Review with meta-analysis relating North American, European and Japanese snus or smokeless tobacco use to major smoking-related diseases

Peter Nicholas Lee, Katharine Jane Coombs, Janette Susan Hamling

Abstract

Key Words: Smokeless tobacco; Мoist snuff; Lung disease; Сardiovascular disease; Мeta-analysis; Review

lNTRODUCTlON

It is well established[1,2] that cigarette smoking markedly increases the risk of a range of diseases, particularly lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and stroke. Meta-analyses[3] have shown that in North American and European populations, current cigarette smokers, compared with those who have never smoked cigarettes, have about a ten-fold increase in risk of lung cancer, with the extent of the increase rising with amount smoked and earlier age of starting. Relative risks (RRs) exceed three for COPD and, in younger individuals, two for cardiovascular disease[4]. Pipe and cigar smoking is also associated with a clear increase in risk of smoking-related disease[2].

Here, we study the association between current use of smokeless tobacco (ST) and four major smoking-related diseases (lung cancer, COPD, IHD/AMI, and stroke). Our analyses are based on studies published from 1990, and separate out the effects of ST as used in North America, and the effects of moist snuff (“snus”) as mainly used in Sweden and neighbouring countries. Coupled with a separate ongoing attempt to provide updated meta-analyses relating the same diseases to current cigarette, cigar and pipe smoking, our results should help to provide a good picture of the relative effects of the different nicotine products on the major smoking-related diseases.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Attention was restricted to publications in English in the years 1990 to 2020 which provide results relating use of current ST or snus) in non-smokers to the risk of lung cancer, COPD, IHD/AMI or stroke, based on epidemiological cohort or case-control studies conducted in North America, Europe or Japan, and involving at least 100 cases of the disease of interest. The studies selected should not be restricted to those with specific other diseases.

Literature searches

The search procedures are described in detail in Supplementary material and are summarized below. First, separate literature searches on Medline were conducted for lung cancer, COPD or cardiovascular disease, the aim being to identify from these searches not only publications that described studies satisfying the inclusion criteria, but also meta-analyses and reviews that may themselves cite other relevant publications. Then, for each of the three searches, a print-out of the Medline output for title and abstract was examined by Katharine J Coombs (Coombs KJ) to identify publications of possible relevance, the selection then being checked by Peter N Lee (Lee PN), with any disagreements resolved in discussion. The selected publications (and where relevant supplementary files and also other publications linked to them in the Medline search) were then obtained, and examined by Lee PN, and classified as either an accepted publication possibly including relevant data, a reject (giving reason), a relevant review or a relevant meta-analysis. The suggested rejects were then checked by Coombs KJ, with any disagreements resolved. Then additional accepted publications not detected by the Medline searches were sought from examination of reference lists of the accepted papers and of the relevant reviews and meta-analyses.

The accepted publications from the three searches combined were then examined to eliminate those giving results superseded by a later publication, those not providing new data, and those not providing results relating current ST or snus use specifically for the four diseases of interest.

Meta-analyses

Using standard methods[5] individual study RR estimates were combined using fixed-effect and random-effects meta-analysis, with the significance of between-study heterogeneity also estimated.

For studies on ST use in North America, preference was given to results for those who had never used cigarettes, pipes or cigars which compared current and never ST use, but results from studies which only compared ever and never ST use were also considered in some meta-analyses.

For studies on snus use, use of pipes and cigars was disregarded as this was often not reported, and such use is rare in Scandinavia. RRs comparing current snus users both with never users and with nonusers (i.e.non-current users, including both former and never users) were separately considered, as a number of studies only presented results compared to non-use. In some cases these estimates were derived from data separately by current, former and never use. Only age-adjusted RR estimates were considered, with the estimates adjusted for the most other factors generally being used.

RESULTS

Literature searches

The results of the searches are given in detail in Additional File 1 and are summarized below and in Figure 1.

For lung cancer, 131 papers were identified in the Medline searches, with 32 considered possibly relevant from examination of title and abstract, and a further 12 identified from comments on these papers. Examination of the full text from the 44 papers led to 10 being accepted as providing apparently relevant study data, with 23 being reviews or meta-analyses and 11 rejected for various reasons.

For COPD, the Medline searches identified 46 papers with six initially considered possibly relevant based on title and abstract, and no further papers identified from comments. The full text examination led to one of the six papers being accepted and three rejected, with the other two being reviews.

For cardiovascular diseases, the Medline searches identified 308 papers, with 80 initially considered possibly relevant, a number extended to 97 after identification of comments on these papers. Of these 27 were accepted, with 52 being reviews or meta-analyses and 18 rejected.

Examination of reference lists in accepted papers, reviews and meta-analyses led to ten further papers being considered possibly relevant, but only one of these was a paper describing relevant results (for COPD). The total of 39 accepted papers for the diseases combined, was then reduced to 26, as three had been accepted in two separate searches, four did not give results for non-smokers, one did not separate results for IHD and stroke, and five were only comments on other accepted papers and provided no new data. Of the 26 papers, 18 gave results for snus, and eight for ST as used in the United States (US), considered separately below. No relevant results were found for Japan.

Figure 1 Literature searches. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

ST use in the US

Each of the eight publications identified[6-13] reports results from a prospective study. Results from one[10] were not considered further as a later publication[11] provides corrected results from the same study.

The most relevant results, comparing risks for currentvsnever ST users in those who had never used cigarettes, pipes or cigars, come from four studies. For Cancer Prevention Studies I and II (CPS-I and CPS-II), separate results for each of the four diseases are available in one publication[9]. For the National Longitudinal Mortality Study (NLMS), results for IHD and stroke from one publication[13] are preferred to those from another[8], due to the longer follow-up considered, though results for lung cancer are only available from the latter publication[8]. For the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), the results from one publication[11] are preferred, as they provide results for all four diseases, and for a longer follow-up than do other publications[8,12].

Less useful are results from two studies. For the Agricultural Health Study (AHS), the results[7] are only for lung cancer, and only compare ever and never ST use. For the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the results[6], for all the diseases except COPD, only compare ever and never ST use, with pipe and cigar smokers not excluded.

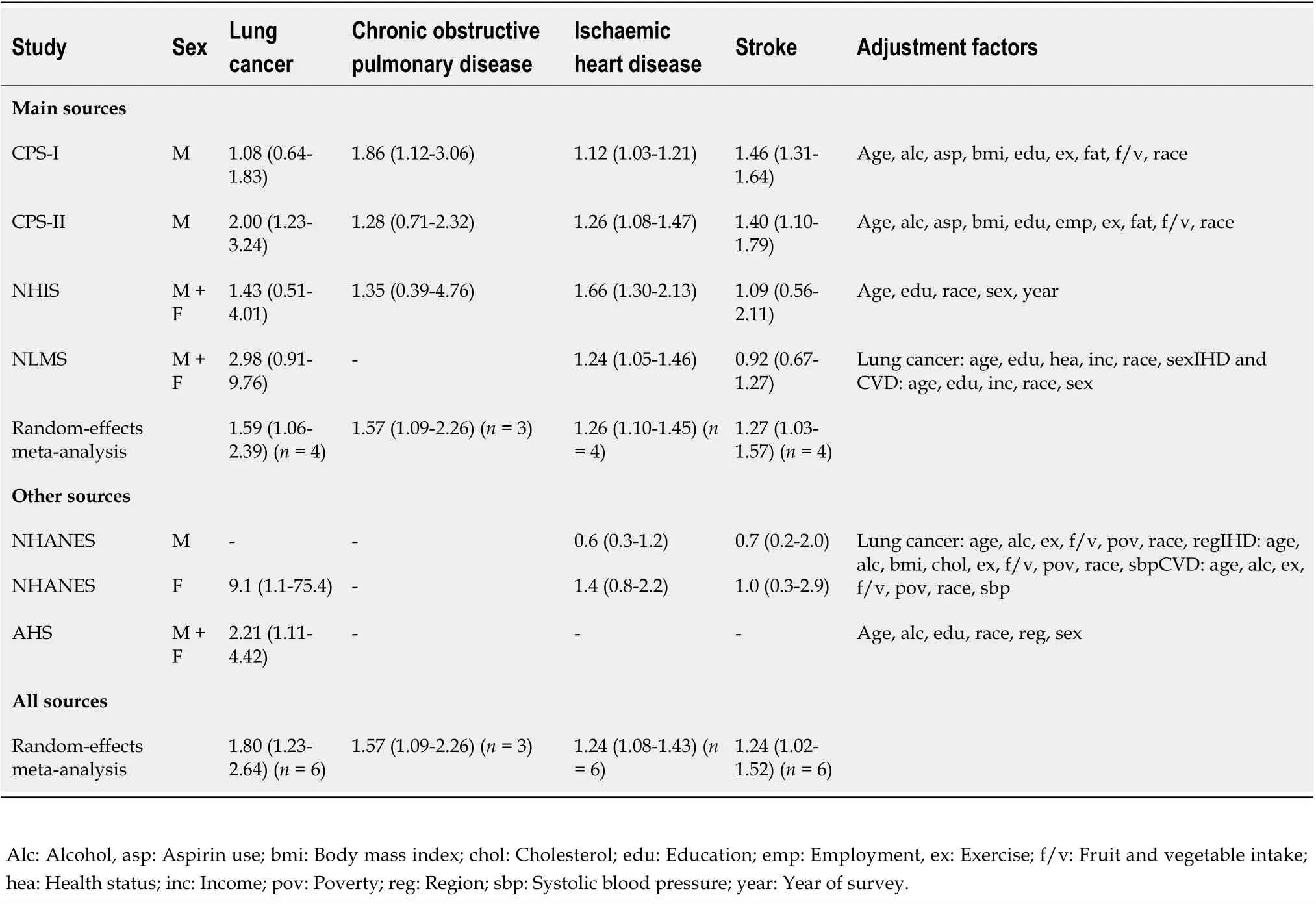

Table 1 gives a summary description of the six studies considered, including timing, population studied, and relevant diseases considered, as well as the ST exposure index used and whether pipe and cigar smokers are excluded from the results for never smokers.

Table 2 gives the RRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), both as reported for the individual studies and as estimated for the combined studies using random-effect meta-analysis, as well as the available results by sex, and the adjustment factors taken into account. Two studies report results only for males, three for sexes combined and only one for the sexes separately. All the RRs were adjusted for age and a varying list of other factors, including sex where relevant.

The combined evidence from the main studies (CPS-I, CPS-II, NHIS, NLMS) shows a statistically significant increase in risk relating to current ST use which is somewhat greater for lung cancer (RR 1.59, 95%CI: 1.06-2.39) and COPD (1.57, 1.09-2.26) than for IHD (1.26, 1.10-1.45) and stroke (1.27, 1.03-1.57). Including also the evidence from the other two studies (AHS, NHANES) somewhat increased the combined RR estimate for lung cancer (to 1.80, 1.23-2.64) but left the RRs for the other three diseases virtually unchanged. Significant evidence of heterogeneity between the estimates was only seen in the analyses for IHD, where due to a rather higher estimate from NHIS, the associatedPvalue was 0.019 for the estimate based only on the four main results, and 0.015 when also including the results from NHANES.

There is also information from three of the studies on variation in risk by type of ST (chewing tobacco or snuff). For CPS-II[9] RRs were reported, for lung cancer, IHD and stroke, respectively of 1.97 (95%CI: 1.10-3.54), 1.25 (1.03-1.51) and 1.38 (1.02-1.86) for exclusive chewing tobacco use, and of 2.08 (0.51-8.45), 1.59 (1.06-2.39) and 0.62 (0.23-1.67) for exclusive snuff use. For AHS[7] the RR of lung cancer for chewing tobacco of 2.20 (0.98-4.97) was similar to that of 2.21 (1.11-4.42) for overall ST use. No result was given for snuff, as there were only three cases of lung cancer in the exposed group. For NLMS[13] RRs for IHD were 1.11 (0.88-1.42) for exclusive chewing tobacco and 1.30 (1.03-1.63) for exclusive snuff use. In all three studies, the RRs did not vary significantly by type of ST.

Snus use in Scandinavia

Of the 18 publications on snus[14-31], one[16] describes results from a study in Norway, with the rest describing studies in Sweden. Most describe results from a single study, but one[14] presents separate results from two studies, while two[20,21] present results from eight studies, one for AMI and the other for stroke. All the available results are for males.

Two papers were not considered further. One[30] only reported results for evervsnever snus use, reported RRs in never smokers only for combined cardiovascular death (RR 1.15, 95%CI: 0.97-1.37) and respiratory death (0.8, 0.2-3.0), and did not separate out results for IHD/AMI, stroke or COPD. The other[14] mainly considered heart failure, the limited results for AMI being unrestricted to non-smokers and not adjusted for any potential confounding factors.

Table 2 Relative risks in analyses of smokeless tobacco risk among never smokers in the United States

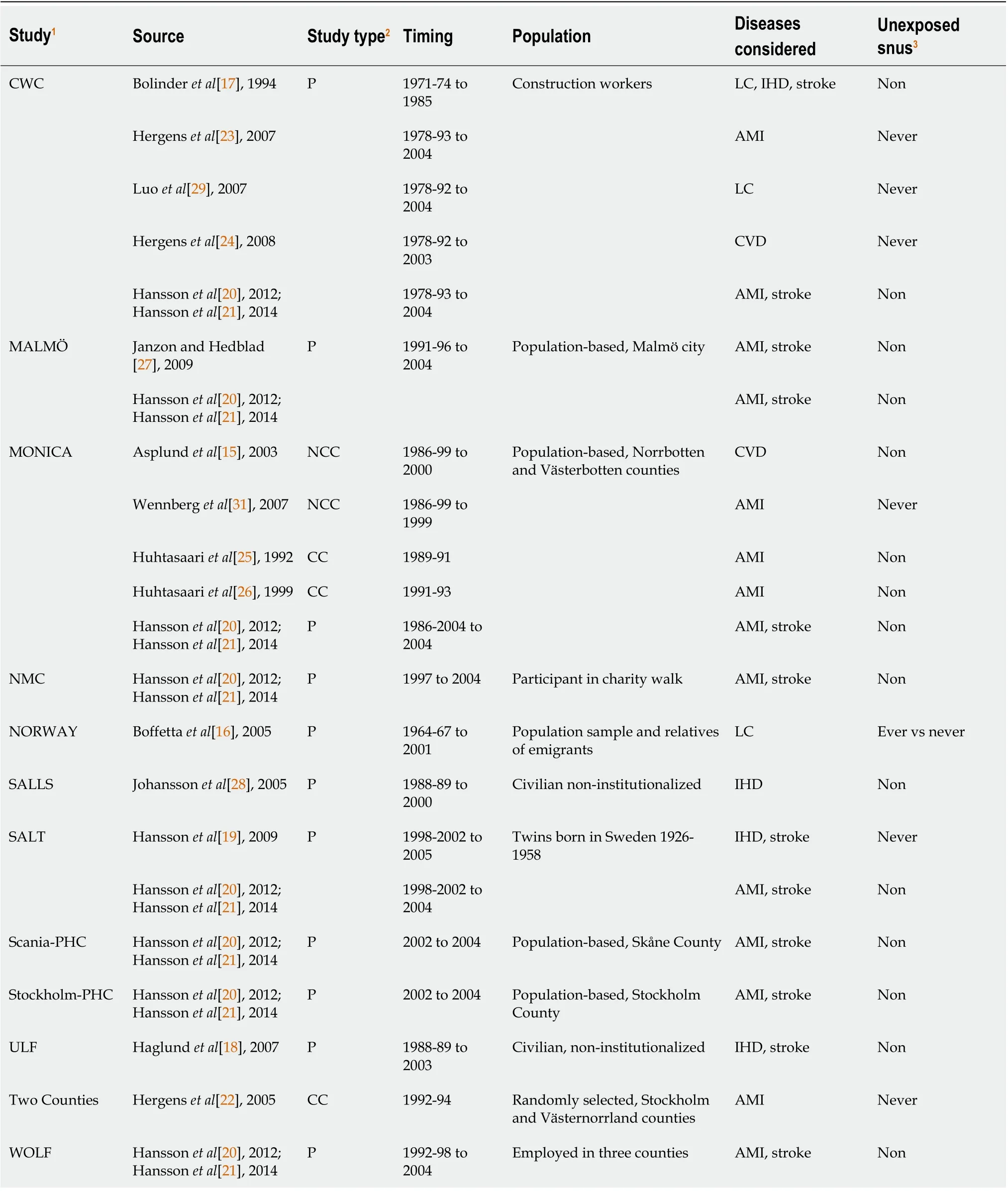

The other 16 studies all present results for snus use in non-smokers or non-regular smokers, in some where the comparison is between current and non-use rather than between current and never use, and one where it is between ever and never use. Table 3 gives details, by study and publication, of the study type, timing, population, relevant diseases considered, and the unexposed group considered. In total there are results from 12 studies, with multiple publications describing results from some studies. For no study did any of the publications present simple updates of results given in another publication. All but the Two Counties study is of prospective design, though some results from the MONICA study are based on case-control analyses.

From Table 3 it can be seen that there are no results at all for COPD (or a closely related endpoint) and only three publications present results for lung cancer. The most useful result[29] is based on follow-up of construction workers interviewed in 1978-92, including 15 cases in current users and three in former users, with a RR of 0.80 (95%CI: 0.40-1.30) for current vs. never ST use and of 0.80 (0.45-1.45) for currentvsnon ST use. An earlier result from this study[17] can be ignored, as it is based on no more than three lung cancer cases in current users, and based on interviews in 1971-74, when coding of smoking status was problematic[29]. A RR of 0.96 (0.26-3.56) from the Norway study[16] is for evervsnever use and based on only three cases in ever users. No meta-analyses seemed to be worth conducting for lung cancer.

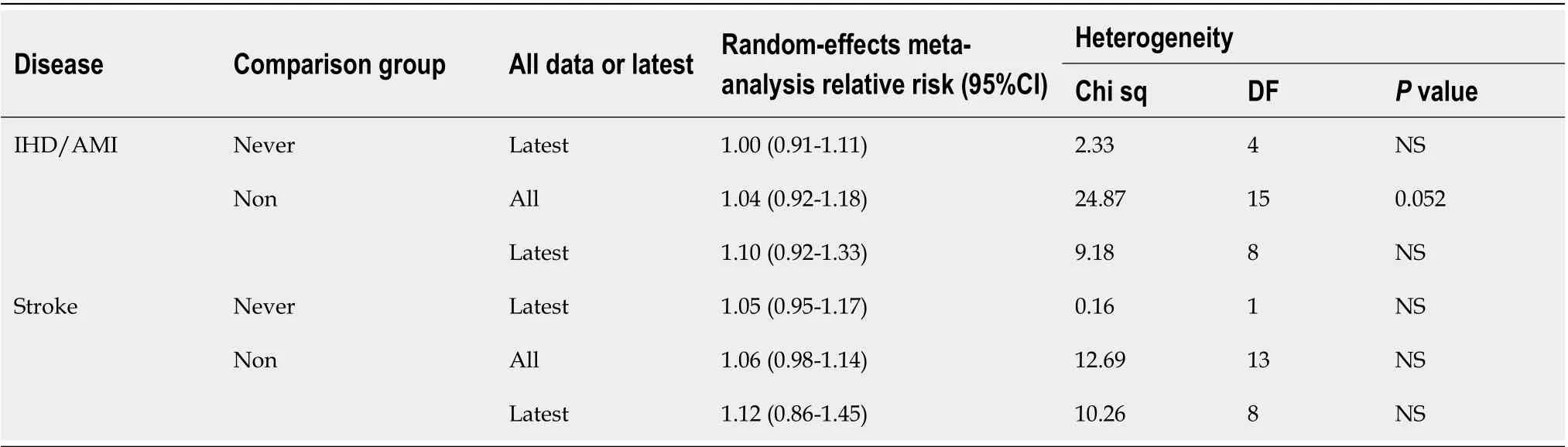

As illustrated in Table 4, much more evidence is available for IHD/AMI and stroke, both for current vs. non snus use and for currentvsnever use, each RR estimate being adjusted for age and varying other factors. Based on the estimate from the latest publication, where data for a study provides a choice, Table 5 shows no evidence of an increased risk in current snus users, whether the comparison group is never users (IHD/AMI: RR 1.00, 95%CI: 0.91-1.11; stroke: 1.05, 0.95-1.17), or is non users (IHD/AMI: 1.10, 0.92-1.33; stroke 1.12, 0.86-1.45). No significant association is also seen when, less satisfactorily, all available RRs are combined, regardless of whether in some studies some disease occurrences may be counted more than once.

DlSCUSSlON

The results of the meta-analyses for ST use in the US show that, in those who have never used cigarettes, cigars or pipes, current use, compared to never use, is associated with a significant increase in risk of all four major smoking-related diseases studied, the increases estimated from the four main sources of data (CPS-I, CPS-II, NHIS, NLMS) being almost 30% for IHD and stroke and almost 60% for COPD and lung cancer. These increases are less than those associated with cigarette smoking,e.g.[4]) and suggest that ST, as used in the US, is a safer, but not harmless, alternative method of nicotine exposure than cigarette smoking for smokers not willing to quit. While some of the publications we consider[6,10] have concluded that an excess risk of smoking-related disease associated with ST use in the US has been shown, some are more cautious, regarding the evidence as limited[9,13].

Table 3 Studies considered in analysis of current snus use among non-smokers in Scandinavia

Table 4 Relative risks in analyses of ischaemic heart disease/acute myocardial infarction and stroke in relation to current snus use among never smokers in Scandinavia

Limitations of the evidence for US ST include the fact that a number of the studies considered are quite old, with three of the seven studies summarized in Table 1 involving follow-up periods ending over 20 years ago, ignoring the possibility that the nature of the products studied may have changed over time. Another limitation is the fairly sparse evidence comparing risk by type of ST product. Although this does not suggest any marked differences in risk between those who use chewing tobacco or use snuff, the data are insufficient to reliably detect smaller differences. Also, it is possible that some misclassification of smoking status has taken place, with some of the effects attributed to ST use actually being a consequence of unreported current or past smoking of cigarettes, pipes or cigars.

Table 5 Meta-analyses of ischaemic heart disease/acute myocardial infarction and stroke results in relation to snus use among never smokers in Scandinavia

Even if the magnitude of the effect on risk of current ST use in the US may be somewhat inaccurately measured in our meta-analyses, there seems little doubt that it is substantially less than that for cigarette smoking. For lung cancer, for example, RRs for current cigarette smoking for the US have been estimated as 11.68 in one meta-analysis[3], with RRs increasing with increasing amount smoked and earlier age of starting to smoke, and higher for squamous cell carcinoma than for adenocarcinoma. While we have not attempted to quantify risk of ST use in the US by amount or duration of use, or by subdivision of the diseases considered, this does not affect the conclusion that the risks of the four diseases for ST are less than for cigarette smoking.

The results of our meta-analyses for current snus use, based on studies in Scandinavia, show no clear evidence of any increased risk, whether the comparison group is never or non-users. While there is little evidence for lung cancer, and there are no useful results for COPD, the evidence for cardiovascular disease is based on as many as 12 studies, the results from some being reported in multiple publications (see Table 4). As shown in Table 5, RR estimates for IHD/AMI and for stroke vary only from 1.00 to 1.12, and none are statistically significant. Though a lack of effect cannot be demonstrated, and it is possible that there is a true small increase in risk by perhaps about 5%, it seems likely that any increase is less than for US ST, and much less than that for cigarette smoking. Certainly the great majority of the publications from which we derived data[14-16,18-22,25-31] considered that no increased risk in current snus users had been demonstrated for any of the smoking-related diseases we considered, many concluding that components of tobacco smoke other than nicotine appear to be involved in the relationship of smoking with heart disease and stroke. However, possible effects were noted for cardiovascular disease[17] based on early and unreliable data[29], fatal AMI and fatal stroke[23,24] and for heart failure[14]. The at most very weak association of snus with the smoking-related diseases considered was also the conclusion of a review of the evidence on snus[32], though this review also noted a possible effect of snus on reduced survival from AMI and on heart failure, arguing that further investigation was needed to investigate possible confounding by socio-economic status or other factors.

But no one appeared, and even after another long sleep, from which he awoke completely refreshed, there was no sign of anybody, though a fresh meal of dainty cakes and fruit was prepared upon the little table at his elbow

In the last few years there have been a number of reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of ST,e.g.[33-42], many unrestricted to effects in the US and Scandinavia, and some restricted to specific diseases. Where effects are claimed, they often relate to products used in Africa or Asia,e.g.[42], or to other diseases, such as oral or pancreatic cancer. For oral cancer, however, evidence of an increased risk from snus has not emerged from meta-analyses[32], while for US ST any increase is mainly evident in studies before 1980[43]. Also, for pancreatic cancer, claims of any increased risk associated with snus use[33,34] are weakly based, with the evidence for any association with ST use essentially disappearing[32] following publication of pooled analyses[44,45]. For lung cancer, the reviews,e.g.[33,34,38,46] generally consider that no increased risk from snus has been demonstrated, though one[39] points to increased risk from US ST. COPD is little considered in the reviews, though one[39] does refer to the increased risk seen in the CPS-I study shown in Table 2. The risks of IHD/AMI and stroke are more extensively considered in the reviews, and some,e.g.[35] refer to a possible increase in risk of fatal AMI and stroke. However, this increase is mainly dependent on the results for US ST, where we have found a significant increase in our analyses. For snus, where the evidence considered derives from studies of fatal cases only, of non-fatal cases only, or of first occurrences of a case (fatal or non-fatal), where separate results are not always reported by fatality, there is no clear evidence of an increased risk specifically in fatal cases[32]. As noted in this review, confounding may occur due to snus users reporting disease later, or having less medical care when they do. Even if, for some reason, there is a slight adverse effect of snus on fatal AMI and stroke, it is clearly less than for cigarette smoking. This conclusion is consistent with a recent follow-up of almost 75000 patients admitted with a first percutaneous intervention, which found that snus use was not associated with increased mortality, new revascularisation or hospitalisation for heart failure[47].

Taken as a whole, the conclusions reached in the reviews are consistent with our findings that, for the four major diseases considered, effects of the smokeless products commonly used in the US are less than those for cigarette smoking, and they are not clearly evident for Swedish snus. Our analyses provide no information on risks from ST as used in Africa and Asia.

CONCLUSlON

Studies in the US show that, in those who never used other tobacco products, current ST use is associated with an increased risk of the four major smoking-related diseases. However, this increase, though statistically significant (atP< 0.05), is much less than for cigarette smoking. Scandinavian studies show no significant increase in risk of IHD/AMI, stroke or lung cancer in current snus users, with no data available for COPD. Though the data have limitations, providing information only on risks from the major smoking-related diseases, and none on risks from the smokeless products used in Africa or Asia, our findings clearly show that risks of the diseases considered from US ST and snus use are much less than for smoking.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

There are extensive data on the risks from cigarette smoking, but far less on the risks from moist snuff (“snus”) or smokeless tobacco (ST) as used in Western populations and Japan.

Research motivation

To obtain recent evidence as part of a project comparing risks from use of various tobacco products.

Research objectives

To summarize data relating snus and ST use in North America, Europe and Japan to risk of the four main smoking related diseases - lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), ischaemic heart disease (IHD) (including acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke.

Research methods

Medline searches sought English publications in 1990-2020 providing data on risks of each of the diseases relating to current (or ever) use of snus or ST in the selected regions. The studies had to include at least 100 cases of the disease considered, and not be based on individuals with specific diseases. Relative risk estimates adjusted at least for age were extracted for each study and combined using random-effects meta-analyses.

Research results

Research conclusions

Risks from ST use in North America are much less than for smoking, while no risks were demonstrated for snus.

Research perspectives

The results suggest that smokers unwilling to give up nicotine may substantially reduce their risk of the four diseases by switching to ST (as used in North America) or snus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Yvonne Cooper for typing the various drafts of the paper and obtaining the relevant references.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Lee PN planned the study; Literature searches were carried out by Coombs KJ and checked by Lee PN; Statistical analyses were carried out by Hamling JS and checked by Lee PN; Lee PN drafted the text, which was checked by Coombs KJ and Hamling JS.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have carried out consultancy work for many tobacco organizations.

PRlSMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the Prisma 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the Checklist's requirements.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United Kingdom

ORClD number:Peter Nicholas Lee 0000-0002-8244-1904; Katharine Jane Сoombs 0000-0003-0093-7163; Janette Susan Hamling 0000-0001-7788-4738.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Liu JH

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2022年3期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2022年3期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Difference in incidence of developing hepatocellular carcinoma between hepatitis B virus-and hepatitis C virus-infected patients

- Clinical outcomes of the omicron variant compared with previous SARS-CoV-2 variants; meta-analysis of current reports

- ls cellular therapy beneficial in management of rotator cuff tears? Meta-analysis of comparative clinical studies

- Evidence analysis on the utilization of platelet-rich plasma as an adjuvant in the repair of rotator cuff tears

- Rare post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography complications: Can we avoid them?

- Viral hepatitis: A narrative review of hepatitis A-E