The Variability of Air-sea O2 Flux in CMIP6: Implications for Estimating Terrestrial and Oceanic Carbon Sinks※

Changyu LI , Jianping HUANG , Lei DING , Yu REN , Linli AN , Xiaoyue LIU , and Jiping HUANG

1College of Atmospheric Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China

2Collaborative Innovation Center for Western Ecological Safety, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China

3Enlightening Bioscience Research Center, Mississauga, L4X 2X7, Canada

ABSTRACT The measurement of atmospheric O2 concentrations and related oxygen budget have been used to estimate terrestrial and oceanic carbon uptake. However, a discrepancy remains in assessments of O2 exchange between ocean and atmosphere(i.e. air-sea O2 flux), which is one of the major contributors to uncertainties in the O2-based estimations of the carbon uptake. Here, we explore the variability of air-sea O2 flux with the use of outputs from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6 (CMIP6). The simulated air-sea O2 flux exhibits an obvious warming-induced upward trend (~1.49 Tmol yr-2)since the mid-1980s, accompanied by a strong decadal variability dominated by oceanic climate modes. We subsequently revise the O2-based carbon uptakes in response to this changing air-sea O2 flux. Our results show that, for the 1990-2000 period, the averaged net ocean and land sinks are 2.10±0.43 and 1.14±0.52 GtC yr-1 respectively, overall consistent with estimates derived by the Global Carbon Project (GCP). An enhanced carbon uptake is found in both land and ocean after year 2000, reflecting the modification of carbon cycle under human activities. Results derived from CMIP5 simulations also investigated in the study allow for comparisons from which we can see the vital importance of oxygen dataset on carbon uptake estimations.

Key words: air-sea O2 flux,carbon budget,land and ocean carbon sinks,CMIP6

1.Introduction

Human beings are now faced with continuous growth of the climate risk in the warming world. The climate change, occurring mainly as a consequence of anthropogenic CO2emissions, is already wielding its influences on ecosystems, economic sectors and people's health (Bopp et al.,2013; Huang et al., 2016; Frölicher et al., 2018; Wei et al.,2021). An increasing number of evidence warns us that actions should be taken urgently to minimize dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system, limiting global warming to 2 degrees - a threshold laid down by the Paris Agreement (Seneviratne et al., 2016; Huang et al.,2017b). Under this circumstance, the carbon neutrality,which refers to the balance of emissions of carbon dioxide with its removal, has become one of the most essential things human society needs to achieve in the mid-late 21st century (Dhanda and Hartman, 2011; Niu et al., 2021).

The land and ocean play an important role in the storage of atmospheric CO2(Dai et al., 2013; DeVries et al., 2019).It has been reported that the land and ocean have sequestered approximately half of the anthropogenic CO2emitted to the atmosphere in the past decades, which helps greatly buffer climate change (Friedlingstein et al., 2019;Gao et al., 2019, 2020). Thus, for a reasonable design of global warming mitigation and carbon neutrality strategies,there is a pressing need to address the effectiveness of terrestrial and oceanic carbon uptake and their susceptibility to climate change. According to this view, the measurement of atmospheric O2concentrations and related oxygen budget could provide us a concise and effective method to estimate carbon-uptake capacity of land and ocean on the basis of the close relationship between oxygen and carbon (Huang et al.,2018, 2021; Han et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021).

The accuracy of this O2-based carbon uptake estimation largely depends on how the oxygen data, especially the airsea O2exchange, is processed in the calculation. Early studies used to assume that there was no long-term oceanic effect of O2on the atmosphere (Keeling and Shertz, 1992; Battle et al., 2000). However, a number of indications have revealed the huge oceanic heat uptake under climate change(Willis et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2018; Cheng and Zhu,2018; Li et al., 2019), which implies the air-sea O2exchange could vary as a consequence of warming-induced solubility and circulation changes (Bopp et al., 2002; Li et al., 2020). Later studies have thus taken air-sea O2flux into consideration (Manning and Keeling, 2006; Tohjima et al.,2019), where the oceanic O2outgassing to the atmosphere is approximately estimated by a linear regression with ocean heat content, assuming the relationship between gas flux and heat flux bears a proportional relationship at the air-sea interface. In fact, mechanisms that control the variability of air-sea O2flux are rather complicated. Its temporal and spatial variations could be affected by changes in ocean primary production, ventilation and stratification, as well as oceanic internal modes such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation(ENSO) (Resplandy et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017). The intensified ocean heat uptake in the past few decades (Trenberth et al.,2014; Cheng et al., 2017) also wields its influences in the long-term period. How to accurately quantify the air-sea O2flux has therefore been one of the most important questions in the field of O2-based carbon uptake estimations.

Here, based on recent CMIP6 model simulations, we systematically investigate the characteristics of air-sea O2flux and from it, we subsequently calculate the terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks. We hope to provide a better understanding of air-sea O2flux under ongoing climate change. We also hope the applications of process-based air-sea O2flux from CMIP6 model simulations can provide a more comprehensive and reliable carbon sink estimation, compared with results from previous studies where the air-sea O2flux is not considered or simply approximated by a linear relationship between O2outgassing and heat content.

The paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 describes the detailed method of O2-based carbon sink estimations and the datasets, especially air-sea O2flux, used in this study. The climatology characteristics of air-sea O2flux and its variability under climate change in CMIP6 are shown in section 3.1. Section 3.2 provides our estimations of terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks with the use of this air-sea O2flux.Discussion and conclusion are presented in section 4.

2.Data and methods

2.1.O2-based estimations of terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks

2.1.1.Mass balanced equations for global oxygen and carbon budgets

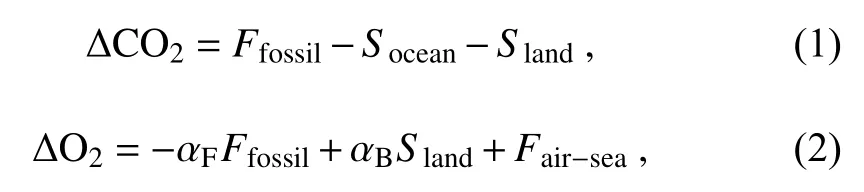

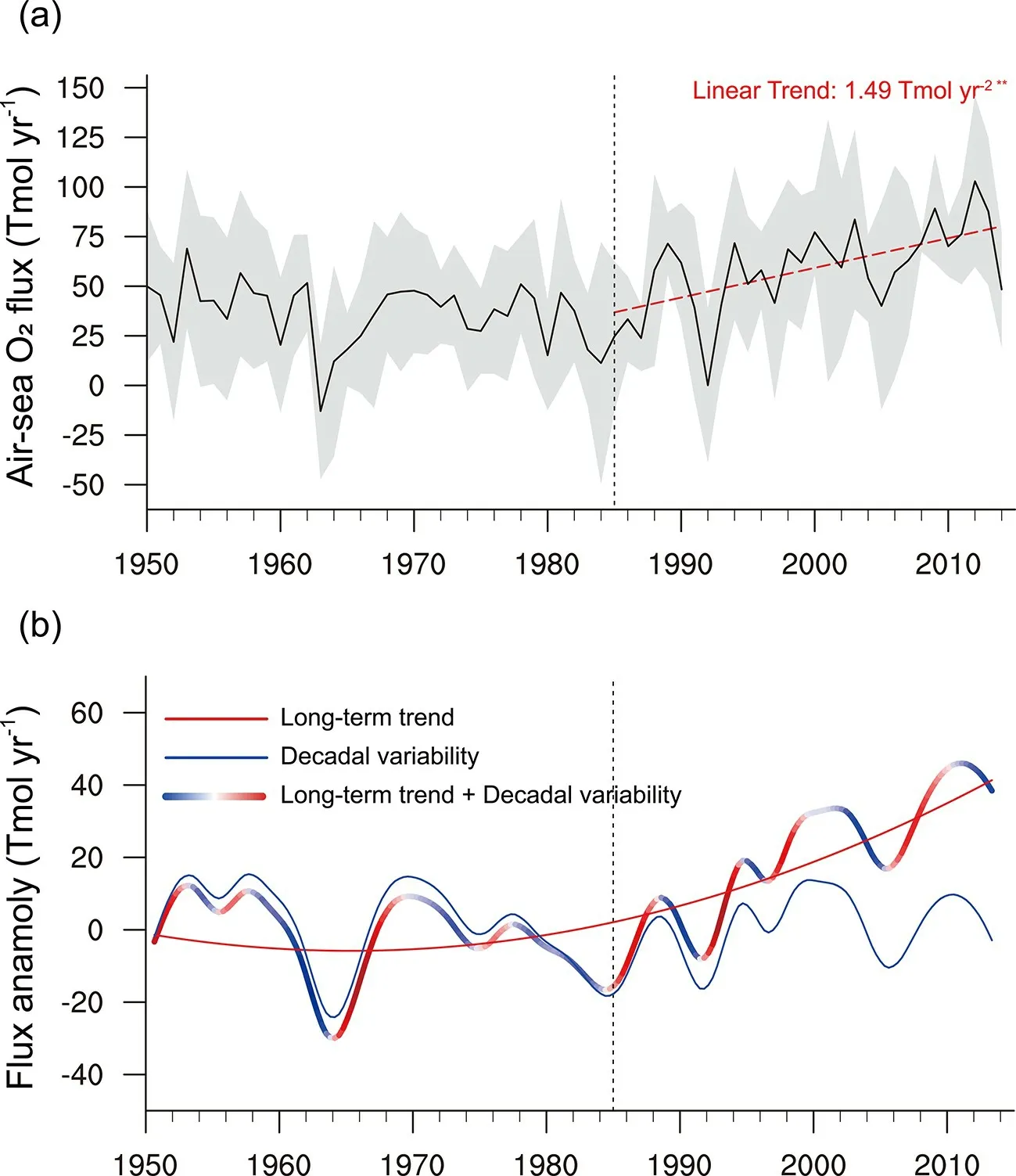

The assessments of land and ocean carbon sinks in this study are based on the strong relationship between oxygen and carbon, which can be written as follows (Keeling and Manning, 2014; Li et al., 2021):

where ΔCO2and ΔO2represent changes in atmospheric CO2and O2; Ffossilis the industrial CO2emissions, which mainly comes from fossil fuel combustion; Fair-searepresents the air-sea O2flux;αFandαBare dimensionless parameters which represent the globally averaged O2: CO2mole exchange ratios for fossil fuel burning and biological process; Slandand Soceanrepresent the net land carbon sink and ocean carbon sink, respectively. These two equations briefly describe the human impacts on the oxygen and carbon cycles. All variables in the equations mentioned above use the units of mole.

2.1.2.Observed atmospheric CO2and O2concentrations

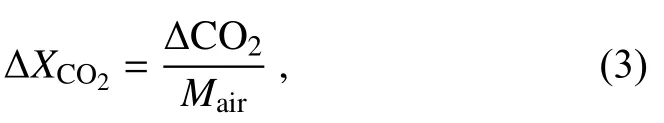

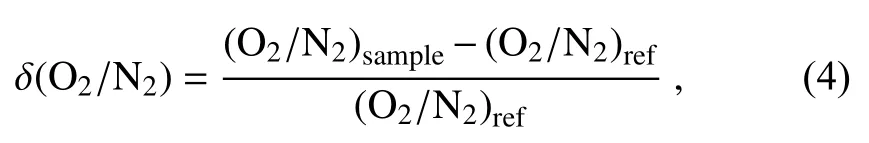

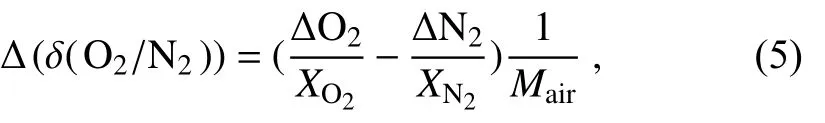

The concentrations of CO2in the atmosphere () are meas ured using the unit of “ppm” (parts per million). Its change can be expressed as

where Mairrepresents the global total number of moles of dry air (Mair=1.769×1020). The change of atmospheric O2concentrations, however, is typically measured as the mole ratio changes of O2/N2rather than the mole fraction such as ppm, due to its high abundance in the atmosphere. Following Keeling and Shertz (1992), the O2content of an air sample can be defined as

where (O2/N2)sampleis the mole ratio of O2to N2in the sample air and (O2/N2)refis the ratio in an arbitrary reference gas.Note thatδ(O2/N2) is typically multiplied by 106and expressed as “per meg” unit. The observed changes ofδ(O2/N2) in the atmosphere could thus be written as

where ΔO2and ΔN2are changes in moles of atmospheric O2and N2;andare the standard mole fraction of O2and N2in the atmosphere (= 0.2094 and= 0.7808).

According to Eqs. (1)-(5), the land and ocean carbon sink can be written as

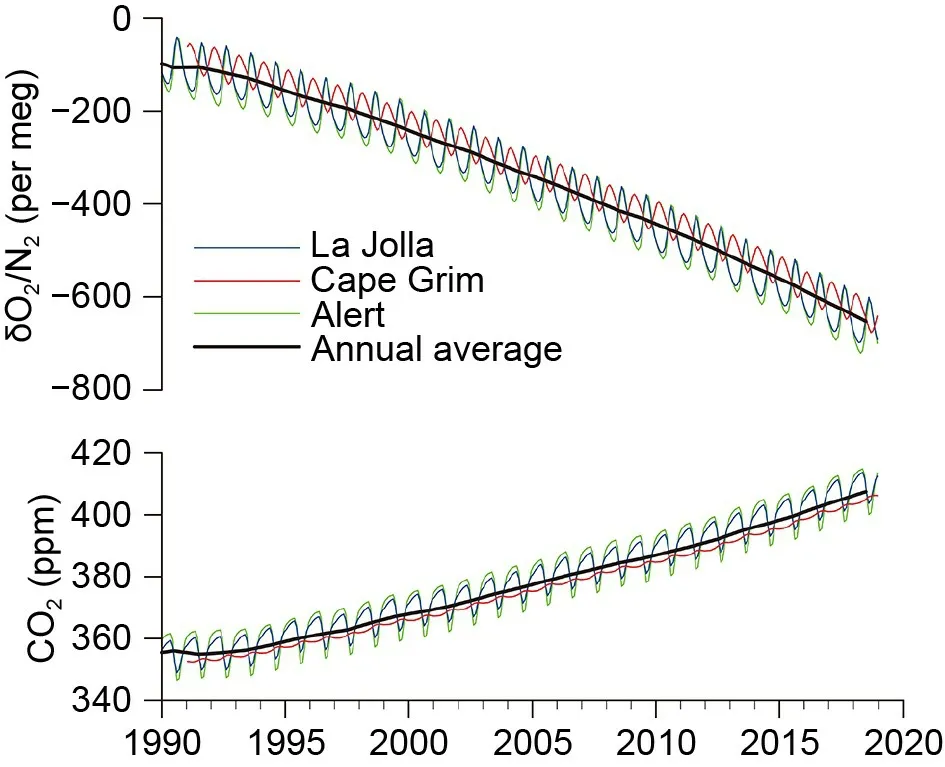

The observed timeseries of atmospheric CO2and O2concentrations [i.e.andδ(O2/N2)] can be downloaded from Scripps O2Program (https://scrippso2.ucsd.edu/),which provides records of both CO2and O2concentrations at 12 stations. In this study, we choose the longest three timeseries, at Alert (82.5°N, 62.3°W), La Jolla (32.9°N, 277.3°W), and Cape Grim (40.7°S, 144.7°E), respectively, and calculate the average with weights of 0.25, 0.25, 0.5 (given the equal weight in both hemispheres).

2.1.3.Global fossil-fuel combustion and the oxidative ratio

The global CO2emissions (Ffossil) are derived from Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC, Andres et al., 2016), which counts the consumptions of each type of fossil fuel. It should be noted that each fuel type has its own combustion ratio (αF), as shown in Table 1 (Liu et al., 2020).The global averaged αFtherefore slightly varies with time due to changes of global energy sources [Fig. S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material, (ESM)]. The oxidative ratioαBalso exhibits temporal variations due to modifications to global vegetation cover by human activities, however, it is generally believed the decrease of αBis less than 0.01 over 100 years (Randerson et al., 2006). We thus set the typical value ofαBas 1.10 according to previous studies (Keeling and Manning, 2014; Battle et al., 2019).

2.2.The air-sea O2 flux

Due to the importance of O2flux (Fair-sea) in estimating the carbon uptake, here we discuss it in greater detail. The air-sea O2flux evaluated in this study builds on the processbased ocean physical and biochemical models developed as part of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6(CMIP6), which can be downloaded from https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The detailed descriptions of these models are presented in Table 2. Here we choose the historical experiments of these models to match the timeseries of O2observations. Note that the air-sea O2flux is calculated by the model in mol m-2s-1, so we convert to mol of oxygen per year (mol m-2yr-1). For sake of comparisons and analysis, all the model results are gridded to 1°×1° resolution.

Furthermore, it should be noted that, due to import of N2in the atmospheric O2observations, oceanic N2outgassing must be considered in the calculations. The total effect of the ocean on carbon sinks could thus be expressed as Eq.(8). Here we apply the tuning parameterβ=0.88 to represent the negative effect of N2outgassing (Keeling and Manning,2014); it can be shown that the equation can be written as

The related ocean physics variables such as sea temperature, salinity, and mixed layer depth in CMIP6 are also used in this study to analyze mechanisms of O2flux change.

2.3.The EEMD method

We use the ensemble empirical mode decomposition(EEMD) method to separate the human-induced long-term signals from natural decadal variability in the time series of airsea O2flux. This noise-assisted method can separates scales naturally without any prior subjective criterion (Ji et al.,2014; Huang et al., 2017a). EEMD performs operations that partition a series into different “modes” (Intrinsic Mode Functions, IMFs), which are expressed by the following equation:

Table 1. Typical oxidative ratio for each fuel type.

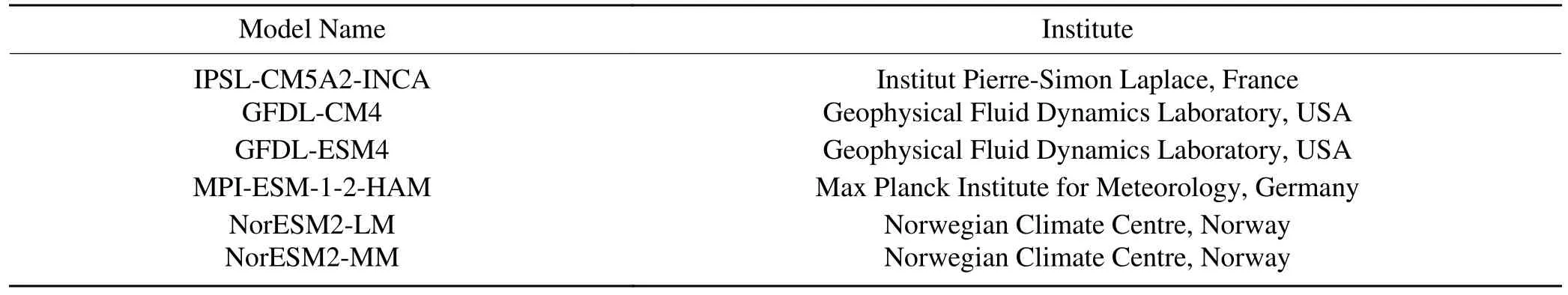

Table 2. The CMIP6 models used in this study to obtain the air-sea O2 fluxa.

where IMFi(t) is the ith IMF, and rn(t) is the residual of data X(t). The detailed descriptions of the steps on how to execute EEMD method can be found in Text S1 in the ESM. In this study, the noise added to the data has an amplitude that is 0.2 times the standard deviation of the raw data, and the ensemble number is 400. The number of IMFs is 6. A python version of EEMD is available at https://www.github.com/laszukdawid/PyEMD (Laszuk, 2017).

3.Results

3.1.The characteristics of air-sea O2 exchange in CMIP6

3.1.1.Climatological status of air-sea O2flux in 1985-2014 and evaluation against available studies

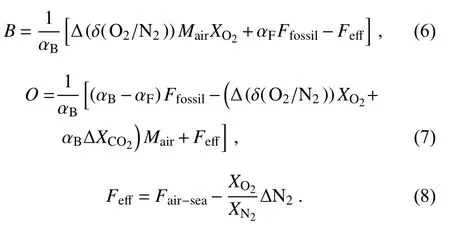

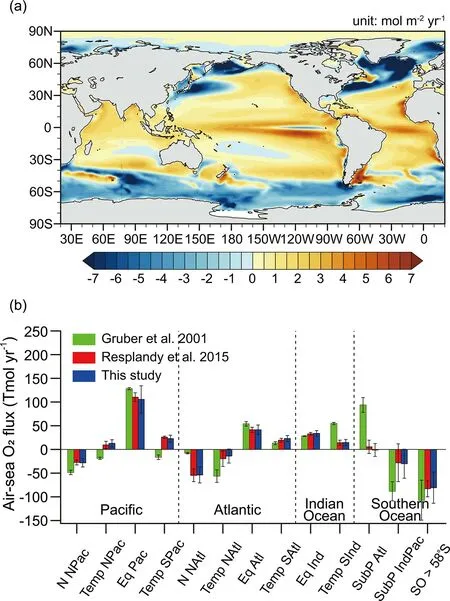

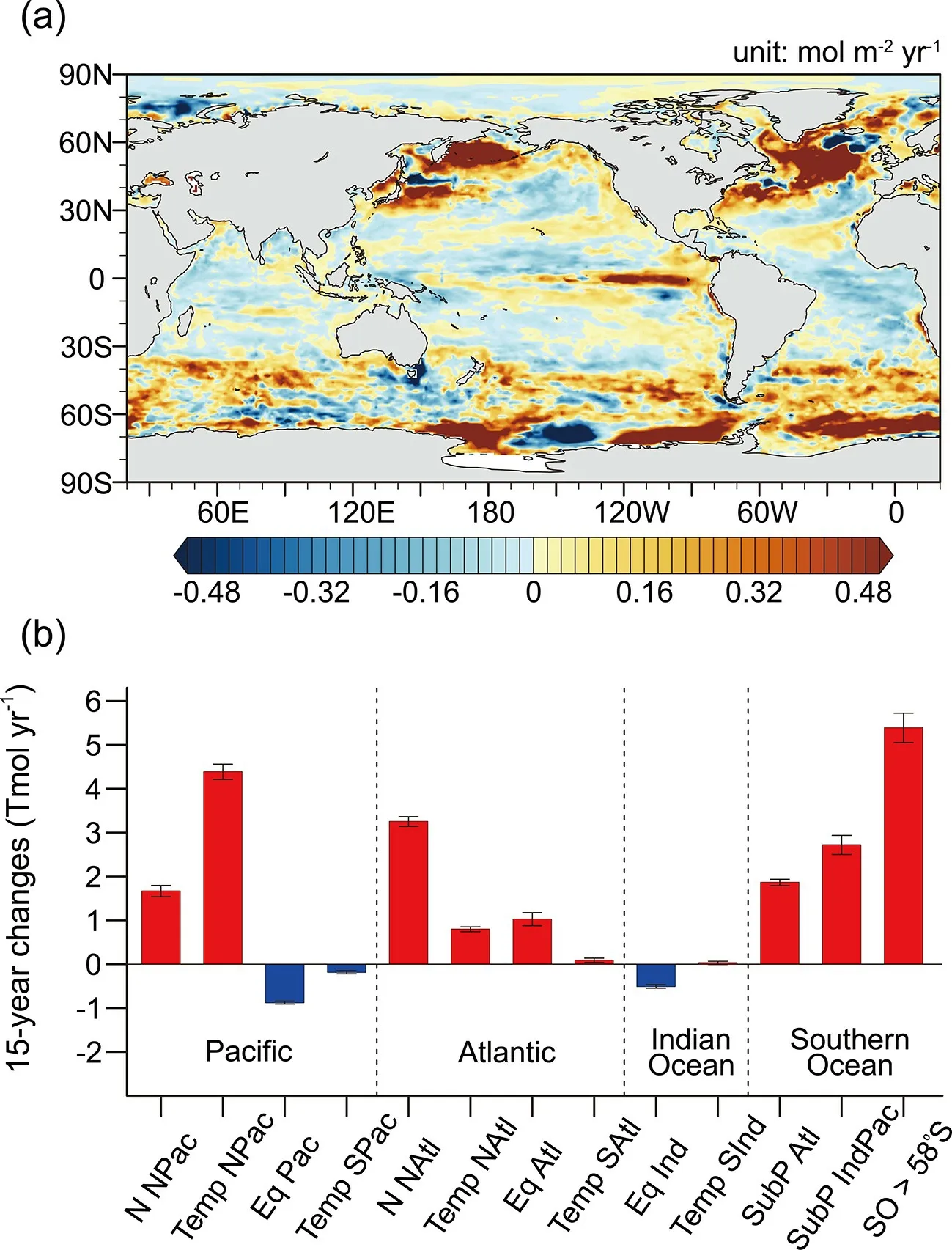

The transfer of gases across the air-sea interface is controlled by several physical, biological and chemical processes in the atmosphere and ocean, which could influence not only the partial pressure differences but also the efficiency of transfer processes (Wanninkhof, 1992; Liang et al., 2013).The air-sea O2flux thus varies considerably among the ocean regions. Figure 1a presents the model-ensemble-mean of annual air-sea O2flux averaged from 1985 to 2014 in CMIP6 historical experiments (positive means a flux to the atmosphere). Spatial distributions of O2flux in each individual model can be found in Fig. S2 in the ESM. The results show an overall net O2outgassing from ocean to the atmosphere at low latitudes, while a significant influx of O2occurs at high latitudes. The tropical and subtropical ocean(30°S-30°N) emits approximately 250.8±38.4 Tmol O2per year (1 Tmol = 1012mol), which is partly compensated by O2absorption in the high-latitude ocean, about -105.2±24.8 and -87.2±41.4 Tmol yr-1in the Northern (>30°N) and Southern Hemisphere (>30°S), respectively, eventually leading to a net O2outgassing of ~58.5±9.6 Tmol yr-1over the global ocean. This pattern highlights the solubility effect driven by meridional temperature gradients, as well as combinations of the dynamical and biological effects, which lead to a surplus of oceanic O2production in low latitudes (Bopp et al.,2002).

Furthermore, the simulated O2flux is evaluated against results derived from previous studies (Gruber et al., 2001;Resplandy et al., 2015), which are found in Fig. 1b . The ocean is divided into 13 regions for sake of comparison (Fig.S3 in the ESM). The patterns presented by the ensemblemean of the suite of models in CMIP6 correspond well with estimations based on ocean inversions (Gruber et al., 2001),except for the Sothern Ocean. The results derived from Gruber et al. (2001) exhibit a much stronger O2outgassing in the subpolar South Atlantic [95.0 Tmol yr-1differences between this study and Gruber et al. (2001)]. However, this difference could roughly cancel out when we integrate the whole Southern Ocean regions, as it also exists a larger O2influx in subpolar Indian-Pacific Ocean and Oceans >58°S (differences of-58.1 and -26.2 Tmol yr-1, respectively). Besides, the spatial distribution shows a remarkable consistency with preindustrial experiments presented by Resplandy et al. (2015), indicating the robust of models in simulating O2flux.

3.1.2.Modifications of air-sea O2flux under global warming

Temporal evolution of the air-sea O2flux reveals that significant modifications have been occurring in response to ongoing climate change (Fig. 2). In Fig. 2a, we can see sizable oscillations of air-sea O2flux during the period 1950-85.Also obvious is the increase of oceanic O2outgassing found since the mid-1980s, with an upward trend of ~1.49 Tmol yr-2(significant at 0.01 level). Based on EEMD method,here we split the evolution of air-sea O2flux into decadal variability (i.e. sum of IMFs 2-5 from EEMD) and the longterm trend (i.e. IMF 6). As shown in Fig. 2b, the time series of air-sea O2flux from 1950 to 1985 is primarily dominated by natural decadal variability, while the human-induced long-term changes gradually wields its influence after 1985.The combination of the two terms eventually lead to an overall upward trend since the 1980s, with natural variability modulating the long-term trend.

The EOF analysis was applied to the de-trended global air-sea O2flux over the 1985-2014 period to explore the spatio-temporal distributions of decadal variability (Fig. 3).The first two modes explain approximately 58% of the total variance. The highest decadal variability of O2flux is found in the North Pacific, the North Atlantic and the Southern Ocean (Figs. 3a, 3b). The most significant changes in the Atlantic are mainly in the high-latitude areas where the sinking branch of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation(AMOC) is located, the changes of which could significantly influence climate (Yang et al., 2016; Wen et al., 2018; Yang and Wen, 2020). In the Southern Ocean, the spatial pattern exhibits opposite phase between 40°S and 65°S, suggesting the potential relationship with the Southern Annular Mode(SAM). Time series associated with EOF modes reveal a cycle of ~15 years with different phases in PC1 and PC2(Fig. 3c). The standard deviation of the decadal variability derived from EEMD also shows a similar spatial distribution compared with the EOF analysis (Fig. S4 in the ESM).

The long-term changes of air-sea O2flux, which are generally considered as modifications to anthropogenic forcing,is presented in Fig. 4. Positive values are mainly found in the high latitude areas (Fig. 4a), where strong O2uptake in the climatological state is seen (Fig. 1a), revealing the weakening of the oceanic O2absorption capacity from the atmosphere. The maximum increase of the flux occurs in the Southern Ocean (SO>58°S), where it reaches 5.39±0.34 Tmol yr-1. The next two highest increases occur in the North Pacific (Temp NPac) and North Atlantic (N NAtl), with an increase about 4.39±0.17 and 3.25±0.11 Tmol yr-1, respectively (Fig. 4b). This long-term change could be attributed to human-induced solubility and circulation changes. The solubility of dissolved O2has been decreasing in the warming ocean. This effect could be written as:

Fig. 1 The spatial distributions of annual mean air-sea O2 flux (a) averaged from 1985 to 2014 in CMIP6 historical simulations, and (b) compared with two other studies. Positive flux in Fig. 1a means O2 outgassing from ocean to the atmosphere.For sake of comparisons, the ocean is partitioned into 13 regions as shown in Fig. S3 in the ESM. The results from Li et al (2020) are similar with Resplandy et al 2015,which are not shown here.

where Q is the total sea-surface downward heat flux; Cprepresents the heat capacity of sea water; ∂O2/∂T is the temperature dependence of O2solubility which could be derived from Garcia and Gordon (1992). Our calculations reveal that roughly one quarter of the increase is directly associated with reduced solubility in the warming ocean, which is consistent with results found by Li et al. (2020) and Plattner et al. (2002). Warming-induced ocean stratification also plays an important role in the modifications of air-sea O2flux. Strong shoaling of the mixed layer is found in the North Atlantic and widespread areas in the Southern Ocean(Fig. S5 in the ESM), which prevents oxygen supplies from reaching the deeper layers and eventually result in a positive contribution to the air-sea O2flux.

3.1.3.Comparisons with CMIP5: What’s new about the air-sea O2flux we can learn in CMIP6

In Li et al. (2020), the air-sea O2flux derived from CMIP5 is applied to investigate the terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks. It is therefore necessary to clarify the difference of the flux between the CMIP5 and CMIP6 as well as its influences on carbon sink estimations.

Fig. 2 Time series in the historical period (1950-2014) of (a) air-sea O2 flux and (b)its EEMD decomposition. The red dashed line in (a) represents linear regression from 1980 to 2014, significant at the 0.01 level. Shaded area is the uncertainty of the flux represented by the standard deviation of these models. The decadal variability in (b)(the blue solid line) is the sum of IMF2-5 from the EEMD and the long-term trend(the red solid line) is the IMF6. Positive values in both panels indicate oceanic O2 outgassing to the atmosphere.

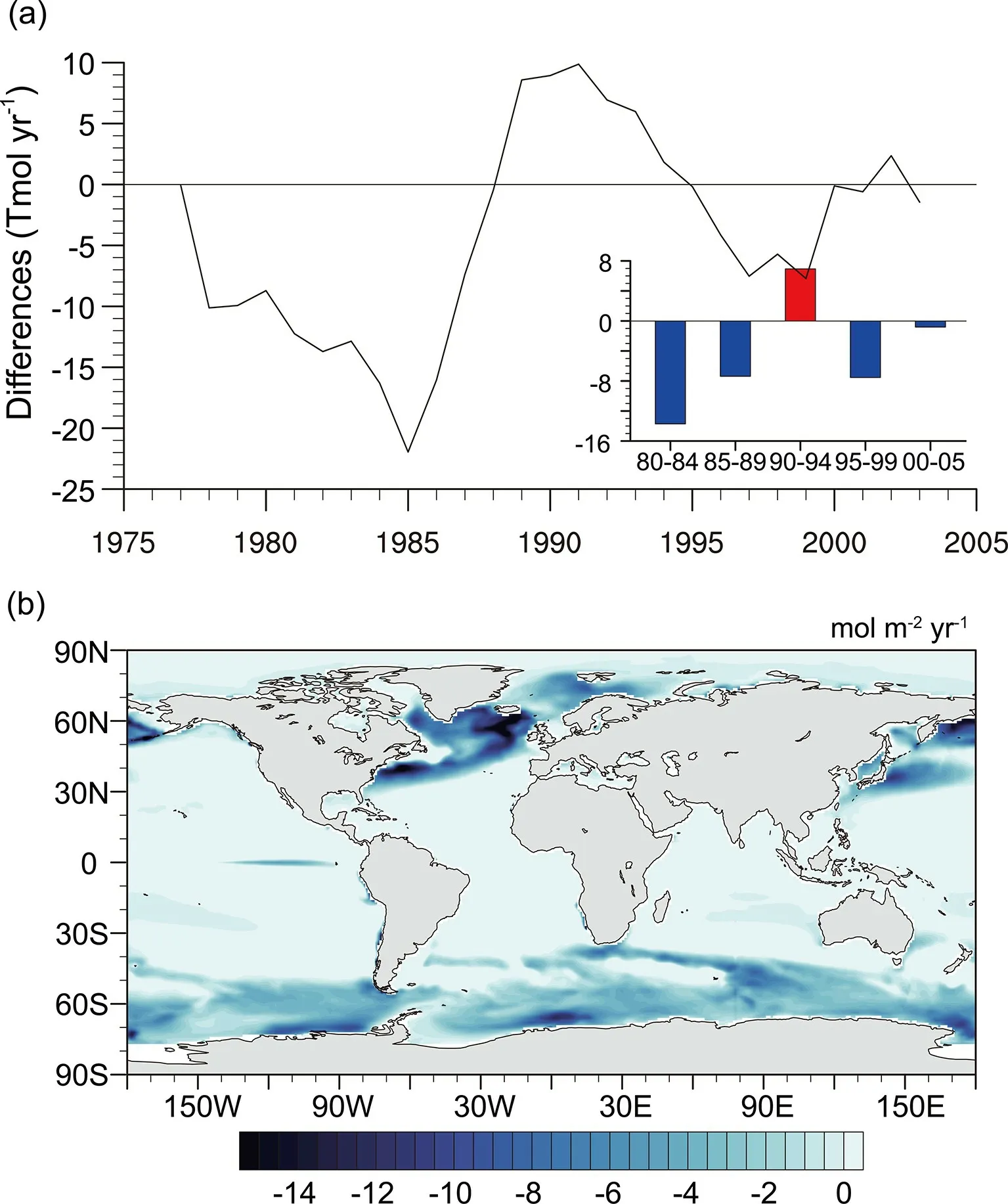

For a simulated historical period from 1975 to 2005,the comparisons between CMIP6 (this study) and CMIP5[derived from Li et al. (2021)] reveal pronounced temporally varying differences of air-sea O2flux (Fig. 5). Except for a short period of time around year 1990, the ocean in CMIP6 exhibits an overall smaller oceanic O2outgassing, up to -22 Tmol yr-1, than in CMIP5. Spatial patterns shown in Fig. 5b reveal that this difference is mainly caused by the intensified high-latitude oceanic O2uptake in CMIP6, especially in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean. Although there still exists relatively large uncertainties, this intensified uptake in CMIP6 is more consistent with the regional observations in the Southern Ocean (Bushinsky et al., 2017), reflecting the improvement of simulations in CMIP6. Furthermore,slight difference also exists in the long-term trend of air-sea O2flux. An upward linear trend of ~1.52 Tmol yr-2has been found in CMIP6 during the period 1985 to 2005, while the trend is approximately 1.12 Tmol yr-2in CMIP5. This indicates an accelerated oceanic O2outgassing in CMIP6,which is tightly associated with ocean deoxygenation (Bopp et al., 2013; Palter and Trossman, 2018; Li et al., 2020).

According to Eqs. (6)-(8), this difference in O2flux could lead to a total fluctuation as large as 0.4 GtC yr-1in the estimated carbon sink. It should be noted that, besides the air-sea O2flux, the estimated carbon sink could also be influenced by the choice of other oxygen datasets in the study, which is therefore rather complicated. Comparisons of O2-based carbon sinks between this study and Li et al.(2021), as well as other previous studies, will be discussed in detail in the following section.

3.2.Estimates of terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks

3.2.1.O2-CO2diagram from 1990 to 2014

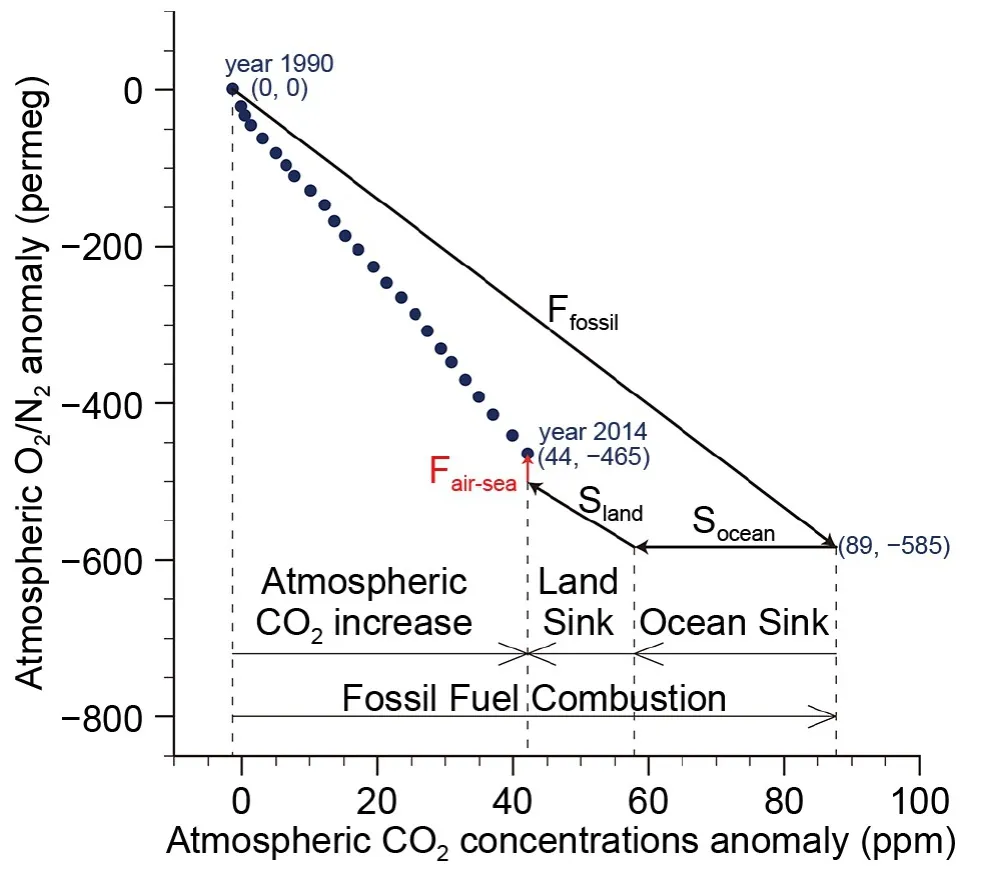

Simulations of the air-sea O2flux in CMIP6 provide a valuable complement for the O2-based carbon uptake estimations. With the use of air-sea O2flux as well as other O2-related variables, the global terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks could be calculated based on Eqs. (1)-(9). The processes are briefly diagrammed in Fig. 6.

Fig. 3 EOF analysis of de-trended global air-sea O2 flux over the 1985-2014 period.The spatial patterns of the first and second EOF mode are presented in panel (a) and(b), respectively. The black and blue lines in (a) represent the temporal coefficient of the two modes. Note that the original timeseries is pre-processed with a pentad running average to remove the influence of the high-frequency oscillations.

The dots in Fig. 6 are the observed anomalies of global atmospheric CO2(horizontal axis) and O2/N2concentrations(vertical axis) from 1990 to 2014. Here we set the concentrations in year 1990 as the base point (0 ppm, 0 per meg).These dots show an increase of CO2concentration and a simultaneous decline in O2/N2concentration with time. For example, the concentrations in 2014 could be written as (44 ppm, -465 per meg) in this coordinate system, which means a 44 ppm increase of CO2concentration and a 465 per meg decrease of O2/N2concentration in the atmosphere since year 1990. The arrows in Fig. 6 reveal the effect of related processes on atmospheric CO2and O2/N2concentration changes. For example, the fossil fuel combustion is marked by the black arrow in Fig. 6, starting at (0, 0) and ending at(89.0, -584.7), meaning that the fossil fuel burning would have contributed to a total 89.0 ppm increase of CO2(that is,a release of 189.0 GtC CO2, 1 Gt = 1015g, 1 ppm = 2.12 GtC)and 584.7 per meg decrease of O2/N2concentration during 1990-2014, if no other processes were involved. This is to say, the observed decline of O2/N2(~465.1 per meg) is a bit smaller compared with the decline directly derived from fossil fuel combustion (584.7 per meg) during 1990-2014.More importantly, the observed atmospheric CO2concentration only increases by about half of the value derived from fossil fuel combustion (that is, ~44 ppm, as shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7), from which we can thus infer huge land and ocean carbon sinks, absorbing a total of 96.6 GtC carbon.The projections of these arrows on the x- axis are also drawn in Fig. 6, which reflect how the atmospheric CO2concentrations are influenced by the related processes. The land and ocean carbon sinks can be separated from the total carbon uptake according to Eq. (6) and Eq. (7), as 33.5 GtC and 63.2 GtC, respectively, during this period.

Fig. 4 15-year changes in the long-term trend of air-sea O2 flux since 1985. The error bars in panel (b) represent the uncertainty of flux change.

It should be especially noted that the air-sea O2flux plays an important role in the carbon uptake estimations.The ocean emits ~1.54 Pmol O2(1 Pmol = 1015mol) to the atmosphere (sum of the air-sea O2flux from 1990 to 2014 in Fig. 2a), making a positive contribution of about 36.7 per meg to the atmospheric O2/N2concentration (red vector in Fig. 6). Despite this air-sea O2flux being relatively small, it plays an important role in the estimation of land and ocean carbon sinks. Figure 8 describes the situation assuming that the air-sea O2flux is negligible on a multiannual-to-decadal timescale, as proposed in the early studies (Bender and Battle, 1999; Battle et al., 2000). If the air-sea O2flux is not considered in the O2budget, the ocean carbon sink would be apparently underestimated by approximately 14.8 GtC during 1990-2014, while the land carbon uptake would be largely overestimated (bar charts in the top right of Fig. 8).

3.2.2.Averaged terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks in different periods

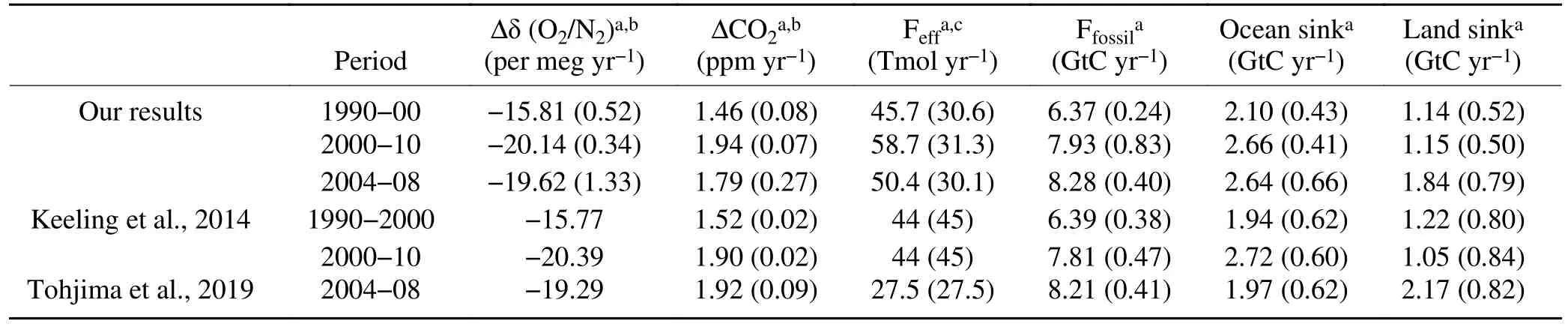

We subsequently calculated the averaged terrestrial and oceanic carbon uptake over several different periods and compared them with previous O2-based carbon uptake estimations(Table 3). Here, we use the linear trend of atmospheric O2/N2and CO2concentrations in the period to represent the O2/N2and CO2changes in Eqs. (6)-(7) (Δδ(O2/N2) and ΔCO2).For observed atmospheric concentration changes and fossil fuel consumption (Ffossil), our results are relatively consistent with Keeling et al. (2014) (differences less than 0.06 ppm yr-1in ΔCO2and 0.12 GtC yr-1in Ffossil). The effect of airsea flux in our study (which are derived from process-based CMIP6 model simulations, as described above) shows a relatively large discrepancy with that in Keeling et al. (2014)(which is calculated based on the linear regression between O2flux and net changes of ocean heat content). Our results show an averaged ocean and land carbon sink of 2.10±0.43 and 1.14±0.52 GtC yr-1, respectively, during 1990-2000.An increase is found in both ocean and land carbon sinks during 2000-10, while results from Keeling et al. (2014) show an increase in ocean sink but a decline in land sink. Furthermore, the averaged carbon sinks from 2004 to 2008 in our study (2.64±0.66 GtC yr-1for ocean and 1.84±0.79 GtC yr-1for land) are generally larger than that in Tohjima et al.(2019) (1.97±0.62 GtC yr-1for ocean and 2.17±0.82 GtC yr-1for land), which could also be partly attributed to the discrepancy in the air-sea flux (Table 3).

Fig. 5 Differences of air-sea O2 flux between CMIP6 and CMIP5 during period 1975-2005 (i.e.FLUXCMIP6 minus FLUXCMIP5). The black line in (a) is the time series of the difference and (b)shows the spatial distribution of the difference averaged from 1975-2005.

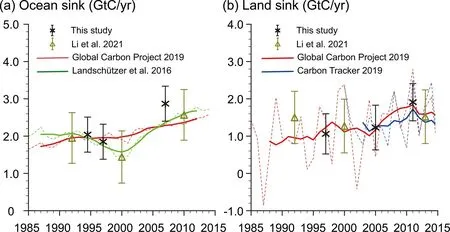

To further explore the temporal changes of ocean and land carbon sinks over the past two decades, the averaged ocean and land carbon sinks were calculated for several representative periods: 1991-97, 1994-2000 and 2004-10 were selected for the estimates of averaged ocean sinks; meanwhile, 1994-2000, 2002-08 and 2008-14 were selected for the estimates of averaged land sinks. These results are shown as the asterisks in Fig. 9, accompanied by time-continuous estimations from the Global Carbon Project (GCP,Friedlingstein et al., 2019), Landschützer et al 2016 and Carbon Tracker (CT, Jacobson et al., 2020). The estimates by GCP clearly show a quasi-monotonous increase of the oceanic carbon sink over the past few decades (Fig. 9a, red line). However, the oceanic uptake in our results show a decline from 2.04±0.47 GtC yr-1in 1991-97 to 1.85±0.45 GtC yr-1in 1994-2000. A significant upward trend is subsequently found in the 21st century, with ocean uptake increasing to 2.87±0.47 GtC yr-1in 2004-10. This temporal pattern is generally consistent with results derived from observed surface partial pressure of CO2in Landschützer et al. (2016)(Fig. 9a, green line), which may occur as consequences of the combined influence of anthropogenic forcing and oceanic internal modes. The net terrestrial carbon uptake estimated in this study corresponds well with the results derived from GCP. An increase of land carbon uptake (from 1.23±0.60 GtC yr-1to 1.91±0.50 GtC yr-1according to our estimations) could be found in the 2000s (Fig. 9b) which has been reported by several atmospheric inversion and model-based studies (Keenan et al., 2016; Ballantyne et al.,2017; Piao et al., 2018). Despite the fact that the mechanisms behind this increase are still under discussion, it is generally believed that the changes in land use, modifications of terrestrial productivity and respiration, as well as climatic variations of temperature and moisture are responsible for changes in terrestrial carbon uptake (Chen et al., 2020; Piao et al., 2020a, b; Yue et al., 2020).

Fig. 6 Changes in observed atmospheric concentrations of O2/N2 and CO2 from 1990 to 2014. The blue dots represent the annual averaged O2 and CO2 anomaly (here we choose the concentrations in 1990 as the reference value). The vectors in the diagram schematically illustrate the contribution of each process related to the changes in O2 (vertical axis) and CO2(horizontal axis) during this period. The effect of air-sea O2 flux is highlighted in red.

Fig. 7 The observed time series of atmospheric O2/N2 and CO2 concentrations. The blue, green and red lines represents observations in La Jolla (32.9°N, 277.3°W), Alert (82.5°N,62.3°W), and Cape Grim (40.7°S, 144.7°E), respectively. The black line is the annual mean concentrations averaged among the three stations with a weight of 0.25, 0.25 and 0.5.

Fig. 8 Role of air-sea O2 flux in O2-based carbon sinks estimations. The diagram is same as Fig. 6, except for no airsea O2 flux considered in the calculation. The bar charts in the top right show the comparisons between estimated ocean/land carbon sink with and without O2 flux correction.

3.2.3.Influence of oxygen datasets on estimated carbon uptake

In this section, we specifically investigate the differences of the carbon sinks from that in Li et al. (2021). As mentioned in section 3.1.3, the air-sea O2flux used in Li et al. (2021) is derived from CMIP5, while CMIP6 simulation of the flux is used in this study. Meanwhile, the other O2-related variables(such as atmospheric O2decline) in Li et al. (2021) are derived from the oxygen budget proposed by Huang et al.(2018), which is also different from this study. Terrestrial and oceanic carbon uptakes estimated by Li et al. (2021) are depicted by the triangles in Fig. 9. From the comparisons between this study and Li et al. (2021), we can discern the role of oxygen data in carbon sink estimations.

For the terrestrial carbon sink, both of the two studies corresponds well with GCP in the 21st century, which exhibit an enhanced uptake mentioned in section 3.2.2. However,the result from Li et al. (2021) seems to present an unrealistically high land carbon uptake (1.50 GtC yr-1) in the 1990s,while the current study behaves in good agreement with GCP during this period (1.06 GtC yr-1). The oceanic carbon uptake in both this study and Li et al. (2021) exhibits a similar variability with that in Landschützer et al. (2016) (that is, adownward trend in the 1990s subsequently followed by an upward trend in the 2000s). Despite this, discrepancy occurs around year 2010, as shown in Fig. 9a. The estimated oceanic carbon uptake in this study (2.87 GtC yr-1) is relatively larger than it in Li et al. (2021) (2.45 GtC yr-1) and GCP (2.36 GtC yr-1).

Table 3. Estimations of O2-based carbon sinks in different periods.

Fig. 9 Estimated ocean and land carbon sinks in different studies. The asterisks and triangles are seven-year averaged carbon sinks in this study and Li et al 2021, with error bars representing uncertainties of the estimations.The time series of carbon sinks derived from Global Carbon Project 2019, Landschützer et al 2016 and Carbon Tracker 2019 are colored in red, green and blue, respectively. The thin dashed lines and the thick solid lines are annual and seven-year running averaged carbon sinks, respectively.

Overall, both of the two studies reveal an enhanced carbon uptake in the 21st century. This study provides a more reliable estimate of the terrestrial carbon uptake in the 1990s, while the oceanic carbon sink in Li et al. (2021) is more consistent with the Global Carbon Project after year 2010. Our calculations show that the differences in air-sea O2flux (Fair-sea) and atmospheric O2change (Δ O2) are the main contributors to the discrepancies. If the difference in O2flux is expressed as ΔFair-sea(the other variables remain unchanged), its influence on the terrestrial and oceanic carbon uptake could then be respectively expressed as ΔB=-β/αBΔFair-seaand ΔO=β/αBΔFair-sea,according to Equations 6-8. This implies that a weakened oceanic O2outgassing, approximately -22 Tmol O2yr-1, would lead to an increase of 0.21 GtC yr-1land carbon sink and a simultaneous opposite effect on ocean carbon sink. For the period 1990-95, Li et al. (2021) shows a smaller declining trend of atmospheric O2and oceanic outgassing in 1990-95, which could eventually lead to a larger land uptake in Li et al.(2021) during this period. These results highlight the vital importance of oxygen datasets on carbon sink estimations.

4.Summary and discussion

We use the coupled ocean biogeochemistry models in CMIP6 to investigate the modifications of air-sea O2flux under climate change and its influences on the estimations of global terrestrial and ocean carbon uptake. Our results show an enhanced global oceanic O2outgassing to the atmosphere since the 1980s, accompanied by a strong decadal variability dominated by oceanic internal modes. Consistent with Li et al. (2020), this study shows maximum changes of flux mainly occurring in the high latitudes, with roughly one quarter of the outgassing directly associated with reduced solubility in the warming ocean, and the rest mainly linked with circulation changes and ocean stratification. This modification of air-sea O2flux plays an important role in estimating carbon uptake, as described in section 3.2.

The application of air-sea O2flux in CMIP6 provides a valuable complement for studies of O2-based global carbon sinks estimations under climate change. Our results reveal the significant increases of terrestrial and oceanic carbon sinks in the 21st century, reflecting the human impacts on the carbon cycle and Earth’s environments. The model biases of air-sea O2flux between CMIP5 and CMIP6 are also investigated in this study, which could lead to a total discrepancy up to 0.4 GtC yr-1in the estimations, indicating the importance of improvement of air-sea O2flux parameterizations in the model.

Some limitations should also be acknowledged. Our estimation of carbon sinks still suffers from relatively large uncertainties (0.4-0.8 GtC yr-1) due to the accumulations of uncertainty of each term in the calculations. Furthermore, the earliest observations of O2/N2we could obtain are from the late 1980s, which greatly limits the lengths of estimated time series. The comparisons between this study and Li et al.(2021) also reveal the importance of the accuracy of oxygen datasets on the carbon uptake estimations. Presently, we are working on structuring the global oxygen budget (Huang et al., 2018) under the constrain of O2/N2observations, from which we hope to extend the time series of atmospheric O2changes back to the 1900s as well as provide a more reliable oxygen dataset. Further explorations and investigations of the O2-based carbon uptake estimations should be done in the future.

Acknowledgements.The authors acknowledge the Scripps O2Program for providing the observations of atmospheric O2and CO2data. The authors also acknowledge the World Climate Recruitment Programme’s (WCRP) Working Group on Coupled Modelling(WGCM), and the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals (GO-ESSP) for producing outputs of CMIP6 model simulations. This work was jointly supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 41991231, 91937302) and the China 111 project (Grant No. B13045). The data processes and analysis are supported by Supercomputing Center of Lanzhou University.

Electronic supplementary material:Supplementary material is available in the online version of this article at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-021-1273-x.

Open AccessThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences2022年8期

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences2022年8期

- Advances in Atmospheric Sciences的其它文章

- COP26: Progress, Challenges, and Outlook※

- Climate Warming Mitigation from Nationally Determined Contributions※

- The Chinese Carbon-Neutral Goal: Challenges and Prospects※

- A Concise Overview on Solar Resource Assessment and Forecasting※

- Frontiers of CO2 Capture and Utilization (CCU)towards Carbon Neutrality※

- Changes in Global Vegetation Distribution and Carbon Fluxes in Response to Global Warming: Simulated Results from IAP-DGVM in CAS-ESM2※