Growing importance of urogenital candidiasis in individuals with diabetes: A narrative review

Jasminka Talapko, Tomislav Meštrović, Ivana Škrlec

Jasminka Talapko, Laboratory for Microbiology, Faculty of Dental Medicine and Health, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Osijek 31000, Croatia

Tomislav Meštrović, University North, University Centre Varaždin, Varaždin 42000, Croatia

Tomislav Meštrović, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Department for Health Metrics Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington 98195, United States

lvana Škrlec, Department of Biophysics, Biology, and Chemistry, Faculty of Dental Medicine and Health, J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Osijek 31000, Croatia

Abstract Both diabetes and fungal infections contribute significantly to the global disease burden, with increasing trends seen in most developed and developing countries during recent decades. This is reflected in urogenital infections caused by Candida species that are becoming ever more pervasive in diabetic patients, particularly those that present with unsatisfactory glycemic control. In addition, a relatively new group of anti-hyperglycemic drugs, known as sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, has been linked with an increased risk for colonization of the urogenital region with Candida spp., which can subsequently lead to an infectious process. In this review paper, we have highlighted notable virulence factors of Candida species (with an emphasis on Candida albicans) and shown how the interplay of many pathophysiological factors can give rise to vulvovaginal candidiasis, potentially complicated with recurrences and dire pregnancy outcomes. We have also addressed an increased risk of candiduria and urinary tract infections caused by species of Candida in females and males with diabetes, further highlighting possible complications such as emphysematous cystitis as well as the risk for the development of balanitis and balanoposthitis in (primarily uncircumcised) males. With a steadily increasing global burden of diabetes, urogenital mycotic infections will undoubtedly become more prevalent in the future; hence, there is a need for an evidence-based approach from both clinical and public health perspectives.

Key Words: Balanitis; Balanoposthitis; Candida; Candidiasis; Diabetes; Pregnancy; Urogenital infections; Vulvovaginitis

lNTRODUCTlON

Diabetes is a salient global health issue, with an enormous disease burden that has increased substantially in recent decades for the majority of developed and developing countries. The estimations from the International Diabetes Federation reveal that 537 million adults are living with diabetes around the world, with a projected growth to 693 million or more by 2045 without effective preventative methods[1,2]. On the other hand, the estimates from the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections show that every year there are over 300 million individuals of all ages suffering from a fungal infection that can seriously impact their health[3], which also includes urogenital infections caused by yeasts belonging to the genusCandida.

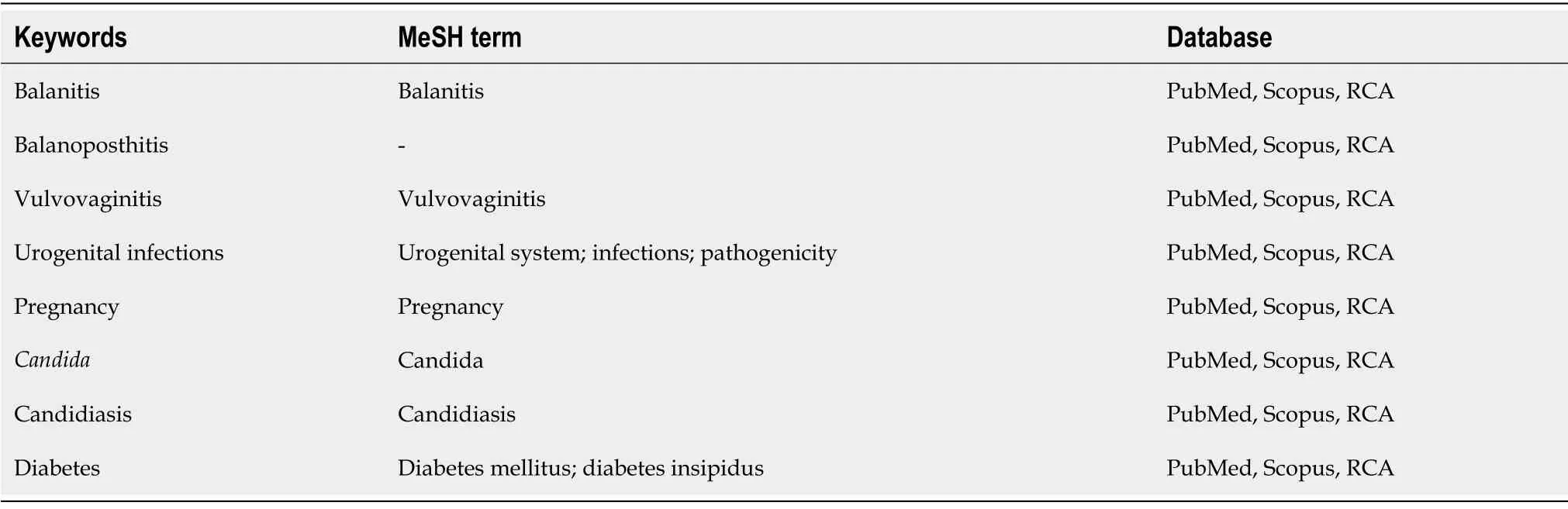

Taking into account such considerable global prevalence of these two frequently coexistent clinical conditions, it is of no wonder that diabetic patients with genitourinary candidiasis are currently pervasive not only in primary practice but also in secondary and tertiary care facilities. In addition, a relatively new group of anti-hyperglycemic drugs known as sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors made both females and males more prone toCandidacolonization of the urogenital region as well as for subsequent infection[4-6]. All of this means urogenitalCandidainfections may become even more ubiquitous among diabetic patients in the future. Therefore, given the scarcity of recent and comprehensive sources that provide an integrative and critical overview of the available literature on this topic (Table 1), in this review we aimed to summarize microbiological, pathophysiological, and clinical facets of urogenital infections withCandidaspecies in both females and males with diabetes.

Table 1 Keywords, database, and search time

DlABETES AND lMMUNE RESPONSE AGAlNST lNFECTlONS

According to the classification published by the American Diabetes Association, diabetes occurs in four basic forms, of which diabetes mellitus type 1 and diabetes mellitus type 2 are the most common forms of the disease[7]. In the quotidian clinical approach, fasting blood glucose levels up to 5.6 mmol/L are normal. When these values are above 7 mmol/L, this represents a key criterion for diagnosing diabetes mellitus, while values between 5.6 mmol/L and 6.9 mmol/L indicate prediabetes[8]. Therefore, it is always necessary to perform two glucose measurements: the first one on an empty stomach; and the second 1-2 h after a meal. Glucose values 2 h after a meal should fall below 7.8 mmol/L; if these values are still above 11 mmol/L, then we can diagnose diabetes mellitus with a substantial amount of certainty. If these values are between 7.8 to 11 mmol/L, we consider prediabetes or glucose intolerance[9]. The vital difference between prediabetes and diabetes is that prediabetes can be reversed. Of course, the most crucial factors are lifestyle changes, but there are also several viable pharmacological approaches.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus is caused by an absolute (or almost absolute) lack of insulin due to autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells, which leads to insulin insufficiency and hyperglycemia[10]. Conversely, type 2 diabetes mellitus is characterized by insulin resistance with an inadequately compensatory increase in insulin secretion[11]. Gestational diabetes occurs in pregnancy, most often during the second trimester of pregnancy. Insulin resistance is potentiated by hormones produced by the placenta[12]; therefore, it occurs in females whose pancreatic function does not overcome pregnancy-related insulin resistance. The main consequences are increased risks of preeclampsia, macrosomia, as well as Cesarean delivery and their associated morbidities[13].

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common endocrine disorders characterized by a disorder in insulin secretion and its action. Due to its frequency, it is currently a global health problem[14]. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is constantly increasing in developed and developing countries alike. According to the data from 2017, its prevalence is around 8.8% worldwide[15]. In addition to a myriad of co-occurring problems characteristic of patients with diabetes mellitus, a particular issue is immune system dysfunction resulting from complex interactions between the endocrine and immune systems[16]. Immune dysfunction occurs due to elevated insulin levels (hyperglycemia) and leptin present in affected individuals, resulting in an increased risk of various organ damage[17].

Decreased immunity is manifested in decreased T lymphocyte count, reduced cytokine release, increased programmed leukocyte cell death, reduced neutrophil function, impaired ability to fight infectious agents, and increased susceptibility to infection[14]. The increased risk of opportunistic infections is a particular problem due to the weakened ability to fight invasive pathogens[18]. In patients with diabetes mellitus, the recovery time after infection is significantly prolonged compared to individuals without it[19]. One of the salient indicators that should raise a suspicion of underlying diabetes is a propensity for recurrent infections caused by opportunistic pathogenic fungal species belonging to the genusCandida[20]. The pathogenic abilities ofCandidaspecies and their colonization factors depend on host-related immune factors due to the intricate homeostatic relationship of fungi with the host’s current immune status, a key determinant of commensalism or parasitism[21]. From a pathophysiological perspective, we find a suitable environment in diabetic patients forCandidamultiplication and proliferation due to alteration of gut microbiota, dietary changes, reduced intestinal secretions and altered liver function, continued usage of antimicrobial agents (and other drugs), coexisting diseases, as well as the pervasive deficiency of key nutrients, as demonstrated in the literature[21].

CANDlDA AS A PARAMOUNT FUNGAL PATHOGEN

The profile of Candida albicans and non-albicans Candida species

Fungal infections caused byCandidaspecies lead to a significant health burden, causing high mortality rates, hospitalizations, and increased treatment costs[22]. Lethal outcomes are most commonly seen as a result of sepsis and invasive systemic candidiasis[23].

Candida albicanswas the most widespread fungal pathogen isolated during episodes of candidiasis for a long time. Still, recent literature reports reveal an increasingly important role of other non-albicansspecies such asCandida glabrata(C. glabrata),Candida parapsilosis(C. parapsilosis),Candida krusei(C. krusei),Candida tropicalis(C. tropicalis), and more recentlyCandida auris(C. auris)[24]. However, the most commonly isolatedCandidaspp. from clinical specimens are non-albicansspecies. These other nonalbicans Candidaspecies are becoming more noticeable due to the production of virulence factors that were once attributed exclusively toC. albicans; furthermore, they are also characterized by reduced sensitivity to the most commonly used antifungal drugs[25]. The prevalence and virulence of nonalbicans Candidaspecies show varied geographical distribution, but more importantly many non-albicans Candidaspecies cause more frequent fungal infections in patients with diabetes. That is especially pertinent for patients with type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus with foot ulcers and skin and nail lesions[6]. Considering all of the above, species-level identification ofCandidaspp. should be introduced into routine laboratory work-up[26].

But notwithstanding such global prominence of non-albicanscandida,C. albicansis still the most common cause of candidiasis[27]. It can be a colonizer of skin and many mucosal surfaces and can thus easily act as an opportunistic pathogen in the genitourinary system[28]. Approximately 75% of females have at least one episode of vulvovaginal candidiasis during their lifetime, and the most common cause (i.e.in 90% of cases) the putative species isC. albicans[29]. According to available data, in females with diabetes mellitus who presented with a vulvovaginal infection caused byCandida,C. albicansis the most prevalent fungus in over 50% of cases, while different non-albicans Candidaspecies are present in about 40% of cases[30].

Candidais a polymorphic fungus that, contingent on the environment in which it is located, can alter its morphology from yeast form (blastoconidia) to pseudohyphae and hyphae[31]. Indeed, this is one of the most important differences from otherCandidaspecies because it can create true hyphaein vivowhen met with favorable conditions[32]. Two serotypes ofC. albicanshave been identified, namely type A and type B[33], and numerous factors contribute to the noticeable increase in invasive fungal infections, including hyperglycemia[19].

Major virulence factors in C. albicans

Virulence represents the ability of a microorganism to damage a host[34], andC. albicanspossesses a panoply of virulence factors[35]. One of the most important factors is dimorphism (already mentioned), which represents the ability ofC. albicansto change its shape from yeast to mold, with subsequent formation of true hyphae under favorable conditions. The latter trait significantly increases its invasiveness and proteolytic activity; however, in yeast form, it shows the propensity for greater dissemination[36]. Genes that are important for these activities areALS3,SAP4-6,HWP1,HYR1, andECE1, and their expression can be variable[37], whileSAP1andSAP3andSAP8genes have been correlated with vaginal infections[38].

In the first phase of the infection, which is the adhesion phase, adhesins and invasins allowC. albicanscells to adhere to the substrate, forming a basal layer of cells[39]. Adhesins are glycoproteins that enable yeast to adhere to epithelial and endothelial cells[40]. Invasins are specialized proteins by whichC.albicansstimulates host cells towards endocytosis by binding to host cell ligands[41]. The target ligands are E-cadherin on epithelial cells and N-cadherin on endothelial cells[42]. Numerous genes are involved in adhesion to epithelial cells, and the large cell surface area of the glycoprotein encodes eight genes belonging to theC. albicansagglutinin-like sequence family[43].

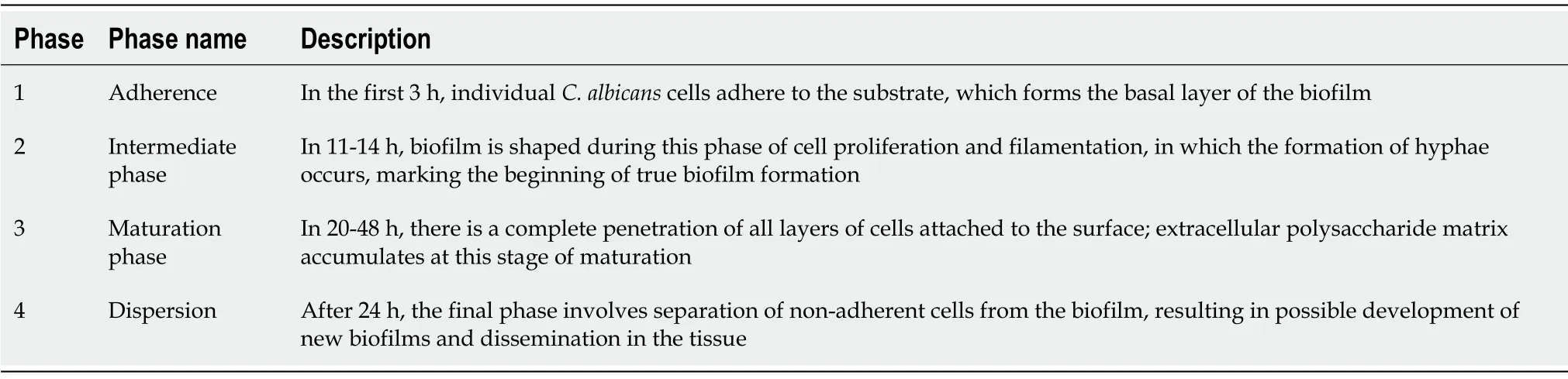

Biofilm production is recognized as a crucial virulence factor (Table 2)[44]. In the proliferation stage ofC. albicanscells, filaments are formed, in which yeast cells begin to develop filamentous hyphae. That is the most critical step in which cells can change their morphology, facilitating in turn biofilm formation on the mucosal surfaces of the host[45,46]. The biofilm formation process is controlled by six genes (EFG1, BCR1, BRG1, NDT80, TEC1,andROB1) that belong to the transcriptional regulatory network[47,48].

Table 2 Biofilm production process

Alongside the aforementioned virulence factors, it is also becoming clear thatC. albicansisolated from patients with diabetes mellitus has more pronounced pathogenic properties[49]. Namely, the hyperglycemic environment, rich in carbohydrates, serves as a source of energy indispensable for producing biofilms and matrices that protect fungal cells from external influences[6]. Most pathological conditions caused byC. albicansare associated with biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces or host surfaces[50]. Yeast cells dispersed from mature biofilm are more virulent and have a more remarkable ability to adhere to surfaces to form new biofilms than planktonic ones[51]. Biofilm production also complicates treatment and contributes to high morbidity and mortality rates[52].

C. albicanscan produce the cytolytic enzyme known as candidalizine, and hyphae are responsible for its secretion[44]. This enzyme plays a vital role in developing vaginal mucosal infections[53]. More specifically, candidalizine has immunomodulatory properties critical in host cell damage[54] and plays a role in neutrophil recruitment during disseminated systemic fungal infections[55].

A direct contribution to the virulence ofC. albicansis the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase as well as hemolysin, which all enhance pathogenic effects such as binding to host tissue and rupture of the cell membrane. As a result of their activity, the invasion of the mucosal surface is facilitated, and they are also responsible for avoiding the host’s immune response[46,56,57]. InC. albicans, at least ten members of the aspartyl proteinase gene family are present, while phospholipase has been reported in four families[58].

Finally, one of the essential contributors toC. albicansvirulence is thigmotropism (contact sensing), which is regulated by extracellular calcium intake and aids significantly in spreading into host tissues and biofilm development[44].

TYPES OF UROGENlTAL CANDlDlASlS lN PATlENTS WlTH DlABETES

Vulvovaginal candidiasis in females with diabetes

Several important pathophysiological mechanisms are involved in the occurrence of vulvovaginitis and vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in individuals with uncontrolled hyperglycemia, leading to increased glucose levels in vaginal mucosa[6]. First of all, yeasts can utilize the glucose found in secretions as a viable nutrient, and additional influence of the overall change in pH and temperature can result in increasedCandidaspp. virulence[59]. Furthermore, the binding ofCandidaspp. to epithelial cells on the vaginal surface represents a pivotal initial step in colonization and ensuing infection with yeasts[60], with an indispensable role of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression for facilitating adhesion after the episodes of hyperglycemia[61]. Recurrent episodes of VVC are more frequent in diabetic patients due to immune suppression, altered leukocyte function, and a myriad of other factors[21].

Several different author groups appraised the association between VVC and diabetes mellitus. For example, Guntheret al[30] studied females with diabetes from Brazil and found thatCandidaspecies were more frequently isolated in them than in those without it (18.8%vs11.8%); likewise, the development of VVC (both isolated and recurrent forms) has been more frequently observed in the diabetic group of patients, together with lower cure rates. In a study on postmenopausal females with diabetes and symptoms of VVC,Candidaspp. were isolated in 15.6% of involved patients using culturing techniques and molecular confirmation withC. albicansleading the way in frequency (59.30%), followed by C. glabrata(24.41%) andC. krusei(16.27%)[62]. These studies also showed different antifungal susceptibilities of isolated species, which is why mycological culture is often endorsed, even though microscopy is often sufficient for visualizing recognizable fungal elements such as pseudohyphae ofC. albicans(Figure 1).

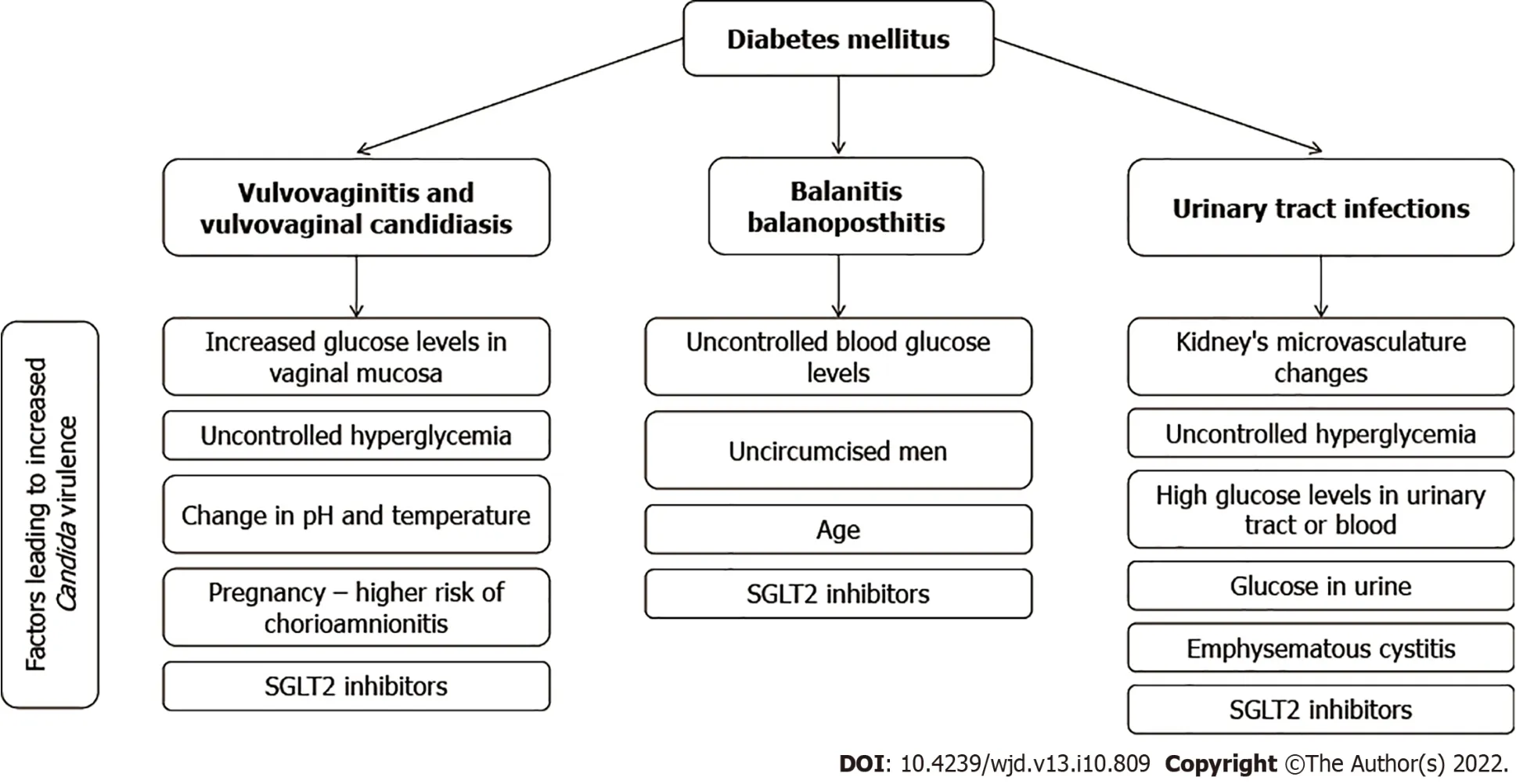

Figure 2 A summary of factors leading to urogenital candidiasis in patients with diabetes mellitus. SGLT2: Sodium glucose cotransporter 2.

However, non-albicans Candidaspecies are increasingly implicated in VVC in cases of patients with diabetes. In a research endeavor by Rayet al[63], which explored cure rates of different treatment modalities,C. glabratahas been cultured in 61.3% andC. albicansin 28.8% of 111 female individuals with VVC and diabetes. A study by Goswamiet al[64], conducted on diabetic females from India, showed a relatively high prevalence (46%) of VVC with a relative risk of 2.45 and a predominance ofC. glabrataandC. tropicalis. Such dominance ofC. glabratain the same context was confirmed by another study from India[65], showing that all therapeutic considerations have to consider country- and regionspecific pathogen distribution (Table 3).

Table 3 Studies of the prevalence of candidiasis in individuals with diabetics

The problem is further aggravated with the use of relatively novel hypoglycemic agents that are known to induce glycosuria, and this specifically pertains to SGLT2 inhibitors. More specifically, the colonization rate withCandidaspp. (and subsequently the risk of VVC) can increase substantially with the use of these agents, reaching up to 37%[4,5]. Another important issue is selecting the optimal treatment approach in females with recurrent VVC and diabetes, especially since many author groups recommend routine prophylactic administration of antimicrobial drugs in preventing candidiasis when faced with uncontrolled diabetes[6,21]. The best approach is still a matter of debate, as even a recent and comprehensive Cochrane review on different pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment modalities highlighted that more research is necessary to ascertain the optimal medication choices as well as dose and frequency for females with diabetes[66].

Balanitis/balanoposthitis due to Candida spp. in males with diabetes

The influence of diabetes on the development of balanitis/balanoposthitis caused byCandidaspp. is well known due to the well-established association of uncontrolled blood glucose levels and the proliferation ofCandidabeneath the prepuce[67]. WhileCandidais a causative agent of less than 20% of all balanoposthitis cases, it is the most commonly observed pathogen in males with diabetes, habitually presenting as a pruritic rash with sores, erosions, or papules (with possible sub-preputial discharge)[68]. In addition, coinfection with other pathogens can worsen the clinical presentation in males with diabetes (not only with common sexually transmitted infections but also pathogens such asStreptococcus pyogenes[69]).

The aforementioned connection between diabetes and penile infection is reflected in population studies as well; for example, the appraisal of all male patients with balanoposthitis from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database in Taiwan revealed that the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus was higher in the balanoposthitis cohort than those without it, with a hazard ratio of 2.55 after age and comorbidity adjustments[70]. Furthermore, a large study from Portugal demonstrated that diabetes mellitus was significantly more prevalent in patients with clinically frank balanitis when compared to the asymptomatic group, and there was also higher colonization withCandidaspecies[71]. In addition, an extensive survey of dermatology specialists from across India, with more than 60000 outpatients in their care, showed that up to 75% of individuals withCandidabalanoposthitis were known cases of diabetes mellitus[72].

Even novel hypoglycemic agents that can induce glycosuria, most notably already mentioned SGLT2 inhibitors, can also increase the risk of genital candidiasis in males (Figure 2). For example, a recent report by Bartoloet al[73] showed the development of balanitis due toC. albicansand subsequent candidemia but also the potential role of other species such asC. glabrata. A severe form of balanoposthitis caused byC. albicansafter treatment with SGLT2 was also described in a 57-year-old with type 2 diabetes coupled with oral candidiasis[74]. Of note, balanitis is rarely seen in circumcised males, as the moist space beneath the foreskin represents an ideal environment for facilitated yeast proliferation[4].

The compounding effect of diabetes and genital candidiasis in pregnancy

The observed incidence of VVC during pregnancy is approximately 15%[75], but this percentage is even higher in pregnant females with either type 1/type 2 diabetes mellitus or gestational diabetes[76]. This means both pregnancy as a physiological process and diabetes as a pathological condition may have a compounding effect in the development of VVC (Figure 2). In a study on 251 pregnant females from Poland, Nowakowskaet al[77] demonstrated a four times increased risk of developing vaginal mycosis in those with type 1 diabetes mellitus as well as a two times increased risk in those with gestational diabetes in comparison with healthy controls. A study on pregnant females from a Malaysian tertiarycare hospital showed that the first and second trimester of pregnancy and diabetes mellitus are significant risk factors for developing VVC[78]. A prospective study from China showed a significantly higher frequency of VVC in females with gestational diabetes (22.6%vs9.7%)[76].

This is important due to the possible development of candida chorioamnionitis in diabetic pregnant females stemming from VVC, with potentially detrimental consequences for the unborn child. Although this clinical entity is relatively uncommon, it was repeatedly described in the medical literature. One of the gravest examples is a case reported by Obermairet al[79] onCandidachorioamnionitis that successively led to a late stillbirth in a pregnant woman with gestational diabetes mellitus. Unfortunately, there were no prior obstetrics procedures in this case, and infection withC. albicanstriggered an inflammatory cascade that resulted in the occlusion of umbilical cord blood vessels, ultimately resulting in fetal death[79].

Recently, Shazniza Shaayaet al[80] reported 2 cases ofCandidachorioamnionitis linked to gestational diabetes and originating from VVC where manifold red and yellowish spots were observed during pathohistological observation on the superficial area of the umbilical cord. Microscopically, these spots were microabscesses laden with yeasts and pseudohyphae, while peripheral funisitis was highlighted as a prominent feature of suchCandidachorioamnionitis. Other reported cases ofCandidachorioamnionitis associated with diabetes mellitus also led to adverse perinatal outcomes such as preterm birth, neonatal sepsis due toC. tropicalis, and the death of one twin as an unfortunate outcome of twin pregnancy[81-83]. The imputable role of diabetes mellitus in the development ofCandidachorioamnionitis after VVC (with potentially serious sequelae for the fetus) cannot be overstated.

Candidiasis in the urinary tract of diabetic patients

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are much more common in individuals with diabetes, and this is also valid for potential complications such as emphysematous cystitis, pyelonephritis, and kidney abscesses[84,85]. Furthermore, type 2 diabetes mellitus is a well-recognized risk factor for both community- and healthcare-associated acquired UTIs, but UTIs are linked to catheterization and following renal transplantation. In all of these scenarios, differentCandidaspecies have a prominent role[6,86]. In addition, in patients with diabetes, the duration of disease and poor glycoregulation in the long run lead to changes in the kidney’s microvasculature and frequent polyuria/glycosuria, which can predispose them to more frequent urinary tract infections[87].

Delineating candiduria from frank UTI is still a controversial topic, as there are no steadfast laboratory criteria. Furthermore,Candidais a recognized commensal of the urogenital tract. Therefore, its presence in the urine sample adds ambiguity to making a definitive diagnosis ofCandidaUTI[88]. A further issue is that candiduria by itself may be the sole indicator of invasive candidiasis, with potentially serious outcomes (particularly in immunocompromised patients)[88]. In any case, the prevalence of candiduria in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus ranges between 2.27% and 30.00% in studies conducted worldwide, with notably higher rates in females[89] (Table 3).

A study from Ethiopia found significant candiduria in 7.5% of asymptomatic and 17.1% of symptomatic patients presenting with diabetes, withC. albicans,C. glabrata,andC. tropicalisbeing the most commonly implicated species[90]. In one study by Falahatiet al[91] from Iran, uncontrolled diabetes, increased fasting blood sugar levels, and glucose in urine were all significantly related with candiduria, with the most frequent species beingC. glabrataandC. albicansin 50.0% and 31.6% of cases, respectively, followed byC. krusei,C. tropicalis, andC. kefyr. This was corroborated by another study from Iran, where the candiduria rate was also high in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus that presented with inadequate blood glucose control[89]. The most frequently isolated species in the latter study wasC. albicans(47.5%), followed byC. glabrata(37.5%),C. kefyr(10.0%), andC. krusei(5.0%)[89]. A recent study from Iran on 1450 urine samples highlighted diabetes as the most frequent risk factor for the development of candiduria and the three most common species asC. albicans,C. glabrata,andC.tropicalis[92].

Emphysematous cystitis is a rare complication that is almost exclusively seen in diabetic patients, while fungal microorganisms are seldom implicated in its pathogenesis[6]. Still, uncontrolled diabetes is viewed as a major risk factor for an increasing role ofCandida species (especially non-albicansspecies) in this specific pathology. Wanget al[93] described the case of a 53-year-old man with diabetes from China who presented with two rare and concomitant complications ofC. tropicalisinfection in the urinary tract: a discrete mass known as a fungus ball and emphysematous cystitis. Another study from the United States presented a case of a 49-year-old male with diabetes and emphysematous pyelitis caused byC.tropicalis, where early diagnosis and treatment led to a favorable outcome[94].

Treatment of candidiasis in patients with diabetes

Antifungal therapy is often not justified, even in UTIs caused by different types ofCandida[95]. The assumption is that people with predisposing factors (e.g., diabetes) should first be treated, which may in turn resolve the infection[96]. For individuals who have symptomatic UTIs caused byCandidaspp. and when it is assumed that predisposing factors have been eliminated or at least kept to a minimum, the use of fluconazole is recommended due to the possibility of achieving high concentrations in urine. It can be administered orally, 200-400 mg daily, in a single dose for 14 d. Exceptions are infections caused byC. kruseiandC. glabrata, where amphotericin B deoxycholate is often used (due to inadequate urine concentrations of other azole antifungals and echinocandins)[95]. In instances of resistantCandidaspp. or in high-risk patients, amphotericin B is given intravenously at a dose of 0.3 to 0.6 mg/kg per day in the case of cystitis and given intravenously in a dose of 0.5 -0.7 mg/kg in the case of pyelonephritis[97]. In the case of resistant pyelonephritis, 25 mg/kg of flucytosine is added orally four times a day. The standard treatment regimen is 2 wk. The patient’s kidney function should be taken into account[98]. The use of flucytosine, although very effective in the eradication ofCandidaspp., requires extra caution due to the toxicity it possesses[98]. If used alone, resistance to it occurs very quickly, and therefore therapy is not carried out longer than 7-10 d. Also, the drug is administered every 6 h at a dose of 25 mg/kg[99]. It is important to note that the recurrences of infections caused byCandidaspp. are very common[100].

CONCLUSlON

In conclusion, there is an increasing body of evidence that shows how patients with diabetes (particularly those characterized by unsatisfactorily controlled glycemia) are vulnerable to urogenital mycotic infections withC. albicansand other non-albicans Candidaspecies of increasing importance. We have highlighted virulence factors ofC. albicansand shown how the interplay of many pathophysiological factors can give rise to VVC with increased risk of recurrent episodes and dire pregnancy outcomes. There is also an increased risk of candiduria and UTI development caused by species ofCandidain females and males alike (with the possibility of further complications such as emphysematous cystitis) as well as balanitis and balanoposthitis in (primarily uncircumcised) males. With a steadily increasing global burden of diabetes, these clinical conditions will undoubtedly become more prevalent in the future. All of this underscores the importance of establishing and preserving euglycemia, alongside any introduced antifungal treatment approaches, if our end-goal is to successfully manage urogenital candidiasis in affected individuals with diabetes. Moreover, in order to minimize this high burden of yeast infections in individuals with diabetes, it is pivotal to identify those at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and forestall the rise of complications; consequently, many lifestyle interventions (such as dietary changes, exercise, and weight reduction) have a much better impact than pharmacologic treatment. If the condition arises and the patient is faced with urogenitalCandidainfections, an early and appropriate treatment regimen should be introduced, especially to avoid several complicated conditions, which we have described.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Talapko J substantially contributed to the conception and design of the article, interpretation of relevant literature, article drafting, and table preparation; Meštrović T substantially contributed to the conception and design of the article, interpretation of relevant literature, article drafting, and figure preparation; Škrlec I coordinated the literature search and article preparation and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors report no relevant conflict of interest for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Croatia

ORClD number:Jasminka Talapko 0000-0001-5957-0807; Tomislav Meštrović 0000-0002-8751-8149; Ivana Škrlec 0000-0003-1842-930X.

S-Editor:Wu YXJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wu YXJ

World Journal of Diabetes2022年10期

World Journal of Diabetes2022年10期

- World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Considerations for management of patients with diabetes mellitus and acute COVlD-19

- Everything real about unreal artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy and in ocular pathologies

- New therapeutic approaches for type 1 diabetes: Disease-modifying therapies

- Advances in traditional Chinese medicine as adjuvant therapy for diabetic foot

- Correlation between gut microbiota and glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus

- Effectiveness and safety of human umbilical cord-mesenchymal stem cells for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus