Forgotten Lives in a Leprosy Colony

A filmmaker chronicles life in one of China’s last remaining villages for patients with leprosy

最后的麻風村

As told by Chen YanÜ (陈亚女)

Photographs from the documentary “The Last Leaf”

My name is Chen Yanü, and I’m a documentary filmmaker. I made a documentary about China’s leprosy villages.

There are several leprosy villages in Guangdong province, but I didn’t know much about them. In my second year of college, I had to make a documentary for a class assignment. Our group happened to see a Weibo post about a leprosy village in Guangdong. I had to do a lot of searching before I found that its residents had once been quarantined there.

I thought, “Why don’t they leave?” and went into filming with curiosity.

My journey had a lot of twists and turns the first time I went: First an hour-long bus ride from campus, then a taxi, and then I had to walk a long distance on a dirt road. I lost my way after walking for a while, but luckily there were some people working in the fields nearby. I asked one of the men, and he said the “old lepers” were right up ahead.

It was raining, and I was a mess by the time I got there. My shoes were soaked and covered in mud. The village was surrounded by mountains on all four sides. There were two or three rows of houses, which were residences, as well as some old buildings and some vegetable gardens nearby. That was about it.

One of the most common long-term effects of leprosy is deformation of the limbs, eventually requiring amputation. In more serious cases, there may also be facial deformation. The patients might lose their eyes, or their mouths become warped; it’s horrible. My first impression was that the residents of this village were a grim bunch, quite lonely and miserable—people who had been abandoned by society.

Leprosy is caused by a slow-growing bacteria, and it can strike a person at any age.

At the outset, pale pink patches appear on the skin, and hands or other affected parts gradually become numb. If you pinch someone with leprosy in these areas, they feel no pain. The disease is not deadly, but it can severely disable the limbs or lead to facial deformities. Because the afflicted can infect others, and because their appearances become quite scary, people—even relatives—viewed them as monsters.

Leprosy has a long history in our country. It’s said that Confucius’ disciple Ran Geng contracted the disease toward the end of the Spring and Autumn period.

Back in the early 1950s, there was still no effective treatment or vaccine for leprosy. The only thing they could do was isolate those who fell ill.

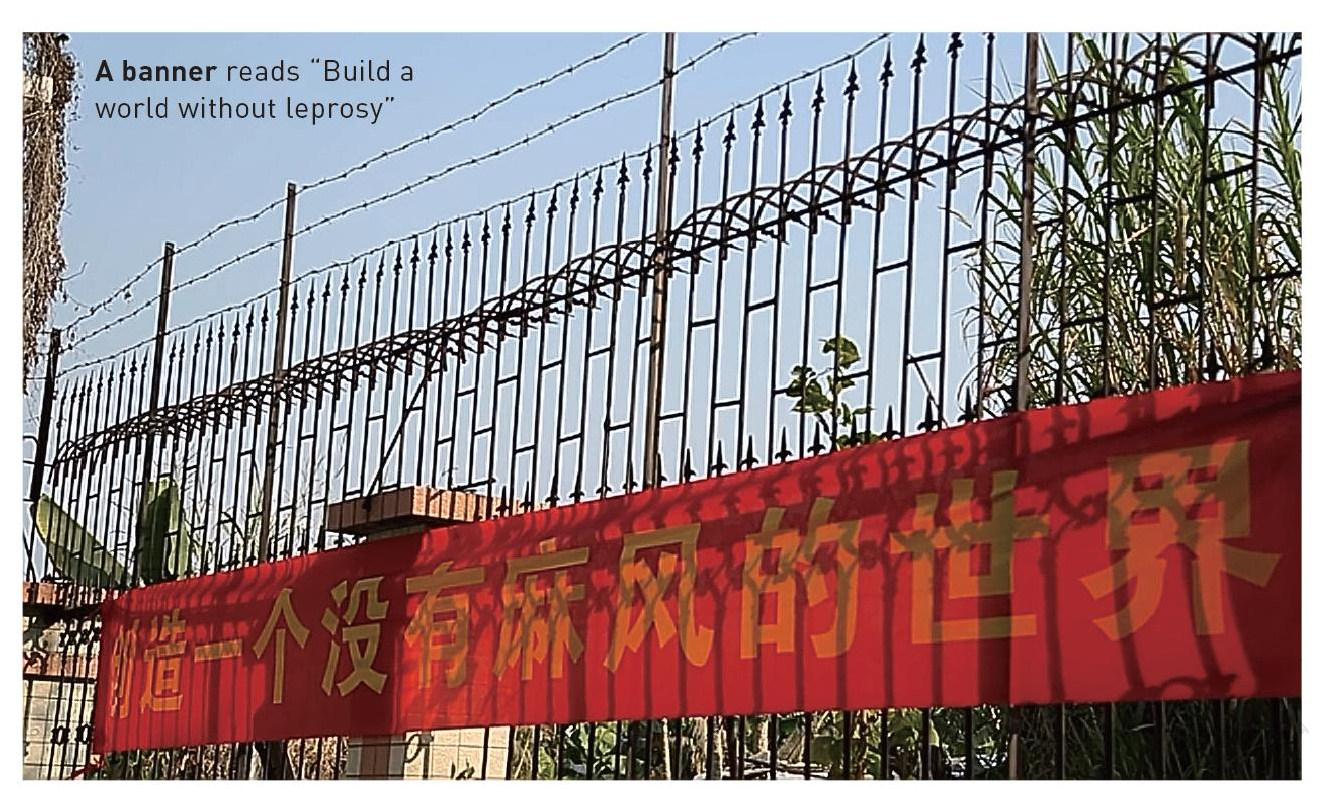

In 1957, China announced its “National Plan for the Prevention and Cure of Leprosy,” quarantining patients in leprosy villages. Doctors went from village to village, conducting an extensive census. Later, over 600 leprosy villages were built, and over 90 percent of the affected population was quarantined.

Most of these villages were built deep in the mountains or on remote islands. They weren’t actually built to treat the afflicted, but to isolate them, preventing them from going out and infecting others. The small hospital in the mountain village I filmed had around 400 patients at its peak, but only five or six doctors and rudimentary facilities.

One man with leprosy told me that when his foot started rotting, he had to take care of himself. Since leprosy causes ulcers, and sufferers often lose feeling in their limbs, they might not even realize their flesh is rotting. Once decay sets in, they have to amputate, because otherwise an infection might become deadly []. There weren’t any prosthetics available—they’d have to buy a piece of steel and make a crude prosthetic for themselves.

Some people contracted leprosy when they were young, showing symptoms by the time they’re a few years old and entering the hospital in their teens. Once they’re inside, they might have remained there for the rest of their lives.

Those who’ve been in the villages since they were young are often more accepting of their situation. But there are people who were in their 30s, married with kids, and had already been living in mainstream society for a long time when the disease suddenly struck. Being sent to a place like this meant totally leaving their previous social networks.

There’s a woman named Zhang Haonü who got sick when she was 34, came to the village at 35, and never left again.

Previously, she was an ordinary peasant woman, with her share of adversity. Her husband worked on a boat, and had been having an affair before she got sick. He often wouldn’t come home and only sent her some cash. She took care of their son and lived with her mother-in-law. But after she got sick, she couldn’t even live this ordinary life anymore. She wasn’t even able to watch her child grow up.

When her son got married, she couldn’t even attend the wedding. It was only when she needed to return home to apply for government assistance that her daughter-in-law found out her husband actually had a mother. The daughter-in-law asked her why she hadn’t come back, and she said that even though she’d gotten treatment, she was still visibly affected by leprosy, and didn’t want people back home to know—it would prevent her son from having a normal life.

Now they see each other about once a year. They always meet in a shop in town. To this day, she has yet to return to her home village.

Some people had come with hopes that they could go home after being cured. At first, they thought they’d be able to go home after a few months or a year, but many people ended up staying for years. It’s not that the hospital won’t let them leave—in fact, the hospital encourages them to go home, but they can’t go back. Many have tried reintegrating into society, but society rejected them.

A former patient, called Uncle Biao, told me that he and his father both had leprosy. The two of them entered the hospital together when he was in his teens, and his father died there.

After Uncle Biao was cured and went to seek work, he faced discrimination wherever he went. He became a drifter, working odd jobs under the table. He only went back to the hospital when his foot rotted. At first, he wanted to return to his village, but the villagers came and got him at 4 a.m. and dropped him off outside the hospital.

The hospital director said it was alright to bring him in, but requested that the villagers help him get his ID so that he could get government assistance and health insurance.

The villagers agreed at once, saying that as long as they could leave him there, they’d help with anything.

My first time filming in this village was totally different from the second.

The first time, I left after just three or four days, and I had a pretty dim view of their lives. I felt that they were a tragic group of people. After getting back, I finished a cut of the film. The atmosphere was very dark, so when my classmates saw it, they all cried.

These days, I don’t like to go back and watch that film—it bothers me. To put it harshly, it’s just your typical tearjerker, playing to the audience’s sense of pity.

The second time was during the second year of my master’s degree, and I stayed for a longer period. It was only then that I really understood the villagers, knew what their lives were like.

Certainly, there were still hardships; but by this point in their lives, they had the range of emotions of any ordinary person, including joy.

Often, grief is still in their hearts, but they don’t show it, or they’ve learned to let it go and live in the moment.

Zhang Haonü, for example, is truly worthy of her name, “good woman.” From talking with her, I got the impression that she is very kind-hearted. When she talked about her husband and mother-in-law, she spoke without resentment, like she was telling someone else’s story. For the average person, if your husband had an affair or your daughter-in-law didn’t know of you, if your family concealed your existence, it would be hard to take.

But she is understanding of their choices, and calm when telling her story. She doesn’t hold it against them, or against the world.

Nowadays, she voluntarily does laundry for older residents in the village with limited mobility. I asked her why she does this. She said she simply wanted to help, because some of the older villagers had amputations, and had trouble taking care of themselves. She did this without expecting anything in return.

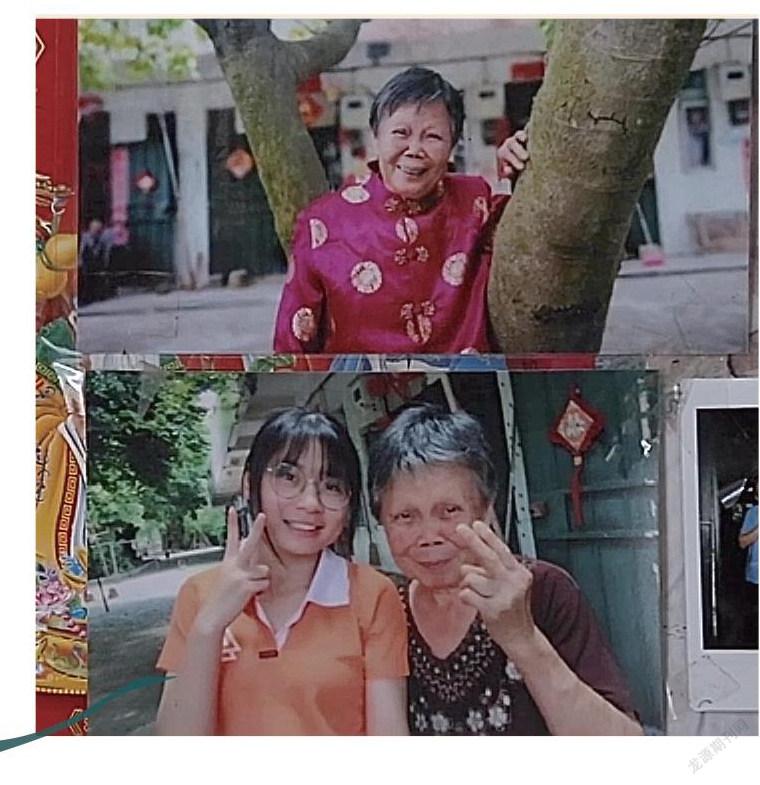

On the walls of her room, there were many group photos of volunteers who had come to the village. In some of the photos, she has cute gestures like making a heart shape with her fingers, or putting her fingers up by her ears.

When I took a picture with her, I hugged her tightly. I thought she was so good and kind, and I really felt for her.

The first time you see “Grandpa” Lin Zhiming, you might feel that he doesn’t quite fit in with the others. He has a scholarly character, and isn’t fond of small talk.

It was only after we’d been filming in the village for a long time that he asked us where we came from. We said we were from Beijing. Then he asked us to drop by his house for a visit if we had time. He spoke quite softly.

While chatting with him, my project partner wrote a few Chinese characters, and he said they were very well done—in Cantonese, very , free-flowing. He was full of praise for her. He must have been someone who really appreciates talent, so after he saw her calligraphy, we were able to get a little closer.

He’d contracted leprosy in his teens. He loved to read, but his school wouldn’t let him attend anymore after he got sick, so he borrowed some books to read at home.

He came to the leprosy village later in his teens. Because he had some education, he started teaching the other villagers. Everyone called him Teacher Lin. As his illness progressed, his fingers began to curl in on themselves, but he still continued teaching at the hospital.

After he was cured, he left the hospital to work in a cultural center. At first it went pretty well, because he was highly skilled and the director praised his work.

Later on, some other employees disclosed his illness to the director. After hearing rumors that he might infect others, the director told him that he should “have some self-awareness.” When Grandpa Lin got to this part of the story he got very angry, and started gesticulating. What the director meant was that he had to leave.

Grandpa Lin blew up in the office, shouting, “You are the ones who should have self-awareness! Before you heard those rumors, you couldn’t have treated me better! You patted my shoulder and told me good job. But as soon as you heard these rumors, you turn on me and force me out!” The director wouldn’t say that he was in the wrong, so Grandpa Lin walked out when he finished.

Later on, Grandpa Lin sold calligraphy on the streets to make a living. People in Guangdong typically hang couplets or scrolls of calligraphy for the Lunar New Year or for weddings. They would go to him to write them.

Because he was skilled, he made good money. He was happy when he made money, but he would feel sad again when it was time to eat. Especially around Lunar New Year, when he would wait until everyone finished eating dinner with their families before clearing his calligraphy table. After that, he would go to a barbecue stall and take some smoked sausages home to eat on his own.

It was during this period that the idea for writing a book started to germinate within him—a book about the life experiences of other leprosy patients he knew from the hospital.

He wrote the book while selling his calligraphy. It took eight or ten years to write. Every day, he would stand on the balcony or rooftop, writing down whatever came to mind. He wrote until he finished his book, .

He picked this title because he felt that it was as if this suffering truly did not exist in the human world, that the average person wouldn’t experience this kind of suffering. He hoped that after he finished this book, that kind of suffering would cease to exist on earth. This was one of his dreams.

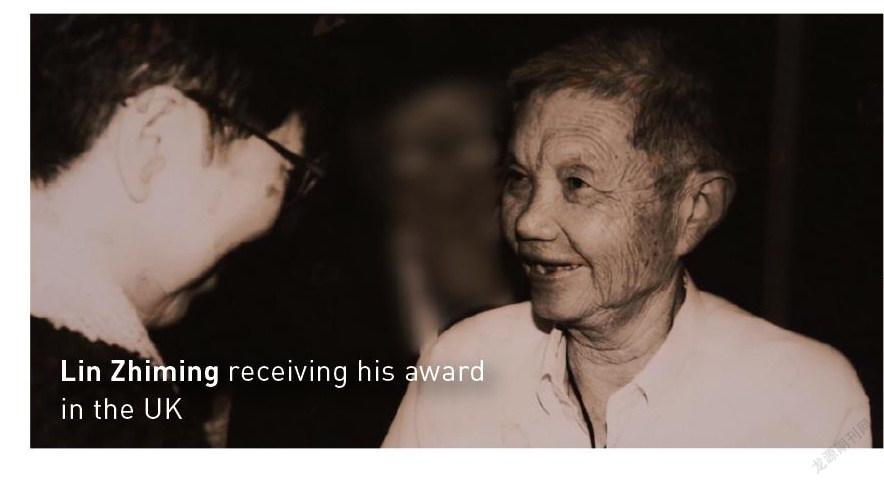

The book won an international award, and he went to the UK to accept it. He spoke mildly about his time there, but you could tell that within the calm there was some pride—that he felt this was a worthy accomplishment.

One day he said to me, “Little Chen, I still can’t stop worrying about my manuscripts. They are irreplaceable, and I hope to find a safe place to store them.” Then he asked me whether our group from Beijing might be able to help him.

I thought for a moment, and asked him where he wanted to put the book manuscript. He said libraries and similar places were all okay, and I asked him whether there was any library he particularly wanted. He said the Sun Yat-sen Library in Guangzhou was quite nice—it was either the largest or second-largest library in the city. So I decided to help him make the request.

After getting in touch with the library, I received a quick reply: They were able to accept the manuscript. With Grandpa Lin’s blessing, I went to his old home in Guangzhou and retrieved it.

The building was being rented out to migrant workers, and in poor condition. Once I got inside and closed the door, it was hard to make anything out in the darkness. I had to get to the attic by going upstairs and through another door. It was filthy inside. Everything was in disarray and covered in dust. There were several portraits of deceased family members, including Grandpa Lin’s mother. The place felt like a dusty relic. I don’t know why he would’ve left such important manuscripts there.

After searching for a long time, we finally found them—five books in all. My first impression upon opening them was that the handwriting really was beautiful. You could even make out distinct traces of his corrections, overlapping loops where he had written and rewritten.

We also came across some of his photos while we were searching. They were from when he went to the UK to accept his award: pictures of him posing with British people in front of well-known landmarks. It really was a glorious episode of his life.

For someone like him, being able to go abroad to receive this prize, to be recognized and praised—it must have been something he was very proud of.

We helped Grandpa Lin complete his quest in January or February of 2019. We initially didn’t think he would come to the library with us, but his friend’s daughter said it was best to have him come along, because his memory wasn’t great. If he didn’t make the trip himself, in a few days he might start thinking that the manuscripts still weren’t safe, then he’d start again asking everyday what should be done about them.

A funny memory from that trip was that the library staff spoke Cantonese, but he thought they only spoke Mandarin, so he started speaking in Mandarin himself.

I was on a trip to Inner Mongolia in summer 2019 when he called to ask how I was doing. He kept repeating how grateful he was that I’d helped him find a safe home for his manuscripts, fulfilling his greatest wish.

Hearing this, I suddenly felt warm. He actually remembered, even after all those months, and was still bringing it up. He said we should have a meal together if I went back, and so on.

Most leprosy patients never married. They lived their lives without experiencing marriage, having children, or starting a family.

Some of those who married other patients did so not out of love, but because they had similar experiences and tolerated one another.

They usually hoped to later have real, legal marriages.

There is an old gentleman called Kong Haobin. He and his wife met in the same hospital, and after being cured, they hoped to return home to start a family and live a normal life. With that very simple idea, the two of them packed their things and left. When they arrived in their hometown, they discovered that they were unable to register their marriage with the local government due to their medical history.

That was a very painful thing—Kong felt it would’ve been better not to come. So they went back to the hospital, but still had no way to live together. Because they couldn’t work much, any children would be a financial burden to them, so the hospital wouldn’t let them live together even if they were married.

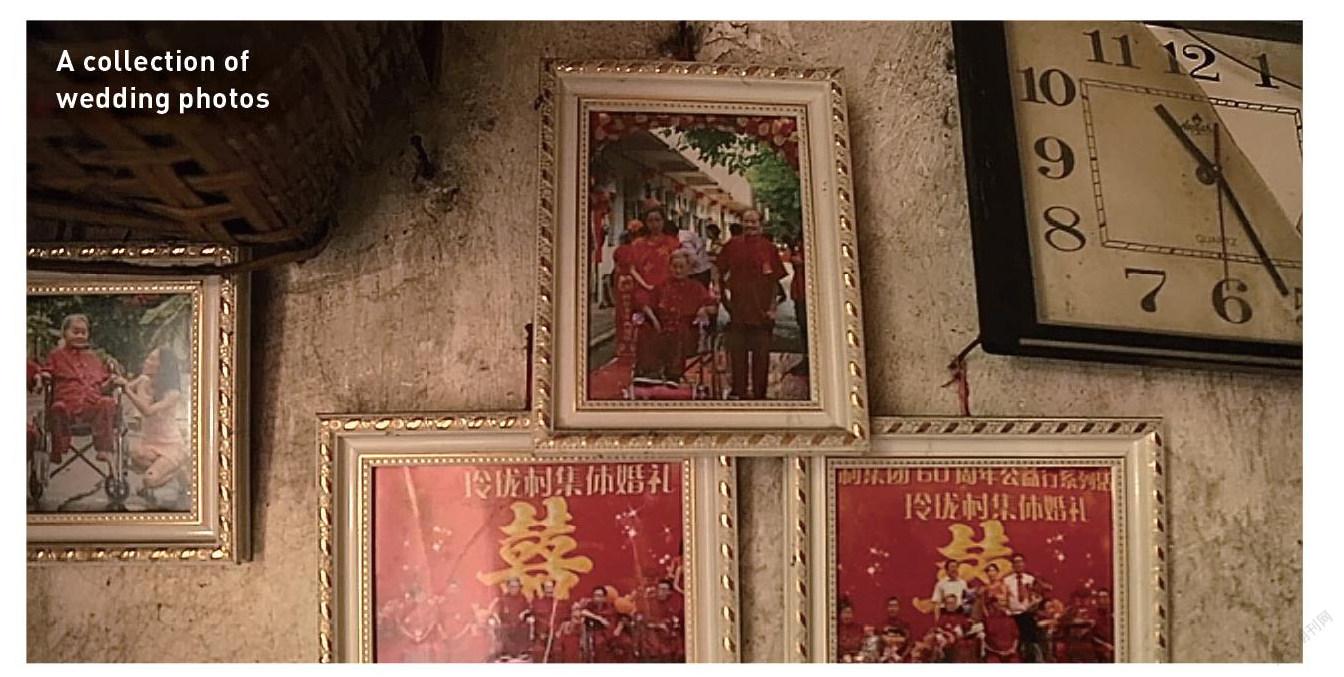

Kong felt that this was unfair: Why couldn’t marriage law ensure even this most basic right for a husband and wife to live together? He wrote out a petition and had other patients sign it, and then submitted it to the local authorities. A little over a month later, the official response came down. Later, they put on a mass wedding for over 60 people.

The day of the wedding, they set up several banquet tables. There were reporters and volunteers. After every couple came down the red carpet, they took a group photo and exchanged rings.

For many leprosy patients, it was inconceivable that they could someday marry like regular people. It was even less conceivable that so many people might come celebrate them. Even if they couldn’t put on the donated rings due to long-term finger damage, that ceremony was among the happiest, most unforgettable moments in their lives.

Kong Haobin is beginning to exhibit symptoms of dementia, and can’t think very clearly anymore. He fumbled with many of my questions, but had very clear recollections of that period of his life—even if you didn’t ask about it, he’d tell you.

It was only after the 80s, with the introduction of multidrug treatment, that leprosy became curable. By the 90s, the incidence rate was only 1 in 100,000—which is to say that we already had the capacity to eradicate this disease.

In the future, leprosy colonies will vanish for good. Maybe the last village will have just one elderly person remaining, and when that person dies, there will be no more residents. Then the colonies will truly recede into history, living on only in stories and videos.

I hope that those who didn’t know about this group of people will come to know them. I hope that people who stereotype them can come to see how they actually live.

In reality, they live much like any other group of elders. But it is only by understanding the suffering they’ve endured that we can really feel how precious their current zest for life is, and perceive their vitality.

I called this documentary . The name comes from a story by O. Henry that Grandpa Lin told us:

There once was a pair of students. They were inseparable, until one of them fell gravely ill. As she looked out the window from her sickbed at the leaves falling off a vine outside, she felt she would also leave the world when the last leaf fell. One night, there was a torrential squall. In order to save her friend, the other student braved the rain and climbed a ladder to draw a leaf on the vine. The next day, when the sick student saw that the leaf was still there, she felt that she could go on living, that she was going to be alright.

This was only a belief—her health hadn’t changed, but she now had the conviction to go on living. It was the same for the leprosy patients: Under those grueling conditions, the will to live was just like that leaf. Even if in some sense it wasn’t there, it was still something very important.

– Translated by Nathaniel J. Gan, Originally published by Story FM

Chen Yanü (right), director of the documentary The Last Leaf, at the leprosy village

A banner reads “Build a world without leprosy”

Lin Zhiming at home

Zhang Haonü washes clothes for the elderly in the village

Lin Zhiming receiving his award in the UK

A collection of wedding photos

Linglong Hospital (Leprosy Rehabilitation Village) was founded in 1958

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2022年1期

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2022年1期

- 汉语世界(The World of Chinese)的其它文章

- On the Character: 动

- No Excuses

- Rough Cut

- When China Goes on the Road

- A New Way of Seeing

- 学中文