SINGAPORE’S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT DEBATE:TIME FOR CHANGE?

Hu Yukun

Singapore executed twomen in one month inthe spring of 2022 fordrug offenses, markingthe resumption of thedeath penalty in thecountry after a pauseof more than twoyears. The executions stimulated unusual abolitionist sentiment in Singapore as well as international concern, especially the execution of a 33-year-old Malaysian national.

Capital punishment has quite a long history in Singapore, dating back to the days before its independence, and with public support it remains applicable in practice for certain categories of offenses. However, winds of change could be sweeping through Singaporean society as capital punishment seems far more controversial than it once was.

A Century-Long British Legacy

International attention suddenly turned to Abdul Kahar bin Othman, a 68-year-old Singaporean, when he was hanged for drug trafficking on March 30, because no executions had been carried out in Singapore since 2019. Less than a month later, a second death row prisoner, Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam, was executed, further embroiling the country in controversy.

But capital punishment was notestablished by the Singaporean government. When Singapore was the capital of the former Straits Settlements and a subsequent “crown colony” in the 19th Century, the death penalty was introduced by the United Kingdom. When Singapore became independent in 1965, capital punishment had not yet been abolished in the United Kingdom, and this British legacy was inherited, becoming an integral yet controversial facet of the country’s criminal law.

Therefore, Singaporean procedures are quite similar to those formerly used in the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. Even the sole method of execution, hanging conducted at dawn by a long drop, was introduced from the United Kingdom in 1872 by William Marwood.

While retaining the death penalty, Singapore has been narrowing its application. In 2012, it further amended the law to exempt some cases from a mandatory death sentence. Today, capital punishment is applied only to certain categories of crimes including murder, drug-related crimes, and some firearmrelated offences stipulated in the Penal Code and four Acts of Parliament.

Since an amendment of the Criminal Procedure Code 30 years ago, all capitalcases have been heard by a single judgein the High Court of Singapore. Afterconviction and sentencing, the offender can choose to make an appeal. If theappeal is rejected, the only remaininghope for recourse is the President ofSingapore, who has the power to grantclemency, as advised by the Cabinet.

Before 1994, offenders could also file civil or criminal appeals to the UnitedKingdom’s Privy Council in Londonif they had exhausted all the appealmethods in Singapore, but today allthe chances of overturning the deathsentence are within the country, andsuccessful applications have been rare.

While expanding enforcement of the death penalty, the country has addedmore exemptions in the past decade.Alongside underaged, pregnant, andoffenders of unsound mind, criminalswho commit murder without intentto kill are also usually exemptedfrom hanging, but sentenced to lifeimprisonment with mandatory caning instead. Judges’ discretion also applies to offenders convicted of drug trafficking. Death sentences exemptions also usually include offenders who acted only as couriers, those who substantively assist Singaporean authorities, and those with mental disabilities.

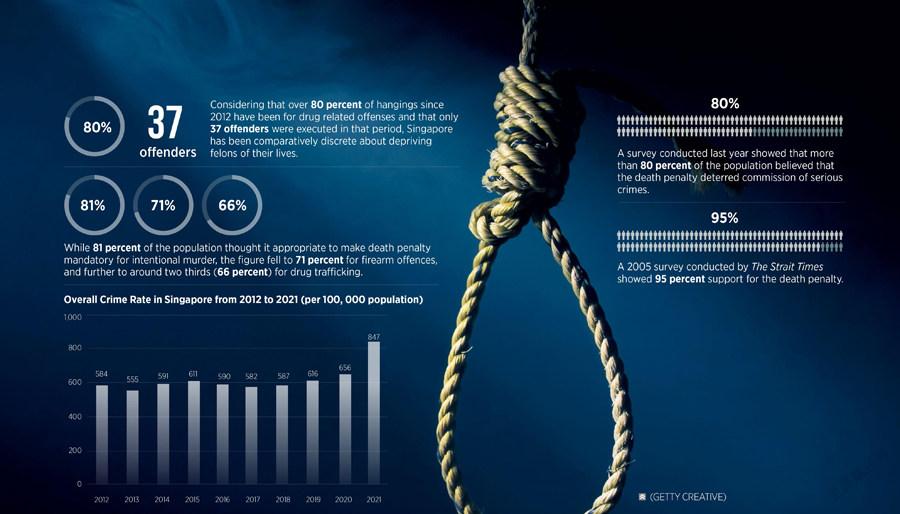

Considering that over 80 percent of hangings since 2012 have been for drug related offenses and that only 37 offenders were executed in that period, Singapore has been comparatively discrete about depriving felons of their lives.

More importantly, the low crime rate in this city-state (847 per 100,000 residents in 2021) could explain why maintaining this British “legacy” still has such strong support from a majority of Singapore residents. According to the country’s Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam, a survey conducted last year showed thatmore than 80 percent of thepopulation believed that the deathpenalty deterred commission ofserious crimes.

Among the many reasons,analysts believe that theChinese-majority society isheavily influenced by thetraditional Chinese view thatharsh punishment deters crime,restores normalcy, and maintains“Confucian peace and harmony.”

“An inherited value systemthat sees hard, heavy punishmentas a solution is at the coreof Singapore’s resistance toabolishing the death penalty oreven agreeing to a moratoriumon executions,” said Vanu Menon,former Permanent Representativeof Singapore to the UnitedNations.

If applied sparingly, seeminglya contributor to Singapore’sreputation as one of the world’ssafest countries, and stronglysupported by the public, theformer British colony seems tohave every reason to keep thisBritish legacy even though the UKhas already abandoned it. It wasquite unexpected that the twoexecutions this spring stirred upsuch a negative public reaction.

Understated but GrowingDissent?

For a long time, public debateon the death penalty was hardlyheard in Singapore and usuallyalmost non-existent. Yet whensome Singaporeans become moreoutspoken in opposition to capitalpunishment, the phenomenonis not out of nowhere, because“public support isn’t asoverwhelming and unshakeableas the government often portrays it to be,” according to Kirsten Han, a Singaporean journalist and social activist who spent a decade campaigning against the death penalty.

Even in the findings cited by Mr. Shanmugam in the Parliament of Singapore during his ministry’s Committee of Supply debate, public opinion still varies regarding capital punishment for different offences: While 81 percent of the population thought it appropriate to make death penalty mandatory for intentional murder, the figure fell to 71 percent for firearm offences, and further to around two thirds (66 percent) for drug trafficking.

Yet drug-related offences have been the super majority of death penalty cases and have received the least public support in recent years. What’s more, support for capital punishment in general has been declining steadily: A 2005 survey conducted by The Strait Times showed 95 percent support for the death penalty.

Even today’s supporters are often more inconsistent in their position. In 2016, four scholars from National University of Singapore, Singapore Management University, and MARUAH Singapore conducted an in-depth survey and found a large difference between the proportion of respondents who thought death penalty appropriate in various scenarios compared to support for the death penalty in the abstract only.

On drug trafficking, 87 percent of the 1,500 surveyed supported death penalty in principle; when it comes to specific cases, the share of death penalty supporters decreased drastically to 29 percent.

The scenarios surrounding the execution of both Abdul Kahar and Nagaenthran were fairly sympathetic to most Singaporeans, which contributed to the growing abolitionist sentiment and kindledwidespread public debate on thedeath penalty itself.

The issue of human rightsalways comes first in such debate.After the violation of the right tolife, the most glaring issue in theeyes of abolitionists has been theharsh living conditions for thoseon the death row at Changi Prison, which has been criticized by local activists for its small size, hot andhumid environment, lack of clean water and sunlight, and poorventilation. Such conditions have been shown to be detrimental tothe emotional and mental healthof the death row prisoners.

For many Singaporeans,neither of the cases against Abdul Kahar or Nagaenthran providedreasonable grounds for deathsentence.

Abdul Kahar struggled withdrug addiction since his teenageyears, and he and his family never received substantial assistancefrom society such as sustainabletreatment, counseling, or support to reintegrate into society. “Instead, all Abdul Kahar received was punishment in the form ofincarceration that only served tofurther alienate him from society and subject him to stigma,” saidHan.“And now he’s gone.”

Nagaenthran was on the deathrow for eleven years before hisexecution on April 27 due to amoratorium pending judicialchanges of the mandatory deathpenalty laws. The reason for theinternational outcry over his death sentence mainly focused on hislow IQ of 69 and an assessmentby a psychiatrist defining him asmentally impaired to an extentthat he should not be held liableto his crime and execution.

Still, a more importantargument is always aboututilitarianism: Is death penaltyreally more effective than anyother punishment in deterringdrug offenses and other felonies?

The Singapore governmenthas been insisting on theefficacy of capital punishmentas its justification, but a growingnumber of Singaporeans are nowquestioning, challenging, andeven dismissing the dominantnarrative. The issue has beendebated globally at great lengthto no conclusive end. And itwould be implausible to conductscientific control on such an issue.

For abolitionists, one thing iscrystal clear: There is no remedyfor a wrongful execution.

Growing dissent against thedeath penalty is unprecedentedlyvisible in Singapore, but thegovernment is not expected tomake a U-turn from its long-standing stance. However, on acase-by-case basis, the country’salready discrete judiciary willhave to be even more cautiousin practice after such intensescrutiny from local society andthe international community.