ls there a role for liver transplantation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver?

Luis Cesar Bredt, Ingryd Betina Garcia Felisberto, Doroty Eva Garcia Felisberto

Luis Cesar Bredt, Surgical Oncology and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Unioeste University, Cascavel 85819-110, Paraná, Brazil

lngryd Betina Garcia Felisberto, Internal Medicine, Univates University, Lajeado 95914-014, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Doroty Eva Garcia Felisberto, Department of Surgery, Nossa Senhora das Graças Hospital, Curitiba 80810-040, Paraná, Brazil

Abstract Whether liver transplantation (LT) plays a role in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in non-cirrhotic liver (NCL) is a matter of debate. The recommendations for LT in this setting are extremely fragile and less welldefined than for cirrhosis-associated HCC. All reports of LT for NCL-HCC revealed that long-term outcomes of these patients are poor, and these dismal figures are justified by the advanced tumor stage at the time of LT, suggesting the presence of systemic micrometastatic disease. The decision-making regarding LT for NCL-HCC is difficult, since specific selection criteria are scarce, and basically the potential candidates are those with unresectable only-liver tumor at admission, or unresectable intrahepatic recurrence post-resection. Besides the surgical aspects regarding the tumor resectability, other phenotypic and genetic characteristics of the tumor should be considered for the indication of LT in this scenario. The present minireview aims to discuss and analyze the last series of LT for NCL-HCC, in order to help clinicians in the decision-making process regarding the role of LT in NCL-HCC treatment.

Key Words: Liver transplantation; Non-cirrhotic liver; Liver; Cancer; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Treatment

lNTRODUCTlON

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurs mainly in patients with liver cirrhosis, leading to chronic necroinflammation and hepatocellular regeneration. Nevertheless, HCC can arise in non-cirrhotic liver (NCL) in a proportion of cases that ranges widely from 7% to 54% across the geographic areas and according to the etiology of the liver disease[1-6]. The male predominance is less marked for HCC on NCL (75% men) than HCC on cirrhosis (85% men), and this sex ratio is equal in patients younger than 50 years[7]. These epidemiological data can be extrapolated for fibrolamellar (FL) HCC variant[8,9].

Authors have hypothesized distinct hepatocarcinogenesis in HCC with and without cirrhosis, although it would be an oversimplification to assume that NCL-HCC would occur in a totally healthy liver, because there is a wide range of parenchymal pathology without cirrhosis. In the last decades there was a progressive expansion of non-viral cases and namely of metabolic HCC in non-cirrhotic patients[10]. It has been reported that the role of alcohol intake is an independent predictor in noncirrhotic subjects with chronic hepatitis B virus infection of HCC development[11] and an extremely variable HCC recurrence risk and survival in successfully treated hepatitis C virus-infected patients[12]. Therefore, the histological background of NCL-HCC can include liver steatosis, hepatitis, genotoxic substances, metabolic diseases, germline mutations, and liver adenomas[13].

In general, NCL-HCC is detected at an advanced stage, and the diagnosis is made when clinical symptoms and signs related to the enlarged lesion appear, such as pain and abdominal discomfort, and a palpable tumor have occurred. Whereas the clinical presentation can be aggressive, distinct from HCC that occurs in a cirrhotic background, the preserved liver function in NCL-HCC scenario allows more extensive liver resections. Despite these high rates of R0 resections, the outcomes are dismal, and may be theoretically justified by the presence of systemic micrometastatic disease[14].

Differently from the extensive experience of referral centers with liver transplantation (LT) for the treatment of HCC in cirrhotic liver, the LT criteria for the treatment of NCL-HCC is not sharply defined, and actually is basically limited to situations in which resection is not possible. Moreover, while the survival rates of the larger group of HCC patients with cirrhosis treated with LT has been extensively published, there are few retrospective series regarding the prognosis and long-term survival evaluation of NCL-HCC after this treatment.

The present minireview aims to discuss and analyze the last series of LT for NCL-HCC, with special focus on the indications, prognostic factors and long-term outcomes, in order to help clinicians for decision-making regarding the role of LT in the NCL-HCC scenario on the basis of these analyses.

TECHNlCAL RESECTABlLlTY DETERMlNATlON

Despite the enlarged tumor burden, the preserved function of NCL generally offers the chance of performing extended liver resections safely, with totally acceptable perioperative mortality (0%–6%) and morbidity (8%–40%) of these patients[15-17].

One of the cornerstones for the indication of primary or rescue LT for NCL-HCC relies on the tumor's unresectability. The assessment of resectability differs from HCC in cirrhosis since the liver parenchyma is healthy or only minimally diseased. More extensive resections are feasible, therefore the resectability rates are higher. On the other hand, these tumors are often very bulky at presentation and are prone to vascular invasion of large vessels.

The surgical treatment strategy for both resection and LT should be directed towards R0 resection whenever possible, with both ‘oncological’ (prognostic) and ‘technical’ (surgical) criteria being considered. The technical unresectability does not always mean that the LT is indicated, because unfavorable prognostic criteria may preclude patients from succeeding even with LT.

Initially the first attempt would be the work-up for any evidence of extrahepatic disease, such as metastasis to lymph nodes, lung, or bone, that would be a formal contra-indication for both resection and LT. The evidence of homolateral or contralateral satellite nodules denotes widespread intra-hepatic dissemination. It is crucial that an accurate assessment of tumor vascular relationships, the evaluation of the intersection of the hepatic veins with the inferior vena cava must be done, and an eventual tumoral thrombus in the portal vein trunk or branches may preclude the resection. Finally, the quality of the underlying liver parenchyma should be accessed with estimation of the future liver remnant, that would be insufficient despite no underlying cirrhosis[18].

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES AFTER LT FOR NCL-HCC

For all the wide indications of LT, they must have comparable outcomes. If a strict disease does not, then it must cause no undue prejudice to other recipients with a better prognosis[19]. The Milan criteria conception is the ideal example for this statement, and the current benchmark for LT for HCC in cirrhotic patients, because the overall 5-year survival rate of 65%–78% for Milan-in patients[20] is similar to 70%–82% survival for benign indications. In general, a 5-year overall survival rate of > 50% is recommended by the liver-transplant community in the face of liver grafts scarcity[21]. Thus, the indication of LT for NCL-HCC must be comprehensively analyzed.

Liver resection is currently the best upfront therapy for NCL-HCC[22-24]. However, in this section the role of LT in the setting of unresectable HCC at presentation or because of tumor recurrence following resection will be discussed. There is limited literature that reports the long-term survival of the subgroup NCL-HCC patients treated by LT, and the available series (Table 1) have limitations, mainly because of its retrospective and eventually multicenter design, and in some cases the reduced number of patients.

Table 1 Selected series that addressed the long-term survival of patients with non-cirrhotic liver - hepatocellular carcinoma treated with primary or rescue liver transplantation

A systematic review that included all very early reported cases of LT for NCL- HCC from 1966 to 1998 revealed poor long-term outcome of these patients. The 5-year survival rates were 11.2% for non-FL-HCC and 39.4% for FL-HCC[24-26]. In the most recent series with 105 NCL-HCC transplant patients reported by Mergentalet al[27] a 5-year overall survival of 49% was observed. For 62 patients, LT was the primary treatment with a 5-year overall survival of 43%, and for 43 patients, LT was a rescue treatment after resection, with a 5-year overall survival of 58%. Pathological data showed more favorable tumor characteristics in the rescue-LTs compared to primary-LTs (TNM staging, median size of largest tumor, number of patients Milan-in, and number of patients with serum alpha-fetoprotein level < 100 ng/mL). Rescue-LT within 12 mo after resection was the significant predictor for long-term survival.

A specific question must be addressed regarding FL-HCC, which historically the patients with FLHCC appear to have a better prognosis, as shown by Houben and McCall[24]. Kakaret al[28] clearly showed that the outcomes of FL-HCC and NC-HCC are similar when same-stage diseases are considered and when the proliferative activities of these tumor variants (Ki-67) are similar[23,26]. Enlarging cohorts, including non-FL and FL-HCC with no distinction, would allow better predictions of the role of LT in patients with NCL-HCC. The analysis of the larger will be a major step forward to a better insight of the indication for LT in this scenario[14].

SELECTlON OF CANDlDATES FOR LlVER TRANSPLANTATlON

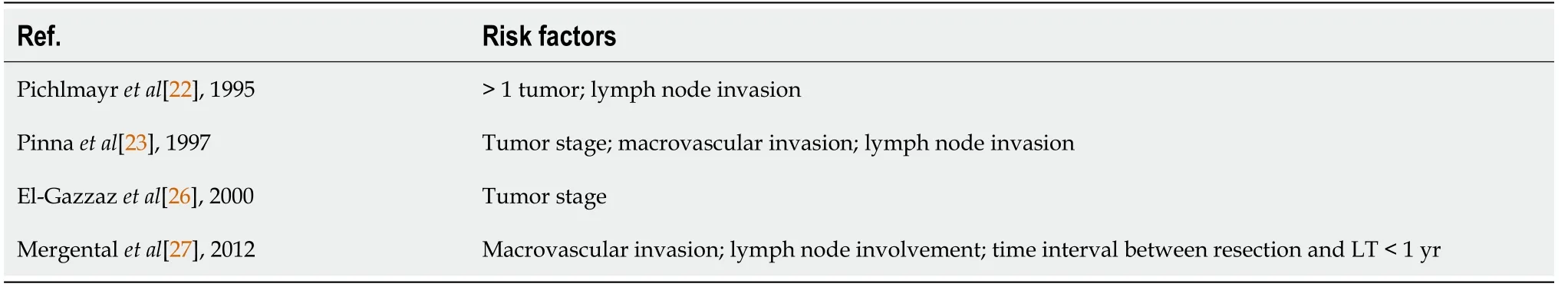

The risk factors for recurrence rate after resection could be very helpful in identifying NCL-HCC candidates for LT[14]. Authors have already hypothesized tumor characteristics that would be potential prognostic factors for recurrence after LT (Table 2). The small number of patients within these series, however, leads the conclusions from these studies to be handled with caution.

Table 2 Series of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver treated with liver transplantation with reported risk factors for poor prognosis

According to Mergentalet al[29], lymph node invasion and macrovascular invasion were suggested to be the main predictors of recurrence after LT. Later, the same author also showed that a time period of less than 12 mo between the previous resection and tumor recurrence was a significant risk factor for poor survival. This short time span probably would reflect a more aggressive biology[27].

Data on 4373 non-cirrhotic HCC patients who underwent LT for NCL-HCC from a large database were analyzed using logistic regression model and life table methods. The identified factors that significantly related to survival were the total number of tumors, extrahepatic disease, nodal involvement, satellite lesions, vascular invasion, tumor grade and pre-LT treatment[30].

The identified variables for poor prognosis in the published studies are based on the pathological analysis of the explanted livers. Furthermore, the goal would be the evaluation of the predictors before the LT indication, such as tumor imaging at listing, lymph node involvement, the response to previous treatments, and the kinetics of the tumor growth. In the case of rescue-LT patients, the imaging characteristics before resection and the pathological characteristics of the resected tumor are crucial to assess candidates for LT at the time of recurrence[19].

The suggested favorable prognostic factors[19,23,27] such as alpha-fetoprotein level (< 100 ng/mL), tumor number (< 4), tumor diameter (< 5 cm) and no vascular and node involvement assessed on imaging at listing, would refine the selection of patients for LT for NCL-HCC, decreasing therefore, eventual futile procedures.

PROGNOSTlC GENETlC lNFORMATlON ON NCL-HCC

Recently, genetic information regarding NCL-HCC prognosis can ultimately aid the selection of candidates for LT. Clinical data analysis indicated that increased PKM2 expression in NCL-HCC was correlated with tumor vascular invasion and intrahepatic metastasis, and positive PKM2 expression was an independent poor prognostic factor for recurrence[31]. Some studies have found that the level of activity regulator of SIRT1 in NCL-HCC is significantly correlated with tumor size, vascular invasion, and tumor differentiation, consequently with disease-free survival rates[32].

MiRs are 18–25 nucleotide noncoding RNAs that can regulate gene expression. A high expression of hsa-mir-149 was found to be a risk factor for poor prognosis, and an increased hsa-miR-23c expression was associated with improved survival in patients with HCC-NCL[33]. Similarly, miR-21 levels are generally increased in HCC-NCL[33,34].

CONCLUSlON

The recommendations for LT in this setting of NCL-HCC are fragile and less well-defined than for cirrhosis-associated HCC. The decision-making for LT is still difficult, since specific selection criteria are scarce. Resection must be the upfront therapy for these patients, and LT must be offered only for patients with recurrence after resection or with unresectable disease at presentation. However, besides technical unresectability, other phenotypic and genetic characteristics of the tumor should be considered for selecting patients for LT in the NCL-HCC scenario, avoiding futile procedures.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:All authors contributed equally to this review article; all authors equally contributed to this paper with conception and design of the study, literature review and analysis, drafting and critical revision and editing, and final approval of the final version.

Conflict-of-interest statement:No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Brazil

ORClD number:Luis Cesar Bredt 0000-0002-8487-1790; Ingryd Betina Garcia Felisberto 0000-0003-3621-9525; Doroty Eva Garcia Felisberto 0000-0002-1693-0566.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Liu JH