDR Principle

The CBDR Principle has gone through a significant period of development and intensive transformation, ultimately evolving to become a fundamental principle in the realm of climate change. In this section, the term “origins” refers to the evolution of the CBDR Principle specifically within the field of climate change,and the term “implications” refers to the essential concepts embodied by the CBDR Principle, namely, “common interests” and “substantive fairness”.6See JI Hua, Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and International Climate Change Legal Regime, China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2022, p. 64-72.

A.OriginsoftheCBDRPrinciple

The evolution of the CBDR Principle can be categorized into three stages:Initial formation, concrete establishment, and further development.

1. Initial Formation of the CBDR Principle

It is widely acknowledged in the academic community that the CBDR Principle began to take shape after the emergence of international environmental law. The birth of international environmental law was marked by the 1972 Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm and the adoption of theDeclarationofthe UnitedNationsConferenceontheHumanEnvironment(hereinafter “Stockholm Declaration”). For the first time,7See LIN Canling, et al., The Emergence and Development of International Environmental Law, People’s Court Press, 2006, p. 50. (in Chinese)theStockholmDeclarationintroduced the concepts of common and differentiated responsibilities in the field of the environment. For instance, theStockholmDeclarationprovided that “the protection and improvement of the human environment is a major issue which affects the wellbeing of peoples and economic development throughout the world; it is the urgent desire of the peoples of the whole world and the duty of all Governments”8Art. 2 of the Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.and that “the environmental policies of all States should enhance and not adversely affect the present or future development potential of developing countries…”9Art. 11 of the Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.Despite the cautiously phrased expression, it indeed implies the emergence of the concepts of “common responsibility” and “differentiated responsibility” at the time. However,the CBDR Principle was not firmly established during that period but rather in the “initial formation” stage. This was primarily due to the fact that the developing States, which later became key proponents of the CBDR Principle, had different priorities during the Conference on the Human Environment. Their focus was more on shaping a new international economic order rather than global environmental cooperation. Consequently, the conditions for solidifying the CBDR Principle were not yet ripe at that time.10See KOU Li, Common-but-differentiated Responsibilities: Its Evolution, Attributes and Functions, Science of Law (Journal of Northwest University of Political Science and Law),Vol. 4, p. 95-103. (in Chinese)

2. Establishment of the CBDR Principle

The CBDR Principle was explicitly set out in theUnitedNationsFramework ConventiononClimateChange(hereinafter “UNFCCC”), which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 May 1992 and opened for signature at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in June that same year, as well as in theRioDeclarationon EnvironmentandDevelopment(hereinafter “RioDeclaration”) adopted during the conference. It is provided in the preamble of UNFCCC that “… Acknowledging that the global nature of climate change calls for the widest possible cooperation by all States and their participation in an effective and appropriate international response, in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and their social and economic conditions …”11Preamble of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.Similarly,theRioDeclarationstates that “… In view of the different contributions to global environmental degradation, States have common but differentiated responsibilities…”12Principle 7 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development.

In the meantime, theRioDeclarationalso mentions that “… The developed countries acknowledge the responsibility that they bear in the international pursuit of sustainable development in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command.”13Ibid.This provision highlights the historical responsibility of developed States in addressing climate change, while also recognizing the current varying circumstances between developed and developing States. The two key elements of “historical responsibility” and “national capacity” embodied therein are seen as the foundational prerequisites for the application of the CBDR Principle.

In a nutshell, the provisions of the UNFCCC and theRioDeclarationreflect the global community’s perspective and stance towards climate change during the 1990s. They mark a period when countries were deepening their understanding of the CBDR Principle and seeking “substantive fairness” in addressing climate change. Regrettably, both instruments, while acknowledging the CBDR Principle,did not provide more detailed and specific provisions on that basis, leaving room for further development in the practical application of the CBDR Principle.

3. Further Development of the CBDR Principle

The CBDR Principle was made concrete in theKyotoProtocol, which was adopted at the third session of the Conference of Parties to the UNFCCC in 1997. In simple terms, theKyotoProtocoldelineated greenhouse gas reduction commitments for developed States while not imposing mandatory reduction obligations on developing States. The protocol’s dichotomy approach, characterized by strict adherence to the CBDR Principle, ignited substantial disagreements and more heated debates between developed and developing States regarding the principle’s applicability, surpassing previous levels of contention.

TheParisAgreement, adopted in 2015, set a clear course and objectives for global collaboration in addressing climate change beyond 2020. It is widely recognized as a holistically balanced, long-lasting, and effective international climate accord that is legally binding.14ZHU Lisong & GAO Xiang, From Copenhagen to Paris: Changes and Developments in the International Climate Regime, Tsinghua University Press, 2017, p. 247. (in Chinese)While the CBDR Principle is explicitly mentioned multiple times in theParisAgreement, its content has evolved to include elements of “common but differentiated responsibilities, respective capabilities, and different national circumstances”.15ZHOU Chen, On the Common But Differentiated Responsibilities Principle In the Context of Carbon Neutrality, Wuhan University Journal (Philosophy & Social Science), Vol. 2, p.152-163 (2023). (in Chinese)The previous dichotomy approach established by theKyotoProtocol, which mandated emission reductions for developed States and voluntary participation for developing States, has transitioned into a new model based on “nationally determined contributions”, where all parties are included in the scope of greenhouse gas emissions reduction efforts.16Art. 4 of the Paris Agreement.Following theParis Agreement, theGlasgowClimatePact, adopted at the twenty-sixth session of the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, maintained a steadfast stance on the CBDR Principle, and it reviewed and reaffirmed the provisions related to the CBDR Principle outlined in theParisAgreement.17United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Glasgow Climate Pact,UNFCCC website (15 Dec 2022), https://unfccc.int/documents/310475.

B.ImplicationsoftheCBDRPrinciple

It is evident from the above that the CBDR Principle itself is constantly evolving and changing. Some scholars argue that, over the years, there has been a significant shift in the implications of the CBDR Principle, particularly in relation to its two elements: “Common responsibility” and “differentiated responsibility”.18See SHI Yubing, Climate Change and International Shipping: The Regulatory Framework for the Reduction of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Brill Nijhoff, 2017, p. 86-89.However, this paper holds that the essence of the CBDR Principle has not undergone substantial changes. As indicated by the name itself, the principle encompasses two aspects - common and differentiated responsibility -which directly convey the implications of the CBDR Principle, namely, “common interests” and “substantive fairness”.19Supra note 6, JI Hua. (in Chinese)

1. Common Interests Embodied in Common Responsibility

As previously mentioned, the concept of “common responsibility” initially appeared in theStockholmDeclarationand was further acknowledged in subsequent instruments such as the UNFCCC and theKyotoProtocol. The primary rationale behind advocating for common responsibility among States in the realms of both environment and climate change lies in the holistic nature of Earth’s ecosystem. Any harm inflicted on a component within this interconnected system will inevitably have repercussions on the entire ecosystem. Furthermore, there exists a direct correlation between the common interests of humanity and Earth’s ecosystem as a whole. Therefore, issues related to the environment and climate change have impacts on humanity at the level of common interests. It is for this reason that all States need to assume common responsibility for these issues.

2. Substantive Fairness Embodied in Differentiated Responsibility

In the pursuit of substantive fairness, the CBDR Principle introduces the concept of “differentiated responsibility”. According to Principle 7 of theRio Declaration, this differentiated responsibility arises from two main sources:the historical responsibility of a State and its current national capacity. As previously mentioned, these two key elements are considered prerequisites for the application of the CBDR Principle.20Supra note 12.Since the Industrial Revolution, long-standing industrialized developed States have caused unprecedented destruction to Earth’s ecosystem, which is a major contributor to the current environmental status. In response to the environmental damage within their own borders, these developed States have started relocating high-pollution and high-emission industries to areas outside their borders, shifting pollution and emissions to developing States.Additionally, developed States, albeit having a relatively small population in the global context, constitute the major contributors to the current global environmental pollution. Based on the Polluter-pays Principle, developed States should take historical responsibility for environmental damage. On the other hand, developing States, constrained by their current national capacity, have limited capabilities for environmental governance after undertaking the pollution and emissions transferred to them from developed States. They often struggle to fully express their intentions through their own resources. Furthermore, many developing States are populous nations, and to protect their people’s livelihoods, they must further industrialize to boost economic growth. Therefore, to achieve substantive fairness between developing and developed States, it is essential for these nations to shoulder differentiated responsibilities.

Considering the varying capacities and unique national circumstances of developing States, theParisAgreementacknowledges the challenges these nations encounter when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, it offers relatively flexible provisions for developing States, essentially allowing the practical application of differentiated responsibilities. Beyond the previously mentioned nationally determined contributions, theParisAgreementalso includes detailed provisions concerning financial support, technology transfer, and capacitybuilding. Notably, it provides concrete measures for strengthening capacitybuilding efforts.21See Art. 11 of the Paris Agreement.

III. Reflection and Embodiment of the CBDR Principle Outside the Field of Climate Change

While the CBDR Principle initially emerged and evolved within the realm of climate change, there exist treaties and precedents that can reflect and embody the CBDR Principle in fields beyond climate change.

A.ConventiononBiologicalDiversity

Since 1988, when British ecologist Norman Myers first identified tropical rainforest “hotspots” with exceptional levels of plant endemism and serious levels of habitat loss,22See Norman Myers, Threatened biotas: “Hot spots” in tropical forests, Environmentalist,Vol. 8:3, p. 187-208 (1988).multiple intergovernmental organizations have worked for years to identify a total of 36 “biodiversity hotspots” by 2016. These hotspots are recognized as Earth’s most biologically rich—yet threatened—terrestrial regions.23See Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Biodiversity Hotspots Defined, CEPF website (15 Dec 2022), https://www. cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/hotspots-defined.

Figure 1 Global Distribution Map of Biodiversity Hotspots24Figure 1 is a map of the global distribution of biodiversity hotspots produced by Kellee Koenig, see https://zenodo.org/record/4311850#.Y66f FfVBze9。

The global distribution of biodiversity hotspots reveals that the majority of biodiversity is currently found in developing States across South-East Asia, Africa,and South America. However, due to capacity constraints, developing States often struggle to effectively protect their biodiversity. Additionally, in the realm related to biodiversity utilization like biotechnology, it wasn’t until the 21st century that significant advancements emerged in these nations.25See The World Academy of Science, Biotechnology: A growing field in the developing world, TWAS website (15 Dec 2022), https://twas.org/article/biotechnology-growing-fielddeveloping-world.Historically, the utilization of biodiversity was primarily the domain of developed States. As a consequence,many of these nations have already witnessed substantial losses in their own biodiversity. Therefore, developed States, owing to their historical responsibility,have a duty to financially support biodiversity conservation efforts in developing States and to share the benefits reaped from utilizing biodiversity with developing States.

Although the CBDR Principle is not explicitly mentioned in theConvention onBiologicalDiversity(hereinafter “CBD”), it is implicitly reflected and embodied in the CBD’s text. For instance, the preamble of CBD states that “Affirming that the conservation of biological diversity is a common concern of humankind”.Article 20, paragraph 2 thereof provides that “The developed country Parties shall provide new and additional financial resources to enable developing country Parties to meet the agreed full incremental costs to them of implementing measures which fulfill the obligations of this Convention and to benefit from its provisions”.26Preamble, Article 20 (2) of the Convention on Biological Diversity.Additionally, Articles 15, 16, and 19 of the CBD, which address access to genetic resources, access to and transfer of technology, and handling of biotechnology and distribution of its benefits, respectively, effectively manifest the differentiation in responsibility between developed and developing States. Some scholars argue that the “Rio Principles”, including the CBDR Principle, should serve as the foundational pillars of the CBD framework, emphasizing that developed States should acknowledge their historical responsibility regarding biodiversity loss.27See Viviana Muñoz Tellez, Proposals to Advance the Negotiations of the Post 2020 Biodiversity Framework, the South Centre website, (15 Dec 2022), https://www.southcentre.int/policy-brief-90-march-2021/.

B.GeneralAgreementonTariffsandTrade

Within numerous agreements of the World Trade Organization (hereinafter “WTO”), developing States are offered more lenient obligations, such as special preferences, technical assistance, and phased implementation.28See Joost Pauwelyn, The End of Differential Treatment for Developing Countries?Lessons from the Trade and Climate Change Regimes, Review of European Community &International Environmental Law, Vol. 22:1, p. 29-41 (2013).In the realm of trade mechanisms, it can be said that the WTO acknowledges the disparities in national capacity and development needs between developing and developed States, and as a result, grants them correspondingly “differentiated” obligations.Some scholars argue that developed States should shoulder “a moral responsibility to pay a disproportionate share of the costs”.29See Robyn Eckersley, Understanding the interplay between the climate and trade regimes,Climate and Trade Polici es in a Post-2012 World, United Nations Environment Programme,2009, p. 11-18.This perspective stems from the fact that developed States have historically reaped significant benefits from trade, while developing States face considerably higher costs in conducting trade activities.These costs can be attributed, in part, to historical actions such as the colonization perpetrated by developed States against developing States. In other words,developed States bear a certain level of “historical responsibility” for the elevated costs associated with trade activities in developing States.

The CBDR Principle is also reflected and embodied in theGeneralAgreement onTariffsandTrade(hereinafter “GATT”). For instance, Article XXXVI of the GATT mentions that “… (c) noting, that there is a wide gap between standards of living in less-developed countries and other countries; (d) recognizing that individual and joint action is essential to further the development of the economies of less-developed contracting parties and to bring about a rapid advance in the standards of living in these countries; … ”, and that “… (c) have special regard to the trade interests of less-developed contracting parties when considering the application of other measures permitted under this Agreement to meet particular problems …”30Arts. 36, 37 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.Additionally, provisions within theDecisiononDifferential&More FavorableTreatment,Reciprocity&FullerParticipationofDevelopingCountries,adopted in the Tokyo Round in 1979, also reflect and embody the CBDR Principle to some extent.

C.AdvisoryOpinionNo.17oftheInternationalTribunalfortheLawof theSeaontheResponsibilitiesandObligationsofStatesSponsoring PersonsandEntitieswithRespecttoActivitiesintheArea

Advisory Opinion No. 17 of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea(hereinafter “ITLOS”) on the Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area (hereinafter “Advisory Opinion No. 17”) was requested by the Council of the International Seabed Authority and submitted to ITLOS on 6 May 2010. In addressing the question “What are the legal responsibilities and obligations of States Parties to the Convention with respect to the sponsorship of activities in the Area”, ITLOS provided explanations in Part VII “Interests and needs of developing States” of the advisory opinion.

In the Advisory Opinion, ITLOS first clarified that the general provisions concerning the responsibilities and liability of the sponsoring State apply equally to all sponsoring States, whether developing or developed. This is to prevent the spread of sponsoring States “of convenience”. ITLOS also noted that these observations “do not exclude that rules setting out direct obligations of the sponsoring State could provide for different treatment for developed and developing sponsoring States.”31See International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area (Request for Advisory Opinion submitted to the Seabed Disputes Chamber), ITLOS website (15 Dec 2022), https://itlos.org/main/cases/list-ofcases/case-no-17/.However, in the Advisory Opinion, ITLOS only mentioned the theoretical basis for such “differentiated” treatment, which stems from provisions in theUnitedNationsConventionontheLawoftheSea(UNCLOS)concerning the facilitation of activities in the Area by developing States and special consideration for their interests and needs, as found in the preamble, Article 140(1),Article 148, among others. In other words, concerning the issue of States assuming sponsoring responsibilities for persons or entities with respect to activities in the Area, ITLOS extends preferential treatment to developing States, primarily considering their inadequate capabilities while leaving out of consideration the historical responsibilities of developed States akin to those discussed in the context of climate change or as mentioned in CBD and GATT. It is important to note that the reference to “capabilities” by ITLOS “is only a broad and imprecise reference to the differences in developed and developing States. What counts in a specific situation is the level of scientific knowledge and technical capability available to a given State in the relevant scientific and technical fields.”32Ibid.

IV. Applicability of the CBDR Principle in International Legislation on Marine Plastic Pollution

A.TheFieldofMarinePlasticPollutionMeetstheElementsforthe ApplicationoftheCBDRPrinciple

As noted earlier, the elements for the application of the CBDR Principle include two key aspects: “developed States bearing historical responsibility for environmental issues” and “differing capabilities between developed and developing States.” The development situation of marine plastic pollution aligns closely with these two requirements.

1. The Emergence of Marine Plastic Pollution Largely Attributable to the Historical Responsibility of Developed States

According to a report by UNEP, “Of the seven billion tonnes of plastic waste generated globally so far, less than 10 per cent has been recycled. Millions of tonnes of plastic waste are lost to the environment,” and “nearly 80% of global annual riverine plastic emissions into the ocean, which range between 0.8 and 2.7 million tonnes per year, with small urban rivers amongst the most polluting.”33United Nations Environment Programme, Our planet is choking on plastic, UNEP website(15 Dec 2022), https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/?gclid=EAIaIQobC hMIrur3y62m_AIVDJ1LBR24GQ5dEAAYASAAEgJBTfD_BwE.With regard to the increasingly serious situation of marine plastic pollution, landbased plastic waste constitutes a major contributor to marine plastic pollution, in particular marine microplastic pollution. Over 80 per cent of marine microplastics originate from land-based plastic waste.34See Hrissi K. Karapanagioti, Ioannis K. Kalavrouziotis: Microplastics in Water and Wastewater, translated by AN Lihui, et al., China Environment Publishing Group, 2022, p. 1.(in Chinese)

Compared to developing States, developed States exhibit extremely high per capita plastic waste generation. According to data from Kara Lavender Law et al. in 2020, in 2016, the United States population generated the world’s largest amount of plastic waste, as did its annual per capita plastic waste production, surpassing 130 kilograms per person per year. The European Union, despite having a population roughly 40% that of China, still generated more plastic waste than China in total.Additionally, States like the United Kingdom, Germany, and South Korea also showed notably high per capita plastic waste production.35See Kara Lavender Law et al., The United States’ contribution of plastic waste to land and ocean, Science Advances, Vol. 6:44, eabd0288 (2020).

Table 1 Ranking of Annual per Capita Plastic Waste Production in Selected Countries, 201636Table 1 was produced by this paper based on data from the paper The United States’contribution of plastic waste to land and ocean by Kara Lavender Law et al.

The 1970s and 1980s saw increasingly stringent environmental policies in developed States in response to progressively worsening environmental issues.These States, faced with high waste disposal costs, chose to export their waste to developing States in order to avoid the problem of waste disposal. As the National Academy of Sciences highlighted in its 2022 reportReckoningwiththeU.S.Rolein GlobalOceanPlasticWaste, “Internationally, advanced economies externalize the cost of waste management by exporting plastic waste to less advanced economies,who ultimately bear the brunt of the economic, social, and environmental costs of plastic waste. Before 2018, the United States exported most of its plastic waste to China. After China banned most plastic waste imports, the United States diverted its exported waste to other Southeastern Asian countries.”37National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Reckoning with the U.S. Role in Global Ocean Plastic Waste, The National Academies Press, 2022, p. 30.

On 18 July 2017, the General Office of the State Council issued theImplementationPlanforProhibitingtheEntryofForeignGarbageandAdvancing theReformoftheSolidWasteImportAdministrationSystem(hereinafter “Waste Ban”), marking China’s official ban on the entry of “foreign waste”. Prior to this,China was the largest destination for “foreign waste” worldwide, and plastic waste was a vital part of it. According to the import and export data from 2000 to 2004 and 2013 to 2017 in the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade), Hong Kong, China, the United States, Japan, and Germany had long been among the top exporters of plastic waste to China, which means that China had long served as a “plastic waste collection pool” for developed States.

Note that, in spite of the Hong Kong region’s longstanding high ranking in the list of countries (regions) exporting plastic waste to China, as shown in Tables 2 and 3, much of this exported plastic waste was actually transshipped locally within Hong Kong. By comparing the import and export data of plastic waste in Hong Kong from 2013 to 2017, it becomes evident that Hong Kong had played a part in processing and handling a portion of the imported plastic waste, which still originally came from developed States including the United States, Japan, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Table 2 China’s Plastic Waste Import Data in 2000-2004 (unit: 10,000 tons)38Tables 2-6 were produced by this paper based on data from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade), with the data retained to two decimal places.

Table 3 China’s Plastic Waste Import Data in 2013-2017 (unit: 10,000 tons)

United Kingdom 21.91 27.58 19.88 25.2 14.39 108.96

Table 4 Hong Kong’s Imports of Plastic Waste and Exports to the Chinese Mainland, 2013-2017 (unit: 10,000 tons)

Following China’s implementation of the Waste Ban, developed States shifted their focus to Southeast Asian nations as new destinations for exporting plastic waste in an attempt to transfer the cost of waste disposal. According to a report by Greenpeace, the global share of waste plastic imports from ASEAN countries rose dramatically from 5.38% in 2016 to 27% in 2018.39Greenpeace, Southeast Asia’s Struggles against the Plastic Waste Trade, Greenpeace website, (15 Dec 2022), https://www.greenpeace.org/malaysia/publication/1905/southeastasias-struggle-against-the-plastic-waste-trade/.For instance, Vietnam and Malaysia experienced a sharp and almost exponential rise in their imports of plastic waste from 2015 to 2018, with the waste source countries remaining developed States. It is worth noting that Malaysia also implemented a number of restrictive policies on plastic waste imports in 2018, which contributed to a decrease in the total amount of plastic waste it imported compared to 2017.

Table 5 Vietnam’s Plastic Waste Imports before and after China’s Introduction of Waste Ban (unit: 10,000 tons)

Table 6 Malaysia’s Plastic Waste Imports before and after China’s Introduction of Waste Ban (unit: 10,000 tons)

Undoubtedly, the import and export of plastic waste is a commercial activity in itself. However, the practice adopted by developed States of shifting the responsibility for waste plastic disposal to developing States is essentially an attempt to evade their environmental responsibility. Taking the United States alone as an example, albeit having only 4% of the world’s total population, it produced 17% of the world’s plastic waste in 2016, most of which was exported to developing States.40Supra note 37, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, p. 50.This influx of plastic waste into developing States has led to severe disruptions in their ecological balance, exacerbating local plastic pollution,which, in turn, contributes to the further deterioration of the global ecosystem’s health. It can be argued that the root cause of the current plastic pollution situation lies precisely in the behavior of developed States seeking to evade and transfer their responsibility.

As discussed earlier, it is evident that some developed States have significantly higher per capita plastic waste production compared to developing States.Furthermore, in an attempt to evade the costs and responsibilities associated with plastic waste disposal, they have transferred these burdens to developing States through plastic waste import and export activities. Such behavior has contributed to the current state of plastic pollution. It follows that some developed States bear a “historical responsibility” for the current state of plastic pollution similar to that in the field of climate change, which is in line with the first element for the application of the CBDR Principle.

2. Large Differences in Capacity between Developed and Developing States to Address Marine Plastic Pollution

From a source perspective, inadequate waste management stands out as the primary driver of plastic pollution.41See United Nations Environment Programme, Plastic Science, UNEP website, (27 Nov 2022), https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/41263/Plastic_Science_E.pdf.Waste management correlates positively with a State’s economic capacity and overall governance capabilities. Additionally,addressing marine plastic pollution involves a range of activities that largely depend on a State’s capabilities, including the recycling and disposal of land-based plastic waste, as well as monitoring, collection, and analysis of microplastics in the oceans. However, the capacity of developed and developing States to implement international environmental instruments varies from each other due to their differing levels of development and varying levels of environmental awareness among their populations.42See SUN Kai, Global Marine Plastic Pollution and Its Countermeasures, Governance, Vol.15, p. 44-48. (in Chinese)To illustrate, when it comes to microplastic pollution in the oceans, there is still uncertainty surrounding the sources and actual quantity of microplastics entering the marine environment. Furthermore, a more reliable method for dealing with microplastics has yet to be developed.43See SHANG Shengmei: Pollution Status of Marine Microplastics and Countermeasures,Resources Economization & Environmental Protection, Vol. 2, p. 83-86. (in Chinese)

In UNEA Resolution 5/14 entitled “End plastic pollution: Towards an international legally binding instrument” and the concept note for INC-1, there are multiple instances where it emphasizes “taking into account national circumstances and capabilities” and “taking into account, among other things, the principles of theRioDeclaration, as well as national circumstances and capabilities”. It also calls for the intergovernmental negotiating committee to engage in discussions regarding capacity building, technology transfer, and financial support.44Supra note 1, UNEP; United Nations Environment Programme, End plastic pollution:towards an international legally binding instrument, UNEP website (27 Nov 2022),https://documents-d ds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/K22/007/33/pdf/K2200733.pdf?OpenElement.

Hence, in tackling marine plastic pollution, it is crucial to prioritize the needs of developing States. Developed States should not only address their own plastic pollution issues but also enhance their assistance to developing States in terms of technology, funding, and capacity building.45See UNEP, General Statement by the Delegation of China at the First Session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an International Legally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, UNEP website, https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/china_inc-1_statements_0_0.pdf. (in Chinese)It can be contended that there exists a significant disparity in the capacity of developing and developed States to manage marine plastic pollution, thereby fulfilling the second element for the application of the CBDR Principle.

B.ThePurposeofInternationalLegislationonMarinePlasticPollution AlignswiththeImplicationsoftheCBDRPrinciple

As previously discussed, the implications of the CBDR Principle encompass two elements: “common interests” and “substantial fairness”. The primary objective of international legislation on marine plastic pollution is to tackle this global issue and safeguard the global environment, all while considering the varying development needs and capacity disparities among developing States. This implies that international legislation on marine plastic pollution aligns closely with the CBDR Principle.

1. “Common Interests” in International Legislation on Marine Plastic Pollution

The interdependence of humans and the environment underscores the vital need to protect both. Preserving the environment is, fundamentally, preserving the essence of human survival. Consequently, a joint global effort is imperative to progressively enhance and restore the living environment, while confronting the challenges collectively.

Plastics, as new polymer materials that emerged in the last century, have gained popularity due to their stability. However, it is precisely these characteristics that make plastics challenging in the environment because they don’t readily break down but rather accumulate over time. Even plastics labeled as “degradable” will take a considerable amount of time to degrade under strict degradation conditions,and the ultimate extent of degradation depends on the type and quality of the plastic itself.46See JIN Yan, et al., Advance in the degradation of biodegradable plastics in different environments, Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, Vol. 5, p.1784-1808 (2021).In the realm of marine plastic pollution, the prevailing issue is microplastic pollution. Current research indicates that microplastics have been detected in surface waters and seafloor sediments across various marine regions.47See Ian Kane, et al., Seafloor microplastic hotspots controlled by deep-sea circulation,Science, Vol. 368:6495, p. 1140-1145 (2020).

Figure 2 Global distribution of marine microplastics48Figure 2 is a map of marine microplastic concentrations produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States, see https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/b296879cc1984fda833a8acc93e31476/page/Page/?views=Map-Viewer%2CDisplay-Filters.

Plastic pollution poses multidimensional and deep-seated threats to the marine environment. Firstly, microorganisms and algae can attach to and grow on the surface of plastics. Due to ocean currents, these plastics can be easily carried across borders, allowing foreign organisms to invade and destroy the habitats of native organisms in the affected areas. Secondly, microplastics, being very small in size,can be mistakenly ingested by marine organisms.49See XIA Bing, et al., Research Progress on Microplastics Pollution in Marine Fishery Water and Their Biological Effects, Progress in Fishery Sciences, Vol. 3, p. 178-180 (2019).Once ingested, they accumulate within the marine food chain, eventually making their way into the human body when humanity fish and consume seafood.50See Chukwuma Muanya, Okra, Aloe employed to filter microplastics out of wastewater, the Guardian (31 Mar 2022), https://guardian.ng/features/health/okra-aloe-employed-to-filtermicroplastics-out-of-wastewater/.Research has found microplastics in human blood, and although scholars believe that the exact effects on human health are still uncertain, the World Health Organization acknowledges that there is a higher likelihood of human absorption of tiny microplastics.51See WHO, WHO calls for more research into microplastics and a crackdown on plastic pollution, WHO website (22 Aug 2019), https://www.who.int/zh/news-room/detail/22-08-2019-who-calls-for-more-research-into-microplastics-and-a-crackdown-on-plasticpollution. (in Chinese)Additionally, marine life often ingests by mistake undegraded plastics, which they cannot digest, leading to their eventual death.

The oceans and seas constitute a crucial element within earth’s ecosystem,and the responsibility for safeguarding the planet’s ecological environment is a shared obligation among all States. No State can shirk that duty. As XI Jinping has articulated, “Humanity is a community with a shared future, and thus protecting the environment is a challenge and a duty which all of us around the globe must face together.”52XI Jinping, Pushing China’s Development of an Ecological Civilization to a New Stage,Fendou, Vol. 2019:3, p. 1-16.Plastic pollution is gradually eroding the stability of marine ecosystems and potentially jeopardizing human health and safety. Consequently,the international community must take collective responsibility for addressing this issue. Some scholars argue that incorporating the Full Life Cycle Approach (FLCA)could garner support for the CBDR Principle in future instruments. However, it poses challenges in accurately allocating responsibilities among States with varying national circumstances and capabilities.53See WANG Sen, International law-making process of combating plastic pollution: Status Quo, debates and prospects, Marine Policy, Vol. 147, 105376 (2023).Hence, in the subsequent negotiations regarding international instruments on plastic pollution, there is a need for more indepth discussions on topics such as national capacities.

2. “Substantive Fairness” in International Legislation on Marine Plastic Pollution

Developed States’ transfer of significant amounts of plastic waste to developing States substantially reduces their costs associated with waste disposal and also sidesteps the potential environmental ramifications that might emerge during the waste disposal process within their own territories. In contrast, developing States,albeit with limited benefits from the utilization of plastic waste, are often unable to avoid the spread of contamination during the waste disposal process due to their restricted capacities, leading to direct damage to their domestic environments. As discussed earlier, the elements of “historical responsibility” and “national capacity” in the context of marine plastic pollution have been elucidated. These two elements are also two determinants in the practical implementation of substantive fairness.Therefore, there is potential for the realization of substantive fairness in the realm of marine plastic pollution.

Nonetheless, this practical implementation may need to be underpinned by thorough scientific analysis and assessment. In light of the current state of negotiations, as this paper holds, UNEP can take a page from the regulatory model seen in theParisAgreementfor future international instruments on plastic pollution. Building upon a scientific analysis and assessment of the historical responsibility, national capacity, and unique national circumstances, UNEP can differentiate between States with greater responsibility for plastic pollution,particularly in the marine environment, and those significantly affected by it.Also, specific provisions can be made for the notification and implementation of nationally determined contributions, technology transfer, financial support, and capacity-building to assign responsibilities to various States. The aim is to finalize the implementation of substantive fairness, which will be conducive to the actual management of plastic pollution.

V. Conclusion

Notwithstanding an absence of the CBDR Principle being explicitly listed as a general principle in existing practices outside the field of climate change,the specific provisions therein do, to some extent, reflect and embody the CBDR Principle. There are also some scholars arguing that the CBDR Principle can be extended to fields beyond climate change. By delving into the essence of the CBDR Principle, treaty practices, and precedents, along with an analysis of the two main elements of the CBDR Principle, it becomes evident that introducing the CBDR Principle into the governance of plastic pollution, where developed States bear historical responsibility, is feasible. In the opinion of this paper, the proposal made by certain State delegations during the INC-1 and INC-2 to consider incorporating the CBDR Principle into international legislation on plastic pollution is wellfounded, both theoretically and practically.

However, the current progress of negotiations reveals that the application of the CBDR Principle must be carefully considered in light of various factors.Notably, given the divergent political wills between developed and developing States, reaching consensus among the two major camps poses a significant challenge. As such, whether the CBDR principle can ultimately be integrated into new international instruments hinges on the “zero draft” international instrument being prepared by INC Chair Gustavo Meza-Cuadra, as well as the upcoming third session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-3) scheduled to convene in Nairobi, Kenya from 13 to 19 November 2023, and subsequent negotiations.

Translators: CHEN Cong, YAN Lilan

Editor (English): HUANG Yuxin

- 中华海洋法学评论的其它文章

- BBNJ 环境影响评价规则、影响与因应