Trends in prevalence and mortality of gastroschisis and omphalocele in the United States from 2010 to 2018

Parth Bhatt ·Frank Adusei Poku ·Jacob Umscheid ·Marian Ayensu ·Narendrasinh Parmar ·Rhythm Vasudeva ·Keyur Donda ·Harshit Doshi ·Fredrick Dapaah-Siakwan

Gastroschisis and omphalocele are the two most common congenital defects of the anterior abdominal wall.Exact etiologies remain unclear,but while gastroschisis is associated with young maternal age,maternal smoking,maternal alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy omphalocele is frequently associated with genetic disorders and other congenital anomalies [1].The incidence of gastroschisis in the United States (US) has increased with an estimated incidence of 4.6 per 10,000 live births (LB) between 2010 and 2014 [2].A recent study capturing information on 20% of infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the US showed a decrease in gastroschisis hospitalizations while that of omphalocele remained stable [3].However,it lacks generalizability [3].Our aim was to provide updated trends of gastroschisis and omphalocele hospitalizations in the US between 2010 and 2018 using population-based and nationally representative databases.

This study was a retrospective,repeated cross-sectional analysis using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) from 2010 to 2018.The NIS is published annually and includes approximately 7 million unweighted hospitalizations per year,which estimates approximately 35 million weighted national hospitalizations.The 2017 NIS sampling frame includes data from 48 statewide data organizations,covering over 97 percent of the US population [4].In contrast to the NIS,the KID is available every 3 years and includes pediatric discharges(age ≤ 20 years at admission) from community,non-rehabilitation hospitals in the US.The KID is sampled at 10% of uncomplicated in-hospital births and 80% of other pediatric cases [5].The 2016 KID sample has 47 participating member states,4200 hospitals with pediatric discharges,and almost 6 million weighted pediatric discharges.Because of its larger sample of pediatric patients,the KID was substituted for the NIS when available as in previous studies [6].

Neonatal hospitalizations ≤ 28 days of age at time of admission were identified using the“Neomat”variable.To prevent double-counting,hospitalizations transferred to other facilities were excluded.Hospitalizations with gastroschisis were identified using International Classification Code 9th edition (ICD-9) code 756.73 and ICD-10 code Q79.3.Since gastroschisis is managed with surgery,we performed a second analysis in which hospitalizations with gastroschisis were required to have both a diagnostic code and procedure code for gastroschisis repair.The hospitalization rate or the administrative prevalence of gastroschisis was calculated by dividing the number of hospitalizations for each year with the number of LB for that year and expressed as per 10,000 LB.The data on LB were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) [7].Furthermore,since gastroschisis and omphalocele are common abdominal wall defects,we repeated the analysis to trend the hospitalization rate of omphalocele in the US during the study period.We started the analysis from 2010 because the ICD-9 code for omphalocele (756.72) was introduced in 2009.The Healthcare Cost Utilization Project transitioned from ICD-9 to ICD-10 codes in the last quarter of 2015,and ICD-10 code Q79 was used from then on.Survey linear regression was used for trend analysis.Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.A two-sidedP

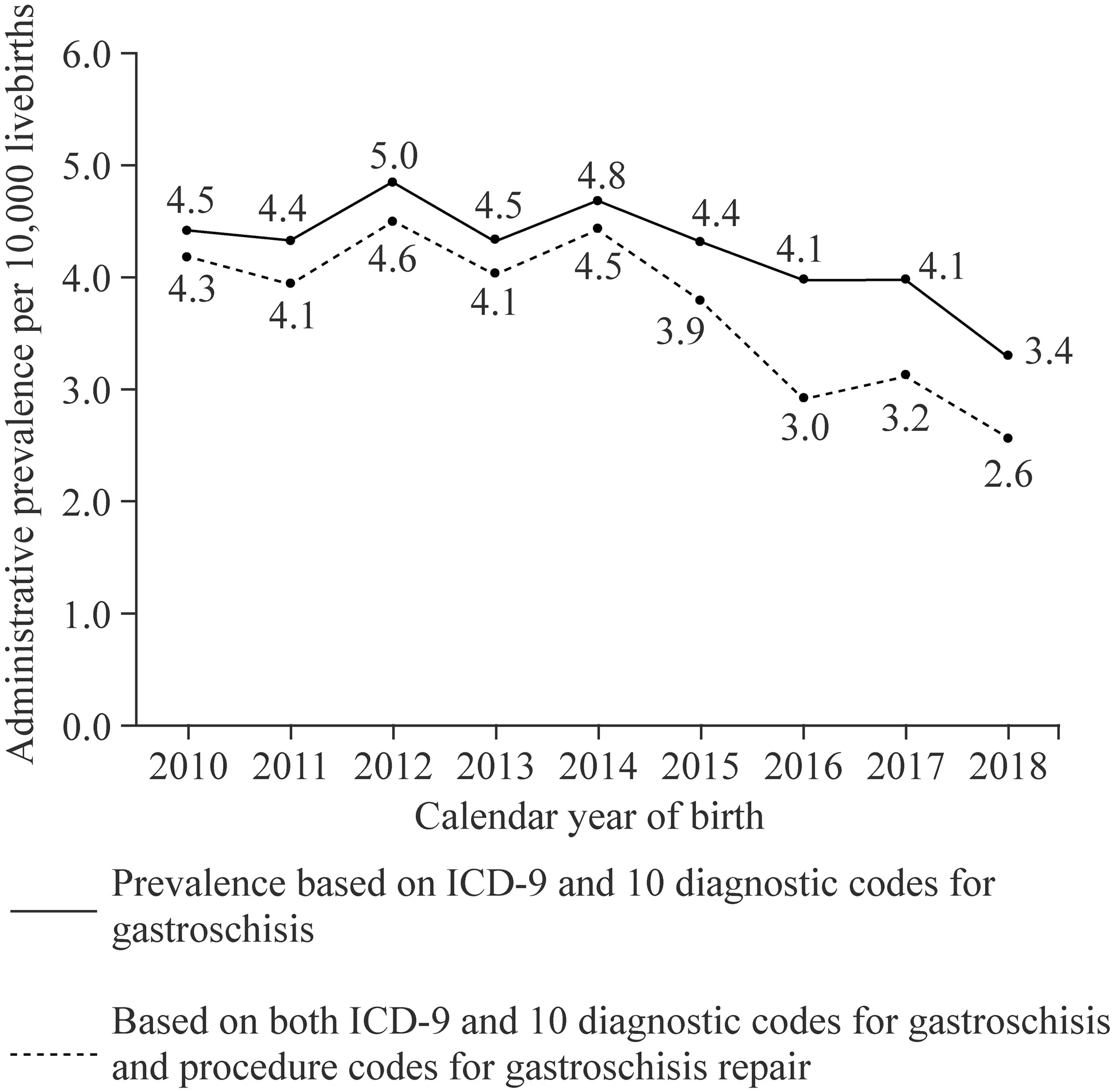

value < 0.05 was considered significant.During the study period,we identified 35.9 million LB and 15,427 newborn hospitalizations with a diagnostic code for gastroschisis.Gastroschisis prevalence was 4.3 per 10,000 LB,with significant decrease from 4.5 to 3.4 per 10,000 LB from 2010 to 2018 (P

=0.03).This remained unchanged when gastroschisis was identified with both ICD-9/10 diagnostic codes and ICD-9/10 procedure codes for gastroschisis repair (P

=0.019;Fig.1).Overall median length of stay (LOS) for gastroschisis was 34 days [interquartile range (IQR) 25—53] without significant change during the study period (34.3 to 34.0 days;P

=0.6).Overall mortality was 1.9% without significant change (1.8% in 2010 to 1% in 2018;P

=0.4).

Fig.1 Trends in the administrative prevalence of gastroschisis in the United States from 2010 through 2018.The prevalence declined when case ascertainment was defined by International Classification Code 9th edition (ICD-9) or 10 diagnostic codes alone or by both a diagnostic code and procedure code for gastroschisis repair

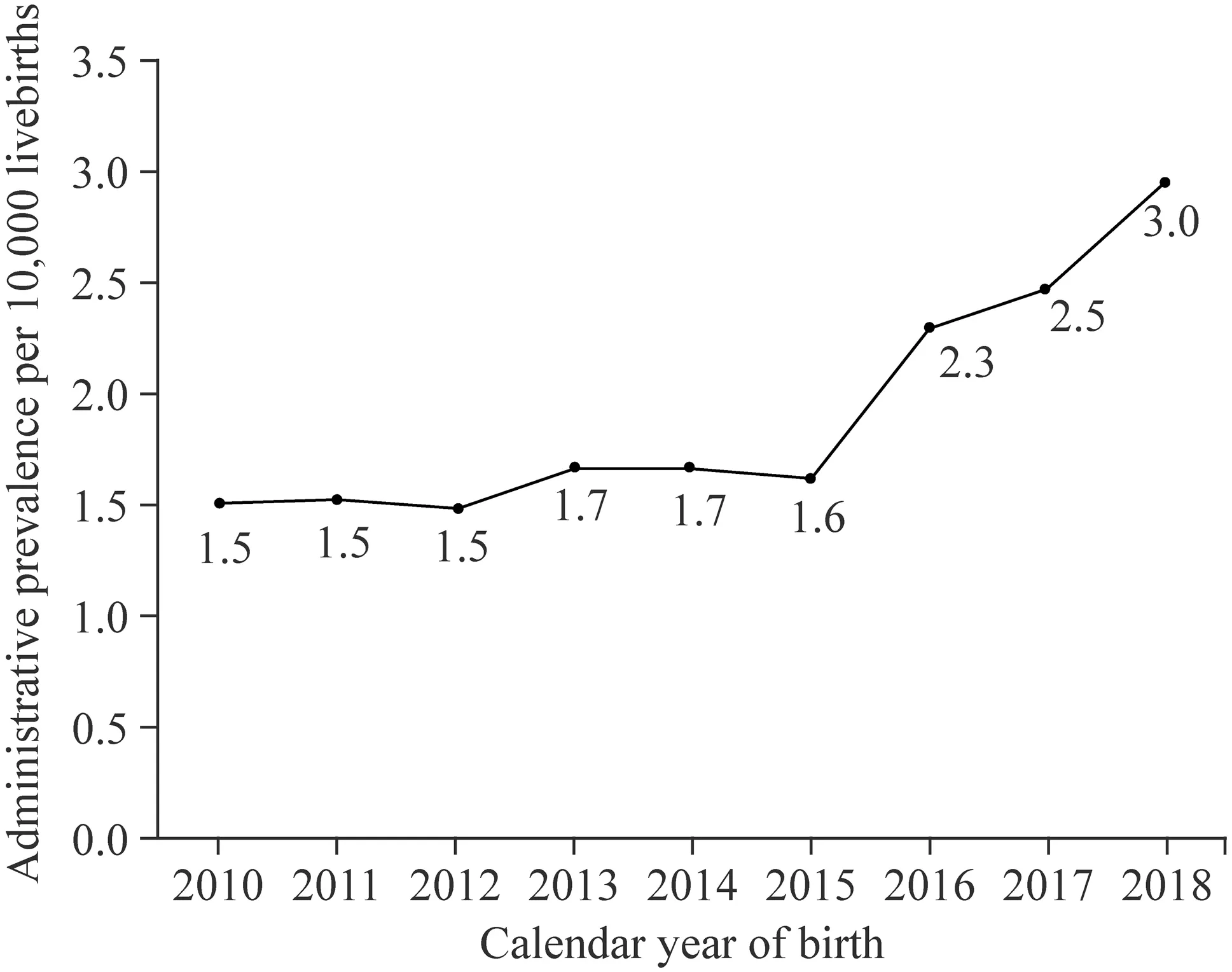

There were 6971 newborn hospitalizations with diagnostic code for omphalocele during the study period.This yielded an overall administrative prevalence of 1.9 per 10,000 LB.The prevalence of omphalocele remained stable from 2010 through 2015 (P

=0.12) but increased significantly from 1.6 to 3 per 10,000 LB between 2015 and 2018 (P

=0.003) (Fig.2).Among survivors to discharge,the median LOS was 12 days (IQR 4—35) without significant change during the study period (17.1 to 4.5 days;P

=0.06).The overall mortality was 21.9% with a statistically significant decline in mortality from 21.9% in 2010 to 17.3% in 2018 (P

< 0.001).

Fig.2 Trends in the administrative prevalence of omphalocele in the United States from 2010 through 2018.The prevalence remained stable from 2010 through 2015 but thereafter increased significantly

This population-based study provides updated trends in gastroschisis prevalence in the US from 2010 to 2018.We demonstrated a decreasing trend in prevalence of gastroschisis consistent with a recent multi-center report [3].The cause of gastroschisis is unknown,but young maternal age is the strongest and most consistent risk factor associated with gastroschisis [1].The proportion of women <20 years of age giving birth in the US has consistently declined since 2010 to record lows in 2019 which may contribute to the decreasing gastroschisis incidence [7].Maternal obesity has been linked to reduce the risk of gastroschisis [8].As per the CDC,pre-pregnancy obesity increased among women of all ages and was lowest for women under age 20 [9].This could possibly explain the decreasing prevalence of gastroschisis.The decline in prevalence of gastroschisis during the study period coincided with the transition from surgeons doing "bedside" procedures including reducing the herniated bowel and placing occlusive dressings over the defect [10].This is not a surgical procedure and may not be captured as“gastroschisis repair”or“surgical closure”of gastroschisis,giving the appearance of a prevalence decline.While a decreasing prevalence trend is welcoming news,further studies are needed to confirm and ascertain the drivers of this trend.

This study is one of the largest to track the prevalence of omphalocele over an extended period.The overall administrative prevalence of 1.9 per 10,000 LB accords with Stalling et al.who reported a prevalence of 2.1 per 10,000 LB from 2012 through 2016 [11].The present study demonstrates that the prevalence of omphalocele remained stable from 1.5 to 1.7 per 10,000 LB from 2010 to 2015.Several studies of birth defect registries from selected states in the US and Canada reported stable rates of omphalocele from 1995through 2007 [12,13].Using data from 351 NICUs from 34 states in the US from 2007 through 2015,Allman et al.found no significant change in the prevalence of omphalocele discharges [14].However,this study demonstrates that the omphalocele incidence increased from 1.6 to 3 per 10,000 LB from 2015 through 2018.The exact cause for omphalocele remains unknown.It may be caused by combination of genetic factors,maternal environmental exposure,alcohol and tobacco use or medicines used during pregnancy[15].However,alcohol use in pregnancy in the US is declining [7].Chromosomal abnormalities are associated with advancing age and since 2010,the number of babies born to mothers aged > 35 years has increased which may contribute to the observed trend in omphalocele prevalence [7,16].Additionally,2015 through 2018 coincides with the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 codes.This transition and possible diagnostic substitution could account for the observed increase in administrative prevalence of omphalocele.Another reason why omphalocele prevalence may be increasing is the coding of a hernia of the umbilical cord as an omphalocele.Such minor defects may have been coded as omphaloceles,when these are simply hernias of the cord.There is no accepted terminology that distinguishes a hernia of the cord from an omphalocele,but it may serve as another explanation as to why we noted a perceived increase in omphalocele prevalence.

It is reassuring that there was no significant change over time in LOS.The overall mortality of 21.9%,which is about twenty times that of gastroschisis,comports with those from previous studies.The high mortality is because,unlike gastroschisis,omphalocele is more likely to be associated with other major congenital defects and genetic disorders[1].Similar to a study from Finland,the downward trend in mortality from omphalocele is the result of advances in perinatal,neonatal,and pediatric surgical care [17].

The major strength of the study stems from use of two population-based databases covering the entire US population,making the findings nationally representative.Limitations of this study,as are most administrative database studies,are well represented.Large databases such as the NIS and KID are vulnerable to coding errors,omissions,and duplications.[18].However,the HCUP has established methods to ensure the validity of the data in the NIS [19].Furthermore,gastroschisis and omphalocele are considerable discharge diagnoses and more expected to be coded accurately since such coding is related to billing for inpatient hospital care.We analyzed prevalence for both gastroschisis and omphalocele rather than incidence rate because the NIS and KID include only live births.Further,pregnancies with fetuses complicated by either of these two anomalies may be terminated early in the pregnancy or may end in stillbirths which will not be captured by the HCUP databases[20].Thus,the administrative prevalence rates presented in this study likely underestimates the true incidence of both anomalies.The transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 could have affected the observed trends but this is unlikely since both ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic and procedure codes for gastroschisis have been validated [21,22].The National Birth Defect Prevention Network reported that the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10 did not significantly alter the incidence of gastroschisis or omphalocele [23].

This population-based analysis demonstrated that between 2010 and 2018,the hospitalization rate of gastroschisis decreased while that of omphalocele increased significantly after 2015.There are several possible reasons for these trends and further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,Rockville,MD and its partner organizations that provide data to the HCUP.Author contributions

All the listed authors substantially contributed to the conception and design,analysis and interpretation of data,and drafting of the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content,and final approval of the version to be published.Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public,commercial,or not-for-prof it sectors.Data availability

This study was an analysis of an existing nationwide database obtained upon request,which is available at The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) online website at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/.Declarations

Ethical approval

Our study included publicly available deidentified data and thus was exempt from review by the institutional review board.Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. World Journal of Pediatrics2022年7期

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年7期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Editors

- Information for Readers

- Prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in preterm,small for gestational age and low birth weight newborns:characteristics and cytokines profile

- Instructions for Authors

- Newborn emergency transport based on the fifth-generation wireless networks and blockchain

- X-linked osteogenesis imperfecta accompanied by patent ductus arteriosus:a case with a novel splice variant in PLS3