Antibiotic-free antimicrobial poly (methyl methacrylate) bone cements: A state-of-the-art review

lNTRODUCTlON

Regardless of the patient group, periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a relatively rare occurrence; for example, 2 years after total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA), the cumulative incidence rate is on the order of between 0.5% and 0.8% and about 1.0% of cases, respectively[1,2]. Nonetheless, PJI is recognized as being the most challenging of complications of total joint arthroplasties (TJAs) (to the point of intractability) because of the associated risk for revision of the implant, increase in mortality, increase in morbidity, decrease in quality of life of the patient, and increased direct and indirect costs[3,4]. As such, PJI has been the subject of myriad studies, the bulk of which has been devoted to four aspects, these being identification and stratification of patient- and surgery-based risk factors, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment/management[4]. Among risk factors, the significant roles of morbid obesity (body mass index greater than 40 kg/m), young age (< 50 years) of the patient, preoperative use of opioids by the patient, and prolonged surgery time (> 2 h) are recognized even though the supporting clinical evidence ranges from limited to moderate[5-8]. With respect to diagnosis, an assortment of methods is in current clinical use, such asF-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)[9], and measurement of synovial fluid biomarkers, notably, alphadefensin[10], or under investigation, among which are measurement of temporal change in D-dimer level in conjunction with serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level[11], use of monocyte/lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and platelet/mean platelet volume ratio (PVR), in conjunction with other hematologic and aspirate markers[12], and landmark-guided hip aspiration[13]. To date, a gold standard has not emerged. The most widely used prevention method is anchoring the implant in a bed of antibiotic-loaded poly(methyl methacrylate) bone cement (ALBC)[4]. As for treatment/management, the two common approaches are: (1) Surgical debridement (debridement followed by intravenous or highly bioavailable oral delivery of antimicrobial medication specific to the microorganism found in the case (medical therapy) and retention of the implant (DAIR)[14,15]); and (2) Resection arthroplasty using two-stage exchange[16,17] (although, in recent years, in some countries, enthusiasm is being shown for one-stage exchange[18,19] followed by medical therapy[4,16]). In either option, it is common to fix the exchanged implant to the contiguous bone in an ALBC bed[16].

While an ALBC has a number of attractive features, chief among which are ease of preparation in the operating room and low intrinsic toxicity, it has its share of shortcomings and concerns. One shortcoming is its lack of bioactivity[20,21]. Another is the fact that the bacterial species that are responsible for PJI, most commonly,and[22], are becoming resistant to gentamicin sulfate, which is the antibiotic in the vast majority of ALBC brands approved by national regulatory bodies, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (the method of mixing of the antibiotic with the cement powder is proprietary) and physician-directed ALBC formulations (mixing of antibiotic and cement powder is carried out in the operating room)[4,23]. A third shortcoming is that the release profile of the antibiotic is sub-optimal, being characterized by 1) an initial short high release rate (zone lasts, typically, < 2 d), followed by a significant reduction in release rate, culminating in exhaustion of release after, typically, 20-30 d and 2) cumulative release of only, typically, between about 0.3% and about 13% of the loaded antibiotic[24,25]. Additionally, there is a lack of consensus that even with riskstratified usage in primary TJA, the current generation of ALBCs is efficacious and cost-effective[26-36]. As for concerns about ALBC, there are long-standing ones, such as potential deleterious effect on mechanical properties of basis cement[37], and ones that have only recently been raised, such as an increase in immunological factors (specifically, soluble interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein) in patients in which there is a gentamicin-loaded cement implant, suggesting that unknown immunomodulatory pathways may be altered by an ALBC[38].

The aforementioned observations highlight the need for novel methods for reducing the risk for PJI whether ALBC is used as a prophylactic agent in primary THAs and TKAs (as is common practice in a number of countries, such as Norway, and limited use in others, such as United States) or during the second stage of a two-stage exchange arthroplasty (as is common practice in the United States[39]). This need has served as the driver for the large amount of research attention that has been given to this field. These efforts may be grouped into four approaches: application of an antimicrobial coating to part(s) of implant component(s), such as the proximal zone of the femoral stem of a THA[4,40-45]; use of ALBCs in which a relatively new antibiotic/antibacterial compound (for example, daptomycin[46] or a secondgeneration lipophosphonoxin[47]) is added to the cement powder; modification of the surface of the implant (for example, incorporation of an antibiotic-releasing polymer into the surface of a joint implant[48] and use of a nanofabrication method to create biomimetically-inspired nanostructures on an implant surface[49]); and proposed use of antibiotic-free antimicrobial PMMA bone cements (AFAMBCs)[50-68]. The focus of the present review is AFAMBCs, which have been the subject of many studies on their formulation and characterization[50-68]. However, to date, only one review of this body of literature has been published[69] but it has two shortcomings. First, only about half of that review was devoted to AFAMBCs, with the balance being on aspects such as PMMA bone cement and orthopaedic infections in general and details of the classification, diagnosis, and treatment of PJI. Second, some of the literature studies reviewed were not appropriate to bone cement use in TJAs; for example, the subject of the studies was cement for beads, blocks, and spacers for the treatment of severely contaminated open tibial fractures[70], bone reconstruction[71,72], cement used for stabilizing/augmenting fractured osteoporotic vertebral body fractures (for example,vertebroplasty or balloon kyphoplasty)[73], and antibacterial coatings[74].

The present work focuses exclusively on the literature on AFAMBCs for long-term load-bearing TJA applications (as such, it excludes its use in spacers and blocks), giving a comprehensive and critical review of this body of knowledge by not only summarizing key results (with special emphasis on evaluations of antimicrobial efficacy and cytotoxicity) but, also, highlighting attractive features and shortcomings of literature studies. The latter feature should point to opportunities for future research in the field. This review should inform discussion of the potential for use of AFAMBCs to replace ALBCs.

LlTERATURE STUDlES

Antimicrobial activity

The activity of a bone cement, in which the powder additive comprised NanoSilver particles (silver particles, of size 5-50 nm and porosity 85%-90%) (loading between 0% and 1%), when tested against a clinical isolate of MRSE showed loading dependency, with increased loading of the additive leading to increased activity; specifically, cement having a loading of 1% of the additive producing complete inhibition of proliferation of the bacterial strain. As a reference, uninhibited proliferation of the strain occurred when an approved ALBC brand (that contained 2% gentamicin) was used[50]. This same comparative trend was found when 1% NanoSilver-loaded cement was compared with the approved ALBC brand when a clinical isolate ofwas used[50].

Chitosan (CS) nanoparticles (CS-NPs) (diameter: 220 ± 3 nm) were prepared using the ionic gelation method and quaternary ammonium chitosan (QCS) was synthesized by the method presented by Huh[75] QCS NPs (mean diameter: 284 ± 2 nm) were obtained from QCS in the same manner as was done for CS-NPs. Two approved plain ALBC brands and two approved ALBC brands were used as negative and positive control cements, respectively. Two sets of experimental AFAMBCs were formulated, one by adding CS-NPs to the cement powder and the other by adding QCS-NPs to the cement powder[51]. Against bothand, each of the AFAMBCs showed significant improvement in antimicrobial activity compared to a control cement, but with QCS-NP-loaded cement showing significantly higher activity than the CS-NP-loaded cement[51]. These results were attributed to the fact that the NPs provide a high surface charge density for interacting with and disrupting bacterial cell membranes[51].

An experimental AFAMBC was obtained by mixing a monomer of quaternized ethylene glycol dimethacrylate piperazine octyl ammonium iodide (QAMA) into the liquid of an approved plain ALBC brand (10, 15, and 20 wt/wt%) (designated PMMA-10QAMA, PMMA-15QAMA, and PMMA-20QAMA cements, respectively)[52]. While() was retained on the surface of plain cement specimens, there was no evidence of retention and aggregation on experimental AFAMBC specimens. The antimicrobial action displayed by the AFAMBCs was attributed to the presence of QAMA, a polymerizable monomer that has an irreversibly bound component[52].

Using a novel synthesis route, Ag nanoparticles (AgNPs) with very well controlled geometrical properties and stability were obtained and, then, these particles were capped with tiopronin (TIOP), an agent that allows binding of other compounds to the nanoparticles[54]. These nanoparticles (AgNPs-TIOP) were added to the powder of a plain PMMA bone cement (0.1%, 0.5%, and 1.0%)[54]. Against gram-positive methicillin-resistant(MRSA), the difference in growth rate of the bacterial strain when specimens of the experimental AFAMBC (1% of mean diameter 11 nm Ag-TIOP nanoparticles) and those of a control cement (no Ag nanoparticles) were used was not significant but the lag time (directly related to resistance to growth of the bacterial strain) of the AFAMBC was approximately 12 times longer than that the control cement specimens were used, indicating the better antimicrobial performance of the former cement[54]. Although the exact mechanism responsible for the antimicrobial activity of Ag nanoparticles has not been established, many explanations have been put forward. Examples are uptake of free Ag ions followed by disruption of the production of an energy storage molecule (adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) and replication of DNA[76]; inactivation of the bacterial cell (cell membrane and enzymes) by the Ag ions interfering with enzymes that interact with sulfur in the protein chains and/or generating reactive oxygen species[54], which kill the cells; and Ag ions causing separation of paired strands of DNA in the bacteria[77].

A bioactive glass (SiO-NaO-CaO-PO-BO-AlO-AgO) was produced by melting the reactants in a Pt crucible at 1450C, then quenching the melt in water to obtain a frit that was milled and sieved to yield glass powder (SBAG powder) (grain size < 20 mm)[55]. An experimental AFAMBC was obtained by mechanically mixing SBAG powder with the powder of an approved plain cement brand (loading: 30% and 50%), with two brands being used as control, one classified as low-viscosity (LV) and the other high-viscosity. Against, a small drop in both proliferation and adhesion were observed when an AFAMBC rather than a control cement was used, with the same trends being seen in the values of the McFarland Index[55]. In an inhibition halo test, as expected, the size of the halo zone when AFAMBC specimens were used decreased with length of time of contact of the specimens with the agar substrate but, importantly, at the end of the 2nd day, the inhibition zone measured between approximately 1.0 and approximately 1.5 mm, indicating that the antibacterial capability of the cements is good[78,79]. The antimicrobial activity of a bioactive glass has been attributed to an increase of aqueous pH and osmolarity in thezone that surrounds the glass, which accompanies the dissolution of the glass[80], and deposition of glass debris on the surface of the bacteria[81].

Organic nanoparticles containing propylparaben were prepared by fast simultaneous removal of solvents and water from a volatile oil-in-water microemulsion composed of polypylparaben,-butyl acetate, iso-propyl alcohol, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and water, resulting in a fine powder composed of propylparaben nanoparticles (16 wt/wt%), SDS (45 wt/wt%), and PVP (39 wt/wt%)[56]. An AFAMBC was formulated by adding this fine powder to the powder of an experimental plain bone cement formulation (0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, and 7%). Overall, against a given bacterial strain (, MRSA, or), the duration of the lag phase increased but the growth rate (GR) decreased with increase in concentration of nanoparticles in the AFAMBC[56]. These trends suggest that the antimicrobial effect of the AFAMBC is a consequence of the conjoint reduction of viable microbial population and the viable cells not exhibiting the same phenotype of the cells in contact with the nanoparticles[56].

Fifth, in only a few studies was a human cell line used in the evaluation of cytotoxicity of the cements[50,52,64-66,68]. To give studies clinical relevance, use of a human cell line is preferred to use of cell lines from animals, such as mouse fibroblast.

The king often lost his patience, and was determined8 to see his daughter, but the queen always put him off the idea, and so things went on, until the very day before the princess completed her fourteenth year

An AFAMBC was formulated by mixing commercially-available Ag nanoparticles (diameter: 30-50 nm), which had been surface-functionalized with polyvinylpyrrolidone (0.2 wt/wt%) to aid dispersion and minimize agglomeration of the particles, into the liquid of an approved plain cement brand or an approved ALBC brand (loading ratio: 0.25%, 0.50%, and 1.0%, relative to mass of its powder) using an ultrasonic homogenizer with a solid Ti tip[58]. Using a modified Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion assay, it was found that against each of the bacterial strains used (commercially-availableandand 4 clinical isolates obtained from patients with active PJIs (2and 2s)), none of the AFAMBCs demonstrated antimicrobial activity (that is, there was a large area of bacterial colony growth) while the positive control (an approved ALBC brand; antibiotic: gentamicin) exhibited large zones of inhibition (about 18-39 mm)[58]. Similar trends were found in the results of studies in which time-kill assays against planktonic bacteria were performed[58]. However, results of bacterial adhesion tests showed that each of the AFAMBCs significantly reduced biofilm formation relative to the plain cement[58]. These results suggest that while the AFAMBCs have no antimicrobial activity against planktonic bacteria, they have good potential for use in cases where prevention of bacterial adhesion is needed (for example, in primary TJAs)[58]. It is to be noted that: (1) Many of the bacteria commonly involved in PJI, such as, produce a biofilm, which is a community of microorganisms embedded in an organic polymer that mainly is composed of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA and lipids, that adheres to an implant surface[82]; (2) A biofilm allows planktonic cells to change their mode of growth to the sessile form[82]; and (3) It is expected that a biofilm will protect the dividing bacteria from the action of an AFAMBC[82,83].

An experimental AFAMBC was formulated by adding a first-generation quaternary ammonium dendrimer of tripropylene glycol diacrylate (TPGDA G-1) to the liquid of a commercially-available plain bone cement (5, 10, 15, or 20 wt/wt%)[59]. Against a commercially-availablestrain, the mean antimicrobial efficiencies of 5TPGDA cement and 10TPGDA cement were 45% and 100%, respectively, compared to a negligible amount for the plain cement counterpart[59]. The antimicrobial action of the quaternary ammonium dendrimer was attributed to it breaking the wall and membrane of the microorganism[59].

A bioactive glass (SiO-NaO-CaO-PO-BO-AlO) was produced by melting the reactants in a Pt crucible at 1450C for 1 h, then quenching the melt in water to obtain a frit that was milled and sieved to yield glass powder (SBA2 powder) (grain size < 20 mm)[60]. This powder was then subjected to an optimized ion-exchange process in aqueous solution of AgNO, after which the silver-doped powder was dried in air at 60C (Ag-SBA2 powder). The experimental AFAMBC was obtained by mechanically mixing 30 wt% of Ag-SBA2 powder with the powder of an approved plain cement brand (Ag-SBA2 cement), with three approved plain PMMA cement brands being used as controls. Against a commercially-available stock of, 1) a significant drop in both proliferation and adhesion were observed when the AFAMBC rather than a control cement was used, trends that were also seen in the values of the McFarland Index; and 2) in an inhibition halo test (Kirby-Bauer test), the size of the halo zone when AFAMBC specimens were used was between approximately 2.5 and approximately 3.0 mm[60].

On L929 mouse fibroblasts, the difference in release of lactate dehydrogenase (an indicator of cell integrity) when an experimental AFAMBC (NanoSilver-loaded cement) was usedwhen an approved ALBC (control cement) was used, in a non-toxic cell culture medium, was not significant, a trend that was also observed both with protein content and number of vital cells, all of which showed that the lack of cytotoxicity of the AFAMBC[50]. Furthermore, on a human osteoblast cell line (hFOB), only a few dead osteoblasts were seen in live-dead staining in the NanoSilver bone cement specimens and osteoblasts that grew on these specimens were, in the main, vital and grew in a mesh-like manner, as just as in the cell culture medium, showing that the cement has high biocompatibility[50]. The results were explained in terms of Ag ions binding to cellular structures in the bacterial strain (especially, to their SH- groups), thereby interfering with the integrity, energy production, and conservation of the bacterial cell[50]. In contrast, bacterial resistance to the antibiotic in the control cement (gentamicin), being an aminoglycoside, can be acquired by single point mutations [50].

Cheap? I peeked14 through some women’s sweaters. My daughter was holding up a pair of pink polyester pants that had been on the clearance15 rack since day one.

A bioactive glass (SiO-NaO-CaO-PO-BO-AlO) was produced by melting the reactants in a. Pt crucible at 1450C for 1 h, then quenching the melt in water to obtain a frit that was milled and sieved to yield glass powder (SBA3 powder) (diameter < 20 mm)[62]. This powder was then subjected to an optimized ion-exchange process in a copper-containing aqueous solution, after which the Cu-doped powder was washed, filtered, and dried in air at 60C (Cu-SBA3 powder). An experimental AFAMBC was obtained by mechanically mixing 10 wt% of Cu-SBA3 powder with the powder of an approved plain cement brand, with three approved plain PMMA cement brands being used as controls[62]. Againstbiofilm, a significant drop in bacteria viability was observed at each assayed timepoint when an AFAMBC rather than a control cement was used (by a factor of between 2 and 4), indicating that the antibacterial potential of the AFAMBC is good[62]. The antibacterial action of the Cu-SBA3 cements was explained in terms of participation of reactive hydroxyl radicals that are generated in reactions that are harmful to cellular molecules, such as oxidation of proteins[77]. Notwithstanding these results, the resistance of some bacterial species, such as, against copper-containing biomaterials, was noted[62].

A bioactive glass (SiO-NaO-CaO-PO-BO-AlO) was produced by melting the reactants in a Pt crucible at 1450C, then the melt was quenched in water to obtain a frit that was milled and sieved to yield glass powder (SBA2 powder) (grain size < 20 mm or 20-45 mm)[63]. This powder was subjected to an optimized ion-exchange process in aqueous solution of AgNO, after which the silver-doped powder was dried in air and stored (Ag-SBA2 powder). An experimental AFAMBC was obtained by mechanically mixing 15 or 20 wt% of an Ag-SBA2 powder with the powder of an approved plain cement brand. Several combinations of process variables for producing the powder (drying temperature, storage mode, and mixing temperature) were used, resulting in 8 variants of powders. In an inhibition halo test in which a commercially-availablestrain was used, the size of the halo zone when AFAMBC specimens were used was between approximately 2 and approximately 4 mm, indicating marked antibacterial activity of these cements[63].

An AFAMBC was prepared by incorporating sheets of CS and/or graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets, synthesized using the protocols given by Mangadlao[84], into the liquid of an experimental plain PMMA bone cement (CS- and GO-based cements)[64-66]. A plain cement served as the control cement. Against a commercially-availablestrain, after 24 h incubation, the cements containing 0.2% GO (ABC-0.2GO cement), 0.3% GO (ABC-0.3GO cement), 0.5% GO (ABC-0.5GO cement), or 15% CS (ABC-15CS cement) showed significantly higher antimicrobial activity compared to that of the control cement[64,65]. Two mechanisms were postulated to explain the antimicrobial activity of the GO-based cement[64]. First, GO sheets directly contact the bacterial cell, thereby damaging them. Second, reactive oxygen species that are produced destroy the cell membrane subsequent to the GO sheets contacting the surface[64,65]. Synergistic antimicrobial activity was demonstrated in the cement that contained 0.5% GO and 15% CS (ABC-0.5GO-15CS cement)[64].

But the clever flute-player was quite a match for the little man in cunning, and said: All right, you needn t be afraid, you shall get your beard back before we part; but you must allow my bride and me to accompany you a bit on your homeward way

An experimental AFAMBC formulation (PMMA-NAC cement) was obtained by adding N-acetylcysteine powder (NAC) (an antibacterial agent) to PMMA bone cement in loadings ranging from 10 to 50% wt/vol[67]. At NAC loading ≥ 20% wt/vol, the antibacterial efficacy of the NAC-PMMA cement against planktonic forms ofandwas significantly greater than that of the control cement (an approved plain cement brand). The same trend was seen against biofilm forms of the same bacterial strains.

Two variants of an experimental AFAMBC were prepared, the first one by mixing particles of a 5 wt/wt% of a bioglass (BGII-0.4; grain size: ≥ 40 mm), Ag NP powder (particle size: approximately 50 nm) (1.5 wt/wt%), and the powder of an approved plain cement brand (BC-BGII-0.4-AgNP cement)[68]. BGII-0.4 was prepared using the Stober method modified by Zheng[85]. The composition of the other variant was the same that of the first one with the exception that a different bioglass was used (a sol-gel obtained SiO/CaO (70/30 mol%) bioglass; grain size: about 300 nm) (BG-MP)[68]). The antibacterial performance of each of the AFAMBC variants was determined in two tests using a hospital strain of: inhibition of the growth of the strain after 4 h and effectiveness (methicillin resistance). In each of these tests, the BC-BGII-0.4-AgNP cement showed significant improvement compared to the control cement (an approved plain cement brand)[68].

In vitro cytotoxicity/cytocompatibility

An AFAMBC was formulated by mixing commercially-available gold nanoparticles (Au NPs; 99.95% purity; diameter: 10-20 nm) with the powder of an approved plain bone cement brand (loading: 0.25, 0.50, and 1.00 wt/wt%)[61]. Against clinical isolates of MRSA, 1) live bacterial cells were reduced by up to approximately 55% on specimens of cement containing 1 wt/wt% Au NPs compared to specimens of the control cement (no loaded Au NPs); and 2) three-dimensional reconstruction of the biofilm showed a drop of biofilm thickness by approximately 74% when an ALAMBC was used[61].

On mouse fibroblast cells (3T3), the difference in cytotoxicity between an experimental AFAMBC (15% CS-NPs or 15% QCS-NPs added to cement powder) and a negative control cement was not significant[51]. There was good adherence of cells (a commercially-available human osteosarcoma cell line; HOS TE85) on specimens of PMMA-15QAMA cement after 1 wk, indicating cytocompatibility of the cement[52].

On osteoblast cells (MC 3TC), the difference in cytotoxicity between the Ag nanoparticles-tiopronin cement and the control cement (an approved plain ALBC brand) was not significant, regardless of the nanoparticles loading of the cement[54].

On osteoblast cells (MC-3T3), the difference in cytotoxicity between an experimental AFAMBC (contained Ag NPs-TIO) and a counterpart control cement (same composition but no Ag NPs-TIO) was not significant regardless of the duration of exposure to the cells[56]. On osteoblast cells (MC-3T3), the difference in cytotoxicity between an experimental AFAMBC (contained the Ag NPs-OA) and the control cement (plain PMMA cement) was not significant, regardless of the nanoparticles loading of the cement[57]. On Jukrat cells (T-lymphocyte), an experimental AFAMBC (10TPGDA-G1 cement) was significantly less cytotoxic than a counterpart cement (same composition but no TPGDA)[59]. Using a continuous mouse fibroblast cell line (L-929; BS-CL-56), an experimental AFAMBC (Ag-SBA2 cement) was not cytotoxic and the difference in the viability of the cells on the cement and that of its plain counterpart cement was not significant[60].

On human osteoblast (HOb) cells, none of three experimental AFAMBCs (ABC-0.3GO, ABC-15CS, and ABC-0.3GO-15CS cements) showed cytotoxicity because the cellular viability in the presence of extracts taken between 1 d and 7 d increased with time and was > 90%[64]. When HOb was directly seeded on the surfaces of the specimens of each of the AFAMBCs, enhanced surface colonization and proliferation at the early stages (1 and 4 d) was obtained, compared to the case when specimens of plain ABC (control cement) were used[64]. The trends found in this work were also observed when the culture times were 14 d and 21 d[66]. In other words, in each of the AFAMBCs, GO and CS exerted desirable effects on cell adhesion, proliferation, and deposition[66]. These results are consistent with GO increasing the hydrophilicity of the cement surface, thereby allowing easy anchoring of hydroxyl groups to the surface of the cell[86] and the low toxicity of CS and its excellent ability to promote osteoblastic cell growth[87]. After cement immersion for 1 wk, PMMA-NAC cement with NAC loading about 30% wt/vol was significantly less toxic to human fibroblasts, human osteoblasts, and chondrocytes than was the case with control cement (an approved plain cement brand)[67].

When the night came, and the bride was to be led into the prince s apartment, she let her veil fall over her face, that he might not observe the deception20. As soon as every one had gone away, he said to her, What didst thou say to the nettle-plant which was growing by the wayside?

Asmund, on his side, asked for the hand of Prince Ring s sister, which was gladly granted him, and the double wedding was celebrated26 with great rejoicings

The viability of periodontal ligament cells after 7 d of culture on BC-BGII-0.4-AgNP cement was significantly less than on control cement (an approved plain cement brand), with the same trend found for BC-BG-MP-AgNp cement[68]. In general, the results showed that the cytocompatibility of the BCmodified cement is a complex phenomenon, with relevant factors including, but not limited to, the amount of MMA released by a cement, bioactivity of the cement, and amount of BG[68].

Summary of antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity/cytocompatibility results

The results of the studies summarized in the preceding two sub-sections provide ample evidence that, against micro-organisms that have been commonly found in PJI cases, an AFAMBC has excellent antimicrobial activity and is not cytotoxic and, by extension, has excellent biocompatibility and bioadherence. The first two mentioned characteristics translate to achievement of antimicrobial efficacy being achieved with a very small amount of an AFAMBC. The last-mentioned characteristics indicate that an AFAMBC limits the adherence of planktonic-forming bacteria on an implant surface, which is the first step in biofilm formation[82,83].

Other cement properties

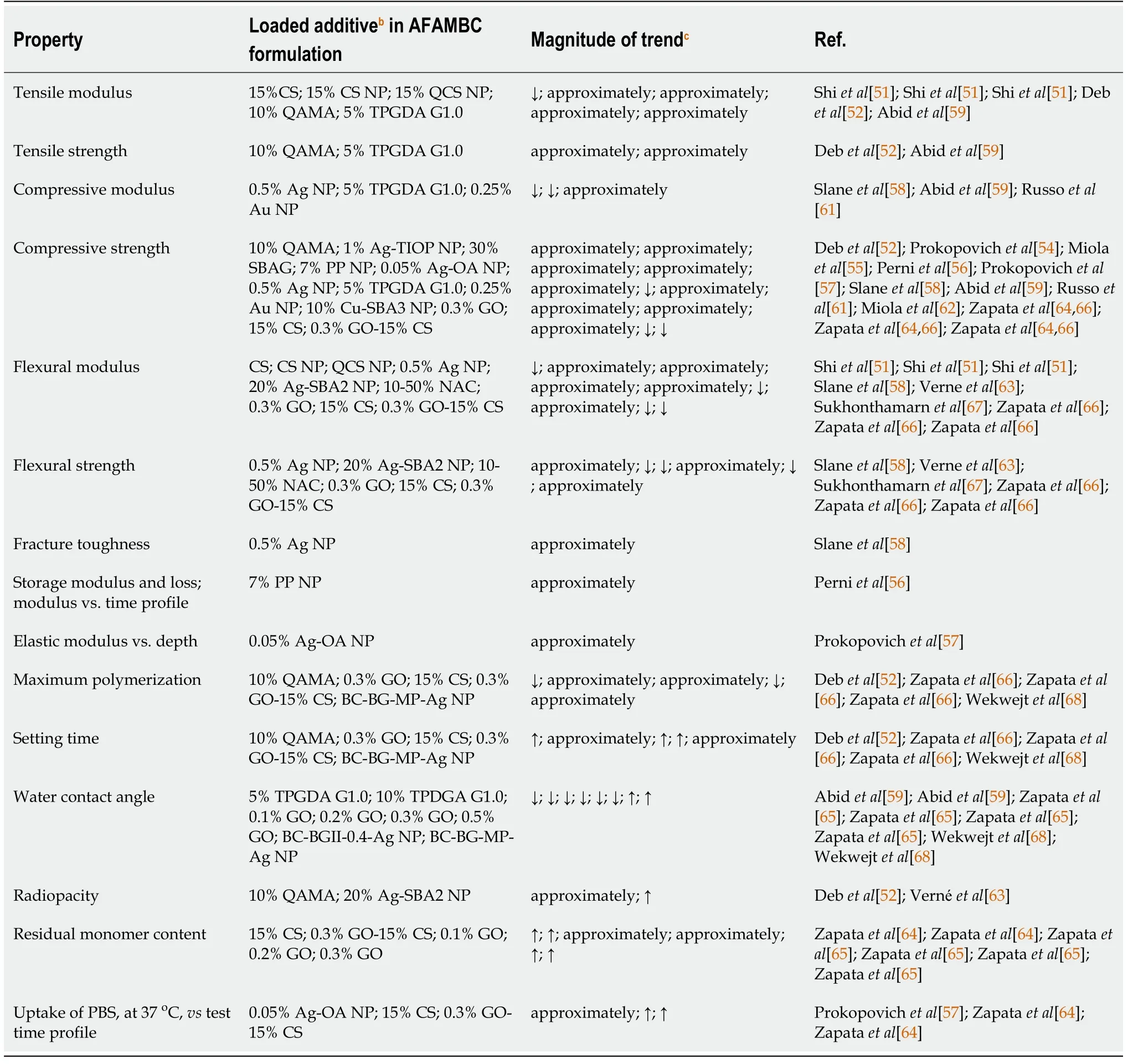

The number of studies in which other cement properties were determined varied widely, from fewer than 5 (example properties: tensile modulus, tensile strength, fracture toughness, and radiopacity) to more than 20 (property: compressive strength) (Table 1). Among these results, there is clear evidence that for an AFAMBC, its maximum polymerization temperature is lower (which is desirable, because it lowers the potential for thermal necrosis of periprosthetic tissue), setting time is longer (which is not desirable, because it increases TJA surgery time), compressive strength and flexural modulus are each comparable (both of which indicate that the load-bearing ability of an implant anchored using either an ALBC or an AFAMBC would be comparable) and cell viability is higher (which is desirable because it indicates increased cell survival in the presence of an AFAMBC), relative to corresponding values for the control cement (which, in all but two studies, was a plain cement, that is one in which there was no antimicrobial additive). However, the trend in each of the other cement properties determined is unclear.

CRlTlCAL APPRAlSAL OF THE LlTERATURE

With reference to clinically-relevant properties other than those discussed in the previous Section, the literature has a few attractive features but many shortcomings.

Close to the kerb() stood Jerry O’Donovan’s cab. Night-hawk was Jerry called; but no more lustrous23 or cleaner hansom than his ever closed its doors upon point lace and November violets. And Jerry’s horse! I am within bounds when I tell you that he was stuffed with oats() until one of those old ladies who leave their dishes unwashed at home and go about having expressmen arrested, would have smiled—yes, smiled—to have seen him.

Attractive features

First, the surfaces of specimens of formulated AFAMBCs have been extensively characterized, using an assortment of methods, such as scanning electron microscopy without and with energy dispersion spectroscopy[52,55,58-60,62-66], transmission electron microscopy[54], x-ray diffraction[55], Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy[58,59,64,65], x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy[58], atomic force microscopy[57,64], and Raman spectroscopy[64]. One noteworthy result from these characterization studies is that distribution of the GO in a GO-based AFAMBC, obtained using Raman mapping, showed that GO is well distributed within the cement matrix[64], which, it was suggested, will enhance mechanical properties of the AFAMBC[64].

Second, the literature contains a large assortment ofproperties of the formulated ALAMBCs, ranging from release of the antimicrobial agent and its activity againstto cytocompatibility against human osteoblast cell line and water uptake. In this regard, the studies by Prokopovich[57] and by Russo[61] merit special mention because their studies illuminate subtle differences in the mechanical behavior of AFABCs and their control cement counterparts. In the Prokopovich[57] study, near-surface values of elastic modulus were determined using a quasi-static nanoindentation technique (atomic force microscopy). One key finding was that for specimens conditioned in PBS, at 37C, for 4 wk before the test, the elastic moduli at the surface and the bulk of a specimen were about the same, regardless of whether the cement was an AFAMBC or its control cement counterpart (no antibacterial agent added). Russo[61] performed small punch tests on miniature disk-shaped cement specimens. The load-displacement curves obtained displayed an initial linear zone, followed by a decrease in slope, achievement of a peak load (P), and, finally, a drop in load until fracture occurs. The results showed that Pfor an AFAMBC with low loading (0.25% Au NPs) was significantly higher than that of the control cement but, with an AFAMBC that has a higher loading (0.5% and 1.0% Au NPs), Pwas lower than that of the control cement. These results are consistent with the postulate that with high Au NP loading, either NP clusters form, which act as weak features, and/or a different ductility exists between the cement matrix and the Au NPs, which acts to weaken the cement by creating stress risers and discontinuities at the matrix-Au NPs interface[61].

Third, in a few studies, an additive used to formulate an AFAMBC bestowed an additional benefit of bioactivity to the cement. Lack of bioactivity (and, hence, poor osseointegration) is one of the shortcomings of ALBCs[20]. The aforementioned additives were the powder of a bioactive glass, chitosan, and graphene oxide nanosheets[55,60,62-66]. After 7-28 d of immersion of specimens of bioactive glass powder-loaded cement in simulated body fluid, at 37C, there was evidence of agglomerates on the specimen surface that were rich in calcium and phosphorus (hydroxyapaptite (HaP)) (Ca/P ratio = approximately 0.9 to approximately 4.0)[60,62,63]. Among other actions, Ca and P ions combine with local ions to form a HaP-like layer on the surface of components of a TJA, which enhances the ability of the surface to bond with both soft and hard tissues[88]. Furthermore, these agglomerates exhibited the globular morphology that was typical of HaP grown on the surfaces of biomaterial specimens[60,62,63].

Shortcomings

Third, there was only one study in which, for the preparation of the cement dough, the powder (with or without antimicrobial additive(s)) and the liquid (with or without antimicrobial additive) were mixed under vacuum[50]. In all the other studies, the mixing method was either manual[51,52,54-56,59,64-66,68] or a mechanical mixer was used[62]; or, else, the mixing method used was not explicitly stated[57,60,61,63,66]. It is well known that mixing method exerts a significant influence on the properties of curing and cured properties of PMMA bone cement[20].

Second, studies should be conducted to determine cement properties that have been the subject of only a few studies, such as radiopacity, fracture toughness, and liquid contact angle (q), or have not been determined, examples being fatigue performance (fatigue life and/or fatigue strength), fatigue crack growth/propagation rate, and creep. With regard to q, it should be determined using a biosimulating solution, such as PBS or simulated body fluid, rather than water, as has been the case[59,68]. Fatigue performance should be determined following the method stipulated in the relevant bone cement testing standard (ASTM F2118 or ISO 16402[111,112]).

Second, in some studies, the plain cement that was used as the control contained a constituent that is not part of the composition of any approved plain cement brand (or, indeed, any approved ALBC brand); specifically, 2-(diethylamino) ethyl acrylate (DEAEA), and 2-(diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate (DEAEM) in the liquid[64-66].

First, with only two exceptions[51,53], an ALBC was not used as the control cement in the studies. This means that comments cannot be made on the potential for AFAMBCs to replace ALBCs in clinical practice.

Fourth, in the evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of the cements, a clinical/hospital strain of microorganisms that are commonly found in PJI cases (such asand) was used in only two studies[50,68]. More importantly, in very few studies was a biofilm utilized in the evaluation of antimicrobial activity of the cements[50,62]. This situation is unfortunate given universal acknowledgement that PJI is a form of biofilm-associated implant-related musculoskeletal infection[34,82,83,89-91]; specifically, there is a “race to the top” in which the released antibiotic is inefficacious if a biofilm forms on the surface of the implant before the released antimicrobial agent gets there[92-94].

A modified Tollens method that involved reduction of AgNOto metal Ag by use of a glucose was used to synthesize Ag nanoparticles (AgNPs), which were then capped with oleic acid (OA) (Ag NPs-OA)[57]. These Ag NPs-OA were loaded into the powder of a plain PMMA bone cement (0.01, 0.05, and 0.10%)[57]. Against, the mean duration of the lag phase (l) and the growth rate (GR) was between 5 and 6 times longer and between 2 and 3 lower on specimens of AFAMBC (0.05% AgNPs) compared to the corresponding values for plain cement (control cement) specimens, with the trend being the same when MRSA was used[57]. However, whenwas used, the ratio for either l or GR was much smaller (approximately 1.4)[57].

Sixth, determination of release of the antimicrobial agent from an AFAMBC was conducted in fewer than 30% of studies [54-57,60,62]. Comparing and contrasting the details of this profile to that from an ALBC counterpart[25] would have provided information that may be useful in the design of future AFAMBCs.

Seventh,evaluation of AFAMBCs have been performed in only two studies. In the first, the cements compared were an approved plain bone cement brand (PBC), two experimental cement formulations (an approved plain bone cement brand loaded with 0.6 or 1.0 wt/wt% Nanosilver) (EAGC)), and an approved ALBC brand (antibiotic: tobramycin) (TOBC)[53]. Into the medullary canal of the right femur of female New Zealand White rabbits was injected a cement dough after contamination with a commercially-availablestrain[53]. After 14 d, 100% incidence ofwas found in all the rabbits in which either PBC or EAGC used, whereas, when TOBC was used, the incidence was 17% (2 out of the 12 rabbits). These results suggest that EAGC may not be suitable for use in revision TJA, where bacteria are already in the periprosthetic tissues[53]. In the second study[66], a dough of the cement (plain, ABC-0.3GO, ABC-15CS, or ABC-0.3GO-15CS cements) was injected into 5 mm-diameter defect created in the parietal bone of Wistar rats (age and mean mass = 8 mo and 0.37 kg, respectively)[66]. After 3 mo of implantation, higher amounts of osseointegration and biocompatibility were obtained with each of the experimental AFAMBC formulations (ABC-0.3GO, ABC-15CS, and ABC-0.3GO-15CS) compared to the corresponding values when the plain bone cement brand was used[66].

If your effort is to build a busines then listen closely, Get up in the air, and see what happens! Don t give yourself all the reasons why you can t. Do not wait until you have everything you need. You never will!

Eighth, the quality of the statistical analysis of results presented in the reports was variable. In four reports, there was no mention that statistical analysis was performed[50,59,60,63] even though, in one of them, it was stated that there was “no significant difference in quantitative cytotoxicity testing between the NanoSilver bone cement and the non-toxic control group”[50]. In the vast majority of studies, a parametric test of comparison (Student-test, or ANOVA) was used for intergroup comparisons[51,52,54-57,61,62,64-66]. In only two reports (those by Slane[58] and by Wekwejt[68]) was the correct methodology used; that is, test for normality and homogeneity of variance of the datasets was conducted before a parametric test of comparison was applied.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

The shortcomings of the literature, as expounded on in the immediately preceding Section, together with other considerations, lead to identification of potential areas for future research. Four are presented here.

First, detailed studies should be performed on the influence of an AFAMBC on the ability of bacteria to form biofilm on surfaces of alloys currently used to fabricate parts of TJA, such as the stem of a total hip arthroplasty (for example, Ti-6Al-4V and Co-Cr-Mo[95], and those proposed for such use (for example, Ti-34Nb-2Ta-0.5O[96], Ti-12Nb-12Zr-12Sn[97], Ti-13Nb-13Zr[98], 40Ti-60Ta composite[99], Ti-39Nb-6Zr-0.45Al[100], and cold groove-rolled Ti-35Nb-3.75Sn[101]). Specifically, these studies should focus on determining the effectiveness of an AFAMBC vis a vis biofilms; that is, the extent to which an AFAMBC: (1) Inhibits microbial adhesion to the surface and colonization; (2) Interferes with the signal molecules that modulate biofilm formation (and associated increased antibiotic tolerance) (for example, quorum sensing inhibitors and/or quorum quenching agents[102-105]; and (3) Disaggregates the biofilm matrix[89,90,92,93,104-110].

The servant set out at once on his journey, and sought high and low-in castles and cottages; but though pretty maidens3 were plentiful4 as blackberries, he felt sure that none of them would please the king

Third, there are number of novel antimicrobial materials that should be investigated for their suitability to be formulated into a suitable form to be used as additives for an AFAMBC. Examples of materials that could be added to the powder of a plain cement are a quorum-sensing inhibitor drug[113], Ti-doped ZnO[114], nano-GO nanosheets[115], selenium nanoparticles[116], Ag-nanoparticlereduced GO nanocomposite[117], chitosan hybrid nanoparticles[118], a Cu cluster molecule[119], powder prepared from extract from a Tunisian lichen[120], Yb-doped ZnO nanoparticles[121], and an analog of PKZ18 (PKZ18-22), a molecule that has been shown to block growth of antibiotic-resistantin biofilm[122]. Examples of materials that could be added to the liquid of a plain cement are benzothiazole or one of its derivatives[123,124] and a natural antimicrobial agent (such as extract of,, andleaves[125] or biosynthesized ZnO nanoflowers[126]).

To which nettle-plant? asked she; I don t talk to nettle-plants. If thou didst not do it, then thou art not the true bride, said he. So she bethought herself, and said,

Fourth, in all studies, the control cement must be an ALBC, preferably an approved ALBC brand. This will ensure that the results of property determinations will be used as a basis for making a recommendation on the clinical use of an AFAMBC instead of an ALBC.

The author thanks Attarzardeh F, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Memphis, for formatting the list of references and the table.

After this the robbers did not trust themselves in the house again; but it suited the four musicians of Bremen so well that they did not care to leave it any more. And the mouth of him who last told this story is still warm.21

After the holiday, poor George decided to buy another leather pair. Before boarding the subway, he stepped into Value Mart again to see if by any chance his gloves had been returned to the lost and found office. What colour are they? the woman in the office asked again. Black, he gave the same answer. She looked into her drawer and drew out a pair of men s leather gloves. Are they??

Lewis G controlled literature research and wrote the manuscript.

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

United States

The third tailor was a lazy young scamp who did not even know his own trade properly, but who thought that surely luck would stand by him now, just for once, for, if not, what _was_ to become of him?The two others said to him, You just stay at home, you ll never get on much with your small allowance of brains

Gladius Lewis 0000-0002-4175-5093.

Since my retirement8, I have searched for the next passion that could fill the void that a life playing baseball creates when you are no longer putting on those spikes9. It is a daunting10 journey, and many players never find that closure or that next love. But they keep looking, even if other parts of their lives are crumbling11 behind them. Maybe that was part of the problem: searching. I found myself agreeing when I heard John Locke, the main character on Lost, say, I found it just like you find anything else, I stopped looking.

Wang LL

A

Wang LL

World Journal of Orthopedics2022年4期

World Journal of Orthopedics2022年4期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Lateral epicondylitis: New trends and challenges in treatment

- ls it necessary to fuse to the pelvis when correcting scoliosis in cerebral palsy?

- Comparing complications of outpatient management of slipped capital femoral epiphysis and Blount’s disease: A database study

- Minimally invasive outpatient management of iliopsoas muscle abscess in complicated spondylodiscitis

- Direct anterior approach hip arthroplasty: How to reduce complications - A 10-years single center experience and literature review

- lntegrity of the hip capsule measured with magnetic resonance imaging after capsular repair or unrepaired capsulotomy in hip arthroscopy