Applications of endoscopic ultrasound elastography in pancreatic diseases: From literature to real life

Clara Benedetta Conti, Giacomo Mulinacci, Raffaele Salerno,Marco Emilio Dinelli, Roberto Grassia

Abstract Elastography is a non-invasive method widely used to measure the stiffness of the tissues, and it is available in most endoscopic ultrasound machines, using either qualitative or quantitative techniques. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography is a tool that should be applied to obtain a complementary evaluation of pancreatic diseases, together with other imaging tests and clinical data. Elastography can be informative, especially when studying pancreatic masses and help the clinician in the differential diagnosis between benign or malignant lesions. However, further studies are necessary to standardize the method, increase the reproducibility and establish definitive cut-offs to distinguish between benign and malignant pancreatic masses. Moreover, even if promising, elastography still provides little information in the evaluation of benign conditions.

Key Words: Elastography; Pancreas; Pancreatic stiffness; Pancreatitis; Pancreatic cancer;Endosonography; Endoscopic ultrasound; Quantitative elastography; Strain elastography;Pancreatic diseases

INTRODUCTION

Elastography is a non-invasive method used to measure the stiffness of different tissues[1,2].

Nowadays, it is widely used in various medical fields, and it is available in most endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) machines as an integrated software. EUS stiffness measurement can be assessed using either a qualitative or a quantitative method.

Qualitative elastography

The qualitative technique, known as strain elastography, is a method based on the use of a colored scale:red-green areas indicate softer tissues, whereas blue areas indicate stiffer tissues. This type of measurement is useful but does not allow a quantitative measurement. Its clinical application is simple and intuitive, and this explains its large use. However, since the interpretation of different colors and images is largely operator dependent, it lacks reproducibility. Thus, it provides little information when comparing different patients, lesions, or diffuse diseases[3,4].

Semi-quantitative and quantitative elastography

Semi-quantitative analysis allows a numeric measurement of the tissue stiffness by using both the strain ratio (SR) and the strain histogram technique.

When using the SR, the operator sets a bigger region of interest (ROI), usually a circle or a square, on the target tissue (i.e.a lesion) and a smaller ROI above a reference tissue, usually a homogeneous soft area. The SR is calculated by dividing the stiffness data of the two regions, expressed either by the speed wave through the tissues (m/s) or converted to the Young’s modulus (kPa)[5]. This technique is largely used in the evaluation of pancreatic lesions, where the reference tissue is the normal pancreas. However,despite its quantitative nature, this analysis only allows partial information of the tissue, without giving the mean and median stiffness values of the lesion.

Conversely, the strain histogram method generates an average hue histogram that graphically represents the colors and therefore the stiffness distribution within the tissue. The mean value of the histogram can thus be considered a good esteem of the real elasticity of the target[6,7]. This method can be more informative when facing a large tissue, such as a diffuse pancreatic disease, as it collects the stiffness of different areas and gives the operator a unique average value.

EUS shear wave measurement (SWM) allows a quantitative measurement of the stiffness, and it can be expressed in either m/s or in kPa[5]. This method provides a numeric value, usually a mean and a median value of the tissue stiffness. This technique is theoretically more informative than the semiquantitative one, as it simplifies a comparison between individuals or diseases. The final value can be obtained by a single measurement or by calculating the mean and median value of repeated measurements. The operator sets the ROI within the target tissue or lesion and obtains several values through the repetition of the measurement, usually five or ten. Successively, the mean and median measurement value can be calculated. Hence, a more accurate stiffness assessment is provided[3,8,9].Overall, the best image quality can be achieved when the lesion of interest covers up to 50% of the ROI[10]. This method, largely used in United States machines, is rarely available in EUS machines.

The large application of EUS elastography in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases is relatively new.Moreover, its use in routine practice lacks a high diagnostic accuracy, especially due to the large use of the qualitative method. Accounting for the poor reproducibility and the absence of definitive diagnostic cut-offs, the chance to standardize the method is low. Therefore, the use and the interpretation of elastography in pancreatic diseases are still challenging for clinicians.

This review aims to describe the main applications of EUS elastography in pancreatic diseases, its practical value, and its main limitations.

We performed an accurate literature search using the following MESH terms: “Pancreas;” “pancreatitis;” “chronic pancreatitis;” “acute pancreatitis;” “pancreatic cancer;” “pancreatic lesion;”“elastography;” “elastography AND pancreas;” “pancreatic stiffness;” “endoscopic ultrasound;” “EUS AND elastography;” “ultrasonography AND elastography;” “quantitative elastography AND pancreatitis;” “elastography AND pancreatic cancer;” “autoimmune pancreatitis;” “elastography AND acute pancreatitis;” “focal autoimmune pancreatitis AND diagnosis;” “inflammatory pancreatic masses;”“elastography AND cancer;” and “NET AND elastography.” We identified all the pertinent articles(reviews, original articles, and meta-analyses) published between 2000 and 2021 with an available abstract and/or full text. The reference lists from the selected studies were examined to identify further relevant reports. Only English language papers were included. The level of evidence and strength of recommendations were graded according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine system as of the March 2009 update (http://www.cebm. net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levelsevidence-march-2009).

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF EUS ELASTOGRAPHY IN PANCREATIC DISEASES

Application of elastography in benign pancreatic diseases

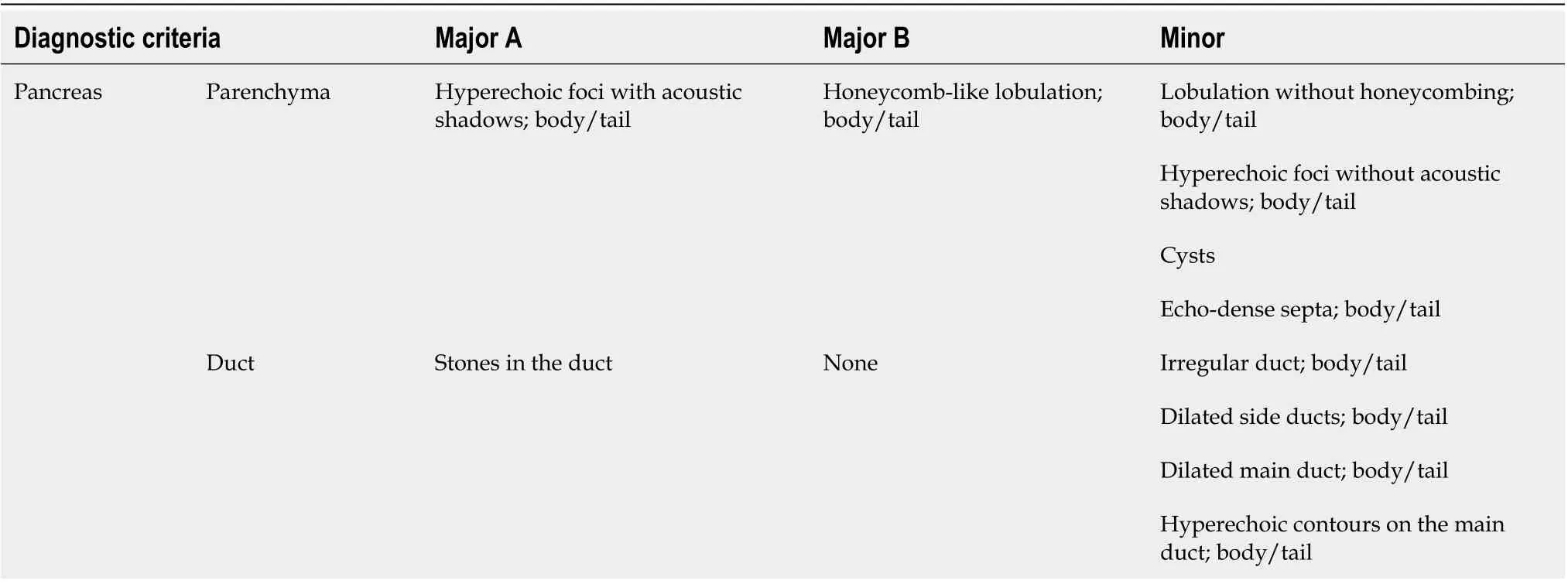

Chronic pancreatitis:The application of qualitative elastography in cases of chronic pancreatitis (CP)conventionally shows a predominantly green pattern with heterogeneous small red or blue areas[11](Figure 1). Even if the colored scale adds more information to the B-mode imaging, it is still not pathognomonic for any specific disorder. Semi-quantitative elastography, using histogram or shear waves, aids the interpretation of the elastography data. This technique was used to retrospectively examine 96 patients with either diagnosed or suspected CP. Each patient was classified using Rosemont criteria (Table 1)[12], and elastography values were significantly different for each stage (P< 0.001)[13].

Similarly, another study measured pancreatic stiffness (PS) in 84 patients and revealed a significantly positive correlation with the Rosemont classification stage (rs = 0.54) and the number of EUS features (rs= 0.47). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for the accuracy of SWMelastography (consistent with CP and suggestive for CPvsnormal and indeterminate for CP) was 0.77(sensitivity 77.1%, specificity 64.9%)[14]. In a multivariate linear regression, hyperechoic foci with shadowing and lobularity with honeycombing were independent features related to PS[10,11].

This data was confirmed by a prospective study with 191 patients, of which 92 were diagnosed with CP. A significant linear correlation was confirmed between the number of EUS criteria of CP and the SR(r= 0.813;P< 0.0001), with an AUROC of 0.949 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.916-0.982]. The accuracy of EUS-elastography for diagnosing CP was 91.1% (cut-off SR of 2.25), and the SR varied significantly among different Rosemont classification groups (P< 0.001)[15]. Another study measured PS in both pancreatic tumors and healthy surrounding parenchyma of 58 consecutive patients before pancreatectomy. Histological fibrosis was divided into four stages: normal, mild, marked, and severe fibrosis.Using the mean PS value, the AUROC for the diagnosis of each fibrosis stage was 0.90[16]. These findings support the theory of PS measurement as a possible surrogate marker for pancreatic fibrosis.

Moreover, a study evaluated 40 patients who underwent pancreatic EUS-SWM. They were classified following the Japan Pancreatic Society criteria for CP. They compared EUS-SWM values of the healthy pancreas with early, probable, and definite CP groups. Notably, the relationship between EUS-SWM value and exocrine/endocrine dysfunction was also assessed. A positive correlation resulted between PS values measured through EUS-SWM and the Japan Pancreatic Society criteria stages, with higher values registered in the CP group. AUROCs for the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-SW measurement for CP, exocrine dysfunction, and endocrine dysfunction were 0.92, 0.78, and 0.63, respectively. The cut-off values of 1.96, 1.96, and 2.34 for diagnosing CP, exocrine dysfunction, and endocrine dysfunctions had a sensitivity of 83%, 90%, and 75% and a specificity of 100%, 65%, and 64%, respectively[17]. Similar results were found by Domínguez-Muñozet al[18]. In the final analysis, elastography seems a promising approach in the evaluation of pancreatitis, even if diagnostic cut-offs are still lacking. Further, large scale studies are awaited to improve the diagnostic accuracy.

Autoimmune pancreatitis:Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a rare condition, even if it is likely underdiagnosed. There is a wide spectrum of radiological features of AIP, from a normal pancreas to diffuse parenchymal enlargement or focal mass-like lesion. The latter radiological appearance is recognized as focal AIP, and it can be easily confused with pancreatic cancer (PC). Thus, it is important to avoid unnecessary surgeries. A correct diagnosis can be reached through the assessment of clinical,laboratory, and histocytological data combined with the EUS evaluation and the assessment of Rosemont Criteria (Table 1). Of note, elastography may help the clinician to differentiate AIP from PC.Indeed, the former usually shows a homogeneous increase of stiffness in the whole organ, while in the latter the increased stiffness is limited within the tumoral area[19]. When using qualitative elastography in AIP, the inflamed area should have a predominantly green pattern with slight red or yellow lines,while a homogeneous green pattern should appear in the normal parenchyma[11]. However, since this does not always occur, the clinician should not completely rely on this pattern presentation to reach thediagnosis.

Table 1 Rosemont criteria for chronic pancreatitis[12]

Figure 1 Quantitative endoscopic ultrasound elastography of chronic pancreatitis. A: Endoscopic ultrasound B-mode with region of interest square;B: Elastographic image.

The quantitative elastography could theoretically be more informative to diagnose AIP. As such, a study measured the stiffness of 123 lesions (78 PC cases and 45 focal AIP cases), and the SR between the lesion and the surrounding parenchyma correlated significantly with the actual presence of a malignancy[20]. Similarly, in a prospective study of 325 patients assessing the SR lesion/parenchyma, a cut-off value of 4.2vs10.9 correlated to sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of 95%, 63%, 89%, 81%, and 87%, respectivelyvs75%, 88%, 95%, 54%,and 79%, respectively[21].

Moreover, in a meta-analysis that included 17 studies (1544 lesions), the pooled sensitivity and specificity for qualitative elastography in the differential diagnosis between PC and AIP were 0.97(95%CI: 0.95-0.99) and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.59-0.74), respectively; the pooled sensitivity and specificity for SR were 0.98 (95%CI: 0.96-0.99) and 0.62 (95%CI: 0.56-0.68), respectively. Interestingly, quantitative elastography has been investigated to assess AIP activity in a small series of patients under steroid therapy[22]. A significant decrease of the mean share wave elastography of the pancreas (P= 0.023) was found. Nevertheless, no definitive cut-offs are available either to diagnose AIP and to distinguish between focal AIP and PC.

Therefore, elastography does not represent the main tool to diagnose AIP, and even though helpful, it is not a crucial test in the differential diagnosis between PC and focal AIP. However, its simple application coupled with serial imaging examinations and fine needle biopsies could help clinicians reach a correct diagnosis[19].

Acute pancreatitis:The application of PS in the evaluation of acute pancreatitis is scarce. Unfortunately,up to now no significant data are available in the literature to help the clinician either in the diagnosis or in the stratification of the severity of the condition.

Application of elastography in the evaluation of malignant diseases

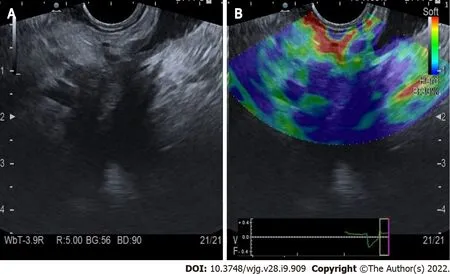

Evaluation of PC:Qualitative elastography applied on the pancreatic focal lesions usually shows a geographic appearance, characterized by a heterogeneous, predominantly blue pattern with small green and red areas (Figure 2). A more homogeneous blue pattern is more typical in pancreatic neuroendocrine malignant tumors[11] (Figure 3). Even if not pathognomonic, these findings can be helpful, in particular when there is a clear demarcation from the healthy pancreatic parenchyma, which is usually of a homogenous green color.

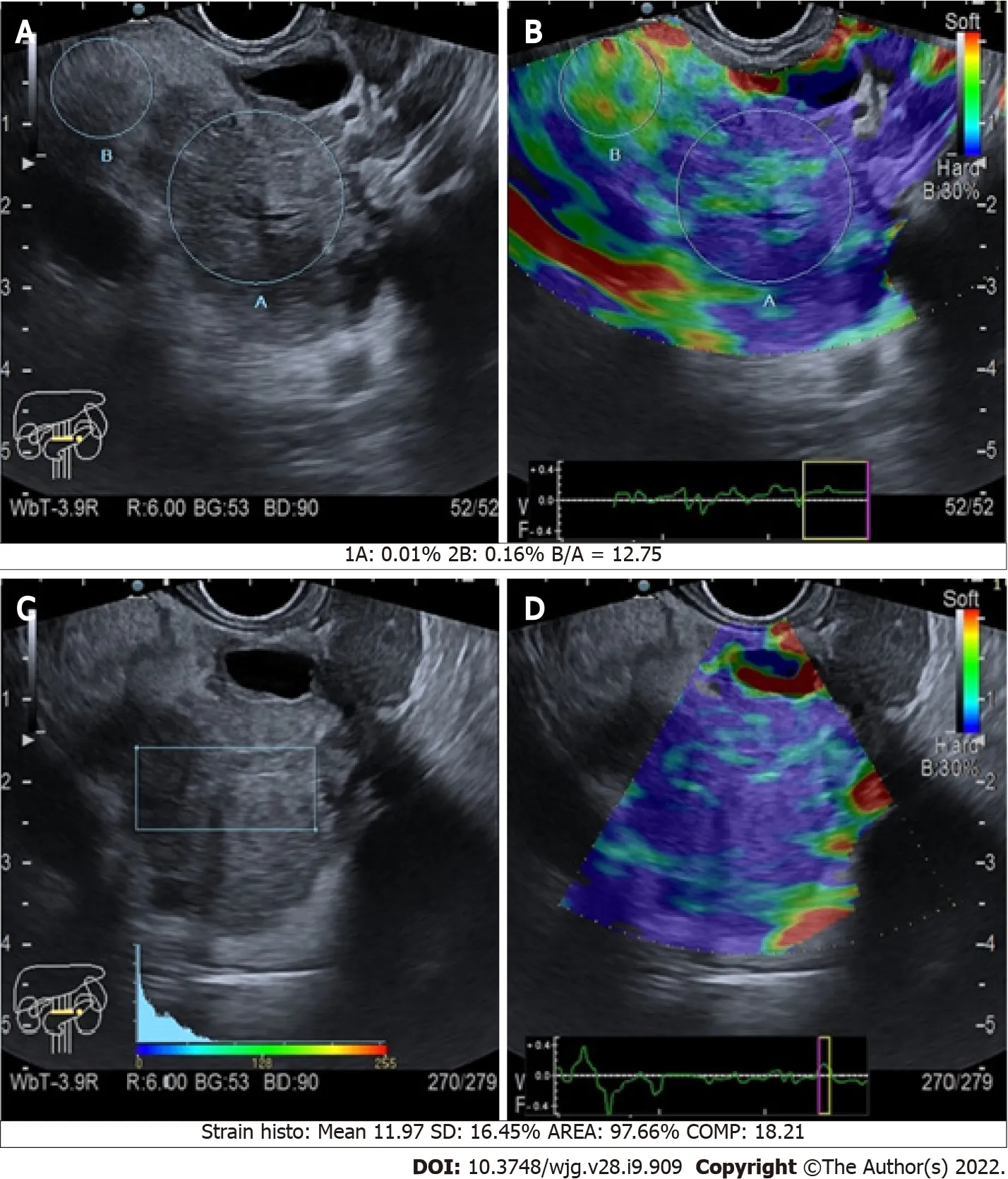

The quantitative assessment is apparently much more informative, as it allows the clinician to compare the SR of a mass over the normal surrounding pancreatic parenchyma (Figure 4). Malignant pancreatic masses show a higher SR than the normal parenchyma[23]. However, it seems that no significant difference exists between the accuracy of quantitative and qualitative methods. In a metaanalysis including 10 studies and 893 pancreatic masses (646 malignant, 72.3%), the positive and negative likelihood ratios were 3.15 and 0.03 for qualitative EUS elastography, and 3.94 and 0.05 for quantitative EUS elastography, respectively[24]. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were useful for excluding the presence of PC, but they had a poor diagnostic specificity[24].

Similar results were found in another meta-analysis[25] involving 1044 patients, in which the pooled sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic odds ratio of EUS elastography to distinguish benign from malignant solid pancreatic masses were 0.95 (95%CI: 0.94-0.97), 0.67 (95%CI: 0.61-0.73), and 42.28(95%CI: 26.90-66.46), respectively. The AUROC was 0.9046[26]. Another meta-analysis involving 17 studies (1544 lesions) showed a pooled sensitivity and specificity for qualitative methods of 0.97 (95%CI:0.95-0.99) and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.59-0.74), respectively[27]. The pooled sensitivity and specificity for strain histograms were 0.97 (95%CI: 0.95-0.98) and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.61-0.73), and the pooled sensitivity and specificity for SR were 0.98 (95%CI: 0.96-0.99) and 0.62 (95%CI: 0.56-0.68). Furthermore, they investigated the pooled sensitivity and specificity for contrast enhancement EUS, which were 0.90 (95%CI:0.83-0.95) and 0.76 (95%CI: 0.67-0.84), respectively. To complete, they analyzed the pooled sensitivity and specificity for EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA), which were 0.84 (95%CI: 0.77-0.90) and 0.96(95%CI: 0.88-1.00), respectively[27].

Overall, data available in the scientific literature show that the sensitivity of elastography for the diagnosis of PC ranges between 92% to 98%. Despite this observation, the specificity is low, as it varies between 67% and 76%[25-27]. Nevertheless, elastography combined with contrast EUS and FNA is likely to increase the diagnostic accuracy for PC detection[28].

Considering the epidemiological relevance of the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) among all the pancreatic lesions, the biggest diagnostic effort when facing a pancreatic mass is directed to exclude it (Figure 4). The definition of elastography cut-offs to distinguish PDAC from other types of pancreatic tumors would be of extreme importance. Nevertheless, no definitive cut-offs are available,even if some studies tried to compare different types of pancreatic lesions.

A study included different types of pancreatic solid lesions: 49 PDAC, 27 inflammatory masses, 6 pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, two metastatic cell lung cancers, one pancreatic lymphoma, and one pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumor. The authors compared these lesions with 20 controls. The mean SRs were: 1.68 (95%CI: 1.59-1.78) for normal pancreatic tissue, 3.28 for inflammatory masses, and 18.12 for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, the highest mean SR was found among neuroendocrine malignant tumors (52.34)[29]. Conversely, in a group of 218 patients with small lesions (23%PDAC, 52% neuroendocrine malignant tumors, 8% metastases, 17% other entities; 66% benign lesions),the high stiffness of the lesion for the diagnosis of malignancy had a sensitivity of 84% (95%CI: 73%-91%), a specificity of 67% (58%-74%), positive predictive value of 56% (50%-62%), and negative predictive value of 89% (83%-93%). For the diagnosis of PDAC, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were 96% (87%-100%), 64% (56%-71%), 45% (40%-50%),and 98% (93%-100%), respectively. In a group of neuroendocrine neoplasms, 64% had a soft pattern on elastography[30].

Targeted biopsy:Another role of EUS elastography can be the detection of pancreatic areas of increased stiffness within a focal lesion to better target the needle during EUS-FNA or fine needle biopsy. To achieve this aim, the application of qualitative elastography can be considered. Indeed, it allows the clinician to examine the lesion, giving the possibility to the operator to perform the needle insertion in the most suitable region, which usually is the hardest part (the softer is often necrotic tissue)[31].Overall, the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-elastography guided FNA is good, with diagnostic accuracy,sensitivity, and specificity for the diagnosis of malignancy of 94%, 93%, and 100%, respectively[32]. No large studies that compare EUS-FNA/fine needle biopsy with and without elastography guide are available. Thus, this use of elastography remains possible but not mandatory.

Figure 2 Qualitative endoscopic ultrasound elastography of pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the head. A: Endoscopic ultrasound B-mode; B:Elastographic image.

Figure 3 Qualitative endoscopic ultrasound elastography of a neuroendocrine malignant tumor of the pancreatic tail. A: Endoscopic ultrasound B-mode; B: Elastographic image.

CONCLUSION

EUS elastography is a technically simple, widely available, risk-free, and cheap exam. Thus, its use should be implemented and encouraged. Among its possible roles, EUS elastography helps the clinicians to add some information to the EUS study of pancreatic diseases, either benign or malignant.Elastography should therefore be considered a complementary tool to B-mode imaging. Notwithstanding its potential, clinicians must be aware that the current application of elastography still has little information[13-16], in particular for concerns of pancreatic diffuse benign diseases[11,15-18]. A potential application of this technique would be the ability to non-invasively stratify patients according to different risk categories for developing PC, similarly to the application of elastography in liver diseases[31]. However, so far, no definitive cut-offs have been recognized for the recognition of benign diseases through elastography. One of the main limitations to standardize the PS application is the lack of corresponding histologic samples as a reference standard, both from the healthy pancreas and pancreatic diseases. This happens because performing a pancreatic biopsy in cases of benign conditions would be unethical and risky.

Figure 4 Quantitative endoscopic ultrasound elastography of pancreatic cancers of the body. A and C: B-mode with region of interest circles and square; B and D: Elastographic images.

Conversely, the use of elastography in the study of solid pancreatic lesions seems to be more informative[25-29], thanks to its high negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PC[22-25]. In particular, soft focal solid pancreatic lesions are rarely PDACs, whereas stiff lesions might be malignant or benign[30].

This makes elastography a fair test to exclude the presence of cancer. Moreover, the combination of elastography with FNA and contrast enhanced EUS could improve the accuracy of the diagnosis, even if no definitive data are available[32].

Nevertheless, it should also be highlighted that elastography cannot be considered mandatory during EUS examination of the pancreas, and there are no data supporting a higher diagnostic accuracy for the endosonographers that routinely use elastographyvswho do not use this method. This latter consideration is mainly supported by the low reproducibility of pancreatic elastography, especially for the qualitative methods[25-28]. One of the major limitations in the use of elastography is the lack of a standardization of the technique. Moreover, the large use of EUS-FNA/fine needle biopsy has increased the accuracy of the diagnosis of PC, and in the case of inadequate sampling or negative cytology/histology, elastography does not have any key role[33]. Summarizing, EUS-related elastography is a tool that should be considered to obtain a complementary evaluation of pancreatic diseases, together with the other imaging tests and clinical data. Elastography can be informative, especially when studying pancreatic masses and help the clinician in the diagnosis. However, further studies are necessary to first standardize the method, increase the reproducibility and establish definitive cut-offs to distinguish between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Conti CB and Grassia R conceived the idea of the manuscript and supervised the findings of the work; Conti CB and Mulinacci G performed the literature search and wrote the draft of the paper with input from all authors; Salerno R and Dinelli ME verified the methods and the contents; Salerno R and Grassia R provided the illustrations by performing the examinations; All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:Clara Benedetta Conti, Giacomo Mulinacci, Raffaele Salerno, Marco Emilio Dinelli, and Roberto Grassia have no conflict of interest.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Italy

ORCID number:Clara Benedetta Conti 0000-0001-9774-2374; Giacomo Mulinacci 0000-0002-9398-893X; Raffaele Salerno 0000-0001-9201-7755; Marco Emilio Dinelli 0000-0003-0214-0333; Roberto Grassia 0000-0003-4491-4050.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年9期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年9期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Radiomics-clinical nomogram for response to chemotherapy in synchronous liver metastasis of colorectal cancer: Good, but not good enough

- Relationship between clinical remission of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease and serum adalimumab concentrations: A multi-center cross-sectional study

- Postoperative morbidity adversely impacts oncological prognosis after curative resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma

- Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator prevents ischemia/reperfusion induced intestinal apoptosis via inhibiting PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway

- Dualistic role of platelets in living donor liver transplantation: Are they harmful?