Identifying water vapor sources of precipitation in forest and grassland in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains, Central Asia

CHEN Haiyan, CHEN Yaning, LI Dalong, LI Weihong, YANG Yuhui

1 College of Geography and Environmental Science, Hainan Normal University, Haikou 571158, China;

2 Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Environmental Change of Tropical Islands, Hainan Province, Haikou 571158,China;

3 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China;

4 Xinjiang Normal University, Urumqi 830013, China

Abstract: Identifying water vapor sources in the natural vegetation of the Tianshan Mountains is of significant importance for obtaining greater knowledge about the water cycle, forecasting water resource changes, and dealing with the adverse effects of climate change. In this study, we identified water vapor sources of precipitation and evaluated their effects on precipitation stable isotopes in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains, China. By utilizing the temporal and spatial distributions of precipitation stable isotopes in the forest and grassland regions, Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory(HYSPLIT) model, and isotope mass balance model, we obtained the following results. (1) The Eurasia,Black Sea, and Caspian Sea are the major sources of water vapor. (2) The contribution of surface evaporation to precipitation in forests is lower than that in the grasslands (except in spring), while the contribution of plant transpiration to precipitation in forests (5.35%) is higher than that in grasslands(3.79%) in summer. (3) The underlying surface and temperature are the main factors that affect the contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation; meanwhile, the effects of water vapor sources of precipitation on precipitation stable isotopes are counteracted by other environmental factors. Overall, this work will prove beneficial in quantifying the effect of climate change on local water cycles.

Keywords: Tianshan Mountains; Manas River Basin; water vapor sources of precipitation; land cover; precipitation stable isotopes; Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory

1 Introduction

Tianshan Mountains are considered to be the ‘water tower’ of Central Asia (Quincey et al., 2018).Mid-mountain forests and low-mountain grasslands are the major natural vegetation distributions in this region, which facilitate the formation and conservation of water resources (Farinotti et al.,2015; Chen et al., 2016). Identifying water vapor sources in the forest and grassland regions of the Tianshan Mountains will provide more information about the water cycle, while enabling the forecasting of future water resource changes. However, there is a lack of observation data in the mountain areas (Zhang et al., 2017). As the environmental variables differ significantly in space and time due to the complex terrain, most remote sensing datasets and reanalysis datasets with low spatial resolutions cannot be reliably used in the mountain areas (Tang et al., 2017; Xu et al.,2018). Furthermore, the monitoring data are very scarce due to bad traffic. Thus, the lack of reliable datasets is the major limiting factor for elucidating the water cycle in the region.

A large amount of climatic and hydrological information is recorded in precipitation stable isotopes. They have been widely used in global and regional water cycle studies (Apaéstegui et al.,2018; Gazquez et al., 2018). Modern precipitation isotopes are stable indicators of water vapor sources, phase change, and water vapor transmission paths (Bowen et al., 2018; Vimeux and Risi,2021). Many studies have tried to analyze the water vapor sources of precipitation based on stable isotopes. These studies covered regions with different climates, such as monsoon (Crawford et al.,2013; Rahul et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2020; Zhao and Zhou, 2021), temperate marine climate (Krklec and Dominguez-Villar, 2014; Krklec et al., 2018), and inland arid climate(Kong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; An et al., 2017).

Numerous studies have attempted to obtain more information about water vapor sources of precipitation in the Tianshan Mountains based on precipitation stable isotopes. In the north slope of Tianshan Mountains, the water vapor mainly originates from Eurasia (Wang et al., 2017); the contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation is higher in the bigger oasis (Urumqi Oasis)than that in the smaller oases (Shihezi Oasis and Caijiahu Oasis) (Wang et al., 2016). In the Urumqi River Basin, the temperature and evaporation decrease with an increase in altitude;consequently, the fraction of recycled water vapor in precipitation decreases (Kong et al., 2013).However, a small number of studies have quantified the contribution of different water vapor sources to precipitation in areas with different land covers.

This study utilizes precipitation stable isotopes in forest and grassland regions, the Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model, and isotope mass balance model to identify the water vapor sources, quantify their contribution to precipitation in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains, Central Asia, and discuss the factors that affect the water vapor sources of precipitation.

2 Study area

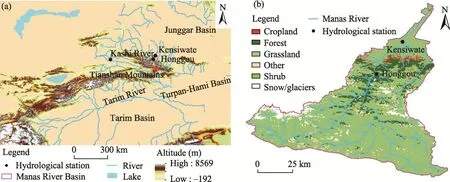

Manas River Basin is situated at the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China. The maximum and minimum altitude is 5131 m and 582 m (above sea level), respectively. Areas with altitudes above 3900 m (the snow line) are covered by permanent snow and glaciers. Overall, there are 726 glaciers that cover an area of 637.8 km2in the basin (Guo et al., 2014). The glaciers are an important recharge source for the Manas River(Chen et al., 2019). From the foot to the top of the mountain, the land cover comprises oases and deserts, desert steppes, upland meadows, spruce forests, alpine meadows, alpine cushion-like vegetation, and lichen (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 (a) Schematic of the study area and hydrological stations used in the study and (b) land cover of the Manas River Basin. Land cover data are from MODIS Land Cover Products (MCD12Q1) (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd12q1v006/).

The area exhibits a typical temperate continental climate with scarce precipitation. The annual mean temperature ranges from 4.7°C to 5.7°C. The mean annual precipitation ranges from 115 mm to 200 mm. The precipitation is mainly concentrated in summer. The altitude of Honggou station(in the forest area) and Kensiwate station (in the grassland area) is 1472 m and 860 m, respectively(Fig. 1). From August 2015 to July 2016, the annual mean temperature, total precipitation, and potential evapotranspiration was 4.0°C, 570 mm, and 866 mm at Honggou station, respectively;the respective values were 6.2°C, 498 mm, and 916 mm at Kensiwate station.

3 Datasets and methods

3.1 Sampling and analysis

All the samples were collected at the above-mentioned hydrological stations (Fig. 1). From August 2015 to July 2016, precipitation and stream water samples were collected at Honggou station and Kensiwate station at the Manas River Basin, and the hydrological station at the Kashi River Basin(43°48′36″N, 81°54′00″E). Honggou station and Kensiwate station are located in the forest and grassland regions of the Manas River Basin, respectively. The Kashi River station is situated at the upwind of the Manas River Basin. At Honggou station, 97 precipitation samples and 295 stream water samples were collected; at Kensiwate station, 119 precipitation samples and 295 stream water samples were collected; and at Kashi River station, 127 precipitation samples and 295 stream water samples were collected. Standard Chinese rain gages with a funnel diameter of 20 cm were used as samplers. Precipitation samples were collected immediately after precipitation events.From March to October, stream water samples were collected at 14:00 (LST) every day. In other months, stream water samples were collected at 14:00 (LST) every three days. More information about sampling and sample analysis can be obtained by Chen et al. (2019) and Chen et al. (2020).

3.2 Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model

HYSPLIT model is a complete system to compute air parcel trajectories and simulate dispersion,chemical transformation, and deposition (Draxier and Hess, 1998; Draxler and Rolph, 2016). In this study, we used the dataset from Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS) (Kleist et al., 2009)with a spatial resolution of 1°×1°. The backward duration was set as 10 d (Wang et al., 2017). The lifting condensation level (LCL) was set as the initial modeling height of the air mass; LCL was generally determined from humidity and temperature data (Berberan-Santos et al., 1997) and varied with each event.

HYSPLIT model is widely used to detect the transportation trajectory of water vapor and dust.However, the traditional HYSPLIT model maintains a constant backward duration and starting height, without considering meteorological variables that can result in the erroneous identification of water vapor sources. It is technically easy to obtain the air mass transportation trajectory 10 d before precipitation. However, it is difficult to precisely determine the time and location at which the moisture significantly recharges into the air mass. The actual moisture recharge could occur in less than 10 d before precipitation. To determine the water vapor source more precisely, we adjusted the transportation trajectory based on specific humidity (Sodemann et al., 2008, Crawford et al., 2013). For each 6 h interval, if the specific humidity of the following time interval increases by more than 0.2 g/kg when compared to that in the previous time interval, the air parcel location at the previous time interval is identified as an evaporative source. In this study, we only modeled the trajectories of Honggou station as the distance between Honggou station and Kensiwate station is less than 1°, although the land cover of these two areas is completely different.

3.3 Isotope mass balance model

The contributions of upwind water vapor, evaporation vapor, and transpiration vapor to precipitation can be quantified via the isotope mass balance model (van der Ent et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016):

whereftr,fev, andfadvdenote the fractions of transpiration, surface evaporation, and advection moisture in precipitation (%), respectively. Additionally,δpv,δtr,δev, andδadvdenote the concentration of stable isotopes in precipitation vapor, transpiration vapor, surface evaporation vapor, and upwind water vapor (‰), respectively. H and O denote the stable hydrogen isotope and stable oxygen isotope, respectively.

The concentration of stable isotopes in precipitation vapor (δpv) is calculated with the following equation (Gibson and Reid, 2014):

whereδpdenotes the concentration of precipitation stable isotope (‰) andkrepresents an adjusting factor. The value ofkranges from 0.5 to 1.0; it equals 0.5 for regions with significant seasonal variation and 1.0 for regions with no significant seasonal variation (Skrzypek et al., 2015;Wang et al., 2016). We takekas 0.5 in this study as the seasonal variation is significant in the study area.ε+denotes the equilibrium fractionation factor between water and water vapor:

whereδsdenotes the concentration of stable isotopes in surface evaporation vapor (‰),hdenotes the relative humidity (%),εdenotes the total fractionation coefficient, andεkdenotes the kinetic fractionation factor.

The concentration of stable isotopes in evaporation vapor (δs) is calculated by following Skrzypek et al. (2015), Gibson et al. (2016), and Diamond and Jack (2018):

The concentration of stable isotopes in upwind water vapor (δadv) is calculated with the Rayleigh fractionation formula:

whereδpv-advdenotes the concentration of stable isotopes in precipitation water vapor from the upwind regions (‰) andFdenotes the residual water fraction of raindrops after evaporation as they fall to the ground (%), which is calculated using precipitation water vapor (Wang et al., 2016).

Under the steady-state condition, the concentrations of stable isotopes in transpiration vapor(δtr) from plants are unfractionated when compared to the source water utilized by the plants; thus,these can be measured using xylem water (Yakir and Sternberg, 2000). In the Manas River Basin,local plants either utilize groundwater or surface water that has been transformed by precipitation and snow/glacier meltwater. Conversely, stream water in the Manas River is a combination of precipitation, snow/glacier meltwater, and baseflow (Chen et al., 2019). In this study, we denoted the concentration of stable isotopes in stream water asδtr.

4 Results and discussion

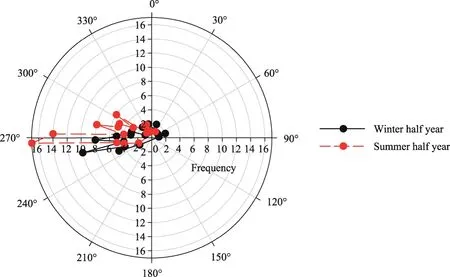

4.1 Transportation trajectory of precipitation water vapor

The air mass mainly originates from the west and northwest, with no significant seasonal variations (Figs. 2 and 3). Based on the air mass transportation trajectory, the precipitation water vapor in the Manas River Basin mainly originates from the following four sites: (1) the Arctic Ocean; (2) the Atlantic Ocean; (3) the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea, and Caspian Sea; and (4) the Eurasia. We also observed few precipitation events wherein the air mass is sourced from the east or the Red Sea and Persian Gulf in the southwest; these events occurred in summer and winter.

Fig. 2 Spatial and temporal distributions of raw and adjust trajectories of Honggou station for each precipitation event in August 2015 to July 2016 in (a) spring, (b) summer, (c) autumn, and (d) winter. The satellite-derived land cover is downloaded from Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com).

After correction of the transportation trajectory based on specific humidity, the length of all trajectories decreased. The precipitation water vapor in the Manas River Basin is mainly derived from the Eurasia, Black Sea, and Caspian Sea. The frequency of precipitation events where water vapor originated directly from the Atlantic Ocean and Arctic Ocean is very low (Fig. 2).

Our results are consistent with those of previous studies; that is, the precipitation water vapor in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains mainly originates from the west and northwest (Dai et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). After adjusting the trajectories, we found that the precipitation water vapor mainly originates from the Eurasia, Black Sea, and Caspian Sea (irrespective of the seasons). Only a few precipitation events occurred in winter and summer, wherein water vapor originated from the north Atlantic and Arctic.However, previous studies have indicated that water vapor sources of precipitation vary significantly with seasons. The water vapor sources of summer precipitation, especially rainstorms, are mainly the north Atlantic and Arctic oceans (Dai et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2017).

There are two major reasons leading to the difference between our results and previous research.First, all precipitation events have been elucidated in our study; however, Dai et al. (2007) and Huang et al. (2017) only researched the rainstorms as the Tianshan Mountains are far away from the ocean and exhibit low air humidity. Precipitation in this region ranges from light to moderate.Second, only the mid-mountain zone covered by grasslands and forests has been considered in our study, whereas Dai et al. (2007) and Huang et al. (2017) studied the entire area of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. The mid-mountain zone is more wet than the plains and basins in Xinjiang, while being a major site for water resource formation and conservation in Central Asia(Farinotti et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2016). Thus, locally evaporated water is an important water vapor source for light to moderate precipitation in the mid-mountain zone.

Fig. 3 Distribution of water vapor sources from different directions at Honggou station during August 2015 to July 2016. Here, the summer half year occurs from April to September, while the winter half year ranges from October to March in the next year.

4.2 Contribution of recycled water vapor

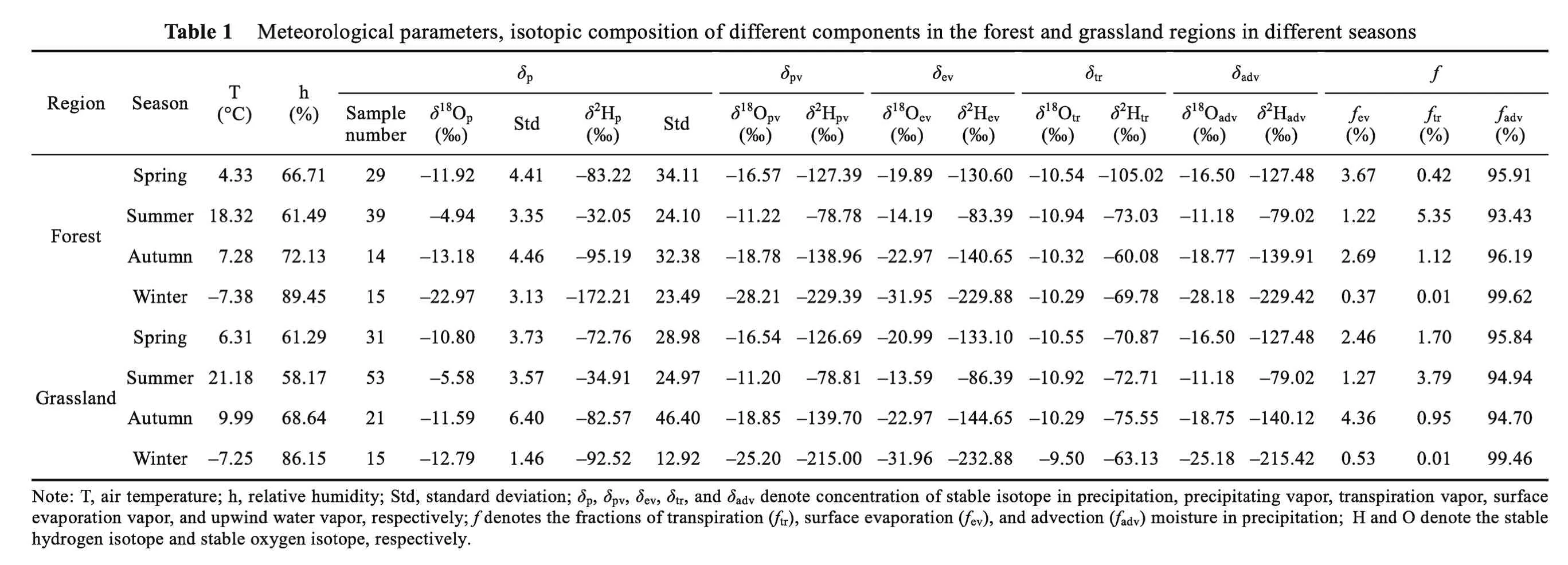

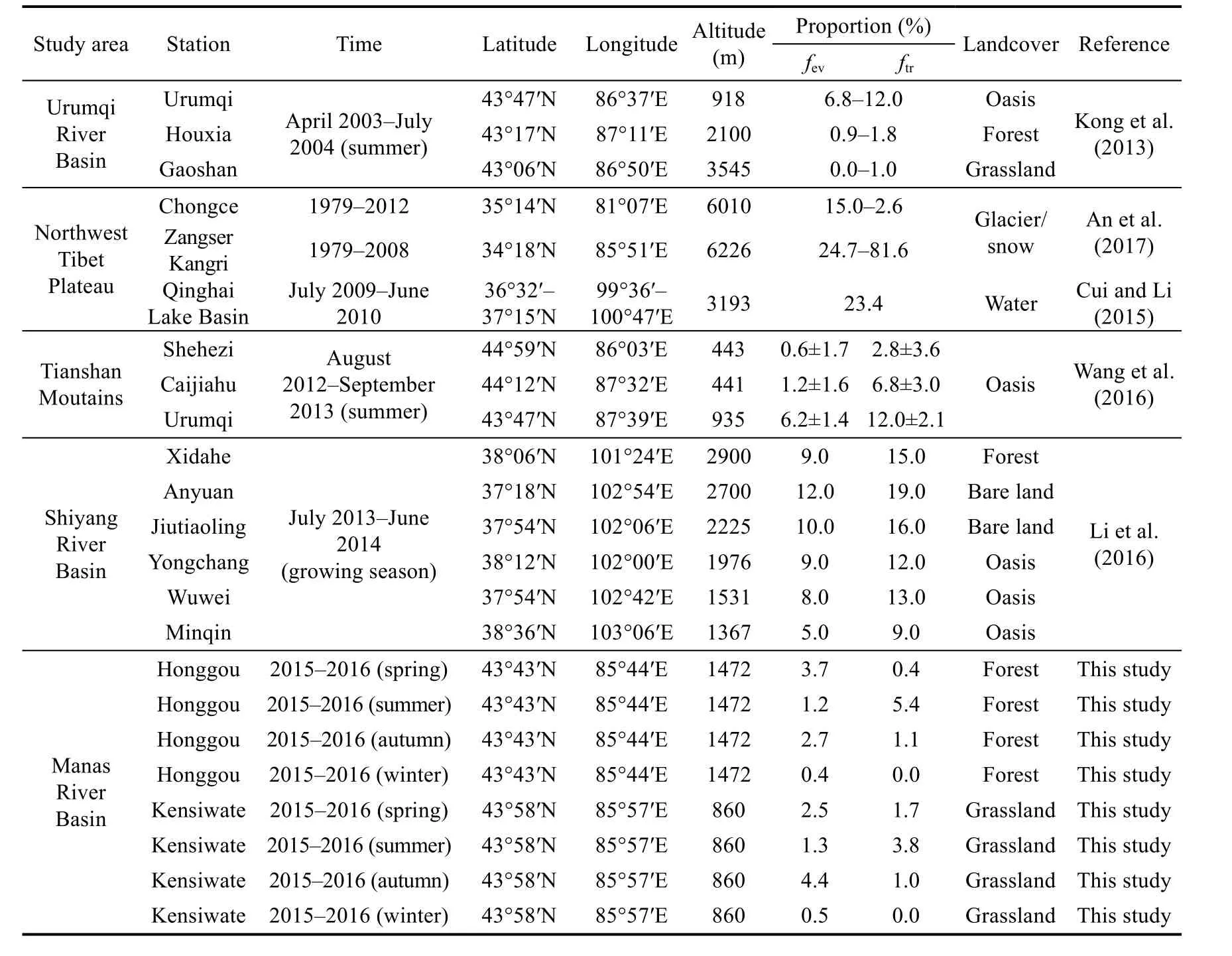

Table 1 shows the contribution of each water vapor source to precipitation in the Manas River Basin. At higher altitudes and lower temperatures, the potential evaporation is lower in forests than that in grasslands. However, the actual evaporation is higher in forests than that in grasslands because snow covers a larger area for a longer duration in forests in spring. The contribution of evaporation water vapor is higher in the forests (3.67%) than that in the grasslands (2.46%).Given the lower altitude and higher temperature in other seasons, evaporation is more intensive in grasslands than that in forests.

Conversely, because of a lower altitude and higher temperature in spring, vegetation exhibits a higher growth in grasslands than that in forest areas; the contribution of transpiration water vapor to overall precipitation in the grasslands (1.70%) exceeds that in forests (0.42%). In winter, the temperature is always lower than 0.00°C, while the plant transpiration is weak in both grasslands and forests. However, in summer and autumn, the plant transpiration is more intensive in forests than that in grasslands, while the contribution of transpiration water vapor is higher in forests(5.35% and 1.12% in summer and autumn, respectively) than that in grasslands (3.79% and 0.95% in summer and autumn, respectively).

?

4.3 Factors affecting the contribution of recycled water vapor

On a global scale, transpiration water vapor from plants constitutes a major part of the recycled water. It almost accounts for 39%±10% of the incident precipitation and 61%±15% of the total land evapotranspiration (Schlesinger and Jasechko, 2014). In the Urumqi River Basin, an increase in altitude causes the land cover to comprise oases, forests, and grasslands at Urumqi station,Houxia station, and Gaoshan station, respectively. The contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation decreases with an increase in the altitude (Kong et al., 2013). In the northwest Tibet Plateau, the contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation increases with a rise in temperature, especially in areas with adequate water for evapotranspiration such as the Qinghai Lake and areas covered by snow and glacier (Cui and Li, 2015; An et al., 2017).

For a similar land cover, the contribution of recycled water vapor increases with altitude and vegetation area/water area. At Shihezi City, Caijiahu Town, and Urumqi City located in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains, the land cover comprises an artificial oasis and the oasis area increases successively. The altitude of the Urumqi oasis (935 m) exceeds that of the Shihezi oasis and the Caijiahu oasis (440 m for both). The contribution of recycled water vapor is the highest in the Urumqi oasis and the lowest in the Shihezi oasis (Wang et al., 2016). In the Shiyang River Basin of China, as the altitude increases, the land cover changes from an artificial oasis to a desert and then to a forest; consequently, the contribution of recycled water increases (Li et al., 2016). In the Manas River Basin, as the altitude increases, the land cover changes from a desert steppe to a forest; the contribution of recycled water vapor increases with a rise in altitude in summer;however, it decreases in other seasons (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of studies on recycled water vapor estimated based on stable water isotopes in Northwest China

4.4 Effect of water vapor source on stable isotopes in precipitation

Water vapor can significantly affect the composition of precipitation stable isotopes (Krklec and Dominguez-Villar, 2014; Jeelani et al., 2018). At Postojna of Slovenia, which is located in Central Europe,δ18O andδ2H values of precipitation water vapor from the continent are lower than those from the ocean. Under the effect of evapotranspiration and post-condensation exchange between raindrops and atmospheric water vapor, there are similarities inδ18O andδ2H values of precipitation water vapor from different oceans (Krklec et al., 2018). In the Sydney Basin of Australia,δ18O value of precipitation is higher for water vapor sourced from the continent as compared to that sourced from the ocean. However, given the effect of sub-cloud evaporation and mixing, the d-excess values of precipitation are similar for continental and oceanic water vapor(Crawford et al., 2013).

Conversely, in the East Asia monsoon region, strong convection in the source region of water vapor and long-distance transport of water vapor tends to reduce the weight of stable isotopes in water vapor and decreaseδ18O value of precipitation (Tang et al., 2015). Given the low relative humidity in the source region of water vapor, non-equilibrium evaporation tends to be intensive in water vapor transportation and results in high d-excess values (Tang et al., 2017). In the Indian Ocean monsoon zone, the water vapor is sourced from ocean in the monsoon season and sourced from the continent in other seasons. The concentration of precipitation stable isotopes is lower in monsoon season than that in other seasons (Breitenbach et al., 2010; Rai et al., 2014; Guo et al.,2017; Jeelani et al., 2018).

For oases in the hinterland of Eurasia located in the north slope of the Tianshan Mountains,increases in the area of the oasis augment the intensity of evaporation and transpiration, expand the fraction of recycled water vapor in precipitation, and decrease the concentration of precipitation stable isotopes (Wang et al., 2016). All the aforementioned studies indicate that the stable isotopes in precipitation change with water vapor source.

However, in the Manas River Basin, no significant relationship between precipitation stable isotopes and the distance of water vapor transport is observed (Figs. 4 and 5). In inland arid areas,which comprise complex water vapor sources and exhibit low relative humidity, the sub-cloud evaporation and exchange between precipitation water vapor and ambient moisture are very intensive. This could counteract the information regarding the water vapor source in precipitation stable isotopes (Balagizi et al., 2018; Krklec et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020). Under the effect of altitude and with increases in contributions of recycled water vapor to precipitation due to the increased intensity of transpiration in forests than in grasslands, the precipitation stable isotopes in the forests are lower than those in grasslands. However, it is difficult to separately quantify the effect of altitude and land cover.

4.5 Uncertainty analysis

Statistical uncertainty and model uncertainty are the two major uncertainty sources that have been used to evaluate the contribution of different water vapor sources to precipitation. Statistical uncertainty is caused by variations in tracer concentrations. Model uncertainty is caused by violations of the underlying assumptions (Delsman et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2018).

With respect to the isotope mass balance model, end-member selection and calculations are the two major source of uncertainty (Joerin et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2015). In this study,δpv,δs,δev,andδadvwere calculated withδpbased on different hypotheses, which are not always tenable in the field. Determining the concentration of stable isotopes in transpiration water vapor (δtr) from plants is another important source of uncertainty. Its basic theory is that under the steady state, the concentrations of stable isotopes in transpiration vapor (δtr) from plants are unfractionated when compared to source water utilized by local plants (Yakir and Sternberg, 2000). There are significant spatial and temporal variations in the source water utilized by plants. Moreover, water isotope monitoring has not been performed consistently to date in the Tianshan Mountains. Data obtained for one year are not sufficient and may lead to loss of information (Chen et al., 2019).

Fig. 4 Relationship between δ18O and back tracking time of precipitation vapor (a and b) and the relationship between d-excess and back tracking time of precipitation vapor (c and d) at Honggou station from August 2015 to July 2016. (a) and (c) denote the summer half year; (b) and (d) denote the winter half year. The boxes represent the 25%-75% percentiles, and the line through the box represents the median (50th percentile). The whiskers indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles, and points above and below the whiskers indicate the 95th and 5th percentiles. Different lowercase letters in the figure indicate the significant differences among the five back tracking times (P<0.05).

Fig. 5 Relationship of moisture transport distance with δ18O (a) and d-excess (b) in precipitation

For HYSPLIT model, the dataset used is one of the most important sources of uncertainty. The resolution of the data used by HYSPLIT model is 1°×1°. Since the Tianshan Mountains exhibit a highly complex terrain, valuable information is smoothed out.

5 Conclusion

Based on the spatial and temporal variations of precipitation stable isotopes in forests and grasslands in the Manas River Basin, we analyzed the water vapor sources of precipitation and quantified the contribution of each water vapor source to precipitation. It is of great importance to accurately forecast the water cycle processes and the local water resource in arid areas under the background of climate change.

The Eurasia, Black Sea, and Caspian Sea are the major water vapor sources of precipitation in the basin. Significant seasonal changes in the contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation are observed. In spring, the contribution of evaporation water vapor is higher in forests than that in grasslands. In summer, the contribution of transpiration water vapor is higher in the forests(5.35%) than that in grasslands (3.79%). Land cover and temperature are the major factors affecting the contribution of recycled water vapor to precipitation. Furthermore, the water vapor sources of precipitation do not have a significant effect on the precipitation stable isotopes.

Although water stable isotopes can offer more hydrological information regarding the past,present, and future changes in the water cycle of arid areas, high-range monitoring is needed in the future.

Acknowledgement

The research is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province, China(420QN258) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41630859, 41761004).

- Journal of Arid Land的其它文章

- Spatiotemporal changes of eco-environmental quality based on remote sensing-based ecological index in the Hotan Oasis, Xinjiang

- Ecosystem service values of gardens in the Yellow River Basin, China

- Adjustment of precipitation measurements using Total Rain weighing Sensor (TRwS) gauges in the cryospheric hydrometeorology observation (CHOICE)system of the Qilian Mountains, Northwest China

- Effects of climate change and land use/cover change on the volume of the Qinghai Lake in China

- Effects of vegetation near-soil-surface factors on runoff and sediment reduction in typical grasslands on the Loess Plateau, China