Fluctuation of visual analog scale pain scores and opioid consumption before and after total hip arthroplasty

lNTRODUCTlON

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most common and successful orthopedic procedures[1]. Arguably one of the greatest improvements in THA peri-operative management over the last decade has been the continuous advancements in pain management regimens that have greatly improved the rate of recovery following the procedure[2-4]. However, due to the highly invasive nature of the procedure, postoperative pain becomes difficult to avoid entirely despite advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative protocols[5]. While joint-related pain is expected to steadily subside after surgical rehabilitation, numerous patients report persistent pain leading to the development of chronic pain postoperatively[6]. Furthermore, the amount of pain that patients experience may perhaps be the most important determinant of satisfaction after THA[7]. Some previous studies suggest that patients who consume more opioids report less satisfaction with pain relief and greater pain intensity[8,9].

Opioids have long been established as a primary analgesic modality for patients undergoing THA and are prescribed routinely for acute pain management following surgery[10]. However, opioid misuse remains a rapidly growing public health crisis which has led to a heightened focus on conservative prescribing patterns in orthopedic surgery[11]. Recent data suggests that the United States ranks number one among all other countries worldwide in daily narcotic consumption[12]. Specifically, orthopedic surgeons are the third-highest group of opioid prescribers among physicians, accounting for almost 8% of all opioid prescriptions in the United States[13]. Limiting access to unused medications while ensuring adequate pain management has been a proposed strategy for improving current prescription practices[14-16]. Although recent studies have highlighted a pattern of patients receiving excess opioid medication after undergoing various orthopedic procedures, there has been minimal evidence to suggest an optimal supply of pain medication postoperatively[16-23]. Therefore, in order to create a safe and effective prescribing guideline that minimizes the over-prescription of opioids and to effectively advise patients pre- and postoperatively, it is imperative to discern the relationship between pain severity and opioid consumption.

The visual analog scale (VAS) is a simple and frequently used method to quantify variations in pain intensity for both clinical and investigational purposes[24-26]. The assessment of pain is generally difficult due to its multifaceted subjective nature, which can vary among individuals. Despite this diversity, the VAS pain questionnaire is widely used in the literature and clinical practice. It is a simple patient-reported outcome tool and requires relatively little patient training to measure pain scores. To our knowledge, no previous study has analyzed the relationship between VAS pain scores and perioperative opioid consumption in patients undergoing THA.

Then there was a terrible crash, as of a world crumbling to pieces,and the angel-child was rising from the earth, and holding her bythe sleeve so tightly that she felt herself lifted from the ground;but, on the other hand, something heavy hung to her feet and draggedher down, and it seemed as if hundreds of women were clinging toher, and crying, If thou art to be saved, we must be saved too

Our institution implemented a novel opioid-sparing protocol for all patients undergoing THA beginning in October 2018 (Supplementary material). The previously established World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder was used as a framework for the development of this novel protocol[28]. With the addition of this protocol, our healthcare providers and patients adhere to standardized order sets for the administration of multimodal analgesia medications throughout the perioperative period[4,29]. Within one month of planned THA, patients are evaluated at our institution’s preadmission test center. Thorough medication reconciliation is performed and patients who are actively consuming opiates are advised and instructed to taper or discontinue its usage prior to undergoing surgery.

But perhaps my favorite version of the tale comes from James Thurber s The Little Girl and the Wolf. Red Riding Hood is not fooled by the wolf, but takes a gun from her basket and shoots him. Thurber explains, It is not so easy to fool little girls nowadays as it used to be. You can find full bibliographic34 references for this short story and the others mentioned in these notes on the Modern Interpretations of Little Red Riding Hood Page.Return to place in story.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Study design

A retrospective review of prospectively collected data was performed at a tertiary, urban, academic medical center to identify consecutive patients who underwent primary, elective THA from November 2018 to May 2019. The inclusion criteria comprised patients who answered both the VAS pain and opioid medication questionnaires pre- and postoperatively. Results from both surveys were separated into four time points for analysis (preoperative, postoperative days 1-7, postoperative days 8-14, and postoperative days 15-30). Patients under the age of 18, those undergoing THA for non-elective or oncologic reasons, revision THA, those who did not have a recorded response for both questionnaires, and any patient receiving opioid pain medications for conditions not related to their operative hip were excluded from this study. A total of 1142 primary THAs were performed at our institution within the period of interest, of which, 270 (24%) were performed by the senior author (Davidovitch RI). All cases included in this study were performed by the senior author (Davidovitch RI) utilizing a direct anterior approach with the assistance of fluoroscopy.

All patients participated in our institutional-wide comprehensive total joint pathway program, which encompasses standardized protocols for all aspects of perioperative care and postoperative rehabilitation. The records and existing data are de-identified and are part of our institutional quality improvement program; therefore, the present study was exempt from human-subjects review by our institutional review board.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes measures included VAS pain scores and opioid consumption over time. VAS pain scores were calculated based on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 representing no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable[24,25]. The VAS pain score was selected as an outcome measure based on its ability to detect immediate changes with a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) ranging from 1.86 to 2.36 for THA[25]. Opioid consumption was defined as the number of narcotic pills taken per day. The various opioids reported by patients included tramadol, hydromorphone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine sulfate[27]. Mean VAS pain scores and opioid pills consumed preoperatively were compared to the means on postoperative days 1-7, days 8-14, and days 15-30 to determine the time point at which postoperative opioid consumption decreases below preoperative consumption and its relation to VAS pain scores. Postoperative time points and the calculation of their means were chosen to provide a comparison to the baseline seven-day interval measured preoperatively.

When the question becomes who s catching9 who, little Georgie knew what to do. It s silly to fish when fishing s no fun, so he dropped his pole and started to run.

The Queen assured him of her eternal gratitude38, and promised, should he succeed, to give him her daughter in marriage, together with all the estates she herself owned

Opioid-sparing pain protocol

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the association between the quantity of opioid consumption in relation to VAS pain scores both pre- and postoperatively in patients undergoing primary THA. We hypothesize that both opioid consumption and VAS pain scores will decrease for all patients following surgery when compared to their preoperative status.

In the operating room, patients are given initial propofol infusions for sedation. Subsequently, patients receive a single dose of spinal anesthetic containing 0.5% ropivacaine or 0.5% bupivacaine. Prior to wound closure, patients are administered two separate homogenously diluted 60-cc injections by the operating surgeon. The first injection was a cocktail containing 20 cc of liposomal bupivacaine (one vial) mixed with 40 cc of 0.9% normal saline solution while the second injection was a cocktail containing 40 cc of non-liposomal bupivacaine (0.25% weight/volume) and 15 mg of ketorolac with 20 cc of 0.9% normal saline solution. All patients receive a total of two grams of intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid (TXA). One gram before surgical incision and another gram during surgical wound closure. Patients who could not receive IV TXA [contraindication for TXA administration: (1) Subarachnoid hemorrhage (2) Intravascular clotting; and (3) Known tranexamic acid hypersensitivity] received 3 g topically in the wound mixed in 100cc saline solution.

Future research should aim to consider other patient factors that influence pain severity. Our current understanding of the independent impact of pain on opioid consumption after THA remains inconclusive.

The purple heather still extends for miles, with its barrows and aerial spectacles, intersected with sandy uneven roads, just as it did then; towards the west, where broad streams run into the bays, are marshes and meadows encircled by lofty, sandy hills, which, like a chain of Alps, raise their pointed summits near the sea; they are only broken by high ridges of clay, from which the sea, year by year, bites out great mouthfuls, so that the overhanging banks fall down as if by the shock of an earthquake

Data collection

Administer surverys to aassociate VAS pain scores with opioiid pill consumption.

This information can be used to set patient expectations and allows surgeons to tailor their prescribing habits based on pain intensity reported by their patients.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). The data were organized using Microsoft Excel software. Baseline demographic characteristics of the study participants were tallied for each variable collected. Descriptive data are represented as means ± SD or counts (%). Hierarchical Poisson regression was used to compare mean opioid pill consumption preoperatively to postoperative days 1-7, days 8-14, and days 15-30. Hierarchical linear regression was used to compare VAS pain scores preoperatively to postoperative days 1-7, days 8-14, and days 15-30. The incidence rate ratio and exponentiated beta coefficients are also reported along with an associated 95% confidence interval (CI). Avalue of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

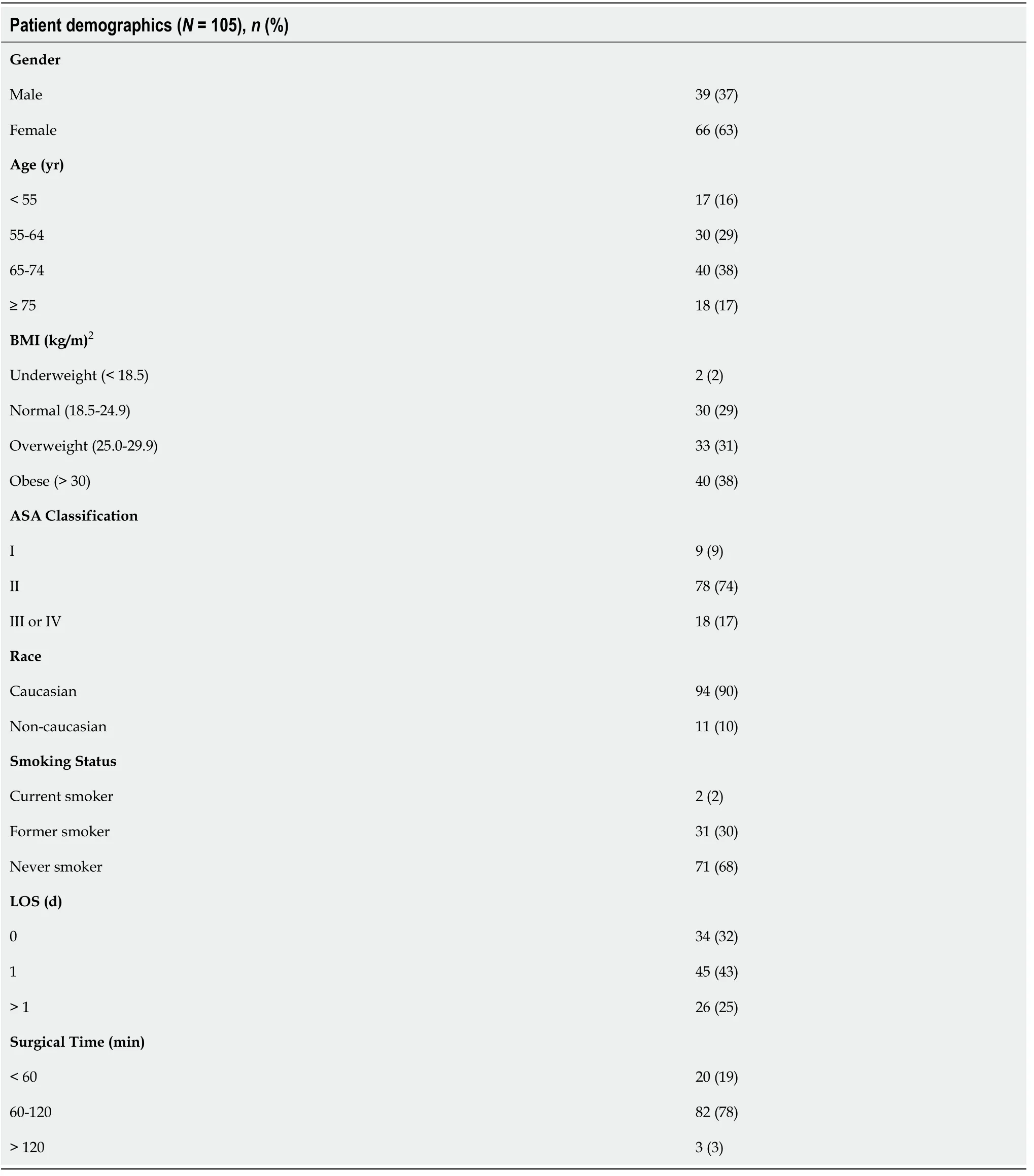

A total of 105 patients were identified who underwent primary THAa direct anterior approach with the assistance of fluoroscopy. The majority of the study participants were female (63%), between the age 65-74 years old (38%), had a BMI < 30 kg/m(62%), ASA class II (74%), Caucasian (90%), and nonsmokers (68%). Additionally, the majority of the patients in this study had a surgical time spanning between 60-120 min (78%) and an in-hospital LOS of 1 day or less following surgery (75%). Full demographic details are highlighted in Table 1.

Opioid consumption and VAS pain scores

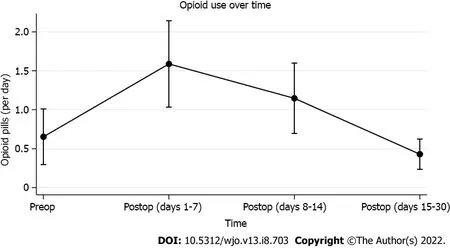

The average number of opioid pills consumed preoperatively was 0.68 ± 1.29. The number of opioids consumed between postoperative days 1-7 (1.51 ± 1.58;= 0.001) and postoperative days 8-14 (1.00 ± 1.27;= 0.043) was significantly greater when compared to patients’ preoperative opioid consumption. However, opioid consumption between postoperative days 15-30 did not significantly differ from their preoperative status (0.35 ± 0.72;= 0.160). This suggests that despite an initial rise in opioid requirements postoperatively, patients experience a decreased need for pain relief 15-30 postoperatively and in fact have a similar if not less opioid consumption in comparison to their preoperative opioid consumption level (Figure 1). These findings are summarized in Table 2.

In a moment all the guards awoke, seized the Prince and beat him mercilessly with their horse-whips, after which they bound him with chains, and flung him into a dungeon

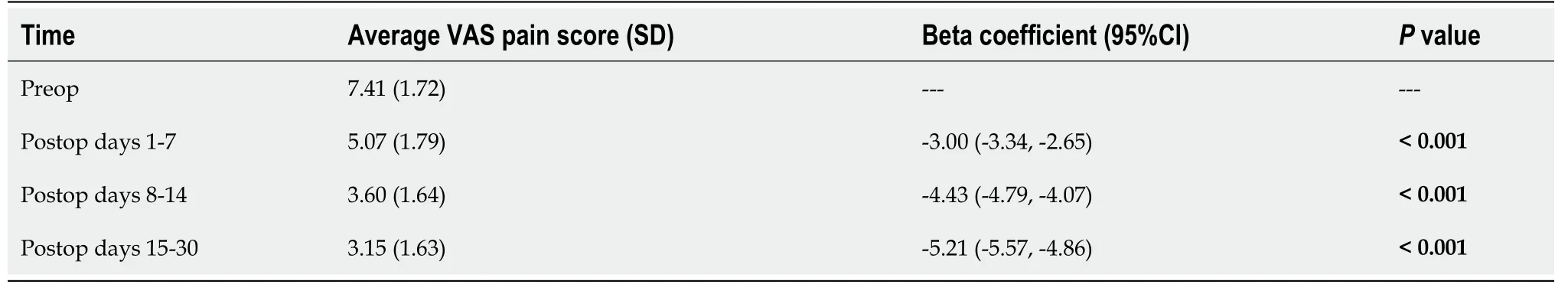

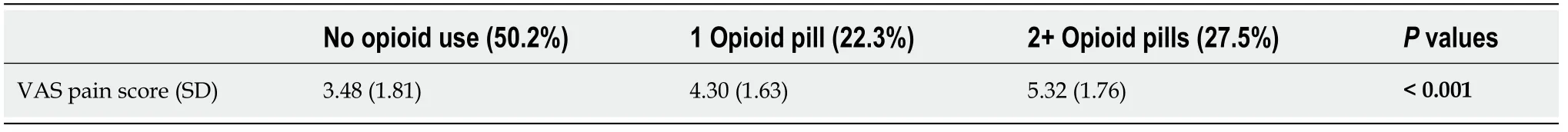

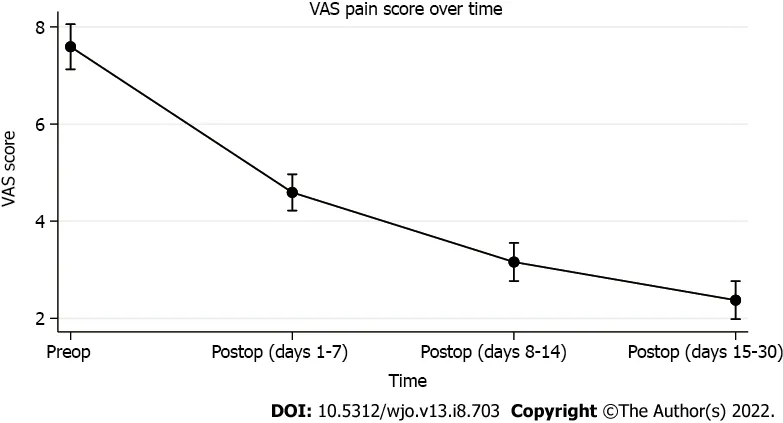

The mean VAS pain score for the study participants preoperatively was 7.41 ± 1.72. This significantly differed from the VAS pain scores between postoperative days 1-7 (5.07 ± 1.79;< 0.001), days 8-14 (3.60 ± 1.64;< 0.001), and days 15-30 (3.15 ± 1.63;< 0.001) (Table 3). The differences exceeded the proposed MCID for the VAS pain score, making these findings clinically significant. Furthermore, the mean VAS pain score between postoperative days 15-30 correlated with a decline in opioid consumption below patients’ preoperative opioid consumption status. The average postoperative VAS pain score of patients who did not take opioids was approximately 3.50, which suggests that a general decline in pain occurs at roughly days 8-14 postoperatively and becomes much lower between postoperative days 15-30 (Figure 2). Additionally, there was a significant linear relationship between VAS pain scores and the number of opioid capsules consumed, which may indicate that as patients’ perception of their pain intensified, their reliance on opioid pain medication increased accordingly (< 0.001; Table 4).

DlSCUSSlON

The impact of opioids has gained significant clinical and research interest given their potential to prognosticate postoperative outcomes and patient satisfaction. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of the relationship between opioid use and pain is essential given the shifting emphasis placed upon health safety and quality.

Bot[9] found that opioid use preoperatively along with lower patient self-efficacy were the best predictors of decreased satisfaction, and the administration of more opioids does not improve satisfaction with pain relief. This is consistent with our findings as patients reported higher VAS pain scores as their opioid intake increased. However, there have been few studies that have documented a correlation between greater opioid use and higher satisfaction with pain relief[39,40]. Carragee[41] compared morphine use following a femur fracture in both the American and Vietnamese populations and found that although American patients used much more morphine in comparison to Vietnamese patients (30 mg/kg0.9 mg/kg), they were less satisfied with their pain relief. Perhaps, drug dependence or addiction may be a confounding factor in achieving satisfaction with pain relief. Vranceanu[42] previously cited effective coping strategies (higher self-efficacy) as the most effective pain reliever. It may be that significant preoperative opioid intake reflects greater psychologic distress that translates to higher reported subjective pain scores postoperatively.

In our study, both opioid consumption and VAS pain scores decreased successively at each of the timeframes evaluated. This implies that patients needed fewer opioid pills as time progressed but were still able to achieve significant pain relief. Implementing standardized, evidence-based opioid prescribing protocols may optimize the number of opioid prescriptions provided to patients and are particularly paramount for patients at risk of transitioning from short-term to long-term opioid therapy postoperatively[4,16,43-45]. Interestingly, the VAS pain score between postoperative days 1-7 was less than patients’ preoperative status; however, the number of opioid pills consumed was higher during postoperative days 1-7. We postulate this may be due to the increased perceived pain burden experienced by patients after undergoing such an invasive procedure.

The amount of opioids prescribed after orthopedic procedures vary widely in the literature, and only a few established guidelines exist that have standardized acceptable duration and magnitude of opioid use[17,46]. Our findings showed that patients ceased to depend on opioids between postoperative days 15-30 compared to their preoperative consumption status, which correlated to a mean VAS pain score of 3.15. This information can be used to set patient expectations and allows surgeons to tailor their prescribing habits based on pain intensity reported by their patients. However, other risk factors in addition to pain also need to be considered. Patients with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety are more likely to be prescribed opioids at both higher doses and for longer durations[47,48]. Not only have previous studies reported that prolonged opioid use may induce depression, but also that depressed patients seek medical attention for pain more frequently, and are three times more likely to be prescribed chronic opioid therapy[49,50]. Rhon[51] found that the use of pain medication prior to surgery, younger age, female, lower socioeconomic status (education and household income), high health-seeking behavior, and presence of substance abuse, insomnia, or mental health disorders prior to surgery were all significant in predicting chronic opioid use after surgery. However, it is likely that a combination of these variables may provide a greater predictive value for determining the likelihood of chronic opioids following surgery.

A recent study by Cook[52] showed that nearly 40% of THA patients do not fill their opioid prescriptions after surgery and proposed that strong consideration should be given to alternative pain control methods. It has been previously documented that many patients who fill an opioid prescription do not use any pills[16], thus the true number of patients who require opioids following surgery is likely lower than the number of patients who fill a prescription. Ideally, opioid prescriptions after surgery should balance adequate pain management against the duration of treatment. Although their analysis did not include THA, Scully[46] proposed that the optimal length of opioid prescriptions for common orthopedic procedures is around 6 to 15 d. This is corroborated by the findings of our study as opioid consumption quantity reached below the preoperative levels between days 15-30 postoperatively.

This study is not without limitations. The retrospective nature of this study has the potential to introduce inherent bias. The study population was majority female and age 65 years or older which causes inherent selection bias. Both the opioid and pain surveys that were administered relied on selfreporting by the patients. Due to the nature of the self-reported survey, opioid dependence could be undetected in our study cohort. All patients in this study underwent THAthe direct anterior approach by a single surgeon, thus our results may not be generalizable to patients who undergo THAother surgical approaches. Additionally, we excluded any patients who underwent revision of their primary implant or were hospitalized due to any postoperative complications. These patients may be the heaviest postoperative users of opioids due to a difficult and prolonged recovery resulting in higher pain intensity. Indeed, most patients included in the present study had a LOS of less than two days, and further analyses may benefit from addressing how lengthened in-patient stays affect VAS and the subsequent prescription of opioids postoperatively. In addition, the pain threshold of each patient is different making the generalizability of our results relatively difficult. Although we accounted for all non-THA related pain indications, we could not quantify all possible pain events after surgery that could necessitate prescription opioid therapy. Theoretically, a patient could have obtained an opioid prescription after undergoing THA for an issue unrelated to their orthopedic procedure. Patients who have pre-existing psychiatric conditions, anxiety, and/or fear of pain may confound the data, as they are unlikely to show improvement in pain, regardless of pain score. We did not quantify both opioid and non-opioid oral analgesic use such as meloxicam and aspirin according to oral morphine equivalent or collect the duration of preoperative opioid use. In addition, our analysis of PO opioid medication did not take into account IV opioids received perioperatively. This study only considered opioid intake; therefore, analgesics consumed by patients that may reduce the need for opioid intake could have possibly skewed the results. Furthermore, while VAS scores may be generalizable, an individual’s immediate post-operative opioid consumption is dictated by subjective measures such as anesthesia type could introduce confounding variables that are difficult to quantify[53]. Lastly, we did not account for patients who may have had unreported adverse effects (constipation, nausea, vomiting, hypotension,) due to opioid consumption and stopped their intake during the postoperative periods evaluated in this study. Future investigations comparing multiple surgical approaches for THA and including patients from different regions of the country and various parts of the world would help further elucidate our findings. Despite these limitations, the results presented can aid surgeons’ opioid prescribing patterns based on their patients' reported pain levels following THA.

CONCLUSlON

All patients experienced significant pain relief from having undergone THA. The average postoperative opioid consumption decreased below preoperative opioid consumption status between days 15-30 postoperatively. This decline in opioid consumption was associated with a relative VAS pain score of 3.15. Our results should be used to appropriately guide opioid prescribing patterns and set patient expectations regarding expected pain management following THA. This will not only give patients a baseline to reference during their recovery but also limit redundant billing expenses related to unnecessary prescription of medication and avoidable outpatient visits due to post-operative pain. However, without further research that considers other patient factors that influence pain severity, our understanding of the independent impact of pain on opioid consumption after THA remains uncertain.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the association between the quantity of opioid consumption in relation to visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores both pre- and postoperatively in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty (THA). The amount of opioids prescribed after orthopaedic procedures vary widely in the literature, and only a few established guidelines exist that have standardized acceptable duration and magnitude of opioid use. Our findings showed that patients ceased to depend on opioids between postoperative days 15-30 compared to their preoperative consumption status, which correlated to a mean VAS pain score of 3.15. This information can be used to set patient expectations and allows surgeons to tailor their prescribing habits based on pain intensity reported by their patients.

But how do you suppose we can manage to live till summer comes round again? Do not be anxious about that, said the girl; if you will only marry me all will be well

Research motivation

Over the past few decades, the number of opioids prescribed to manage patients with chronic noncancer related pain such as osteoarthritis has dramatically increased[16,18,30-33]. This reported rise carries substantial implications for orthopedic surgeons, as patients who undergo orthopedic procedures are prescribed more opioid medications on average than patients of most other specialties[13]. The impact of opioids has gained significant clinical and research interest given their potential to prognosticate postoperative outcomes and patient satisfaction. Recent evidence now suggests that opioids provide no additional benefits compared to non-opioid medications such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen to manage pain associated with osteoarthritis and have higher rates of adverse events[34-38]. Additionally, previous studies have also reported that patients who used more opioids postoperatively experienced less satisfaction and greater pain intensity irrespective of the procedure type[8,9]. Therefore, gaining a better understanding of the relationship between opioid use and pain is essential given the shifting emphasis placed upon health safety and quality. The findings of the present study not only demonstrate that all patients achieve significant pain relief following THA, but that average postoperative opioid consumption decreased below preoperative consumption by days 15-30 postoperatively.

Research objectives

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the association between the quantity of opioid consumption in relation to VAS pain scores both pre- and postoperatively in patients undergoing primary THA. We hypothesize that both opioid consumption and VAS pain scores will decrease for all patients following surgery when compared to their preoperative status.

Research methods

As part of our institutional standard of care, patients were preoperatively registered for an electronic patient engagement application (EPEA; Force Therapeutics, New York, NY) by clinical care coordinators at the time of surgical scheduling. The EPEA is a mobile and web-based technology that wirelessly delivers digital patient reported outcome questionnaires to patients at pre-defined time intervals. This application was used to collect VAS pain scores and quantity of opioid consumption daily for seven days before surgery through the first 30 postoperative days.

Research results

Our findings showed that patients ceased to depend on opioids between postoperative days 15-30 compared to their preoperative consumption status, which correlated to a mean VAS pain score of 3.15.

Research conclusions

The collected baseline patient demographic data included gender, age, body mass index (BMI; kg/m), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, race, smoking status, length of stay (LOS; days), and surgical time (minutes). LOS was determined by calculating the difference between the time of admission and discharge following surgery. Surgical time was derived from calculating the time difference between the initial skin incision and the completion of skin closure. All demographic data were extracted from our institution’s electronic data warehouse (Epic Caboodle. version 15; Verona, WI) using Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio 2017 (Redmond, WA).

Research perspectives

All patients receive similar postoperative multimodal analgesia medications during the immediate post-anesthesia care unit period, on the surgical floor, and discharge. Postoperative pain management was accomplished using mostly non-narcotic medications. Patient-controlled analgesia, as well intravenous opioid administration, was strongly discouraged, except in rare situations of breakthrough pain when alternatives had been exhausted. Additionally, patients receive a prescription of aspirin 81 mg twice daily as the primary deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, which also has analgesic effects as part of our multimodal approach. Following discharge, patients are assessed for adequate pain control (and severity) at multiple time pointstelephone and during scheduled follow-up visits.

FOOTNOTES

Singh V, Tang A, and Bieganowski T write the manuscript; Singh V collected the data; Singh V and Anil U did the analysis; Macaulay W did the edits. Schwarzkopf R and Davidovitch RI are responsible for conceptualization and manuscript editing.

The present study retrospectively analysed de-identified data for institutional quality improvement initiative and was therefore exempted from human-subjects review by our Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent was not needed for this study. This was a quality improvement initiative at our institution.

Singh V, Tang A, Bieganowski T and Anil U have nothing to disclose. Macaulay W holds stock options in OrthoAlign. Schwarzkopf R is a paid consultant for Smith & Nephew and Intellijoint. He also has stock options in Gauss Surgical outside the submitted work. Davidovitch RI is a paid consultant for Radlink, Schaerer Medical, Exactech, and Medtronics.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

2.Miller:While not noble, millers30 did have some rank in society as their job, grinding flour, was needed by all. In the Industrial Revolution, mills went from manual labor31 in terms of hoisting32 the flour bags to an early form of automation (Hagley) powered by water that hoisted33 the bags. By the mid16 1800s used a water turbine (Hagley 16). The fact that the miller is so poor indicates hard times, possibly caused by a famine, a war, or even the Industrial Revolution (perhaps the mill is out of date). The miller can not even make a living doing his normal job. In the 1812 version, the miller is simply poor and not sliding into poverty (Zipes, Brothers, 176). Return to place in story.

United States

Vivek Singh 0000-0003-2450-1785; Alex Tang 0000-0001-7086-4355; Thomas Bieganowski 0000-0002-1566-7962; Utkarsh Anil 0000-0003-1807-1926; William Macaulay 0000-0003-2684-0676; Ran Schwarzkopf 0000-0003-0681-7014; Roy I Davidovitch 0000-0003-4083-4205.

But as the day wore on and the road mounted higher, that little core of self-control grew smaller and smaller, and finally, on a heart-stop-ping grade southwest of Barstow, California, it vanished altogether.,,,,。

Wu YXJ

Ah, ah! said he; I see then how thou wouldst cheat me, thou cursed woman; I know not why I do not eat thee up too, but it is well for thee that thou art a tough old carrion32. Here is good game, which comes very quickly to entertain three ogres of my acquaintance who are to pay me a visit in a day or two.

On going to the first jar and saying, Are you asleep? he smelt30 the hot boiled oil, and knew at once that his plot to murder Ali Baba and his household had been discovered

A

Wu YXJ

World Journal of Orthopedics2022年8期

World Journal of Orthopedics2022年8期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Rates of readmission and reoperation after operative management of midshaft clavicle fractures in adolescents

- Bilateral hip heterotopic ossification with sciatic nerve compression on a paediatric patient-An individualized surgical approach: A case report

- Quantitative alpha-defensin testing: ls synovial fluid dilution important?

- Effect of pelvic fixation on ambulation in children with neuromuscular scoliosis

- Epidemiology of pelvic and acetabular fractures across 12-mo at a level-1 trauma centre

- Risk modeling of femoral neck fracture based on geometric parameters of the proximal epiphysis