Relation between skeletal muscle volume and prognosis in rectal cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy

INTRODUCTION

Recently, the influence of anthropometry on treatment outcome has been a matter of research in several fields of surgical oncology. Several reports identified a significant association between specific profiles of the fat and muscular compartments and shortand long-term prognosis in cancer patients.

The most investigated hallmark sign of anthropometric frailty is sarcopenia, which has been identified as a predictor of poor outcome in different gastrointestinal cancers[1-3]. Sarcopenia, initially defined as an age-related reduction in muscle mass and strength, has been otherwise associated with various chronic diseases, including cancer-related malnutrition and cachexia[4-6]. It has been suggested that it may reflect a state of increased metabolic activity of tumor biology leading to host immune functional impairment, deficient response to systemic inflammation, nutritional changes, and altered endocrine function[4,7]. These conditions enhance patient vulnerability towards stressors and lead to an increased risk of developing adverse health outcomes. Actually, skeletal muscle depletion, that is the central feature of sarcopenia,has been negatively associated with chemotherapy toxicity, complications following surgery, and impaired survival in cancer patients[8-11].

Who are you? said Browny, starting up in great fright, for though the voice sounded gentle, he felt sure it was a feigned13 voice, and he feared it was the fox.

The prognostic role of body composition indexes, and specifically sarcopenia, has been broadly explored also in patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection[12-14].Nevertheless, colonic and rectal cancers are often appraised as a single entity despite their substantial differences in surgical management, oncological strategies, and prognosis. Rectal surgery accounts for a considerably greater number of postoperative complications[15,16] and rectal tumors have a higher recurrence rate and a shorter survival than colonic ones[17-19]. In addition, preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NCRT) is the standard care for patients with advanced lower rectal cancer because of the relatively high risk of local recurrence[20]. Accordingly, it would be worthwhile to study more homogeneous patient cohorts.

She rang the bell, and scarcely had she touched it before she found herself in a chamber2 where a bed stood ready made for her, which was as pretty as anyone could wish to sleep in

The identification of patients with skeletal muscle wasting might be critical for early and tailored nutritional interventional planning that may improve long-term outcomes and treatment tolerance as reported in cases of advanced rectal cancer[21]. Thus, we conducted a review to assess whether sarcopenia could be used to predict recurrence and survival among patients with advanced lower rectal cancers who are treated with NCRT followed by surgery.

LITERATURE SEARCH AND STUDIES SELECTION

27. Barred the door: Before the common use of door knobs and intricate locks, doors were often secured by placing large pieces of wood or metal, usually in the shape of a bar, across the door. These bars were often heavy and difficult for a small child to lift, especially with the stealth needed in this situation.Return to place in story.

In the multivariate model, sarcopenia pre-NCRT[23,28,29], or post-NCRT[22,24],was associated with OS. Additionally, in the study by Park[28], sarcopenia was the only independent poor prognostic factor for OS. The DFS was also affected, in the studies by Park[28] and Takeda[29], by sarcopenia before NCRT. Takeda[29] identified that pathological tumor stage and sarcopenia were independently associated with poor OS and DFS in multivariate analysis. Chung[24] identified 51 pts (54.8%) with sarcopenia after the completion of NCRT, while they did not report the absolute number of patients with sarcopenia pre-NCRT. While there was no significant difference in OS or DFS between patients with and without sarcopenia pre-NCRT, in the patients with sarcopenia post-NCRT, the 5-year OS rate was significantly lower with respect to patients without sarcopenia.

Studies were selected if they were related to adult patients with advanced non metastatic rectal cancer at diagnosis who underwent NCRT (any scheme) and surgery with curative intent, and if muscle mass was measured (either preoperatively and/or before and/or after NCRT) and/or change in muscle mass during NCRT was measured, and related to survival.

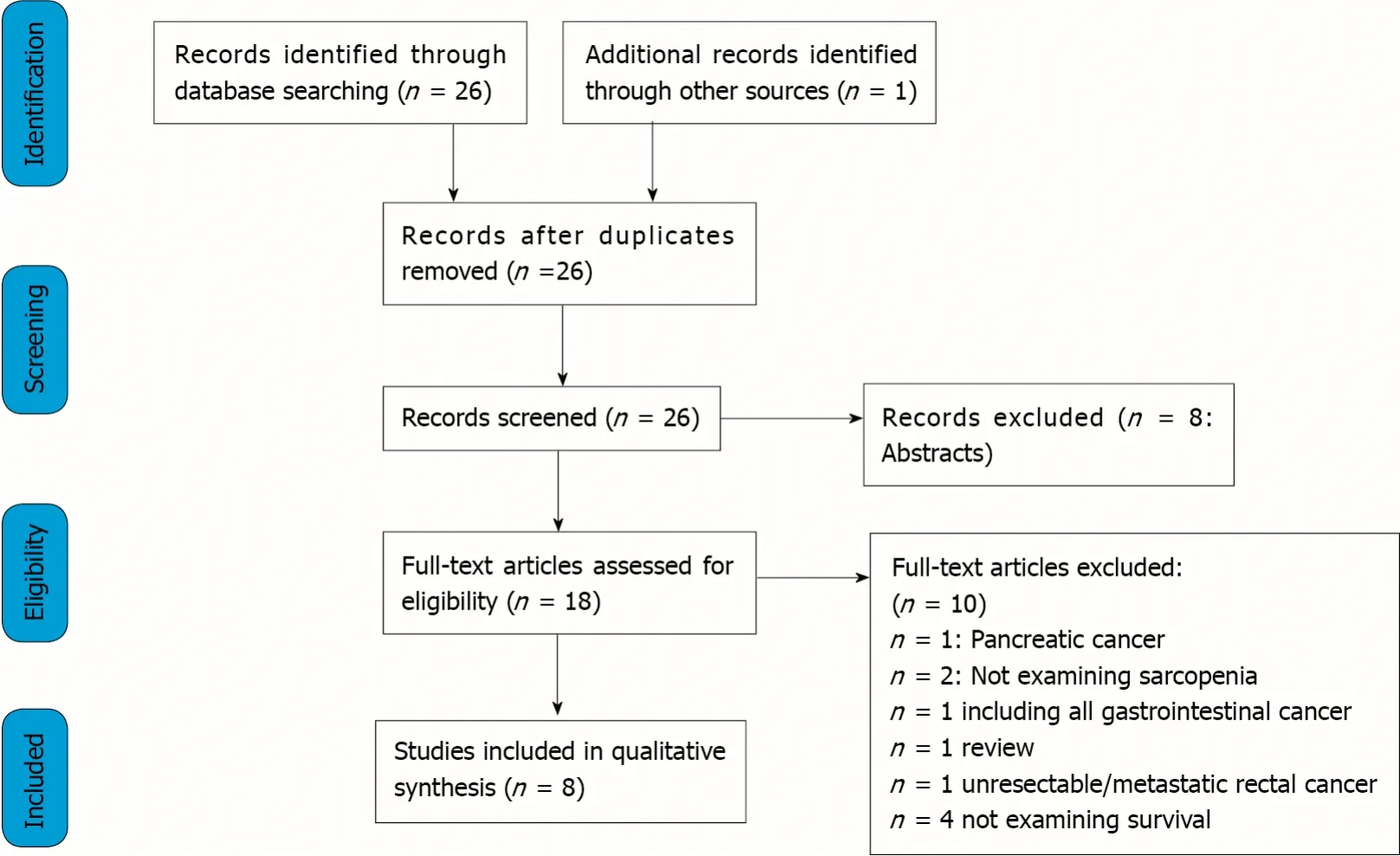

Through databases and reference lists searching, 27 articles were identified. After excluding reviews, abstracts, duplicates, and studies not providing the selected outcome measures, 8 full-text articles were selected and included in the present review[22-29].

A PRISMA flowchart reporting the studies selection process is shown in Figure 1.

STUDY CHARACTERISTICS

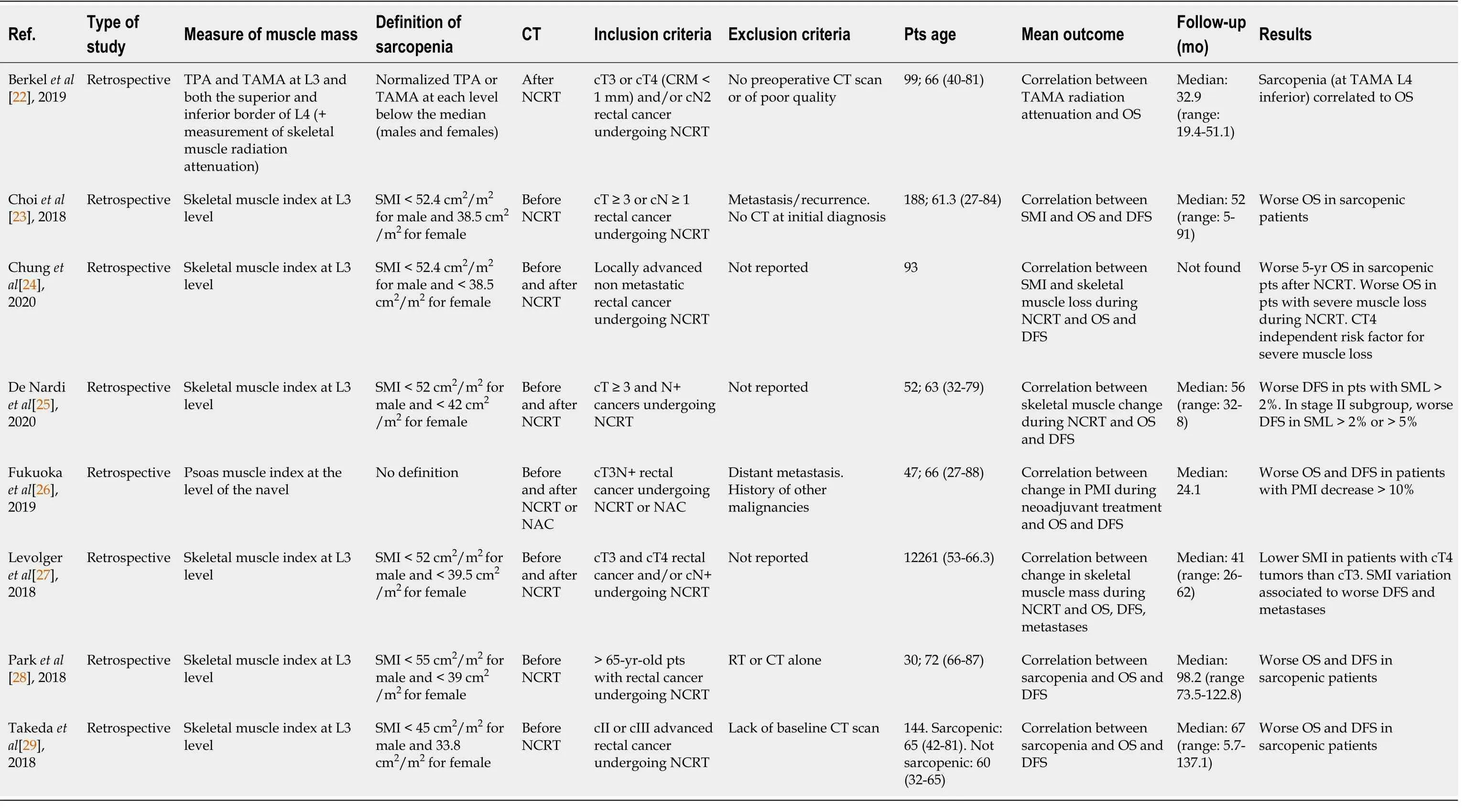

Table 1 summarizes the studies included in this review along with the main outcome measures. All the studies were retrospective, with sample sizes ranging from 30 to 188;all were published between 2017 and 2019 with a median follow-up between 24.1 and 98.2 mo.

DEFINITION OF SARCOPENIA

Irwin Rosenberg defined sarcopenia (from Greek ‘sarx’ or flesh + ‘penia’ or loss) for the first time in 1989 as an age associated decline in skeletal muscle mass[30].However, it was not until 2010 that a Sarcopenia Working Group (SWG) developed a broadly accepted clinical definition and diagnostic criteria that would be used both in clinical practice and in research studies[31]. According to the SWG, sarcopenia was defined as a “syndrome characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength with a risk of adverse outcomes”. The working group also categorized sarcopenia into primary, in which aging is the only apparent cause and secondary, among which different diseases, such as malignancy, play an important role.

The studies examining the rate of change in muscle mass during NCRT also employed different methods; De Nardi[25] established a 2% and 5% variation threshold[25]. Fukuoka[26] employed a 10% threshold, after subtracting the pre-PMI from the post-PMI and then dividing the results by the pre-PMI multiplied by 100. Chung[24] initially calculated (SMI_post-SMI_pre)/SMI_pre × 100 and then dichotomized the patients based on cut-off values of 4.2%/100 d; this process accounted for differences in the time elapsed between the 2 CT scans[24].

In conclusion, although the majority of the authors agreed on the tool and site to measure muscle mass, more research is needed to provide reference values in order to increase the comparability of the results.

The role of sarcopenia in colorectal cancer patients’ postoperative outcomes have been the topic of several works. Sarcopenia independently predicted mortality adjusted for age, sex, and previous abdominal surgery in a study on 310 patients[7]. In another study, Lieffers[8] reported that sarcopenic patients had significantly longer hospitalization and a higher wound infection rate[8]. A systematic review of 12 studies, including 5337 patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer undergoing surgery, confirmed that sarcopenia was not only an independent predictor of postoperative complications, but it was also related to overall, relapse-free and progression-free survival[46]. More recently, another systematic review[47] included 44 randomized and observational studies comprising 18891 patients, to assess the prognostic value of sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes and survival rates of patients with colorectal cancer; studies involving treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer were excluded. Among the 44 studies, twenty-five, with a total of 15446 patients, reported overall survival (OS) as an outcome; the meta-analysis demonstrated an association between sarcopenia and shorter OS; furthermore,sarcopenia was negatively related to disease free survival (DFS) and cancer specific survival. However, when patients with rectal cancer were retrieved from the whole population, the authors could not find a worse survival in sarcopenic patients. Overall,6511 patients had rectal cancer, among them a large proportion had stage I or II and the minority with advanced or metastatic disease, accordingly, only a small proportion of them underwent NCRT.

As a matter of fact, the majority of the studies evaluating the association of sarcopenia and clinical outcome defined sarcopenia as muscle mass alone over muscle strength or physical performance, possibly because it is based on more objective parameters that can be evaluated retrospectively in studies and rely on imaging tools that are widely used in clinical practice. On the contrary, other tests are more subjective, based on patient’s perception, or too long to be administered and thus less suited for research. All the eight studies selected for the present review used muscle mass alone as the diagnostic criterion to define sarcopenia and none employed muscle strength or physical performance.

MEASURE OF MUSCLE MASS

Body muscle mass can be assessed by different techniques including imaging techniques,.Body imaging techniques comprise computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging, and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; CT is the most frequently used in clinical practice for its high accuracy and reproducibility[33]. The problem of the radiation exposure is bypassed in cancer patients because this exam is routinely performed for cancer staging and follow-up. As a substitute of muscle mass, the abdominal wall musculature is the most commonly assessed:Skeletal muscle cross sectional area (cm) is generally measured with CT images at the level of the 3lumbar vertebra (L3). L3 vertebra level is the site most commonly used because it correlates significantly with whole-body muscle[34]. However, there could be differences depending on the exact site of measurement such as the upper, mid, or lower vertebral body. The parameter is then normalized for patient stature and designated as skeletal muscle index, skeletal muscle index (SMI) (cm/m). There was a substantial agreement for the choice of L3 as a reference site and only one study[22] evaluated three levels:The third lumbar vertebra and both the superior and inferior border of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Differently, Fukuoka[26] measured the psoas muscle index (PMI) at the level of the navel as an indicator of skeletal muscle mass; however,this approach is less standardized and since psoas is a minor muscle, it is questioned if it is representative of the overall lean body mass. The threshold of skeletal muscle radiation attenuation, to discriminate between skeletal muscle and other tissues, (mean Hounsfield Units, HU) was −29 to +150 HU[35]. The most common definition of sarcopenia in the studies considered in the present review takes into consideration gender specific cut off values, however these values vary considerably:Cut-off points of 43 cm/m, 52.4 cm/m, 52 cm/m, 49 cm/mfor men, and 41 cm/m, 38.5 cm/m, 42 cm/m, 31 cm/mfor women are reported. Other authors[29] stratified by quartiles according to the SMI values for men and women and defined low skeletal muscle mass as the lowest quartile. A recent review found 12 different diagnostic thresholds for sarcopenia, the most common being 52.4 cm/mfor men and 38.5 cm/mfor women[36], therefore the need for further standardization is highlighted. The cut-off values may differ for different reasons:First for the reference population since,for instance, the Eastern population may have different body size with respect to the Western one[37]. The different threshold may lead to different prevalence of sarcopenia and thus to different results; moreover, it makes it difficult to compare the results of different studies. Interestingly, only one author[22] evaluated the quality of muscle assessing the skeletal muscle radiation attenuation (as mean HU of Total Abdominal Muscle Area, TAMA); according to previous studies, a lower HU corresponded to fatty infiltration of muscle myosteatosis.

My mother s sister is named Katie, Robbie began slowly. She fell in love with Chip. Chip would always send Katie white hyacinths for Easter. He d get the bulbs from Holland and grow them himself in his garden. When they bloomed, he d dig them up, put them in a pot, and give them to her.

The original definition was updated 10 years later as “a progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder that is associated with increased likelihood of adverse outcomes”[32]. One of the main insights of the revision was the prominent role of muscle strength over muscle mass as a measure that better predicts adverse outcomes.This revision also defined these two criteria:(1) Low muscle mass; and (2) Low muscle strength.

Soon afterwards the King s daughter fell into a severe illness. She was his only child, and he wept day and night, so that he began to lose the sight of his eyes, and he caused it to be made known that whosoever rescued her from death should be her husband and inherit the crown. When the physician came to the sick girl s bed, he saw Death by her feet. He ought to have remembered the warning given by his godfather, but he was so infatuated by the great beauty13 of the King s daughter, and the happiness of becoming her husband, that he flung all thought to the winds. He did not see that Death was casting angry glances on him, that he was raising his hand in the air, and threatening him with his withered fist. He raised up the sick girl, and placed her head where her feet had lain. Then he gave her some of the herb, and instantly her cheeks flushed red, and life stirred afresh in her.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SARCOPENIA AND OTHER DEMOGRAPHIC AND/OR PROGNOSTIC FACTORS BEFORE AND AFTER NCRT

Sarcopenia has multiple contributing factors such as age, heritability, diet, nutritional status, lifestyle, chronic diseases, hormonal changes and drug treatments. Low skeletal muscle mass is common among cancer patients. Cancer is a main cause of secondary sarcopenia because of the catabolic state caused by inflammatory reaction, possibly associated with poor nutritional status. As underlined by a recent systematic review,sarcopenia prevalence ranges from 15% to 74% in oncologic patients before cancer treatment[38]. This wide range in prevalence is partly due to different characteristics of tumor; albeit a variation in the definition of sarcopenia, as already stated, may also play a role. Among patients with colorectal cancer, a study on 3262 patients examining medical and demographic characteristics associated with sarcopenia found a prevalence of 42% with a strong correlation to older age, Caucasian race, and advanced disease stage[39]. Several other authors tried to identify patients’ characteristics or tumor factors that could be associated with sarcopenia. As expected, a relationship with older age was found since cancer and aging recognize a similar pathophysiologic mechanism[40]. In patients with colorectal cancer, sarcopenia was associated with body mass index (BMI), serum carcinoembryonic antigen level and mean number of metastatic lymph nodes[10] while in patients with colorectal liver metastasis with female sex, low BMI and a lower amount of intra-abdominal fat[41].

Several of the studies examined in the present review did not explore these correlations[22,25,28] while others[26,27] found no differences in patient demographic and clinical characteristics between sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic patients. On the other hand, an association with BMI was described by 3 studies[23,24,29] and with older age by 2[23,29]. Black[42] reported the data on 86 patients with colorectal cancer and although the results pertaining to rectal cancer patients only cannot be extrapolated,they described an association between sarcopenia and older age and elevated neutrophil count[42]. This last parameter reflects the systemic inflammatory response specific of cancer patients. This association has been demonstrated to be also strongly related to survival in colorectal cancer patients[43]. Interestingly, few studies recognized a relationship between sarcopenia and disease stage[44]; a possible explanation relies in the small sample size of the majority of the studies. In the studies examined here, this difference could not be found due to the homogeneity of tumor stage (only II and III stage rectal cancer). In the study by Levolger[27] no association was found at baseline while, after NCRT, patients with cT4 tumors had a lower SMI when compared to patients with cT3 tumors. Finally, De Nardi[25]examined a subgroup of patients with stage II cancer and found that poor differentiated tumors (G3) were associated with skeletal muscle loss during NCRT[25].

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SARCOPENIA AND SURVIVAL AND DISEASEFREE SURVIVAL

Body composition and functional status in cancer patients have been acknowledged as prominent factors associated with prognosis in different tumors such as liver, rectum,esophagus, stomach and kidney[38]. In patients undergoing surgery, pre-operative sarcopenia has been shown to be an independent unfavorable predicting factor for several cancers and it has been associated with worse clinical outcomes in terms of post-operative complications, hospital stay, morbidity, mortality and a lower tolerance of chemo radiation therapy[45].

A literature review was performed through Medline/PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane library databases until January 2021. Searched terms were:“Rectal cancer” OR “rectal neoplasm” and “sarcopenia” OR “muscle mass” and“neoadjuvant therapy” as term and related Medical Subject Headings. Reference lists of the selected publications were searched for identifying additional studies. Only articles in English language were included.

These two criteria are requested to define sarcopenia and help to resolve several questions concerning diagnostic measures and cut-off points important to clinical practice.

In order to analyze a more homogeneous group of patients in terms of tumor location, stage, and treatments, we restricted our review to patients with advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant NRCT and curative surgery. In the studies analyzing the relation between skeletal muscle depletion and prognosis, we focused on two issues. Firstly, related to single time point measurement of sarcopenia and secondly to the changes in muscle mass during cancer treatment.

In univariate analysis, the majority of the authors reported an association between pre-or post-NCRT sarcopenia and OS[22-24], or both OS and DSF[28,29].

So he paid his bill, and bought a horse with the money that remained, and when the evening came he mounted his horse and stood in front of the inn door, determined22 to stay there all night

In summary, a paucity of studies has examined, up to now, the relation between muscle depletion and prognosis in the group of patients with rectal cancer undergoing NCRT and surgery. Although several of them reported a correlation, particularly with OS, the results are inconsistent so far. The discrepancy among the studies could be due to different definitions of sarcopenia, different time points for performing CT scan, or insufficient power calculation for the analysis. Nevertheless, some interesting reports should encourage clinicians to undertake clinical trials to obtain more robust evidence.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SKELETAL MUSCLE MASS CHANGE DURING NRCT AND SURVIVAL AND DISEASE-FREE SURVIVAL

The existing literature on sarcopenia and prognosis in cancer patients is mainly connected to evaluation of muscle mass at a single time point, while temporal changes of body composition during treatment and their impact on survival have been scarcely studied. Actually, anthropometry is generally assessed only before starting surgical or oncological programs, while a proper appraisal of changes in fat and lean body mass during therapies may be another critical prognostic tool and add value to existing literature.

Some studies demonstrated the negative impact of muscle loss during oncological treatments on prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. Nonetheless, most of those studies occurred in patients with metastatic diseases undergoing palliative chemotherapy. Miyamoto[48] evaluated the association between progressive skeletal muscle loss and prognosis in patients with unresectable colorectal cancer undergoing systemic first-line chemotherapy. It was found that patients who had a loss greater than 5% during chemotherapy experienced significantly shorter progression-free survival than those in the non–skeletal-muscle loss group. Similarly, a decrease in muscle area during chemotherapy of 9% or more was significantly associated with worse OS rates in metastatic colorectal cancer patients in a study by Blauwhoff-Buskermolen[49]. Interestingly, the static pre-treatment evaluation of skeletal muscle depletion was not a risk factor for survival in both cohorts. These results confirmed the value of depletion of skeletal muscle during chemotherapy as a prognostic factor already observed in other diseases[50,51].

Now they had stumbled into a den1 of murderers, and twelve murderers arrived in the dark, intending to kill the strangers and rob them. But before doing so they sat down to supper, and the innkeeper and the witch sat down with them. Together they ate a dish of soup into which they had cut up the raven meat. They had scarcely swallowed a few bites when they all fell down dead, for the raven had passed on to them the poison from the horsemeat.

Heus[52] measured an overall increase in skeletal muscle during neoadjuvant therapy as if chemo-radiation could lessen the inflammatory tumor state and consequently increase muscle mass.

From a biological point of view, the available data suggest that sarcopenia may reflect the increased metabolic activity of a more aggressive tumor leading to systemic inflammation and causing muscle loss. In this perspective, it might be speculated that the modification in body composition could be an expression of a different biologic response to antineoplastic therapy; thus, achieving tumor control with effective chemotherapy has the potential to reverse the catabolic processes causing cachexia. On the contrary, a significant loss of skeletal muscle during treatment suggests a more aggressive disease and potential ineffectiveness of chemotherapy.

Less evidence is available regarding changes in lean body mass specifically during neoadjuvant therapies for rectal cancer. Levolger[27] found that skeletal muscle loss during NCRT was associated with poor DFS and a higher risk of developing distant metastasis; however, muscle depletion did not impair OS. In addition, in their population, single time point assessment of sarcopenia, a widely adopted method was not predictive of survival. In an analogous study[25], NCRT was associated with loss of skeletal muscle in 36.5% of patients, while no variation or increased muscle mass was found in 63.5%. Muscle loss after NCRT was related to worse DFS. Additionally,even if not statistically significant, patients that experienced muscle mass depletion were more likely to have none or a poor response to neoadjuvant treatment. This last evidence, if confirmed, may support the above-mentioned theory of a relationship between treatment failure and muscle depletion. Chung[24] reported that 24.7% of the patients had severe muscle loss after NCRT; they found no difference in survival in sarcopenic patients, before or after NCRT, however patients with severe muscle loss during NCRT showed significant worse OS with respect to the control group. The authors also tried to identify variables that could predict severe muscle loss and found that cT4 tumors were the only risk factor. Finally, Fukuoka[26] reported that a >10% decrease of muscle mass during NCRT was associated with a shorter OS and DFS[26].

Beautiful female slaves,29 dressed in silk and gold, stepped forward and sang before the prince and his royal parents: one sang better than all the others, and the prince clapped his hands30 and smiled at her

Based on the little available evidence, it is not clear if an aggressive tumor biology rather than NCRTis more likely to be the causative factor inducing a critical catabolic state in certain patients. Further studies are needed to define the potential prognostic role of body composition changes during neoadjuvant treatments on pathological tumor response and long-term outcomes. Additionally, despite mounting evidence demonstrating a sarcopenia relationship with poor survival, it is still undefined whether targeted physical and nutritional interventions, aimed at halting or reversing cancer related muscle wasting, may improve the outcomes. Whether these regimens are effective remains to be answered, however, eventually the interval between NCRT and surgery might display a perfect opportunity to enhance the overall condition of locally advanced rectal cancer patients.

CONCLUSION

Only a few studies have been published so far on the relationship between muscle mass and prognosis in rectal cancer patients undergoing NCRT followed by surgery.Overall, these studies demonstrated an association between sarcopenia and OS; in addition, the evaluation of temporal changes in muscle mass during NCRT also showed that muscle loss during treatment was associated with a worse prognosis.Consequently, it is of paramount importance to identify patients with skeletal muscle wasting in order to plan an early and tailored intervention that may improve longterm outcomes.

Jurgen s foster parents went there, and he also went with them fromthe dunes, over heath and moor, where the Skjaerumaa takes itscourse through green meadows and contains many eels; mother eelslive there with their daughters, who are caught and eaten up by wickedpeople

Besides implementing studies examining the relationship between muscle wasting and prognosis, it would be desirable to lead studies evaluating the relationship between sarcopenia and other prognostic factors such as tumor downstaging or complete pathological response.

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2022年2期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2022年2期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology的其它文章

- Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation of solid pancreatic lesions:A systematic review of early outcomes with pooled analysis

- Prevention of late complications of endoscopic resection of colorectal lesions with a coverage agent:Current status of gastrointestinal endoscopy

- Predictive value of serum alpha-fetoprotein for tumor regression after preoperative chemotherapy for rectal cancer

- Chemotherapy predictors and a time-dependent chemotherapy effect in metastatic esophageal cancer

- Association and prognostic significance of alpha-L-fucosidase-1 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- Comprehensive molecular characterization and identification of prognostic signature in stomach adenocarcinoma on the basis of energy-metabolism-related genes