A neuron’s ambrosia: non-autonomous unfolded protein response of the endoplasmic reticulum promotes lifespan

Stefan Homentcovschi,Ryo Higuchi-Sanabria

The ability to protect cellular components in the face of deleterious conditions,such as exposure to chemical poisons,damaging radiation,or excessive heat,is crucial to organismal viability. Several compartmentalized stress response pathways have evolved to mitigate damage and increase cellular fitness in such environments,including the unfolded protein response of the endoplasmic reticulum (UPRER). The UPRERserves a critical protective role by promoting proteome integrity and lipid homeostasis while preventing the accumulation of damaged proteins and protein aggregates. The ability to mount an effective UPRERis a key determinant of organismal lifespan and stress resistance,however,as with other stress responses,it has been shown to decline markedly during the aging process. This leaves the proteomes of aged animals susceptible to dysregulation and dysfunction,which in turn further contributes to an accelerated aging process,development of age-associated pathology,and proteotoxicity (Higuchi-Sanabria et al.,2018).

Multicellular organisms are faced with the additional challenge of coordinating effective stress responses across multiple tissues and cell types. Cell-nonautonomous communication of UPRERhas been well documented in the nematodeCaenorhabditis elegans,in which activation of the UPRERspecifically in neurons has been shown to increase ER stress tolerance and lifespan by inducing UPRERactivation in the periphery. More specifically,panneuronal overexpression of a gene encoding one of the UPRERtranscription factors,splicedxbp-1(xbp-1s),triggers the release of small clear vesicles from the signaling neurons. Presumably,the released neurotransmitters and/or biogenic amines trigger intestinalxbp-1splicing by the endoribonuclease IRE-1 and subsequent activation of UPRERthrough a cellnonautonomous mechanism. In these animals (referred to as neuronalxbp-1sanimals),the age-related decline in UPRERactivation is abrogated and robust neuronal and intestinal transcription of UPRERtargets continues even in aged animals (Taylor and Dillin,2013).

Two distinct and independent arms of UPRERhave been identified to contribute to the lifespan extension and stress resistance that are experienced by neuronalxbp-1sanimals: a protein homeostasis and lipid homeostasis arm (Daniele et al.,2020). The activation of genes encoding UPR-specific chaperones supplement ER-resident chaperones to provide additional protein folding machinery in times of mild to moderate unfolded protein stress. Neuronalxbp-1sdirectly induces the expression of these chaperones in peripheral tissues and maintains their expression throughout age,resulting in increased stress resistance and lifespan (Taylor and Dillin,2013). Traditionally,UPRERtargets also include components important for ER-associated degradation and ER-specific autophagy,but whether these processes are also activated downstream of cues from neuronalxbp-1soverexpression is yet to be determined. However,a recent study has found that there is in fact an increase in the transcription of lysosomal genes,which results in increased lysosomal abundance and lysosomal acidity (Imanikia et al.,2019b). Surprisingly,the beneficial effects of the lysosomal expansion are independent of autophagy,and rather promote protein homeostasis through increased clearance of damaged and aggregation-prone proteins from the cell. Furthermore,knockdown of the lysosomal lysine and arginine transporter,laat-1,results in decreased lifespan and a significant increase in sensitivity to ER stress,also independent of general autophagy (Higuchi-Sanabria et al.,2020a). These studies shape lysosome-ER communication and interactions as pivotal in organismal homeostasis and uncover an intriguing regulatory link between two seemingly opposing metabolic hubs of the cell.

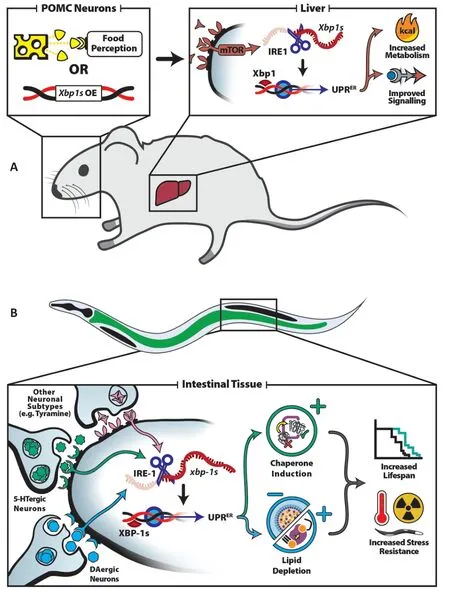

Beyond protein homeostasis,neuronalxbp-1spromotes the activation of a metabolic arm of UPRER,which results in upregulation of lysosomal lipases,desaturases,and lipophagy,which together contribute to the significant reduction in total body fat seen in these animals. This lipid depletion involves conversion of stearic acid into oleic acid by the upregulated intestinal ∆9 desaturase FAT-6,which has been demonstrated to increase longevity inC. elegans(Imanikia et al.,2019a). These processes are coincident with ER expansion and remodeling,and hyperactivation of a lipophagy machinery,which are also necessary and sufficient to promote the beneficial effects of UPRERactivation (Daniele et al.,2020). Interestingly,the former study showed that changes in lipid homeostasis are sufficient to improve protein quality control. Specifically,oleic acid supplementation was sufficient to decrease toxicity associated with ectopic polyQ expression (Imanikia et al.,2019a). However,lipophagy-mediated effects had little to no change in sensitivity to protein misfolding stress,suggesting the coordination of the protein and lipid homeostatic arms of UPRERare complex and likely highly specific to which processes are activated (Daniele et al.,2020).A similar paradigm of cell-nonautonomous communication is seen in mammalian systems,where UPRERinduction in hypothalamic proopio-melanocortin (POMC) neurons of mice induces metabolic changes in the periphery (Figure 1A). Specifically,elevated levels of Xbp1 in mouse POMC neurons induceXbp1splicing by IRE1 and UPRERactivation in the liver,which ultimately results in improved glucose levels,increased metabolic rate,and protection against obesity and diabetes. These effects are dependent on increased cellular sensitivity to leptin and insulin,which results from UPRERmediated protection of the POMC neuronal proteome (Williams et al.,2014). Furthermore,POMC neurons have been shown to promoteXbp1splicing in the liver during sensory food perception,which proactively maintains organismal homeostasis by priming the liver for digestion of incoming nutrients. This suggests that cell-nonautonomous UPRERactivation has important implications for organismal homeostasisin vivo,and is not merely some artificial system activated by exogenous genetic manipulations (Brandt et al.,2018). Indeed,the direct conservation of these signaling mechanisms across phyla suggests that they are of critical importance to organismal fitness,and that an improved understanding of their mechanistic subtleties and cellular consequences may have significant implications on the study of ER-related pathologies and aging.

To this end,Higuchi-Sanabria et al. (2020a) performed a neurotransmitter screen inC. elegansin an effort to identify neuronal subtypes involved in cell-nonautonomous communication of UPRERto the periphery. This study identified two neuronal populations as being critical in the neuron-to-periphery communication of ER stress: serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons. Perhaps most intriguingly,this work showed that not only can the protein homeostatic and metabolic roles of UPRERbe separated,but unique neuronal circuits exist to elicit these divergent responses. Specifically,overexpression ofxbp-1sin serotonergic neurons was sufficient to drive chaperone induction in the periphery to promote increased resistance to protein misfolding stress. However,serotonergicxbp-1sfailed to promote the lipid depletion found in previous studies of neuronalxbp-1ssignaling. Instead,dopaminergicxbp-1swas found to be sufficient to drive lipophagy- mediated lipid depletion,yet failed to drive protein homeostasis. Thus serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons,although both driving cell-nonautonomous activation of UPRERthroughxbp-1sin the periphery,ultimately initiate two distinct transcriptional programs,the coordinated efforts of which provide the beneficial effects on organismal lifespan and stress resistance conferred by pan-neuronalxbp-1soverexpression (Figure 1B) (Higuchi- Sanabria et al.,2020a).

Figure 1|Cell-nonautonomous UPRER signaling mechanisms in mice and C. elegans.

Yet to be determined is how serotonergic and dopaminergic signaling of stress fits into the broader context ofC. elegansneurobiology. Although serotonin and dopamine are required for the cell-nonautonomous communication of UPRERseen in this model,it is unclear whether their endogenous communication is dependent on the release of other neurotransmitters. Indeed,other neuronal cell types have been implicated in peripheral communication of UPRERinC. elegans. Expression ofxbp-1sin RIM and RIC neurons,which are involved in tyramine communication,has been shown to induce intestinal UPRERactivation and altered feeding behavior (Özbey et al.,2020). Additionally,glial cells have also been implicated in intestinal induction of UPRER:xbp-1soverexpression in a subset of four astrocyte-like glial cells increases lifespan and organismal resistance to ER stress (Frakes et al.,2020),showing evidence that neuronal cells are not the only cells important for driving non-autonomous UPRER. Therefore,it is critical to further characterize and map the complex neuronal circuits and cellular mechanisms involved in cell-nonautonomous UPRERtransmission. Do neurons or glia directly and independently relay a signal to the periphery,or is there a concerted and coordinated effort? Which neural subtypes are actually important for sensing ER stress? In addition,the neuronal subtypes involved in mediating lysosomal changes in the periphery have yet to be identified. Are serotonergic,dopaminergic,or tyraminergic neurons involved or are there still unidentified neuronal subpopulations critical for initiating a lysosomal response?

Beyond mapping the neuronal circuitry involved in initiating the transmission of stress,further work is necessary to identify how exactly peripheral cells receive and respond to these cues. While tyraminergic receptors have been identified directly in the intestine (Özbey et al.,2020),whether serotonin or dopamine cues are received directly by peripheral tissue or relayed through an additional cell-type is unclear. In addition,it is intriguing how the same tissue - the intestine - responds to signals from serotonergic neurons and dopaminergic neurons in different ways,despite the transcription factor,XBP-1s,being shared in both responses. This begs the question of how one cell can coordinate two different responses solely based on the source of the signal received. Finally,it should be noted that there exist some circumstances in which hyperactivation of UPRERcan be detrimental,and how a cell is able to identify such situations and differentiate between beneficial and detrimental stress responses is not well understood. An ongoing challenge will be to integrate these distinct and diverse signaling modalities - and those still yet to be identified - into a single,cohesive paradigm of organismal stress response coordination.

We greatly appreciate the funding support provided by the National Institute of Aging through grant 1K99AG065200-01A1 to RHS.

Stefan Homentcovschi,

Ryo Higuchi-Sanabria*

Department of Molecular & Cellular Biology,University of California,Berkeley,CA,USA

*Correspondence to:Ryo Higuchi-Sanabria,PhD,ryo.sanabria@berkeley.edu.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8936-5812(Ryo Higuchi-Sanabria)

Date of submission:February 1,2021

Date of decision:March 3,2021

Date of acceptance:April 13,2021

Date of web publication:July 8,2021

https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.317967

How to cite this article:Homentcovschi S,Higuchi-Sanabria R (2022) A neuron’s ambrosia: non-autonomous unfolded protein response of the endoplasmic reticulum promotes lifespan. Neural Regen Res 17(2):309-310.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal,and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License,which allows others to remix,tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially,as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Rajesh H. Amin,Auburn University,USA.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- A Drosophila perspective on retina functions and dysfunctions

- Celeboxib-mediated neuroprotection in focal cerebral ischemia: an interplay between unfolded protein response and inflammation

- Pramipexole,a dopamine D3/D2 receptor-preferring agonist,attenuates reserpine-induced fibromyalgia-like model in mice

- Effects of delayed repair of peripheral nerve injury on the spatial distribution of motor endplates in target muscle

- Neurorehabilitation using a voluntary driven exoskeletal robot improves trunk function in patients with chronic spinal cord injury: a single-arm study

- Gene and protein expression profiles of olfactory ensheathing cells from olfactory bulb versus olfactory mucosa