An implementation study of barriers to universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention at tertiary hospitals in Thailand: Healthcare managers’ perspectives

Vitaya Titapant, Saifon Chawanpaiboon✉, Sanitra Anuwutnavin, Attapol Kanjanapongporn, Julaporn Pooliam,Pimolphan Tangwiwat

1Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700, Thailand

2Department of Social Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom 73170, Thailand

3Clinical Epidemiological Unit, Office for Research and Development, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700, Thailand

4Maternal and Child Health Division, Bureau of Health Promotion, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand

ABSTRACT

Objective: To identify healthcare managers’ perspectives on the barriers to implementing cervical length screening to prevent preterm births.

Methods: In PhaseⅠ, 10 healthcare managers were interviewed.Phase Ⅱ comprised questionnaire development and data validation.In Phase Ⅲ, the questionnaire was administered to 40 participants,and responses were analyzed.

Results: Their average related work experience was (21.0±7.2)years; 39 (97.5%) respondents also had healthcare management responsibilities at their respective hospitals. Most hospitals were reported to have enough obstetricians (31 cases, 77.5%) and to be able to accurately perform cervical length measurements (22 cases,55.0%). However, no funding was allocated to universal cervical length screening (39 cases, 97.5%). Most respondents believed that implementing universal screening, as per Ministry of Public Health policies, would prevent preterm births (28 cases, 70.0%). Moreover,they suggested that hospital fees for cervical length measurements should be waived (34 cases, 85.0%). Three main perceived barriers to universal screening at tertiary hospitals were identified. They were heavy obstetrician workloads (20 cases, 50.0%); inadequate numbers of medical personnel (24 cases, 60.0%); not believing that the screening test could prevent preterm birth (8 cases, 20%) and lack of free drug support for preterm birth prevention in high-risk cases (29 cases, 72.5%).

Conclusions: The main obstacles to universal cervical length screening are heavy staff workloads and inadequate government funding for ultrasound scanning and hormone therapy. The healthcare managers do not believe that the universal cervical length screening can help to reduce preterm birth.

KEYWORDS: Barriers; Healthcare managers’ perspective;Preterm birth prevention; Universal cervical length screening;Barriers; Tertiary hospital

Significance

Cervical length screening is one of the many strategies for preventing preterm births and is still not successfully implemented in Thailand. Our study identified the obstacles to performing this screening from the perspective of healthcare managers. The barriers to implementing a cervical length measurement programme are current heavy work tasks of physicians and a lack of government funding for ultrasound scanning and hormone therapy.

1. Introduction

A “preterm birth” is one that occurs before 37 weeks’ gestation[1].Pregnant women with preterm labour experience regular uterine contractions that may result in cervical progression and delivery of a stillborn or premature baby[2]. At least 10% of these women will deliver within 7 days of the onset of the contractions[2]. Preterm births are the most common cause of neonatal death, accounting for approximately 1.1 million premature deaths annually[3]. At the same time, the surviving infants are at high risk of developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adult life[4,5]. Therefore, a reduction in preterm births in Thailand will contribute to lowering the mortality rate of newborns younger than 28 days of life and reducing the number of low-birth-weight babies. A “low birth weight” has been defined by the World Health Organization as one that is below 2 500 g[2].

In Thailand, as elsewhere, the primary cause of a low birth weight is premature birth[6]. A UNICEF study[7] reported that in the year 2015, there were 132 million live births worldwide, with 15.5% of those being low-birth-weight babies. In developed, developing and underdeveloped countries, the low-birth-weight rate was found to be 7.0%, 16.5% and 18.6%, respectively. As to Asia, the rate was 18.3%, which was among the highest in the world. Southeast Asian countries had a low-birth-weight rate of 11.6%. In Thailand,newborns with a birth weight of < 2 500 g accounted for 9% of all live births in 2015[7]. The World Health Organization set a goal under its Global Nutrition Target to reduce the number of babies born with a low birth weight by 30%. In Thailand’s case, achieving the goal will mean that the rate for low-birth-weight babies, expressed as a percentage of live births, will fall from the current level of 9.0% to 6.3% by the year 2025[6].

In Thailand, there are an estimated 15 000 cases of preterm births annually[8]. Expenditure on preterm neonatal hospital care has been calculated to be in the order of 170 000 Baht/case(US $5 312/case), which equates to a total of 255 000 000 Baht/year (US $79 680 000/year). These figures exclude the longterm care costs incurred following hospital discharge[8].

Based on current evidence, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine[9], the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists[10], and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[11] have stated that cervical length screening between 20–24 weeks of gestation can help to identify women at risk of preterm delivery. The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics has also recommended that the screening should be performed for all pregnant women[12].

The pregnant women at risk of preterm delivery are those with a history of preterm birth or a cervical length of less than 1.5 cm.Progesterone administration has been reported to prevent preterm birth[13], and it was associated with a 34%–43% reduction in preterm births (relative risk 0.6; 95% confident interval 0.4–0.9)[14].

According to the 2017 Ministry of Public Health policies for preventing preterm births in Thailand[15], public health facilities are required to provide standardised and comprehensive maternal and child health services. This includes an efficient referral system for preterm birth prevention, a standardised quality of antenatal services, and screening for the risk of preterm delivery. According to the Ministry’s policies, pregnant women at risk of preterm delivery should receive measures in the form of cervical screening or other such methods. Moreover, the women at risk should be encouraged to utilize the preventive methods that are made available to them in the public healthcare system. Finally, the Ministry’s policies state that preterm babies should receive standardised care appropriate to the related delivery hospital’s potential[15].

The provision of universal cervical length screening is one of many Thai policies to prevent preterm births. It is recommended that screening should be performed at the gestational age of 20–24 weeks. As pregnant women with a short cervix (< 25 mm) have a high risk of preterm delivery, it is recommended that they should be treated with micronised progesterone vaginal suppositories to prevent preterm delivery[15]. However, it has been now around 4 years since those policies were introduced in Thailand. In the light of the present study’s assessment, it is considered that the policies were not successfully implemented. Most pregnant Thai women still do not receive cervical length screening.

Consequently, the objective of this research was to identify the obstacles to performing the screening from the perspective of healthcare managers in the field. Armed with that information,efforts could be made to improve the related management systems and resources, where needed, to provide comprehensive preventive support to pregnant women and reduce the incidence of preterm births.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample size

This was a prospective, descriptive, implementation study. This survey study utilised a questionnaire format. To ensure an adequately sized dataset, a proportion of the results of interest of 50% (P=0.5),an estimation error of ≤ 5% and a 95% confidence level (typeⅠerror= 0.05, 2-sided) were used. The number of healthcare managers needing to be surveyed was calculated to be 40.

2.2. Methods

The research was divided into three phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the sample size and questions screening.

2.2.1. PhaseⅠ: In-depth interviews

The information collected in the initial phase covered four aspects:1) general personal information; 2) context evaluation of the universal cervical length screening policy and the resources available to carry it out; 3) input evaluation of the benefits of performing cervical length measurements, the importance of universal screening,and the impact of executing universal screening; 4) process evaluation of a universal cervical length measurement programme and its barriers.

Exploratory interviews were conducted with 10 healthcare managers from various hospitals who had been recruited for the study. Prior to the interviews, those individuals had expressed a willingness to participate in the research project and had been invited to discuss it in a private counselling room. After the project details had been described, the healthcare managers were given time to ask questions and consider whether they wished to formally enrol in the trial. They were advised that they could decline to participate in the research or withdraw from it at any stage if they desired so. Those who decided to volunteer as a research subject were asked to sign an informed consent form before being formally interviewed at length.

The 10 participants were asked for permission for the conversations and the structured interviews to be audio recorded. The subjects initially completed a personal information questionnaire. Several topics were then examined in-depth in a structured interview.The topics related to the policy of implementing cervical length measurement for preterm birth prevention, the availability of resources, and any ideas relevant to the implementation of universal screening and its barriers. The time from the commencement of the filling in of the questionnaire until the interview close was about 30 min. The data integrity of the research questions was later verified.

2.2.2. PhaseⅡ: Development and validation of the questionnaire

The data obtained from the questionnaire and the 10 in-depth interviews were analysed to determine the means and standard deviations. This enabled the questionnaire and interview questions to be refined. The revised questionnaire and interview questions were tested for validity and reliability before their use in the next phase.The method for questionnaire reliability was test-retest reliability by giving the questionnaire to the same group of respondents at one month after revision. The questionnaire validity was checked by the statistician who was an expert on questionnaire construction and examined for double, confusing and leading questions.

2.2.3. Phase Ⅲ: Administration of the questionnaire

During the final study phase, the validated questionnaire was randomly given to 40 healthcare managers working in tertiary hospitals located throughout Thailand.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Demographic data were summarised using descriptive statistics,and categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages. All the statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

2.4. Ethics statement

Before its commencement, this study was approved by the Siriraj Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital(Si 343/2562). The Thai Clinical Trials Registry number was TCTR20190813003. All the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Si 480/2019)and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained.

3. Results

3.1. General personal information

The respondents’ personal information is detailed in Table 1. Their average age was (50.2±5.6) (range: 38–60) years. All had medical degrees, and they had graduated on average (26.4±5.7) (range: 14–36) years previously. They had worked in obstetrics and gynaecology for an average of (21.0±7.2) (range: 5–35) years. The respondents had also been in leadership or supervisory roles for an average of 3 years. All were directly involved in the provision of medical services,and 90% had teaching responsibilities. Most of the hospitals in the study had an inpatient capacity exceeding 500 beds.

Table 1. Personal information (can answer more than one choice).

3.2. Context evaluation of the universal cervical length screening policy and the resources available to carry it out

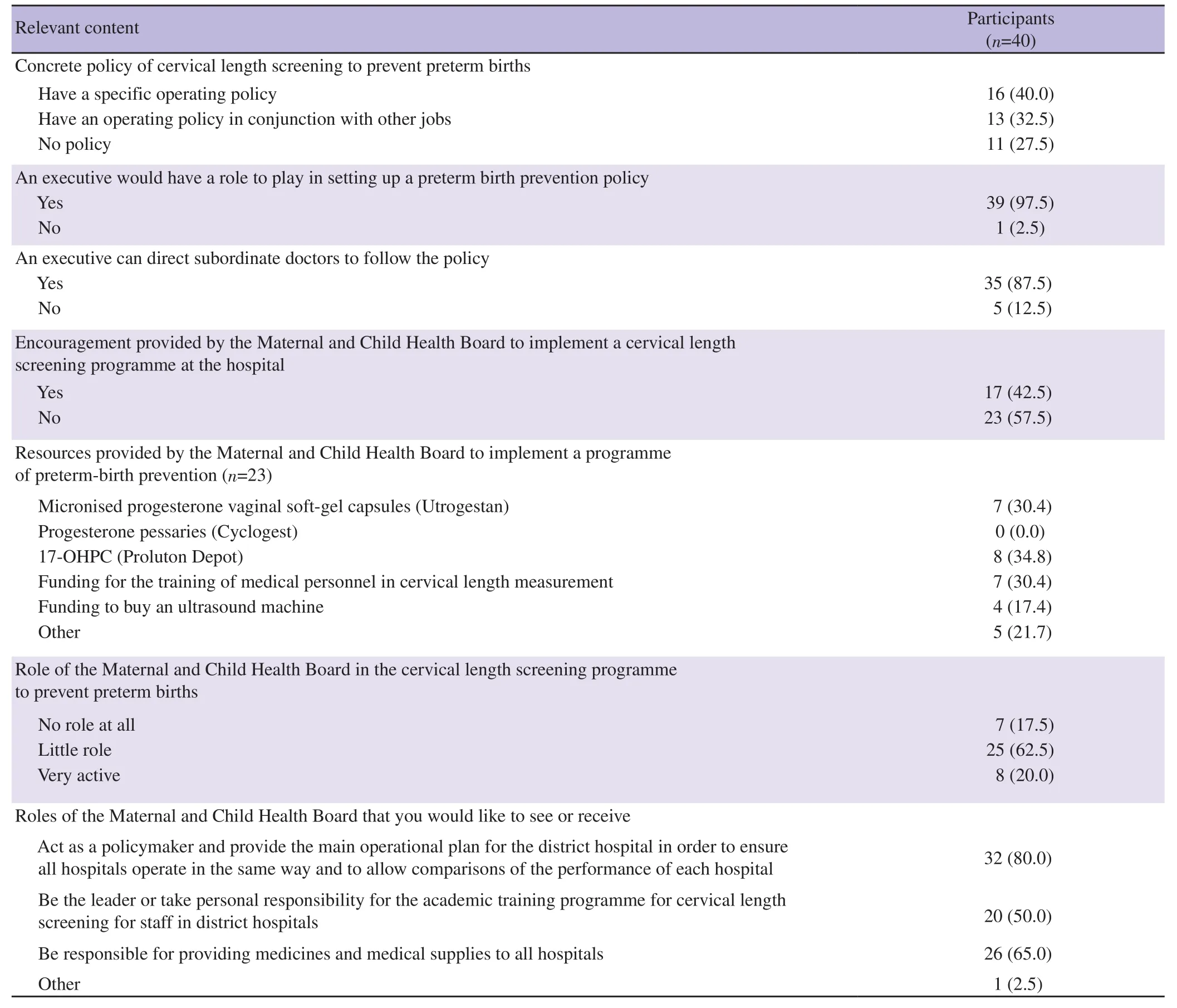

The context information on the tertiary hospitals included in the study is presented in Table 2. Forty percent of the tertiary hospitals had a policy of performing cervical length measurements to prevent preterm births. Almost all of the healthcare managers (39 cases,97.5%) were responsible for policymaking within their respective hospital settings. Most were of the opinion that the centrally located Maternal and Child Health Board (run by the Thai Ministry of Public Health) contributed by providing hormone support (namely,micronized progesterone vaginal soft-gel capsules) to preventing preterm births and supporting staff training for cervical length measurement (23 cases, 57.5%). However, the majority opined that the Board had little active involvement in premature birth prevention(25 cases, 62.5%). The key roles that hospital healthcare managers would like to see the Maternal and Child Health Board play are formulating national policies and providing district hospitals with the main operational plans to reduce the incidence of preterm births(32 cases, 80.0%).

Table 2. Context evaluation of tertiary hospitals (can answer more than one choice) [n (%)].

Table 3 summarises the availability of resources at the hospitals.Most hospitals were reported to have enough obstetricians (31 cases,77.5%). It was estimated that over 50% of the hospital obstetricians could accurately perform cervical length measurements (22 cases,55.0%) and were responsible for programmes promoting preterm birth prevention (32 cases, 80.0%). However, in most cases, there was no funding to run such a project (39 cases, 97.5%). Furthermore,the use of an ultrasound machine was considered sufficient for the project in many cases (20 cases, 50.0%).

Table 3. Availability of resources [n (%)].

3.3. Input evaluation of the benefits of performing cervical length measurements, the importance of universal screening,and the impact of executing universal screening

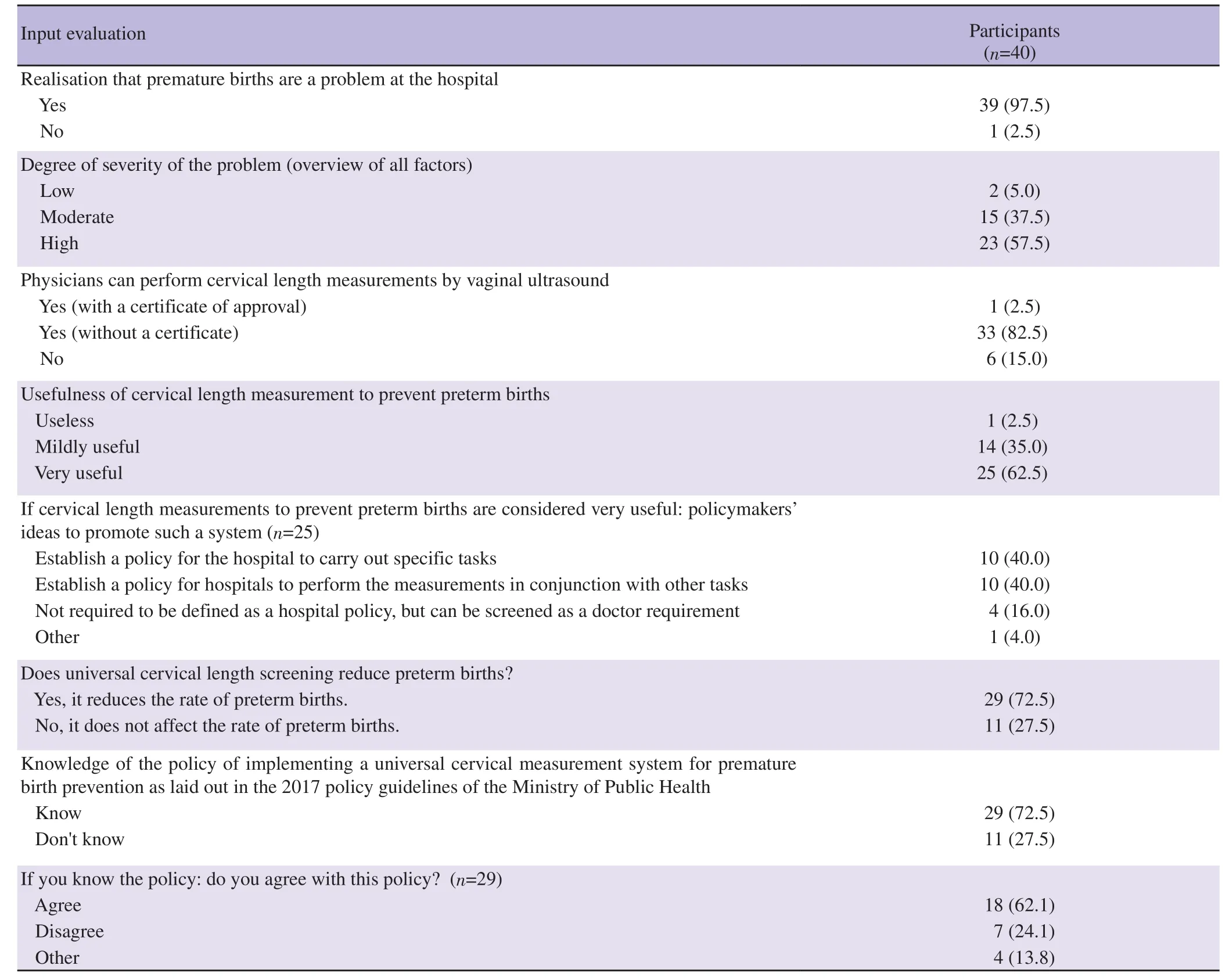

A tabulation of the assessments of the project inputs is given in Table 4. The healthcare managers recognised that preterm births are a major problem in almost all hospitals (39 cases, 97.5%) and a very serious problem in most cases (23 cases, 57.5%). While most hospital obstetricians were reported to be capable of performing vaginal ultrasound, they do not have certification approval (33 cases,82.5%). The healthcare managers considered that the ultrasound method is very useful (25 cases, 62.5%). A large minority opined that having a national, universal screening policy should prompt hospitals to carry out the related tasks either independently (10/25 cases, 40.0%) or in conjunction with other routine tasks (10/25 cases,40.0%). The healthcare managers also believed that the policy would reduce premature births (29 cases, 72.5%). In addition, the majority knew that a policy to perform universal cervical measurement for premature birth prevention was part of the 2017 policy guidelines of the Ministry of Public Health (29 cases, 72.5%), and most agreed with that policy (18/29 cases, 62.1%).

Table 4. Assessment of the project inputs [n (%)].

Table 5 lists the impacts of preterm births on pregnant women,family and on hospitals. Preterm births were reported to have a huge impact on the workloads of the relevant medical personnel (36 cases,90.0%). Moreover, the healthcare managers indicated that preterm births result in much greater hospital expenses than otherwise (34 cases, 85.0%) and the need for long-term hospital stays (37 cases,92.5%). In addition, the costs of caring for premature babies placed a high burden on most families (29 cases, 72.5%), as did the costs of treating the associated medical problems (37 cases, 92.5%). This financial burden was reported to greatly affect the lifestyle and work of the parents (35 cases, 87.5%). The healthcare managers also believed that the performance of universal screening in accordance with the Ministry of Public Health policy could prevent many preterm births (28 cases, 70.0%). As well, they suggested that the hospital fees for obtaining the measurements should be waived (34 cases, 85.0%). In many cases, despite a working group having been nominally organised within a hospital to drive the implementation of the preterm screening policy, there had been a lack of management follow-through (18 cases, 45.0%). Action plans to prevent preterm births were reported to be in force at most hospitals (33 cases,82.5%). These were supplemented by regular meetings to clarify related tasks (25/33 cases, 75.8%) and to review the provision of appropriate drugs and medical supplies (22/33 cases, 66.7%).

Table 5. Impact of preterm births on the pregnant women, family and the hospital [n (%)].

3.4. Process evaluation of a universal cervical length measurement programme and its barriers

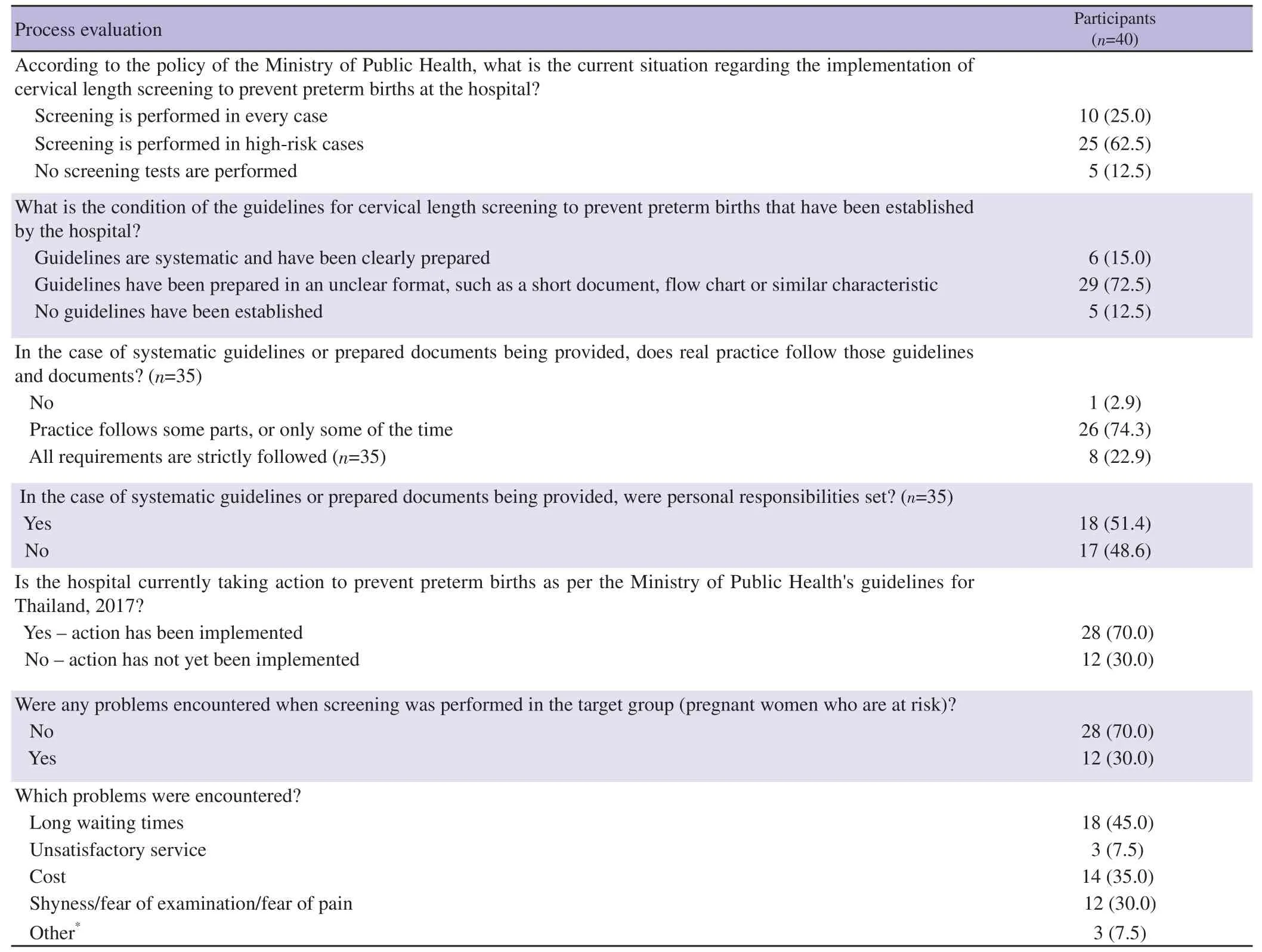

In line with the policies of the Ministry of Public Health for preterm birth prevention, cervical length screening was mostly performed only for high-risk groups (25 cases, 62.5%). However,the screening was typically conducted under an unclear system, with a lack of detailed guidance documents or process flow charts (29 cases, 72.5%). The screening was partly performed in some cases(26/35 cases, 74.3%), or as part of a clearly defined workload (18/35 cases, 51.4%). The policy guidelines for preterm birth prevention from the Ministry of Public Health, 2017, were observed by many of the tertiary hospitals (28 cases, 70.0%) and followed for high-risk groups (28 cases, 70.0%). However, certain service problems were apparent, such as long waiting times (18 cases, 45.0%) and high expense (14 cases, 35.0%) (Table 6).

Table 6. Process evaluation of the universal cervical length screening programme [n (%)].

The main barriers to implementing universal cervical length screening at tertiary hospitals were reported to be heavy obstetrician workloads (20 cases, 50.0%) and a lack of confidence in performing the measurements (20 cases, 50.0%). Other perceived barriers included an inadequate number of medical personnel (24 cases,60.0%) and the lack of free drug support for preterm birth prevention in high-risk cases (29 cases, 72.5%) (Table 7).

Possible ways to combat the identified barriers included: 1)reducing the unnecessary or unrelated workloads of physicians (18 cases, 45.0%); 2) providing physicians with training to increase their confidence in performing cervical length measurement (22 cases,55.0%); 3) providing adequate and regular funding from the relevant agencies (32 cases, 80.0%) (Table 7).

Table 7. Possible barriers to implementing universal cervical length screening in the hospitals, and possible ways to overcome the obstacles [n (%)].

4. Discussion

All of the administrative respondents in our study were obstetricians, so they had a good understanding of the problems related to preterm births. They all worked in the field of pregnancy screening services concomitant with performing other jobs, such as teaching and conducting research. Consequently, their workloads negatively impacted on their personal ability to participate in a universal cervical length screening programme.

However, the primary responsibility of healthcare managers at tertiary hospitals in Thailand is setting hospital policies and managing their subordinates to ensure their compliance with those policies. At the same time, the experience of the healthcare managers can influence the instructions they issue to subordinates regarding the need to observe established policies as well as their specific screening recommendations[16]. In particular, if the managers have personal experience with premature births, they are more likely to recommend screening[16]. Moreover, they are required to inform pregnant women about the risks of preterm delivery and its relationship with cervical length screening. Having more time available to describe the benefits of cervical length screening is necessary to properly assist patients to understand the importance of cervical length measurement[17]. Therefore, the healthcare managers’ workloads can affect the quality of screening as well as the educational processes within their hospital.

Performing cervical length measurements by vaginal ultrasound examination is useful and has been recommended to facilitate planning of patient management[18]. In terms of the accessibility and financial aspects of implementing cervical length measurement in Thailand, the Thai Ministry of Public Health has recognised the importance of cervical length screening to prevent premature births.The appropriate policies have been prescribed, and the necessary diagnostic tools are mostly sufficient. On the other hand, there are constraints related to the overall screening skill levels of the involved medical personnel at Thai public hospitals and the staff resources available there. Implementing universal cervical length screening to prevent preterm births is not just an issue for Thailand, but is a worldwide challenge.

From our study, almost all of the hospitals at the tertiary level (39/40 cases; 97.5%) still considered preterm births to be a major problem,and the respondents were well aware of the negative impacts of preterm deliveries. Most obstetricians in Thailand can perform cervical length measurements, even without certificate approval.However, 6 out of the 40 respondents (15%) stated they could not perform such measurements, and half (50%) were unsure of the correct method of performing cervical length measurements. Regular training programmes to improve and maintain skill levels should therefore be provided at tertiary centres.

The Thai public health system is committed to reducing preterm births. Many efforts have been made in this regard, including the establishment of a universal policy for cervical length measurement in Thailand to screen high-risk pregnant women for preterm delivery and to supply them with progesterone to prevent preterm births.Various forms of progesterone, including vaginal suppositories, oral medications and injections, have been prepared, but typically they are not free in Thailand. A previous study[19] that supported the use of natural progesterone in pregnancies stated that the administration of the hormone was not harmful to the nervous system; instead, it could actually prevent neurological complications. It has been reported that the use of 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, a synthetic progesterone, may have less benefit than natural progesterone[20]and may even have negative effects on the long-term functioning of a baby’s learning system[21]. Natural progesterone administered in a vaginal suppository form was found to reduce complications in newborns, with a reduced duration of hospital stay and reduction in preterm births, compared with 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate[21]. However, further long-term studies are needed.

Our research suggests that the Maternal and Child Health Board has little active role in the execution of screening programmes at Thai public hospitals. However, if programmes were fully established at each hospital with appropriate Maternal and Child Health Board oversight of their effectiveness, the willingness of subordinates to support universal screening could be improved.

The experience of obstetricians after examinations also affects cervical length screening. For example, pregnant women with a short cervix may have been found to have a higher rate of full term delivery than those with a normal cervix. Patients with a short cervix and who receive regular treatment may have a greater risk of preterm delivery. Recent data indicate that a cervical length screening programme followed by progesterone for those with a short cervix will reduce preterm birth rates by less than 0.5%[22]. The authors in that study believed that the screening did not actually reduce the preterm birth rate and that it may not have been worth using progesterone in the indicated pregnant women. Therefore, universal cervical length measurement has not been implemented in some hospitals in Thailand and remains controversial.

From our study, cervical length measurement was opposed by about 24.1% of all respondents. This supports the previous study’s finding that healthcare managers’ experiences influence their policy decisions on the implementation of screening at their hospital[16].Because of public healthcare funding constraints, some Thai hospitals do not have progesterone supplementation available for the treatment of patients with a short cervix. Hence, obstetricians at those centres may not be inclined to measure cervical lengths. Other reasons are heavy physician workloads, the length of time needed to perform the procedure and a reluctance of patients to undergo vaginal examinations. Patients may also find it inconvenient to use a vaginal drug and may prefer a weekly progesterone injection. Because of funding shortfalls, some tertiary hospitals in Thailand presently do not have both the vaginal and injected forms of progesterone available, which would make it impossible for them to provide progesterone prevention for pregnant women with a short cervix.

Cervical length measurement may not be available at all secondary hospitals. Therefore, relaxation or adjustment of the examination period should be considered to provide greater flexibility for cervical length measurement, so that more people living in rural areas can have the opportunity to undergo screening. A previous sensitivity analysis suggested that universal transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening is unlikely to be cost-effective when the prevalence of a transvaginal ultrasound cervical length of ≤20 mm falls below 0.31%[23]. Establishing the prevalence of short cervixes in a population and its contribution to preterm birth is therefore important before universal screening is introduced.

Multiple studies have shown that cervical length measurement and its implementation resulted in fewer preterm births and improved neonatal outcomes[19,24]. Cervical length measurements should be considered along with foetal anatomy screening during 19–20 weeks gestation. Abdominal ultrasound examination on a regular basis during the 18- to 20-week gestation period does not incur additional costs. Transabdominal ultrasound screening can reduce the need for transvaginal ultrasound and the subsequent costs[25]. Although up to 60% of pregnant women may still need transvaginal ultrasound[25],there is still the problem of who will bear the responsibility for the additional costs. However, some pregnant women clearly need serial screening for cervical length measurement. An additional costeffectiveness analysis would therefore be required and is a worthy parameter to assess.

The Maternal and Child Health Board should inform healthcare managers in the obstetrics and gynaecology units of Thai hospitals about any screening and treatment programmes. This action recognises the roles of those personnel in managing their subordinates and instructing pregnant women in the intricacies of the screening programme. Deficiencies in the knowledge of those healthcare managers in any area relevant to preterm births, defensive strategies, screening options, treatments and related interventions will reduce the prevalence of cervical length screening[26].Additionally, if a healthcare manager does not accept the value of screening or the performance of other preventive interventions, the likelihood that a patient will receive adequate counselling will also be hampered[27].

The research found that 62.5% of tertiary hospitals only screened high-risk women or those who had a previous preterm birth. This does not match the policies of the Ministry of Public Health. The main cause of preterm births was idiopathic in 60% of cases[28]; only 7% of preterm births involved mothers with previous deliveries[29].Therefore, universal cervical length screening is necessary,and adequate training of healthcare managers in obstetrics and gynaecology units should be pursued.

Nevertheless, our research found that most healthcare managers had a good level of awareness of the problem of preterm births and were willing to work to solve this serious problem in Thailand. The implementation of a universal cervical length screening programme accessible to all pregnant women should be possible.

The study has some limitations. Our study was conducted in only several tertiary hospitals in Thailand. The obstacles to performing cervical length screening identified in this study may differ from those found in the primary or secondary care centres which may have dissimilar conditions.

In conclusion, the main obstacles to implementing a cervical length measurement programme from the perspective of healthcare managers are the current heavy workloads of the staff who would be involved, unbelieving for the role of implemented policy to prevent preterm birth and a lack of funding for the costs of ultrasound scanning and hormone therapy. The elimination of unnecessary work tasks to reduce heavy physician workloads and the provision of adequate and regular funding by relevant government agencies would greatly facilitate the implementation of a universal cervical length measurement programme in Thailand.

Conflict of interest statement

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital,Mahidol University, Thailand (Grant No. [IO] R016233023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University for its funding support ([IO] R016233023). We also appreciate the administrative support provided by Nattacha Palawat.

Authors’ contributions

Vitaya Titapant and Saifon Chawanpaiboon contributed to the conception and design of the research; the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript; and the approval of the final manuscript. Sanitra Anuwutnavin contributed to revision of the manuscript and the approval of the final manuscript. Attapol Kanjanapongporn contributed to the transcription of data from the audio recordings and the approval of the final manuscript. Julaporn Pooliam contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and the approval of the final manuscript. Pimolphan Tangwiwat contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and the approval of the final manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2022年1期

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2022年1期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction的其它文章

- Successful live birth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection using testicular sperm in non-mosaic Klinefelter syndrome

- Effects of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in diluents on cryopreserved bull epididymal sperm

- Taurine in semen extender modulates post–thaw semen quality, sperm kinematics and oxidative stress status in mithun (Bos frontalis) spermatozoa

- Blepharis persica increases testosterone biosynthesis by modulating StAR and 3 β-HSD expression in rat testicular tissues

- Recurrent ovarian endometrioma after conservative surgery: A retrospective study

- Uptake of in-vitro fertilization among couples attending fertility clinic in a tertiary health institution