Cost-utility analysis of transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgery in severe aortic stenosis patients with intermediate surgical risk in Thailand

Unchalee Permsuwan, Voratima Yoodee, Wacin Buddhari, Nattawut Wongpraparut,Tasalak Thonghong, Sirichai Cheewatanakornkul, Krissada Meemook, Pranya Sakiyalak,Pongsanae Duangpakdee, Jirawit Yadee,

1. Department of Pharmaceutical Care, Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2. Center for Medical and Health Technology Assessment (CM-HTA), Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai,Thailand; 3. Pharmaceutical Care Training Center (PCTC), Faculty of Pharmacy, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai,Thailand; 4. Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University,Bangkok, Thailand; 5. Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 6. Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; 7. Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand; 8. Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 9. Division of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 10. Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla, Thailand

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) has been shown to provide comparable survival benefit and improvement in quality of life to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for treating patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) at intermediate surgical risk. This study aimed to evaluate the cost-utility of TAVI compared with SAVR for severe aortic stenosis with intermediate surgical risk in Thailand. METHODS A two-part constructed model was used to analyze lifetime costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) from societal and healthcare perspectives. The study cohort comprised severe AS patients at intermediate surgical risk with an average age of 80 years. The landmark trials were used to populate the model in terms of mortality and adverse event rates. All cost-related data and quality of life were based on Thai population. Costs and QALYs were discounted at 3% annually and presented as 2021 values. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated. Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted. RESULTS In comparison to SAVR, TAVI resulted in higher total cost (THB 1,717,132 [USD 52,415.51] vs. THB 893,524 [USD 27,274.84]) and higher QALYs (4.88 vs. 3.98) in a societal perspective. The estimated ICER was THB 906,937/QALY (USD 27,684.27/QALY). From a healthcare system perspective, TAVI also had higher total cost than SAVR (THB 1,573,751 [USD 48,038.79] vs. THB 726,342 [USD 22,171.63]) with similar QALYs gained to the societal perspective. The estimated ICER was THB 933,145/QALY (USD 933,145/QALY). TAVI was not cost-effective at the Thai willingness to pay (WTP) threshold of THB 160,000/QALY (USD 4,884/QALY). The results were sensitive to utility of either SAVR or TAVI treatment and cost of TAVI valve. CONCLUSION In patients with severe AS at intermediate surgical risk, TAVI is not a cost-effective strategy compared with SAVR at the WTP of THB 160,000/QALY (USD 4,884/QALY) from the perspectives of society and healthcare system.

Aortic stenosis (AS) represents a relevant public health problem, whose prevalence is expected to increase with population ageing.[1]Without aortic valve replacement,symptomatic severe AS carries a poor prognosis,with a two-year mortality nearing 50%.[2]Currently available options for the treatment of severe AS include surgical valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).[3]TAVI has been shown to be effective in treating patients with severe symptomatic AS who are inoperable and high-risk population for conventional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).[4-6]More recently,TAVI has been shown to provide comparable outcomes to SAVR, both in terms of survival[6,7]and quality of life,[8]for intermediate- risk patients as well.The intermediate-risk patients differ from the higher-risk population in several ways that may affect costs and outcomes. In particular, given that this population may be younger with fewer comorbidities, complication rates and length of hospital stay are likely to be different.

The adoption of TAVI is widespread among the Western world (i.e., the United States and Europe).[9]This is due to positive publications on clinical outcomes and cost-effective analyses in these countries,which had subsequently led to national reimbursement. Many of these healthcare systems, however,spend a significant portion of their GDP on healthcare.[10]In Thailand, TAVI has been performed in patients with severe AS since the first-in-human implantation in 2009.[11,12]Since then, it has been gradually performed in Thai AS patients, particularly in the hospitals located in Bangkok, the capital of Thailand. There are currently 5 TAVI valve brands available in Thailand. Those are: (1) Edwards Lifesciences (SAPIEN-3™), (2) Medtronic (CoreValve™ and Evolut RTM), (3) Boston Scientific (LOTUS Edge™and ACURATE neo™), (4) Abbott Vascular (Portico™), and 5) Vascular Innovation (Hydra™). The costs range between THB 500,000 and 1,000,000(USD 15,263-30,525).

Costly new medical devices, such as TAVI, together with the increasing elderly population and the COVID-19 pandemic has placed the sustainability of healthcare systems under severe economic pressure. Economic evidence has been used in many countries, including Thailand for decision makers to rationally allocate available healthcare resources.Health economic evaluation, such as cost-utility analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, has become an important tool to generate the useful economic evidence. According to the previous systematic review of cost-effectiveness analysis of TAVI,[13]only two Asian countries conducted three cost-effectiveness studies of TAVI in severe AS patients with either intermediate or high surgical risks.[14-16]Of those three studies, two studies were conducted in severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk. However,the findings were not in line between those studies.When compared to their respective willingness to pay (WTP) thresholds in each country, one study concluded that TAVI was cost-effective,[16]while the other reported that TAVI was not cost-effective.[15]Furthermore, TAVI resulted in a cost-effective strategy for severe AS patients with high surgical risk.[14]

In Thailand, the costly health technology, like medical devices, screening, or drugs needs evidence of economic evaluation and budget impact analysis to inform the coverage decisions of the benefits packages in the Universal Health Care Scheme (UHCS)or the National List of Essential Medicine (NLEM)[17]In addition, TAVI use in clinical practice is highly various between countries and correlated with national economic indicators leading to the need for country-specific analyses.[9]Hence, this study aimed to assess the cost-utility of TAVI compared with SAVR in the treatment of severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk.

METHODS

This study was conducted complied with the Thai Health Technology Assessment Guideline. The detailed information on the health technology assessment process for the development of health benefit package in Thailand were provided in the Supplement.[18,19]

Population

Our study population was severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk. Patients were considered to be at intermediate surgical risk on the basis of clinical assessments by a multidisciplinary heart team together with a risk model developed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) to estimate the risk of death at 30 days after surgery.[20]The intermediate surgical risk was defined as the STS scores of at least 4% to 8%; however, this range was not prespecified. Patients with an STS risk score of less than 4% would undergo TAVI if patients’ clinical characteristics were at risk for SAVR. The starting patient age was 80 years which reflected the general practice in Thailand.

Intervention and Comparator

The intervention in this study was TAVI with either Sapient valve or Medtronic valve. The access routes included both transfemoral (TF) or transapical(TA). Based on the information from cardiologists in expert meeting, above 90 percent of TAVI performed in Thailand used TF access route. The comparator in this study was SAVR.

Model Description

The analysis was based on a two-part constructed model, decision tree and Markov model, designed to represent the 30-day after undergoing the intervention and the long-term periods of time (Figure 1).The cohort population would undergo either SAVR or TAVI treatment. After receiving treatment, patients were alive or death within 30 days. Those who survived might be discharged without complication or had complications occurred within 30 days.The complications included within 30 days were acute major stroke and early complications. Early complications comprised acute kidney injury (AKI),major vascular complication, atrial fibrillation (AF),major bleeding, new permanent pacemaker. After the short-term decision tree model, patients would move to long-term Markov model which composed of no complication, acute major stroke, post stroke,complications, and death health states. Patients with no complication would enter no complication health state in the Markov model. Patients who had acute major stroke would enter post stroke health state.Those with early complications would move to such late complication health state in the Markov model.Acute major stroke or late complications would occur in the patients with no complication health state.A cycle length of one year was run in the Markov model with a life-time horizon. All patients eventually would be dead which was the absorbing health state.

Figure 1 A two-part constructed model. (A): Decision tree model for 30-day after undergoing the intervention; (B): Markov model for long-term complications.

Input Parameters

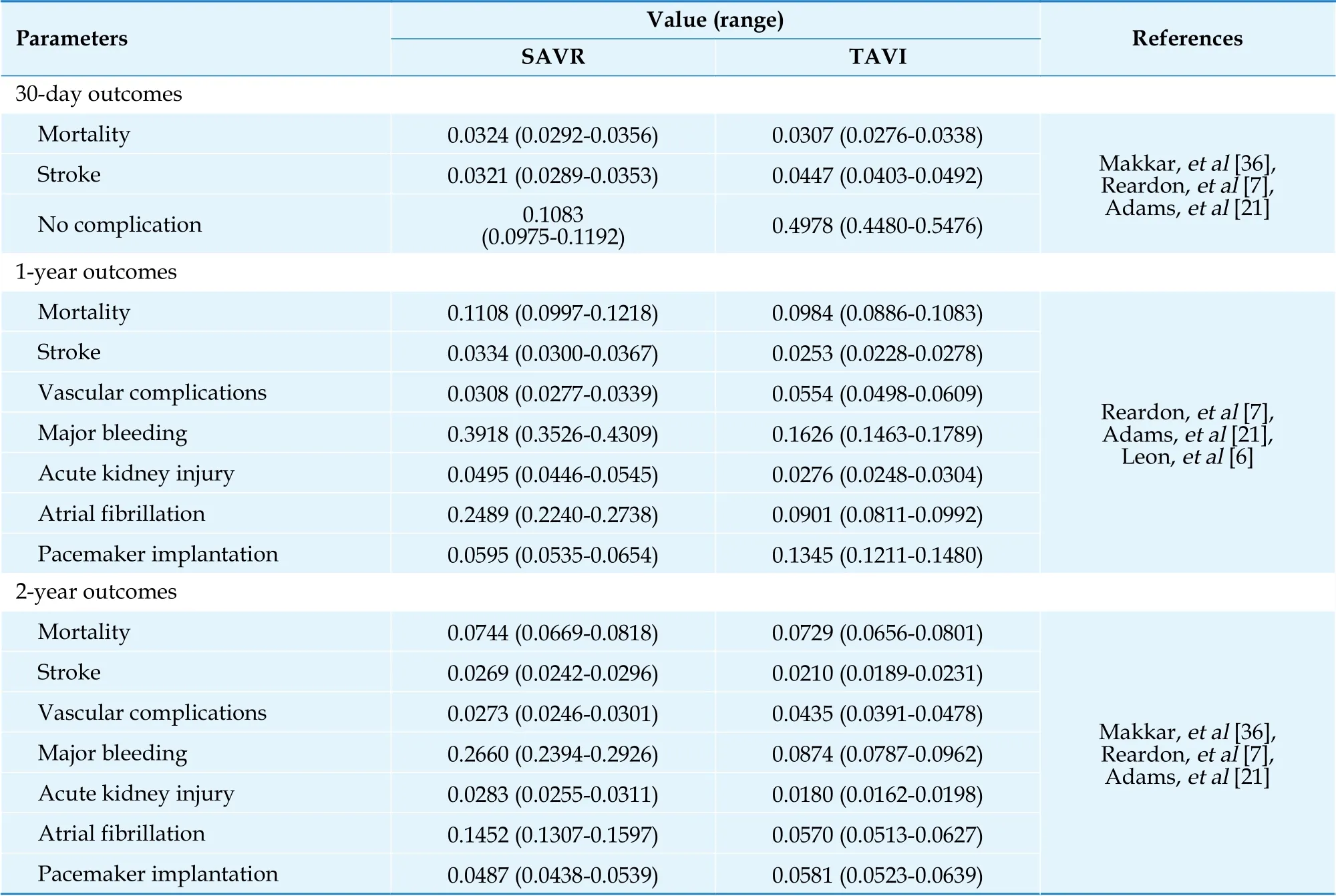

Transitional probabilitiesWe did a systematic search from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase since inception to July 2021. The searching terms were (“transcatheter aortic valve implantation” OR “transcatheter aortic valve replacement”)OR (Self-expanding OR balloon-expandable) AND“randomized controlled trial” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR randomized OR randomized OR “clinical trials”. The articles were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) study design was randomized controlled trial of TAVI compared with SAVR; (2) Outcomes were reported for severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk based on the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) 4%-8% or the logistic Euro-SCORE (LES) 10%-20%; (3) outcomes were reported at 30 days, 1 year, or longer than one year; (4) the study was conducted in human being; and (5) the study was published in English. The articles were excluded when other research designs, such as review article, letter to editor, etc. were used and TAVI did not compare with SAVR. The study process was shown in Supplement. Overall, three studies met aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included for analysis. Those were: (1) the Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve Trial Edwards SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve (Partner)trial (PARTNER 2);[6](2) surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients (SURTAVI);[7]and (3) Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Prosthesis(U.S CoreValve).[21]The events of all-cause death,acute major stroke, AF, AKI, major bleeding, new pacemaker, and vascular complications at 30 days,one-year, and two-years were pooled across studies using a meta-analysis. These pooled treatment effects were used as probability data in the constructed model (Table 1).

Table 1 Clinical input parameters: short-term and long-term outcomes following SAVR/TAVI.

The two-year probabilities were carried forwarded until the end of time horizon. We also applied the age-specific mortality rate (ASMR) of Thai general population from Ministry of Public Health,[22]and adjusted the ASMR by the risk of being severe AS into the analysis after two-year period. The odds ratio (95% confidence interval, CI) of one-year mortality of severe AS compared with no AS was equal to 2.57 (2.42 to 2.74).[23]

CostsIn general, TAVI can be performed at few large hospitals, particularly hospitals in Bangkok,the capital of Thailand. Of those large hospitals, two hospitals are located outside Bangkok. Since, the findings of this study would be presented to the SCBP as an important piece of economic evidence for policy recommendation to the NHSB following to the process mentioned above cost data were directly obtained from five large university affiliated hospitals.Three hospitals are located in Bangkok, one is in the North and the other is in the South of Thailand.

According to the perspective of society, costs included in this study were direct medical costs and direct non-medical costs. Indirect costs were not included due to avoid double counting of both the cost and the effect of the interventions for cost-utility analysis based on the Health Technology Assessment Guideline in Thailand.[24]Direct medical costs comprised costs of procedure and complication treatment which were retrieved from electronic database of hospitals. Direct non-medical costs, such as costs of transportation, food, accommodation, and caregivers, were collected from 134 severe AS patients who received TAVI or SAVR treatment from five hospitals. In addition, healthcare provider perspective was also considered in this study, only direct medical costs were included.

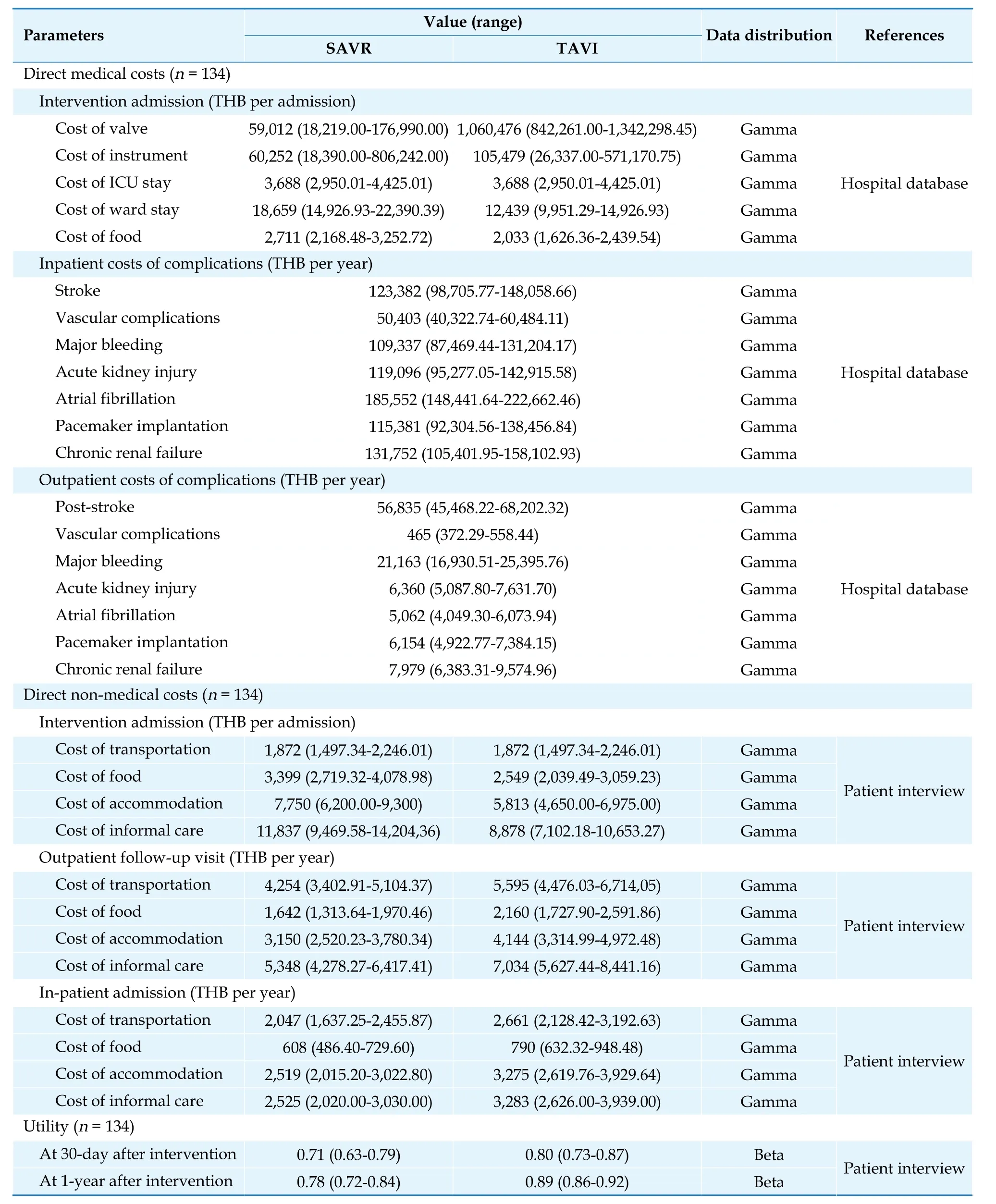

All cost data were adjusted for inflation based on the medical care section of Thailand’s consumer price index and presented in 2021[25]. The costs were converted into USD at a rate of 32.76 THB per USD,as of 17 November 2021[26]. All costs were shown in Table 2.

UtilitiesWe also collected utility data using the EQ-5D-5L Thai version from severe AS patients at three different time points, before undergoing the procedure (time 0). 30 days after procedure (time 1),and one year after procedure (time 2). Utility data were shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Costs and utility inputs.

Study outcomes

The outcomes of interest of this study were the lifetime total cost, life-years, quality-adjusted lifeyears (QALYs) which is the product of utility and life-year, clinical benefits in terms of overall cause of death, incremental costs, life-year gained, QALYs gained, and ICER.

Cost-utility Analysis

Base-case analysisThe lifetime total cost and outcomes of severe patients who received TAVI treatment compared with those who received SAVR treatment were estimated and discounted at an annual rate of 3%.[27]The difference in lifetime total cost divided by the difference in outcome for both strategies was calculated to estimate the ICER value. If the ICER falls below the accepted ceiling ratio in Thailand (THB 160,000/QALY or USD 4,884/QALY), which is about 1.2 times per capita gross national income (GNI) or about 133,037 THB in 2013,[28]TAVI treatment will be considered cost-effective.We also estimated the ICER from Healthcare system perspective by removing direct non-medical costs in the base-case analysis.

Sensitivity analysisA variety of deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed. A one-way sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the impact of the individual parameter uncertainties on the results. All variables such as transitional probabilities, costs, and utilities were varied within a specified range. If the standard deviation or standard error was available, we used it as range for analysis.When no such data were available, we would use the range of ± 10% for transition probabilities and ±20% for costs. The discount rate varied from 0 to 6%,following the recommendation of the Thai Health Technology Assessment Guideline.[27]The results are displayed as a tornado diagram. The cost of TAVI value was varied to determine the appropriate cost yielding an ICER of 160,000 THB/QALY. Scenario analyses were also performed by varying time horizons from lifetime to 5 and 10 years.

In addition, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA)was performed by allowing all input parameter values to vary simultaneously over their respective feasible ranges within the model.[29]A beta distribution was appropriate for transitional probability and utility data due to the range of 0-1. Gamma distribution was appropriate for cost data owing to the positive values. Based on the PSA, the simulation drew one value from each parameter distribution simultaneously and calculated cost and effectiveness pairs.This process was repeated a thousand times to provide a range of possible ICERs, given the specified probability distribution. Those ICERs were plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was also provided to illustrate the relationship between the WTP values and the probability of favoring each strategy.

RESULTS

Base-case Analysis

The results of the cost-utility analysis from the societal perspective demonstrated that TAVI treatment incurred a higher total cost (THB 1,717,132[USD 52,415.51]vs.THB 893,524 [USD 27,274.84])and gained more life-years (5.60vs.5.19) and QALYs(4.88vs.3.98) than SAVR treatment. This yielded an ICERs of THB 1,979,085/life-year (USD 60,411.62/life-year) and THB 906,937/QALY (USD 27,684.27/QALY). When considering healthcare system perspective, TAVI treatment had higher total cost than SAVR treatment (THB 1,573,751 [USD 48,038.79]vs.THB 726,342 [USD 22,171.63]) with similar gain in life-year and QALYs to the societal perspective. As a result, the estimated ICER was THB 933,145/QALY (USD 933,145/QALY) as shown in Table 3.

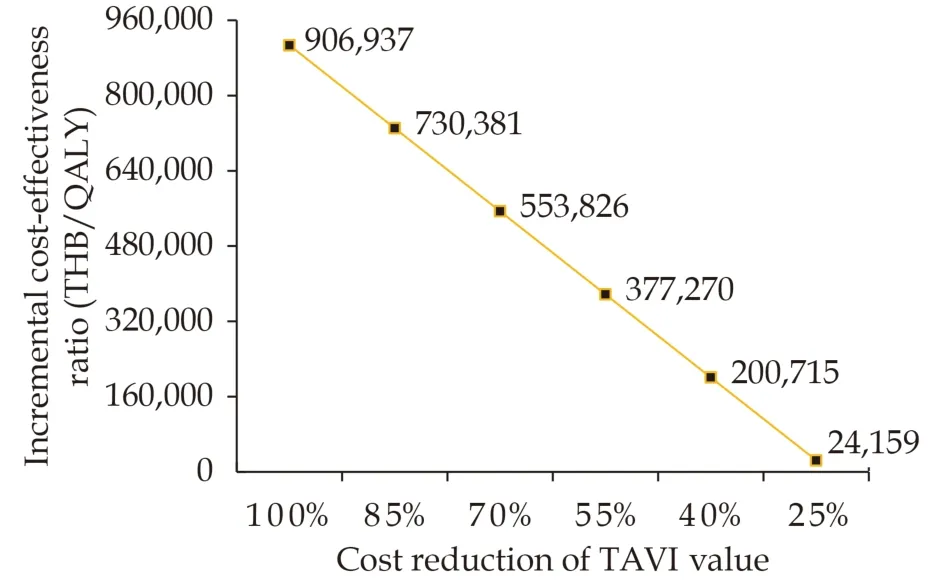

Sensitivity Analyses

The results of one-way SA using a tornado diagram indicated that utility of either SAVR or TAVI treatment and cost of TAVI valve were the top most influential parameters on the ICER estimate (Figure 2).The reduction in cost of TAVI valve resulted in a lower ICER. When cost of TAVI valve was reduced to THB 390,583 (USD 11,922.56), the ICER would be equal to the ceiling ratio of 160,000 THB/QALY (Figure 3).

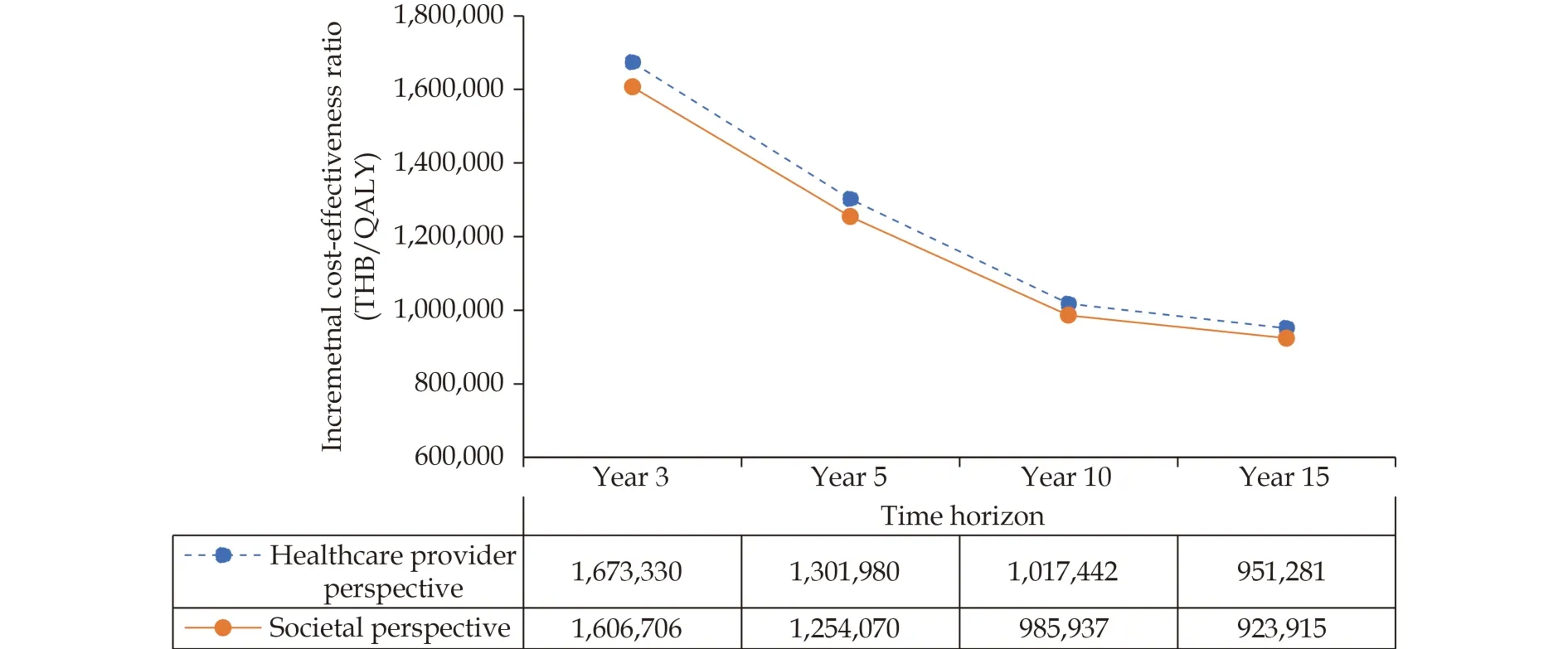

Figure 6 demonstrated the results of each scenario analysis. In all scenarios, TAVI treatment had a higher total cost and gained more LY and QALY than SAVR treatment. In terms of societal perspective, the ICERs of TAVI treatment compared with SAVR treatment over 5- and 10-year time horizons were THB 1,301,980/QALY (USD 39.742.99/QALY)and THB 1,017,442/QALY (USD 31,057.45/QALY),respectively. For healthcare provider perspective,the ICERs of TAVI treatment compared with SAVR treatment over 5- and 10-year time horizons were THB 1,254,070/QALY (USD 38,280.52/QALY) and THB 985,937/QALY (USD 30,095.74/QALY), respectively.

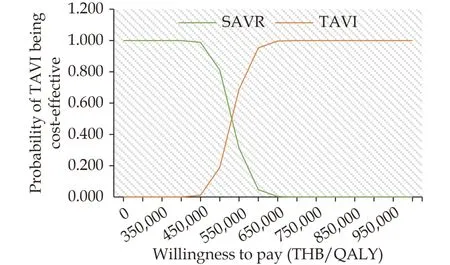

The scatter plot on the cost-effectiveness plane(Figure 4) demonstrated that all 1,000 iterations fell on the upper right quadrant. This signified that TAVI treatment was more costly and gained more QALYs than SAVR treatment. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve represents the probability of both treatment options at different WTP levels(Figure 5). When the level of WTP increased, TAVI treatment had a higher chance to be cost-effective treatment. At the WTP of 600,000 THB/QALY, the probability of TAVI being cost-effective treatment was about 95.3%.

Figure 2 Tornado diagram of TAVI compared with SAVR. IPD: inpatient department; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement;TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; THB: Thai baht; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

Figure 3 Threshold analysis varying cost of TAVI valve.QALY: quality-adjusted life-year; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; THB: Thai baht.

Figure 4 Scatter plots of 1,000 iterations for TAVI compared with SAVR on a cost-effectiveness plane. SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; THB: Thai baht.

Figure 5 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of TAVI compared with SAVR. QALY: quality-adjusted life-year; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation; THB: Thai baht.

Figure 6 Results from scenario analyses by varying time horizons. QALY: quality-adjusted life-year; THB: Thai baht.

DISCUSSION

This study was the first economic evaluation of TAVI treatment in severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk in Thailand. The clinical outcomes were based on the data from the PARTNER 2 clinical trial[6], the SURTAVI clinical trial,[7]and the U.S CoreValve clinical trial.[21]Costs and utilities were based on severe AS Thai patients. The estimated ICER was THB 906,937/QALY (USD 27,684.27/QALY). To justify whether the new intervention is cost-effective depends on the recommended WTP in each country. The findings of this study indicated

that TAVI is not a cost-effective treatment for severe AS patients with intermediate surgical risk at a ceiling ratio of THB 160,000/QALY (USD 4,884/QALY).The likelihood of being cost-effective treatment of TAVI became greater with an increase in WTP.

Eight cost-effectiveness studies in intermediate surgical risk of severe AS patients were conducted in Europe, America, Australia, and two countries in Asia (Japan and Singapore).[15,16,30-35]Of those studies, TAVI treatment was a dominant strategy,[32-34]indicating lower total cost with higher QALYs compared with SAVR, while three studies conducted in Canada (two studies) and Singapore (one study)showed the ICER below the WTP threshold of the country.[16,31,35]Only two studied conducted in Spain and Japan reported the ICER above the WTP threshold,[15,30]indicating that TAVI treatment was not likely to be cost-effective compared to SAVR treatment in patients with intermediate surgical risk for surgery. The reason was related to the high cost of the valve compared to the cost of hospitalization.The findings of this study were in line with that conducted in Spain and Japan. The TAVI valve in this study had about 18 times higher cost than the SAVR valve (TBH 1,060,476vs.THB 59,012). Although TAVI treatment had less hospitalization and cost of complications than SAVR treatment, those cost savings were not able to offset the costly TAVI valve. The cost reduction of TAVI valve is of great importance.

Defining an affordable benefit package at inception was crucial due to limited funding and the need to avoid patient co-pay. As technologies advance, a systematic, transparent and participatory process for defining a health benefit package helps policy makers to make appropriate decisions and ensure accountability of decisions. HTA is one step in the process to provide body of useful evidence for decision making.[18,19]

Clinical evidence has been shown the benefit of TAVI use in patients with severe symptomatic AS at intermediate surgical risk.[6-8]Expanding health benefit package for the UHCS reimbursement of TAVI use in this population needs body of HTA evidence to support. The findings of this study indicated that TAVI treatment is not a cost-effective strategy at the current price of TAVI valve in Thailand. Price negotiation might be necessary.

Several strengths and limitations should be taken into consideration in this study. First, although this study collected costs and utilities from severe AS patients who visited five large university affiliated hospitals, patients were not randomized to undergo TAVI or SAVR treatment. This might lead to some selection bias. We addressed this issue by thoroughly conducting sensitivity analyses. Direct non-medical costs showed insignificant impact on the estimated ICER. Utility values played quite a strong impact on the ICER. Our utility data were in line with those from other countries, which showed higher utility value for patients undergoing TAVI treatment compared with those undergoing SAVR.Second, there is a learning curve for the whole institution where the procedure is being done. Compared to western countries, TAVI treatment has been performed in patients with severe AS in Thailand since the first-in-human implantation in 2009. The TAVI procedure is performed both in the catherization laboratory with sedation and in the operating room under general anesthesia. When multidisciplinary cardiac teams have gained more experience and can perform TAVI procedure in the catherization laboratory for all hospitals in the future, it would decrease the cost of TAVI treatment and lower incidence of vascular complications.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that in patients with severe symptomatic AS at intermediate surgical risk, TAVI treatment is not a cost-effective strategy compared with SAVR at the WTP of THB 160,000/QALY (USD 4,884/QALY) from the perspectives of society and healthcare system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Health Systems Research Institute (Thailand). The funding source had no influence on the study design,data collection, data analysis and interpretation.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author contributions

UP initiated the study design and methodology.WB, NW, TT, SC, KM, PS, and PD participated in patient enrollment and data acquisition. JY and UP performed the data analysis. JY, VY and UP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2022年11期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2022年11期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Screening for hypertension-mediated organ damage and aetiology: still of value after 65 years of age?

- Effectiveness of sacubitril-varsartan versus angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: a retrospective cohort study of the RICA registry

- Systemic inflammatory markers in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- The relationship between serum miR-21 levels and left atrium dilation in elderly patients with essential hypertension

- Validating the accuracy of a multifunctional smartwatch sphygmomanometer to monitor blood pressure

- Small-molecule 7,8-dihydroxyflavone counteracts compensated and decompensated cardiac hypertrophy via AMPK activation