Germline BRCA2 variants in advanced pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A case report and review of literature

Cha Len Lee, Spring Holter, Ayelet Borgida, Anna Dodd, Stephanie Ramotar,Robert Grant, Kristy Wasson,Elena Elimova, Raymond W Jang, Malcolm Moore, Tae Kyoung Kim, Korosh Khalili, Carol-Anne Moulton,Steven Gallinger,Grainne M OKane, Jennifer J Knox

Abstract

Key Words: Pancreatic acinar carcinoma; BRCA; Polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitor;Case report

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) is a rare subtype of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 1%-2% of exocrine pancreatic neoplasms[1]. While there is some clinical and genotype difference, patients with PACC and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are often treated as one disease entity. Evolving data has increased our understanding of this rare tumor’s biology, treatment, and prognosis. Due to the disease’s rarity, most data about PACC are limited to reviews, case reports, and case series. The tumor biology of PACC is not well characterized due to the lack of tissue availability for large-scale molecular analysis. Intriguingly, data obtained in recent years have indicated that PACC has a distinctive mutational landscape[2-4]. There is increasing interest in this area, particularly regarding the homologous repair deficiency (HRD) signature in PACC. Chmieleckiet al[2] reported up to 45%deficiency of the DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway genes in the study population. Oncogenic therapeutic targets includingRAF1rearrangements and mismatch repair genes have proven elusive in a significant proportion of PACCs, and lack of tumor profiling probably contributes to low reporting[3,4].

Here, we present a PACC case to emphasize the clinical application of genomic profiling in the context of precision medicine for better patient outcomes. Although this patient was very unwell at the presentation, raising the question of suitability for modified FOLFIRINOX (mFFX), the knowledge of theBRCA2likely pathogenic variant (LPV) as predictive for mFFX sensitivity guided our decision to use this regime. In the case series section, we describe the clinical characteristics, therapeutic outcomes, and mutational signatures of additional 10 patients with PACC treated in our center. As proof of concept, we describe the immediate clinical impact for the patients with distinct genomic alterations that have been associated with sensitivity to specific chemotherapeutic or targeted agents.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

The patient was a 70 male smoker with recurrent lower limb joint pain and was generally unwell for the previous year.

History of present illness

He presented to a rheumatology service with joint pain, which was diagnosed as gout and treated with short courses of prednisolone; however, during the steroid treatment, he also experienced central abdominal discomfort, reduced appetite, and 10 kg weight loss. He had progressive lower joint pain with tender, warm skin nodules, which restricted mobility.

History of past illness

He had encephalitis and asthma as a child.

Personal and family history

He had a history of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis at age 46 for which he underwent a left total nephrectomy and a non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma at age 51, which was treated by lung resection. His mother died of ovarian cancer at age 72.

Physical examination

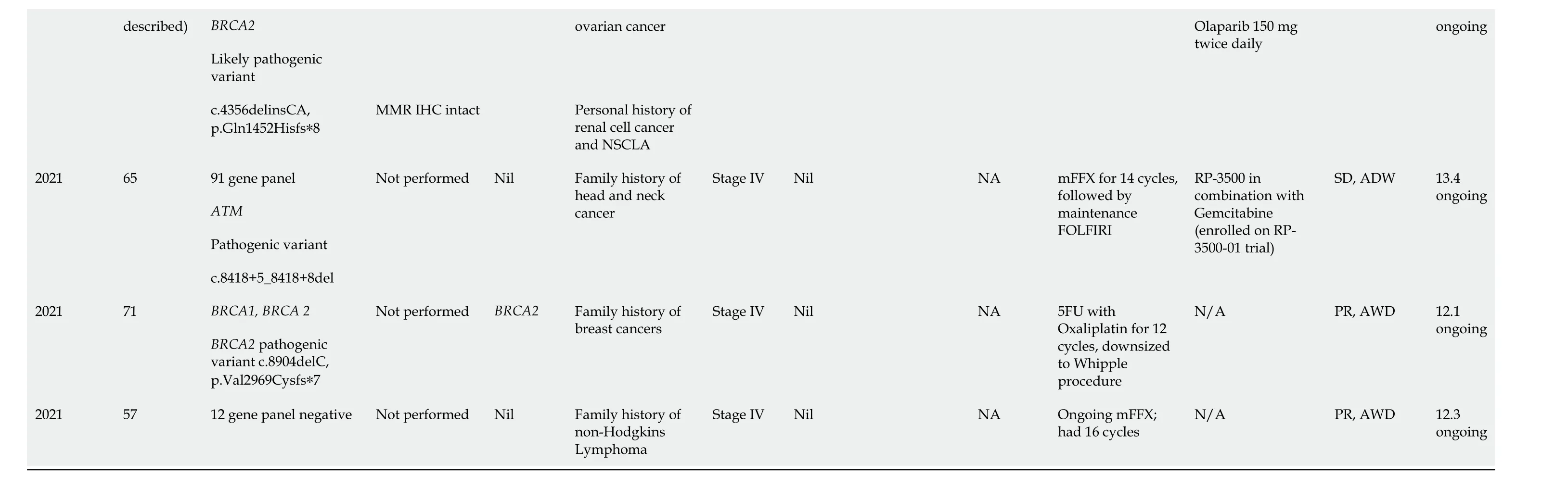

Physical examination revealed a cachectic man with a palpable liver edge and ill-defined widespread erythematous subcutaneous nodules on bilateral lower limbs (Figure 1A). Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) was 2.

Laboratory examinations

Initial blood tests demonstrated lipase > 6000 U/dL, elevated transaminases [alanine aminotransferase(ALT) 68 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase 58 U/L], total bilirubin 6 μmol/L, albumin 28 g/L and creatinine 120 μmol/L (estimated glomerular filtration rate 52 mL/min). Tumor markers were: Normal carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) 28 kU/L and raised alpha-fetoprotein 58 μg/L.

Imaging examinations

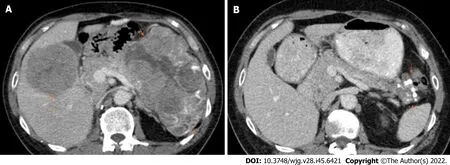

Initial computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a bulky pancreatic tumor measuring over 16 cm and multiple liver metastases. The largest liver lesion measured over 8 cm (Figure 2A). There was an illdefined area of sclerosis in the right ischium which was suspicious of metastasis. Whole-body bone scintigraphy detected mild non-specific increased activity in the right ischium corresponding to the area of sclerosis but no significant bony abnormality. CT chest showed no evidence of thoracic metastases.

FURTHER DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

The patient underwent a liver biopsy that confirmed a poorly differentiated carcinoma staining positive for keratin 7, CAM5.2, claudin 4, glypican 3, and A1AT. Negative markers included keratin 20, arginase 1, hepPar1, synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, and TTF1. The tumor was mismatch repair proficient.An additional skin biopsy of one of the subcutaneous nodules confirmed pancreatic lobular panniculitis.Germline testing identified aBRCA2LPV (c.4356delinsCA, p. Gln1452Hisfs*8).

CASE SERIES

Population and clinical data

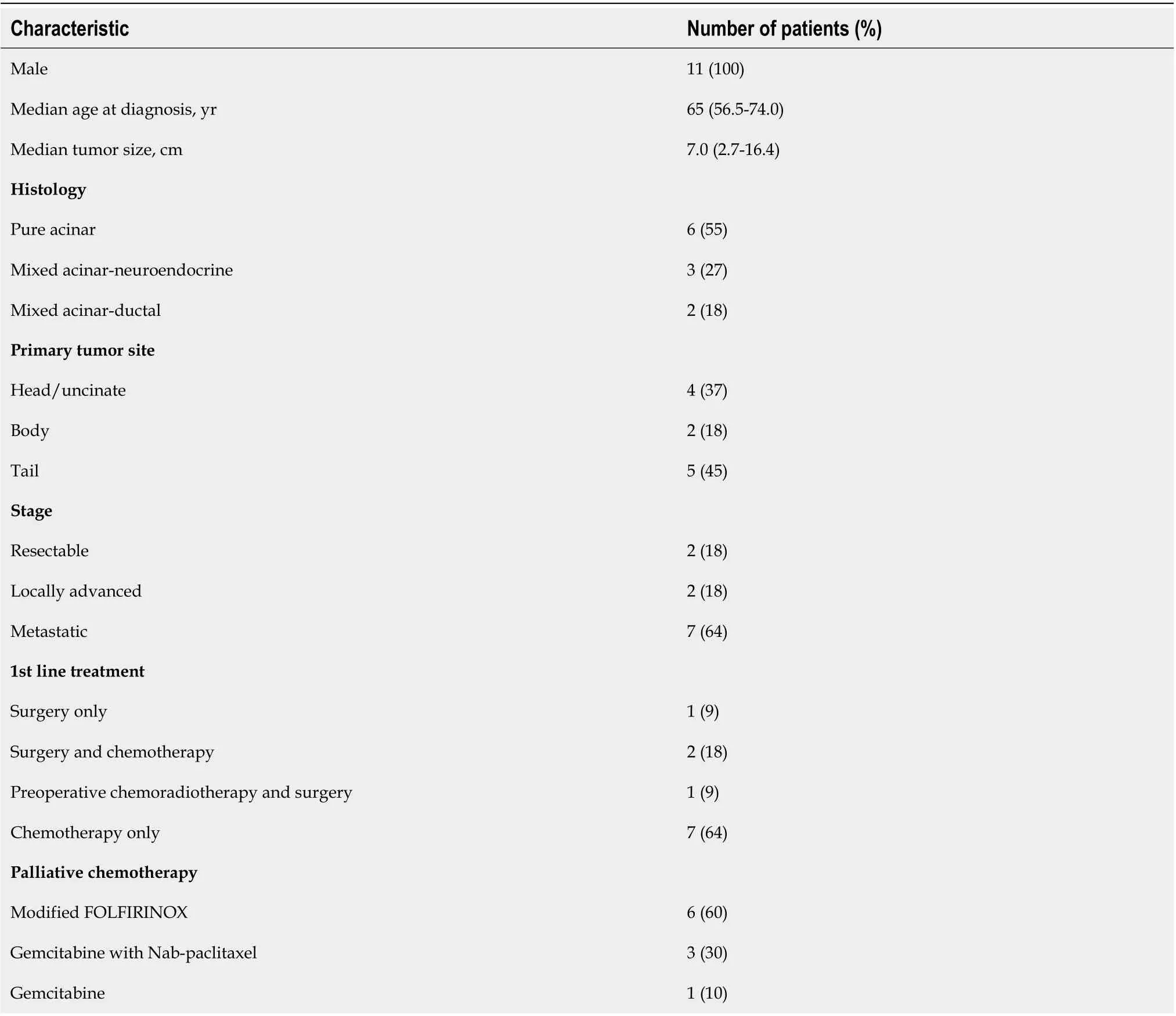

We treated 11 PACC patients between August 2014 and July 2021 at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre(PMCC), Toronto. These comprised 6 (55%) pure and 5 (45%) mixed PACC. Approximately 2000 pancreatic carcinoma patients were managed at PMCC during this period. The median age at diagnosis of the PACC patients was 65 years (range 57-74) and all were male. At diagnosis, 2 (18%) were resectable, 2 (18%) locally advanced, and 7 (64%) metastatic. The full demographic features of all patients are summarized in Table 1.

Four (36%) patients had curative-intent surgery. Three of them developed systemic relapse and received subsequent treatment with palliative chemotherapy. All seven metastatic patients had chemotherapy. Altogether, ten patients received palliative chemotherapy: mFFX (6), Gemcitabine plus Nab-paclitaxel (GnP) (3), and Gemcitabine (1).

The median time to progression from the date of surgery to the first systemic relapse for the resected patients was 10.5 mo (1.5-10.6). After a follow-up period of 20.4 mo, 6 (55%) patients had died of the disease while five are still alive. The median overall survival (OS) of the cohort was 20.4 mo (range 4.6-36.0) but this variable is temporally immature. The median OS of the four resected patients was 30.3 mo(28.2-36.0).

Genomic data

Eligibility for germline genetic testing in Ontario has evolved with the advent of next-generation sequencing, newly identified genes, and the association of established genes with different cancer types.In April 2021, Ontario Health expanded the availability of germline testing to all individuals with pancreatic cancer regardless of age or family history[5]. Before this, germline testing for individuals with pancreatic cancer was based on personal and family history as well as the age of onset. The gene(s)or multi-gene panels performed for patients are based on the individuals’ personal and family history at the time of the initial genetic counseling.

Table 1 Clinicohistopathologic features of the pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma patients in this dataset (n = 11)

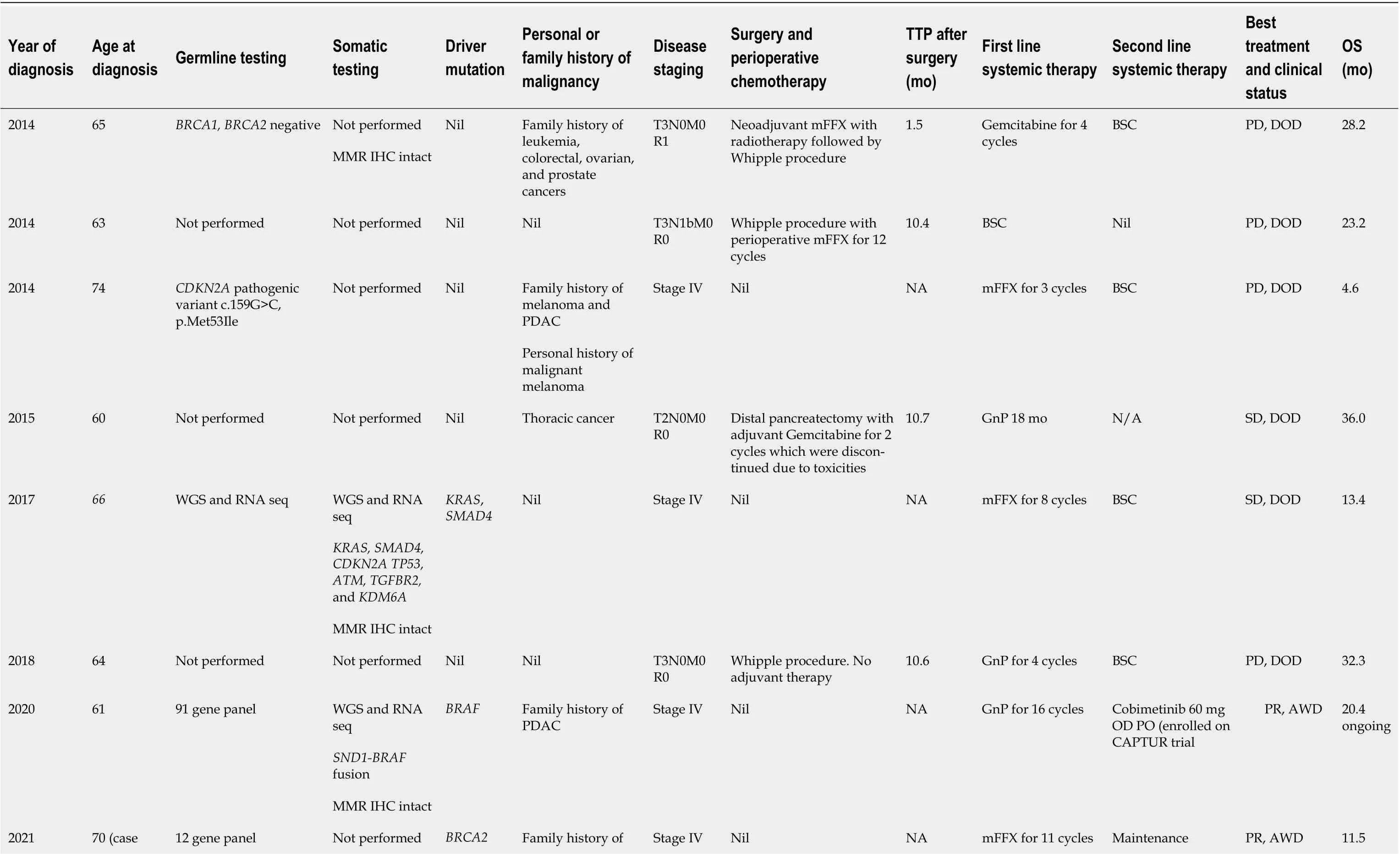

Seven patients in our case series had clinical germline testing. Four patients did not have germline testing, as they did not meet eligibility criteria based on family history at the time of their diagnosis.Germline PV/LPV was identified in four patients [2BRCA2(18%),1ATM(9%), 1CDKN2A(9%)]. Two(18%) patients had somatic testing with whole-genome sequencing and RNA sequencing as part of clinical trial participation. Identified somatic variants were SND1-BRAFfusion in one patient andKRAS,SMAD4,CDKN2A,ATM,TP53,TGFBR2, andKDM6Ain another patient.

In terms of actionability, we identified two patients withBRCA2PV/LPV (18%) and oneSND1-BRAFfusion (9%). The first patient carrying a germlineBRCA2LPV is described in this case report. The second patient carrying a germlineBRCA2PV had advanced acinar neuroendocrine carcinoma. Briefly,he was commenced on a combination of 5 FU and Oxaliplatin with a dose reduction (30%) due to comorbidities. Despite this, the evaluation CT scan following 8 cycles of chemotherapy showed a partial response of the primary tumor (63% smaller than baseline) as per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1. He continued additional 4 cycles with further tumor regression, followed by resection. The tumor was pathologic near complete treatment response.

The patient harboring anSND1-BRAFfusion was commenced on first line GnP. The evaluation CT scans following 6 cycles of chemotherapy showed a significant partial response (55% decrease than baseline) of the primary tumor and lymph nodes as per RECIST1.1. After 16 cycles of GnP, he developed progressive disease and was switched to single-agent Cobimetinib as part of clinical trial participation.Molecular profiling was negative for other key driver mutationsKRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, SMAD4, andBRCAin this patient. Full mutational profiles of the patients and treatment history are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2 Germline and somatic molecular profiles of the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients in this study

TTP: Time to progression; OS: Overall survival; MMR IHC: Mismatch repair immunohistochemistry; mFFX: Modified FOLFIRINOX; GnP: Gemcitabine with Nab-paclitaxel; BSC: Best supportive care; PD: Progressive disease; DOD:Dead of disease; SD: Stable disease; PR: Partial response; AWD: Alive with the disease; WGS: Whole genome sequencing; RNA seq: RNA sequencing; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; NSCLA: Non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

These findings were compatible with PACC with panniculitis, hepatic metastases, and indeterminate bony involvement. Histology revealed no concurrent existence of ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine or mixed tumor of the pancreas.

TREATMENT

The initial plan was to treat the patient with GnP in consideration of his poor PS. However, this decision was changed to the mFFX regimen following the documentation of the germlineBRCA2LPV. mFFX was administered every 2-wk with an additional 20% dose reduction of Oxaliplatin and Irinotecan(Oxaliplatin 65 mg/m2, Irinotecan 120 mg/m2, Fluorouracil 4200 mg/m2and Folinic acid 400 mg/m2).The chemotherapy calculations were based on a body surface area of 1.77 m2.

Figure 1 Panniculitis is a skin manifestation that can be detected in up to 45% of patients before the recognition of pancreatic disease. A:The widespread ill-defined erythematous tender skin nodules and/or plaques that develop on the shins and around the ankles of our patient as the initial clinical presentation; B: Complete resolution of the panniculitis in our patient after 4 cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX, suggestive of early clinical response.

Figure 2 Comparison of serial computed tomography images of our patient during chemotherapy. A: Initial axial post-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan shows a large heterogeneous solid mass in the pancreatic tail (short arrows) and a hypoattenuating metastatic liver mass (long arrow); B:Post-chemotherapy axial CT scan performed after 11 cycles of chemotherapy demonstrates marked interval reduction in the size of the pancreatic mass (arrows) and metastatic liver mass (not visible in this image).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After the first cycle of mFFX, the patient was hospitalized due to fever, confusion, and worsening polyarthritis. A full septic screen revealed no clear infectious etiology. CT brain showed no brain abnormality. X-rays of several joint areas including sacroiliac joints showed no radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis or septic arthritis. A left knee joint aspiration revealed an inflammatory synovial fluid with elevated white blood cell count, but no growth of infectious organisms and negative for crystal arthropathy. Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide levels were negative. The rheumatology team believed the patient’s inflammatory seronegative arthritis was paraneoplastic in nature. The patient also displayed clinical adverse events consistent with steroid-induced psychosis, due to the concurrent prednisolone and dexamethasone use. He was started on Naproxen with a tapering dose of prednisolone (from 15 mg daily). His condition improved within a week time and chemotherapy was resumed. Two months after starting mFFX, CT evaluation (post 4 cycles of chemotherapy)showed a 56% partial response based on RECIST1.1. The patient had a marked improvement in symptomatology and panniculitis (Figure 1B). His PS also improved to 0. He continued to tolerate mFFX with grade 1 peripheral sensory neuropathy of hands and feet. Another CT (post 8 cycles of chemotherapy)showed further tumor shrinkage in the primary tumor and hepatic metastases. The sclerotic bone lesion was unchanged in the interval. As the patient was getting a deepening partial response and tolerating mFFX, the chemotherapy was repeated for a total of 11 cycles. A CT imaging at that time point showed further tumor regression in the pancreatic tumor and the hepatic metastases, totaling a 70% decrease from baseline (Figure 2B). The biochemical response was also seen with a CA19-9 level of 17 kU/L.

After 11 cycles of mFFX, we decided to stop chemotherapy due to the accumulative neurotoxicity.Considering the germlineBRCA2LPV, we elected a therapeutic switch to Olaparib, a polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitor (PARPi), as maintenance therapy. He was started on Olaparib 150 mg twice daily dosing that was adjusted for his renal function. At the time of this writing, the patient experienced disease stability for 5 mo with Olaparib, which is ongoing. He tolerates Olaparib with grade 1 fatigue but has no major side effects. He is on monthly follow-ups.

DISCUSSION

PACC typically presents in the younger population with a median age of 62 years old. It is more frequent in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.3:1[6-8]. The majority (50%-60%) present at an advanced stage, with a median tumor size of 7 cm, and lesions smaller than 2 cm are rarely detected[6-10]. Some cases present with mixed differentiation including mixed acinar-ductal and mixed acinarneuroendocrine subtypes. As the tumor is predominantly found in the tail of the pancreas, patients do not usually present with biliary obstruction, and elevation of CA19-9 is not typically seen[3,11].However, there have been reports of elevated alpha-fetoprotein in younger patients[7,8]. In extreme cases, up to 10%, of patients have lipase hypersecretion which leads to systemic fat necrosis with eosinophilia, erythematous subcutaneous nodules, and polyarthralgia[6,7,9,10]. This paraneoplastic syndrome,also known as Schmid’s triad, is often associated with a poor prognosis[12-15]. The prognosis of PACC is slightly better than that for PDAC[6]. In comparison, 5-year OS for PACC was 42.8%vsPDAC 3.8%[16]. In this study, we analyzed the full clinical characteristics, therapeutic outcomes, and mutational signatures of 11 patients with PACC treated at our center. Based on our analysis, the median OS across all stages is 20.4 mo and 30.3 mo among the resected patients.

Available literature suggests that over one-third of PACC patients harbor potentially druggable alterations such asBRCA2, PALB2, ATM,BRAF,andJAK1[17]. We observed only one PACC with somaticKRASmutation (9%). This result may be limited by the incomplete somatic testing rate in this study. In distinction to PDAC which is associated withKRASdriver mutations in more than 93% of cases,KRASmutations occur at a much lower prevalence in the acinar/mixed neuroendocrine tumor(9%)[18-21]. While it is difficult to generalize as pancreatic carcinoma is a complex heterogeneous disease, a strong argument can be made that the lack of mutatedKRASidentifies a cohort rich in targetable alterations including fusions, and should have access to integrative germline and somatic sequencing[22].

Multiple studies including a large series reported by Chmieleckiet al[2] involving 44 PACCs reported a 45% deficiency of DDR pathway genes[3,4,23]. These are inclusive of deficiencies in theBRCApathway and mismatch repair. Combined results suggested that approximately 23% of PACCs are enriched with fusion rearrangements involvingBRAForRAF1genes[2,19]. It appears that PACC subgroups that are lackingRAF1rearrangements (i.e.,fusion-negative tumors) were significantly enriched for deficiency in HRD, and both tumor types are mutually exclusive[2]. Conceptually, these“fusion-negative” tumors can serve as a beneficial demarcation in over two-thirds of PACC patients who may be candidates for platinum-based chemotherapy. PACC withBRCA1/2variants have greater sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy and demonstrate significantly better OS than when treated with non-platinum agents[24]. Platinum chemotherapy drugs exert their cytotoxic effect by binding directly to DNA, causing crosslinking of DNA strands and thereby inducing DNA double-strand breaks, which also are ineffectively repaired in cells lacking functioningBRCA1/2. Both the patients in our case series with germlineBRCA2PV/LPV had substantial radiographic regression despite dose reduced Oxaliplatin. Although our patient described in the case report was very unwell with poor PS at presentation, raising the question of suitability for mFFX, the knowledge of theBRCA2LPV as predictive for platinum sensitivity guided our decision to use this regime and resulted in his improved outcome. The other patient was successfully downsized to enable the Whipple procedure for curative intent. Notably, we identified one patient withSND1-BRAFkinase fusion in our case series. Germline and somatic testing were negative forBRCA1orBRCA2in this patient. This particular variant fusion joinsSND1exons 1-10 withBRAFexons 11-18 and maintains the reading frame. It is worth noting that this particular configuration is the most prevalent gene fusion described in melanoma, thyroid, and lung cancers. It has also been reported in PACC[2]. This novel fusion is potentially targetable with MEK inhibitors, such as Trametinib and Cobimetinib[2,25].

Germline testing and tumor sequencing results are invaluable in identifying PACC patients for treatment regime determination and predictive biomarkers for investigational targeted therapies[14,22,23,26,27]. Newly diagnosed patients with PACC should undergo germline genetic testing and somatic profiling where appropriate, given the high frequency of pathogenic germlineBRCAalterations in PACC. This should be made available to patients regardless of clinical presentation, the pattern of metastases, and pre-existing co-morbidities. This is also consistent with NCCN American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines which recommend all PDAC patients have upfront germline testing as part of the evolving precision strategy and screening strategies[28]. Similar to numerous studies, our patients with pathogenicBRCA1/2variants have an increased risk of pancreatic, ovarian, breast, and other cancers (Table 2). The lifetime risk for pancreatic cancer inBRCA1andBRCA2mutant carriers is 1% and 4.9%, respectively[29,30]. Unlike breast and ovarian cancers, germlineBRCA1/2mutations alone do not pose a significant risk of pancreatic cancers. Recent literature review showsBRCA2confer to 5%-17% of familial pancreatic cancers (FPC) andBRCA1is not as highly prevalent[31-34]. Studies show that germline susceptibility gene mutations were not found in 80% of pancreatic cancer individuals with strong family history[31,35]. Therefore, comprehensive genome sequencing is needed to identify new possible deleterious genes associated with FPC.

There are no current clinical practice algorithms for PACC, and it is treated in the same way as PDAC. Although FOLFIRINOX represents the standard treatment with the highest efficacy in PDAC, it is not well studied in PACC[36]. Since 2010, there is a recognized OS benefit to platinum-based agents compared to Gemcitabine or Capecitabine-based regimens, and current therapeutic approaches of metastatic PACCs utilize more FOLFOX or FOLFIRINOX. Furukawaet al[37] described a PACC patient with aBRCA2PV who received Cisplatin after a recurrence of liver metastasis and had a complete remission of the recurring tumor. Ploquinet al[38] reported a PACC patient with aBRCA2PV who experienced a 14-year complete remission following nine cycles of GEMOX, without surgical intervention. Therefore, Cisplatin and GEMOX may be alternatives in patients harboring deficiencies in DDR genes who are unfit for FOLFIRINOX.

Due to accumulative neurotoxicity after 11 cycles of mFFX, our patient decided to stop systemic chemotherapy completely and de-escalated to Olaparib as a maintenance approach. The use of PARPi in PACC patients with germlineBRCA1orBRCA2PV/LPV is anecdotal[2,23,26]. Furthermore, the updated analysis of the POLO trial showed a lack of OS benefit and quality of life improvement in their Olaparib-treated patients compared to the placebo arm[39]. Despite the aforementioned, we believe that metastatic PACC patients with confirmed HRD phenotype and demonstrated strictly defined platinum sensitivity that involved exceptional response after 16 wk of chemotherapy should be considered for the benefit of PARPi, as the case described.

Like PDAC, surgery offers the best treatment approach for improved long-term survival[11,16,40].The combination of surgical approach and perioperative chemotherapy in PACC is mainly adapted from the PDAC practice[40-42]. As mentioned, our patient with metastatic germlineBRCA2PV had remarkable tumor downstaging following mFFX, underwent curative surgery, and achieved a pathologic near complete treatment response. Optimizing treatment approaches from this standpoint,with growing access to germline and somatic profiling, should also be further explored in PACC.

CONCLUSION

Although it is a rare disease, it is important to identify both common and rare actionable variants in PACCs. In PACC patients withBRCAvariants, the maintenance treatment of PARPi after effective platinum-based chemotherapy should be explored further. Surgical resection may provide the chance of cure after induction chemotherapy in very well-selected patients, particularly in patients withBRCAvariants. Further large-scale studies are required to verify these therapeutic strategies for PACC patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledged Dr. Thiago Muniz’s contribution to reviewing this manuscript for grammar and syntax.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Lee CL contributed to the data investigation, writing, and editing of the original draft; Holter S participated in the genomics data curation and revision of the final manuscript; Borgida A, Dodd A and Ramotar S involved in the data acquisition and curation; Kim TY and Khalili K participated in the radiological investigation;Grant R, Elimova E, Wasson K, Jang RW, Moore M, and Moulton CA read and approved the final manuscript;Gallinger S and O’Kane GM reviewed and edited the manuscript; Knox JJ supervised the project and final manuscript revision.

Informed consent statement:Informed consent is obtained from all participants. Written informed consent is obtained from the patient to publish the case report and accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Canada

ORCID number:Cha Len Lee 0000-0002-3919-7539.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年45期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年45期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Rifabutin as salvage therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: Cornerstones and novelties

- Meta-analysis on the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in China

- Endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for sessile colorectal polyps sized 10-20 mm

- Best therapy for the easiest to treat hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected patients

- Deep learning based radiomics for gastrointestinal cancer diagnosis and treatment: A minireview

- The mononuclear phagocyte system in hepatocellular carcinoma