梦蝶:托尼奖话剧登上歌剧舞台

司马勤

对于很多艺术家来说,后疫情时代的演出日程极度两极分化,从“饥荒”到“盛宴”——要么少得可怜,要么一下子多得要命。今年3 月,作曲家黄若临危受命,亲自指挥他的新歌剧《山海经》(Book of Mountains & Seas )的纽约首演。这部作品重新审视与呈现了中国的上古神话,作曲家的搭档是木偶艺术家兼设计师巴索尔· 特威斯特(Basil Twist)。与此同时,华盛顿国家歌剧院在肯尼迪中心举行了黄若的另一部新歌剧《裂痕》(TheRift )的世界首演,编剧是托尼奖得主黄哲伦。6 月,黄哲伦与作曲家盛宗亮合作的歌剧《红楼梦》,在2016 年世界首演及2017 年中国巡演后,重返旧金山歌剧院舞台。

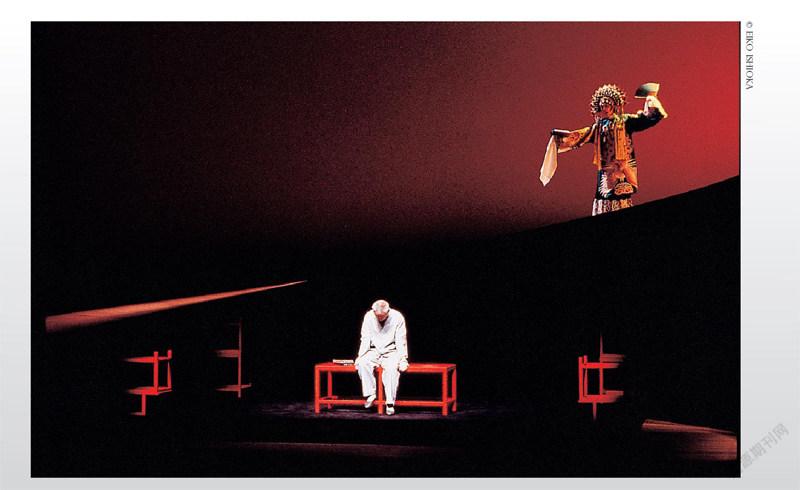

然而,上述的这些制作只能算是“序曲”。也许今年夏季最令人期盼的,是美国圣达菲歌剧院(Santa Fe Opera)即将举行的歌剧《蝴蝶君》(M.Butterfly )的世界首演。该剧由黄若谱曲,编剧黄哲伦改编自自己最具代表性的同名获奖话剧。故事把普契尼引进百老汇——通过20 世纪六七十年代背景下一位法国外交官与一位中国京剧旦角演员之间多年的情结解构并反转普契尼的《蝴蝶夫人》。话剧版于1986 年10 月完成,1988 年2 月在华盛顿国立剧院首演,35 年后该剧的歌剧版得以登上舞台犹如水到渠成。事实上,这个计划在过去十年里一直进展得一波三折、断断续续——包括原定的世界首演由于疫情原因从2020 年延期至今。

虽然因疫情停摆的工作再次繁忙起来,两位艺术家仍然愿意腾出时间来一起讨论他们的最新作品和一直以来的多项合作,以及应对过去两年半里周围一切的心得。

你们俩今年都挺忙碌。

黄若:嗯,但这不代表我的创作量突然增加或工作节奏飞快提速。你知道的,毕竟我们经历了一次大疫情。其实,某些项目已经酝酿很久了。

黄哲伦:剧场演出相对较晚才恢复,但我正忙着几部电视剧的制作。当然也有歌剧创作。每个领域都有不同的防疫限制措施。项目成功与否,效果参差。

《蝴蝶君》这部歌剧酝酿很久了。现在再次聆听已经写好的音乐,有什么感想?

黄若:你知道吗?今年年初,圣达菲歌剧院邀请我们参加了一场在古根海姆博物馆举行的工作坊演出。他们问我:“歌剧院现存的《蝴蝶君》总谱分谱还需要修改吗?”我想了想,感觉这些写好的音乐在疫情期间像被时间凝固了一样,现在只需要“解冻”了。

有没有大改动?

黄若:大的改动谈不上。但现在的世界已迥然不同了。无论是精神还是肉体,我们已到了另一个层面。当你欣赏一部交响乐或舞台制作时,完全可以感受出它是疫情前还是疫情后的成品。太多疫情前的作品现在看起来过分和谐欢聚(Kumbaya -happy),或只是为了艺术而艺术——这显得尤为肤浅,或者说与我们的经历脱节。疫情的确改变了我们对事物的看法——最起码,我是这样。但是,《蝴蝶君》是永恒的,不会为了迎合新兴潮流而有所改动。

黄哲伦:在接近歌剧尾声,当外交官伽里玛(Gallimard)启程回到巴黎时,我们添加了一首新的咏叹调。我和黄若一起合作过《蝴蝶君》与《一个美国士兵》,他两度在谱曲的过程中,请我再写一段咏叹调唱词,用于将故事与人物带入最后的情感高潮。这两部歌剧中的最后增添部分都成为我最喜欢的段落。

《一个美国士兵》是你们首部合作的歌剧。作品是怎样诞生的?

黄若:2013 年初, 我收到了华盛顿国家歌剧院艺术总监弗朗切斯卡· 赞贝罗(FrancescaZambello) 的电话, 她刚刚成立了华盛顿国家歌剧院的“ 美国新歌剧计划”(American OperaInitiative)。她有意委约一部时长60 分钟的歌剧,一是问我有没有故事题材,二是问我心目中有没有理想的编剧?她提出一个条件:歌剧讲述的必须是一则美国故事。我跟哲伦提出这个歌剧计划项目,他提议写陈宇晖(Danny Chen)的故事。当时,我们曾讨论过改编《蝴蝶君》,但是《一个美国士兵》却成为我们合作的首部作品,并在2014 年首演。

黄哲伦:陈宇晖是美籍华裔美军士兵,不幸饱受其他士兵对他的种族歧视且被欺凌至死。我曾联络过他的家人,有意构思一部话剧。我们最终把这个故事搬上了歌剧舞台的其中一个原因是,这个故事情节分明,毫不拖泥带水,所涉及的道德议题——谁对谁错——也十分清晰。但歌剧可以把人物与故事升华到更深刻的境界。把这一类现实故事编写成歌剧,再合适不过。

过了几年,你们把《一个美国士兵》原来的一幕剧扩充了。

黄若:圣路易斯歌剧院(Opera Theatre of St.Louis)委约了这个增长版,并于2018 年首演。《一个美国士兵》本来是一部相对小巧的纪实歌剧,哲伦为此收集了很多资料。我们把原来的一幕扩展成二幕,让角色有更多发展空间,但基本上情节没有什么大改动。在此前的华盛顿首演时,我们被有些乐评指称为“不和谐”(dissonant)——这个形容词不只限于音乐风格,我们更被指控为“反美国”(anti-American)。在奥巴马担任总统期间,种族歧视这个议题——尤其是针对亚裔与美籍亚裔的种族歧视——从没有被提及过。人们没听说过这些,不相信并且对此也毫不关心。因此,我们就像两颗不和谐的石头丢进平静的湖水中。但在圣路易斯演出时,已经是特朗普执政时期,国家出现多重分歧。乐评描述我们的这部作品“令人心痛”以及“强大有力”。短短四年,我们从“不和谐”变得“强大有力”。

听起来,你们两人都是对歌剧艺术情有独钟。

其实,你们是怎样认识的?

黄若:我曾为哲伦的一部早期作品《铁轨之舞》(The Dance and the Railroad )的復排谱曲,这部作品后来参加了2012 年首届乌镇戏剧节。这次演出也包括了我亲自演唱的段落,于是我们也开始谈论歌剧。当时,我已经创作了一部用中文演唱的歌剧,希望接着探索英文歌剧。我们从哲伦现有的舞台剧讨论起,这样要比从零开始创作容易得多。我当然知道《蝴蝶君》。那是我在美国观赏的首部话剧,一直以来我都梦想为它写部歌剧。提及《蝴蝶君》时,我做好了心理准备——我猜想哲伦也许会说“啊,已经有人着手准备歌剧版了”,但他说“没有”。于是我们立刻决定,把《蝴蝶君》改编为歌剧。

黄哲伦:我完全不记得这部分的讨论了。我大概没有留心,直至某个歌剧院对这部作品感兴趣。

我的初衷是创作《蝴蝶君》的音乐剧,但是当年我不认识任何作曲家。这个故事解构自《蝴蝶夫人》,普契尼的音乐与剧中情节交错,话剧舞台上的中国戏曲部分都是重新创作的。还有,话剧版本来聘请了约翰· 德克斯特(John Dexter)执导,他是大都会歌剧院多年来的驻院导演。我想,命中注定的,《蝴蝶君》必然会有一个“音乐版”。

为什么等了这么久?

黄哲伦:我可以找个歌剧院毛遂自荐,并且跟他们说:“请帮我物色一位作曲家。”当然有这个可能。但是,作为编剧,去启动一个基于文学作品的音乐项目,还是缺乏相应的主导能力。除非有一位作曲家觉得,这一文本具有改编成歌剧的必要性,否则整个计划不可能往前推进。

那么,现在终于是《蝴蝶君》歌剧诞生的时机了。

黄哲伦:2017 年,这部话剧在百老汇重演,导演是朱丽· 泰莫(Julie Taymor),为我提供了修改剧本的机会。一方面我添加了当年法庭诉讼的细节,另一方面也增添了反映自1988 年以来,我们对于两性定义的蜕变。我还加入了《梁山伯与祝英台》的戏曲部分,这样既丰富了性别平衡,也在普契尼音乐以外,增添了亚洲的音乐元素。我在歌剧剧本保留了《梁祝》的部分,又结合了新剧本的一些材料,以及黄若喜欢的1988 年原版的细节。

黄若:宋丽伶是剧中那位美丽动人的戏曲演员,在歌剧中我选用了假声男高音(countertenor)。而伽里玛是男中音——不是男高音——他内向,并不花哨!普契尼《蝴蝶夫人》中的“哼吟合唱”演变为讨论这宗丑闻的“流言蜚语”合唱。还有,我把普契尼序曲中的某些主题注入到京剧旋律动机里。

黄哲伦:将《蝴蝶君》改编为大型歌剧最棘手的部分,是这个故事本身只围绕着两个人发生。其他角色进进出出,但伽里玛差不多从头到尾都在舞台上。这对于话剧演员来说属于挑战,但对于歌剧演员来讲就真得太困难了。就歌剧架构而言,咏叹调很容易安排,比较艰难的是选择适当的地方插进二重唱、三重唱、合唱等,力图使音乐更多元化,同时也能让独唱演员有机会离开舞台休息一会。

《蝴蝶君》本来应该在2020 年首演,现在延迟至今年8 月。但是,你们两人在此其间又创作了另一部歌剧。可以说说这部作品的来龙去脉吗?

黄若:那又是源于弗朗切斯卡的另一次来电,她再次向我委约独幕歌剧,目的是为了庆祝肯尼迪中心的50 周年大庆。完整的项目名称为《石刻的字句》(Written in Stone ),而每一组主创必须选择位于华盛顿首都的纪念碑或建筑为主题进行创作。

我选择了越战退伍军人纪念碑,部分原因是我知道哲伦跟纪念碑的建筑师林璎(Maya Lin)是好朋友,或许哲伦会有兴趣深入探讨这个主题。陈宇晖的故事是只围绕着主角一个人的挣扎,哲伦认为《裂痕》应该增加不同角色与观点。他最令人佩服的一笔,是在作品中展示了越南裔在美国的经历:一个南越士兵的遗孀质问,为什么丈夫的名字没有刻在纪念碑上。这个故事包含了很多层次。

黄哲伦:这显然是一个更复杂更微妙的故事,但之前的《一个美国士兵》让我们建立了信心去处理一个比较当代的主题,作品涉及的道德议题比《一个美国士兵》更繁复更有层次。然而《裂痕》更短,而且一共只有四位演员。

黄若:演员阵容虽然有限制,但每人演出的角色数的可能性却是无限的。我特别喜欢哲伦的话剧《黄面孔》(Yellow Face ):在短短的时间内,一位演员扮演了多个截然不同的角色。《裂痕》的演员中有白种人、亚裔和非洲裔,他们扮演很多种类的人物。我们希望尽可能地具有包容性。

黄哲伦:《一个美国士兵》中也有演员负责两个角色,但在《裂痕》里,每一位都要扮演不同角色。难度最高是女高音Karen Vuong,她饰演建筑师林璎,但转过来又要饰演一位越南裔女生。

你们创作《裂痕》时,正逢新冠疫情影响全球,一切都停滞了。当时的环境有没有影响到你们的创作?

黄若:2020 年3 月,我什么都写不出来。截稿的日子迫在眉睫,我们也不确定演出能否如期进行。

我跟哲伦通电话,他说:“你看,我们所在的国家现在社会不公,亚裔被仇视,国家分裂的程度犹如越战时代。”他的一句话给了我动力,给了我斗志。

黄哲伦:当年的不少艺术作品帮助国家与人民治愈了历史的裂痕,我深受触动。

詹姆斯·羅宾逊(James Robinson)是华盛顿歌剧院《裂痕》的导演,也是圣路易斯《一个美国士兵》的导演。他也将执导圣达菲歌剧院的《蝴蝶君》。2014 年,罗宾逊是黄若歌剧《中山逸仙》美国首演的导演。这么多年的合作有什么帮助?

黄若:在我的心目中,圣达菲才是《中山逸仙》的世界首演,因为我最早的版本是为西方交响乐队写的(2011 年,北京国家大剧院本来的演出延期;而在香港的演出则用了我另外写的民乐团版本)。

圣达菲也是我首次接触欧美歌剧院,首次跟一位富有经验的西方歌剧导演合作。他把歌剧中的每一个元素都融合起来,旨在为服务角色、戏剧、音乐张力的需要服务,而不会受政治因素的干扰。就在那一刻,我领略到,歌剧就是我的使命,以及我的身份、我要继续走的路。

黄哲伦:我们合作的这些年来,我目睹了黄若在歌剧创作方面的成长,尤其是他为人声谱写优美旋律的能力。我一开始不确定他是否愿意写富有调性的音乐,但他的早期作品感觉上很“管弦乐化”。

从《中山逸仙》起,他建立了更大的信心与勇气,写出名副其实、具有原创性的富有调性、抒情的旋律。

你们俩也开拓了一个独特的主题门类,尤其是与亚洲有关的作品。

黄哲伦:几个月前,林肯中心重新启动了“美国歌集”(American Songbook)音乐会系列,其中一场就是黄若的声乐作品专场。全部曲目——包括《蝴蝶君》的咏叹调——都是根据亚裔经历的真人真事创作的。我不肯定我们有没有刻意锁定目标,记录美国亚裔历史,但是,我们的确有这种倾向。

黃若:我还写过两部跟美国亚裔主题没有关系的歌剧,它们在风格与主题上也不一样。《惊园》(Paradise Interrupted )是一部装置歌剧(installationopera),艺术家马文的动态折纸雕塑犹如一个黑色的花园, 看起来像中国传统的剪纸。然后就是《山海经》。作品的起源是哥本哈根新艺术(ArsNova Copenhagen)合唱团指挥保罗· 希里尔(PaulHillier)。他对我说:“我想委约你创作一部听起来像你自己歌唱的作品。”从来没有人向我提出过这种要求(大笑)。我认为,歌剧就是歌唱与表演融合的艺术载体。故事有时候具体,有时候抽象。它必须有动态,并运用上多维空间。但是,歌声必须有戏剧性。《山海经》的阵容是12 位歌唱家与两位打击乐手。瓦格纳粉丝们大概会抗议这部作品不算是歌剧,但如今的歌剧就是可以这样。

不过,我一直很清楚,在歌剧院里,我的音乐有很大的机会与威尔第或普契尼的作品同期演出。我希望创作出的作品富有世界性,任何国家的歌剧院都可以制作及演出。但是关于选题方面,我当然会选取与自身有关的主旨与故事,尤其是我身为亚裔与美籍华裔的身份。很少有创作者能够深入探讨自己最关心的故事。正因为我有这些幸运的机会,我就应该做得更多。如果我需要在创作关于孙中山或肯尼迪的歌剧中选择,我当然会选孙中山。至于肯尼迪,很多其他作曲家都可以胜任。

For many artists, the post-pandemic performanceschedule has gone from famine to feast. In March, thecomposer Huang Ruo found himself conducting theNew York performances of his Book of Mountains &Seas , a retelling of the Chinese creation myth directedby puppeteer/designer Basil Twist, at the sametime his opera The Rift , with a text by Tony Awardwinningplaywright David Henry Hwang, had its worldpremiere at the Washington National Opera. In June,Hwang saw the revival of Dream of the Red Chamber,his 2016 piece with the composer Bright Sheng, atSan Francisco Opera celebrating its return to thecompanys repertory after its 2017 China tour.

But these were mere prelude. Perhaps the mostanticipated operatic event of the summer is the SantaFe Operas world premiere of M. Butterfly , Huangsoperatic version of Hwangs landmark play. For astory that brought Puccini to Broadway—albeit adeconstruction of Madama Butterfly filtered throughChinese espionage and a French diplomats longtermrelationship with a cross-dressing Peking Operasinger—its operatic retelling 35 years later might seeminevitable, perhaps long overdue. Its actual journey,however, was a decade of fits and starts—not leastbeing a two-year delay since the production was firstplanned for 2020.

The two artists each took a moment from theiragain-busy schedules to discuss their latest work, theirongoing collaboration and how they kept going duringthe past two and a half years.

Youve had a quite a busy year so far.

HUANG RUO: Well, it wasnt like I suddenly wrotea lot more, or a lot faster. We had a pandemic, youknow. Some of these projects had been brewing for along time.

DAVID HENRY HWANG: Live theatre has been a bitlate to come back, but Ive been working on severaltelevision projects. And of course, opera. All thesefields have different Covid protocols and some havebeen more successful than others.

M. Butterfly the opera has been brewing for a while.How did the music sound to you when you came back to it?

HR: You know, when Santa Fe invited us to do aworkshop at the Guggenheim Museum earlier this year,they asked me, “Are the scores we have still valid?” AndI really had to think. Everything Id written had beenfrozen in time, and now I had to start defrosting it.

Did you change much?

HR: Not really. Its a very different world now. Bothmentally and physically were in a different place.Whenever you see a symphony or a stage production,you can usually tell if it was created before thepandemic. Too many things seem either Kumbaya -happy or art-for-arts-sake—you know, superficial, orunrelated to our experience now. The pandemic reallychanged our—and least my—way of seeing things. ButM. Butterfly needed to be timeless, not just changed tobe the flavor of the month.

DHH: One of the things thats new is an aria towardthe end, when Gallimard goes to Paris. In both M.Butterfly and An American Soldier , Huang Ruo gotto the point where he wanted one more emotionalclimax, and he came back to me for a new aria. Andboth times, that wound up becoming my favoritemoment in the opera.

An American Soldier was your first opera together,how did that come about?

HR: I got a call from Francesca Zambello, whod juststarted the American Opera Initiative at WashingtonNational Opera. She was interested in commissioninga 60-minute opera and asked me (1) Do I have anystory, and (2) Do I have any librettists in mind. Therewas only one condition: the story had to be American.So I mentioned this to David and he suggested thestory of Danny Chen. David and I had already talkedabout M. Butterfly, but American Soldier became ourfirst opera collaboration in 2014.

DHH: Danny Chen was a Chinese-American in the USArmy who was basically hazed to death by his fellowsoldiers. Id been in touch with the family and had beenthinking about writing a play. One reason we ended upwriting it as an opera was that the story didnt seem tohave much ambiguity. The moral issues involved—whowas right and who was wrong—seemed pretty clear.Opera is well-suited to those kind of stories.

You also turned the one-act into a full-length showa few years later.

HR: Opera Theatre of St. Louis commissioned alonger version, which they premiered in 2018. AnAmerican Soldier was originally a very compact docuopera,where David had done a lot of research. Weexpanded it to give more room for the characters todevelop, but it was fundamentally the same show.In Washington, we had been called “dissonant,” andnot just musically. David and I were basically accusedof being anti-American. While Obama was president,racism—particularly toward Asians and Asian-Americans—was never discussed. People hadnt heardof it, didnt believe it, and didnt care. So we weretwo dissonant rocks thrown in a peaceful lake. In St.Louis, when Trump was in office, there was so muchdivisiveness in our country. Critics called our show“heart-wrenching” and “powerful.” In four years, wewent from “dissonant” to “powerful.”

It sounds like a strong meeting of operatic minds.How did you first actually meet?

HR: I was writing music for a revival of Davids playThe Dance and the Railroad , which later came to theWuzhen Theatre Festival in 2012. I was singing some ofthe music Id composed for the show and we startedtalking about opera. Id written an opera in Chineseand was looking to explore my American side, so westarted going through his existing plays, since thatwould be easier than creating something from scratch.Of course, I knew M. Butterfly . It was the first play I sawin America and Id wanted to set to music ever since.I was fully expecting him to say, “Oh, someone else isdoing it.” But we settled right then on M. Butterfly .

DHH: I dont remember that part at all, but I probablydidnt start paying attention until an opera companywas interested in staging it. My initial impulse wasalways for M. Butterfly to be a musical, but I didnt knowany composers back then. The story is a deconstructionof Madame Butterfly , with Puccinis music oftencounterpointing the action in the play, and much of theChinese opera music had to be composed. Also, theoriginal director was John Dexter, who was in residenceat the Metropolitan Opera for years, so I suppose M.Butterfly was always destined to be musicalized.

So why did it take so long?

DHH: I suppose I couldve gone to an opera companyand said, “Find me a composer.” Its not impossible.But as a librettist theres no real incentive to initiatea project based on a literary property because itsnot going to move forward until a composer feelscompelled to take it on.

It seems like the time is finally right for M. Butterfly

DHH: There was also a Broadway revival of theplay in 2017 directed by Julie Taymor, where I wentback and rewrote the script both to include moreinformation from the court trial and to reflect howour understanding of gender has evolved since 1988. Ialso included some stuff about the Chinese opera TheButterfly Lovers , which offered both a better genderbalance and an Asian counterpart to Puccini. I keptthe Butterfly Lovers stuff in the opera libretto, whichcombines elements of the new script with some thingsHuang Ruo liked from the 1988 version.

HR: Song Liling, being a Chinese opera singer inthe play, is a countertenor in the opera. Gallimard isa baritone, not a tenor—hes not that flashy! Puccinis“Humming Chorus” in Madame Butterfly is reflected inthe “gossiping chorus” that relates the scandal. Also,Ive reworked some themes from Puccinis Overture asPeking Opera motifs.

DHH: The trickiest thing about adapting M. Butterflyinto a grand opera is that its essentially a twocharacterplay. Other characters come in and out, butGallimard is on stage almost the whole time, which isa challenge for a dramatic actor but really difficult fora singer. As far as operatic structure was concerned,arias were easy. The more difficult part was findingplaces for duets, trios and choruses, both to providesome variation in the music and to give singers sometime offstage.”

In between 2020, when M. Butterfly was originallyscheduled, and its actual premiere in August youwrote another opera. How did that come about?

HR: It was another call from Francesca, who wasagain commissioning short operas, this time tocelebrate the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy Center.The complete evening was entitled Written in Stone ,and each of the creators was asked to write somethingabout a monument in Washington. I choose theVietnam War Memorial, partly because I knew Davidwas a good friend of the architect Maya Lin and maybeit was something hed like to explore. But unlikeDanny Chen, which was one persons struggle, Davidwanted to bring in different characters with differentperspectives. His most brilliant stroke was having acharacter representing the Vietnamese experiencein America: the widow of a Vietnamese soldier whofought on the American side and asked why herhusbands name wasnt included. There were so manylayers involved.

DHH: This was obviously a more complicated andnuanced story, but An American Soldier gave us theconfidence to deal with a relatively recent subjectwith more complexity and many different shades ofmorality—with a shorter length, and only four singers.

HR: We had a limit on the cast, but no limit on thenumber of characters they could play. One of thethings I loved about Davids play Yellow Face wasseeing the same actors playing so many differentcharacters in such a rapid pace. We had Caucasian,Asian and African-American singers playing all sorts ofpeople. We wanted to be as inclusive as possible.

DHH: Wed done a certain amount of doubling inAmerican Soldier , but here it wasnt just doubling buthaving actors playing a full track of characters. Thehardest was probably Karen Vuong, who after gettingthe audiences attention as Maya Lin then had toswitch and play a Vietnamese girl.

When you wrote The Rift , the pandemic hadessentially shut down the world. Did that contextchange what you wrote?

HR: I wasnt able to write anything in March 2020.We had a short deadline, and we werent even sure thepremiere could take place. But I got on the phone withDavid, who told me “Look at where we are as a country,with social injustice and anti-Asian hate. We might be asdivided now as we were during Vietnam.” And that gaveme the energy, the fighting spirit to continue.

DHH: I was also moved by how a piece of art helpedto heal the rifts in our nation back then.

James Robinson, who directed The Rift inWashington, also directed An American Soldier inSt. Louis and is directing M. Butterfly in Santa Fe. Healso helmed the US premiere of Huang Ruos firstopera, Dr. Sun Yat-sen , in Santa Fe in 2014. How hasthat relationship affected the works youve done?

HR: I consider Santa Fe to be the operas worldpremiere, since it used a Western orchestra as Ioriginally conceived it. [The scheduled premiere atthe National Centre for the Performing Arts in 2011was “postponed indefinitely” and the premiere inHong Kong used an orchestra of traditional Chineseinstruments.] It was my first experience with a Westernopera company, and the first time I had an experiencedopera director who could bring every componenttogether to serve the characters, drama and musicalintension with no political distractions. I knew thenthat composing opera was my calling, my identity, thepath I want to continue walking.

DHH: Over the time weve been working togetherI feel Huang Ruo has grown as an opera composer,particularly in his ability to write melodies for thevoice. I dont know if he was afraid to be tonal per se ,but his earlier pieces feel very orchestral to me. Sincethen, hes gained the confidence and courage to writetruly tonal, lyrical lines.

You both also seem to be developing a certaingenre of subject matter as well, particularly withAsian-related subjects.

DHH: Earlier this year, Lincoln Center relaunchedits American Songbook series with an evening ofHuang Ruos vocal music. Everything on the program—including arias from M. Butterfly—was based on trueevents involving Asians. Im not sure we ever set out todocument Asian American history, but its what wevebeen gravitating towards.

HR: I have two operas that are different, both fromthe others and from themselves. Paradise Interruptedwas what we called “installation opera,” createdalongside Jennifer Mas large sculpture of a blackgarden looking like a traditional Chinese papercut.Then we have Book of Mountains and Seas , whichstarted when Paul Hillier, the conductor of the vocalensemble Ars Nova Copenhagen, said “I want tocommission something from you that sounds like theway you sing.” No one had ever said that to me before(laughing ). To me, opera is a place with singing andacting. Sometimes the story is concrete, sometimesits abstract. And it must have movement, a use ofdimensional space. But the drama should be in thevoices. Mountain and Seas uses 12 singers and twopercussionists. Wagner fans would probably arguethat it isnt opera, but its what opera is today.

Im always conscious, though, that in the operahouse my music will probably be placed next to Verdior Puccini. I want to create work thats universal, thatany company can produce and present if they want to.But as for subject matter, I do seek out subjects andstories related to who I am, my identity as an Asianand Asian American. Not all creators out there are ina position to delve into the stories they really careabout, and since I have this opportunity, I should domore. If I had the choice between writing about SunYat-sen or JFK, Id choose Sun Yat-sen any day. Plentyof other composers out there can do JFK.