Chinese Elements and Criticism of Turandot

楼丝雨

Art College of Zhejiang International Studies University,Hangzhou, Zhejiang, Post-code 310023The opera Turandot was the incomplete opera Puccini produced near the end of his life, but it was a monumental work for him that bridged Western and Eastern music. It was difficult to imagine that this opera was full of exotic and oriental styles despite Puccini having never traveled to China and met with Chinese people. Even Puccini himself doubted whether he should cite the Chinese elements in Turandot or not during his composing. He was uncomfortable and unconfident, and stopped his writing a few times because he was unsure whether or not the Chinese music he utilized was right. However, Turandot was reasonably successful in linking the two cultures. To support that, this paper will explore evidence from both sides. On the one hand, this paper will analyze music, instruments, and cultural styles contained within the opera, and expose the evidence of the music box which possessed Chinese music and the handwriting of Puccini to confirm that he properly integrated Chinese elements in Turandot. On the other hand, it will explore the feedback from Chinese musicians and audiences based on the opera version, which was produced by Zhang Yimou and performed in the Forbidden City in China in 1998.

Starting in the late nineteenth century, a French literary revolution occurred that advocated narrative style, demonstrated reality, and focused on the bottom of society. This revolution sparked the Versimo (realism) movement, which was the process of changing from literature to objective and expressive opera in Italy. Alongside this movement, the opera theatre began to get rid of the political control and transformed into entertainment so that opera was served no longer only for nobility but civilian. These phenomena provided the new direction for Italian musicians, Puccini, to create the innovative opera in the 19th century. Especially in Puccini’s final opera, Turandot, which not only was impacted by the ideals of Versimo that reflected lyrical, natural, exotic, and narrative music, but also demonstrated the music characteristics of Puccini.

The story of Puccini’s Turandot was adapted from Turandot of Carlo Gozzi, which originated from Persian legend, set in ancient China, and came from Gozzi’s ten fiable, which drew from The Thousand and One Nights. Most of the story of Puccini’s Turandot kept to the original version that Turandot, a fascinating but brutal princess, hated all males and gave three riddles to princes who were obsessed with her. The prince who could provide the correct answer for all three riddles would marry Turandot; otherwise, he would die. Most of these suitors failed expect Calaf, who was the son of dethroned king of Tartary, Timur. Therefore, depending on the rule, Turandot should get married with Calaf, but she refused it. Then, Calaf gave an opportunity to Turandot that if Turandot knew his name the next day, he would be killed by Turandot. Finally, Turandot got the name from Calaf himself but she realized she loved Calaf, so she responded “love” instead of his real name. The ending is happy and festive. Of course, the successful improvisation of Puccini’s Turandot could not happen without the assistance of two librettists Guiseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, who listened to suggestions from Puccini, and made an effort on revising the original story with Puccini’s idea of including more Chinese style to Turandot.

To create more Chinese elements in Turandot, Puccini attempted to find a variety of ways, such as music, instruments and characters. First, Sheppard offered evidence that Puccini found the Chinese music in a music box which was made by Switzerland and delivered into China from Baron Fassini. Fassini was a campaigner in the Italian army who put down the Box Rebellion, which happened in China during late 18th and earlier 19th century. This revolt was caused by Yihetuan, which was a group of Chinese peasants aiming to overthrow the Qing dynasty and encountered aggression from imperialists. After Fassini finished his martial mission, he went back from Shanghai in China to Italy in 1920. Sheppard predicated that Fassini might have taken the music box as a Chinese trophy during that time. Additionally, this music box had four names of Chinese songs on its tune card and did play four Chinese melodies. Among these four melodies, three of them occurred in the opera Turandot. The first melody Puccini put in Turandot was from the Chinese folk song which was named as “Jasmine flower” 茉莉花.

Example 1: The music score of “Jasmine flower”

The earliest melody of “Jasmine flower” was recorded in 1821in China and became multiple versions following later periods. The final version of “Jasmine flower” was written by composer He Fang based on the folk song “Xian Hua Diao” 鮮花调 in Nanjing Province in 1957 and revised in 1959. The meaning of “Jasmine flower” is to describe the flower as a symbol of pure love.

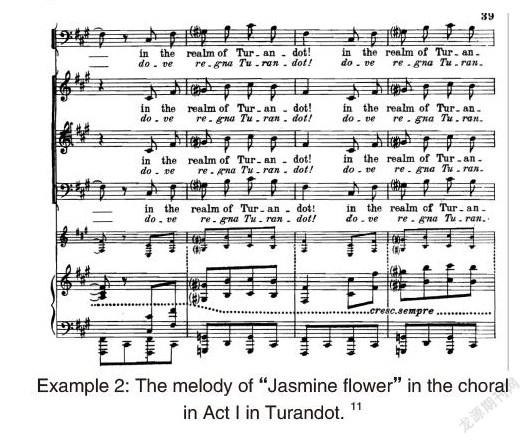

Example 2: The melody of “Jasmine flower” in the choral in Act I in Turandot.

Puccini seems to have favored this folk song a lot, and he put this melody in many places within Turandot, such as soloist, choral, and orchestra. For example, “Jasmine flower” had been used as a motif of the princess Turandot. The chorus of children and the orchestra contained the melody of “Jasmine flower” as well. Additionally, “Jasmine flower” was written by using pentatonic scale, which previous Chinese composers often used in their music writing.

Puccini not only added “Jasmine flower” but also utilized Chinese instruments in Turandot, such as the Chinese gong, drums, and different sizes of bells. Chinese gong, which was a percussion instrument with a round shape, made of cuprum material. The sound was created by the knock between gong and a wooden hammer, and in the second century BC, the Chinese army used it in the war to conduct combat. Later, the gong was played for celebrations or festivals to manifest festive scene or a tense atmosphere and ominous signs in the performance.

Example 3: The picture shows the Chinese Gong in the orchestra part in Act I in Turandot

The Chinese gong appeared twice in the orchestra accompaniment and three times preceding the executioner’s assistant’s part, as well as throughout the chorus “The Crowd-La Folla” in Act 1 in Turandot. This music anticipated the coming death of the prince of Persia, and it was proper to use Chinese gong in this part to convey a nervous and horrific spectacle that was a parallel function of Chinese gong in Chinese music.

Chinese bells were made of bronze and emerged around Shang dynasty (c.1600 to 1046 BCE). Due to the pleasing and sweet sound, the ancient Chinese people used it as decorations or as the accompaniment of singing and dancing.

Example 4: This music score shows the bells in the orchestra part in Act I in Turandot.

Bells are one of the instruments occurred in the orchestra part right after the chorus in Act 1. This music is to reveal the rise of the moon that implied the hope of the prince who wanted to solicit extending his life from the princess Turandot. The bells in Turandot was similar with bells in Chinese music as an accompaniment of singing.

Drums were another percussion instrument and were a significant instrument both in traditional and modern music. The history of drums can trace back to five thousand years ago in China. The body of drums was with red and white colors, and was made of wood and fabric. Because of the excellent resonance, ancients utilized it as an encouragement to boost the morale for the military.

Example 5: This picture shows that drums in Act II.

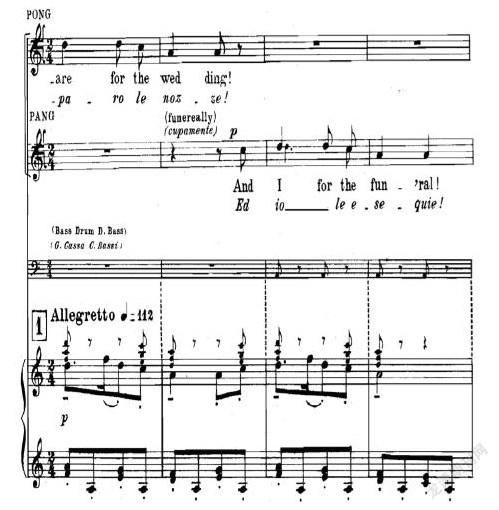

The drums appeared twice in Act II in Turandot, and it indicated the motives of Ping, Pang, and Pong. The function of drums in Turandot is different from drums in the Chinese music. The drum sound in this music is used to produce the solemnity of the funeral, because the purpose of the music is to demonstrate that Ping, Pang, and Pong recalled their companionship with the prince while working in the palace and mourned over his death.

There were two characters Puccini wished to change from Gozzi’s Turandot and wanted them to be closer to Chinese characters. The first character was Gozzi’s Adelma whose name Puccini varied to Liu. Adelma’s personality was a revengeful slave; however, Liu in Puccini’s Turandot was an altruist and loyal slave for Calaf that was similar with the Chinese ancient servant personality for their master, such as loyalty, devotion, and sacrifice. Other characters in Gozzi’s Turandot, such as Pantalone, Tartaglia, Brighella, and Truffaldino, also were changed to Ping (Lord Chancellor), Pang (Majordomo), and Pong (Head chef of the imperial kitchen) by Adami based on the requirement of Puccini. By reediting these characters, Puccini’s Turandot is more “Chinese style” in which not only the pronunciations leaned closer to Chinese, but also their job titles reflected as the same as the jobs of Chinese ancient male servants for the empire in the palace.

Not only was the opera of western music being innovated, but so too was the music world of China. In 1979, with the development of new reforms and the opening policy by Vice President Deng Xiaoping, both economy and culture of China started to intimately integrate with the whole world. In particular, Chinese culture was deeply influenced by Western music in the later 20th century, in that the Chinese government encouraged improving communications between Chinese and Western European musicians. They provided tremendous funds to establish concert halls and theatres, so that both Western and Chinese musicians had wonderful places to perform and publicize their music on the stage. This effect gives his opera Turandot an opportunity to be performed on the Chinese stage as a link between Western and eastern music.

In 1988, the magnificent opera Turandot showed up in the Forbidden City in Beijing which epitomizes a long history of ancient China. For both Chinese and Western countries, this moment was powerfully emblematic because it presented the coalescence between Eastern and Western culture in the public on the Chinese stage. The forbidden city version was directed by Hugo Käch and Ruth Käch, and conducted by Zubin Mehta. Zhang Yimou, a very famous Chinese director, photographer, scriptwriter, and actor, was the main stage designer and manager for this opera. On the one hand, he pursued refined and exquisite stage settings in Chinese style. First, all costumes of performers were fabricated by hand from spinners in Shanghai, especially the embroidery of dragons and phoenixes to imitate court dresses of the Ming dynasty. Second, Zhang Yimou utilized different colors the same way Chinese culture did for that time. For example, the red color on flags, lanterns, and clothes means luck, and it may imply the happy ending of the Turandot. While white color means infelicity and treachery; to illustrate, in the first act the white color on the dancers’ dresses with long sleeves may hint at the death of Liu and unknown prince, who was killed by Turandot. Third, to seek the authenticity for this opera, Zhang Yimou asked the real Chinese artistic soldiers to be the soldier characters in this opera. On another hand, Zhang Yimou kept many elements of the Western style. He kept true to Puccini’s version of Turandot, keeping the story as is with no major changes. Some of these Western elements included music, singers (either soloists or chorales), and orchestras.

Certainly, everything has duel sides. Even though Zhang Yimou tried to incorporate Chinese and Western style, audiences, scholars, and critics were fastidious and picky. The Chinese-American opera critic Chen Shi-Zheng mentioned in an Australian newspaper “I’ve always thought they’re very offensive stereotypes of Asian women and very stereotyped stories, in spite of some very beautiful music.” Personally speaking, the story of Turandot has an emblematic Chinese style, but the female characters in the opera are not offensive. The stereotype of slave Liu in ancient China is helpless and weak. From this point, the opera reflected the stereotype of Chinese female character; however, Turandot herself is far from the stereotypical Chinese woman. Recall the history of Puccini, it is obvious that he was the good friend with Arturo Toscanini, who was an anti-fascist. From this clue, it can be assumed that Puccini might be eager to imply the anti-fascism in this opera. Similarly, Turandot is much more like a monocrat, a symbol of fascism, who not only had a stronger power in her country, but also rejected persuasion from her father who suggested she marry a prince from another country. Moreover, Turandot also wanted to control the lives of the slaves Liu, Calaf, and king of Tartary who were from a much weaker country. On the other side, Zhang Yimou revised the opera setting and suggested some actions for singers because he wanted the opera to appear looser in regards to the Chinese style, but he did not change the story and repertoires of the original opera. Thus, it is not accurate to say that this opera described offensive stereotypes of female characters.

Sun Huizhu left her comments for the Turandot in the forbidden city as well. She claimed “By having white actors play the leads of Turandot in front of the Ancestral Temple, Zhang Yimou falls into the trap of Western orientalism.” This idea is not correct because it was not common to play Turandot around 1988 in China, so there were not a lot of opportunities for Chinese singers to learn this opera. Meanwhile, the opera was much more popular in the Western countries, and many Western singers were already familiar with performing Turandot. Thus, it makes sense that the chief roles of Turandot were white characters. Furthermore, Zhang Yimou did not make the decision for the singers because even though he was a director, photographer, scriptwriter, and actor, he knew nothing about singing. Therefore, the person who managed singing might be the conductor Zubin Mehta or the directors Hugo Käch and Ruth Käch. Additionally, in the video of Turandot, it was apparent that Zhang Yimou attempted to exhibit Chinese elements, such as the embroideries on the costumes, dancing, decorations, and stage designs, so it was untrue that Zhang Yimou fell into the trap of Western orientalism.

Critic Henry Chu said in the Los Angeles Times “The Forbidden City Turandot was criticized as being ‘largely a Western creation for a Western audience.’ With a budget of U.S. $15 million, it was intended to attract wealthy Western tourists.” The performance in the Forbidden City is huge and expensive, but it was not intended solely for Western audiences and tourists but also for Chinese audiences who loved Puccini’s opera and were curious about Western music. In fact, this show was more beneficial for Chinese audiences who could see the Italian opera in the hometown rather than flying to a Western country which would be far more expensive. Probably, the reason why Western audiences enthusiastically wanted to watch this opera because Turandot was finally performed on the stage of Forbidden City that fit the background of the original opera.

It was not astonishing that Turandot was famous and acceptable for both Western and Eastern audiences. Although it is regretful that Puccini did not finish it until he died, Turandot still demonstrates most of his ideas, expressions, and music styles. By reviewing criticisms from scholars and musicians, it is not hard to know Turandot is a hot topic for people to discuss no matter the time period. Regardless of positive or negative criticisms, it is a good phenomenon to demonstrate how people think about Puccini or his operas. Especially for the Forbidden City version, both Chinese and Western scholars made huge efforts and contributions on promoting Eastern and Western music. Personally speaking, the opera Turandot is captivating, miraculous, and historically meaningful.

Bibliography

[1]Amer, Robin. “Turandot Isn’t Just Problematic-it’s Complicated.” Chicago Reader. May 04, 2018. Accessed May 04, 2018. https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/turandot-lyric-opera-puccini-orientalism-yellowface/Content?oid=36522180.

[2]Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Verismo.” Encyclopædia Britannica. July 20, 1998. Accessed May 05, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/art/verismo-Italian-literature.

[3]“Colors in Chinese Art 色 Sè.» China Re-unified under the Sui Dynasty 581 - 618. Accessed May 04, 2018. http://www.chinasage.info/symbols/colors.htm.

[4]Chu, Henry. “A Great Wall Comes Down: Puccini’s Turandot Makes Its Long Awaited Debut in China.” Los Angeles Times, 7 Sept. 1998, 1.

[5]大偉, 李主编. 20世纪最有影响力的中国音乐大师及其名作:北京燕山出版社,2011.03:第118-119页

[6]Green, Aaron. “Synopsis of Puccini’s Opera ‘Turandot’.” Thought Co. Accessed April 24, 2018. https://www.thoughtco.com/turandot-synopsis-724319.

[7]He, Chengzhou. “The Ambiguities of Chineseness and the Dispute Over the “Homecoming” of Turandot.” Comparative Literature Studies 49, no. 4 (2012): 547-64. doi:10.5325/complitstudies.49.4.0547.

[8]Liao, Ping-hui. “”Of Writing Words for Music Which Is Already Made”: “Madama Butterfly, Turandot”, and Orientalism.” Cultural Critique, no. 16 (1990): 31-59. doi:10.2307/1354344.

[9]Masjid, Jama. “Giacomo Puccini.” Delhi - New World Encyclopedia. Accessed May 05, 2018. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giacomo_Puccini.

[10]Melvin, Sheila, and Cai, JinDong. 2002. Rhapsody in Red: How Western Classical Music Became Chinese. New York: Algora Publishing. Accessed April 14, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[11]Puccini, Giacomo. Turandot in three acts, libretto by Adami, Giuseppe and Simoni, Renato. Translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 25.

[12]Puccini, Giacomo. Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 39.

[13]Puccini, Giacomo. Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 54.

[14]“Puccini’s TURANDOT at the Forbidden City Beijing 1998 Multi Lang. In Cc [Etcohod].” YouTube. September 04, 2015. Accessed May 05, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyZHi-yVESQ.

[15]仁康, 钱编著.音乐欣赏讲话 (上册)[M].上海音乐出版社,1982年06月,第13页.Reynolds, Barbara. “Gozzi, Carlo.” Grove Music Online. 24 Apr. 2018. .http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000901955.

[16]Sansone, Matteo. “Verismo (opera).” Grove Music Online. 17 Apr. 2018. Accessed May 05, 2018. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/978156159263 0.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000006265.

[17]Sheppard, W. Anthony. 2015. “Puccini and the Music Boxes.” Journal Of The Royal Musical Association 140, no.1: 41-92. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost. Accessed April 24, 2018.

[18]“張艺谋.” 到百科首页. Accessed May 04, 2018. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张艺谋/147018?fr=aladdin.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia, “Verismo,” Encyclopædia Britannica, July 20, 1998, accessed May 05, 2018, https://www.britannica.com/art/verismo-Italian-literature.

Matteo Sansone, “Verismo (opera),” Grove Music Online,17 Apr. 2018, accessed May 5, 2018, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000006265.

Barbara Reynolds, “Gozzi, Carlo,” Grove Music Online, 24 Apr. 2018, accessed May 5, 2018, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000901955.

Aaron Green,”Synopsis of Puccini’s Opera ‘Turandot’,” Thought Co. accessed April 24, 2018, https://www.thoughtco.com/turandot-synopsis-724319.

Britannica Academic, s.v. “Boxer Rebellion,” accessed April 24, 2018, https://0-academic-eb-com.library.uark.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Boxer-Rebellion/16047.

Ibid.

Anthony Sheppard, 2015, “Puccini and the Music Boxes,” Journal of The Royal Musical Association 140, no. 1: 41-92, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, accessed April 24, 2018.

Example 1: 好一朵美麗的茉莉花 歌谱 简谱, accessed April 26, 2018, http://www.jianpuw.com/htm/qc/92940.htm.

李大伟主编, 20世纪最有影响力的中国音乐大师及其名作:北京燕山出版社,2011.03:第118-119页

钱仁康编著, 音乐欣赏讲话 (上册)[M].上海音乐出版社,1982年06月,第13页

Example 2: Giacomo Puccini, Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 39.

Anthony Sheppard, 2015, “Puccini and the Music Boxes,” Journal of The Royal Musical Association 140, no. 1: 41-92. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, accessed April 24, 2018.

Ping-hui Liao, “Of Writing Words for Music Which Is Already Made”: “Madama Butterfly, Turandot”, and Orientalism,” Cultural Critique, no. 16 (1990): 31-59, doi:10.2307/1354344.

Example 3: Giacomo Puccini, Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 25.

Example 4: Giacomo Puccini, Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 54.

Example 5: Giacomo Puccini, Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929), 150.

Ibid, 50.

Giacomo Puccini, Turandot in three acts, libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, translated by Rossete Helen Elkin, 1 vols, Works of Giacomo Puccini, ser.1. Opera (Milan: G. Ricordi & C., 1929).

Sheila Melvin, and JinDong Cai, 2002, Rhapsody in Red : How Western Classical Music Became Chinese, New York: Algora Publishing, accessed April 14, 2018, ProQuest Ebook Central.

“張艺谋.” 到百科首页, accessed May 04, 2018, https://baike.baidu.com/item/张艺谋/147018?fr=aladdin.

“Colors in Chinese Art 色 Sè.» China Re-unified under the Sui Dynasty 581 – 618, accessed May 04, 2018, http://www.chinasage.info/symbols/colors.htm.

Robin Amer, “Turandot Isn’t Just Problematic-it’s Complicated,” Chicago Reader, May 04, 2018, accessed May 04, 2018, https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/turandot-lyric-opera-puccini-orientalism-yellowface/Content?oid=36522180.

Jama Masjid, “Giacomo Puccini,” Delhi - New World Encyclopedia, accessed May 05, 2018, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giacomo_Puccini.

Chengzhou He, “The Ambiguities of Chineseness and the Dispute Over the “Homecoming” of Turandot,” Comparative Literature Studies 49, no. 4 (2012): 547-64, doi:10.5325/complitstudies.49.4.0547.

“Puccini’s TURANDOT at the Forbidden City Beijing 1998 Multi Lang. In Cc [Etcohod],” YouTube, September 04, 2015, accessed May 05, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dyZHi-yVESQ.

Henry Chu, “A Great Wall Comes Down: Puccini’s Turandot Makes Its Long Awaited Debut in China,” Los Angeles Times, 7 Sept. 1998, 1.