Gut and liver involvement in pediatric hematolymphoid malignancies

lNTRODUCTlON

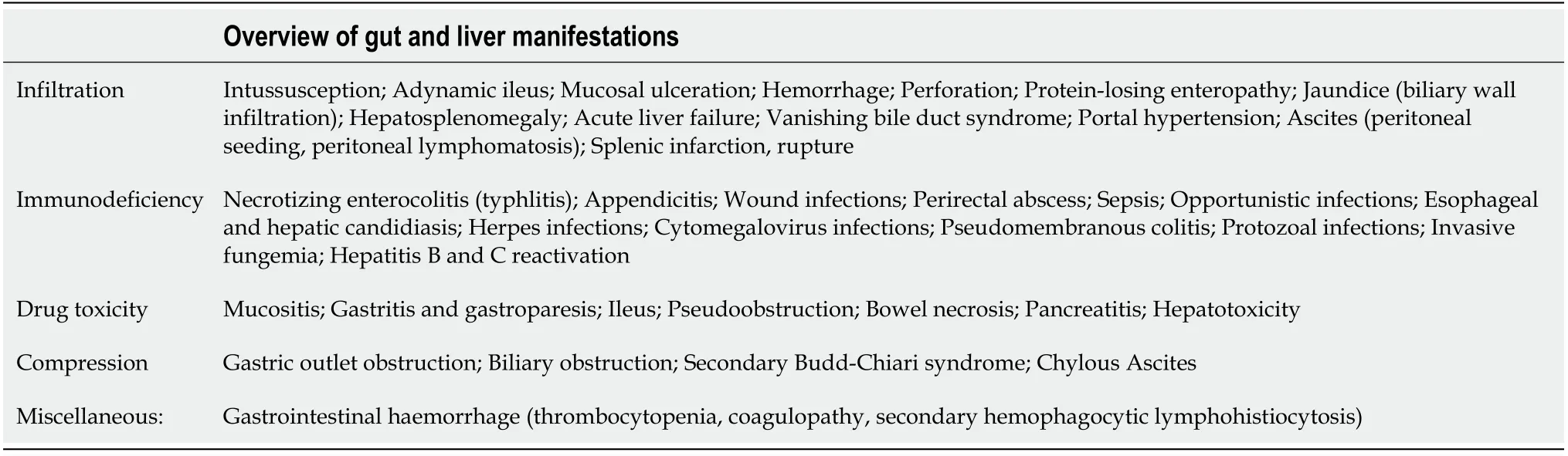

Hematolymphoid malignancies in children are characterized by uncontrolled clonal proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells with resultant infiltration of bone marrow and involvement of lymphoreticular system including lymph nodes,Waldeyer’s ring,thymus,liver,spleen and gut.Their diverse complications are seen mainly in the abdomen which is often challenging for a pediatric gastroenterologist(Table 1).The liver is a part of the reticuloendothelial system and is hence invariably involved.Hematologic malignancies disseminate to infiltrate vital organs such as the gastrointestinal(GI)tract and pancreas.Nodal compressions and drug toxicities can often involve the pancreatobiliary system.Rarely the peritoneum is also infiltrated and complicates the clinical scenario.As the systemic complaints overwhelm the clinical picture,the abdominal manifestations are undermined and underreported leading to a lack of robust data in children.This review collates the majority of the available literature and sheds light on their diverse abdominal manifestations which range from asymptomatic involvement to life-threatening conditions.This review is limited to the discussion of the important hematolymphoid malignancies such as leukemias,lymphomas,and Langerhans cell histiocytosis(LCH).Discussion on detailed chemotherapeutic management and various opportunistic infectious complications of hematolymphoid malignancies affecting the abdomen are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Rationale of the review

The gut and liver involvement in hematolymphoid malignancies frequently manifests with features that overlap with chronic infections and inflammatory conditions.The review may help readers in tackling the common clinical dilemmas and give a clear outline of various abdominal complications encountered in hematolymphoid malignancies.This may in turn improvise interdisciplinary referrals between a hematologist and pediatric gastroenterologist during the management for better outcomes.

LEUKEMlAS lN CHlLDREN

The acute leukemias of childhood collectively represent about 32% of malignancies in children younger than 15 years of age[1].Of all the leukemias in childhood,97% are due to acute leukemias constituting lymphoid(76%),myeloid(20%),or undifferentiated lineage(1%)variants.Chronic myeloid leukemia(CML)and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia(JMML)constitute the remaining 3%[2].Infiltration of lymphoreticular organs,mainly the spleen,liver,and lymph nodes is a characteristic feature of acute leukemias[3].

Acute lymphoid leukemia

The most common hepatic involvement at initial presentation is asymptomatic hepatomegaly,reported in up to 68% of acute lymphoid leukemia(ALL)pediatric patients.At the initial diagnosis,34%-61% of children have enlargement of the liver or spleen(palpable organomegaly approximately > 4 cm below the costal margin)[1].Abnormal liver biochemistry is seen in two settings of ALL:At initial diagnosis and/or during the treatment course.It is speculated that in ALL,there is a direct portal and sinusoidal infiltration by leukemic cells.The rise in liver transaminases is a consequence of hepatocellular necrosis due to leukemic infiltrates[4].In a study by Segal

[4],elevated liver transaminases were overall found in 34% of patients at presentation.Hepatosplenomegaly on physical examination was noted in 34% with hepatitis

56% of patients without hepatitis(

= 0.014).Additionally,3.4% had conjugated hyperbilirubinemia along with abnormal liver enzymes.There wereno significant differences in the overall outcome among those who had normal

elevated transaminases.Hence it was inferred that hepatitis at the time of diagnosis of ALL does not significantly affect the outcome or the induction chemotherapy success.Liver biopsy is not routinely advocated in ALL patients presenting with hepatitis.Due to concomitant bone marrow depression,these children carry a higher risk for bleeding complications as compared to patients having non-malignant liver disease[5].The usual resolution of hepatitis with treatment suggests that liver biopsies should be reserved in patients with abnormal liver biochemistry who are either refractory to induction chemotherapy or have persistent hepatitis despite normal viral studies and abdominal imaging.The indications and timing of the liver biopsy should be individualized on a case-to-case basis and performed only if necessary.Liver failure as the presentation has been rarely reported in ALL[5].This entity is commonly associated with T-cell ALL and has an overall poor prognosis despite the initiation of chemotherapy or liver transplantation.Anecdotal reports suggest short-term success after liver transplantation[6].Rarely ischemia may be seen in hypovolemic conditions secondary to sepsis or volume loss.Occult chronic hepatitis B or C may reactivate during chemotherapy.Acute and chronic infection of hepatitis B or C may occur due to unscreened blood product transfusion.In countries with a high seroprevalence of cyto-megalo-virus(CMV),hepatic reactivations are often noted during the induction or maintenance phase of chemotherapy with steroids as they impair cellular immunity against CMV.Other systemic viral,bacterial,fungal,or parasitic infections may ensue due to an overall immunocompromised state.

It is observed that the use of steroids during pre-phase induction chemotherapy normalizes the abnormal liver biochemistry in ALL patients presenting with hepatitis without features of fulminant liver failure.This allows full induction chemotherapy to be delivered under the routine protocol.In those with significant liver dysfunction,current ALL induction protocols suggest a dose reduction in chemotherapy agents or withholding a dose[4].On chemotherapy,any rise in liver enzymes merits a thorough workup.They usually reflect liver injury secondary to chemotherapeutic agents such as methotrexate,L-asparaginase,6-mercaptopurine(6-MP),daunorubicin,and vincristine.Persistent elevation of liver enzymes particularly occurring after 6-MP exposure necessitates evaluation for thiopurine methyltransferase activity.Those with abnormally low levels should not be given 6-MP and require either dose modification or replacement with other chemotherapeutic agents[7].High dose methotrexate(> 500 mg/m

),anthracyclines and L-asparaginase can cause liver cell failure in a predisposed patient with underlying liver disease.Genetic polymorphisms of various enzymes are involved in the drug metabolism during the therapy of ALL[8-10].

Pathogenesis of GI involvement is multifactorial.Various hypotheses include leukemic infiltration of gut mucosa,mucosal injury by chemotherapeutic agents(

methotrexate),gut neuropathy(

vincristine),and cancer cachexia.In the latter,there is a reduced anti-oxidant pool to support epithelial regeneration leading to the disrupted mucosal surface,intestinal edema and engorged vessels.These pathophysiologic alterations along with neutropenia and immune dysregulation make the gut more vulnerable to bacterial intramural invasion[11,12].In a study of 273 children with ALL,GI symptoms at initial presentation were abdominal pain(19.5%),abdominal distension(18.5%),vomiting(14.9%)and bleeding(7.9%)[13].In a retrospective analysis of 129 children with ALL who underwent upper GI endoscopy before chemotherapy,overall 82% had features suggestive of GI inflammation.Lesions in the esophagus,stomach,and duodenal bulb were 8.5%,78%,39.5%respectively.Concomitant

infection was also found to be an uncommon cause of gastritis in leukemic children as compared to adults[14].Leukemic infiltrates in the GI tract initially remain clinically silent.Necrotizing enteropathy or typhlitis may occur in terminal stages[2].Typhlitis is more common with acute myeloid leukemia(AML)than ALL(cumulative risk of 28.5%

7.4%respectively)[12].Typhlitis is diagnosed by the presence of a clinical triad of abdominal pain,fever,and neutropenia or imaging signs(thickened bowel wall)[12].Gram-negative rods,gram-positive cocci,enterococci,fungi,and viruses have been implicated as causes[11].Fungal infections can play an important role in necrotizing enteropathy.A systematic review of published case studies found significantly lower mortality rate in patients receiving antifungal agents for the treatment of necrotizing enteropathy[15].In such situations,it may not be often possible to distinguish from other differential diagnoses such as pseudomembranous colitis,appendicitis,or ischemic colitis.Frank or localized intestinal perforation can culminate rapidly.Abdominal plain X-rays may show a dilated atonic cecum and ascending colon filled with liquid or gas,signs of intramural gas,and small bowel dilatation.However,X-rays have limited value due to their poor sensitivity and specificity[16].On contrastenhanced computed tomography(CT),bowel wall thickening is significantly more prominent in

(

)colitis(mean wall thickness,12 mm;range,8-20 mm)than in neutropenic enterocolitis(mean wall thickness,7 mm;range,4-15 mm;

< 0.01)[17].Inflammatory mass,pericolonic inflammation,and pneumatosis intestinalis may be rarely seen[11].A barium enema is contraindicated due to its potential in causing colonic perforation and septicemia.Colonoscopy is best avoided unless biopsies are required to differentiate the condition from

colitis[18].Medical therapy is the mainstay of management.Though most children with typhlitis respond to broad-spectrum antibiotics along with the anaerobic cover,granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support,intensive fluid replacement,and bowel rest,there is still a risk of mortality in 20%[12].Initial empiric coverage for antifungal agents is not routinely recommended but they can be considered if the initial therapy does not show optimal response in 72 h[11].Indications for surgery include bowel perforation,uncontrolled massive GI bleeding,abscess or appendicitis which occurs in 0.5%-1.5% of patients[11,19].

On a background of an already inflamed gastric mucosa,steroids and anthracyclines can predispose to further gastritis.In addition,vincristine used during the induction phase can lead to neuropathy of the GI tract causing gastroparesis,paralytic ileus and colonic atony.Changes in the gut microbial flora,small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and postchemotherapy pro-inflammatory state cumulatively predispose the GI tract to be the source of febrile neutropenia in children with leukemia[20].

Pancreatitis has been rarely reported due to a progressive infiltrative disease or hypercalcemia[21].The natural history of acute pancreatitis in hematolymphoid malignancies is modified due to the immunocompromised state when compared to normal individuals.The systemic inflammatory response syndrome may often be masked and the compensated anti-inflammatory response may occur earlier in the course.Abdominal complications include abdominal compartment syndrome,hemorrhage,infected necrosis,walled-off collections,and bowel obstruction.Endoscopic and radiological interventions in the induction phase may be precluded by thrombocytopenia due to disease or septicemia related.In a recent study,most children with treatment-related pancreatitis had genetic polymorphisms in 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase(ABAT),asparagine synthetase,and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator(CFTR)genes.Notably,these children harboured many more CFTR variants(71.4%)when compared to controls(39.1%).Identifying correlative variants in ethnically vulnerable populations may improve screening to identify which subgroup of patients with ALL are at the greatest risk for pancreatitis[22].

Acute pancreatitis is most commonly described with the use of L-asparaginase in the induction period[13,14].L-asparaginase-associated pancreatitis had an earlier incidence ranging from 0.7% to 24% and mortality rates of 2%-5%[23].Incidence of acute pancreatitis is between 7%-18% in ALL.Due to the high recurrence rates of acute pancreatitis after rechallenge,it is one of the most common causes of truncation of asparaginase therapy during chemotherapy[23].Studies assessing asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in children with ALL retrospectively reported incidences between 6.7% to 18%.Severity can range from mild to severe pancreatitis,which could be influenced by their immune suppression,frequent microbial translocation from the gut,coagulation disturbances,hyperlipidaemia associated with asparaginase-containing combination chemotherapy and the presence of leukemic infiltrations in the pancreas altering micro-architecture with most cases improving by withdrawal of the drug and conservative management[24].Chronic complications rarely occur in the form of chronic pancreatitis or diabetes mellitus[23].Acute pancreatitis has been reported after treatment with all asparaginase formulations[23].A retrospective analysis of 403 children with ALL who developed acute pancreatitis after Peg-asparaginase administration revealed that patients with higher median age(10-18 years)have 2.4 times increased risk of pancreatitis than the younger ones.There was a non-statistically significant trend towards inferior 5-year event-free survival.Also 29% of patients with a known history of acute pancreatitis subsequently relapsed compared to only 14%with no prior history of acute pancreatitis[25].ATF5 362TT and CT genotypes were associated with decreased risk of developing acute pancreatitis and have better disease outcomes demonstrating a low risk for events and superior survival[26].Pancreatitis was more common in asparaginase-containing blocks

non-asparaginase containing blocks(83%

17%;

< 0.0001).The median interval between receiving Peg-asparaginase dose and developing acute pancreatitis was 10 d.In a recent systematic review,older age,asparaginase formulation,higher ALL risk stratification,and higher asparaginase dosing appear to play a limited role in the development of acute pancreatitis.The Ponte di Legno Toxicity Working Group reviewed a large number of trials to investigate the risk of complications and risk of re-exposing patients with acute pancreatitis[27].Complications noted in the 465 patients with acute pancreatitis included mechanical ventilation(8%),pseudocysts(26%),acute insulin need(21%),and death(2%).Older age was associated with more complications(10.5 years

6.1 years without complications;

< 0.0001).One year after diagnosis of acute pancreatitis,11% of patients continued to need insulin,had recurrent abdominal pain,or both.Ninety-six patients were re-exposed to asparaginase,including 59 after severe acute pancreatitis.Forty-four(46%)patients developed a second episode,22(52%)were severe,suggesting a high risk of recurrence[27].Presently most oncologists agree that after recovery from a documented episode of pancreatitis,re-challenge with L-asparaginase should be an absolute contraindication.Re-challenge in mild pancreatitis is fraught with a high risk of recurrence,sometimes more severe than the first episode.Hypertriglyceridemia from L-asparaginase can also predispose to acute pancreatitis.Hypertriglyceridemia can also result in gall stones causing cholangitis and biliary pancreatitis[25].

And when she came near she touched him with the sprig of rosemary that she carried; and his memory came back, and he knew her, and kissed her, and declared that she was his true wife, and that he loved her and no other

AML

In AML,the extra-medullary manifestations are seen in 20%-25% of children.These include chloromas(tumor nodules),skin infiltration,cerebrospinal disease,gingival infiltration,hepatosplenomegaly,or testicular involvement.In particular,AML-M4 and AML-M5 present similar to ALL with lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.Morphology and immunohistochemistry can distinguish the diagnosis[28].

Ascites is an uncommon manifestation in lymphoma.Secondary Budd-Chiari syndrome can result from compression of the hepatic veins and/or the inferior vena cava by enlarged lymph nodes.Chylous ascites(defined as ascitic fluid triglyceride more than 200 mg/dL)may rarely occur due to malignant lymph nodes obstructing the lymph flow from the gut to the cisterna chyli,resulting in leakage from the dilated subserosal lymphatics into the peritoneal cavity[57,58].The presence of chylous ascites in lymphoma portends a poor prognosis[59].Peritoneal lymphomatosis(PL)is a rare tumor originating in the peritoneum and quickly engulfs the gut,closely mimicking an acute abdomen.Most cases of primary PL have been reported in adults;however,the youngest case was seen in a 4-year-old[60,61].The differential diagnoses of peritoneal thickening include tuberculosis,pseudomyxoma peritonei,lymphomatosis,mesenteric sarcoma,and desmoid tumors.Ascites occurs in 25% of patients with Burkitt lymphoma[62].The diagnosis can often be made by paracentesis.Ascitic fluid is characteristically white(mimicking chylous ascites)with elevated lactate dehydrogenase,protein and atypical cells.Sometimes atypical cells may be missed because exfoliated mesothelial cells may predominate the cytological picture[63].Sonography in PL shows thickened lamellar omentum,hypoechoic thickened mesentery that encases vessels,and non-septate,echogenic ascites[64].CT abdomen shows omental caking,mesenteric soft-tissue nodularity along the vessels,lymphadenopathy,hepatosplenomegaly,hypoattenuating lesions in solid organs,and thickened bowel wall[60].The most common histology encountered in peritoneal involvement in adults is DLBCL and in children is Burkitt lymphoma[63].The treatment of PL is similar to Burkitt lymphoma.Although Burkitt lymphoma is chemosensitive,a large tumor burden in PL can lead to tumor lysis syndrome and rapid death[61].

Though liver involvement as hepatomegaly is lesser than ALL clinically,postmortem studies have demonstrated up to 75% involvement of the liver[29].Acute hepatitis may present as conjugated jaundice due to granulocytic sarcoma impeding bile flow or due to myeloid cell infiltration[30].Acute liver failure at presentation is rarely reported with pediatric AML posing significant challenges to chemotherapy administration and invariably had poor outcomes in the cases described in the literature[31].Coagulopathy and bleeding manifestations without other features of liver failure are the presenting features of the AML-M3 variant.This condition requires prompt institution of all-trans-retinoic acid(ATRA)along with cryoprecipitate transfusions to surpass the consumptive coagulopathy.

CML and JMML are chronic leukemias commonly described in children.Hepatomegaly is seen in 85%of pediatric CML and JMML.Liver dysfunction is uncommon.They have a more aggressive course in children than adults with higher leucocyte counts,larger spleen size,and an increased frequency of blast crisis[38].Resolution of spleen size is an important follow-up criterion in CML.JMML has a relatively younger age at onset than CML with lymphadenopathy,hepatosplenomegaly,thrombocytopenia,increased fetal hemoglobin,and a lesser overall survival than CML[28].

For some time he stumbled along, keeping to the path as well as he could in the darkness, and just as he was almost wearied out he saw before him a gleam of light

Chemotherapeutic agents used for AML include cytarabine,mitoxantrone,and daunorubicin,they can cause liver injury manifesting as hepatitis,cholestasis,and/or biliary stricture[33].Furthermore,tretinoin and arsenic trioxide used in AML-M3 can cause hepatic impairment requiring dose modifications.Pancreatitis is seen with cytarabine therapy in 5% of AML[34].

Infantile leukemias

Infantile leukemias constitute a distinct subset of hematological malignancies characterized by aggressive presentation with high leukocyte counts,infiltration of extramedullary organs,and central nervous system involvement.Contrary to the epidemiology in older children where ALL predominates AML,in infants,the incidence is equal[35].They are characterized by mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangements and frequently present with massive hepatosplenomegaly.They can present with cholestasis,elevated transaminases,or if untreated can lead to acute liver failure.Myeloid sarcoma may involve the liver particularly with chromosomal translocations involving t(1:22).Bone marrow examination may be unyielding due to marrow fibrosis,hence biopsy of the liver may clinch the diagnosis[36].Outcomes are universally poor.Transient abnormal myelopoiesis(TAM)affects 10%-15%of neonates with down syndrome(trisomy 21),with mutations in the GATA-1 gene.Immature megakaryoblasts are seen in the liver,bone marrow,and peripheral blood.The clinical presentation can be highly variable ranging from incidentally detected in an otherwise well infant to a disseminated leukemic infiltration(10%-20 % of neonates)presenting with hepatomegaly(40%),splenomegaly(30%),jaundice(70%),hepatitis(25%)and coagulation disturbances(10%-25%)[37].In TAM,liver failure can occur due to idiopathic progressive fibrosis,leukemic infiltration or iron deposition.Observation is recommended for asymptomatic cases.Chemotherapy is indicated in those with a total blast count higher than 100000/μL,organomegaly causing respiratory compromise,significant anemia resulting in cardiac failure,hydrops fetalis,life-threatening hepatic dysfunction,hyperbilirubinemia,ascites,hepatitis,and disseminated intravascular coagulation[28].The disorder usually spontaneously regresses within 3 mo.However,in 20%-30% of TAM patients,acute megakaryoblastic leukemia subsequently develops in 1-3 years[37].

Not very long after, the Princess had a baby, a little boy, but when the King her father heard of it he was very angry and afraid, for now the child was born that should be his death

Chronic leukemias

Acute abdominal pain in AML is a significant problem.Spontaneous atraumatic rupture of the spleen presents as acute abdominal pain often mimicking a surgical abdomen or gut ischemia.Kehr’s sign(acute pain in left shoulder tip)and hemoperitoneum are the hallmarks of this condition.It is more commonly associated with AML than ALL with worse outcomes.Its frequency is approximately 0.18%[32].Possible mechanisms are rapid splenic enlargement outgrowing the vascular supply,leukemic infiltration of the splenic capsule,splenic infarction,and leukemia-associated thrombocytopenia-coagulopathy.Due to improvement in imaging techniques,the frequency of detection is 9-fold higher(0.55%)presently than in the earlier era(0.06%).There is also an increased incidental detection of “preclinical” splenic rupture.In this subset,30% do not have palpable spleens[32].Adolescent age group,acute promyelocytic leukemia variant,high leukocyte count at presentation,fungal infection,thrombocytopenia,and coagulopathy may predispose to pathologic splenic rupture[32].The overall incidence of typhlitis in acute leukemias in children is 4%-5% with a higher cumulative risk in AML than ALL[12].

This next morning also he peeped in at the door, but what he saw there surprised him so much that he shut the door in a hurry, and hastened to the king and queen, who were waiting for his report

His behavior often left us without funds for other more important things. After the dress incident, there was no money for the winter coat I really needed--or the new ice skates I wanted.

Clinical impact of leukemias for the gastroenterologist

Acute leukemias that present with febrile hepatitis are often initially mistaken for infectious and immunological causes.Most patients have elaborate workup and multiple failed antimicrobial therapy before the diagnosis is ascertained.The diagnosis is often made on peripheral smear by a seasoned hematopathologist when atypical cells are identified.Drug-induced hepatotoxicity is a serious concern as many drugs are precluded and the outcome of the disease is modified.GI symptoms require prolonged proton pump inhibitor therapy till the end of the induction phase.An acute abdomen may need to be evaluated for typhlitis,pancreatitis,or spontaneous splenic rupture.Typhlitis in leukemias often leads to a complicated course requiring gut rest,prolonged antibiotic therapy.Since appendicitis is a close differential diagnosis,there is a considerable dilemma for the surgeon whether to perform a laparotomy in a state of neutropenia[39].Pancreatitis during chemotherapy may have an underlying genetic predisposition and may need exploration before induction.Bloody diarrhea is ominous for a colonic involvement such as a superinfection with

in a neutropenia state.These complications need to be timely managed to avoid prolonged chemotherapy interruptions which may otherwise impact relapse rates.CML presenting with massive splenomegaly is often worked up for other differential diagnoses such as tropical splenomegaly syndrome,kala-azar,and extrahepatic portal hypertension in developing countries.

Looking at this, the lawyer thought maybe there s still a chance, but the wife was frowning7 when she answer. This is always the problem, you always think so highly8 of yourself, never thought about how I feel, don t you know that I hate drumsticks?”

LYMPHOMAS lN CHlLDREN

Combined,Hodgkin’s disease(HD)and non-Hodgkin lymphomas(NHL)are the third most common malignancies in children and adolescents,with HD being the most common cancer in children between the ages of 15-18 years[40].It is important to determine whether extranodal involvement represents a primary manifestation or is a part of a disseminated disease,which may have a poorer prognosis[41].Extranodal disease is present in 12% of HD.Extranodal involvement is more common in older(10-17 years:14%)than younger children(0-9 year:4%)[42].

I suspect my colleague Matt Pritchett might be with me on this. One of his cartoons this past week showed a father next to a television tuned13 to the World Cup, explaining to his children that at some point in the next few weeks, you are going to see me cry . And the day after the last survivor14 of the Great Escape died, he did a cartoon showing a gravestone with a mound15 of tunnelled earth trailing away from it. I seemed to have something in my eye when I saw that, and I expect he had the same something in his eye when he drew it.

Hepatobiliary involvement

Liver involvement is less frequent in HD than in NHL.Five percent of patients with HD have liver involvement at the time of diagnosis[43].Usually,hepatomegaly is present when the liver is involved.However,liver size can rarely be normal despite infiltration.Smaller lesions are more common than large masses[41].HD of the liver is almost invariably associated with disease of the spleen.The more extensive the splenic disease,the greater the likelihood of hepatic involvement[43].In HD,lymphomatous cells may infiltrate the liver in up to 15% of patients with hepatomegaly and 45% in the later stages of the disease.Jaundice as a presenting symptom in HD is seen in 3%-13% of patients[44].On many occasions,the diagnosis of HD can be misled by the presence of granulomas in liver biopsy specimens.A false impression of tuberculosis and unwarranted empirical antitubercular therapy is commonly encountered where there is a high community prevalence.Excision biopsy of palpable lymph nodes and imaging-guided biopsy of representative areas distinguishes the condition[45].Acute liver failure can rarely occur in the setting of hepatic infiltration.One of the mechanisms by which malignant infiltration may cause liver failure is ischemia secondary to the compression of the hepatic sinusoids by the infiltrating cells[46].Cholestasis can occur as a result of direct infiltration,extrahepatic biliary obstruction,hemolysis,viral hepatitis,or drug hepatotoxicity[44,47].In HD,cholestasis in zone 3 has also been described due to vanishing bile duct syndrome where there is an irreversible destruction of the small intrahepatic bile ducts and significant liver damage[47].The mechanism by which this syndrome occurs is poorly understood but may be a paraneoplastic effect,a defect in liver microsomal function,or a toxic effect of cytokines released from lymphoma cells[48].Other causes of this vanishing bile duct syndrome should be considered in the differential diagnosis before attributing it to HD[44].Even with adequate treatment of lymphoma,most of these patients die of progressive liver dysfunction and failure.Their course becomes further tenacious due to the preclusion of potentially hepatotoxic agents[48].

The four common childhood NHL include Burkitt lymphoma,lymphoblastic lymphoma,diffuse large B-cell lymphoma(DLBCL),and anaplastic large cell lymphoma.Lymphomatous infiltration and extrahepatic obstruction occur more commonly in NHL than in HD;16% to 43% of patients with NHL have liver involvement.Mild to moderate increases in alkaline phosphatase level and hepatomegaly commonly occur in NHL even without lymphomatous hepatic involvement[47].As described earlier with HD,acute liver failure can also occur in NHL.The mechanism by which this occurs is likely similar to that in HD,with sudden ischemia related to massive infiltration of the sinusoids or replacement of liver parenchyma by malignant cells[46].This condition should be suspected when a patient presents with new-onset hepatomegaly and lactic acidosis.Prompt evaluation including liver biopsy should ensue[47].Although the prognosis is poor,there have been reports of successful treatment with immediate initiation of chemotherapy in this subset of patients.Cholestasis may be additionally be caused by compression of enlarged periportal and peribiliary lymph nodes.Ghosh

[49]described a cohort of nine children with NHL who presented with jaundice as the primary presentation which constituted 11.2% of all NHL.Total bilirubin and liver enzymes ranged from 2.9-19.6 mg/dL and 55-654 U/L respectively.All had raised alkaline phosphatase ranging from 957-3786 U/L.Seven patients had biliary obstruction with periampullary,periportal,gastroduodenal,or subhepatic masses on imaging.Two patients had liver parenchymal infiltration without biliary obstruction.Histology of these patients with biliary obstruction was anaplastic large cell,high-grade Bcell,and Burkitt lymphoma.Biliary drainage was performed in one patient.Seven patients had amelioration of jaundice with chemotherapy alone in 10-46 d[49].Published case reports and small series have used surgery,biliary drainage,steroids,and cytotoxic agents in various combinations and sequences.Waiting for serum bilirubin to normalize after biliary drainage or treating only with steroids may compromise the outcome of patients.Also,chemotherapy after biliary drainage has been associated with complications such as biliary leak and peritonitis[50].

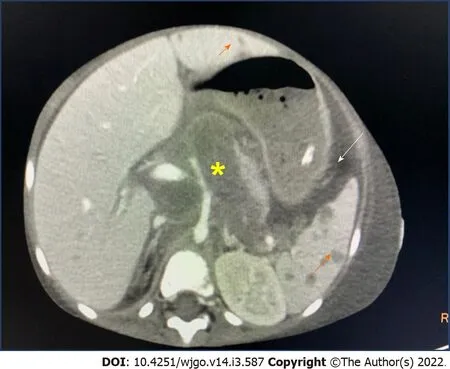

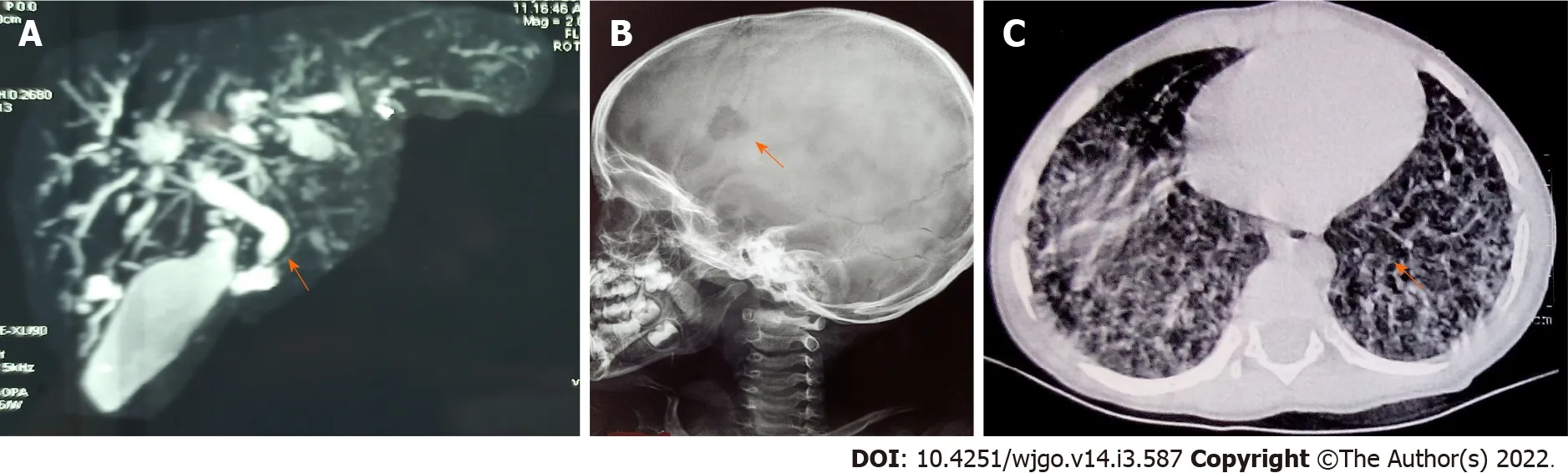

In NHL,discrete lesions can be noted on CT scans.Liver biopsy is the most accurate method for confirmation of liver involvement[51].Diffusely increased or focal uptake,with or without focal or disseminated nodules supports liver involvement(Figure 1).Discrete nodular lesions are seen in only 10% of cases.HD manifests more often as miliary lesions(< 1 cm in diameter)than as masses.The diffuse or infiltrative form of the disease results in patchy,irregular infiltrates originating primarily in the portal areas[41].In current practice,fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computerized tomography(FDG-PET-CT)is the reference standard for both staging and follow-up of HD and NHL.If an FDG-PET-CT is performed,a bone marrow examination can be avoided for HL.Bone marrow examination may be only needed for suspected DLBCL where there is a discordance between suggestive histology but negative PET[52].

Then she cracked her second nut, and all the forest behind her seemed to be in fire and flames, and the evil spirits howled even worse than on the previous day; but the contract they would not give up

Empiric dose reductions in chemotherapy are usually recommended in jaundiced patients.Guidelines recommend a 50% dose reduction of etoposide in the presence of serum bilirubin 1.5-3 mg/dL and omitting the drug if serum bilirubin is greater than 3 mg/dL.For etoposide,pharmacokinetics in the presence of hepatic dysfunction has been determined in very few studies.In the presence of elevated serum bilirubin,there is no robust data to guide the dose modification of ifosfamide and cytarabine[53].Neurotoxicity of high-dose cytarabine may worsen with elevated serum bilirubin but there are no guidelines to suggest a modification.Methotrexate is metabolized by the liver and excreted through the kidney.In those with preexisting hepatic dysfunction,methotrexate has the potential to cause further hepatic insult and hence is mostly withheld or administered in reduced doses[53].However,in the pediatric NHL series,some authors have used doses higher than that recommended without reporting any organ dysfunction or mortality due to drug toxicity[49].Ballonoff

[54]reviewed 37 adults with NHL and found an association between an improvement in cholestasis and complete response to chemotherapy or radiation therapy(or both).

GI and pancreatic involvement

Pancreatic HD is extremely rare and,in almost all cases,secondary to contiguous lymph node disease.Since the pancreas has no definable capsule,it may be difficult to distinguish an adjacent lymph node disease from intrinsic pancreatic infiltration[41].The prevalence of pancreatic involvement in pediatric Burkitt lymphoma is between 4% to 10%[55].CT shows focal pancreatic enlargement with patchy areas of non-enhancement.Marked dilatation of the biliary system can occur when a mass infiltrates the pancreatic head[56].HD involving the GI tract is rare as compared to NHL.Extra-nodal involvement(except in the spleen,Waldeyer’s ring,and thymus)indicates stage IV HD[41].

Ascites in abdominal lymphoma

She had hardly smelt74 it for an instant when she declared herself to be perfectly restored; but whether that was due to the scent75 of the wood or to the fact that as soon as she touched it out fell a perfect shower of magnificent jewels, I leave you to decide

Clinical impact of lymphomas for the gastroenterologist

Lymphomas presenting as cholestasis need a liver biopsy for diagnosis.In a setting of thrombocytopenia,a plugged percutaneous transhepatic or transjugular liver biopsy may be required.The presence of a granuloma is misleading for other differential diagnoses.In developing countries,many months of exposure to antitubercular therapy(for assumed disseminated tuberculosis)is common before a diagnosis of abdominal lymphoma is made.Vanishing bile duct syndrome has a poor prognosis.Often major lymph nodes are found around the periportal or peripancreatic areas in cholestasis.CT-guided biopsies risk chances of gut perforation of the overlapping small bowel.In such situations,tissue sampling can be challenging.Peribiliary and upper abdominal retroperitoneal lymph nodes are best accessed by pediatric endosonography in a specialized center.Linear endosonography is difficult to perform in a very young child as appropriately sized scopes are unavailable.Hence laparoscopy or laparotomy-based sampling is the final choice especially if the above techniques fail or lymph nodes are deep mesenteric or perivascular.Therapeutic endoscopic cholangiopancreatography and stent placement for biliary drainage are challenging in children.Ascites in lymphoma requires careful evaluation for an underlying source.PL has a universally poor prognosis.

PRlMARY LYMPHOMAS lN CHlLDREN

Primary lymphomas in children can involve the GI tract[primary GI lymphoma(PGIL)],spleen(primary splenic lymphoma),liver[primary hepatic lymphoma(PHL)],and combination of spleen and liver[hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma(HSTCL)].The diagnosis of primary lymphomas is considered if the bulk of the tumor is restricted to the organ of its origin after thorough staging and in the absence of distant lymphadenopathy or blood involvement(peripheral blood smear or bone marrow).

PHL

Criteria for diagnosis of PHL include symptoms caused mainly by liver involvement(palpable clinically at presentation or detected during staging radiologic studies)at presentation,absence of distant lymphadenopathy,and absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear.PHL usually occurs in the 5

-6

decade and has been reported rarely in children[65,66].The most common presentation is abdominal pain due to hepatomegaly.B symptoms of fever and weight loss occur in onethird of patients.Citak

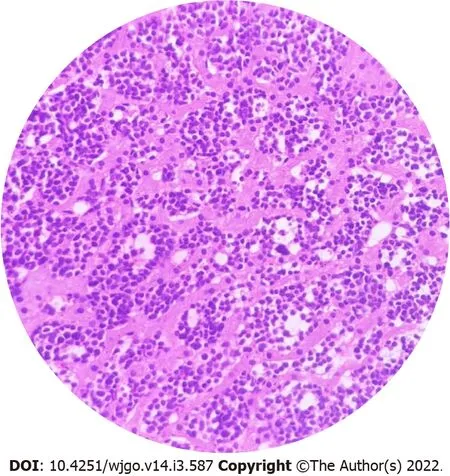

[67]in a review of literature of 10 children with PHL reported male preponderance.The presenting features were enlarging hepatomegaly,nonspecific symptoms of anorexia,fatigue and abdominal pain.Serum alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels are increased in 70% of cases.The most common type of primary hepatic NHL is DLBCL,comprising 80%-90% of the cases(Figure 2).This disease may present with nodules in the liver or diffuse portal infiltration and sinusoidal spread[68].

When she got home she ran to seek out her godmother, and, after having thanked her,52 she said she could not but heartily37 wish she might go next day to the ball, because the King s son had desired her.

Most cases of PHL present with solitary or multiple mass lesions in the liver on imaging,diffuse involvement can also occur but is less common[65].A solitary lesion is the most frequent finding which is encountered in 50% to 60% of cases.Estimating the prognosis of PHL is difficult because the condition is rare.Nodular,as opposed to diffusely infiltrative disease,may have a more favorable outcome with chemotherapy,with 3-year survival rates of 57% and 18%,respectively.PHL has also been described more often in those with immunodeficiency states,systemic lupus erythematosus,chronic hepatitis B,and chronic hepatitis C in adults[66].Differential diagnoses of nodular PHL would be hepatocellular carcinoma,hepatoblastoma,liver embryonal sarcoma,metastatic neuroblastoma,liver rhabdomyosarcoma and hepatic Ewing's sarcoma[67].There is a shift in paradigm from primary surgery to primary chemotherapy avoiding extensive hepatic lobectomy[65].Early and aggressive anthracyclinebased combination chemotherapy may result in prolonged remissions in PHL patients[69].In situations where lymphoma presents as acute liver failure,it is often difficult to distinguish from PHL.Liver transplantation and subsequent chemotherapy are viable options in such scenarios[70].

HSTCL

HSTCL is a rare,aggressive lymphoma that infiltrates the hepatic sinusoids.In HSTCL,there is a diffuse hepatic sinusoidal and splenic sinus infiltration with clonal populations of gamma-delta T cell receptor expressing cells.Cytogenetic analysis commonly reveals an isochromosome 7q and trisomy 8[71].Male patients younger than 35 years with inflammatory bowel disease and at least a 2-year history of exposure to combined thiopurine and biologic therapy may be at increased risk for developing HSTCL.Diak

[72]reported 9 cases of HSTCL in the age group of 12-22 years receiving biological therapy and concomitant immunosuppression with thiopurines with or without steroids.During immunosuppression,thiopurines induce apoptosis,and this feature allows escape from tumor surveillance possibly leading to the development of malignancy.This situation,together with the effect of biological therapy on T cells(complement-mediated lysis and apoptosis),may partially explain as to why patients treated with these agents are at risk of HSTCL.Patients typically have hepatosplenomegaly,abnormal liver function tests,fever,weight loss,night sweats,pancytopenia,and peripheral lymphocytosis[72].Bone marrow is involved in virtually all patients at the time of diagnosis.If HSTCL is suspected,a bone marrow biopsy(including immunophenotyping)should be performed to confirm the diagnosis[71].Lymphadenopathy is usually absent.Histology can mimic autoimmune hepatitis and may often lead to misdiagnosis.With the increasing number of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease cases and the poor outcome of HSTCL,practice guidelines suggest thiopurines should be withdrawn from combination therapy after 6 mo in ulcerative colitis and 6-12 mo in Crohn’s disease.This is preferably performed after checking adequate trough levels of anti-tumor necrosis factor agent and treatment target has been achieved[73,74].

PGIL

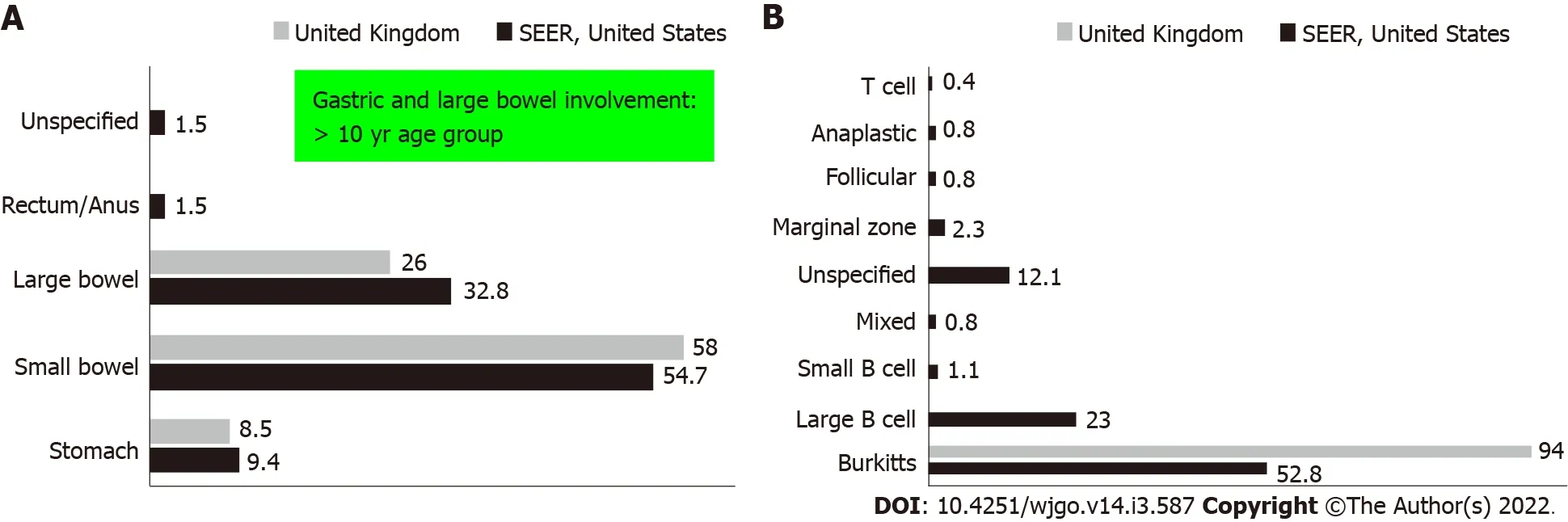

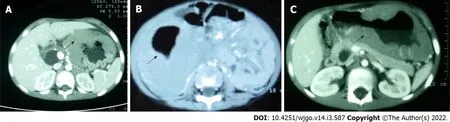

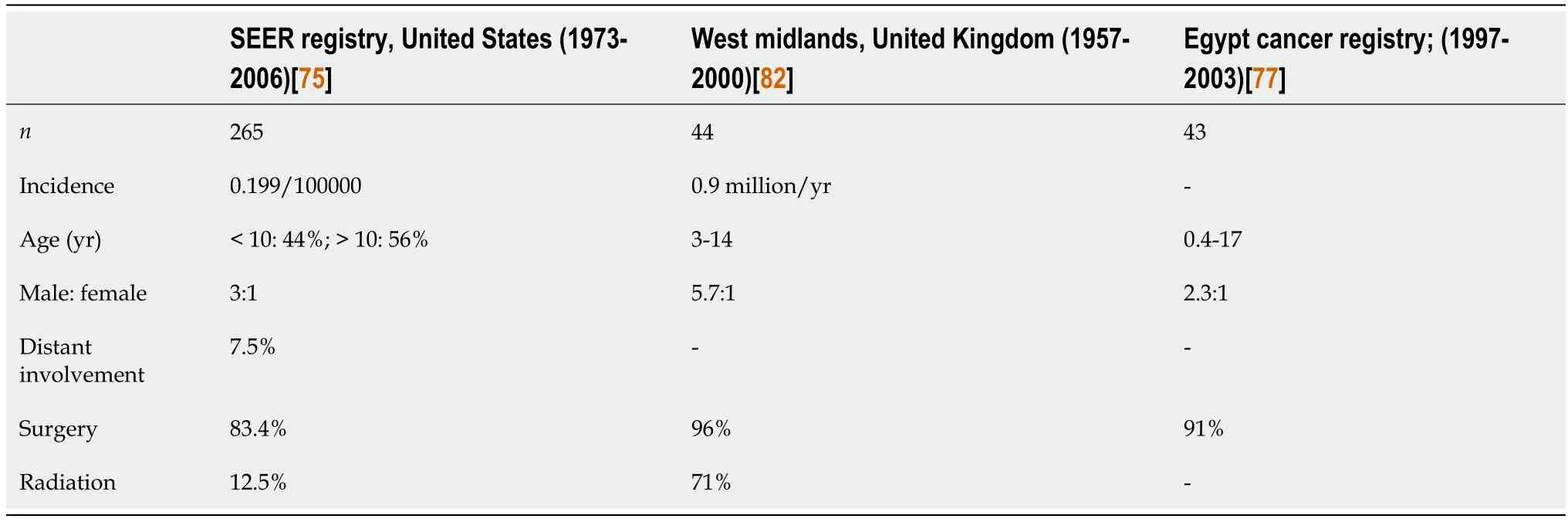

PGIL represents less than 5% of all pediatric neoplasms and is the most common bowel malignancy in childhood[75](Table 2).Among its types,NHL is the most common malignancy of the GI tract in children.PGIL is less frequent than secondary GI involvement of nodal lymphoma.They are important since their evaluation,diagnosis,management,and prognosis are distinct from that of lymphoma at other sites and other cancers of the GI tract[75].Criteria for PGIL suggested by Dawson is the presence of tumor bulk in the GI tract with minimal locoregional abdominal lymphadenopathy and characteristic absence of peripheral,mediastinal lymphadenopathy,hepatosplenomegaly,and normal blood cell counts[76].The peak age for NHL of GI tract in children is 5-15 years.Surveillance,Epidemiology and End Results(SEER)registry from United States(1973-2006)showed the frequency of PGIL < 10 years and > 10 years as 44% and 56% respectively with higher male predilection(3:1)[75].Small followed by large bowel are the most common sites in children,unlike adult patients where the stomach(50%-60%)is the most common site[75](Figure 3A).The terminal ileum is the most commonly reported location in children,due to the high concentration of lymph tissue in that region of the bowel[76].The mostcommon presenting features are abdominal pain(81.4%)and abdominal lump(76.7%).Intestinal obstruction at presentation is seen in 11.6%[77].Due to the absence of a desmoplastic response,the tumor grows along with walls.Bowel obstruction is initially uncommon until intussusceptions occur or tumor bulk becomes proliferative towards the lumen in the later part of the disease[78].Of the PGIL,Burkitt lymphoma is the most frequent histological subtype in children[75](Figure 3B).A typical morphological feature in Burkitt lymphoma is lymphoblastic cells having round nuclei with clumped chromatin and multiple,centrally located nucleoli giving the characteristic starry sky- appearance[79].Sometimes it may not be possible to distinguish PGIL from secondary involvement in advanced cases when tumor bulk is high.Nearly half of children with GI NHL have tumor infiltrate confined to the GI tract with possible regional lymph node involvement.Imaging findings on CT include a diffuse or focal thickening of the stomach and/or bowel wall(Figures 4A,4B and 4C).Aneurysmal dilatation of the bowel can be seen in nearly one-third of patients due to irregular growth in the muscularis propria and/or destruction of the autonomic nerve plexus[76].Almost all the reported cases of appendicular lymphoma are due to NHL,seen as young as 3 years of age[80].Pediatric NHL staging systems are St.Jude’s and Revised International Pediatric NHL staging system[81].The treatment approach in PGIL is debatable.

Proponents of surgery in the past argued that the disease is better debulked before chemotherapy to decrease tumor lysis syndrome,lessen the spread,and lessen the cumulative chemotherapy.Opponents who favored chemotherapy felt that upfront surgery had higher post-operative complications,effectively delayed starting of chemotherapy,and lead to poor long-term outcomes.Systematic review and meta-analysis compared surgery

chemotherapy.It was seen that upfront surgery and chemotherapy in < 10 years of age showed near similar 5 and 10-year survival(83%-85%)in both groups.In those > 10 years of age,there was a significant statistical difference in the 5 and 10-year survival rates in the upfront surgery(79%)

upfront chemotherapy(100%)groups[75].Systematic reviews showed better 10-year disease-free survival and lesser recurrence in the medical group but higher mortality in the surgical group[75,77,82].Chemotherapy alone seems to be the most effective treatment option in all stages of PGIL.Presently surgery is not indicated unless there are complications like perforation,hemorrhage,or obstruction which cannot be managed conservatively[83].Further studies are needed to evaluate outcomes for patients with localized or distant disease,partial or complete resection,and the effect of adjuvant radiotherapy[75].In terms of location,tumors located in the stomach,small bowel,colon,and rectum have 10-year survival as 64%,86%,83%,and 100%,respectively[75].

Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease

Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease(IPSID)is a unique lymphoproliferative disease that presents as malabsorption,anemia,pain abdomen,and protein-losing enteropathy.It is predominantly seen in adults but rarely also in adolescents.Blunting of villi and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with atypical lymphoid cells is the characteristic of small bowel histology.Diagnostic laparotomy for fullthickness small bowel biopsy and adjacent lymph nodes sampling is required with various systems of grading.Serum alpha heavy chain abnormal immunoglobulin A is pathognomonic by immunoelectrophoresis.Advanced IPSID presenting as abdominal mass is indistinguishable from lymph nodal lymphomas with secondary bowel involvement.Early disease is treated with antibiotics with a 33%-71%response[84].Advanced IPSID needs chemotherapy and is associated with a poor prognosis[85].IPSID is a close differential diagnosis for enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma which is seen in adults with underlying celiac disease.

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder

Lymphomas originating from the GI or HB tract have a unique presentation.Due to their rapid infiltrative capacity,the disease is usually contained within their sites of origin before spillover into the blood or distant sites.Hence organomegaly and abdominal lump are the main presentations.PHL mimics storage disorders and congestive livers.PGIL mimics abdominal tuberculosis,intra-abdominal tumors,and large fungal masses such as basidiobolomycosis[89].PGIL located in the upper GI tract or colon is amenable to endoscopic mucosal biopsies though often unyielding.Hence radiological guided needle biopsies are necessary to sample from deeper layers.A similar problem is encountered in IPSID.Diagnostic laparotomy is often required.

There was a moment of silence, then everyone but the Princess began to laugh. In fact, they laughed and they laughed, which made the little blacksmith s ears turn red. The King said, You are no match for this dragon. It takes might to fight. You are simply too small.

Clinical impact of primary lymphomas for the gastroenterologist

Lymphoma in post-transplant recipients has been reported with the possible mechanism of continuous B-cell proliferation,which is normally inhibited by T-lymphocytes.Both solid organ and hematopoietic stem-cell transplant recipients are at risk for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder(PTLD),a type of NHL driven mostly by Epstein-Barr virus infection.PTLD is associated highest with heart-lung,small bowel,and liver transplantations[86-88].Liver and spleen involvement in PTLD is not unusual,occurring in 16% of patients over 20-years[85].If present in the liver,PTLD can cause intrahepatic cholestasis or extrahepatic cholestasis from bulky lymphadenopathy around the porta hepatis.

LCH

The hallmark of LCH is the accumulation of LC-like dendritic cells in one or more tissues or organs.The clinical manifestations of LCH are highly diverse and result both from direct(local effects of the growth and accumulation of pathologic LCs)and indirect effects(secondary changes on normal tissues,particularly cells of the immune system).The reported incidence of LCH ranges from 2.6 to 8.9 cases per million children younger than 15 years per year,with a median age at diagnosis of 3 years[90].Pathologic LCs are clonal and nearly 60% of LCH samples carry the oncogenic BRAF V600E variant[90].The characteristic histopathology required for a “presumptive diagnosis” usually shows a granulomatous-like lesion with immature dendritic-appearing cells that have characteristic bean-shaped,folded nuclei and pale cytoplasm.Often,multinucleated giant cells are present.A “definitive diagnosis” of LCH requires the immunohistochemical identification of the presence of Langerhans cell antigen expression of cell surface CD1a,CD207(langerin),or by the presence of cells with Birbeck granules by electron microscopy.Early in the course of the disease,the lesions are usually proliferative and locally destructive.In later or healing stages,they can become more fibrotic[91].The skeleton is the most commonly affected system,as bone lesions are present in approximately 80% of patients with LCH,and in half of them,lesions are single[90,92].In infants with initially localized disease,progression to a multisystemic involvement(Figures 5A,5B and 5C)has been observed in up to 40% of cases[90].LCH can involve almost all organ systems and clinically risk organ involvement is defined as infiltration of the liver,spleen,bone marrow,and lung with the former three constituting high risk organs[93].

Hepatobiliary involvement

Liver is considered as a risk organ in staging of LCH with reported involvement ranging from 15%-60%and portends poor prognosis[94].Liver involvement in LCH needs fulfillment of one or more of the following:Liver enlargement > 3 cm below the costal margin in the midclavicular line,liver dysfunction(

:Hypoproteinemia < 55 g/L,hypoalbuminemia < 25 g/L,hyperbilirubinemia > 1.5 mg/dL,edema or ascites,not as a result of other causes)or histopathological findings of active disease[90].Yi

[95]in a study of 31 children with LCH described hepatomegaly in 42%,jaundice in 16%,and splenomegaly in 19%.Hepatic involvement in LCH typically presents with hepatomegaly due to the direct infiltration by Langerhans cells.Hepatomegaly may also be due to Kupffer cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia secondary to a generalized immune reaction or by enlarged portal lymph nodes causing an obstruction.Presentation is typical with cholestasis and recurrent cholangitis.Biochemically there is a significantly elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transferase.Liver biopsy shows features of sclerosing cholangitis,periductal fibrosis,and bile duct proliferation.Liver biopsy is only recommended if there is clinically significant liver involvement and if the results of the same are likely to alter treatment in an otherwise diagnosed case of LCH(

to differentiate between active LCH and other causes of sclerosing cholangitis)[91].The absence of Langerhans cells or CD1a positivity usually represents a burnt-out liver and has a poor response to chemotherapy.Since the disease process is usually found around the major bile ducts,a blind liver biopsy may miss the LCH infiltration[94].Diagnostic imaging can visualize areas of LCH infiltration that may be missed on biopsy.Findings on liver imaging correspond to four progressive histological phases:Proliferative,granulomatous,xanthomatous,and the final fibrous phase.The proliferative and granulomatous phases show periportal histiocyte infiltration,inflammation,and edema which appear as periportal hypoechoic and relatively well-demarcated lesions on sonography.On CT,these lesions appear hypodense,and post-contrast enhancement is thought to reflect portal triaditis.Magnetic resonance imaging(MRI)shows hypointensities on T1-W images and hyperintensities on T2-W images.In the xanthomatous stage,periportal fatty lesions appear hyperechoic on sonography.They remain hypodense on CT images.On MRI,these lesions are hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2[96].The fibrous stage is characterized by progression to periductal fibrosis and micronodular biliary cirrhosis which results from sclerosing cholangitis.In thisstage,sonography demonstrates well-demarcated periportal hypoechoic lesions with spotty calcification.Dilatation and beading of the biliary ducts,consistent with sclerosing cholangitis,can be seen with conventional cholangiography and MR cholangiopancreatography[96].The hallmark of biliary involvement is an extrahepatic or intrahepatic sclerosing cholangitis that may occur in 10%-18%of patients with the multisystem form of LCH[97].Sclerosing cholangitis may lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis,portal hypertension,and liver failure.Variceal bleeding is a frequent issue in portal hypertension requiring variceal banding or sclerotherapy.Braier

[97]showed a 25% response to chemotherapy in LCH-sclerosing cholangitis.The rest either underwent liver transplantation or died.Sclerosing cholangitis is usually progressive and in these children,often the only successful treatment is liver transplantation[91,97].Several poor prognostic factors are associated with survival like hepatic involvement,age < 1 year,and incomplete response to treatment.Three-year survival rates with and without liver involvement are 51.8% and 96.7% respectively[95].The dominant extrahepatic biliary strictures persist despite chemotherapy and may need repeated endoscopic biliary dilatation.Therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and biliary stent placement may be daunting in younger children where appropriate-sized endoscopes and accessories are not available.Repeated procedures in children expose them to greater radiation from fluoroscopy and adversely affect their long-term outcomes.

GI involvement

GI involvement is seen in less than 5% of cases commonly presenting as diarrhea,malabsorption,hematochezia,anemia and hypoproteinemia[98].In a review of literature by Hait

[99],of 22 children with LCH having GI involvement,86% of patients presented before 1 year and 95% before 18 mo of age with 91% showing biopsy suggestive of LCH.Those with multiorgan involvement had higher mortality.Diarrhea,malabsorption,protein-losing enteropathy,and hematochezia are common manifestations ofLCH involving the GI tract[91].

I realized I needed a better explanation; how could a three-year-old know what June meant? Just then, as Justin climbed into the low branches of the plum tree, he gave me the answer I was looking for... his special tree.

Clinical impact of LCH for the gastroenterologist

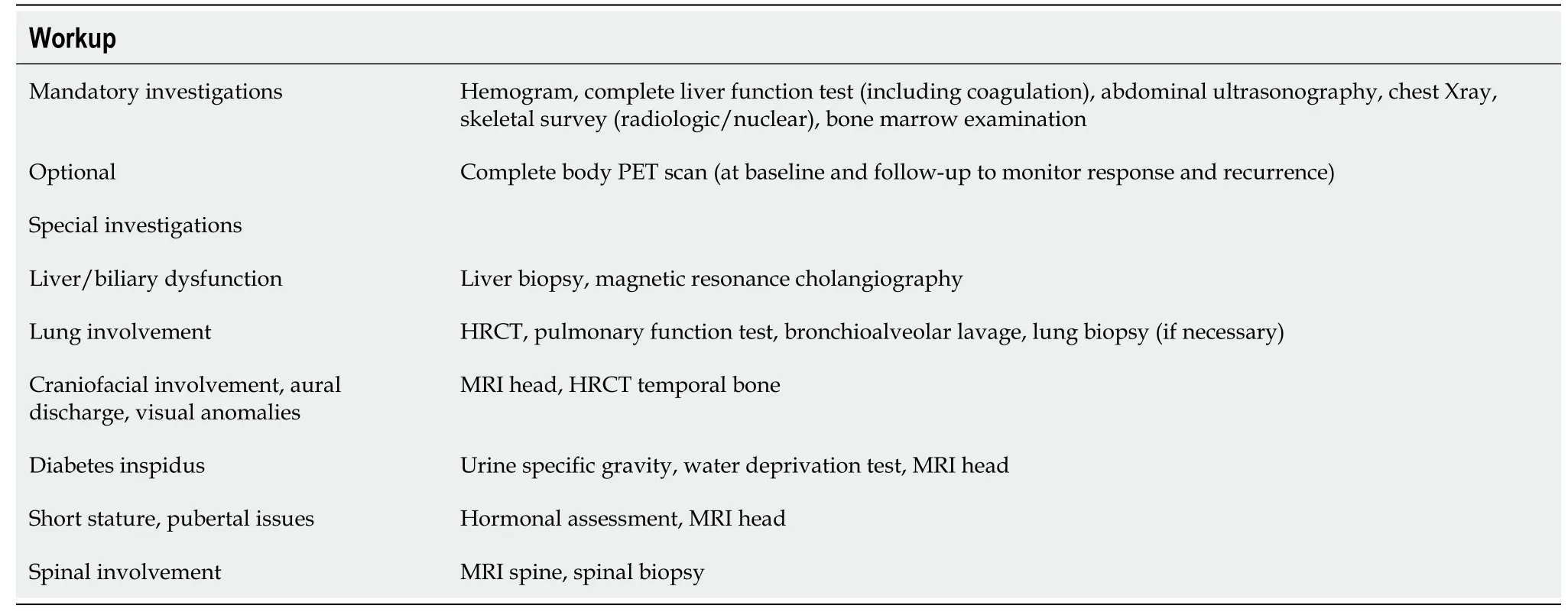

LCH is a complex disorder that is easier to diagnose clinically if there is a multisystemic presentation than isolated GI or HB involvement.Tissue diagnosis is definitive and a detailed workup for multisystemic involvement is important for management and prognosis(Table 3).The current standard of care for front-line therapy of patients with multifocal LCH or unifocal disease in CNS-risk sites is vinblastine/prednisone for 1 year,with the potential addition of 6-MP for high-risk LCH.Newer drugs such as vemurafenib are used to treat BRAF V600E mutation-positive,refractory,childhood LCH[100].For those developing life-threatening diseases during treatment,alternative aggressive treatment should be considered,including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.In the natural history,isolated HB disease is often treated as primary sclerosing cholangitis for many years till the disease evolves into a full-blown systemic problem or involves another site(bones,lungs,

).Hence guidelines for sclerosing cholangitis in children require ruling out LCH effectively[101].Recurrence rates in multisystem low-risk disease are lower in 12 mo than 6 mo of therapy.It is unclear whether further prolongation of therapy will ameliorate sclerosing cholangitis[91].Since the majority of HB involvement is a reflection of a burnt-out disease,children on chemotherapy must be preemptively waitlisted for tentative liver transplantation.Dominant extrahepatic biliary strictures require biliary drainage for control of cholangitis and intractable pruritus that affect the quality of life.

The robber-girl looked earnestly at her, nodded her head slightly, and said, “They sha’nt kill you, even if I do get angry with you; for I will do it myself.” And then she wiped Gerda’s eyes, and stuck her own hands in the beautiful muff which was so soft and warm.

NON-PHARMACOLOGlCAL lNTERVENTlONS lN PEDlATRlC HEMATOLYMPHOlD MALlGNANClES

The advances in supportive care have uplifted the survival curves dramatically in childhood hematolymphoid malignancies.Non-pharmacological management includes the appropriate use of interventional and non-interventional approaches tailored to the clinical scenario.The decision of proceeding with endoscopic or surgical intervention for an acutely ill child with cancer requires improved interdisciplinary communication and logistics in place.The various endoscopic interventions include biliary stenting by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP)for cholangitis due to lymph nodal biliary obstruction and endoscopic balloon dilatation for dominant biliary strictures in sclerosing cholangitis[50].Endoscopic percutaneous gastrostomy can be considered for optimizing nutrition in children with severe malnutrition,severe oral mucositis or anorexia.Similarly,antral stents can be deployed endoscopically for improving nutrition and palliation in malignant gastric outlet obstruction by lymphoma.Endoscopic closure with hemoclips(through the scope or over the scope)has been attempted in luminal perforations in GI lymphoma but this may be technically difficult and unrewarding.In ductal disruption/disconnected duct syndrome due to pancreatitis,pancreatic duct stenting can be attempted.Endoscopic or endoscopic ultrasound guided drainage for symptomatic pancreatic collections is performed in drug-induced severe pancreatitis.Radiological interventions include percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage(for strictures proximal to liver hilum or after failed ERCP)and drainage of abdominal collections(after a sealed perforation or if the child is not a candidate for surgery).Pediatric hematolymphoid malignancies are both chemo and radiosensitive,hence the role of debulking surgery is limited to high-grade GI lymphomas presenting with emergencies such as bowel obstruction due to intussusception and extrinsic nodal compression[102].Gut perforation,typhlitis and uncontrolled GI bleed may necessitate emergency laparotomy.In children with LCH,sclerosing cholangitis can progress to biliary cirrhosis necessitating salvage by a liver transplant.In liver failure,the use of liver assist devices like Prometheus,molecular adsorbent recirculation system can act as a bridge for liver transplantation.

Non-interventional approaches aim at optimizing nutrition,psychosocial support and judicious use of blood products.Nutritional compromise is multi-factorial and occurs mostly due to cancer-induced anorexia and emetogenic chemotherapeutic drugs.Hence ensuring nutritional rehabilitation through an energy-rich high protein diet and promoting a good psychosocial environment can lead to early recovery of these children[103].In special circumstances like chylous ascites due to lymphatic infiltration by neoplastic cells,transient dietary modifications include the use of medium-chain triglycerides and restricting intake of long-chain triglycerides.

APPROACH TO COMMON GUT AND LlVER MANlFESTATlONS OF HEMATOLYMPHOlD MALlGNANClES lN CHlLDREN

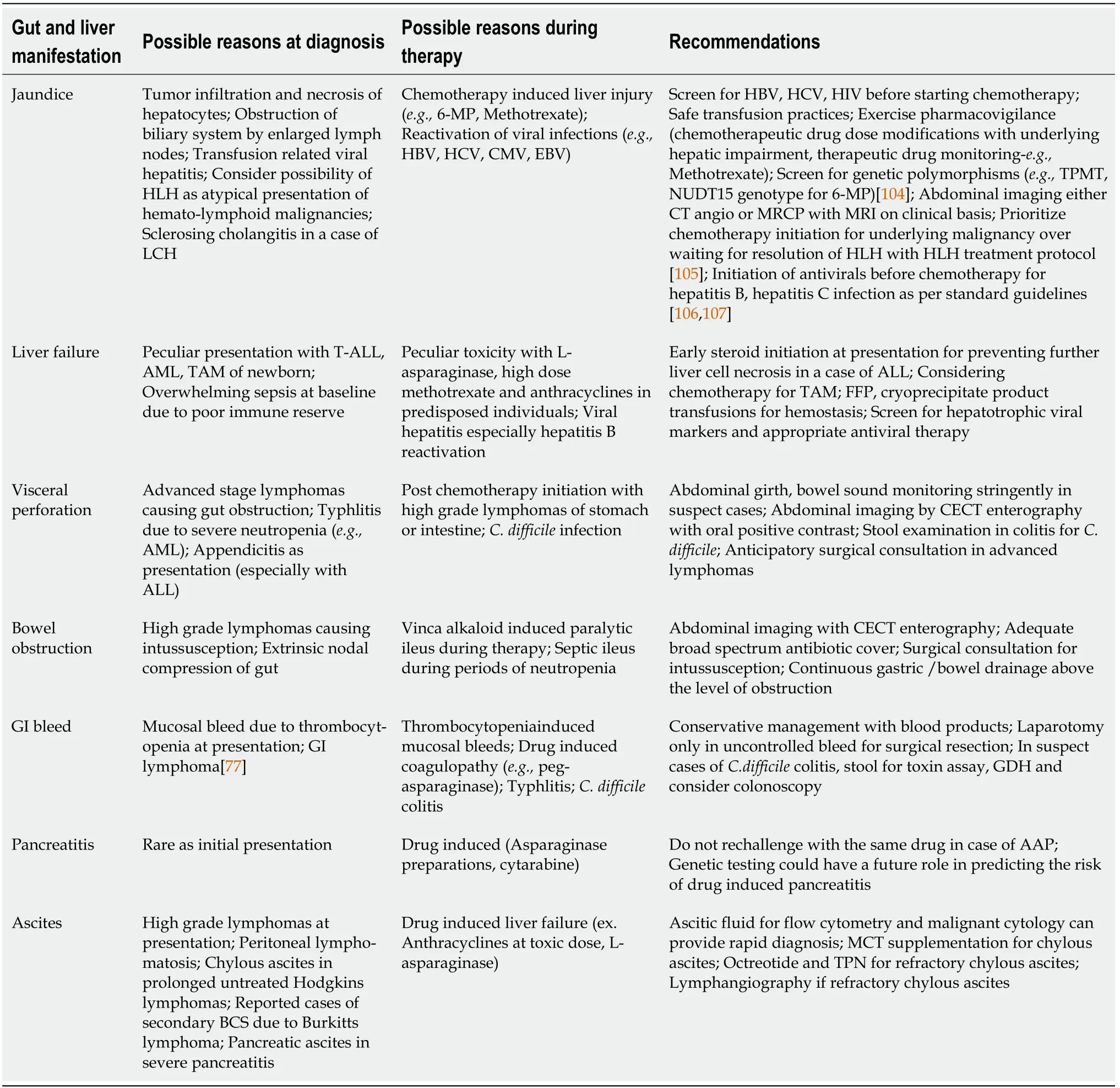

A summary of the clinical features and the recommendations are listed below(Table 4).

CONCLUSlON

GI and hepatobiliary manifestations of hematolymphoid malignancies in children present with a multitude of symptoms ranging from subtle manifestations like asymptomatic organomegaly to moribund presentations like acute liver failure.The crux lies in establishing a diagnosis of malignancy while differentiating it from chronic infectious and inflammatory conditions.Use of invasive procedures such as guided biopsies and endoscopic interventions should be urged at the earliest window to avoid delay in therapy initiation in hematolymphoid malignancies with such atypical presentations.Pharmacovigilance should be practiced while using chemotherapeutic drugs to avoid hepatic and GI impairment.A prior thorough overview of specific manifestations and distinct drug toxicities by the physician would aid in optimal clinical management.

FOOTNOTES

Devarapalli UV,Sarma MS and Mathiyazhagan G contributed to the literature review;Devarapalli UV and Mathiyazhagan G contributed to the primary drafting;Sarma MS reviewed concept and design,intellectual inputs,and final drafting.

Authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial(CC BYNC 4.0)license,which permits others to distribute,remix,adapt,build upon this work non-commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms,provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial.See:https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

India

Umeshreddy V Devarapalli 0000-0003-0224-4474;Moinak S Sarma 0000-0003-2015-4069;Gopinathan Mathiyazhagan 0000-0002-1643-2129.

Wang JJ

A

Wang JJ

1 Gutierrez A,Silverman LB.Acute Lymphoblastic leukemia.In:Orkin HS,Fisher DE,Ginsburg D,Look T,Lux SE,Nathan DG,editors.Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood.Philadelphia:Elsevier,2015:1527-1554

2 Carroll WL,BhatlaT.Acute Lymphoblastic leukemia.In:Lanzkowsky P,Lipton JM,Fish JD,editors.Manual of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology.London:Elsevier,2016:367-389

3 Ebert EC,Hagspiel KD.Gastrointestinal manifestations of leukemia.

2012;27:458-463[PMID:21913980 DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06908.x]

4 Segal I,Rassekh SR,Bond MC,Senger C,Schreiber RA.Abnormal liver transaminases and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia at presentation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

2010;55:434-439[PMID:20658613 DOI:10.1002/pbc.22549]

5 Gu RL,Xiang M,Suo J,Yuan J.Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in an adolescent presenting with acute hepatic failure:A case report.

2019;11:135-138[PMID:31316772 DOI:10.3892/mco.2019.1877]

6 Reddi DM,Barbas AS,Castleberry AW,Rege AS,Vikraman DS,Brennan TV,Ravindra KV,Collins BH,Sudan DL,Lagoo AS,Martin AE.Liver transplantation in an adolescent with acute liver failure from acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

2014;18:E57-E63[PMID:24438382 DOI:10.1111/petr.12221]

7 Abaji R,Krajinovic M.Thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphisms in acute lymphoblastic leukemia,inflammatory bowel disease and autoimmune disorders:influence on treatment response.

2017;10:143-156[PMID:28507448 DOI:10.2147/PGPM.S108123]

8 DeLeve LD.Cancer chemotherapy.In:Kaplowitz N,DeLeve LD,editors.Drug-induced liver disease.Amsterdam:Elsevier,2013:541-568

9 Hijiya N,van der Sluis IM.Asparaginase-associated toxicity in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

2016;57:748-757[PMID:26457414 DOI:10.3109/10428194.2015.1101098]

10 Schmiegelow K.Advances in individual prediction of methotrexate toxicity:a review.

2009;146:489-503[PMID:19538530 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07765.x]

11 Rodrigues FG,Dasilva G,Wexner SD.Neutropenic enterocolitis.

2017;23:42-47[PMID:28104979 DOI:10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.42]

12 Altınel E,Yarali N,Isık P,Bay A,Kara A,Tunc B.Typhlitis in acute childhood leukemia.

2012;21:36-39[PMID:22024548 DOI:10.1159/000331587]

13 Robazzi TC,Silva LR,Mendonça N,Barreto JH.Gastrointestinal manifestations as initial presentation of acute leukemias in children and adolescents.

2008;38:126-132[PMID:18697407]

14 Guan X,An X,Yu J,Xu Y.Incidence of upper digestive tract inflammation in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis.

2018;11:3671-3677[PMID:31949748]

15 Cardona Zorrilla AF,Reveiz Herault L,Casasbuenas A,Aponte DM,Ramos PL.Systematic review of case reports concerning adults suffering from neutropenic enterocolitis.

2006;8:31-38[PMID:16632437 DOI:10.1007/s12094-006-0092-y]

16 Tamburrini S,Setola FR,Belfiore MP,Saturnino PP,Della Casa MG,Sarti G,Abete R,Marano I.Ultrasound diagnosis of typhlitis.

2019;22:103-106[PMID:30367357 DOI:10.1007/s40477-018-0333-2]

17 Kirkpatrick ID,Greenberg HM.Gastrointestinal complications in the neutropenic patient:characterization and differentiation with abdominal CT.

2003;226:668-674[PMID:12601214 DOI:10.1148/radiol.2263011932]

18 Mullassery D,Bader A,Battersby AJ,Mohammad Z,Jones EL,Parmar C,Scott R,Pizer BL,Baillie CT.Diagnosis,incidence,and outcomes of suspected typhlitis in oncology patients--experience in a tertiary pediatric surgical center in the United Kingdom.

2009;44:381-385[PMID:19231539 DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.094]

19 Ali A,Alhindi S,Alalwan AA.Acute Appendicitis in a Child With Acute Leukemia and Chemotherapy-Induced Neutropenia:A Case Report and Literature Review.

2020;12:e8858[PMID:32617245 DOI:10.7759/cureus.8858]

20 Lakshmaiah KC,Malabagi AS,Govindbabu,Shetty R,Sinha M,Jayashree RS.Febrile Neutropenia in Hematological Malignancies:Clinical and Microbiological Profile and Outcome in High Risk Patients.

2015;7:116-120[PMID:26417163 DOI:10.4103/0974-2727.163126]

21 Wang Y,Zhang X,Dong L,Tang K,Fang H,Tang Z,Zhang B.Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with pancreas involvement in an adult patient mimicking pancreatic tumor:A case report.

2019;98:e15685[PMID:31169671 DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000015685]

22 Grimes AC,Chen Y,Bansal H,Aguilar C,Perez Prado L,Quezada G,Estrada J,Tomlinson GE.Genetic markers for treatment-related pancreatitis in a cohort of Hispanic children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

2021;29:725-731[PMID:32447501 DOI:10.1007/s00520-020-05530-w]

23 Stefanović M,Jazbec J,Lindgren F,Bulajić M,Löhr M.Acute pancreatitis as a complication of childhood cancer treatment.

2016;5:827-836[PMID:26872431 DOI:10.1002/cam4.649]

24 Raja RA,Schmiegelow K,Frandsen TL.Asparaginase-associated pancreatitis in children.

2012;159:18-27[PMID:22909259 DOI:10.1111/bjh.12016]

25 Bender C,Maese L,Carter-Febres M,Verma A.Clinical Utility of Pegaspargase in Children,Adolescents and Young Adult Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia:A Review.

2021;11:25-40[PMID:33907490 DOI:10.2147/BLCTT.S245210]

26 Youssef YH,Makkeyah SM,Soliman AF,Meky NH.Influence of genetic variants in asparaginase pathway on the susceptibility to asparaginase-related toxicity and patients' outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

2021;88:313-321[PMID:33959786 DOI:10.1007/s00280-021-04290-6]

27 Wolthers BO,Frandsen TL,Baruchel A,Attarbaschi A,Barzilai S,Colombini A,Escherich G,Grell K,Inaba H,Kovacs G,Liang DC,Mateos M,Mondelaers V,Möricke A,Ociepa T,Samarasinghe S,Silverman LB,van der Sluis IM,Stanulla M,Vrooman LM,Yano M,Zapotocka E,Schmiegelow K;Ponte di Legno Toxicity Working Group.Asparaginaseassociated pancreatitis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia:an observational Ponte di Legno Toxicity Working Group study.

2017;18:1238-1248[PMID:28736188 DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30424-2]

28 Berman JN,Look AT.Pediatric Myeloid Leukemia,Myelodysplasia,and Myeloproliferative Disease.In:Orkin HS,Fisher DE,Ginsburg D,Look T,Lux SE,Nathan DG,editors.Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood.Philadelphia:Elsevier,2015:1555-1613

29 Van de Louw A,Lewis AM,Yang Z.Autopsy findings in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era:a focus on lung pathology and acute respiratory failure.

2019;98:119-129[PMID:30218164 DOI:10.1007/s00277-018-3494-3]

30 Walsh LR,Yuan C,Boothe JT,Conway HE,Mindiola-Romero AE,Barrett-Campbell OO,Yerrabothala S,Lansigan F.Acute myeloid leukemia with hepatic infiltration presenting as obstructive jaundice.

2021;15:100251[PMID:34141563 DOI:10.1016/j.lrr.2021.100251]

31 Nakano Y,Yamasaki K,Otsuka Y,Ujiro A,Kawakita R,Tamagawa N,Okada K,Fujisaki H,Yorifuji T,Hara J.Acute Myeloid Leukemia With

Presenting as Severe Hepatic Failure.

2017;4:2333794X16689011[PMID:28239626 DOI:10.1177/2333794X16689011]

32 Athale UH,Kaste SC,Bodner SM,Ribeiro RC.Splenic rupture in children with hematologic malignancies.

2000;88:480-490[PMID:10640983]

33 Vincenzi B,Armento G,Spalato Ceruso M,Catania G,Leakos M,Santini D,Minotti G,Tonini G.Drug-induced hepatotoxicity in cancer patients - implication for treatment.

2016;15:1219-1238[PMID:27232067 DOI:10.1080/14740338.2016.1194824]

34 Trivedi CD,Pitchumoni CS.Drug-induced pancreatitis:an update.

2005;39:709-716[PMID:16082282 DOI:10.1097/01.mcg.0000173929.60115.b4]

35 Kobos R,Shukla N,Armstrong SA.Infant leukemias.In:Orkin HS,Fisher DE,Ginsburg D,Look T,Lux SE,Nathan DG,editors.Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood.Phiadelphia:Elsevier,2015:1614-1625

36 Hang XF,Xin HG,Wang L,Xu WS,Wang JX,Ni W,Cai X,Zhang RQ.Nonleukemic myeloid sarcoma of the liver:a case report and review of literature.

2011;5:747-750[PMID:21484146 DOI:10.1007/s12072-010-9233-z]

37 Bhatnagar N,Nizery L,Tunstall O,Vyas P,Roberts I.Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis and AML in Down Syndrome:an Update.

2016;11:333-341[PMID:27510823 DOI:10.1007/s11899-016-0338-x]

38 Hijiya N,Millot F,Suttorp M.Chronic myeloid leukemia in children:clinical findings,management,and unanswered questions.

2015;62:107-119[PMID:25435115 DOI:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.09.008]

39 Many BT,Lautz TB,Dobrozsi S,Wilkinson KH,Rossoff J,Le-Nguyen A,Dakhallah N,Piche N,Weinschenk W,Cooke-Barker J,Goodhue C,Zamora A,Kim ES,Talbot LJ,Quevedo OG,Murphy AJ,Commander SJ,Tracy ET,Short SS,Meyers RL,Rinehardt HN,Aldrink JH,Heaton TE,Ortiz MV,Baertschiger R,Wong KE,Lapidus-Krol E,Butter A,Davidson J,Stark R,Ramaraj A,Malek M,Mastropolo R,Morgan K,Murphy JT,Janek K,Le HD,Dasgupta R,Lal DR;PEDIATRIC SURGICAL ONCOLOGY RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE.Appendectomy Versus Observation for Appendicitis in Neutropenic Children With Cancer.

2021;147[PMID:33504609 DOI:10.1542/peds.2020-027797]

40 Alexander S,FerrandoAA.Pediatric Lymphoma.In:Orkin HS,Fisher DE,Ginsburg D,Look T,Lux SE,Nathan DG,editors.Nathan and Oski’s Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood.Philadelphia:Elsevier,2015:1626-1672

41 Guermazi A,Brice P,de Kerviler E E,Fermé C,Hennequin C,Meignin V,Frija J.Extranodal Hodgkin disease:spectrum of disease.

2001;21:161-179[PMID:11158651 DOI:10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja02161]

42 Englund A,Glimelius I,Rostgaard K,Smedby KE,Eloranta S,Molin D,Kuusk T,Brown PN,Kamper P,Hjalgrim H,Ljungman G,Hjalgrim LL.Hodgkin lymphoma in children,adolescents and young adults - a comparative study of clinical presentation and treatment outcome.

2018;57:276-282[PMID:28760045 DOI:10.1080/0284186X.2017.1355563]

43 Hagleitner MM,Metzger ML,Flerlage JE,Kelly KM,Voss SD,Kluge R,Kurch L,Cho S,Mauz-Koerholz C,Beishuizen A.Liver involvement in pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma:A systematic review by an international collaboration on Staging Evaluation and Response Criteria Harmonization(SEARCH)for Children,Adolescent,and Young Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma(CAYAHL).

2020;67:e28365[PMID:32491274 DOI:10.1002/pbc.28365]

44 Guliter S,Erdem O,Isik M,Yamac K,Uluoglu O.Cholestatic liver disease with ductopenia(vanishing bile duct syndrome)in Hodgkin's disease:report of a case.

2004;90:517-520[PMID:15656342]

45 Shah KK,Pritt BS,Alexander MP.Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation.

2017;7:1-12[PMID:31723695 DOI:10.1016/j.jctube.2017.02.001]

46 Rich NE,Sanders C,Hughes RS,Fontana RJ,Stravitz RT,Fix O,Han SH,Naugler WE,Zaman A,Lee WM.Malignant infiltration of the liver presenting as acute liver failure.

2015;13:1025-1028[PMID:25277846 DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.040]

47 Shimizu Y.Liver in systemic disease.

2008;14:4111-4119[PMID:18636653 DOI:10.3748/wjg.14.4111]

48 Bakhit M,McCarty TR,Park S,Njei B,Cho M,Karagozian R,Liapakis A.Vanishing bile duct syndrome in Hodgkin's lymphoma:A case report and literature review.

2017;23:366-372[PMID:28127210 DOI:10.3748/wjg.v23.i2.366]

49 Ghosh I,Bakhshi S.Jaundice as a presenting manifestation of pediatric non-Hodgkin lymphoma:etiology,management,and outcome.

2010;32:e131-e135[PMID:20445407 DOI:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181d640c5]

50 Odemiş B,Parlak E,Başar O,Yüksel O,Sahin B.Biliary tract obstruction secondary to malignant lymphoma:experience at a referral center.

2007;52:2323-2332[PMID:17406815 DOI:10.1007/s10620-007-9786-4]

51 Huang MS,Weinstein H.Non-HodgkinsLymphoma.In:Lanzkowsky P,Lipton JM,Fish JD,editors.Manual of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology.London:Elsevier,2016:442-452

52 Cheson BD,Fisher RI,Barrington SF,Cavalli F,Schwartz LH,Zucca E,Lister TA;Alliance,Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group;Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group;European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium;Italian Lymphoma Foundation;European Organisation for Research;Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology Group;Grupo Español de MédulaÓsea;German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group;German Hodgkin's Study Group;Japanese Lymphoma Study Group;Lymphoma Study Association;NCIC Clinical Trials Group;Nordic Lymphoma Study Group;Southwest Oncology Group;United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute.Recommendations for initial evaluation,staging,and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma:the Lugano classification.

2014;32:3059-3068[PMID:25113753 DOI:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800]

53 Superfin D,Iannucci AA,Davies AM.Commentary:Oncologic drugs in patients with organ dysfunction:a summary.

2007;12:1070-1083[PMID:17914077 DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1070]

54 Ballonoff A,Kavanagh B,Nash R,Drabkin H,Trotter J,Costa L,Rabinovitch R.Hodgkin lymphoma-related vanishing bile duct syndrome and idiopathic cholestasis:statistical analysis of all published cases and literature review.

2008;47:962-970[PMID:17906981 DOI:10.1080/02841860701644078]

55 Aftandilian CC,Friedmann AM.Burkitt lymphoma with pancreatic involvement.

2010;32:e338-e340[PMID:20930650 DOI:10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181ed1178]

56 Pietsch JB,Shankar S,Ford C,Johnson JE.Obstructive jaundice secondary to lymphoma in childhood.

2001;36:1792-1795[PMID:11733908 DOI:10.1053/jpsu.2001.28840]

57 Almakdisi T,Massoud S,Makdisi G.Lymphomas and chylous ascites:review of the literature.

2005;10:632-635[PMID:16177287 DOI:10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-632]

58 Bhardwaj R,Vaziri H,Gautam A,Ballesteros E,Karimeddini D,Wu GY.Chylous Ascites:A Review of Pathogenesis,Diagnosis and Treatment.

2018;6:105-113[PMID:29577037 DOI:10.14218/JCTH.2017.00035]

59 Steinemann DC,Dindo D,Clavien PA,Nocito A.Atraumatic chylous ascites:systematic review on symptoms and causes.

2011;212:899-905.e1[PMID:21398159 DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.010]

60 Curakova E,Genadieva-Dimitrova M,Misevski J,Caloska-Ivanova V,Andreevski V,Todorovska B,Isahi U,Trajkovska M,Misevska P,Joksimovic N,Genadieva-Stavric S,Antovic S,Jankulovski N.NonHodgkin's Lymphoma with Peritoneal Localization.

2014;2014:723473[PMID:24711934 DOI:10.1155/2014/723473]

61 Ravindranath A,Srivastava A,Seetharaman J,Pandey R,Sarma MS,Poddar U,Yachha SK.Peritoneal Lymphomatosis Masquerading as Pyoperitoneum in a Teenage Boy.

2019;6:e00116[PMID:31616776 DOI:10.14309/crj.0000000000000116]

62 Biko DM,Anupindi SA,Hernandez A,Kersun L,Bellah R.Childhood Burkitt lymphoma:abdominal and pelvic imaging findings.

2009;192:1304-1315[PMID:19380555 DOI:10.2214/AJR.08.1476]

63 James KM,Bogue CO,Murphy AJ,Navarro OM.Peritoneal Malignancy in Children:A Pictorial Review.

2016;67:402-408[PMID:27523447 DOI:10.1016/j.carj.2016.03.003]

64 Que Y,Wang X.Sonography of peritoneal lymphomatosis:some new and different findings.

2015;31:55-58[PMID:25706365 DOI:10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000085]

65 Ugurluer G,Miller RC,Li Y,Thariat J,Ghadjar P,Schick U,Ozsahin M.Primary Hepatic Lymphoma:A Retrospective,Multicenter Rare Cancer Network Study.

2016;8:6502[PMID:27746888 DOI:10.4081/rt.2016.6502]

66 Delemos AS,Friedman LS.Systemic causes of cholestasis.

2013;17:301-317[PMID:23540504 DOI:10.1016/j.cld.2012.11.001]

67 Citak EC,Sari I,Demirci M,Karakus C,Sahin Y.Primary hepatic Burkitt lymphoma in a child and review of literature.

2011;33:e368-e371[PMID:22042287 DOI:10.1097/MPH.0b013e31822ea131]

68 Baumhoer D,Tzankov A,Dirnhofer S,Tornillo L,Terracciano LM.Patterns of liver infiltration in lymphoproliferative disease.

2008;53:81-90[PMID:18540976 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03069.x]

69 Noronha V,Shafi NQ,Obando JA,Kummar S.Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver.

2005;53:199-207[PMID:15718146 DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.10.010]

70 Cameron AM,Truty J,Truell J,Lassman C,Zimmerman MA,Kelly BS Jr,Farmer DG,Hiatt JR,Ghobrial R,Busuttil RW.Fulminant hepatic failure from primary hepatic lymphoma:successful treatment with orthotopic liver transplantation and chemotherapy.

2005;80:993-996[PMID:16249751 DOI:10.1097/01.tp.0000173999.09381.95]

71 Yabe M,Miranda RN,Medeiros LJ.Hepatosplenic T-cell Lymphoma:a review of clinicopathologic features,pathogenesis,and prognostic factors.

2018;74:5-16[PMID:29337025 DOI:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.01.005]

72 Diak P,Siegel J,La Grenade L,Choi L,Lemery S,McMahon A.Tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers and malignancy in children:forty-eight cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration.

2010;62:2517-2524[PMID:20506368 DOI:10.1002/art.27511]

73 van Rheenen PF,Aloi M,Assa A,Bronsky J,Escher JC,Fagerberg UL,Gasparetto M,Gerasimidis K,Griffiths A,Henderson P,Koletzko S,Kolho KL,Levine A,van Limbergen J,Martin de Carpi FJ,Navas-López VM,Oliva S,de Ridder L,Russell RK,Shouval D,Spinelli A,Turner D,Wilson D,Wine E,Ruemmele FM.The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn's Disease:an ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update.

2020[PMID:33026087 DOI:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa161]

74 Turner D,Ruemmele FM,Orlanski-Meyer E,Griffiths AM,de Carpi JM,Bronsky J,Veres G,Aloi M,Strisciuglio C,Braegger CP,Assa A,Romano C,Hussey S,Stanton M,Pakarinen M,de Ridder L,Katsanos K,Croft N,Navas-López V,Wilson DC,Lawrence S,Russell RK.Management of Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis,Part 1:Ambulatory Care-An Evidence-based Guideline From European Crohn's and Colitis Organization and European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology,Hepatology and Nutrition.

2018;67:257-291[PMID:30044357 DOI:10.1097/MPG.0000000000002035]

75 Kassira N,Pedroso FE,Cheung MC,Koniaris LG,Sola JE.Primary gastrointestinal tract lymphoma in the pediatric patient:review of 265 patients from the SEER registry.

2011;46:1956-1964[PMID:22008334 DOI:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.06.006]

76 Kumar P,Singh A,Deshmukh A,Chandrashekhara SH.Imaging of Bowel Lymphoma:A Pictorial Review.

2021[PMID:33877497 DOI:10.1007/s10620-021-06979-3]

77 Morsi A,Abd El-Ghani Ael-G,El-Shafiey M,Fawzy M,Ismail H,Monir M.Clinico-pathological features and outcome of management of pediatric gastrointestinal lymphoma.