Early mobilization implementation for critical ill patients: A crosssectional multi-center survey about knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of critical care nurses

Hui Zhng , Huping Liu ,*, Zunzhu Li , Qi Li , Xioyn Chu , Xinyi Zhou ,Binglu Wng , Yiqin Lyu , Frnces Lin

a School of Nursing, Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

b Department of Critical Care Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China

c School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedicine, University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia

d Sunshine Coast Health Institute, Queensland, Australia

Keywords:Attitude Barriers Critical illness Early ambulation Intensive care units Knowledge Nurses Perception

ABSTRACT Objective: To explore critical care clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes and perceptions toward early mobilization of critically ill patients in ICUs.Design: A cross-sectional national survey was conducted.From January to August 2020, ICU nurses in 11 hospitals were surveyed by using a questionnaire on the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of ICU early mobilization.Results: Totally 512 nurses completed the questionnaire.The respondents’ mean score for knowledge of early mobilization was 6.89±2.91.The level of knowledge was good in 2.5%(13/512),fair in 52.3%(268/512).The attitudes toward early mobilization were positive in 31.4% (161/512).In terms of perceived implementation of ICU early mobilization,42.9%(220/512)of nurses did not believe that this should be a top priority in intensive care.The attitudes of nurses from different ICUs were significantly different(F = 3.58, P < 0.05).The knowledge (7.34 ± 2.78 vs.6.49 ± 2.97, t = 3.37, P < 0.001) and attitudes(3.82 ± 0.58 vs.3.52 ± 0.56, t = 5.63, P < 0.001) of nurses who had early mobilization related training were higher than those of nurses who had no training.Conclusions: The importance of early ICU early mobilization is increasingly recognized by critical care providers.However, there is still a gap in the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of ICU early mobilization among nurses.In future studies, it is necessary to further systematically identify the reasons leading to the gaps in these aspects and implement targeted interventions around these gaps.Meanwhile, more nurses should be encouraged to participate in decision-making to ensure the efficient and quality implementation of ICU early mobilization practices.

What is known?

· Early mobilization can be an effective intervention to reduce critical illness-associated muscle weakness in ICU patients;however, the uptake of early mobilization in ICUs remains low.

· Some studies have reported ICU clinicians’knowledge,attitudes,and perceptions on early mobilization of critically ill patients in developed countries,such as in Australia,the USA,and Canada,and the results varied.

· The most common perceived barriers to early mobilization in developed countries were medical instability, delirium, sedation, safety concerns, insufficient equipment and limited staffing.

What is new?

· Critical care nurses scored low on knowledge of early mobilization, and most of them held negative and neutral attitudes towards this intervention.

· Limited professional training availability was identified to have an impact on the critical care nurses’ level of knowledge and attitudes.

· Insufficient equipment and staffing levels, lack of related professional training and evaluation standards,concerns about the risks to patients and medical disputes, and healthcare professionals’awareness on early mobilization were highlighted as barriers by nurses.

1.Introduction

Advancement in contemporary intensive care medicine has decreased the mortality of patients with critical illness over the decades [1].Millions of people are discharged from ICU to general hospital wards, rehabilitation facilities, and homes each year [2].Prolonged bed rest, mobility restriction, mechanical ventilation,and sedation have been found to contribute to complications including depression, delirium, muscle weakness and major functional impairment [3,4].Current evidence shows that 38%-67% of critical ill patients experienced dysfunctions and impairments mentioned above[5,6],with 62%of the survivors having persistent symptoms for up to 10 years after ICU discharge, and only 37% of participants reported complete recovery from the symptoms [7].This consequently contributes to decreased quality of life and increased economic burden for the healthcare system, to the patients, and their families [8-10].

Studies have shown that early mobilization can be an effective intervention to reduce critical illness-associated muscle weakness in ICU patients [11-15].“Early mobilization” is the intervention targeted to prevent ICU acquired weakness of critically ill patients[16].“Early” means interval starting with initial physiologic mobilization and continuing through the ICU stay.This interval is early compared with interventions that usually begin after ICU discharge[16].Mobilization includes the activities that help critical patients to move,sit on the edge of the hospital bed without back support,sit in a chair after transfer from the hospital bed,and ambulate with or without assistance using a walker and/or support from ICU staff[16].

In a study conducted in ICUs of two university hospitals in the United States,the authors found that receiving mobilization in the earliest days of critical illness decreased the duration of mechanical ventilation by 2.7 days, shortened ICU delirium by two days, and improved functional independence during the 28-day follow-up period [11].The benefit of this strategy has been recognized by intensive care health professionals[17-19]and also recommended by some professional clinical practice guidelines [4,20].

Despite reported benefits, the uptake of early mobilization in ICU remains low [21], especially for mechanically ventilated patients [14,21,22].This low uptake is a global problem.In higherincome countries [23], about 24%-45% of patients received outof-bed activity in ICU [14,21,24,25].In a middle-income country[23], only 29% of patients received out-of-bed activity in ICU [26].Similarly, a survey conducted in China showed that only 19.15% of mechanically ventilated patients were mobilized out-of-bed [27].This shows a gap between research evidence and clinical practice.The reasons for this low uptake are multifactorial [28,29], and the situation varies in different countries, regions, and even ICUs within the same hospital [28].

The knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) Model [30]suggests that people’s practices (behaviors) are determined by people’s attitudes and knowledge.Therefore, healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices are considered to have a significant influence on the understanding and uptake of preventive measures (WHO, 2015).Positive attitudes and behavioral changes are driven by knowledge and perceptions towards preventive practices [31].The assessment of care providers’knowledge,attitudes and perceptions towards the implementation of early mobilization and its barriers has gained much interest from researchers from different countries.There have been some studies that reported clinicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions on the early mobilization of critical ill patients in developed countries.In Australia,Lin et al.reported that clinicians’knowledge score was 4.1±1.4 out of a possible score of 6 and early mobilization was not perceived as a top priority by 40.2%of participants[32].In the USA,Jolley et al.found that most clinicians are knowledgeable regarding the benefits of early mobilization,and showed universal agreement to the use of this intervention [22].In Canada, Koo et al.reported that clinicians had insufficient knowledge or skills to mobilize patients receiving mechanical ventilation,and many of them believed that early mobilization is crucial or very important in the care of critically ill patients [33].The most common perceived barriers to early mobilization were medical instability, delirium, sedation,safety concerns, insufficient equipment and limited staffing[22,32,33].To better understand this worldwide issue in clinical practice, more international evidence on health professionals’knowledge,attitudes and perceptions towards early mobilization in critically ill patients from other countries are required.

This study aimed to explore critical care nurses’ perceptions,knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers toward early mobilization.The following questions guided our study: 1) what are critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and perceptions toward early mobilization of critical ill patients in the Mainland of China?2) what are the differences in critical care nurses’ knowledge and attitudes according to their demographic characteristics? and 3)what are the perceived barriers associated with patients and nurses that influence the implementation of early mobilization?

2.Methods

2.1.Design

This is a cross-sectional,multi-center survey using a self-report online questionnaire.

2.2.Setting and participants

The participants were recruited from adult ICUs of 11 hospitals from China’s first-tier cities, which are also called “super cities,”where the population was more than ten million[34].The selected cities covered north, south, west and east of China using convenience sampling.Type of ICUs included respiratory,surgery,mixed,emergency, and medical ICUs.All participating ICUs are closed units, with the number of beds ranging from 10 to 39.

Nurses were eligible to participate if they: 1) were registered nurses who were employed full time to work in the participating ICUs during data collection;and 2)have worked at least six months in the ICUs before the study commencement.Exclusion criteria included 1) medical and nursing interns; 2) visiting and nurses undertaking training in these ICUs with a study duration of fewer than three months.According to the Kendll sample size method,the appropriate sample size is 5-10 times the number of questionnaire items [35].The number of questionnaire items in this study is 40,and 10 times the number of questionnaire items is used to calculate the sample size.Therefore,at least 400 respondents are required in this study.

2.3.Questionnaire construction

The survey was conducted in the Chinese language.A 32-item questionnaire developed by Lin et al.[32]used in a study conducted in Australia formed the basis of our survey instrument,and the procedure of the construction of the final questionnaire was based on Brislin’s classical back translation model [36].

2.3.1.Translation of the questionnaire from English to Chinese

Two postgraduate nursing students who were fluent in Chinese and English translated the questionnaire items from Lin et al.[32]from English to Chinese.We followed the following steps in the questionnaire translation: 1) translating the items from English to Chinese by the two students independently (Chinese version 1a and 1b); 2) synthesis of questionnaires: the research group held a group meeting to evaluate and discuss the differences between Chinese version 1a and 1b, and decided on one Chinese version of the questionnaire (Chinese version 2); 3) questionnaire review: a third team member who is fluent in Chinese and English conducted an independent review and comparison of the original English questionnaire and the translated Chinese version of the questionnaire to evaluate the equivalence of concepts,semantics and items.The sentences with a semantic consistency rate of less than 70%were retranslated until the semantic consistency reached more than 90%, and the Chinese version of the questionnaire was finalized.

2.3.2.Cultural adaptation of the questionnaire

The final version of the above-translated questionnaire in Chinese was revised based on the Chinese clinical and language context.To ensure the appropriateness of the terminologies used in the questionnaire, the correctness of understanding and acceptability,seven clinical experts with more than ten years of working experience reviewed the questionnaire.The review focused on the suitability of items of the questionnaire in the Chinese context,and the clarity of statements of the items.There was no change to the number of survey items at this stage.After reviewing, eight knowledge items [15,37,38], four attitude items [15,37,38]were added, two behaviors items were shifted to attitude items as they were more toward attitudes in the Chinese context (see Appendix A).Meanwhile, two attitude items were removed as we believed that the items were not suitable for the Chinese context.These included item number eight (overall, physiotherapy staffing is adequate to mobilize patients receiving mechanical ventilation)because there are no physiotherapists in Chinese ICUs,number ten(the risks to staff mobilizing mechanically ventilated ICU patients outweighs the benefits to the patients)because this is not the way to make a decision for Chinese nurses.

2.3.3.Thefinal Chinese version of the questionnaire

The final version of the questionnaire consisted of four parts with 40 items.Q1-Q12 assessed the demographic and professional characteristics of the participants.Q13-Q25 estimated healthcare providers’knowledge on early mobilization;each item had correct responses with a total score range from 0 to 13(1 point per correct answer for each item).The score of knowledge ranging from 8 to 10(60% correct) was regarded as “fair”, >10 (above 80% correct) was regarded as“good”.One score was awarded for each correct answer while “incorrect” or “not sure” answers took a zero score.Correct responses were summed up to get a total knowledge score for each participant.Q26-Q37 surveyed nurses’ attitudes toward early mobilization by using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5; 1(Strongly Disagree), 2 (Disagree), 3 (Uncertain), 4 (Agree), 5(Strongly Agree);the average score for attitudes ranged from 1 to 5 points.The attitude score was divided into three categories: positive (≥4), neutral (≥3, <4), and negative (<3).Q38-Q40 assessed the participants’ perception and perceived barriers of early mobilization (See Appendix A).

2.3.4.Questionnaire testing

The convenience sampling method was used to pre-survey 16 bedside clinical physicians and nurses who met the inclusion criteria in a tertiary hospital in Beijing.The aim was to ask the participants to review the suitability and clarity of the questionnaire items.The staff who completed the scale responded that all items of the scale were easy to understand and the questions were expressed clearly.The internal consistency of the questionnaire was 0.901, indicating that it had good reliability.

2.3.5.Data collection

The data was collected by using an online questionnaire on a Chinese online questionnaire platform called“Survey Star”(https://www.wjx.cn/).Before the survey, the first author explained the purpose of the study to the chief of the hospital nursing departments and the head nurses of the ICU in each hospital.The head nurses were asked to share the questionnaire link with their staff via the Chinese social media platform WeChat.Clicking on the shared link will open the questionnaire in the “Survey Star” platform.The front page of the e-questionnaire contained an information sheet for the survey and asked whether the candidates were willing to take part in the study.Only the nurses who chose‘agreed’ can proceed to the survey.Participants must answer all questions in the questionnaire to submit their responses.After each e-questionnaire was completed and submitted, the data were automatically saved on the secure platform.Each participant only had a single opportunity to answer the questions because of the set number of the limitations of the users’ IP addresses.

2.4.Data analysis

Data was exported into an excel spreadsheet from the e-questionnaire online platform.Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25.0(IBM Corp:Armonk,NY).Data are presented as frequencies, percentages, medians, and interquartile range (IQR).The differences of the pass and excellent rate of knowledge and attitude level of respondents according to the demographic and professional characteristics were conducted by using Chi-square analysis.Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to determine the association among the scores of the knowledge,attitudes and practice.

2.5.Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College.Participants were notified of the objectives of the survey, and the research involved no potentially harmful interventions.Participants completed the survey voluntarily.Their anonymity and confidentiality were assured.

3.Results

3.1.The demographic and professional characteristics of the respondents

Overall, a total of 512 questionnaires from nurses were submitted, which were all valid, with an effective rate of 100%.The number of ICU beds ranged from 10 to 39,among which,there were 10 units with 10-19 beds,16 units with 20-29 beds, and 6 units with 30-39 beds.

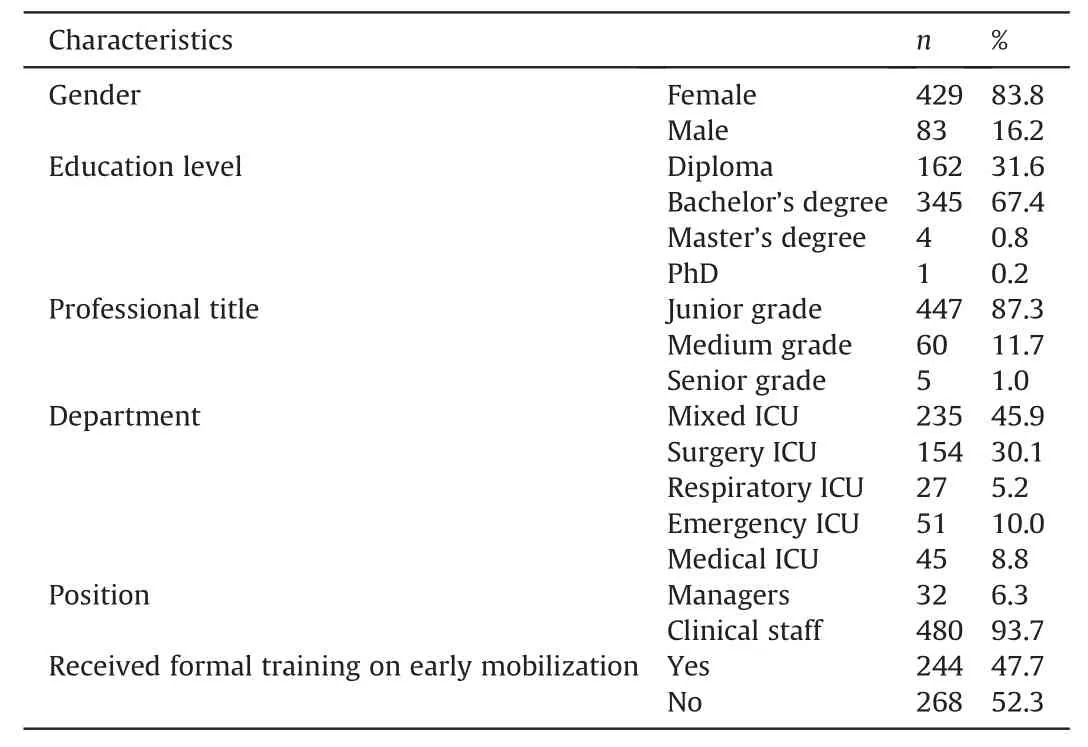

As the nonparametric test showed that the participants’ age,clinical experience,and ICU experience are abnormally distributed,we conducted median and inter quartile range (IQR) for these variables.The surveyed nurses’ median age was 29.00 (IQR:26.00-34.00), median years of clinical experience were 7.00 years(IQR: 4.00-12.00), median ICU experience was 6.00 years (IQR:3.00-10.00) (See Table 1).

3.2.ICU nurses’ knowledge on early mobilization

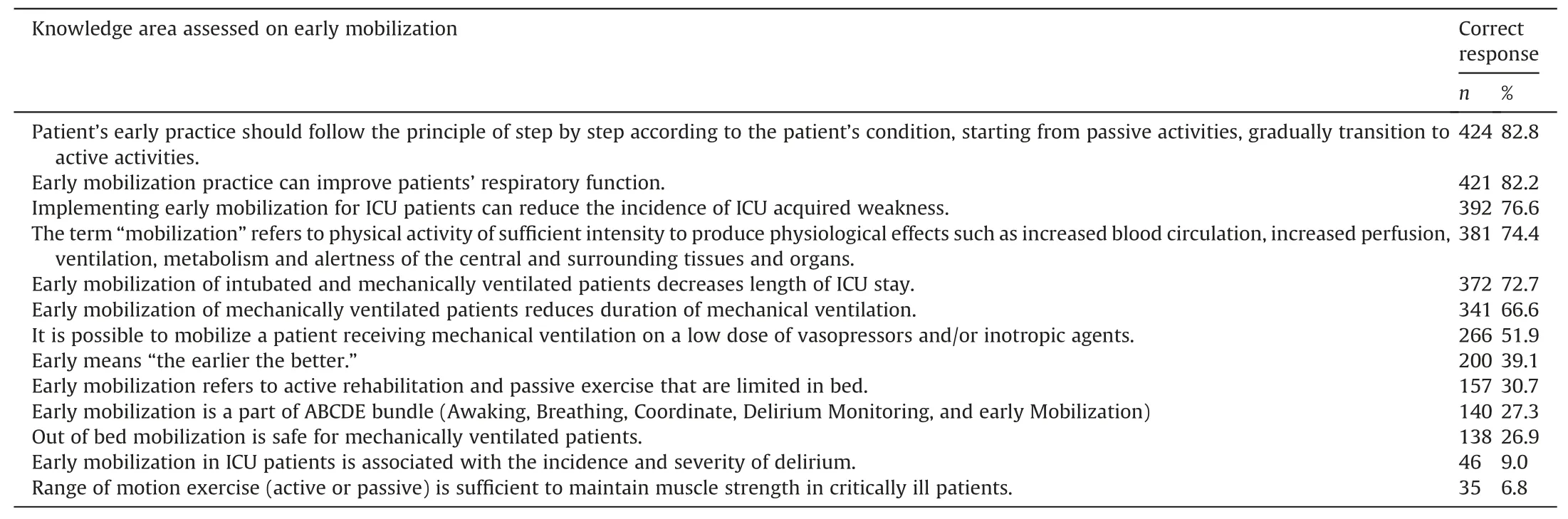

The respondents’ mean score for knowledge on early mobilization was 6.89 ± 2.91, which was significantly lower than the median point of overall score (8.00) (t= -8.59,P< 0.01).Only 54.9% (n= 281) participants achieved the passing score (≥8).In detail, statistical analysis indicated that nurses who had early mobilization-related training exhibited higher knowledge scores than those with no training (7.34 ± 2.78 & 6.49 ± 2.97,t= 3.37,P< 0.001).There is no statistically significant difference in ICU nurses’ knowledge scores with different education backgrounds,departments, clinical working experience, and professional titles.The accuracy rate of knowledge for each item is shown in Table 2.

3.3.The attitudes of ICU nurses towards early mobilization

Overall, most nurses showed neutral (n= 311, 60.7%) and negative (n= 40, 7.8%) attitudes toward early mobilization, and only a third of staff (n= 161, 31.4%) showed a positive attitude.

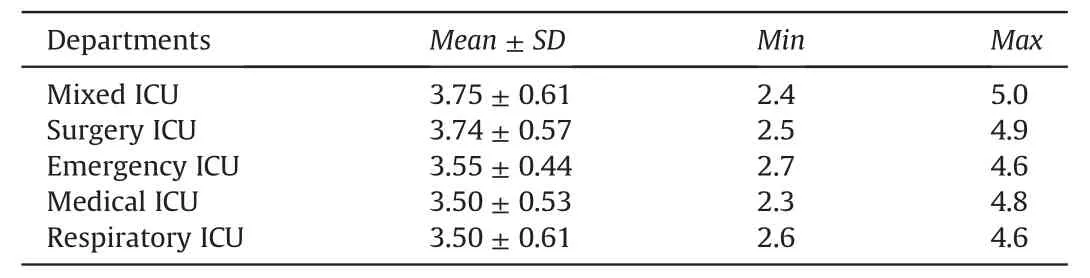

The average score of attitude was 3.66 ± 0.59.The score of attitudes of ICU nurses who had no training on early mobilization was lower than those who had training (3.52 ± 0.56 vs.3.82 ± 0.58,t= -5.63,P< 0.001).The attitude towards early mobilization of nurses who were working in different types of ICUs differed significantly (F= 3.58,P< 0.05).More details about the comparisons of nurses’ attitude scores toward early mobilization in different ICU departments are shown in Table 3.

3.4.Perceptions on early mobilization

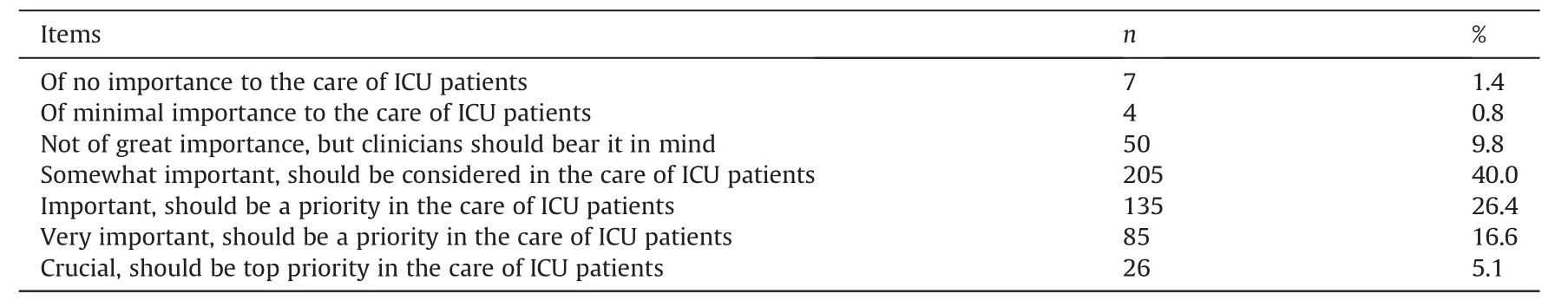

Less than 50% (n= 246, 48.1%) of the nurses thought early mobilization was important, very important, or crucial.Moreover,patients’ condition-related factors including instability of patients’condition(n=486,94.9%),mechanical ventilation(n=433,84.6%),and unconsciousness(n=424,82.8%)were highlighted as barriers.From nurses’ perspectives, insufficient equipment and staffing levels (n= 450, 87.9%), lack of appropriate professional training(n= 428, 83.6%), concerns about the risks to patients and medical disputes(n=410,80.1%),and awareness of healthcare workers for early mobilization (n= 409, 79.9%) were highlighted as barriers.More details are shown in Table 4.

Table 1Participants’ demographic data (n = 512).

Table 2ICU nurses’ knowledge related to early mobilization (ranked from high to low based on the accuracy rate, n = 512).

Table 3Comparison of nurses’ attitude among different ICU departments (n = 512).

4.Discussion

This study found that: (a) overall, many of the critical care nurses scored low on knowledge of early mobilization;(b)most ICU nurses held neutral or negative attitudes towards early mobilization, and less than half of the participants thought early mobilization was important, very important, or crucial; (c) training availability impacted on the nurses’ knowledge and attitudes of early mobilization; and (d) patients’ condition, nurses’ awareness of the implementation of early mobilization, and resource availability were perceived as barriers to early mobilization.

4.1.Nurses’ knowledge toward early mobilization needs to be improved

Our finding of nurses having insufficient knowledge to mobilize patients is supported by findings from studies conducted in Canada[33,39], Turkey [40], and Italy [41], but differs from other studies which reported that the level of knowledge of participants was high[15,32].The reason may be related to the differences in nurses’overall educational levels and the quality of training.In training programs for nurses,few were specified toward early mobilization.This result indicated that since early mobilization is recommended as routine care in the ICU context, the training on the practice of this intervention should be an important part of ICU nurses’training.

Our data suggest that nurses’ knowledge and attitudes to early mobilization differed depending on whether professional training was available.Professional training can enable ICU nurses to learn more knowledge related to early mobilization.However, in this study, 52.3% of nurses said they did not receive training related to early mobilization.This finding is concerning because early mobilization practices have been reported in the literature in the last decade.Hence, a strong awareness campaign is needed.

The accuracy rates of nurses’ understanding of the meaning,indication, and content of the early mobilization were found to be lower than 60% in knowledge items.The result is similar to the findings from previous research conducted in other countries[15,33,39,40].The results add to current literature calling for urgent attention on improving nurses’ knowledge on early mobilization and how to mobilize patients safely.Not having the necessary knowledge and not knowing the standard practices required for early mobilization might be a barrier to mobilize mechanically ventilated patients.It has been suggested that in-service training tailored to early mobilization,such as case-based teaching/sharing,simulation, and group discussion, can be effective[29].

4.2.Nurses’ attitudes towards early mobilization were suboptimal

More than 60% of respondents showed a positive attitude to early mobilization in previous studies [15,39].In contrast, only 31.4% of the participants in our study held a positive attitude towards early mobilization.This finding indicates that nurses’ attitudes towards early mobilization were suboptimal.Furthermore,ICU nurses’ attitudes towards early mobilization differed significantly among different types of ICUs.Nurses working in emergency ICUs, medical ICUs, and respiratory ICUs had lower attitude scores than nurses in mixed ICUs and surgical ICUs.This result may berelated to nurses’ different work intensity and the severity of patients’ conditions in the ICU [42]; however, it could also be influenced by contextual factors such as unit patient safety culture,resources, and staffing levels.Future research is needed to understand what contributed to these differences and identify the facilitators to early mobilization in the units where nurses had more positive attitudes than others.Lessons learned can inform future targeted interventions nationally and internationally.

4.3.The early mobilization has been perceived as a crucial intervention by ICU nurses while there are still many barriers to practice

The results in Table 4 showed that only 5.1% (n= 26) nurses thought the implementation of early mobilization was crucial and should consider this measure as the top priority in practice care,and 42.9%(n=220)nurses believed that early mobilization in ICU was important or very important.However, they did not think it was their top priority.This result is consistent with findings from studies conducted in Canada[33,39]and Australia[32].To address this barrier, specific protocols and targeted education on appropriate patient selection on a case-by-case basis may be needed [4,43].

Table 4Nurses’perceptions of the importance regarding early mobilization (n = 512).

Barriers to early mobilization in ICU have been extensively described in the literature [40,43-46].Consistent with previous studies, patients’ conditions, nurses’ awareness, and resources of the unit were perceived as barriers to early mobilization in ICUs.Among these barriers,insufficient resources are the most common obstacle [47].Unlike many countries around the world, in China,there are no respiratory therapists, occupational rehabilitation therapists and other professionals in the ICU of many hospitals[48].Moreover,as early mobilization is mainly performed by ICU nurses[48], the shortage of nurses further hinders the application of this intervention.Another barrier identified in our study was the lack of equipment to assist in mobilizing patients.In the surveyed ICUs,few of them have been equipped with devices to aid patient transfer, such as the use of electric hoists [48].Lack of equipment impeded nurses’ efforts to get patients out of bed.Hospital departments need to work collaboratively to address the issue by purchasing the necessary equipment to aid patient transfer,increasing ICU nursing staffing levels, employing physiotherapists,and encouraging medical staff members’ participation when mobilizing patients.

5.Limitations

A major limitation of this study is that the hospitals selected in this study were all from tertiary hospitals, from first-tier cities in China; thus, the findings may not be representative of early mobilization perceptions in ICUs in hospitals in other cities,limiting the generalization of the findings.However, the findings illustrated a deeper understanding of the issues related to early mobilization.

6.Conclusion

This study provided a deeper understanding of the perceptions,knowledge, attitudes and barriers of ICU nurses from hospitals covering different geographical areas in China.In this study, the results of ICU nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards mobilization are not optimal.Contributing factors are mainly related to insufficient education and awareness,unavailability of equipment,and low staffing levels.We suggest that in-service training related to early mobilization should be promoted in all ICU settings.Meanwhile, flexible nursing human resource management and integrating a mobility champion in ICUs could be effective ways to overcome the barriers to early mobilization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hui Zhang:Conceptualization,Methodology,Validation,Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft,Writing - review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.Huaping Liu:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation,Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.Zunzhu Li:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis,Investigation,Resources,Writing-review&editing.Qi Li:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis,Investigation,Resources,Writing-review&editing.Xiaoyan Chu:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis,Writing - review & editing.Xinyi Zhou:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.Binglu Wang:Conceptualization,Methodology,Validation,Formal analysis,Writing-review&editing.Yiqian Lyu:Conceptualization,Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition,Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.Frances Lin:Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft,Writing - review &editing, Project administration.

Funding

This project is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project number: 3332019171).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for their time and commitment to answer the questionnaire.

Appendices.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.10.001.

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2022年1期

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2022年1期

- International Journal of Nursing Sciences的其它文章

- The development of an evidence-informed Convergent Care Theory:Working together to achieve optimal health outcomes

- The development and implementation of a model to facilitate self-care of the professional nurses caring for critically ill patients

- Self-endangering: A qualitative study on psychological mechanisms underlying nurses’ burnout in long-term care

- Distress management in cancer patients:Guideline adaption based on CAN-IMPLEMENT

- Demand analysis of an intelligent medication administration system for older adults with chronic diseases based on the Kano model

- The decision for hospice care in patients with terminal illness in Shanghai: A mixed-method study